Edited by Alexis T. Bell, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved January 25, 2021 (received for review October 25, 2020)

Author contributions: H.W. and K.S. designed research; H.W. performed research; H.W. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; H.W. analyzed data; and H.W. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

We demonstrate an approach to generate a new type of X-ray imaging mode, which is called omnidirectional X-ray differential phase imaging. The proposed method enables us to detect the subtle phase changes in all directions of the imaging plane, which complements conventional X-ray imaging methods with information that they cannot provide. Importantly, the omnidirectional dark-field images can also be simultaneously retrieved for studying a wide range of complicated samples, particularly strongly ordered systems. The extracted information will not only provide insights into the microarchitecture of materials, but also enrich our understanding the macroscopic behavior. The presented technique could potentially open up numerous practical imaging applications in both biomedical research and materials science.

Ever since the discovery of X-rays, tremendous efforts have been made to develop new imaging techniques for unlocking the hidden secrets of our world and enriching our understanding of it. X-ray differential phase contrast imaging, which measures the gradient of a sample’s phase shift, can reveal more detail in a weakly absorbing sample than conventional absorption contrast. However, normally only the gradient’s component in two mutually orthogonal directions is measurable. In this article, omnidirectional differential phase images, which record the gradient of phase shifts in all directions of the imaging plane, are efficiently generated by scanning an easily obtainable, randomly structured modulator along a spiral path. The retrieved amplitude and main orientation images for differential phase yield more information than the existing imaging methods. Importantly, the omnidirectional dark-field images can be simultaneously extracted to study strongly ordered scattering structures. The proposed method can open up new possibilities for studying a wide range of complicated samples composed of both heavy, strongly scattering atoms and light, weakly scattering atoms.

Over the past two decades, various X-ray directional differential phase contrast and dark-field imaging techniques have been developed for applications in nondestructive testing, biomedical imaging, and materials science (12345–6). The X-ray differential phase is directly linked to the local gradient of the sample's phase shift. Since the phase shift term is much larger than the absorption term for materials composed of light elements, X-ray differential phase imaging offers high contrast at a lower radiation dose than conventional absorption contrast imaging requires. In addition, X-ray dark-field images describe the scattering power due to the structural variation and density fluctuation. Importantly, directional X-ray dark-field imaging detects the orientation of anisotropic structures at micrometer scale and provides valuable information about the scattering power of samples (789–10). Sometimes, directional dark-field imaging can fail to pick up the scattering of some weakly absorbing samples, while X-ray differential phase contrast imaging can show these weak signals more clearly. Therefore, these two techniques can provide complementary information to each other.

However, directional differential phase contrast and dark-field imaging can measure only the component of electron density changes and small-angle scattering in the scanning direction. As a result, the risk of overlooking structures with strong but varying orientation within the sample is high (11, 12). Therefore, it will be desirable to generate the omnidirectional phase shift changes or dark-field signals to pick up detailed information along all directions. To retrieve the omnidirectional dark-field signals, advanced phase gratings and absorption masks have been proposed and tested on anisotropic microstructures (131415–16), but the need for such special optics, along with stringent experimental setup and poor spatial resolution, has restricted its application. In principle, the omnidirectional differential phase images could be retrieved by scanning the optics in various directions or rotating the samples (17, 18), but this would increase the complexity of the experimental setup and dramatically prolong the data acquisition time.

Recently, the speckle-based imaging technique has been developed and become popular for its great simplicity and remarkable performance (19, 20). The horizontal and vertical differential phase information can be retrieved from either a single speckle image or a stack of speckle images, depending on whether speed or spatial resolution is more important. In addition, the directional dark-field image can be retrieved from the one-dimensional (1D) speckle scanning technique (10), while two separated scans are required to obtain the orthogonal dark-field images.

In this study, we describe an algorithm to extract both the omnidirectional differential phase and dark-field signal with a randomly structured wavefront modulator, such as a sandpaper. To achieve the omnidirectional information and minimize the necessary radiation dose, the sandpaper is scanned along a spiral trajectory. Fourier analysis is then performed to obtain the phase changes and scattering signal of the sample in all directions of the imaging plane. In addition, the proposed method shows great potential to decouple the isotropic and anisotropic scattering signals by analyzing the omnidirectional dark-field images.

Method and Data Processing

A speckle pattern (in the plane) can be generated by inserting a randomly structured wavefront modulator into the beam. Several speckle-based methods for collecting high-resolution phase contrast and dark-field images have been investigated by scanning the modulator in different directions (21222324–25). For the two-dimensional (2D) speckle scanning technique, the modulator was scanned along horizontal

To avoid the 2D raster scan, speckle vector tracking (SVT) and unified modulated pattern analysis (UMPA) methods have been proposed independently by scanning the modulator with nonuniform step size (22, 25). Both the horizontal and vertical differential phase contrast images and dark-field images can be generated from the UMPA and SVT methods. However, neither method can provide the directional dark-field information since the speckle data analysis is carried out within a subset window

The 1D speckle scanning approach has been developed to provide directional dark-field image by scanning the modulator along one direction (10, 23). The virtual speckle image (

