Contributed by Yakir Aharonov, September 17, 2020 (sent for review January 14, 2020; reviewed by Lucien Hardy and Serge Massar)

Author contributions: Y.A., S.P., and D.R. designed research; Y.A., S.P., and D.R. performed research; and S.P. and D.R. wrote the paper.

Reviewers: L.H., Perimeter Institute; and S.M., Université Libre de Bruxelles.

- Altmetric

Conservation laws are one of the most important aspects of nature. As such, they have been intensively studied and extensively applied, and are considered to be perfectly well established. We, however, raise fundamental question about the very meaning of conservation laws in quantum mechanics. We argue that, although the standard way in which conservation laws are defined in quantum mechanics is perfectly valid as far as it goes, it misses essential features of nature and has to be revisited and extended.

We raise fundamental questions about the very meaning of conservation laws in quantum mechanics, and we argue that the standard way of defining conservation laws, while perfectly valid as far as it goes, misses essential features of nature and has to be revisited and extended.

Conservation laws, such as those for energy, momentum, and angular momentum, are among the most fundamental laws of nature. As such, they have been intensively studied and extensively applied. First discovered in classical Newtonian mechanics, they are at the core of all subsequent physical theories, nonrelativistic and relativistic, classical and quantum. Here, we present a paradoxical situation in which such quantities are seemingly not conserved. Our results raise fundamental questions about the very meaning of conservation laws in quantum mechanics, and we argue that the standard way of defining conservation laws, while perfectly valid as far as it goes, misses essential features of nature and has to be revisited and extended.

That paradoxical processes must arise in quantum mechanics in connection with conservation laws is to be expected. Indeed, on the one hand, physics is local: Causes and observable effects must be locally related, in the sense that no observations in a given space–time region can yield any information about events that take place outside its past light cone.* On the other hand, measurable dynamical quantities are identified with eigenvalues of operators, and their corresponding eigenfunctions are not, in general, localized. Energy, for example, is a property of an entire wave function. However, the law of conservation of energy is often applied to processes in which a system with an extended wave function interacts with a local probe. How can the local probe “see” an extended wave function? What determines the change in energy of the local probe? These questions lead us to uncover quantum processes that seem, paradoxically, not to conserve energy.

The present paper (which is based on a series of unpublished results, first described in refs. 3 and 4), presents the paradox and discusses various ways to think of conservation laws, but does not offer a resolution of the paradox.

Superoscillations

Essential to this paper is a mathematical structure we call “superoscillation.” Common wisdom assumes that no function can oscillate faster than its fastest Fourier component. Yet, as we show here, there is a large class of functions for which this assumption fails. Indeed, we have found functions that oscillate, on a given interval, arbitrarily faster than the fastest Fourier component. An example of such a function is the following:

Now, consider this function in the region

Note that there is no contradiction with the Fourier theorem, since the region where this function is (almost) identical to an oscillation of a frequency not contained by its Fourier decomposition does not extend over the entire region where the function is defined.

Although it is not essential for our present paper, it is interesting to note that outside the superoscillatory region,

The Experiment

The type of effect we describe here is common for all conserved quantities that depend on the shape of the wave function all over the space, including energy, momentum, and angular momentum. Here, we will focus on energy, for which the proof is more intuitive.

Here, we start by presenting the idea intuitively, in terms of a relativistic model, where the arguments are simpler. However, since relativistic quantum-field theory has well-known technical difficulties, we will in subsequent sections formulate a standard nonrelativistic quantum model and do all of the calculations there.

