- Altmetric

Photoemission electron microscopy and imaging X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy are today frequently used to obtain chemical and electronic states, chemical shifts, work function profiles within the fields of surface- and material sciences. Lately, because of recent technological advances, these tools have also been valuable within life sciences. In this study, we have investigated the power of photoemission electron microscopy and imaging X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy for visualization of human neutrophil granulocytes. These cells, commonly called neutrophils, are essential for our innate immune system. We hereby investigate the structure and morphology of neutrophils when adhered to gold and silicon surfaces. Energy-filtered imaging of single cells are acquired. The characteristic polymorphonuclear cellular nuclei divided into 2–5 lobes is visualized. Element-specific imaging is achieved based on O 1s, P 2p, C 1s, Si 2p, and N 1s core level spectra, delivering elemental distribution with submicrometer resolution, illustrating the strength of this type of cellular morphological studies.

Combined photoemission electron microscopy (PEEM) and imaging X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) can be used to obtain element-specific images with lateral resolution on the micro- and nanolevel. These techniques are today frequently used for surface characterization of both hard (material science, thin film physics, semiconductors, nanomaterials)1−5 and soft materials (polymer physic, organo-materials).6−9 These techniques may also have high potential for surface characterization within life sciences, where laterally resolved topographical, elemental, and chemical information including chemical shifts and work function contrast are of interest, and there is today an urgent need for new complementary sub-micrometer analytical imaging tools for addressing biological challenges. One such example where there are several yet unresolved questions to be answered is the process when neutrophils adhere on surfaces. Neutrophils are the most abundant white blood cell in the bloodstream and a predominant part of the innate immune system. They are quick responders to a microbial threat and among the first cells to be recruited to an infected tissue. Neutrophils circulate in the blood in large numbers, and because of their abundance, they can quickly migrate and accumulate at an infected site or a point of injury. At the infected site, the neutrophils have the capacity to phagocytose, release cytotoxic granular contents, produce reactive oxygen species, and form extracellular traps.10−12 Neutrophils are polymorphonuclear cells, which exhibit two distinct morphological characteristics, i.e., the multilobulated and condensed nucleus and their intracellular granules that contain specific loads of enzymes.13,14 One of the most important abilities of neutrophils is correlated to the activation process, i.e., to rapidly change shape and to be able to spread out to fight intruders. The process when neutrophils adhere on a foreign material is affected by the surface physical, chemical, and topographical properties.15−17 New valuable information may be obtained by detailed elemental characterization of cell-surface interaction processes and changes in cellular morphology during adhesion and spreading.

Today there are several advanced instrumental tools available for imaging of biological samples, each one with pros and cons. Commonly used techniques with pros and cons are listed in Figure S1. A combination of tools will deliver a more complete picture of the biological system in focus. Time of flight secondary ion mass spectrometry images and molecular depth profiles on cells are excellent examples, where cluster of ions are used as a tool to etch through biological samples.18−20 Careful sample preparation and increased understanding of the etching rates of biological material are of main importance. The invention of super-resolution techniques such as stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy was awarded the Nobel Prize in 2014.21 The technique is fluorophore based and technical advances will increase the feed through for large field of views and may elevate STED microscopy to a powerful method for future imaging in life sciences.22−24

In this work, PEEM and imaging XPS are used as label-free and element-specific advanced analytical tools to address biological problems on the cellular level. PEEM has lately been shown to bring insight into biological specimen based on work function mapping and to obtain electrochemical properties and topographical information.25−30 PEEM enables quick analysis of sub-micrometer-sized samples, an excellent tool for screening prior to imaging XPS. Imaging XPS is delivering element specific images on the sub-micrometer level, and with the possibility to receive information on elemental states/oxidation states.

Bringing in new tools that offer chemical imaging with information on the spatial distribution of elements and chemical composition will extend the possibilities for a better understanding of biological system at the cellular and subcellular level. When new tools are introduced, it is of main importance to do benchmarking by using tools established within the field.

In this study, we have reported surface characterization using a combined PEEM and imaging XPS instrument (NanoESCA) of neutrophils and their morphology when adhered to silicon and gold surfaces as well as cross-sectional images of the neutrophils by analyzing ultrathin (60 nm) cryo-prepared slices. The NanoESCA have been used to obtain energy-filtered PEEM images of low energetic secondary electrons with contrast information from both the topography and work function variations of the substrate and the neutrophils complemented with cross-sectional PEEM images of the cells. Cellular morphology is imaged and the characteristic multilobulated cell nucleus is clearly visualized, which enable us to identify both euchromatin and the more condensed heterochromatin using threshold mapping. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and fluorescence microscopy are frequently used imaging techniques in cell biology and the techniques are used in this study as a standard/reference for benchmarking the methodology.

