Exploring effects of topology (23456–) in weakly correlated condensed-matter systems has led to the identification of fundamentally new quantum phases and phenomena, including the spin Hall effect (), protected transport of helical fermions (), topological superconductivity (), and large nonlinear optical response (, ). In the recently discovered Weyl semimetals, bulk three-dimensional (3D) Dirac cones describing massless relativistic quasiparticles are stabilized by breaking either inversion symmetry (IS) or time-reversal symmetry (TRS) (). Key experiments in their identification have been angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy (ARPES) (15–) as well as magnetotransport measurements, providing evidence for the chiral anomaly (, , )—charge pumping between a pair of Weyl nodes—via a large negative longitudinal magnetoresistance or, for nanostructures in high magnetic fields, Weyl orbits via quantum oscillation () or quantum Hall measurements ().Whereas the perturbative effect of correlations on topological electronic states is already under broad investigation (2223–), a completely open question is how strong correlations drive either related or entirely new topological states (262728–). To uncover them experimentally, not only new materials but also alternative measurement techniques have to be found. For instance, to characterize the recently proposed Weyl–Kondo semimetals (, ) neither of the canonical probes for weakly interacting Weyl semimetals seems suitable: ARPES experiments still lack the ultrahigh resolution needed to resolve strongly renormalized bands and magnetotransport signatures of the chiral anomaly or Weyl orbits are expected to be suppressed by the reduced quasiparticle velocities of strongly correlated materials (). Our discovery of a giant spontaneous Hall effect in one such material not only identifies an ideal technique but also demonstrates that strong correlations can drive extreme topological responses, which we expect to trigger much further work.

The material we have investigated is the noncentrosymmetric and nonsymmorphic heavy fermion semimetal () that has recently been identified as a candidate Weyl–Kondo semimetal (, ). Its low-temperature specific heat contains a giant electronic c=ΓT3 term that was attributed to electronic states with extremely flat linear dispersion (), corresponding to a quasiparticle velocity v⋆ that is renormalized by a factor of 103 with respect to the Fermi velocity of a simple metal (, ). This boosts the electronic ΓT3 term to the point that it even overshoots the Debye βT3 term of acoustic phonons (). To scrutinize this interpretation by other, more direct probes of topology is the motivation for the present work.

Results

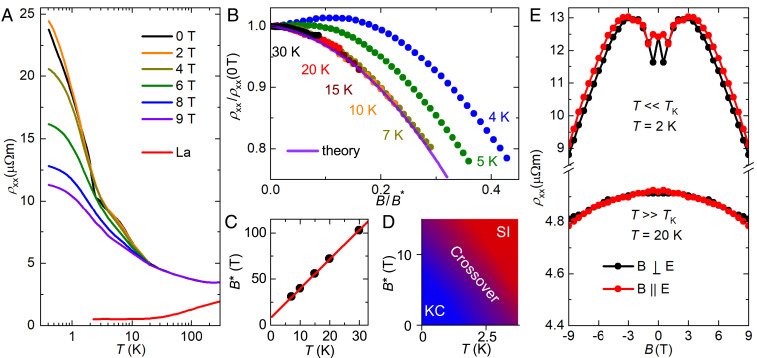

We start by showing that Ce3Bi4Pd3 is governed by the Kondo interaction and delineate the temperature and field range of Kondo coherence. The zero-field resistivity of Ce3Bi4Pd3 increases weakly with decreasing temperature, whereas the nonmagnetic reference compound La3Bi4Pd3 is metallic (Fig. 1A). This provides strong evidence that the semimetallic character of Ce3Bi4Pd3 is due to the Kondo interaction. Below the single-ion Kondo temperature TK=13 K, identified by associating the material’s temperature-dependent entropy with a spin 1/2 ground state doublet of the Ce 4f1 wavefunction split by the Kondo interaction (), a broad shoulder in the resistivity at about 7 K signals the cross-over to a Kondo coherent state (Fig. 1A). As shown in what follows, this is further supported by our magnetoresistance measurements (Fig. 1 B and C).

Fig. 1.

