Edited by Margaret Gatz, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Renée Baillargeon November 20, 2020 (received for review May 23, 2020)

Author contributions: L.S.R.-R., A.C., and T.E.M. designed research; L.S.R.-R., A.C., A.A., M.d.B., H.H., S.H., D.I., R.K., A.R.K., T.R.M., S.P., R.P., S.R., E.S., A.T.S., J.W., A.R.H., and T.E.M. performed research; L.S.R.-R., T.d., M.E., R.M.H., A.R.K., L.J.H.R., and M.L.S. analyzed data; and L.S.R.-R., A.C., and T.E.M. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

We followed a population-representative cohort of children from birth to their mid-forties. As adults, children with better self-control aged more slowly in their bodies; showed fewer signs of brain aging; and were more equipped to manage later-life health, financial, and social demands. The effects of children’s self-control were separable from their socioeconomic origins and intelligence. Children changed in their rank order of self-control across age, suggesting the hypothesis that it is a malleable intervention target. Adults’ self-control was associated with their aging outcomes independently of their childhood self-control, indicating that midlife might offer another intervention window. Programs that are successful in increasing self-control might extend both the length (life span) and quality (health span) of life.

The ability to control one’s own emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in early life predicts a range of positive outcomes in later life, including longevity. Does it also predict how well people age? We studied the association between self-control and midlife aging in a population-representative cohort of children followed from birth to age 45 y, the Dunedin Study. We measured children’s self-control across their first decade of life using a multi-occasion/multi-informant strategy. We measured their pace of aging and aging preparedness in midlife using measures derived from biological and physiological assessments, structural brain-imaging scans, observer ratings, self-reports, informant reports, and administrative records. As adults, children with better self-control aged more slowly in their bodies and showed fewer signs of aging in their brains. By midlife, these children were also better equipped to manage a range of later-life health, financial, and social demands. Associations with children’s self-control could be separated from their social class origins and intelligence, indicating that self-control might be an active ingredient in healthy aging. Children also shifted naturally in their level of self-control across adult life, suggesting the possibility that self-control may be a malleable target for intervention. Furthermore, individuals’ self-control in adulthood was associated with their aging outcomes after accounting for their self-control in childhood, indicating that midlife might offer another window of opportunity to promote healthy aging.

The ability to control one’s own emotions, thoughts, and behaviors in early life sets the stage for many positive outcomes in later life. These include educational attainment, career success, healthy lifestyles (123–4), and, in particular, longevity (567–8). Prospective studies of children, adolescents, and adults have shown that individuals with better self-control—often measured as higher conscientiousness or lower impulsivity—live longer lives (567–8). But, do they also exhibit better midlife aging? Answering this question could reveal opportunities to extend not only life span (how long we live) but also health span [how long we live free of disease and disability (9)]. Here, we used data collected across five decades to connect children’s self-control to their pace of aging in midlife. We also linked children’s self-control with their midlife aging preparedness: the health, financial, and social reserves that may help prepare individuals for longer life span and better health span.

Midlife represents a useful window during which to measure individual differences in aging and their relation to childhood self-control. Meaningful variation between individuals in the speed of both physiological and cognitive aging can be detected already at this life stage (10, 11), and prior work has established that individual differences in midlife health are linked to early-life factors (1213–14). Furthermore, midlife is a critical period for preparing for the demands of older age (15). Now past their healthy young adult years, individuals must devote greater attention to preventing age-related diseases, increasing their financial reserves for retirement, and building the social networks that will provide practical and emotional supports in old age. Signs of one’s own aging emerge at this life stage, reminding us that multiple health, financial, and social demands are approaching: menopause and presbyopia set in, we start paying attention to our savings accounts, and we see our own futures in our parents’ decline.

If outcomes of self-control extend as far as midlife, then it could be a key intervention target. It would also suggest the hypothesis that there may be opportunities to build aging preparedness while individuals are still in their robust forties (15, 16). Much emphasis has been placed on the importance of intervening early in development, and there is vigorous debate over the optimal timing for implementing early-years programs (1718–19). Midlife, however, remains a largely unexplored potential window of opportunity for self-control intervention.

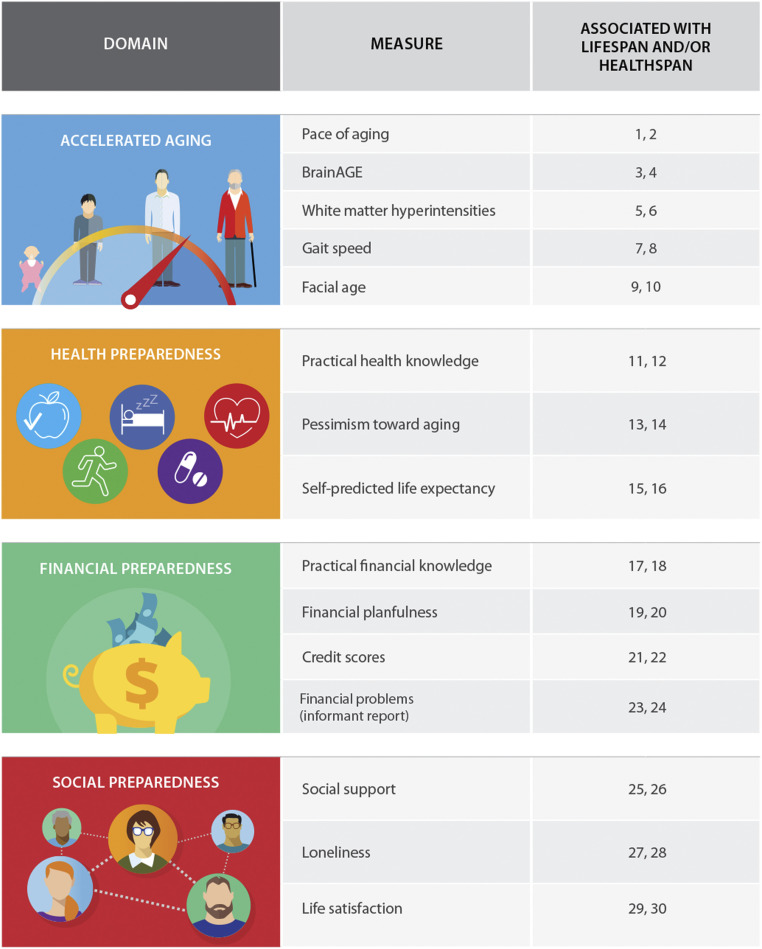

We tested associations between childhood self-control and midlife aging using data from the Dunedin Longitudinal Study, a prospective study of a complete birth cohort of 1,037 individuals followed from birth to age 45 with 94% retention. As previously reported in this journal, we measured study members’ self-control across their first decade of life using a multi-occasion/multi-informant strategy (2, 20). We measured their pace of aging as well as their aging preparedness in midlife using a range of prespecified measures known to be associated with life span and/or health span (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Table S1), which were derived from biological and physiological assessments, structural brain-imaging scans, observer ratings, self-reports, informant reports, and administrative records. We used these data to test two hypotheses. First, we tested the hypothesis that individuals with better self-control in childhood exhibit slower aging of the body and fewer signs of brain aging in midlife. Second, we tested the hypothesis that individuals with better self-control in childhood exhibit better preparedness for the health, financial, and social demands that emerge in later life. Research has shown that self-control predicts health behaviors such as diet, smoking, alcohol consumption, and exercise (4, 212223–24). Here, we extend the reach of this research by testing whether self-control predicts outcomes beyond health behaviors, including individuals’ practical health knowledge, their attitudes toward and expectancies about aging, their practical financial knowledge and financial behavior, their social integration, and their satisfaction with life.