To circumvent the above limitations, we propose an alternative approach to analyze the speckle data and achieve differential phase and dark-field images in all directions. In order to reduce the image numbers and data acquisition time, the spiral scan method is used for high-speed ptychography experiments (27). Similarly, in our work, we scan the modulator in a spiral trajectory

One stack of reference speckle images

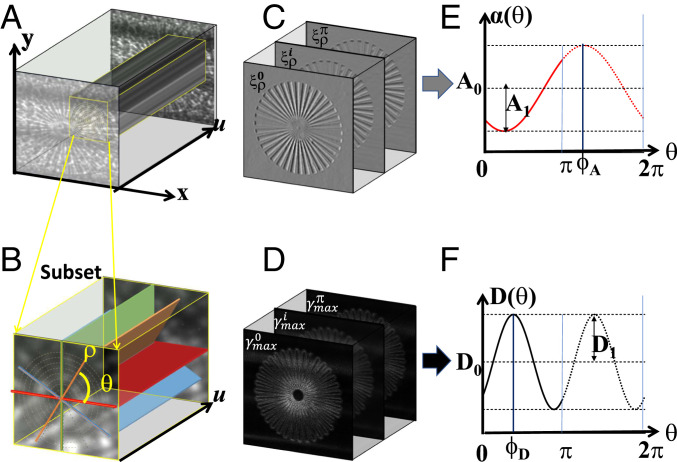

A schematic illustration of the extraction of the directional differential phase and dark-field images of a sample star pattern. (A) The collected stack of speckle images in Cartesian coordinates. (B) The select subset from A is transformed into polar coordinates. (C and D) The extracted speckle displacement

Here,

The correlation coefficient maps

Cross-correlation is represented by the pentagram symbol

The 1D speckle scanning technique can be treated as a special case

where

The directional dark-field images do not distinguish between scattering at orientation angles

Here, the Fourier coefficients

The horizontal and vertical differential phase images

Furthermore, the phase shift Φ induced by the sample can then be reconstructed from the two transverse phase gradients

where

Hence, the phase shift

Experiment 1.

The principle of the proposed technique was validated by experimental measurements at the Diamond Light Source’s B16 Test beamline (30). X-rays with an energy of 15 keV were selected from the bending magnet source using a double-multilayer monochromator. As shown in Fig. 1A, a piece of sandpaper with a grain size of 5 µm was chosen as a modulator, which was mounted on a 2D piezostage and located 45 m from the X-ray source. The sample was fixed on a motorized stage 375 mm downstream of the modulator. The distance between the sample and detector was L = 955 mm. Images of the speckle pattern were collected using a high-resolution X-ray camera composed of a pco.edge charge-coupled device (CCD) detector and a microscope objective with a LuAG (Ce) scintillator (31). As a demonstration of the capabilities of the proposed technique, a phantom with 36 actinomorphic star patterns (QRM) was purposefully chosen because its features are distributed along all the directions in the imaging plane. In addition, a woodlouse sample was also tested because it has complex biological structures containing both isotropic and anisotropic scattering properties.

To image the star-pattern phantom, the camera system was focused with an effective pixel resolution of 0.5 μm × 0.5 μm. The sandpaper was scanned with a spiral trajectory over a range of 100 µm, with n = 50 images recorded. Two stacks of speckle images were taken, one without and one with the sample in the X-ray beam. The exposure time per speckle image was 2 s. Fig. 1A shows the stack of speckle images with the sample present. The selected window is then transformed in polar coordinate and is shown in Fig. 1B. The virtual speckle stack is then generated along the polar direction ρ and the spiral scan direction

Data processing was performed using a program run in MATLAB version 2020b. A Gaussian filter was applied to the raw speckle images to minimize the speckle noise and improve the tracking accuracy. The MATLAB code was run using a standard desktop computer (Dell with Intel Xeon 3.70-GHz processor and 64-GB memory), and the data processing is equally distributed over eight workers with Parallel Computing Toolbox. It took 26 min for processing the phantom with region of interest 950 × 950 pixels by using the above parameters.

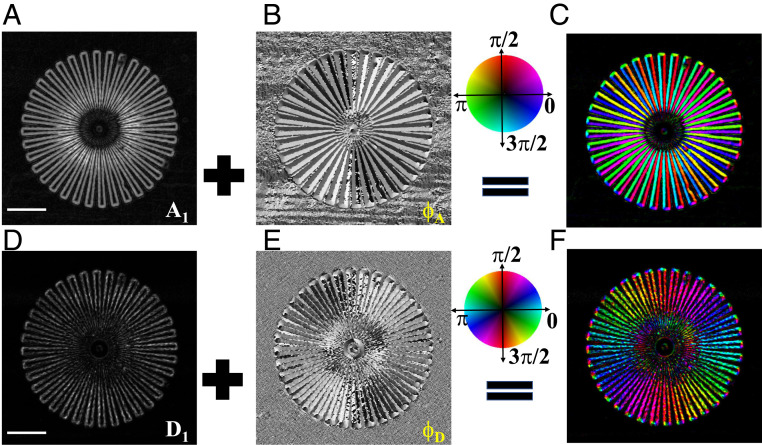

Fig. 2 shows the retrieved differential phase amplitude

(A and B) The retrieved amplitude

Experiment 2.