Electrical resistivity and magnetoresistance of Ce3Bi4Pd3. (A) Temperature-dependent electrical resistivity ρxx of Ce3Bi4Pd3 in various magnetic fields applied perpendicular to the electric field (B⊥E, transverse magnetoresistance) and of the nonmagnetic reference compound La3Bi4Pd3 in zero field (red). The feature in the 0 T data of Ce3Bi4Pd3 near 3 K is due to the onset of the spontaneous Hall effect (Fig. 2A), which leaves a finite imprint on ρxx because of the giant Hall angle (SI Appendix, section I H) and because of slight contact misalignment (SI Appendix, section I A). (B) Transverse magnetoresistance scaled to its zero-field value vs. scaled magnetic field B/B⋆, showing the collapses of data above 7 K onto the universal curve () (violet) expected for an S=1/2 Kondo impurity system in the incoherent regime and a breakdown of the scaling for temperatures below 7 K (shown here by using B⋆ from the linear fit in C—also, other choices of B⋆ cannot achieve scaling). (C) Scaling field B⋆, as determined in B, vs. temperature, showing a linear-in-T behavior as expected for a Kondo system in the single-impurity regime. Fitting B⋆=B0⋆(1+T/T⋆) to the data (red straight line) yields B0⋆=10 T and T⋆=2.5 K. (D) Temperature-field phase diagram displaying the single impurity (SI) and Kondo coherent (KC) regime as derived in C. (E) Transverse (black) and longitudinal (red, B‖E) magnetoresistance for temperatures well below (Top) and well above TK (Bottom). The data were symmetrized to remove any spurious Hall resistivity contribution and mirrored on the vertical axis for clarity.

Transverse magnetoresistance isotherms (Fig. 1B) in the incoherent regime between 7 and 30 K display the universal scaling typical of Kondo systems (, ): ρxx/ρxx(0 T) vs. B/B⋆ curves all collapse onto the theoretically predicted curve for an S=1/2 Kondo impurity system (), provided a suitable scaling field B⋆ is chosen. The resulting B⋆ is linear in temperature (Fig. 1C). Fitting B⋆=B0⋆(1+T/T⋆) to the data (red straight line) yields B0⋆=10 T and T⋆=2.5 K, which may be used as estimates of the field and temperature below which the system is fully Kondo coherent (blue area in Fig. 1D). Below 7 K, the scaling fails (Fig. 1B), as expected when crossing over from the incoherent to the Kondo coherent regime.

Before presenting our Hall effect results we show that, as anticipated, the chiral anomaly cannot be resolved in the Kondo coherent regime. We find that, at 2 K, the longitudinal and transverse magnetoresistance traces essentially collapse (Fig. 1E, Top). Because the amplitude ca of the chiral anomaly, being inversely proportional to the density of states (), is expected to scale as ca∝(v⋆)3, it is severely suppressed by the strong correlations. The fact that, also at high temperatures, we do not observe signatures of the chiral anomaly (Fig. 1E, Bottom) is consistent with our bandstructure calculations (to be presented later; see Fig. 4A), which reveal that the uncorrelated bandstructure contains Weyl nodes only far away (>100 meV) from the Fermi level.