Aging domains and measures assessed in the current study. Column three indicates reference numbers for prior studies documenting associations between the given measure and life span and/or health span. The complete reference list is included in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Children’s self-control is correlated with their socioeconomic circumstances (25, 26) and their intelligence (27, 28). Both social class and intelligence have been implicated in life span and health span (29, 30); in fact, both social class and intelligence have been called “fundamental causes” of later-life health (3132–33). Social class has been proposed as a fundamental cause because it influences multiple disease outcomes through multiple mechanisms, it embodies access to important resources, and its associations with health outcomes are maintained even when intervening mechanisms change (31). Intelligence has been conceptualized as a fundamental cause for similar reasons (32). For childhood self-control to be implicated as an active ingredient in healthy aging, it is important to show that its effects are independent of these two fundamental influences on children’s futures. We therefore tested whether associations between self-control and aging survived after accounting for children’s social class and intelligence quotient (IQ) [assessing each, like self-control, using repeated measurements across childhood (Methods)].

Results

Because all children lack self-control on occasion, we defined a child’s sustained self-control style using an omnibus measure of self-control that comprised reports collected at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11 y. These reports by researcher-observers, parents, teachers, and the children themselves assessed capacities including lack of control, impulsive aggression, hyperactivity, lack of persistence, inattention, and impulsivity (SI Appendix, SI Methods 1). They were combined into a highly reliable composite measure for each study child [α = 0.86 (2)]. Children with better self-control tended to come from more socioeconomically advantaged families (r = 0.27, P < 0.0001) and had higher tested IQs (r = 0.45, P < 0.0001).

Does Better Self-Control in Childhood Forecast Slower Aging of the Body and Fewer Signs of Brain Aging?

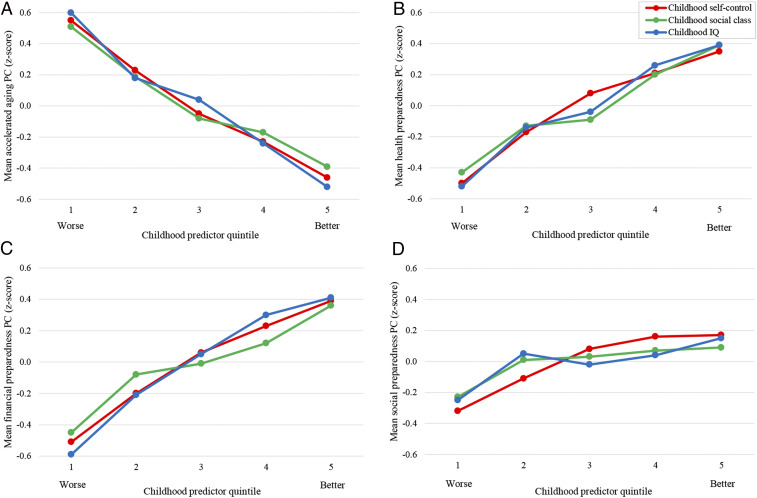

From ages 26 to 45 y, we measured the pace of study members’ physiological decline across multiple organ systems. At age 45 y, we also collected structural MRI measures to derive estimates of brain aging as well as the volume of white matter hyperintensities, a clinical index of microlesions that accrue across the life span and predict accelerated cognitive decline and dementia risk. In addition, we conducted assessments of study members’ functional capacity and asked several independent raters to judge each study member’s apparent age from facial photographs (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, SI Methods 2). These outcomes were correlated with each other (Table 1) and were therefore combined to form a composite measure of accelerated aging using principal components analysis. Children with better self-control displayed slower aging in later life, as assessed by this composite (β = −0.35, 95% CI [−0.42, −0.29], P < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 2). This remained the case even after controlling for their social class origins and IQ (β = −0.20 [−0.26, −0.13], P < 0.0001; Table 2). Self-control was also associated with each constituent measure individually. As adults, children with better self-control aged more slowly across different organ systems, had lower brain age scores, had a smaller volume of white matter hyperintensities, walked more quickly, and appeared younger in facial photographs shown to independent raters (Table 2). Associations with brain age and white matter hyperintensities became nonsignificant when we controlled for childhood social class and childhood IQ, but the remainder of associations were independent of these fundamental causes (Table 2).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | |

| 1. Childhood self-control | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Childhood IQ | 0.45 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Childhood social class | 0.27 | 0.41 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Accelerated aging PC | −0.34 | −0.40 | −0.31 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Pace of aging* | −0.29 | −0.29 | −0.24 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6. BrainAGE† | −0.12 | −0.17 | −0.11 | 0.48 | 0.20 | |||||||||||||||||

| 7. White matter hyperintensities (mm3)‡ | −0.10 | −0.09 | −0.10 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||||||

| 8. Gait speed (m/s) | 0.25 | 0.34 | 0.21 | −0.64 | −0.34 | −0.11 | −0.09 | |||||||||||||||

| 9. Facial age | −0.20 | −0.25 | −0.24 | 0.66 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.11 | −0.25 | ||||||||||||||

| 10. Health preparedness PC | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.28 | −0.44 | −0.37 | −0.14 | −0.15 | 0.29 | −0.32 | |||||||||||||

| 11. Practical health knowledge | 0.34 | 0.50 | 0.33 | −0.38 | −0.28 | −0.16 | −0.11 | 0.24 | −0.32 | 0.55 | ||||||||||||

| 12. Pessimism toward aging | −0.16 | −0.13 | −0.12 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.07 | 0.13 | −0.16 | 0.16 | −0.72 | −0.12 | |||||||||||

| 13. Self-predicted life expectancy | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.15 | −0.30 | −0.27 | −0.07 | −0.06 | 0.21 | −0.21 | 0.75 | 0.16 | −0.28 | ||||||||||