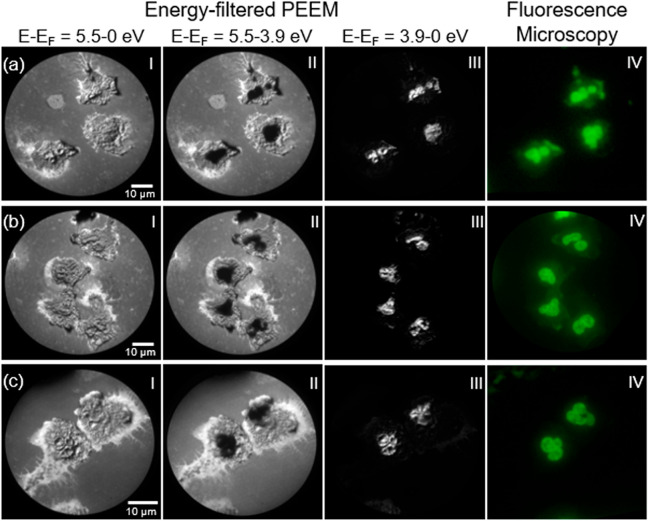

Inactivated neutrophils in the bloodstream are typically nonadherent and show a spherical-shaped morphology, and upon activation of, for example, a microbial threat (biomaterial/material), the neutrophils can flatten their shape with an enlarged surface and extended pseudopods.31 We have characterized attached neutrophils on both gold and silicon areas on a gold patterned silicon substrate using energy-filtered PEEM mode with a bright UV Hg arc light source (5.2 eV). A major benefit of using energy-filtered PEEM is the ability to acquire images over the photoemission threshold with work function contrasts. Threshold mapping of organic materials is strongly correlated to the thickness of the material on top of a conducting sample substrate. It is also correlated to the band structure of the organic material itself, where every organic material has its own band structure. We have analyzed the contrast changes for the attached neutrophils on the silicon part of the substrate at three areas (Figure 1a–c) with respect to work function and topographical information. On rough samples, the topographical contrast is due to the distortion of the electric field close to local structures. A contrast aperture is used to reduce parabolic trajectories of the electrons. PEEM images were acquired by scanning the kinetic energy over the threshold from E – EF = 5.5–0 eV. This enabled us to overlay individual energy-filtered PEEM images extracted from the threshold scan into three kinetic energy regions, (I) E – EF = 5.5–0 eV, (II) E – EF = 5.5–3.9 eV and (III) E – EF = 3.9–0 eV, shown in Figure 1 (I, II, III). Fluorescence microscopy have been used to capture images of the intracellular structures of the neutrophils. The nucleus has been stained using Sytox green, a commonly used fluorophore for labeling DNA, shown in Figure 1 (IV). The energy-filtered PEEM images of the neutrophils show a spread formation with extruded cell surface pseudopods and protrusions. Thin flexible tubulovesicular extensions of tubular and vesicular fragments are also visible. The polymorphonuclear morphology of the nucleus is clearly visualized with distinct lobulated segments, shown in Figure 1a. The possibility to use energy filtering with contrast from both work function variations and topography makes it possible to pinpoint and laterally resolve the entire nucleus showing the polymorphonuclear morphology for all the neutrophils (Figure 1 III).

(a–c) Sum of low energetic secondary electron energy-filtered PEEM images from a threshold scan at three different areas for neutrophils attached on a silicon substrate. (I) E – EF = 5.5–0 eV, (II) E – EF = 5.5–3.9 eV, and (III) E – EF = 3.9–0 eV. (IV) Fluorescence microscopy images of Sytox green stained DNA.

