Edited by Bin Yu, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved January 13, 2021 (received for review August 5, 2020)

Author contributions: T.D., T.G., and A.I.J. designed research; T.D., T.G., and A.I.J. performed research; T.D. and A.I.J. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; T.D. and A.I.J. analyzed data; and T.D., T.G., and A.I.J. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

- Reliability Diagrams: Binning and Counting

- The CORP Approach: Optimal Binning via the PAV Algorithm

- Uncertainty Quantification

- CORP Score Decomposition: MCB, DSC, and UNC Components

- Discussion

- Appendix A: Simulation Settings

- Appendix B: Statistical Efficiency of CORP

- Appendix C: Properties of CORP Score Decomposition

- Supplementary Material

- Data Availability

Probabilistic classifiers assign predictive probabilities to binary events, such as rainfall tomorrow, a recession, or a personal health outcome. Such a system is reliable or calibrated if the predictive probabilities are matched by the observed frequencies. In practice, calibration is assessed graphically in reliability diagrams and quantified via the reliability component of mean scores. Extant approaches rely on binning and counting and have been hampered by ad hoc implementation decisions, a lack of reproducibility, and inefficiency. Here, we introduce the CORP approach, which uses the pool-adjacent-violators algorithm to generate optimally binned, reproducible, and provably statistically consistent reliability diagrams, along with a numerical measure of miscalibration based on a revisited score decomposition.

A probability forecast or probabilistic classifier is reliable or calibrated if the predicted probabilities are matched by ex post observed frequencies, as examined visually in reliability diagrams. The classical binning and counting approach to plotting reliability diagrams has been hampered by a lack of stability under unavoidable, ad hoc implementation decisions. Here, we introduce the CORP approach, which generates provably statistically consistent, optimally binned, and reproducible reliability diagrams in an automated way. CORP is based on nonparametric isotonic regression and implemented via the pool-adjacent-violators (PAV) algorithm—essentially, the CORP reliability diagram shows the graph of the PAV-(re)calibrated forecast probabilities. The CORP approach allows for uncertainty quantification via either resampling techniques or asymptotic theory, furnishes a numerical measure of miscalibration, and provides a CORP-based Brier-score decomposition that generalizes to any proper scoring rule. We anticipate that judicious uses of the PAV algorithm yield improved tools for diagnostics and inference for a very wide range of statistical and machine learning methods.

Calibration or reliability is a key requirement on any probability forecast or probabilistic classifier. In a nutshell, a probabilistic classifier assigns a predictive probability to a binary event. The classifier is calibrated or reliable if, when looking back at a series of extant forecasts, the conditional event frequencies match the predictive probabilities. For example, if we consider all cases with a predictive probability of about 0.80, the observed event frequency ought to be about 0.80 as well. While for many decades, researchers and practitioners have been checking calibration in myriads of applications (1, 2), the topic is subject to a surge of interest in machine learning (3), spurred by the recent recognition that “modern neural networks are uncalibrated, unlike those from a decade ago” (4).

Reliability Diagrams: Binning and Counting

The key diagnostic tool for checking calibration is the reliability diagram, which plots the observed event frequency against the predictive probability. In discrete settings, where there are only a few predictive probabilities, such as, e.g., , this is straightforward. However, even in discrete settings, there might be many such values. Furthermore, statistical and machine-learning approaches to binary classification generate continuous predictive probabilities that can take any value between zero and one, and typically the forecast values are pairwise distinct. In these settings, researchers have been using the “binning and counting” approach, which starts by selecting a certain, typically arbitrary, number of bins for the forecast values. Then, for each bin, one plots the respective conditional event frequency versus the midpoint or average forecast value in the bin. For calibrated or reliable forecasts, the two quantities ought to match, and so the points plotted ought to lie on, or close to, the diagonal (2, 5).