| 14. Financial preparedness PC | 0.31 | 0.37 | 0.26 | −0.45 | −0.40 | −0.20 | −0.08 | 0.25 | −0.34 | 0.40 | 0.35 | −0.28 | 0.21 | |||||||||

| 15. Practical financial knowledge | 0.39 | 0.60 | 0.36 | −0.44 | −0.37 | −0.19 | −0.08 | 0.29 | −0.31 | 0.38 | 0.53 | −0.17 | 0.15 | 0.66 | ||||||||

| 16. Financial planfulness | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.17 | −0.31 | −0.28 | −0.18 | −0.04 | 0.15 | −0.23 | 0.29 | 0.22 | −0.22 | 0.17 | 0.75 | 0.39 | |||||||

| 17. Credit scores | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.17 | −0.28 | −0.25 | −0.11 | −0.09 | 0.13 | −0.21 | 0.22 | 0.15 | −0.17 | 0.12 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 0.31 | ||||||

| 18. Informant-reported financial problems | −0.15 | −0.13 | −0.04 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.13 | 0.19 | −0.23 | −0.09 | 0.22 | −0.14 | −0.70 | −0.24 | −0.34 | −0.35 | |||||

| 19. Social preparedness PC | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.10 | −0.21 | −0.21 | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.13 | −0.14 | 0.48 | 0.12 | −0.54 | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.24 | −0.29 | ||||

| 20. Social support | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −0.16 | −0.16 | −0.03 | −0.04 | 0.11 | −0.09 | 0.36 | 0.10 | −0.37 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.17 | −0.19 | 0.80 | |||

| 21. Loneliness | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.06 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.10 | 0.10 | −0.35 | −0.08 | 0.41 | −0.17 | −0.24 | −0.13 | −0.20 | −0.15 | 0.21 | −0.82 | −0.48 | ||

| 22. Life satisfaction | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.10 | −0.22 | −0.22 | −0.08 | −0.05 | 0.11 | −0.15 | 0.48 | 0.12 | −0.54 | 0.27 | 0.37 | 0.18 | 0.29 | 0.27 | −0.30 | 0.83 | 0.49 | −0.54 |

Correlations were estimated controlling for sex. Estimates with absolute values of 0.09 or greater are statistically significant at P < 0.01 (with the exception of the relations between white matter hyperintensities and gait speed [P = 0.013] and between white matter hyperintensities and credit scores [P = 0.011]). Cells shaded in grey indicate correlations with our three predictors (childhood self-control, childhood IQ, and childhood social class). Cells shaded in blue, green, yellow, and red indicate correlations among the variables in the four aging domains. Bolded estimates in columns 1 to 3 indicate correlations between our three predictors and the principal components. Bolded estimates in columns 4 to 21 indicate the correlations among the variables within each aging domain. PC = first principal component. This table shows the correlations among the childhood predictors and aging outcomes of primary interest in the current study. Correlations with additional study variables (participant sex and adult self-control) are provided in SI Appendix, Table S4.

* Years of physiological change per chronological year.

† BrainAGE is the difference between participants’ predicted age from MRI data and their exact chronological age.

‡ Measure was natural log-transformed.

| Baseline associations | Adjusted for childhood social class and IQ* | |||

| Outcome | β (95% CI) | P value | β (95% CI) | P value |

| Accelerated aging | ||||

| Accelerated aging PC (z-score) | −0.35 (−0.42, −0.29) | <0.0001 | −0.20 (−0.26, −0.13) | <0.0001 |

| Pace of aging† | −0.30 (−0.36, −0.24) | <0.0001 | −0.20 (−0.26, −0.13) | <0.0001 |

| BrainAGE‡ | −0.13 (−0.20, −0.06) | <0.001 | −0.06 (−0.13, 0.02) | 0.134 |

| White matter hyperintensities (mm3)§ | −0.11 (−0.17, −0.04) | 0.003 | −0.07 (−0.15, 0.01) | 0.073 |

| Gait speed (m/s) | 0.26 (0.20, 0.33) | <0.0001 | 0.13 (0.06, 0.20) | <0.001 |

| Facial age | −0.21 (−0.28, −0.14) | <0.0001 | −0.10 (−0.18, −0.03) | 0.005 |

| Health preparedness | ||||

| Health preparedness PC (z-score) | 0.30 (0.24, 0.37) | <0.0001 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.25) | <0.0001 |

| Practical health knowledge | 0.34 (0.28, 0.41) | <0.0001 | 0.13 (0.07, 0.20) | <0.0001 |

| Pessimism toward aging | −0.16 (−0.23, −0.10) | <0.0001 | −0.12 (−0.20, −0.05) | 0.001 |

| Self-predicted life expectancy | 0.15 (0.09, 0.22) | <0.0001 | 0.11 (0.04, 0.19) | 0.003 |

| Financial preparedness | ||||

| Financial preparedness PC (z-score) | 0.32 (0.26, 0.39) | <0.0001 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.25) | <0.0001 |

| Practical financial knowledge | 0.40 (0.34, 0.46) | <0.0001 | 0.15 (0.09, 0.21) | <0.0001 |

| Financial planfulness | 0.21 (0.14, 0.27) | <0.0001 | 0.14 (0.06, 0.21) | <0.001 |

| Credit scores | 0.15 (0.09, 0.22) | <0.0001 | 0.11 (0.03, 0.18) | 0.005 |

| Informant-reported financial problems | −0.15 (−0.22, −0.09) | <0.0001 | −0.12 (−0.19, −0.04) | 0.002 |

| Social preparedness | ||||

| Social preparedness PC (z-score) | 0.18 (0.12, 0.25) | <0.0001 | 0.15 (0.08, 0.23) | <0.0001 |

| Social support | 0.16 (0.09, 0.23) | <0.0001 | 0.14 (0.07, 0.22) | <0.001 |

| Loneliness | −0.12 (−0.18, −0.05) | 0.001 | −0.09 (−0.17, −0.02) | 0.016 |

| Life satisfaction | 0.18 (0.11, 0.24) | <0.0001 | 0.14 (0.07, 0.21) | <0.001 |

All models combined men and women and controlled for sex. Supplementary analyses stratified by sex showed that self-control forecast aging outcomes in both men and women (SI Appendix, Table S5). β = standardized linear regression coefficient, CI = confidence interval, PC = first principal component.

* In secondary analyses suggested through peer review, we tested whether there were interactions between childhood self-control and childhood social class and between childhood self-control and childhood IQ in models predicting the four aging principal components. No interactions survived correction for multiple testing.

† Years of physiological change per chronological year.

‡ BrainAGE is the difference between participants’ predicted age from MRI data and their exact chronological age.

§ Measure was natural log-transformed.

Childhood predictors and midlife aging. Children with better self-control, who came from more socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds, and with higher IQs aged more slowly (A) and were more prepared to manage later-life health (B), financial (C), and social (D) demands. The means are adjusted for sex.