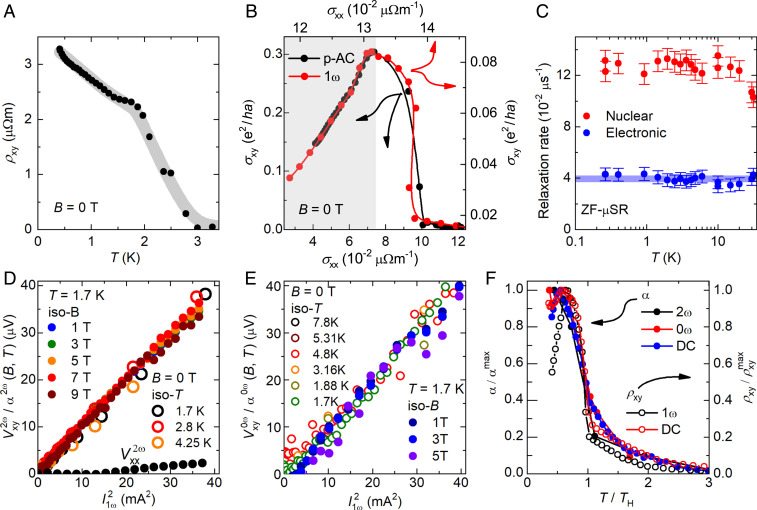

Our key observation, presented next, is a spontaneous (nonlinear, as will be discussed later) Hall effect which appears in Ce3Bi4Pd3 as full Kondo coherence is established below T⋆ (Fig. 2A). The corresponding spontaneous Hall conductivity σxy reaches a considerable fraction of the quantum of 3D conductivity (Fig. 2B). The experiment, using a pseudo-AC (alternating current) mode (Materials and Methods), was not only carried out in zero external magnetic field but also without any sample premagnetization process. Hall contact misalignment contributions were corrected for (SI Appendix, section I A and Figs. S1 and S2) and, thus, can also not account for the effect. Moreover, being in the Kondo coherent regime, the local moments should be fully screened by the conduction electrons. The resulting paramagnetic state is evidenced by the absence of phase transition anomalies in magnetization and specific heat measurements (SI Appendix, sections II B and C and Figs. S11 and S12), as well as by state-of-the-art zero-field (ZF) muon spin rotation (μSR) experiments. The latter reveal an extremely small electronic relaxation rate that is temperature-independent between 30 K and 250 mK (Fig. 2C; for two fully overlapping representative spectra, one well above and one well below T⋆, see SI Appendix, section II A and Fig. S10). This is unambiguous evidence that, in the investigated temperature range and in particular across T⋆, TRS is preserved in Ce3Bi4Pd3. In conjunction with the giant spontaneous Hall effect this observation is striking—we are not aware of any other 3D material with preserved TRS that has shown a spontaneous Hall effect.

Fig. 2.

Spontaneous Hall effect of Ce3Bi4Pd3. (A) Temperature-dependent direct current (DC) Hall resistivity ρxy in zero external magnetic field, showing a pronounced spontaneous Hall effect below 3 K. Data were taken without prior application of magnetic fields. (B) Spontaneous DC Hall conductivity σxy in units of the 3D conductivity quantum vs. longitudinal conductivity σxx, with temperature as implicit parameter, for the DC response of the sample in A (bottom and left axes, black) and for the 1ω response in an AC experiment on a sample from a different batch (top and right axes, red), both in zero magnetic field. In the Kondo coherent regime (gray shading), σxy is linear in σxx. (C) Temperature-dependent nuclear and electronic contributions to the muon spin relaxation rate obtained from ZF μSR measurements. The electronic contribution is extremely small and temperature-independent within the error bars, ruling out TRS breaking with state-of-the-art accuracy. Magnetization and specific heat measurements corroborate this finding (see SI Appendix, sections II B and C and Figs. S11 and S12. (D) Scaled 2ω spontaneous Hall voltage vs. square of 1ω driving electrical current in zero magnetic field for different temperatures and at 1.7 K for various magnetic fields. (E) Quantities analogous to D for the 0ω spontaneous Hall voltage. (F) Scaled coefficients of square-in-current response α2ω,0ω,DC from D and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S6, respectively (left axis) and linear-in-current response ρxy1ω,DC from B (right axis), as function of scaled temperature (TH is the onset temperature of the spontaneous Hall signal). The absolute values of αmax,i, ρxymax,i, and TH are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1.

We also measured the Hall effect in finite applied magnetic fields. We observe that the field-dependent Hall resistivity isotherms, ρxy(B), are fundamentally different below (Fig. 3A) and above T⋆ (Fig. 3B). Whereas above T⋆, ρxy shows simple linear-in-field behavior consistent with a single hole-like band, strong nonlinearities appear below T⋆. Most importantly, a large even-in-field component ρxyeven=[ρxy(B)+ρxy(−B)]/2 is observed (Fig. 3C) that even overwhelms the usual odd-in-field component ρxyodd=[ρxy(B)−ρxy(−B)]/2 (Fig. 3E). The nonlinear part of the latter, that scales with [ρxx−ρxx(4 K)]2 and is thus independent of the scattering time (Fig. 3F), is theoretically expected () and experimentally observed () in TRS broken Weyl semimetals, which is here realized by the finite magnetic field. The exciting discovery, however, is the even-in-B component, which is the finite-field extension of the spontaneous Hall effect. Both are incompatible with the standard (magnetic field or magnetization induced) Hall conductivity mechanism, where the elements σxy of the fully antisymmetric Hall conductivity tensor may couple only to a physical quantity G that breaks TRS (i.e., TG=−G, where T is the time-reversal operation) () and thus have to be an odd function of this quantity [e.g., σxy(B)=−σxy(−B), where G=B].

Fig. 3.