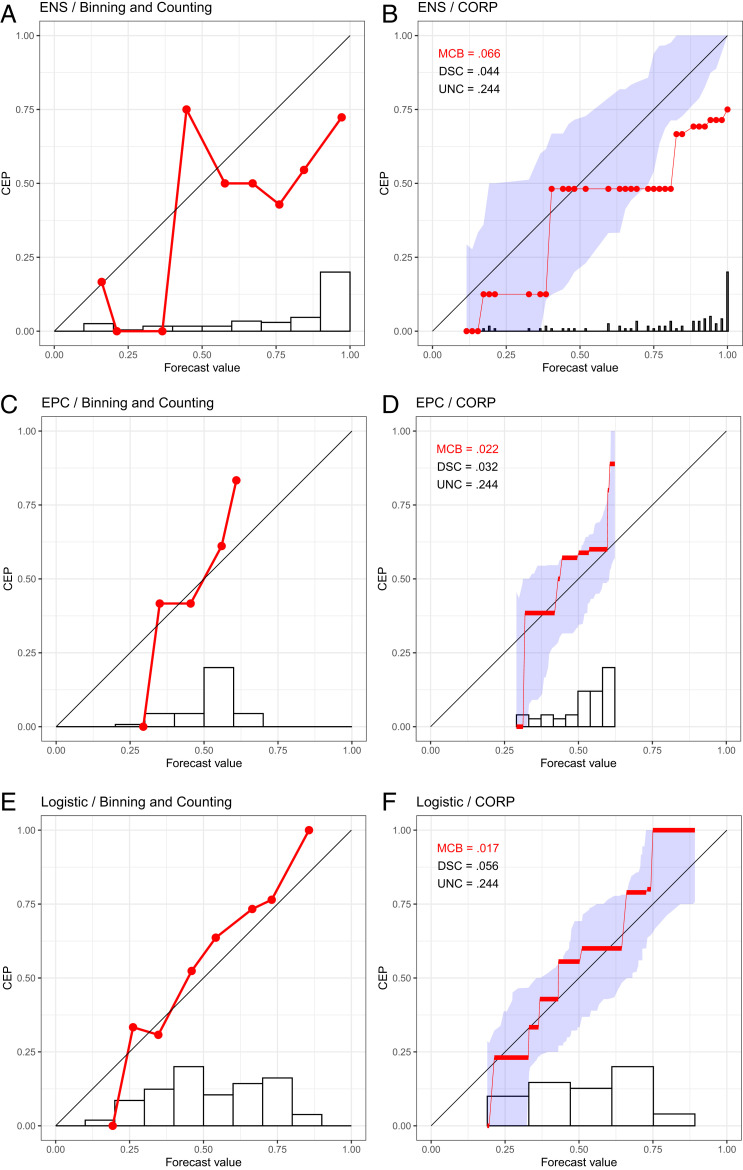

In Fig. 1 A, C and E, we show reliability diagrams based on the binning and counting approach with a choice of

Reliability diagrams for probability of precipitation forecasts over Niamey, Niger (7), in July–September 2016 under ENS (A and B), EPC (C and D), and Logistic (E and F) methods. (A, C, and E) We show reliability diagrams under the binning and counting approach with a choice of 10 equally spaced bins. (B, D, and F) We show CORP reliability diagrams with uncertainty quantification through 90% consistency bands. The histograms at the bottom illustrate the distribution of the