Consider a box of length

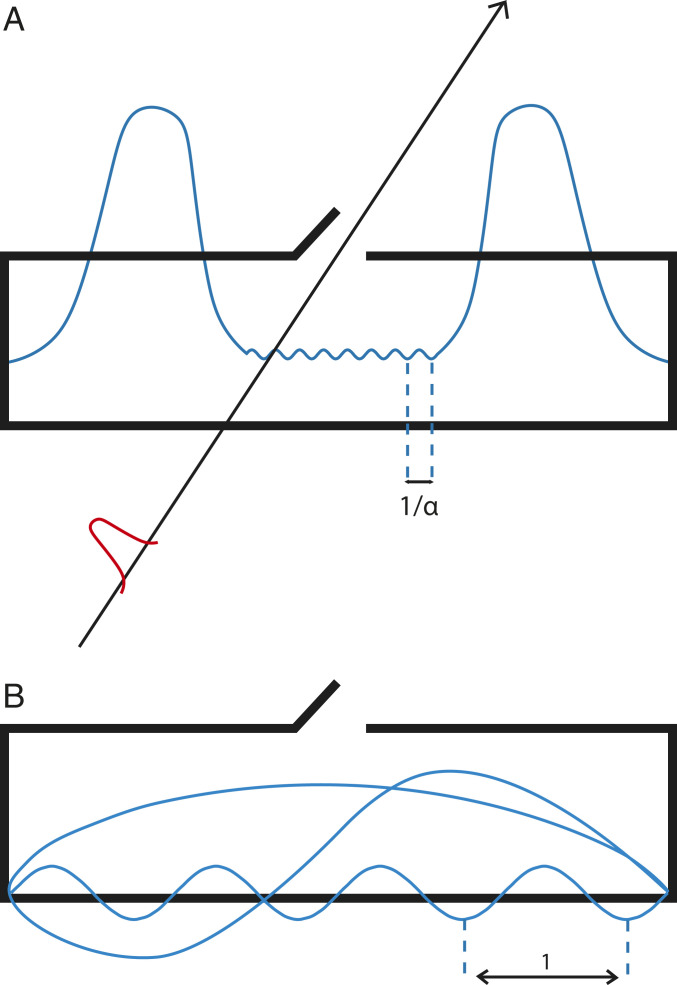

(A) A photon in the box in the specially prepared low-energy quantum state which, in the central region, oscillates with a spatial frequency greater than that of any Fourier components (B). As the opener is passing by, it opens the box and extracts the photon, if the photon is there. The shape of the wave function is not accurate, but simply illustrative; the true wave function is exponentially larger away from the center and has a more complicated shape.

From now on, however, for simplicity, we take

Given the relation between wavelength, frequency and energy for the photon, the decomposition 2 shows that the photon is in a superposition of different energy eigenstates with wave numbers

Suppose now that a mechanism that we will call the “opener” opens the box in the center and inserts a mirror, such that if the photon hits the mirror, it comes out of the box (as in Fig. 1). The mirror is left inside for a time

Let now the time

Naively, we would think that the emerging photon must have one of the energies

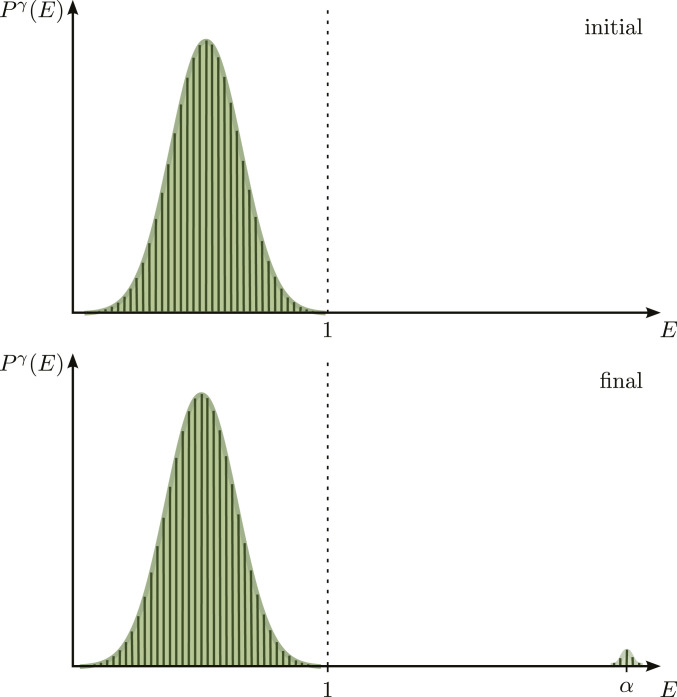

The initial and final distributions of the energy of the photon. Initially, it was a superposition of low energies and strictly no energy higher than one. Finally, a peak at energy

The initial and final probability distribution

To summarize, when the photon emerges from the box, it has much higher energy than it initially had. Where did the extra energy come from? This is the question that concerns us in this paper.

