Edited by Andrew L. Ferguson, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Mehran Kardar February 27, 2021 (received for review November 5, 2020)

Author contributions: G.I., A.M.W., T.M., and A.N. designed research; G.I., A.M.W., T.M., and A.N. performed research; G.I. analyzed data; and G.I., A.M.W., T.M., and A.N. wrote the paper.

1A.M.W., T.M., and A.N. contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

The adaptive immune system relies on many types of B and T cells, whose functions are reflected in the distinct molecular features of their receptor sequences. Here, we introduce an inference framework, soNNia, which integrates interpretable knowledge-based models of immune receptor generation with flexible and powerful deep learning approaches to characterize sequence determinants of receptor function. Using soNNia, we characterize sequence-specific selection associated with receptors harvested from different cell types and tissues. We quantify synergetic interactions between the molecular features of the paired chains making up the receptor. Lastly, we develop a selection-based classifier to identify T cells specific to distinct pathogenic epitopes. Our approach provides a molecular understanding for how sequence determines the specific functionality of immune receptors.

Subclasses of lymphocytes carry different functional roles to work together and produce an immune response and lasting immunity. Additionally to these functional roles, T and B cell lymphocytes rely on the diversity of their receptor chains to recognize different pathogens. The lymphocyte subclasses emerge from common ancestors generated with the same diversity of receptors during selection processes. Here, we leverage biophysical models of receptor generation with machine learning models of selection to identify specific sequence features characteristic of functional lymphocyte repertoires and subrepertoires. Specifically, using only repertoire-level sequence information, we classify CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, find correlations between receptor chains arising during selection, and identify T cell subsets that are targets of pathogenic epitopes. We also show examples of when simple linear classifiers do as well as more complex machine learning methods.

The adaptive immune system in vertebrates consists of highly diverse B and T cells whose unique receptors mount specific responses against a multitude of pathogens. These diverse receptors are generated through genomic rearrangement of V-, D-, and J-genes, and sequence insertions and deletions at the junctions, a process known as V(D)J recombination (1, 2). Recognition of a pathogen by a T cell receptor (TCR) or B cell receptor (BCR) is mediated through molecular interactions between an immune receptor protein and a pathogenic epitope. TCRs interact with short protein fragments (peptide antigens) from the pathogen that are presented by specialized pathogen-presenting major histocompatibility complexes (MHCs) on cell surface. BCRs interact directly with epitopes on pathogenic surfaces. Upon an infection, cells carrying those specific receptors that recognize the infecting pathogen become activated and proliferate to control and neutralize the infection. A fraction of these selected responding cells later contributes to the memory repertoire that reacts more readily in future encounters. Unsorted immune receptors sampled from an individual reflect both the history of infections and the ongoing responses to infecting pathogens.

Before entering the periphery where their role is to recognize foreign antigens, the generated receptors undergo a twofold selection process based on their potential to bind to the organism’s own self-proteins. On one hand, they are tested to not be strongly self-reactive (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, they must be able to bind to some of the presented molecules to assure minimal binding capabilities. This pathogen-unspecific selection, known as thymic selection for T cells (6) and the process of central tolerance in B cells (7), can prohibit over 90% of generated receptors from entering the periphery (6, 8, 9).

![Inference of functional selection models for immune receptor repertoires. (A) TCR α and β chains are stochastically rearranged through a process called V(D)J recombination. Successfully rearranged receptors undergo selection for binding to self-pMHCs (self peptides loaded onto major histocompatibility complexes). Receptors that bind too weakly or too strongly are rejected, while intermediately binding ones exit the thymus and enter peripheral circulation. Development of BCRs follows similar stages of stochastic recombination and selection. (B) We model these two processes independently. The statistics of the V(D)J recombination process described by the probability of generating a given receptor sequence σ, Pgen(σ), are inferred using the IGoR software (3). Pgen(σ) acts as a baseline for the selection model. We then infer selection factors Q, which act as weights that modulate the initial distribution Pgen(σ). We infer two types of selection weights: linear in log space [using the SONIA software (4)] and nonlinear weights using a DNN, in the soNNia software presented here. Nonlinear selection weights are more flexible than linear ones. (C) Pipeline of the algorithm: Pgen is inferred from unproductive sequences using IGoR. Selection factors for both the linear and nonlinear models are inferred from productive sequences by maximizing their log-likelihood L, which involves a normalization term calculated by sampling unselected sequences generated by the OLGA software (5). (D) In both selection models, the amino acid composition of the CDR3 is encoded by its relative distance from the left and right borders (left–right encoding). (E) After inferring repertoire-specific selection factors, repertoires are compared by computing, for example, log-likelihood ratios r(x).](/dataresources/secured/content-1766030659806-bb5c638f-4bf9-4374-be60-c35e58d6a208/assets/pnas.2023141118fig01.jpg)