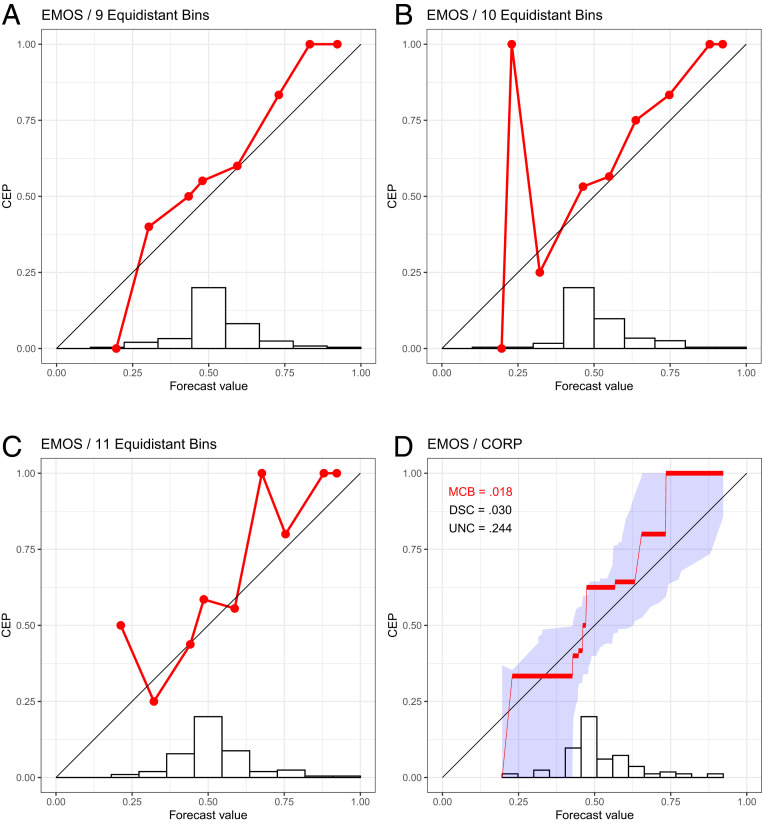

Reliability diagrams for probability of precipitation forecasts over Niamey, Niger (7), in July–September 2016 with the EMOS method, using the binning and counting approach with a choice of 9 (A), 10 (B), and 11 (C) equidistant bins, together with the CORP reliability diagram (D), for which we provide uncertainty quantification through 90% consistency bands.

Not surprisingly, the classical approach to plotting reliability diagrams is highly sensitive to the specification of the bins, and the visual appearance may change drastically under the slightest change. We show an example in Fig. 2 A–C for a fourth type of forecast at Niamey, namely, a statistically postprocessed version of the ENS forecast called ensemble model output statistics (EMOS), for which choices of

A simple and seemingly effective enhancement is to use evenly populated bins, as opposed to equidistantly spaced bins. Perhaps surprisingly, instability remains a major issue, typically caused by multiple occurrences of the same forecast value at bin breaks. Furthermore, the instabilities carry over to associated numerical measures of calibration, such as the Brier-score reliability component (10111213–14) and the Hosmer–Lemeshow statistic (15161718–19). These issues have been well documented in both research papers (16171819–20) and textbooks (2122–23) and may occur even when the size

While alternative methods for the choice of the binning have been proposed in the literature (5, 24, 25), extant approaches exhibit similar instabilities, lack theoretical justification, are elaborate, and have not been adopted by practitioners. Instead, researchers across disciplines continue to craft reliability diagrams and report associated measures of calibration based on ad hoc choices. In this light, Stephenson et al. (ref. 26, p. 757) call for the development of “nonparametric approaches for estimating the reliability curves (and hence the Brier score components), which also include[d] point-wise confidence intervals.”

Here, we introduce an approach to reliability diagrams and score decompositions, which resolves these issues in a theoretically optimal and readily implementable way, as illustrated on the forecasts at Niamey in Figs. 1 B, D, and F and 2D. In a nutshell, we use nonparametric isotonic regression and the pool-adjacent-violators (PAV) algorithm to estimate conditional event probabilities (CEPs), which yields a fully automated choice of bins that adapts to both discrete and continuous settings, without any need for tuning parameters or implementation decisions. We equip the diagram with quantitative measures of (mis)calibration (

Consistency.

The CORP reliability diagram and the

Optimality.

The CORP reliability diagram is optimally binned, in that no other choice of bins generates more skillful (re)calibrated forecasts, subject to regularization via isotonicity (ref. 30, theorem 1.10, and refs. 31 and 32).

Reproducibility.

The CORP approach does not require any tuning parameters or implementation decision, thus yielding well-defined and readily reproducible reliability diagrams and score decompositions.

PAV Algorithm-Based.

CORP is based on nonparametric isotonic regression and implemented via the PAV algorithm, a classical iterative procedure with linear complexity only (33, 34). Essentially, the CORP reliability diagram shows the graph of the PAV-(re)calibrated forecast probabilities.

In the remainder of the article, we provide the details of CORP reliability diagrams and score decompositions, and we substantiate the above claims via mathematical analysis and simulation experiments.

The CORP Approach: Optimal Binning via the PAV Algorithm

The basic idea of CORP is to use nonparametric isotonic regression to estimate a forecast’s CEPs as a monotonic, nondecreasing function of the original forecast values. Fortunately, in this simple setting, there is one, and only one, kind of nonparametric isotonic regression, for which the PAV algorithm provides a simple algorithmic solution (33, 34). To each original forecast value, the PAV algorithm assigns a (re)calibrated probability under the regularizing constraint of isotonicity, as illustrated in textbooks (ref. 35, figures 2.13 and 10.7), and this solution is optimal under a very broad class of loss functions (ref. 30, theorem 1.10). In particular, the PAV solution constitutes both the nonparametric isotonic least squares and the nonparametric isotonic maximum-likelihood estimate of the CEPs.