The Paradox

Inside the box, the photon was in a superposition of different energy eigenstates, all smaller than one, and out it emerges with the much higher energy

To put it differently, we can look at the total Hamiltonian, describing the photon and the opener. The total Hamiltonian is time-independent, since it describes the total system, with no parts left outside; the time dependence seen by the photon comes from the time evolution of the opener and its interaction with the photon. The total energy is conserved for time-independent Hamiltonians. Thus, we are tempted to say, all that happens is that the opener and the photon exchange energy: When the photon emerges from the box, and, as we proved, has higher energy than it had inside the box, the opener must have lost the same amount—a trivial case of energy exchange.

We now arrive at the crux of the problem. Although this explanation is the most natural, it is wrong: The photon could not have gotten its energy from the opener. The reason is again causality, as we shall now see.

Consider the case of a monochromatic high-energy photon of energy

Indeed, recall that the entire difference between the high-energy photon of energy

This is the paradox. The photon emerged from the box with energy much higher than it had inside, but the energy did not come from the opener, the only other system in the problem. Energy seems not to be conserved.

Energy Conservation

Faced with this paradox, one can respond in various ways. The conventional response is that there is no problem whatsoever, and there cannot ever be. In quantum mechanics, the standard formulation of a conservation law is that the probability distribution of the conserved variable over the entire ensemble should not change. This law applies to any time-independent Hamiltonian. On this basis, there should be absolutely no energy nonconservation in our example, either. And, of course, from this point of view, there is none. Indeed, in the preceding sections, we focused on what happens when the photon emerges from the box. But it is also possible (and actually far more probable) that the photon does not emerge from the box. It happens, because the wave function of the photon extends all over the box, so the photon has a nonzero (and, in fact, quite large) probability to be far from the central region. If so, it cannot reach the opening while the box is open; therefore, it cannot leave the box. To see standard energy conservation at work, we must consider these cases as well. What we find in these cases is that, again, the opener didn’t lose any energy (since it did not collide with the photon), but the photon remains in the box with lower energy (as the wave function loses its superoscillatory piece)—again, a paradox. Considering these cases as well, we find that, as expected, the probability distribution of the total energy (photon plus opener) did not change.

But—and this is the main point of our paper—we would like to argue that the standard formulation of conservation laws, though absolutely correct as far as it goes, is simply not enough. The standard conservation law is statistical and says nothing about individual cases. We would like to argue, however, that it is legitimate to ask what happened in a particular individual case. In our example, suppose we have in the box a photon of energy of order 1 eV (more precisely, a photon in a superposition of various energies, but absolutely none of them larger than 1 eV). Yet, when we open the box, the photon emerges with energy of order of 1 GeV. We should definitely be entitled to ask where the energy came from.

What we showed in our example is that this energy cannot come from the mechanism that extracts the photon from the box. Since this is the single other system in the problem, we are faced with energy nonconservation in this individual case. So we do have a problem that needs to be explained.

Furthermore, we also argue that the standard formulation is not only limited in that it cannot address individual cases, it is also unsatisfactory in the meaning of the story it tells.

Suppose that we repeat our experiment a large number of times. Consider a large number of boxes, each box containing just one single photon, prepared in the special low-energy state

Another possible response to the paradox is to argue that it makes no sense to talk about the energy of a photon as long as it is in a superposition of different energy eigenstates. However, we note that the photon had zero probability to have any energy larger than

As noted in the introduction, we do not offer any resolution here; we leave the paradox open. But below we provide more details. First, we present an explicit model; then, we analyze in more detail the standard energy conservation as applied to our situation. Although there are no contradictions here, the specific way in which the energy is conserved in the statistical ensemble is extremely unusual and instructive.