Inference of functional selection models for immune receptor repertoires. (A) TCR and

Additionally to receptor diversity, T and B cell subtypes are specialized to perform different functions. B and T cells in the adaptive immune system are differentiated from a common cell type, known as lymphoid progenitor. T cells differentiate into cell subtypes identified by their surface markers, including helper T cells (CD4+), killer T cells (CD8+) (6), and regulatory T cells (Tregs; CD4+ FOXP3+) (10), each of which can be found in the nonantigen primed naive or memory compartment. The memory compartment can be further divided into subtypes, such as effector, central, or stem cell-like memory cells, characterized by different lifetimes and roles. B cells develop into, among other subtypes, plasmablasts and plasma cells, which are antibody factories, and memory cells that can be used against future infections. These cell subtypes perform distinct functions, react with different targets, and hence, experience different selection pressures. Here, we ask whether these different functions and selection pressures are reflected in their receptors’ sequence compositions.

Recent progress in high-throughput immune repertoire sequencing both for single-chain (111213–14) and paired-chain (1516–17) BCRs and TCRs has brought significant insight into the composition of immune repertoires. Based on such data, statistical inference techniques have been developed to infer biophysically informed sequence-based models for the underlying processes involved in generation and selection of immune receptors (34–5, 18). Machine learning techniques have also been used to infer deep generative models to characterize the T cell repertoire composition as a whole (21), as well as discriminate between public and private B cell clones based on complementarity-determining region 3 (CDR3) sequence (22, 23). While biophysically informed models can still match and even outperform machine learning techniques (24), deep learning models can be extremely powerful in describing functional subsets of immune repertoires, for which we lack a full biophysical understanding of the selection process.

Here, we introduce a framework that uses the strengths of both biophysical models and machine learning approaches to characterize signatures of differential selection acting on receptor sequences from subsets associated with specific function. Specifically, we leverage biophysical tools to model what we know (e.g., receptor generation) and exploit the powerful machinery of deep neural networks (DNNs) to model what we do not know (e.g., functional selection). Using the nonlinear and flexible structure of the DNNs, we characterize the sequence properties that encode selection of the specificity of the combined chains during receptor maturation in

Results

Neural Network Models of TCR and BCR Selection.

Previous work has inferred biophysically informed models of V(D)J recombination underlying the generation of TCRs and BCRs (3, 30). In brief, these models are parametrized according to the probabilities by which different V, D, J genes are used and base pairs are inserted in or deleted from the CDR3 junctions to generate a receptor sequence. We infer the parameters of these models using the IGoR software (3) from unproductive receptor sequences, which are generated but due to a frameshift or insertion of stop codons, are not expressed and hence, are not subject to functional selection. The inferred models are used to characterize the generation probability of a receptor sequence

The amino acid sequence of an immune receptor protein determines its function. To identify sequence properties that are linked to function, we compare the statistics of sequence features

In soNNia, we divide the sequence features

The baseline ensemble

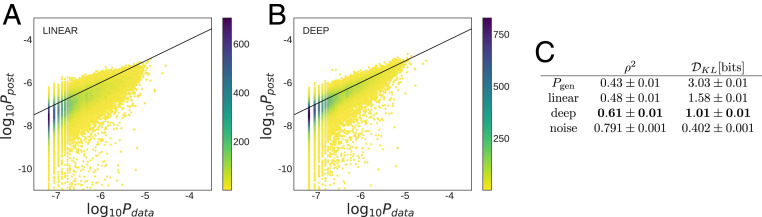

Deep Nonlinear Selection Model Best Describes Functional TCR Repertoire.