Does Better Self-Control in Childhood Forecast Better Preparedness for Later-Life Health Demands?

We also measured the degree to which study members were prepared to manage later-life health demands. At age 45 y, we conducted interviews with study members to measure their knowledge of practical health information; we used structured multiple-choice questions as well as open-ended questions such as “What are some of the reasons you should know your family history of illness?” and “If you are sick and the doctor gives you an antibiotic, what are some of the reasons why you should finish all the pills?” and coded their narrative answers later. We also administered standardized assessments to assess their attitudes toward aging and their self-predicted life expectancy (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, SI Methods 2). These outcomes were correlated with each other (Table 1) and were therefore combined to form a composite measure of health preparedness using principal components analysis. Study members with better self-control in childhood were more prepared in midlife to manage later-life health demands, as assessed by this composite (β = 0.30 [0.24, 0.37], P < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 2). This association persisted after controlling for childhood social class and IQ (β = 0.18 [0.11, 0.25], P < 0.0001; Table 2). Self-control was also associated with each constituent measure individually. As adults, children with better self-control had more practical health knowledge, held more optimistic opinions about the aging process, and were more confident that they would live to at least 75 y of age (Table 2). All associations were independent of childhood social class and IQ (Table 2).

Does Better Self-Control in Childhood Forecast Better Preparedness for Later-Life Financial Demands?

We investigated the degree to which study members were prepared to manage later-life financial demands. At age 45 y, we conducted interviews with study members, during which we assessed their knowledge of practical financial information; we used structured multiple-choice questions as well as open-ended questions, such as “How does the inflation rate affect the money you keep in a savings account?” and “Why do some people spread out investments and savings in different types of schemes?” and coded their narrative answers later. We interviewed them about their financial planfulness, including whether they owned their home or other property, had savings and investments, and had engaged in retirement planning. We also obtained, with informed consent, their official credit scores as well as informant reports of their financial behavior (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, SI Methods 2). These outcomes were correlated with each other (Table 1) and were therefore combined to form a composite measure of financial preparedness using principal components analysis. Study members with better self-control in childhood were more prepared in midlife to manage later-life financial demands, as assessed by this composite (β = 0.32 [0.26, 0.39], P < 0.0001; Table 2 and Fig. 2). This association remained evident after controlling for their social class origins and IQ (β = 0.18 [0.11, 0.25], P < 0.0001; Table 2). Self-control was also associated with each constituent measure individually. As adults, children with better self-control had more practical financial knowledge; were more financially planful; and had fewer financial problems, as indicated by better credit ratings (Table 2). These associations were verified by people whom study members had nominated as informants who knew them well. Participants with better self-control in childhood were rated by their informants as better money managers at age 45 y (Table 2). All associations were independent of childhood social class and IQ (Table 2).

Does Better Self-Control in Childhood Forecast Better Preparedness for Later-Life Social Demands?

Social life often diminishes after retirement as children move away and in older age if one’s spouse, friends, and other social contacts die. We investigated the degree to which study members had achieved the midlife social integration that would help prepare them to manage such later-life demands. At age 45 y, study members were administered standardized assessments of social support, feelings of loneliness, and satisfaction with life (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, SI Methods 2). These outcomes were correlated with each other (Table 1) and were therefore combined to form a composite measure of social preparedness using principal components analysis. Study members with better self-control in childhood were more prepared in midlife to manage later-life social demands, as assessed by this composite (β = 0.18 [0.12, 0.25], P < 0.0001; Table 2; Fig. 2). This was the case even after controlling for their social class origins and IQ (β = 0.15 [0.08, 0.23], P < 0.0001; Table 2). Self-control was also associated with each constituent measure individually. As adults, children with better self-control felt more socially supported, less lonely, and more satisfied with life (Table 2). All associations persisted after adjusting for childhood social class and IQ (Table 2).

Do Individuals Change in Their Self-Control across Age?

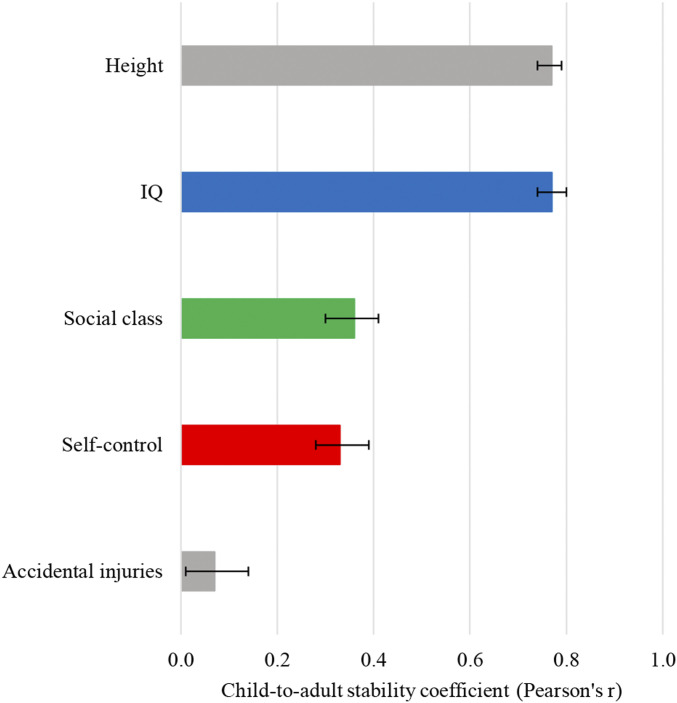

Children’s self-control forecast their pace of aging as well as their aging preparedness in adulthood. Is self-control a stable predictor of midlife outcomes, or do some children change in their self-control over time? We created a composite measure of study members’ self-control in adulthood using measures of self-control that were administered to multiple raters when the study members were 38 and 45 y of age, including close informants and Dunedin Study personnel [to parallel the multi-occasion, multi-informant strategy of our childhood self-control measure (Methods)]. Self-control in childhood was moderately correlated with self-control in midlife (r = 0.33, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3), indicating that some study members shifted in their rank in level of self-control across age. To contextualize this degree of child-to-adult stability, we calculated two benchmarks in our sample: height, for which individuals’ rank order is highly stable across age (r = 0.77, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3), and accidental injuries, which are, by definition, highly unstable (r = 0.07, P = 0.03; Fig. 3). The degree of child-to-adult stability in self-control fell in between these two benchmarks. This was also the case for children’s social class (r = 0.36, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). By contrast, IQ was as stable across age as height (r = 0.77, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3). Although our findings are observational, the natural history change in self-control that we observed suggests that self-control might also be subject to intervention-induced change. Furthermore, whereas children’s IQ may be highly difficult to change, there is the possibility that their self-control may offer a more malleable target. A caveat is that our adult measure of self-control was not identical to our childhood measure. However, both measures had good reliability and validity and it is unlikely that measurement factors alone can explain the lower stability in this estimate relative to IQ. Supporting the potential benefits of self-control change, individuals who became more self-controlled from childhood to midlife also aged slower and had better aging preparedness at age 45 y (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Some individuals became less self-controlled across age; they aged faster and had poorer aging preparedness (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