The CORP reliability diagram plots the PAV-calibrated probability versus the original forecast value, as illustrated on the Niamey data in Figs. 1 B, D, and F and 2D. The PAV algorithm assigns calibrated probabilities to the individual unique forecast values, and we interpolate linearly in between, to facilitate comparison with the diagonal that corresponds to perfect calibration. If a group of (one or more) forecast values are assigned identical PAV-calibrated probabilities, the CORP reliability diagram displays a horizontal segment. The horizontal sections can be interpreted as bins, and the respective PAV-calibrated probabilities are simply the bin-specific empirical event frequencies. For example, we see from Fig. 1B that the PAV algorithm assigns a calibrated probability of 0.125 to ENS forecast values between

The assumption of nondecreasing CEPs is natural, as decreasing estimates are counterintuitive, routinely being dismissed as artifacts by practitioners. Furthermore, the constraint provides an implicit regularization, serving to stabilize the estimate and counteract overfitting, despite the method being entirely nonparametric. Under the binning and counting approach, small or sparsely populated bins are subject to overfitting and large estimation uncertainty, as exemplified by the sharp upward spike in Fig. 2B. The assumption of isotonicity in CORP stabilizes the estimate and avoids artifacts; see the examples in Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S5.

In contrast to the binning and counting approach, which has not been subject to asymptotic analysis, CORP reliability diagrams are provably statistically consistent: If the predictive probabilities and event realizations are samples from a fixed, joint distribution, then the graph of the diagram converges to the respective population equivalent, as a direct consequence of existing large sample theory for nonparametric isotonic regression estimates (2728–29). Furthermore, CORP is asymptotically efficient, in the sense that its automated choice of binning results in an estimate that is as accurate as possible in the large sample limit. In Appendix B, we formalize these arguments and report on a simulation study, for which we give details in Appendix A, and which demonstrates that the efficiency of the CORP approach also holds in small samples.