First, we systematically compare the accuracy of the (nonlinear) soNNia model with linear SONIA (4) (Fig. 1B) by inferring selection on TCR

We randomly split the pooled dataset into a training and a test set of equal sizes and trained both a SONIA and a soNNia selection model on the training set (Methods and Fig. 1C). Our inference is highly stable, and the selection models are reproducible when trained on subsets of the training data (SI Appendix, SI Text and Fig. S2).

To assess the performance of our selection models, we compared their inferred probabilities

Performance of selection models on TCR repertoires. Scatterplot of observed frequency,

We observe a substantial improvement of selection inference for the generalized selection model soNNia with

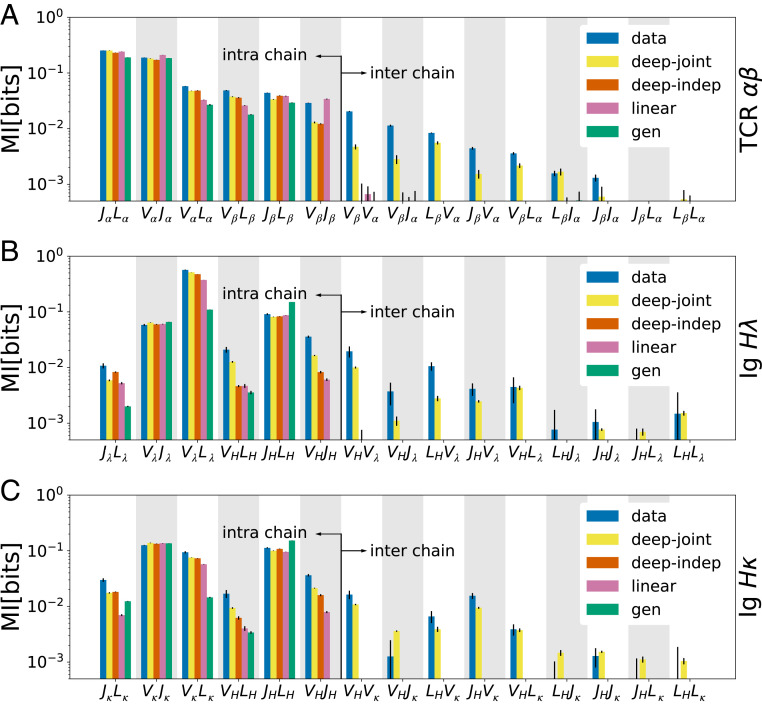

Intra- and Interchain Interactions in TCRs and BCRs.

TCRs are disulfide-linked membrane-bound proteins made of variable

We first aimed to quantify dependencies between chains by reanalyzing recently published single-cell datasets: TCR

Inference of selection on intra- and interchain receptor features. Mutual information between pairs of major intra- and interchain features (

Both TCRs and BCRs have intra- and interchain correlations of sequence features, with stronger empirical mutual dependencies present within chains (Fig. 3).

To account for these dependencies between chains, we generalize the selection model of Eq. 1 to pairs,

Analogously to single chains, we first define a linear selection model specified by

We trained these three classes of models on each of the TCR

The inferred selection on correlated interchain receptor features is consistent with previous analyses in TCRs (34353637–38) and is likely due to the synergy of the two chains interacting with self-antigens presented during thymic development for TCRs and preperipheral selection (including central tolerance) for BCRs or later when recognizing antigens in the periphery. Notably, the largest interchain dependencies and synergistic selection are associated with the V-gene usages of the two chains (Fig. 3), which encode a significant portion of antigen-engaging regions in both TCRs and BCRs.