Child-to-adult stability in self-control, social class, and IQ. The figure shows that some Dunedin Study members shifted naturally in their self-control from childhood to adulthood. The degree of stability in self-control was similar to that for social class and substantially lower than that for IQ. Also shown are benchmarks for low (accidental injuries) and high (height) developmental stability, computed within this analytic sample. Child and adult accidental injuries were measured as annual accidental injury rates from birth to age 11 y and from 38 to 45 y, respectively. Child and adult height in millimeters were measured as a composite (standardized within sex) from ages 5 to 11 y and at age 45 y, respectively. Correlations are adjusted for sex. The bars are 95% CIs.

Given that individuals change in their self-control across age, midlife might represent another period during which to build aging preparedness. However, are both adult and childhood self-control important for midlife aging, independent of each other? Participants’ self-control in adulthood was associated with their pace of aging and their health, financial, and social preparedness, even after accounting for their self-control in childhood (βs [absolute values] = 0.33 to 0.54, Ps < 0.0001; SI Appendix, Table S2). Participants’ self-control in childhood also predicted their pace of aging, health preparedness, and financial preparedness after accounting for their self-control in adulthood (βs [absolute values] = 0.14 to 0.22, Ps < 0.0001). It did not independently predict their social preparedness (β = 0.06, P = 0.091; SI Appendix, Table S2), suggesting that associations between childhood self-control and midlife social integration are largely accounted for by individuals’ contemporaneous behavior.

Discussion

Higher self-control is known to forecast longevity (567–8). Our findings suggest that youth with better self-control do not just live longer, but also age more slowly as adults and are better prepared by midlife to manage the aging process. In this five decade prospective study of a population-representative birth cohort, children who exercised better control over their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors later experienced less age-related decline in their bodies, showed fewer signs of brain aging, were more attentive to practical health and financial information, were more consistent in implementing positive health and financial behaviors, exhibited more positive attitudes toward and expectancies about aging, were more socially integrated, and were more satisfied with life. For nearly all associations, the effects of children’s self-control could be disentangled from their socioeconomic origins and intelligence, suggesting the possibility that self-control itself might be an active ingredient in healthy aging.

Our analysis is strengthened by four design features. First, the Dunedin Study has a high retention rate (94%), reducing the potential for attrition bias [and the small amount of study attrition was not related to childhood self-control (SI Appendix, SI Methods 3)]. Second, we employed a rigorous measurement strategy for children’s self-control (reports from multiple informants across multiple occasions), social class (standardized assessments across multiple occasions), and intelligence (full-scale IQ assessments across multiple occasions). Third, we assessed participants’ aging at a period when individuals are still relatively healthy, at midlife, increasing the potential for our findings to inform preventive interventions. Fourth, associations with self-control were present across a range of aging outcomes assessed using different methods.

We acknowledge limitations. First, our data were right-censored at midlife. We therefore could not confirm that cohort members with better health, financial, and social preparedness at midlife will also exhibit better aging in later life [although the indicators of preparedness that we selected have been previously implicated in life span and/or health span (Fig. 1 and SI Appendix, Table S1)]. We also could not test whether building aging preparedness during midlife impacts longevity. Second, our findings are limited to a cohort of individuals born in New Zealand in the 1970s who are primarily white. However, associations between self-control and longevity have been observed across samples from different countries, born at different times, and of different ethnicities (567–8) (although importantly, these samples are from Western countries, and more research is needed in non-Western populations). Third, we utilized an omnibus measure of self-control rather than focusing on specific self-control capacities. Intelligence comprises different verbal, visuoperceptual, working memory, and processing speed abilities, and social class summarizes income, education, and occupational prestige. Similarly, researchers have argued that self-control comprises multiple abilities with diverse neural underpinnings, and different disciplines conceptualize and measure self-control in different ways using different methods [e.g., as conscientiousness, impulsivity, effortful control, ego strength, willpower, self-discipline, self-regulation, delay of gratification, executive function, and temporal discounting (34353637383940–41)]. Future research should aim to determine whether different self-control abilities and concepts relate to aging outcomes. Fourth, our measure of adult self-control was based on brief personality scales rather than comprehensive inventories (but it was strengthened by the use of reports from multiple raters across multiple occasions). Fifth, although our measure of physiological aging was based on longitudinal data, our measure of brain age was derived from imaging data collected at one time point. Prospective imaging data are needed to measure within-subject changes in brain age. Sixth, our observational study can only identify better childhood self-control as an indicator of better adult aging, not necessarily an indicator of causation.

With these limitations in mind, several implications can be noted. First, our results suggest the hypothesis that raising self-control in childhood could promote both life span and health span. Although our observational analysis did not incorporate an intervention component, we found that participants shifted in their rank order of self-control across age (and that participants who became more self-controlled also had better outcomes), suggesting that self-control might be subject to change and a malleable target for intervention. This conclusion is bolstered by data supporting the effectiveness of self-control– and self-regulation–focused interventions (42434445–46) [although some studies have obtained smaller effect sizes or found that the magnitude of effects varies depending on intervention type and design features (46, 47)].

Second, our findings have implications for self-control measurement and theory. Renewed debate over the importance of early-life self-control has emerged from efforts to replicate associations between children’s delay of gratification [as measured by the marshmallow test (48)] and their academic and behavioral outcomes, with researchers reporting smaller associations when employing more representative samples and after controlling for social class and cognitive ability (49). With respect to measurement, this raises the question of whether alternative approaches to assessing self-control (like the multi-occasion/multi-informant approach we used) might yield stronger associations with life outcomes than a single behavioral task. Laboratory tasks provide important information about self-control processes, but findings are mixed concerning how well they predict behavior in the real world (3, 5051–52). Measuring multiple self-control behaviors to ascertain a child’s style of self-control across situations, reporters, and years may capture the broader range of capacities that comprise this umbrella construct and that are important for real-world outcomes. Our multi-occasion/multi-informant approach to assessing children’s self-control yielded robust associations with aging outcomes measured over three decades later.