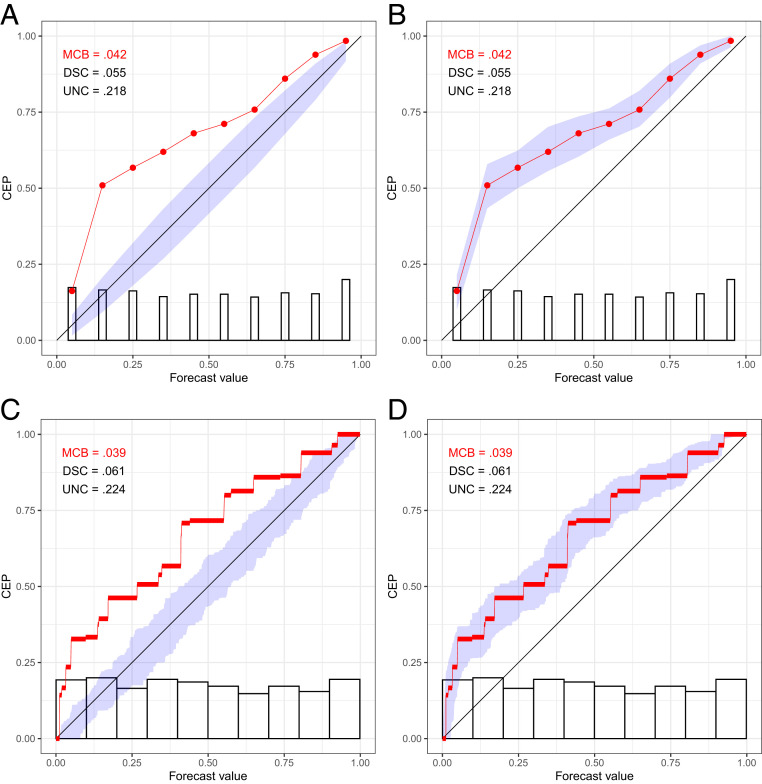

Traditionally, reliability diagrams have been accompanied by histograms or bar plots of the marginal distribution of the predictive probabilities, on either standard or logarithmic scales (e.g., ref. 36). Under the binning and counting approach, the histogram bins are typically the same as the reliability bins. In plotting CORP reliability diagrams, we distinguish discretely and continuously distributed classifiers or forecasts. Intuitively, the discrete case refers to forecast values that only take on a finite and sufficiently small number of distinct values. Then, we show the PAV-calibrated probabilities as dots, interpolate linearly in between, and visualize the marginal distribution of the forecast values in a bar diagram, as illustrated in Fig. 3 A and B. For continuously distributed forecasts, essentially every forecast takes on a different value, whence the choice of binning becomes crucial. The CORP reliability diagram displays the bin-wise constant PAV-calibrated probabilities in horizontal segments, which are linearly interpolated in between, and we use the Freedman–Diaconis rule (37) to generate a histogram estimate of the marginal density of the forecast values, as exemplified in Fig. 3 C and D. In our software implementation (38), a simple default is used: If the smallest distance between any two distinct forecast values is 0.01 or larger, we operate in the discrete setting, and else in the continuous one. The CORP reliability diagrams in Figs. 1–3 also display measures of (most importantly, and hence highlighted) (mis)calibration (

CORP reliability diagrams in the setting of discretely (A and B) and continuously (C and D), uniformly distributed, simulated predictive probabilities

Uncertainty Quantification

Bröcker and Smith (39) convincingly advocate the need for uncertainty quantification, so that structural deviations of the estimated CEP from the diagonal can be distinguished from deviations that merely reflect noise. They employ a resampling technique for the binning and counting method in order to find consistency bands under the assumption of calibration. For CORP, we extend this approach in two crucial ways, by generating either consistency or confidence bands and by using either a resampling technique or asymptotic distribution theory, where we leverage existing theory for nonparametric isotonic regression estimates (2728–29).

Consistency bands are generated under the assumption that the probability forecasts are calibrated, and so they are positioned around the diagonal. There is a close relation to the classical interpretation of statistical tests and P values: Under the hypothesized perfect calibration, how much do reliability diagrams vary, and how (un)likely is the outcome at hand? In contrast, confidence bands cluster around the CORP estimate and follow the classical interpretation of frequentist confidence intervals: If one repeats the experiment numerous times, the fraction of confidence intervals that contain the true CEP approaches the nominal level. The two methods are illustrated in Fig. 3, where the diagrams in Fig. 3 B and D feature confidence bands and in Fig. 3 A and C show consistency bands, as do the CORP reliability diagrams in Figs. 1 B, D, and F and 2D.

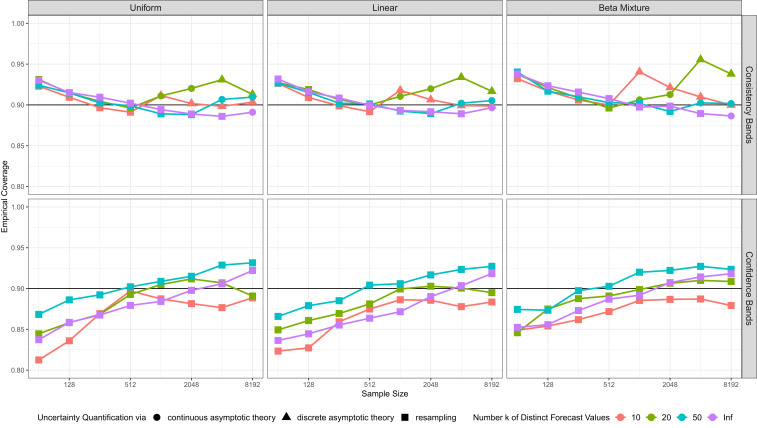

In our adaptation of the resampling approach, for each iteration, the resampled CORP reliability diagram is computed, and confidence or consistency bands are then specified by using resampling percentiles, in customary ways. For consistency bands, the resampling is based on the assumption of calibrated original forecast values, whereas PAV-calibrated probabilities are used to generate confidence bands. While resampling works well in small to medium samples, the use of asymptotic theory suits cases where the sample size

The distinction between discretely and continuously distributed forecasts becomes critical here, as the asymptotic theory differs between these cases. For discrete forecasts, results of El Barmi and Mukerjee (27) imply that the difference between the estimated and the true CEP, scaled by

In our software implementation (38), we use the following default choices. Suppose that the sample size is

Empirical coverage, averaged equally over the forecast values, of 90% uncertainty bands for CORP reliability diagrams under default choices for 1,000 simulation replicates. Upper concerns consistency bands, and Lower confidence bands. The columns correspond to three types of marginal distributions for the forecast values, and colors distinguish discrete and continuous settings, as described in Appendix A. Different symbols denote reliance of the bands on resampling, discrete, or continuous asymptotic distribution theory.