Hall resistivity of Ce3Bi4Pd3 in external magnetic fields. (A) In the Kondo coherent regime below T⋆ and B0⋆ (Fig. 1D), the magnetic field-dependent DC Hall resistivity ρxy(B) shows a pronounced anomalous Hall effect (AHE) and can be decomposed into an odd-in-B ρxyodd(B) (blue) and an even-in-B ρxyeven(B) (red) component. (B) Above T⋆, ρxy(B) is dominated by a linear-in-B normal Hall effect. (C) ρxyeven(B,T) is suppressed for T>T⋆ and B>B0⋆. (D) Scaled coefficients of the 2ω and 0ω Hall voltage in an AC experiment (from Fig. 2 D and F) as function of magnetic field. (E) Below T⋆ and B0⋆, ρxyodd(B,T) shows a pronounced AHE on top of a linear background from the normal Hall effect. (F) Amplitude of the odd-in-B AHE, estimated as the total odd-in-B component at 3.5 T (location of extremum) minus its value at 4 K, where the effect has disappeared (see E), vs. the square of the corresponding magnetoresistance difference [ρxx(T)−ρxx (4 K)] at 3.5 T, with T as implicit parameter. The observed quadratic dependence (red straight line) is in remarkable agreement with expectations for the AHE due to broken TRS as B is applied.

The question, then, is how to understand the Hall response beyond a broken TRS framework. Recent theoretical studies () show that in an IS breaking but TRS preserving material, a Hall current (density)

can be generated in a current-carrying state, as nonlinear response to an applied electric field

Ex. This field changes the equilibrium (Fermi–Dirac) distribution function

f0(k) into the nonequilibrium distribution function

f(k). In addition, in the presence of the Berry curvature

Ωzodd(k), that is odd in

k [i.e.,

Ωodd(k)=−Ωodd(−k)] for systems with broken IS (), it generates the anomalous velocity

vy. This state breaks TRS at the thermodynamic level, as

f(k) can be maintained only at the cost of entropy production (

S˙=jxEx). The Hall conductivity

σxy in is finite only under this condition, which is in contrast to a normal (linear-response) Hall conductivity (

SI Appendix, section I E).

Because σxy of is driven by this TRS invariant Berry curvature and not by an applied magnetic field, it does not need to be odd in B, and a finite σxy does not even require the presence of any B at all (thus the spontaneous Hall effect). In fact, the only influence the magnetic field has on this topological Hall effect is to successively reduce its magnitude with increasing field (Fig. 3D), similar to what happens when heating the material beyond T⋆ (Fig. 3C). The observations of a spontaneous Hall effect (Fig. 2) and an even-in-field Hall conductivity (Fig. 3) in Ce3Bi4Pd3 are smoking-gun evidence that the physical quantity underlying the phenomenon is not a magnetic order parameter (coupled linearly to B), as otherwise σxy would necessarily be an odd function in B. That the spontaneous Hall current is indeed associated with f(k) is further supported by the linear relationship between σxy and σxx in the Kondo coherent regime (Fig. 2B), consistent with a linear dependence on the scattering time (σxy∼τ) and thus the nonequilibrium nature of the effect. As recently emphasized (), this dependence sharply discriminates this effect from disorder-induced contributions.

Because according to the topological Hall current is determined by f(k), σxy will depend on Ex, and thus the Hall response jy=σxy(Ex)⋅Ex is expected to be nonlinear in Ex. By Taylor expanding f(k) around f0(k), a second harmonic response was derived (), which we have set out to probe by investigating both the dependence of the Hall response on the electric field (or current) strength and by analyzing the different components of the Hall response under AC and DC current drives (SI Appendix, section I D). As we will show in what follows, we do indeed observe this second harmonic response; in addition, however, we also detect terms that go beyond the prediction. The experiments as function of DC current drive reveal that the spontaneous Hall voltage VxyDC can be decomposed into a linear- and a quadratic-in-IDC contribution (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A, Right). This is in contrast to the longitudinal voltage VxxDC that is linear in current, representing an ohmic electrical resistivity (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A, Left). In our AC experiments, in response to an excitation at frequency ω we detect voltage contributions at 1ω, 2ω, and 0ω. Whereas Vxy1ω is linear in I1ω (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B), both Vxy2ω and the associated current rectified counterpart Vxy0ω (SI Appendix, Eq. S10) are quadratic in I1ω (Fig. 2 D and E). These three responses as well as the DC response described above appear simultaneously, as Kondo coherence develops with decreasing temperature (Fig. 2F) and must thus have a common origin.