Our results show that the process of selection in BCRs is restrictive, in agreement with previous findings (7), significantly increasing interchain feature correlations. Notably, the increase in correlations (difference between green and other bars) due to selection is larger in naive B cells than in unsorted (memory and naive) T cells. However, the selection strengths inferred by our models should not be directly compared with estimates of the percentage of cells passing preperipheral selection:

Lastly, to quantify the diversity of immune receptor repertoires, we compared the entropy of unpaired- and paired-chain repertoires in SI Appendix, Table S1 (SI Appendix, SI Text). These entropy measures suggest a repertoire size (i.e., a typical number of amino acid sequences) of about

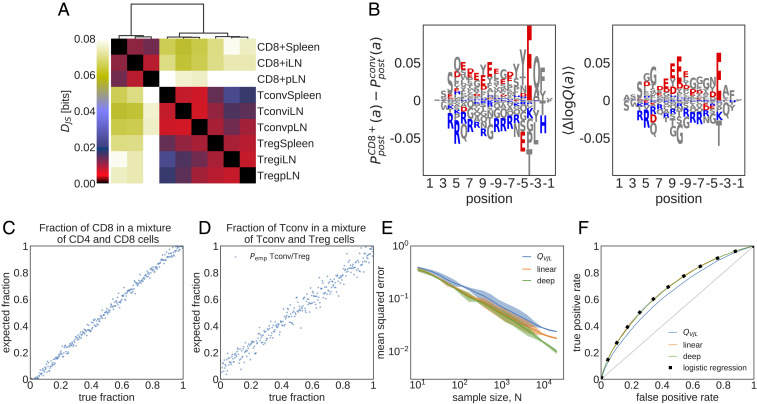

Cell Type- and Tissue-Specific Selection on T Cells.

During maturation in the thymus, T cells differentiate into two major cell types: cytotoxic (CD8+) and helper (CD4+) T cells. CD8+ cells bind peptides presented on MHC class I molecules that are expressed by all cells, whereas CD4+ cells bind peptides presented on MHC class II molecules, which are only expressed on specialized antigen presenting cells. Differences in sequence features of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells should reflect the distinct recognition targets of these receptors. Although these differences have already been investigated in refs. 36 and 42, we still lack an understanding as how selection contributes to the differences between CD8+ and CD4+ TCRs. In addition to functional differentiation at the cell-type level, T cells also migrate and reside in different tissues, where they encounter different environments and are prone to infections by different pathogens. As a result, we expect to detect tissue-specific TCR preferences that reflect tissue-specific T cell signatures.

To characterize differential sequence features of TCRs between cell types in different tissues, we pool unique TCRs from nine individuals (from ref. 42) sorted into three cell types (CD4+ conventional T cells [Tconvs], CD4+ Tregs, and CD8+ T cells) and harvested from three tissues (pancreatic draining lymph nodes [pLNs], “irrelevant” nonpancreatic draining lymph nodes [iLNs], and spleen).

Training a nonlinear soNNia model (Fig. 1C) for each subset leads to overfitting issues due to limited data. To solve this problem, we train the model in two steps. First, we use the unfractionated data from ref. 43 to construct a shared baseline for all repertoire subsets. We then learn independent linear SONIA models for each repertoire subset so that the inferred

Cell type- and tissue-specific selection on TCRs. (A) Jensen–Shannon divergences (

To quantify differential selection on subrepertoires, we use Jensen–Shannon divergence

Examining the linear selection factors of the SONIA model trained atop

One key difference between CD4+ and CD8+ TCRs amino acid composition is their CDR3 charge preferences. We observe an overrepresentation of positively charged (Lysine, K, and Arginine, R) and suppression of negatively charged (Aspartate, D, and Glutamate, E) amino acids in CD4+ TCRs compared with CD8+ TCRs (Fig. 4B), consistent with previous observations (44). These charge preferences arise due to differential selection on the two subtypes (Fig. 4B), indicating broad differences between amino acid features of peptide–MHC-I and peptide–MHC-II complexes, which respectively interact with CD8+ and CD4+ TCRs. For example, a statistical survey of peptides presented by different MHC classes shows that MHC-I molecules tend to present more positively charged peptides compared with MHC-II molecules—a bias that is complementary to the charge preferences of the respective TCR subtypes (45).

Decomposing Unsorted Repertoires Using Selection Models.