CORP Score Decomposition: MCB DSC UNC

Scoring rules provide a numerical measure of the quality of a classifier or forecast by assigning a score or penalty

| Score | Propriety | Analytic form of |

| Brier | Strict | |

| Logarithmic | Strict | |

| Misclassification error | Nonstrict |

Under any proper scoring rule, the mean score

Here, we adopt the general score decomposition introduced by Dawid (12), advocated forcefully by Siegert (14), and discussed by various other authors as well (e.g., refs. 13 and 43). Specifically, let

In the extant literature, it has been assumed implicitly or explicitly that the (re)calibrated and reference forecasts can be chosen at researchers’ discretion (e.g., refs. 14 and 45), without considering whether or not the transformed probabilities are calibrated in the classical technical sense. Specifically, a probability forecast with unique forecast values

We refer to the resulting decomposition as the CORP score decomposition, which enjoys the following properties:

∙

∙

∙The decomposition is exact.

In particular, the CORP score decomposition never yields counterintuitive negative values of the components, contrary to choices in the extant literature. The cases of vanishing components (

If

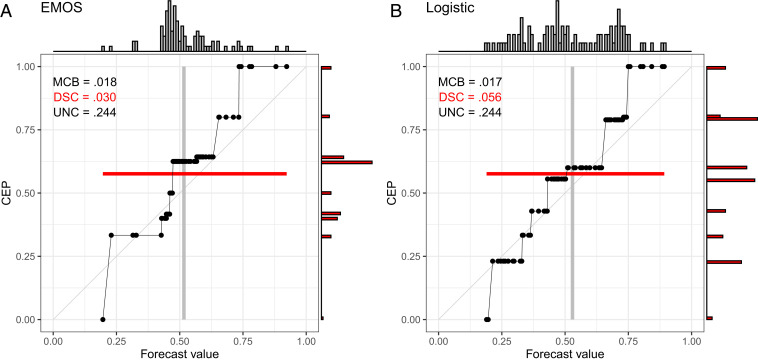

In Table 2, we illustrate the CORP Brier-score decomposition for the probability of precipitation forecasts at Niamey in Figs. 1 and 2. The purely data-driven Logistic forecast obtains the best (smallest) mean score, the best (smallest)

Interestingly, every proper scoring rule admits a representation as a mixture of elementary scoring rules (e.g., ref. 42, section 3.2). Consequently, the

Discussion

Our paper addresses two long-standing challenges in the evaluation of probabilistic classifiers by developing the CORP reliability diagram that enjoys theoretical guarantees, avoids artifacts, allows for uncertainty quantification, and yields a fully automated choice of the underlying binning, without any need for tuning parameters or implementation choices. The associated CORP decomposition disaggregates the mean score under any proper scoring rule into components that are guaranteed to be nonnegative.

Of particular relevance is the remarkable fact that CORP reliability diagrams feature optimality properties in both finite-sample and large-sample settings. Asymptotically, the PAV-(re)calibrated probabilities, which are plotted in a CORP reliability diagram, minimize estimation error, while in finite samples, PAV-calibrated probabilities are optimal in terms of any proper scoring rule, subject to the regularizing constraint of isotonicity.

While CORP reliability diagrams are intended to assess calibration, a variant—the CORP “discrimination diagram”—focuses attention at discrimination, by adding histograms for both the original and the PAV-recalibrated forecast probabilities, as detailed in SI Appendix, section S6. In Fig. 5, we show examples for the EMOS and Logistic forecasts from Figs. 1 and 2 and Table 2. While both forecasts are quite well calibrated, with nearly equal Brier-score

CORP discrimination diagrams for probability of precipitation forecasts over Niamey, Niger (7), in July–September 2016 with the EMOS (A) and Logistic (B) methods. The histograms at the top show the marginal distribution of the original forecast values, and the histograms at the right are for the PAV-recalibrated probabilities.

We believe that the proposals in this paper can serve as a blueprint for the development of novel diagnostic and inference tools for a very wide range of data-science methods. As noted, the popular Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for logistic regression is subject to the same types of ad hoc decisions on binning schemes, and hence the same types of instabilities as the binning and counting approach. Tests based on CORP and the

Perhaps surprisingly, the PAV algorithm and its appealing properties generalize from probabilistic classifiers to mean, quantile, and expectile assessments for real-valued outcomes (49). In this light, far-reaching generalizations of the CORP approach apply to binary regression in general, to standard (mean) regression, where they yield a mean squared error (MSE) decomposition with desirable properties, and to quantile and expectile regression. In all these settings, score decompositions have been studied (45, 50), and we contend that the PAV algorithm ought to be used to generate the (re)calibrated forecast in the general decomposition in Eq. 3, whereas the reference forecast ought to be the respective marginal, unconditional event frequency, mean, quantile, or expectile. We leave these extensions to future work and encourage further investigation from theoretical, methodological, and applied perspectives.