A woodlouse was then selected to demonstrate the applicability of the proposed method for the study of biological samples with complicated structures. The specimen was clamped inside a plastic film box so that the X-rays can pass through the sample with minimum scattering and phase distortion from the container. The effective pixel resolution of the imaging system was increased to 3.9 μm × 3.9 μm to ensure the entire sample was within the field of view, and the exposure time was reduced to 500 ms per frame. The differential phase and phase images are presented in Fig. 3. The woodlouse exhibits a few distinctive features in various image modes. The same speckle scanning and processing parameters and procedures as the star phantom were used for the woodlouse sample. As shown in Fig. 3 A and B the higher scattering signals for the edge of the lateral plate are shown in both the average

![(A and B) The retrieved average D0 and amplitude D1 of dark-field signal of a woodlouse sample. The gray color indicates that the normalized D0 and D1 changes from 0 (dark) to 1 (bright). (C) The constructed omnidirectional dark field, as rendered in an HSV color scheme. (D and E) The main orientation ϕA[0, 2π] and normalized amplitude A1[0, 1] of differential phase. (F) The constructed omnidirectional differential phase, as rendered in an HSV color scheme. (G and H) The calculated horizontal and vertical differential phase from A1 and ϕA. The gradient varies from −3 to 3 μrad (bright). (I) The reconstructed phase from G and H, in which the phase ranges from −60 (dark) to 60 rad (bright). (Scale bar, 0.5mm.)](/dataresources/secured/content-1765989029814-d1dbe165-d8d9-4466-a2bf-b6a4f9cbbddd/assets/pnas.2022319118fig03.jpg)

(A and B) The retrieved average

The calculated horizontal and vertical differential phase images are shown in Fig. 3 G and H. The vertical features along the lateral plate are clearly visible in the horizontal differential phase image

As shown in Fig. 3I, the phase image provides a comprehensive overview of the internal structure of the woodlouse. For example, the retained foods from the thorax are clearly visible in both the reconstructed phase map (Fig. 3I) and the corresponding average dark-field image (Fig. 3A). By contrast, the soft tissues such as the uropod and epimera are barely visible in the dark-field images, yet can be clearly distinguished from the surrounding lateral plate in the omnidirectional differential phase image (Fig. 3F).

Discussion and Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated that the omnidirectional differential phase and dark-field images can be simultaneously extracted from a single dataset with the use of a simple modulator. We have shown that the retrieved multimodal images from the proposed approach can reveal a wide variety of internal structures within one sample. The directional differential phase images reveal the directional dependence of the weakly absorbed features, complementing the directional dark-field images. In addition, the retrieved main orientation image of the directional differential phase can further improve the contrast for thin samples, while the amplitude image of the directional differential phase shows the phase changes along all directions in the imaging plane at once. Moreover, high-quality horizontal and vertical differential phase images and phase shifts can be automatically calculated from the above amplitude and main orientation images. Unlike in the previously reported 1D dark-field imaging technique, the isotropic and anisotropic scattering signals from underlying microstructure can be potentially decoupled by applying Fourier analysis to the omnidirectional dark-field images. The omnidirectional differential phase and dark-field images resolve the directional dependence of complex microstructures, which is inaccessible to conventional X-ray imaging techniques.

Compared to the other techniques, high-precision optics is not required and rotation of the samples or the optics can be avoided. Only a piece of sandpaper is required as a wavefront modulator to generate the speckle pattern. In addition to the low cost, robustness, and availability in large sizes, sandpaper with different grain sizes can be chosen to suit the spatial resolution requirement of the detector. In addition, the modulator can be replaced with a strongly absorbing mask for the study of thick, dense materials with high-energy X-rays (32, 33). The spatial correlation length can be adjusted to study variable feature sizes by choosing a suitable window size. It should be noted that it is not essential to scan the modulator with a spiral trajectory for the proposed method. In fact, it can be scanned with either a random step or a constant step along the transverse directions. The data collected from the SVT and UMPA can be used to produce omnidirectional differential phase images and dark-field images by the proposed algorithm. The experimental parameters can also be optimized according to the requirements on speed or sensitivity. Although the proposed technique has been demonstrated with synchrotron radiation, it can be potentially transferred to laboratory X-ray microfocus sources for wider application (23, 34, 35). The radiation dose can be further reduced by using a highly efficient flat-panel detector. Finally, the proposed omnidirectional method paves the way for X-ray scattering tensor tomography for the inspection of biomedical and material science samples (16, 36).

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of Diamond Light Source Ltd. The authors are grateful to Tunhe Zhou for fruitful discussion and John Sutter for correcting the manuscript.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

Hard X-ray omnidirectional differential phase and dark-field imaging

Hard X-ray omnidirectional differential phase and dark-field imaging