Discussion

We start by discussing the terms Vxy2ω, Vxy0ω, and VxyDC∼I2. They can be understood within the perturbative treatment () of , where the spontaneous nonlinear Hall conductivity σxy is determined by the Berry curvature dipole Dxz as

For several noninteracting (and TRS-preserving) Weyl semimetals,

Dxz was computed by electronic bandstructure calculations (). The tangent of the Hall angle, defined as

tanΘH≡σxy/σxx, where

σxx is the normal (

1ω) longitudinal conductivity, was found to be at maximum (if the chemical potential is placed at the Weyl nodes) of the order

10−4 for a scattering time

τ=10 ps and an electric field of

Ex=102 V/m, corresponding to

tanΘH/Ex≤10−6 m/V (). An experimental confirmation of these predictions remains elusive to date. For

Ce3Bi4Pd3, we have measured

tanΘH/Ex values as large as

3×10−3 m/V in the second harmonic channel (

Fig. 2D). This giant value is even more surprising as it is obtained in a bulk semimetal, without any chemical potential tuning. Experimentally, such tuning is limited to the case of insulating (quasi) two-dimensional materials. Two comments are due. First, in gate-tuned bilayer () and few-layer ()

WTe2, which both feature a gap at the Fermi level,

2ω Hall voltages have recently been reported; they were attributed to a large—but not divergent—Berry curvature. We estimate the maximum values reached there to be

tanΘH≈5×10−3 and

10−4 and

tanΘH/Ex≈3×10−6 m/V and

10−8 m/V, respectively, thus again at least three orders of magnitude smaller than what we observe in

Ce3Bi4Pd3. Second, we point out that the above-discussed spontaneous nonlinear Hall effect is not to be confused with the AHE in TRS breaking Weyl semimetals () or the planar Hall effect in noncentrosymmetric Weyl semimetals (). In the former, the Berry curvature is related to a magnetization. In the latter, the amplitude of the effect is determined by that of the chiral anomaly (), which is strongly suppressed in Weyl–Kondo semimetals.

Next, we quantify the terms Vxy1ω and VxyDC∼I that have not been considered in the perturbative approach of ref (), though odd-in-current contributions can generally appear (SI Appendix, section I F). Intriguingly, these linear contributions show tanΘH values up to 0.5 (taken as the slope ∂σxy/∂σxx in Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Fig. S8B) and thus are even larger than the 2ω effect quantified above. Before describing how these new terms as well as the above-discussed spontaneous nonlinear Hall terms may naturally arise in a Weyl–Kondo semimetal picture, we show that other effects can be safely discarded.

Skew scattering, side jump, and multiband effects are investigated via the normal (antisymmetrized) Hall effect and magnetoresistance characteristics and shown to play negligible roles by quantitative analyses (SI Appendix, sections I B and C and Figs. S4 and S5). Spurious Hall contributions due to crystal anisotropies, which may arise in systems with lower than cubic symmetry, can also be ruled out (SI Appendix, section I G). Finally, the reproducibility of the spontaneous Hall effect over various samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S8) confirms the intrinsic nature of this phenomenon.