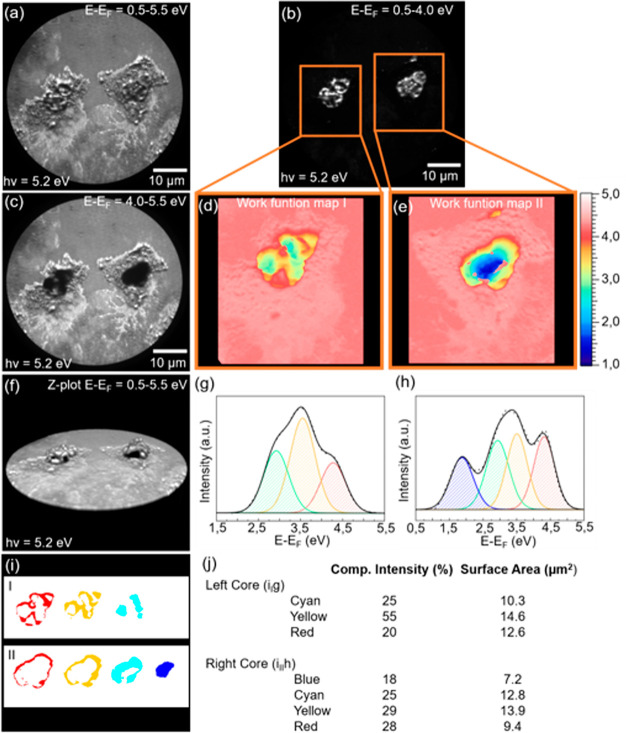

We have also created threshold maps to highlight the work function changes for two neutrophils throughout a threshold scan, shown in Figure 2. Three kinetic energy regions have been extracted from the entire scan over the threshold and overlaid into three images, E – EF = 0.5–5.5 eV (Figure 2a), E – EF = 0.5–4.0 eV (Figure 2b) and E – EF = 4.0–5.5 eV (Figure 2c). Two areas have been chosen for further threshold analysis and are marked with two boxes, shown in Figure 2b. We have also made a 3D rendering of the z-stack to further highlight the work function distribution (Figure 2f). A spectrum has been extracted for the nucleus of each individual neutrophil and has been deconvoluted using three and four peaks, shown in Figure 2g, h. These deconvoluted peaks are shown in blue, cyan, yellow, and red color and are assigned to kinetic energies of 1.9, 2.9, 3.5, and 4.3 eV, respectively. We have calculated the ratio of the individual peaks and the surface area for the corresponding component (Figure 2i,j). The deconvoluted peaks have a component intensity ratio of 30% cyan, 45% yellow, and 25% red with a surface area for the individual components of 10.3, 14.6, and 12.6 μm2, respectively. For the four deconvoluted peaks, the component intensity ratio is 18% blue, 25% cyan, 29% yellow, and 28% red. Their individual surface area is calculated as 7.2, 12.8, 13.9, and 9.4 μm2, respectively. PEEM analysis on biological samples such as neutrophils will introduce charging, and the work function is decreasing from the silicon substrate toward the cell nucleus. For the polymorphonuclear nucleus, the study of work function distribution shows distinct work function variations where the different lobules can be distinguished. The quantitative variation of the work function can be attributed to the adhesion process. The work function distribution image of the neutrophil presented in Figure 2d has a low work function component at 2.9 eV compared to the neutrophil in Figure 2e, which has a low work function component at 1.9 eV. This additional work function component indicates a thicker layer and a less spread out neutrophil.

Sum of low energetic secondary electron energy-filtered PEEM images from a threshold scan for two attached neutrophils on a silicon substrate. (a) E – EF = 0.5–5.5 eV, (b) E – EF = 0.5–4.0 eV and (c) E – EF = 4.0–5.5 eV. (d, e) Threshold generated maps showing the work function distribution from the marked area. (f) 3D rendering of a Z-stack showing the work function distribution from E – EF = 0.5–5.5 eV. (g, h) Extracted spectra from the core of the two attached neutrophils and deconvoluted using three and four peaks, respectively. (i) Individual components from the deconvoluted peaks and (j) component intensity and surface area.