Explicit Model

We now give an explicit model. Since relativistic quantum-field theory has well-known technical difficulties, we will formulate a nonrelativistic model. The experiment is the same, the only difference being that, instead of a photon, the box contains a nonrelativistic particle. Of course, we are now no longer allowed to use relativistic causality arguments, and we will prove our statements by explicit calculations. Nevertheless, the intuition for the nonrelativistic model is exactly the same as in the relativistic case, since also nonrelativistic quantum mechanics allows finite time intervals in which a part of a wave function can act, to a good approximation, independently of the rest (8).

Consider the following Hamiltonian to model our experiment:

We let our particle have an internal degree of freedom, a “spin,” which determines whether the particle is in the box or free. The states

The opener’s free Hamiltonian is

The interaction term is designed to release the particle if it is situated in a window around the center of the box. This works as follows. The operator

Consider now that at time

To ensure that the opener opens the box during this time window, we choose its initial state

We now have to calculate the time evolution of the particle–opener system

To see the meaning of Eq. 11, we first note that, since the particle is now free, the energy eigenstates are the plane waves

One’s natural suspicion is that when the particle emerges from the box with energy

Note also that when the particle emerges with an energy slightly different from

The Standard Energy Conservation

As we discussed before, for any time-independent Hamiltonian, energy is always conserved in the standard sense—that is, the probability distribution of the total energy is time-independent. Since this is a theorem, it holds in our case as well; our paradox appears only at the level of individual cases. Yet, it is worth looking in more detail at the standard account of energy conservation as it applies in our case. As our case has interesting characteristics, the standard account of energy conservation turns out to be interesting as well.

The total Hamiltonian is

The total energy long before the interaction and long after it is simply the sum of the free energies,

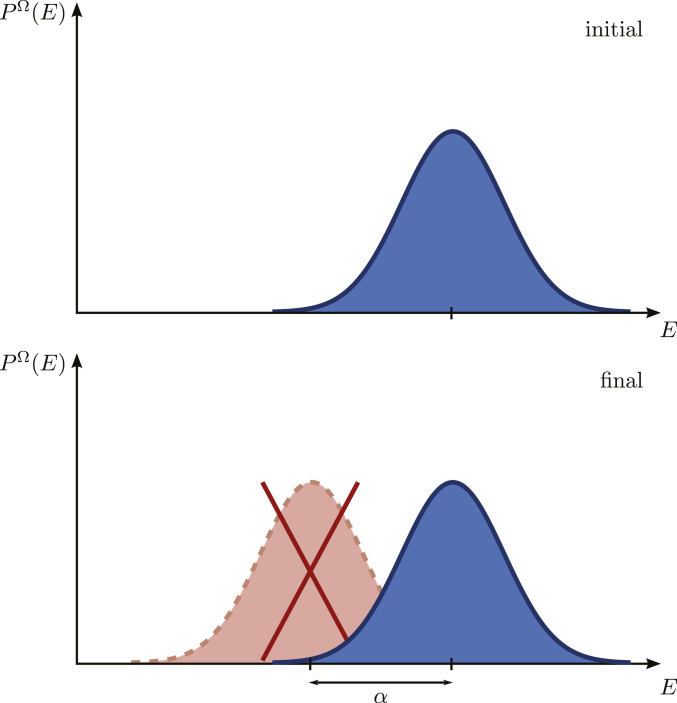

Before the interaction, there is no correlation between the energies of the particle and opener—i.e., the initial joint probability

All this leads to a surprising situation: The distribution of the energy of the particle changes without being accompanied by a corresponding change in the distribution of the energy of the opener, yet the distribution of the total energy is conserved.