With respect to theory, results from our study and others (49) raise the question of whether self-control should be conceptualized as a construct that is distinct from socioeconomic origins and intelligence. It is unclear whether these latter constructs should be viewed as “confounds” to be partialled out of self-control associations or, rather, whether they represent important contributing factors to aspects of self-control (53). Self-control measures have been found to predict success in certain life domains as well as or better than measures of socioeconomic origins (2, 54) and intelligence (2, 27, 5455–56), and some early-childhood programs that improve self-control show positive effects on academic, occupational, and health outcomes even without improving intelligence (or socioeconomic status) (17, 57). Self-control continued to predict nearly all aging outcomes in our study after accounting for socioeconomic origins and intelligence, which is rather remarkable given the degree to which it was correlated with these factors (rs = 0.27 and 0.45, Ps < 0.0001; Table 1). (Exceptions were associations with MRI measures of brain age and white matter hyperintensities, which were attenuated to nonsignificance after controls for childhood socioeconomic status and IQ. This suggests that associations between self-control and neurological aging may be largely explained by socioeconomic origins and intelligence, or it might reflect that effects of self-control on neurological aging—as conferred via an accumulation of environmental factors—are not yet apparent in midlife.) Taken together with meta-analytic data supporting the prospective value of self-control for life success (3), our findings raise an additional question for self-control theory: whether self-control should be considered a “fundamental cause” of children’s later-life outcomes alongside their socioeconomic origins and intelligence (3132–33).

Third, our findings suggest the hypothesis that midlife might be a propitious time at which to revisit the opportunity to promote healthy aging (15, 16). Much work has focused on the importance of intervening in childhood and adolescence, but comparably little attention has been paid to the potential benefits of intervening later in the life course. We found that Dunedin Study members differed in their pace of aging as well as their health, financial, and social preparedness at midlife, indicating that meaningful variation in aging can be detected already at this period. Moreover, individuals’ self-control in midlife was associated with their pace of aging and aging preparedness even after accounting for their self-control in childhood, suggesting that building self-control in midlife—while adults are still relatively healthy—might confer unique benefits for life span and health span. We measured participants’ aging when they were in their mid-forties, but age-related diseases do not typically onset until the sixties in developed nations (58, 59), indicating a 15- to 20-y window for intervention. There is evidence to support the potential utility of intervening at midlife. Smokers who quit in midlife live longer (60, 61), and individuals who build better cardiovascular fitness in midlife live longer and are less likely to develop dementia (62, 63). There is also evidence that positive midlife practices [e.g., use of adaptive coping strategies to manage life stressors (64)] can interrupt the association between childhood adversities and negative long-term health outcomes (15). Furthermore, the population tends to improve in self-control across age (65), and even individuals who were at the low end of the self-control distribution as children may thus be better positioned as adults to implement the practices necessary to stem age-related decline. A key area for future research is to develop, test, and measure the returns on midlife interventions to enhance aging preparedness. Such approaches could range from individual-level therapies [e.g., cognitive-behavioral and transdiagnostic approaches for emotion regulation (44)] to organizational nudge tactics [e.g., opt-out retirement savings plans (66, 67)]. Programs already developed to assist adults in preparing for age-related demands in one domain might be expanded to adopt a “whole-person approach”; for instance, retirement planning programs could incorporate health and social planning in addition to financial planning. Failing to capitalize on these potential opportunities for intervention could have implications not only for individual well-being, but also for economic and health policy. Premature retirement places a burden on pension financing (68), and age-related diseases are incurring growing healthcare costs (69).

Lastly, our findings identify both opportunities and challenges for future aging research. With respect to opportunities, an open question is how childhood self-control impacts individuals’ psychological readiness for old age. Here, we have shown that children with better self-control reach midlife better prepared to handle the demands of later life. Do these individuals also feel subjectively more equipped to navigate the aging process? Our participants who had better self-control as children expressed more positive views of aging and felt more satisfied with life. Answering this question in greater depth could inform our understanding of the cognitive and emotional mechanisms that connect early self-control skills to midlife aging preparedness. A second open question is the potential magnitude of returns on investment in self-control interventions (e.g., number of healthy life-years gained). This can only be ascertained with prospective data that extend into old age. A key challenge for such work will be how to retain participants with the poorest self-control for follow-up. Nonresponse to national surveys has been growing [although the problem is worse for cross-sectional than longitudinal surveys (70)]. In order to obtain unbiased estimates of the returns on self-control interventions, researchers will need to attend carefully to the design and implementation strategies necessary to retain their least conscientious and most rapidly aging participants.

Societal changes have amplified the role of self-control in preparing for later-life health, financial, and social demands: more healthcare providers emphasize patient choice, more jobs are sedentary, more high-fat fast foods are available, more online advertising tempts poor money management, more individuals manage their own retirement savings, and more adults live alone. These changes present new opportunities for prevention and intervention scientists. If the associations documented here are causal, programs that increase self-control might improve not just length of life, but also quality of life: the ability to progress through old age in good health, with financial security, and with strong social bonds.

Methods

Dunedin Study Sample.

Participants were members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study, a longitudinal investigation of health and behavior in a complete birth cohort. Dunedin participants (n = 1,037, 91% of eligible births, 52% male) were all individuals born between April 1972 and March 1973 in Dunedin, New Zealand, who were eligible based on residence in the province at age 3 y and who participated in the first assessment at age 3 y. Details are reported elsewhere (71). The cohort represented the full range of socioeconomic status in the general population of New Zealand's South Island. On adult health, the cohort matches the New Zealand National Health and Nutrition Survey on key health indicators (e.g., body mass index, smoking, and visits to the doctor) and matches the New Zealand Census of people the same age on educational attainment (72).

Assessments were performed at birth; at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32, and 38 y; and, most recently, at age 45 y, when 938 of the 997 participants (94.1%) still alive participated. Participants who took part at age 45 y did not differ significantly from other living participants in terms of childhood self-control, childhood social class, or childhood IQ (SI Appendix, SI Methods 3).

At each assessment, participants are brought to the research unit for interviews and examinations. These data are supplemented by searches of official records and by questionnaires that are mailed, as developmentally appropriate, to parents, teachers, and peers nominated by the participants themselves. Written informed consent was obtained from participants, and study protocols were approved by the New Zealand Health and Disability Ethics Committee.

Childhood Self-Control, Social Class, and IQ.

Childhood self-control.

Children’s self-control during their first decade of life was measured using a multi-occasion/multi-informant strategy. This article reports a composite measure of overall self-control that we have described in previous publications (2, 20). Briefly, the nine measures of childhood self-control in the composite include observational ratings of children’s lack of control; parent and teacher reports of impulsive aggression; and parent, teacher, and self-reports of hyperactivity, lack of persistence, inattention, and impulsivity. At ages 3 and 5 y, each study child participated in a testing session involving cognitive and motor tasks. The children were tested by examiners who had no knowledge of their behavioral history. Following the testing, each examiner rated the child’s lack of control in the testing session (73). At ages 5, 7, 9, and 11 y, parents and teachers completed the Rutter Child Scale [RCS (74)], which included items indexing impulsive aggression and hyperactivity. At ages 9 and 11 y, the RCS was supplemented with additional questions about the children’s lack of persistence, inattention, and impulsivity (75). At age 11 y, children were interviewed by a psychiatrist and reported about their symptoms of hyperactivity, inattention, and impulsivity (76) (SI Appendix, SI Methods 1).