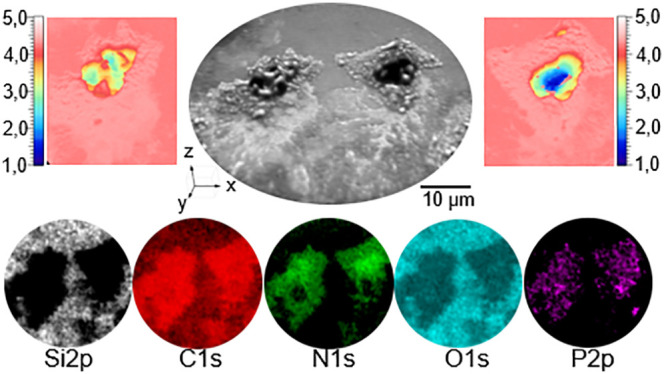

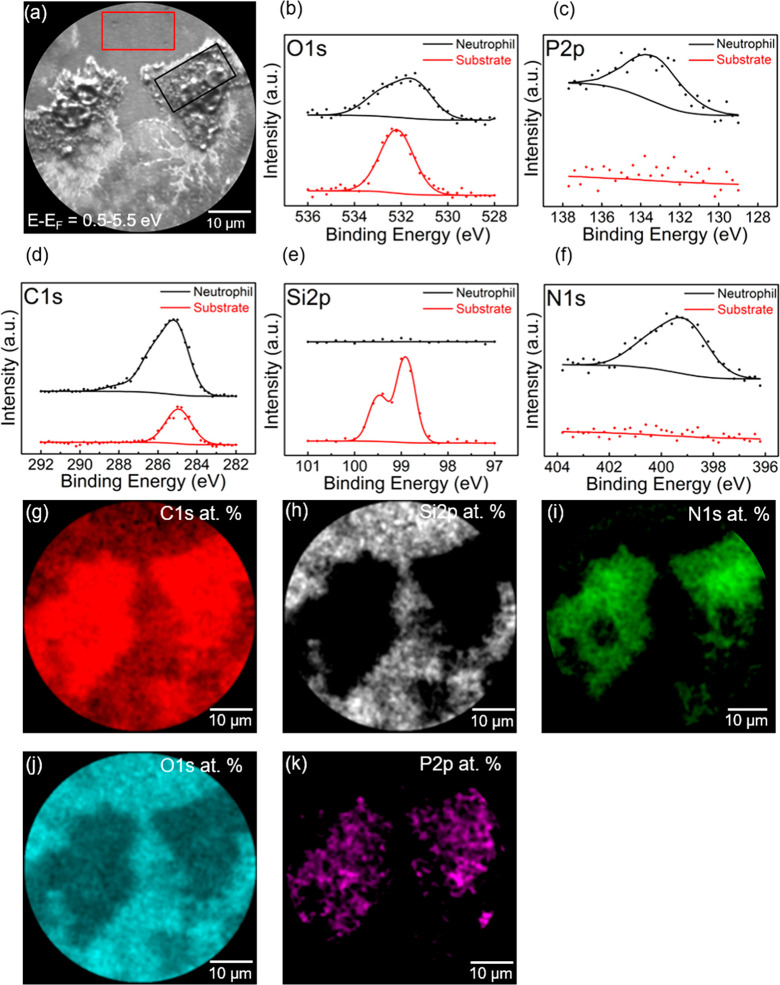

XPS elemental analysis and imaging XPS have been performed on the neutrophils shown in Figure 3. XPS core level spectra have been extracted from two areas marked in black (neutrophil) and red (substrate) for a comparison of the elemental distribution of a region over the neutrophil and the silicon substrate (Figure 3a). The extracted XPS spectra for the neutrophil showed presences of O, P, C, and N. For the silicon substrate, XPS showed presence of O, C and Si. A quantification of the element distribution for these two areas showed a relative concentration of O 1s (18.7%), P 2p (3.4%), C 1s (70.9%), and N 1s (7.0%) for the neutrophil and O 1s (39.6%), C 1s (36.7%), and Si 2p (23.7%) for the substrate. The XPS C 1s spectrum recorded from the substrate, clearly show a plain symmetric C 1s peak indicating presence of aliphatic carbon on top of the substrate, due to the fact that the substrate was exposed to the cell suspension during the sample preparation procedure. In the case of C 1s imaging XPS of the areas of the neutrophils, there is a strong increase in the total C 1s signal and a clear broadening of the C 1s peak on the higher binding energy side, compared to the C 1s peak recorded from the substrate. The line shape of the XPS C 1s spectrum indicates a complex chemical environment for carbon with several chemical states, i.e., the presence of C–N, C–O, C=O, corresponding to the presence of peptides and amine, hydroxyl, and carbonyl carboxylate carbon groups. This is in good agreement with the known complex structure of cells with a wide range of chemical states of cellular structures.32 This conclusion is also supported by the XPS P 2p and N 1s spectra in imaging mode for the same area. The presence of both N and P is in good agreement with presence of cellular components such as proteins, phospholipids, etc.33

Extracted XPS core level spectra from the two areas in (a) for neutrophil (black) and the substrate area respectively (red), (b) O 1s, (c) P 2p, (d) C 1s, (e) Si 2p and (f) N 1s. Imaging XPS of the atomic percent distribution of (g) C 1s, (h) Si 2p, (i) N 1s, (j) O 1s, and (k) P 2p core level electrons.