Although the above situation is surprising, it is mathematically consistent, and it has remarkable implications. Denoting the conserved distributions

Eq. 21 can have a solution with

To understand the significance of the above results, we first note the general meaning of the Fourier transform of the energy distribution. Consider a particle prepared in the state

In our case, we want the opener–particle interaction to take place only for a finite time: The box must be opened, the mirror inserted, then extracted, and the box closed, all before information from remote places in the box can reach the opening. In our explicit model, the opener must, thus, move from far away, going from an initial state in which there is no interaction to an orthogonal state in which there is interaction, and then again to a state with no interaction. This is accomplished by moving through a long sequence of orthogonal states both before and after the interaction (as one can explicitly see in the model). Hence, since the interaction should only take a finite time

Note that the opener has the role of a catalyst: Its energy distribution doesn’t change, yet, without it, the particle’s energy distribution could not change, because the energy of the particle would then be the total energy, and changing its distribution would violate the standard energy-conservation law.

Modular Energy Exchange

It is interesting to examine further the changes in the energy distributions. Since neither the total energy distribution nor the opener energy distributions change, it is clear that the average energy of the particle cannot change: Indeed, both before the interaction and after

Furthermore, given that both initially and finally the energy distributions of the opener and particle are uncorrelated, and that the distributions of total energy and opener energy do not change, one can easily derive the fact that all of the moments of the particle energy distribution

We thus arrive at another remarkable conclusion: The energy distribution of the particle changes, although none of its moments change.

At first, it seems that something must be wrong—indeed, it is generally assumed that the moments of a distribution completely define it. This, however, is not so. It is actually perfectly possible for a distribution to change without any of its moments changing. In fact, in quantum mechanics, this behavior characterizes some of the most basic phenomena [such as momentum conservation in the two-slit experiment (9101112–13)]; and many of the “mysteries” of quantum mechanics have this mathematical effect at their core. This behavior generally stems from deep reasons connected with causality and nonlocality—as our present example illustrates.

So, if none of the moments of the particle’s energy distribution change, what changes? It is the average of observables that we call “modular energies” (11, 12), as we now show.

Consider the operator

Since

Note the interesting way in which the conservation of modular energy works. The total modular energy is conserved, so if one of two interacting systems changes its modular energy, this must be accompanied by changes in the modular energy of the other, yet the average modular energy of the particle (for some

In concluding this section, we would like to emphasize that the whole issue of exchange of modular energy (or momentum) without any (significant) exchange of any of its moments (or where the exchange of the moments plays a trivial role) is a general characteristic of phenomena in which a localized probe interacts with a system in an extended wave function. At the same time, the particular phenomena described in this paper (the high energy of the particle that emerges from the box) depend on the particular form 1 of the extended wave function. The possibility of exchange of modular energy without changes in any of the moments of the energy distribution simply opens a window of opportunity, through which the phenomena described here can manifest themselves. In other words, the exchange of modular energy without changes in the moments of the energy distribution is just a necessary, but not a sufficient, condition for the phenomena we describe here.

Discussion

To summarize, in our paper, we present an effect that raises questions about what we actually mean by conservation laws. The standard approach is statistical, and it is good as far as it goes. However, our effect begs the question of what happens in individual cases. A particle, prepared in a superposition of low-energy states and with no high-energy component whatsoever, comes out of a box with great energy. It is legitimate to ask where the energy comes from. We showed that the mechanism used for extracting the particle—the only other system in the problem—did not provide this energy, so we are left with a puzzle.

Our example concerned energy conservation. It is, however, clear that one can construct examples involving conservation of other quantities such as momentum or angular momentum (SI Appendix, section 5). The phenomenon is, therefore, a general one. Thus, we argue that the conservation laws of quantum mechanics must be revisited and extended. Without doing this, we will be missing a large part of the message that quantum mechanics is telling us.

Acknowledgements

Y.A. was supported by Israel Science Foundation Grant 1311/14 and also the Israeli Center of Research Excellence Excellence Center “Circle of Light” and the German–Israeli Project Cooperation. S.P. was supported by the Institute for Quantum Studies at Chapman University; European Research Council Advanced Grant Nonlocality in Space and Time; and the Institute for Theoretical Studies, ETH Zurich. D.R. was supported by John Templeton Foundation Project 43297 and Israel Science Foundation Grant 1190/13. The opinions expressed in this publication are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of the supporting foundations.

Data Availability.

There are no data underlying this work.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

On conservation laws in quantum mechanics

On conservation laws in quantum mechanics