Knowing

Previous work has used differential V- and J-gene usage and CDR3 length to characterize the relative fraction of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in an unfractionated repertoire (47). The log-likelihood function in Eq. 4 provides a principled approach for inferring cell-type composition using selection factors that capture the differential receptor features of each subrepertoire, including but not limited to their V and J usage and CDR3 length and amino acid preferences.

To test the accuracy of our method, we formed a synthetic mixture of previously sorted CD4+ [Tconv from spleen (42)] and CD8+ [from spleen (42)] receptors with different proportions and show that our selection-based inference can accurately recover the relative fraction of CD8+ in the mix (Fig 4C). Our method can also infer the proportion of Treg cells in a mixture of Tconv and Treg CD4+ cells from spleen (Fig. 4D), which is a much harder task since these subsets are very similar (Fig. 4A). The accuracy of the inference depends on the size of the unfractionated data, with a mean expected error that falls below 1% for datasets with size

Our method uses a theoretically grounded maximum likelihood approach, which includes all of the features captured by the soNNia model. Nonetheless, a simple linear selection model with only V- and J-gene usage and CDR3 length information (blue line in Fig. 4E), analogous to the method used in ref. 47, reliably infers the composition of the mixture repertoire. Additional information about amino acid usage in the linear SONIA model results in moderate but significant improvement (orange line in Fig. 4E). The accuracy of the inference is insensitive to the choice of the baseline model for receptor repertoires: Using the empirical baseline from ref. 43 (Fig. 4E) or

The method can be extended to the decomposition of three or more subrepertoires. To illustrate this, we inferred the fractions of Tconv, Treg, and CD8+ cells in synthetic unfractionated repertoires from spleen, showing an accuracy of

Computational Sorting of CD4+ and CD8+ TCRs.

Selection models are powerful in characterizing the broad statistical differences between distinct functional subsets of immune receptors, including the CD4+ and CD8+ TCRs (Fig. 4A). A more difficult task, which we call computational sorting, is to classify individual receptors into functional classes based on their sequence features. In other words, how accurately can one classify a given receptor as a member of a functional subset (e.g., CD4+ or CD8+ TCRs)?

We use selection models inferred for distinct subrepertoires

For comparison, we also used a common approach for categorical classification and optimized a linear logistic classifier that takes receptor features (similar to the selection model) as input and classifies receptors into CD8+ or CD4+ cells. The model predicts the probability that sequence

It should be emphasized that despite comparable performances, our fully linear selection-based method provides a biologically interpretable basis for subtype classification, in contrast to black box approaches (36). For example, the relative importance of different sequence features (i.e., CDR3 length, V/J gene identity, and amino acid composition) for CD4+ vs. CD8+ classification is shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9.

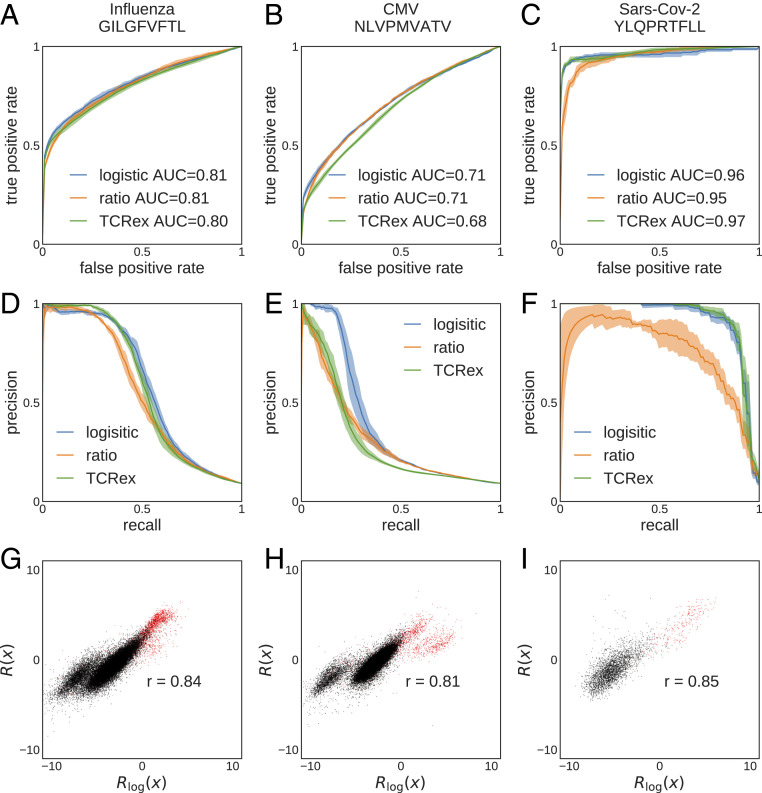

Classification of TCRs Targeting Distinct Antigenic Epitopes.