There is also a change of the line shape of XPS O 1s spectrum of the neutrophil compared to XPS O 1s for the substrate. This indicates a complex chemical structure consistent with the presence of neutrophils. The inelastic mean free path of electrons makes XPS a surface-sensitive technique. The Si 2p imaging XPS clearly show a strong signal from the substrate, but the signal is not detected from the areas where neutrophils are attached. The thickness of the cellular structures is based on the geometry used and the valid kinetic energies in the experimental setup and is estimated to be more than 100 Å.

XPS C 1s, Si 2p, N 1s, O 1s, and P 2p core level images have been acquired over the entire field of view (FoV) and are shown in Figure 3g–k, respectively.

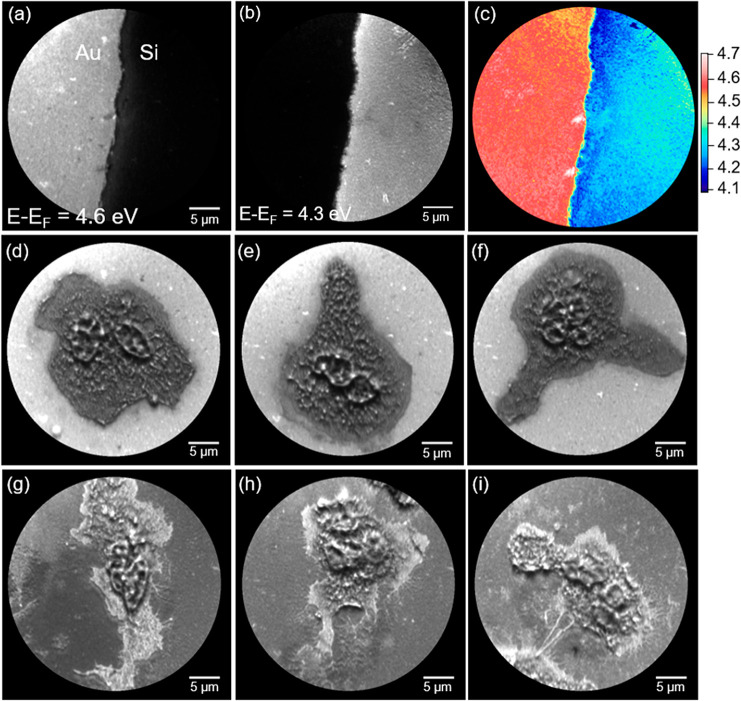

An energy-filtered PEEM comparison of attached neutrophils on silicon and gold have been done and is shown in Figure 4. The difference in work function between gold and silicon is demonstrated at the interface area between a part of the gold pattern and the silicon substrate.

Energy-filtered PEEM images of the interface between gold and silicon acquired at two kinetic energies, (a) E – EF = 4.6 eV and (b) E – EF = 4.3 eV, showing gold and silicon, respectively. (c) Threshold map showing the work function distribution. Sum of low energetic secondary electron energy-filtered PEEM images from E – EF = 5.5–2.0 eV for neutrophils attached on (d–f) gold and (g–i) silicon, respectively.

An energy-filtered threshold scan has been acquired by scanning the kinetic energy from E – EF = 5.5–2.0 eV. Two PEEM images have been extracted from the scan highlighting both the gold (Figure 4a) and the silicon (Figure 4b) area. The work function distribution in this FoV has been obtained and the gold and silicon work function values are homogeneously distributed throughout the PEEM image, with values of 4.6 and 4.3 eV, respectively (Figure 4c). The presence of aliphatic carbons on top of the polycrystalline gold surface reduces the value of the work function,34 here measured to be 4.6 eV, which is lower than for pure single-crystal gold surfaces (5.10–5.47 eV).35

There are earlier reports on difficulties measuring biological samples on high-work-function materials.36,37 In the present study, we visualize how the images are received with respect to contrast when using substrates of high-work-function materials such as gold compared to silicon substrates. Three neutrophils have been imaged on gold (Figure 4d–f) and silicon substrate (Figure 4g–i), respectively. It is clearly shown that imaging is achievable, and the essence of the structures is obtained for studies on both substrates. The polymorphonuclear morphology is clearly visualized and we do have indications that the fine structures at the edge of the neutrophils may be more easily obtained when the work function of the substrate is lower than that of the biological material of interest, consistent with earlier reports. For further details, see the pioneering work by Habliston et al.36 on DNA as a prototypical example delivering high-resolution images without the use of potentially harmful electron excitation.