The nine measures of self-control in childhood were all similarly positively and significantly correlated. Based on principal components analysis, the standardized components were averaged into a single composite score (M = 0, SD = 1) with excellent internal reliability [α = 0.86 (2)]; the first component in a principal components analysis accounted for 51% of the variance.

Childhood social class.

The socioeconomic statuses of cohort members’ families were measured using a six-point scale that assessed parents’ occupational statuses, defined based on average income and educational levels derived from the New Zealand Census (77). Parents’ occupational statuses were assessed when participants were born and again at subsequent assessments up to age 15 y. The highest occupational status of either parent was averaged across the childhood assessments (78). Children’s social class scores (M = 3.75, SD = 1.14) were normally distributed (skewness = 0.22).

Childhood IQ.

The Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised (79) was administered to the study members at ages 7, 9, and 11 y. IQ scores for the three ages were averaged and standardized (M = 100, SD = 15). Children’s IQ scores were normally distributed (skewness = −0.61).

A more detailed description of each aging outcome reported below is included in SI Appendix, SI Methods 2.

Accelerated Aging Outcomes.

Pace of aging.

Pace of aging was measured for each study member with repeated assessments of a panel of 19 biomarkers taken at ages 26, 32, 38, and 45 y, a method previously described (10). The 19 biomarkers were as follows: body mass index, waist–hip ratio, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1C), leptin, blood pressure (mean arterial pressure), cardiorespiratory fitness (VO2Max), forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), forced vital capacity ratio (FEV1/FVC), total cholesterol, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, apolipoprotein B100/A1 ratio, lipoprotein(a), creatinine clearance, urea nitrogen, C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, gum health, and caries-affected tooth surfaces. We modeled change over time in each biomarker with mixed-effects growth models and composited results (scaled by sex) within each individual to calculate their pace of aging as years of physiological change occurring per one chronological year. Pace of aging (as captured through a DNA-methylation algorithm) predicts mortality (80).

Brain Age Gap Estimate (BrainAGE).

At age 45 y, participants completed a neuroimaging protocol to detect structural age-related features of the brain. Images (T1-weighted structural and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery) were acquired using a 3-T magnetic resonance imaging scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra; Siemens Healthcare GmbH) equipped with a 64-channel head and neck coil. High-resolution structural images were used to generate estimates of brainAGE: the difference between an individual’s predicted age from MRI data and their exact chronological age, between birth and the date of the MRI scan. We generated brainAGE scores using a recently published, publicly available algorithm (11, 81). This method uses a stacked algorithm to predict chronological age from multiple measures of brain structure (cortical thickness, cortical surface area, and subcortical and global brain volumes) derived from Freesurfer v5.3. The intraclass correlation (ICC) of brainAGE in 20 study members who repeated the MRI protocol an average of 79 d apart was 0.81 (95% CI = 0.59 to 0.92; P < 0.001). Analyses used brainAGE scores as an estimate of brain age.

White matter hyperintensities.

To identify and extract the total volume of white matter hyperintensities (WMHs), T1-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images for each participant were processed with the UBO Detector, a cluster-based, fully automated pipeline with high reliability in our data (test–retest ICC = 0.87 [95% CI = 0.73 to 0.95; P < 0.001]) and out of sample performance (82). The resulting WMH probability maps were thresholded at 0.7, the suggested standard. WMH volume is measured in Montreal Neurological Institute space, removing the influence of differences in brain volume and intracranial volume on WMH volume. WMH maps for each participant were manually checked by two independent raters to ensure that false detections did not substantially contribute to estimates of WMH volume. Visual inspections were done blind to the participants’ cognitive status. Due to the tendency of automated algorithms to mislabel regions surrounding the septum as WMHs, these regions were manually masked out to further ensure the most accurate grading possible. Participants were excluded if they had missing FLAIR scans, multiple sclerosis, or inaccurate white matter labeling or low-quality MRI data, yielding 852 datasets (841 for our analyses, as we required that participants have data on all childhood predictors to be included). WMH volume was log-transformed for analyses.

Gait speed.

At age 45, gait speed (meters per second) was assessed with the six-meter-long GAITRite Electronic Walkway (CIR Systems, Inc.). Gait speed was assessed under three walking conditions: usual gait speed (walk at normal pace from a standing start, measured as a mean of two walks) and two challenge paradigms, dual task gait speed (walk at normal pace while reciting alternate letters of the alphabet out loud, starting with the letter “A,” measured as a mean of two walks) and maximum gait speed (walk as fast as safely possible, measured as a mean of three walks). We calculated the mean of the three walk conditions to generate our composite measure of gait speed (83).

Facial age.

Study members’ facial age was evaluated on the basis of ratings by an independent panel of eight raters of standardized photographs of each participant’s face made during their assessment at age 45 y, a method previously described (11). Facial age was based on two measurements: age range, in which raters used a Likert scale to categorize each participant into a five-year age range (from 20 to 24 y old up to 70+ y old) (interrater reliability = 0.77), and relative age, in which raters used a Likert scale to assign a “relative age” to each participant (1 = “young looking” and 7 = “old looking”) (interrater reliability = 0.79). The facial age measure was derived by standardizing and averaging age range and relative age scores. The facial age measure was correlated with self-reports, informant impressions, and Dunedin Study unit staff impressions of study members’ age appearance (rs = 0.36 to 0.63).

Health Preparedness Outcomes.

Practical health knowledge.

Study members' practical health knowledge at age 45 y was indexed by two scales:

Multiple-choice assessment.

Participants were administered a multiple-choice assessment of their understanding of different health principles, including those related to medical knowledge, prevention, aging, physical disease, sun exposure, and sleep (range = 0 to 6, α = 0.41).

Open-ended interview.

Participants were interviewed about their understanding of different health principles with an open-ended response format (e.g., “What are some of the reasons you should know your family history of illness?”; “If you are sick and the doctor gives you an antibiotic, what are some of the reasons why you should finish all the pills?”). Using standardized scoring procedures, four trained raters (two per interview) coded the responses on a scale from 0 to 2 (0 = no understanding of the health principle, 1 = moderate understanding, and 2 = good understanding [interrater reliability = 0.94]). Scores were summed across items and then averaged across raters (range = 1 to 12).

The practical health knowledge measure was computed by standardizing and averaging the multiple-choice and open-ended scales.

Pessimism toward aging.

Study members’ pessimism toward aging was assessed at age 45 y using the Attitudes Toward Own Aging subscale of the Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale (e.g., “Things keep getting worse as I get older”) (84, 85).