Recognition of a pathogenic epitope by a TCR is mediated through molecular interactions between the two proteins. The strength of this interaction depends on the complementarity of a TCR against an antigen presented by an MHC molecule on the T cell surface. Recent growth of data on paired TCRs and their target epitopes (26, 48) has led to the development of machine learning methods for TCR–epitope mapping (25262728–29). A TCR–epitope map is a classification problem that determines whether a TCR binds to a specific epitope. We use our selection-based classifier (Eq. 5) to address this problem. We determine the target ensemble

We performed classification for the following CD8+-specific epitopes, presented on HLA-A*02 molecules: 1) the influenza GILGFVFTL epitope (with

Selection-based prediction of epitope specificity for TCR. TCRs are classified based on their reactivity to three pathogenic epitopes (columns), using three classification methods: TCRex, log-likelihood ratio (Eq. 5), and linear logistic regression (Eq. 6). (A–C) ROC curves and (D–F) precision-recall curves for (A and D) influenza epitope GILGFVFTL (

The TCR–epitope mapping is a highly unbalanced classification problem, where reactive receptors against a specific epitope comprise a very small fraction of the repertoire [less than

Discussion

Previous work has developed linear selection models to characterize the distribution of productive TCRs (4). Here, we generalized on these methods by using DNNs implemented in the soNNia algorithm to account for nonlinearities in feature space and have improved the statistical characterization of TCR repertoires in a large cohort of individuals (33).

Using this method, we modeled the selective pressure on paired chains of T and BCRs and found that the observed cross-chain correlations, even if limited, could be partially reproduced with our model (Fig. 3). These observed interchain correlations are likely due to the synergy of the two chains interacting with self- and nonself-antigens, which determine the selection pressure that shapes the functional TCR and BCR repertoires.

We systematically compared T cell subsets and showed that our method identifies differential selection on CD8+ T cells, CD4+ conventional T cells, and CD4+ regulatory T cells. TCRs belonging to families with more closely related developmental paths (i.e., CD4+ regulatory or conventional cells) have more similar selection features, which differentiate them from cells that diverged earlier (CD8+). Cells with similar functions in different tissues are in general similar, with the exception of spleen CD8+ that stands out from lymph node CD8+. These differences capture broad differential preferences of CD8+ and CD4+ TCRs, which can arise from their distinct structural features complementary to their different targets (i.e., peptide–HLAI and peptide–HLAII complexes). A next step would be to uncover more fine-grained differential features, associated with the distinct pathogenic history or HLA composition of different individuals.

One application of the soNNia method is to utilize our selection models to infer ratios of cell subsets in unsorted mixtures, following the proposal of Emerson et al. (47). Consistently with previous results, we find that the estimated ratio of CD4+/CD8+ cells in unsorted mixtures achieves precision of the order of

As a harder task, we were also able to decompose the fraction of regulatory vs. conventional CD4+ T cells, showing that receptor composition encodes not just signatures of shared developmental history—receptors of these two CD4+ subtypes are still much more similar to each other than to CD8+ receptors—but also, function: Tregs down-regulate effector T cells and curb an immune response, creating tolerance to self-antigens and preventing autoimmune diseases (10), whereas Tconvs assist other lymphocytes, including activation of differentiation of B cells. Since our analysis is performed on fully differentiated peripheral cells, we cannot say at what point in their development these CD4+ T cells are differentially selected. Data from regulatory and conventional T cells at different stages of thymic development could identify how their receptor composition is shaped over time.