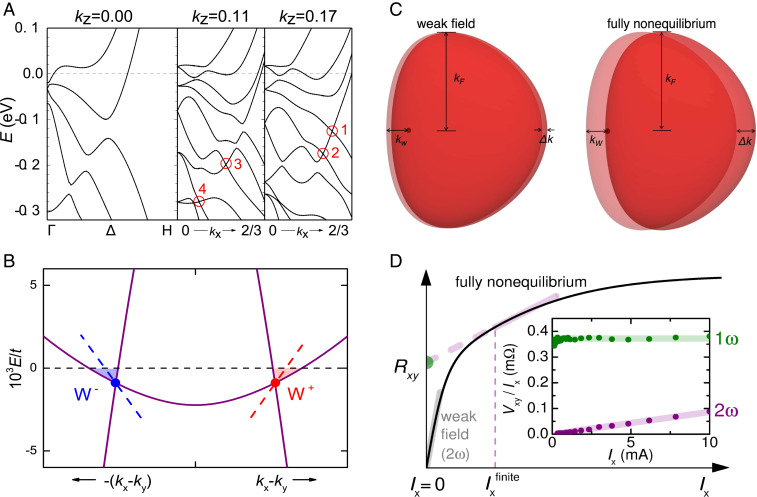

In a Weyl–Kondo semimetal, the Weyl nodes—where the Berry curvature is singular—are essentially pinned to the Fermi level (, ). The application of even small electric fields has a nonperturbative effect, in particular in the case of tilted Weyl cones (see SI Appendix, section IV C for an expanded discussion). A simple Taylor expansion of f(k) around f0(k), as done in ref. , will therefore fail to describe the effect. Quantitative predictions from fully nonequilibrium transport calculations based on an ab initio electronic bandstructure in the limit of strong Coulomb interaction and strong spin–orbit coupling are elusive to date. Thus, instead, we here present a conceptual understanding. While tilted Weyl cones are present already in the noninteracting bandstructure of Ce3Bi4Pd3 (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, section III), it is the Kondo interaction that drives emergent and highly renormalized Weyl nodes in the immediate vicinity of the Fermi level (Fig. 4B), as indicated by calculations for a periodic Anderson model () with tilted Weyl cones in the bare conduction electron band (SI Appendix, section IV and Fig. S13) and evidenced by thermodynamic measurements (). In the resulting tilted Weyl–Kondo semimetal, each Weyl node will be asymmetrically surrounded by a small Fermi pocket. The presence of such small pockets in Ce3Bi4Pd3 is supported by the small carrier concentration (8×1019

cm−3, or 0.002 charge carriers per atom) obtained from the normal Hall coefficient (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A). Due to the pinning of the Fermi energy to the Weyl nodes in a tilted Weyl–Kondo semimetal, the smallest distance between node and Fermi surface (kW, see Fig. 4C) can become extremely small. The application of even tiny electric fields will then induce shifts Δk in the distribution function f(k) that are sizable compared to kW (and possibly even compared to the Fermi wavevector kF), thus driving the system to a fully nonequilibrium regime (Fig. 4D). In this setting, a nonperturbative approach is needed and will allow for the appearance of terms beyond the second harmonic one predicted by Sodemann and Fu (), most notably the experimentally observed first harmonic one (SI Appendix, section I D). As the applied E field can then no longer be considered as a probing field, it introduces a directionality on top of the crystal’s space group symmetry and the selection rules, which hold in the perturbative regime, will be violated.

Fig. 4.

Theoretical description of Weyl–Kondo physics in Ce3Bi4Pd3. (A) Ab initio band structure of Ce3Bi4Pd3, with 4f electrons in the core. In the kx-kz plane, four different Weyl nodes (1–4) are identified; 1 and 4 are most strongly tilted (SI Appendix, section III). (B) Dispersion across a pair of Weyl (W+) and anti-Weyl (W−) nodes for a Weyl–Kondo model with tilted Weyl cones (SI Appendix, section IV). Energy is expressed in units of the conduction electron bandwidth t. The Kondo interaction pushes the Weyl nodes that are present in the bare conduction electron band far away from the Fermi energy, to the immediate vicinity of the Fermi level (here at E/t=0, slightly above the Weyl nodes). (C) Sketch of a Fermi pocket around the Weyl node W+ in B (dot) in zero electric field (light red) and its nonequilibrium counterpart with driving electric field (red), in the weak-field regime (left) and the fully nonequilibrium regime (right). (D) Sketch of the driving current-induced Hall resistance Rxy=Vxy/Ix, displaying the weak-field and fully nonequilibrium regimes. The Inset shows experimental results for Ce3Bi4Pd3, demonstrating the simultaneous presence of a spontaneous Hall signal in both the 2ω (Vxy∼Ix2) and 1ω (Vxy∼Ix) channel. The sum of both contributions corresponds to a linear-in-Ix Hall resistance with a finite offset (violet line with green dot in main panel), which is a characteristic of the fully nonequilibrium regime.

In conclusion, our Hall effect measurements unambiguously identify a giant Berry curvature contribution in a time-reversal invariant material, the noncentrosymmetric heavy fermion semimetal Ce3Bi4Pd3. The Hall angle per applied electric field, a figure of merit of the effect, is enhanced by orders of magnitude over values expected for weakly interacting systems, which we attribute to the effect of tilted and highly renormalized Weyl nodes that emerge very close to the Fermi surface out of the Kondo effect. The experiments reported here should allow for a ready identification of other strongly correlated nonmagnetic Weyl semimetals, be it in heavy fermion compounds or in other materials classes, thereby enabling much needed systematic studies of the interplay between strong correlations and topology. Our findings provide a window into the landscape of “extreme topological matter”—where strong correlations lead to extreme topological responses—that awaits systematic exploration. Finally, the discovered effect being present in a 3D material, in the absence of any magnetic fields and under only tiny driving electric fields, holds great promise for the development of robust topological quantum devices.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis.