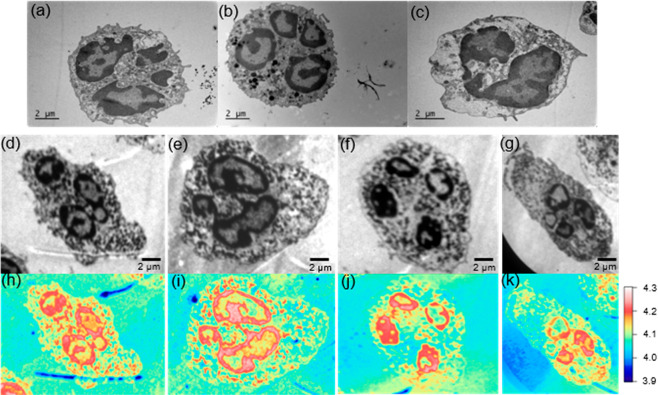

Thin sections of neutrophils have been prepared and characterized using TEM and energy-filtered PEEM, shown in Figure 5. Three neutrophils have been analyzed using TEM as a benchmarking technique, which is frequently used in cell biology. The sections for TEM and PEEM imaging are 60 nm thin; the thin sections were collected on Formvar-coated slot grids for TEM and directly deposited onto a silicon substrate for PEEM imaging. From the TEM analysis (Figure 5a–c), the neutrophils show distinct characteristics of the morphology. The polymorphonuclear morphology of the nucleus is clearly visualized with segregated lobules. There is a strong contrast of the nucleus with brighter and darker areas. These dark areas correspond to highly condensed heterochromatin, where the brighter contrast corresponds to euchromatin. Granules, which are vesicles specialized for containing specific loads of enzymes for bacterial killing, are also visible in the cytoplasm of the neutrophils.38,39 For PEEM imaging (Figure 5d–g) of the thin slices on silicon also shows a strong contrast of the shape and morphology of the neutrophils. A clear contrast in the nucleus between the brighter euchromatin and the darker heterochromatin is also visualized as compared to TEM. The distribution of the work function values are presented in work function maps (Figure 5h–k).

(a–c) TEM images of three neutrophils and (d–g) energy-filtered PEEM images of TEM prepared slices deposited on a silicon substrate with (h–k) corresponding work function maps.

To conclude, this work demonstrates element-specific, label-free imaging of cellular structures can be obtained using advanced photoemission microscopy and spectroscopy. PEEM and imaging XPS are used for chemical imaging, delivering information on the chemical composition and spatial distribution of elements for cellular structures and intracellular compartments in the sub-micrometer region. The morphology of activated neutrophils, both when adhered to plain gold and silicon surfaces and prepared as thin slices, are investigated. The characteristic polymorphonuclear morphology of the nucleus and enlarged neutrophil surface with extended pseudopods have been visualized by PEEM based on contrast from both topography and work function. We have also demonstrated work function variations in imaging mode for the cellular nucleus of the neutrophils. The tightly packed heterochromatin and the lightly packed euchromatin as well as granules were clearly visualized. Most importantly, element-specific imaging is obtained based on energy-filtered XPS O 1s, P 2p, C 1s, Si 2p, and N 1s, delivering elemental distribution with sub-micrometer resolution. Chemical shifts are also observed indicating several chemical states both for carbon and oxygen Fluorescence microscopy and TEM have been used as benchmarking techniques for comparison. The advanced tools of PEEM and imaging XPS have also potential for future studies of nanoparticle tracking and targeting in the submicrometer region.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03554.

Experimental section, commonly used surface analytical techniques with pros and cons, and a comparison of XPS C 1s spectra before and after X-ray exposure (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maria Ntzouni (Core Facility, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Linköping University, Sweden) for preparation of the thin slices and performing the TEM. The authors acknowledge financial support from the Swedish Government Strategic Research Area in Materials Science on Functional Materials at Linköping University (Faculty Grant SFO-Mat-LiU 2009-00971), grants from the Swedish Research Council VR (Grant 2019-02409), Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation KAW (2014.0276), CTS (CTS 18:399 19:379), and the Centre in Nanoscience and Nanotechnology at LiTH (CeNano) at Linköping University.

New Tools for Imaging Neutrophils: Work Function Mapping

and Element-Specific, Label-Free Imaging of Cellular Structures

New Tools for Imaging Neutrophils: Work Function Mapping

and Element-Specific, Label-Free Imaging of Cellular Structures