During thymic selection, cells first rearrange a

In recent years, multiple machine learning methods have been proposed in order to predict antigen specificity of TCRs: TCRex (28, 49), DeepTCR (50), netTCR (51), ERGO (52), TCRGP (27) and TcellMatch (53). All these methods have explored the question in slightly different ways and made comparisons with each other. However, with the sole exception of TcellMatch (53), none of the above methods compared their performance with a simple linear classifier. TcellMatch (53) does not explicitly compare with other existing methods but implicitly compares various neural network architectures. We thus directly compared a representative of the above group of machine learning models, TCRex, with a linear logistic classifier and with the log-likelihood ratio obtained by training two SONIA models on the same set of features. We found that the three models performed similarly (Fig. 5), consistent with the view that amino acids from the CDR3 loop interact with the antigenic peptide in an additive way. This result complements similar results in ref. 53, where a linear classifier gave comparable results to DNN architectures.

The linear classifier based on likelihood ratios achieves state-of-the-art performance both in discriminating CD4+ from CD8+ cells (Fig. 4F) and in predicting epitope specificity (Fig. 5). However, unlike other classifiers, its engine can be used to generate positive and negative samples. Thus, characterizing the distributions of positive and negative examples is more data demanding than mere classification. For this reason, pure classifiers are generally expected to perform better but lack the ability to sample new data. Our analysis complements the collection of proposed classifiers by adding a generative alternative that is grounded on the biophysical process of T cell generation and selection. This model is simple and interpretable and performs well with large amounts of data.

The epitope discrimination task discussed here and in previous work focuses on predicting TCR specificity to one specific epitope. A long-term goal would be to predict the affinity of any TCR–epitope pair. However, currently available databases (26, 48) do not contain sufficiently diverse epitopes to train models that would generalize to unseen epitopes (53). A further complication is that multiple TCR specificity motifs may coexist even for a single epitope (29, 54), which cannot be captured by linear models (55). Progress will be made possible by a combination of high-throughput experiments assaying many TCR–epitope pairs (56) and machine learning-based techniques such as soNNia.

In summary, we show that nonlinear features captured by soNNia capture more information about the initial and peripheral selection processes than linear models. However, DNN methods such as soNNia suffer from the drawback of being data hungry and show their limitations in practical applications where data are scarce. Nonetheless, with the rapid growth of functionally annotated datasets, we expect soNNia to be more readily used for inference of nonlinear selection on immune receptor sequences. Such nonlinearity is expected as it would reflect the ubiquitous epistatic interactions between residues of a receptor protein that encode for a specific function. In a more general context, soNNia is a way to integrate more basic but interpretable knowledge-based models and more flexible but less interpretable deep learning approaches within the same framework.

Methods

Data Description.

In this work, we used different datasets to evaluate selection on TCR and BCR features.

1)To quantify the accuracy of the soNNia model (Fig. 2), we used the TCR

2)To characterize selection on paired-chain receptors (Fig. 3), we analyzed TCR

3)To characterize differential sequence features of TCRs between cell types in different tissues (Fig. 4), we pooled unique TCRs from nine healthy individuals from ref. 42, sorted into CD4+ Tconvs, CD4+ Tregs, and CD8+ T cells, harvested from three tissues: pLNs (

Quantifying Accuracy of Selection Models.

To assess the performance of our selection models, we compare their inferred probabilities

Comparing Selection on Different Subrepertoires.

To characterize differences in subrepertoires due to selection, we evaluate the Jensen–Shannon divergence

Acknowledgements

We thank Phil Bradley for helpful discussions about differential charge preferences of CD4+ and CD8+ TCRs. This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant SFB1310 for Predictability in Evolution (G.I., A.M.W., and A.N.), Max Planck Research Group funding through the Max Planck Society (G.I. and A.N.), the Royalty Research Fund from the University of Washington (A.N.), European Research Council Consolidator Grant 724208 (G.I., A.M.W., and T.M.), and Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant ANR-19-CE45-0018 (G.I., A.M.W., and T.M.).

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

2

3

4

5

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

Deep generative selection models of T and B cell receptor repertoires with soNNia

Deep generative selection models of T and B cell receptor repertoires with soNNia