Appendix A: Simulation Settings

Here, we give details for the simulation scenarios in Figs. 4 and 6, where we use simple random samples with forecast values drawn from either Uniform, Linear, or Beta Mixture distributions, in either the continuous setting or discrete settings with

![MSE of the CEP estimates in CORP reliability diagrams for samples of size n, in comparison to the binning and counting approach with m=5, 10, or 50 fixed bins, or m(n)=[nα] quantile-based bins, where α=16, 13, or 12. Note the log–log scale. The simulation settings are described in Appendix A, and MSE values are averaged over 1,000 replicates.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765981191538-ebc75b4a-2963-431e-a9f7-595edf0f7b2a/assets/pnas.2016191118fig06.jpg)

MSE of the CEP estimates in CORP reliability diagrams for samples of size

We begin by describing the continuous setting, where the Uniform distribution has a uniform density and the Linear distribution a linearly increasing density with ordinate 0.40 at

Appendix B: Statistical Efficiency of CORP

Suppose that we are given a simple random sample

In the case of discretely distributed forecasts that attain a small number

Large-sample theory for the continuously distributed case is more involved and generally assumes that the CEP is differentiable with strictly positive derivative. Asymptotic results of Wright (28) for the variance and of Dai et al. (52) for the bias imply that the MSE of the CORP estimates decays like

The classical reliability diagram relies on a fixed number

In Fig. 6, we detail a comparison of CORP reliability diagrams to the binning and counting approach with either a fixed number

Appendix C: Properties of CORP Score Decomposition

Consider data

Theorem 1.

Given any set of original forecast values and associated binary events, suppose that we apply the PAV algorithm to generate a (re)calibrated forecast and use the marginal event frequency as reference forecast. Then, for every proper scoring rule

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)The decomposition is exact.

For further discussion see SI Appendix, section S5, where part A provides the proofs of Theorems 1 and 2, and part B illustrates that the properties 1–4 generally do not hold if recalibration methods other than isotonic regression are used. Dawid (12) introduced the score decomposition in Eq. 3 with the subtle, but important, difference that the recalibrated probabilities are obtained as the (unique) forecast-value-wise empirical event frequencies. Then, properties 1–5 of Theorem 1 are satisfied as well, and if the sequence of (unique) forecast-value-wise event frequencies is isotonic, Dawid’s decomposition and the CORP decomposition coincide. However, isotonicity is frequently violated, especially for datasets with many unique forecast values. Then, forecast-value-wise recalibration is prone to overfitting, and, as already noted by Dawid (12), smoothing methods are required to render the approach useable.

As before, let us assume that the unique forecast values

Theorem 2.

Under the Brier score, if the sequence

Acknowledgements

We thank two referees, Andreas Fink, Peter Knippertz, Benedikt Schulz, Peter Vogel, and seminar participants at the Luminy workshop on Mathematical Methods of Modern Statistics 2 and the virtual International Symposium on Forecasting 2020 for providing data, discussion, and encouragement. Our work has been supported by the Klaus Tschira Foundation, the University of Hohenheim and Heidelberg University, the Helmholtz Association, and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (German Research Foundation) Project ID 257899354 TRR 165.

Data Availability

The probability of precipitation forecast data at Niamey, Niger, are from the paper by Vogel et al. (ref. 7, figure 2), where the original data sources are acknowledged. Precipitation forecasts and realizations data have been deposited at GitHub (https://github.com/TimoDimi/replication DGJ20). Additional data analyses, simulation studies, technical discussion, and the proofs of Theorems 1 and 2 have been relegated to SI Appendix. Reproduction material for both the main article and SI Appendix, including data and code in the R software environment (51), are available online (38, 53). Open-source code for the implementation of the CORP approach in the R language and environment for statistical computing (51) is available on CRAN (38).

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Stable reliability diagrams for probabilistic classifiers

Stable reliability diagrams for probabilistic classifiers