Self-predicted life expectancy.

At age 45 y, study members were asked, “How likely is it that you will live to be 75 or more?” (0 = not likely, 1 = somewhat likely, and 2 = very likely) (86).

Financial Preparedness Outcomes.

Practical financial knowledge.

Study members’ practical financial knowledge at age 45 y was indexed by two scales:

Multiple-choice assessment.

Participants were administered a multiple-choice assessment of their understanding of different financial principles, including items adapted from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development/International Network on Financial Education Toolkit (87). Principles included those related to mortgages/loans, inflation, interest, and risk and return (range = 0 to 6, α = 0.64).

Open-ended interview.

Participants were interviewed about their understanding of different financial principles with an open-ended response format (e.g., “What is the advantage of paying off your credit card balance each month?”; “Why do some people spread out investments and savings in different types of schemes?”). Using standardized scoring procedures, four trained raters (two per interview) coded the responses on a scale from 0 to 2 (0 = no understanding of the financial principle, 1 = moderate understanding, and 2 = good understanding [interrater reliability = 0.97]). Scores were summed across items and then averaged across raters (range = 0 to 10).

The practical financial knowledge measure was computed by standardizing and averaging the multiple-choice and open-ended scales.

Financial planfulness.

Study members’ financial planfulness at age 45 y was indexed by measuring the number of financial building blocks (property ownership, investments, and retirement planning) they had accrued, their attitudes toward saving (e.g., “Is saving for the future important to you?”), and their savings behavior (e.g., “Have you set aside emergency or rainy day funds that would cover your expenses for 3 months, in case of sickness, job loss, economic downturn, or other emergencies?”).

Credit scores.

Study members’ credit scores were acquired at age 45 y from the Equifax/Veda Company. Of the 938 study members who participated in the age-45 assessment, 724 consented to a credit-rating search and were credit-active in New Zealand in the last five years. The majority of study members who were not active resided overseas; we imputed age-45 credit scores for these individuals based on their scores at the prior assessment wave (age 38 y). Six study members were flagged by Equifax/Veda as insolvent at phase 45; we assigned them a score of 66 (one point less than the lowest score among study members with a credit score). Credit scores ranged from 66 to 996.

Informant-reported financial problems.

At age 45 y, study members were asked to nominate someone “who knew them well” (e.g., friends, partners, and family members). Informants rated the study member on the item “poor money manager” (0 = not a problem, 1 = bit of a problem, and 2 = yes, a problem). Responses were averaged across informants.

Social Preparedness Outcomes.

Social support.

At age 45 y, study members completed the 12-item Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (e.g., “There is a special person who is around when I am in need” [0 = hardly ever, 1 = some of the time, and 2 = often]) (88).

Loneliness.

Study member responses at age 45 y (0 = hardly ever, 1 = some of the time, and 2 = often) to four items adapted from the UCLA Loneliness Scale (e.g., “How often do you feel you lack companionship?”) (89) and one item adapted from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (“How often have you felt lonely in the past week?”) (90) were summed.

Satisfaction with life.

At age 45 y, study members completed the five-item Satisfaction With Life Scale (e.g., “In most ways my life is close to ideal”) (91).

Adult Self-Control, Social Class, and IQ.

Adult self-control.

When study members were 38 and 45 y old, a five-item version of the Conscientiousness scale of the Big Five Personality Inventory (92) was completed by individuals whom study members nominated as informants who knew them well, as well as Dunedin Study personnel who interacted with the study members during their day-and-a-half-long assessment sessions at the Dunedin Study Unit. At each age, responses were averaged across informants and averaged across study personnel. The informant and study personnel Conscientiousness ratings were correlated (rs = 0.36 to 0.62, Ps < 0.0001). To create the adult self-control measure, we performed a principal components analysis on the informant and study personnel Conscientiousness ratings and extracted the first principal component (M = 0, SD = 1), which accounted for 56% of the variance. Adult self-control was correlated with childhood self-control (r = 0.33, P < 0.0001).

Adult social class.

Study members’ socioeconomic status at age 45 y was measured according to the New Zealand Socioeconomic Index 2006 (93), a six-group occupation-based measure of socioeconomic status. Homemakers and others not working in the past year were assigned the socioeconomic status of their most recent occupation, as reported at age 38 y. Study members who had been out of the labor force since age 32 y were assigned the socioeconomic status of their partner; if they did not share a household with a partner, their socioeconomic status was assigned based on their education level.

Adult IQ.

The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-IV (94) was administered to participants at age 45 y, yielding the IQ.

Statistical Analysis.

To be included in analyses, we required that participants have data on childhood self-control, childhood social class, childhood IQ, and at least one outcome measure.

Analyses comprised outcomes in four domains: 1) accelerated aging, 2) health preparedness, 3) financial preparedness, and 4) social preparedness. In addition to analyzing each outcome individually, we performed a principal components analysis on the outcomes within each domain and extracted the first principal component for each domain (SI Appendix, Table S3).

We used linear regression to test whether childhood self-control predicted each principal component and individual outcome and to test whether childhood social class and childhood IQ explained these effects. We used correlation analysis to estimate the stability in self-control, social class, and IQ from childhood to adulthood. Analyses were adjusted for sex. Statistical significance was evaluated using an alpha level of 0.05. No adjustment to the alpha level was made because we tested prespecified hypotheses, analyzed outcomes that were correlated with each other (e.g., multiple indicators of accelerated aging), reported results for all tests, and did not test a universal null hypothesis (95).

Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.). Analyses were checked for reproducibility by an independent data analyst who recreated the code by working from the manuscript and applied it to a fresh copy of the dataset. The project and analysis plan were preregistered (2019; https://sites.google.com/site/dunedineriskconceptpapers/home/dunedin-approved).

Acknowledgements

Research was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (AG032282, AG049789), the UK Medical Research Council (P005918), and the Jacobs Foundation. The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study is supported by the New Zealand Health Research Council and the New Zealand Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. L.S.R.-R. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD007376). M.E. was supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (DGE-1644868). L.J.H.R. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Lundbeck Foundation (R288-2018-380). J.W. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the AXA Research Fund. We thank the Dunedin Study members, Unit research staff, Pacific Radiology Group staff, and Study founder Phil Silva.

Data Availability.

The Dunedin Study data are not publicly available due to lack of informed consent and ethical approval but are available on request by qualified scientists. Requests require a concept paper describing the purpose of data access, ethical approval at the applicant’s institution, and provision for secure data access. We offer secure access on the Duke University, Otago University, and King’s College London campuses. All data analysis scripts and results files are available for review.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

31

32

33

34

35

36

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

Childhood self-control forecasts the pace of midlife aging and preparedness for old age

Childhood self-control forecasts the pace of midlife aging and preparedness for old age