Single crystals of Ce3Bi4Pd3 and the nonmagnetic reference compound La3Bi4Pd3 were synthesized using a Bi-flux method (). Their stoichiometry, phase purity, crystal structure, and single crystallinity were verified using powder X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX), and Laue diffraction. Because Ce3Bi4Pd3 is a stoichiometric compound in which all three elements have unique crystallographic sites, disorder is expected to be weak.

Measurement Setups.

Magnetotransport measurements were performed using various devices: two Quantum Design Physical Property Measurement Systems, in part with 3He or vertical rotator option, and an Oxford 4He flow cryostat using a Stanford Research SR830 lock-in amplifier. In the former, we used a pseudo-AC technique and in the latter a standard AC technique with lock-in detection. Electrical contacts for these measurements were made by spot-welding 12-μm-diameter gold wires to the samples in a five- or six-wire configuration, depending on the crystal size. Oriented single crystals were studied with the driving electrical current along different crystallographic directions (approximately along [103], [111], and [100]).

The μSR measurements were performed at the Dolly spectrometer of the Swiss Muon Source at Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen. The single crystals were aligned to form a mosaic with about 1-cm diameter and a thickness of about 0.5 mm, glued on top of a thin copper foil solidly clamped to a copper frame, thus optimally using the muon beam cross-section, minimizing the background from the sample holder, and guaranteeing good thermal contact. Combined with active vetoing, this setup resulted in very low spurious background signals. A cold-finger Oxford Heliox 3He system combined with a 4He Oxford Variox cryostat was used to reach temperatures down to 250 mK. By employing active compensation coils, true ZF conditions could be achieved during the ZF μSR experiments.

Ab Initio Calculations.

We performed non-spin-polarized band structure calculations for Ce3Bi4Pd4 based on density functional theory, treating the Ce 4f electrons in the open-core approximation and taking spin–orbit interaction into account. Weyl nodes in the kx–kz plane of the Brillouin zone were identified via their Berry curvature (see SI Appendix, section III for further details).

Model Calculations.

We extended the model for a Weyl–Kondo semimetal () to include beyond nearest-neighbor hopping terms and solved the self-consistent saddle-point equations for the strong interaction limit of the periodic Anderson model. We find a Weyl–Kondo solution with tilted Weyl cones. With the Kondo interaction placing the Fermi energy very close to the Weyl nodes, the Fermi surface comprises Fermi pockets that are asymmetrically distributed near the Weyl and anti-Weyl nodes. The Berry curvature, which diverges exactly at any Weyl or anti-Weyl node, is thus very large on the Fermi surface (see SI Appendix, section IV for further details).

![Hall resistivity of Ce3Bi4Pd3 in external magnetic fields. (A) In the Kondo coherent regime below T⋆ and B0⋆ (Fig. 1D), the magnetic field-dependent DC Hall resistivity ρxy(B) shows a pronounced anomalous Hall effect (AHE) and can be decomposed into an odd-in-B ρxyodd(B) (blue) and an even-in-B ρxyeven(B) (red) component. (B) Above T⋆, ρxy(B) is dominated by a linear-in-B normal Hall effect. (C) ρxyeven(B,T) is suppressed for T>T⋆ and B>B0⋆. (D) Scaled coefficients of the 2ω and 0ω Hall voltage in an AC experiment (from Fig. 2 D and F) as function of magnetic field. (E) Below T⋆ and B0⋆, ρxyodd(B,T) shows a pronounced AHE on top of a linear background from the normal Hall effect. (F) Amplitude of the odd-in-B AHE, estimated as the total odd-in-B component at 3.5 T (location of extremum) minus its value at 4 K, where the effect has disappeared (see E), vs. the square of the corresponding magnetoresistance difference [ρxx(T)−ρxx (4 K)] at 3.5 T, with T as implicit parameter. The observed quadratic dependence (red straight line) is in remarkable agreement with expectations for the AHE due to broken TRS as B is applied.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765980299381-6989d9be-538f-4374-9d5d-8ddde7e61e1c/assets/pnas.2013386118fig03.jpg)

Giant spontaneous Hall effect in a nonmagnetic Weyl–Kondo semimetal

Giant spontaneous Hall effect in a nonmagnetic Weyl–Kondo semimetal