Adaptive experimental designs can dramatically improve efficiency for particular objectives: maximizing welfare during the experiment (, ) or after it (, ); quickly identifying the best treatment arm (, ); maximizing the power of a particular hypothesis (8–); and so on. To achieve these efficiency gains, we adaptively choose assignments to resolve uncertainty about some aspects of the data-generating process, at the expense of learning little about others. For example, welfare-maximizing designs tend to focus on differentiating optimal and near-optimal treatments, collecting relatively little data about suboptimal ones.

However, once the experiment is over, we are often interested in using the adaptively collected data to answer a variety of questions, not all of them necessarily targeted by the design. For example, a company experimenting with many types of web ads may use a bandit algorithm to maximize click-through rates during an experiment, but still want to quantify the effectiveness of each ad. At this stage, fundamental tensions between the experiment objective and statistical inference become apparent: Extreme undersampling or nonconvergence of the assignment probabilities make reusing these data challenging.

In this paper, we propose a method for constructing frequentist CIs based on approximate normality, even when challenges of adaptivity are severe, provided that the treatment-assignment probabilities are known and satisfy certain conditions. To get a better sense of the challenges we face, we’ll first consider an example in which traditional approaches to statistical testing fail. Suppose we run a two-stage, two-arm trial as follows. For the first time periods, we randomize assignments with probability 50% for each arm. After T/2 time periods, we identify the arm with the higher sample mean, and for the next T/2 time periods, we allocate treatment to the seemingly better arm 90% of the time. Then, one estimator of the expected value Q(w) for each arm w∈{1, 2} is the sample mean at the end of the experiment,

where

Wt denotes the arm pulled in the

t-th time period and

Yt denotes the observed outcome. Both arms have the same outcome distribution:

Yt | Wt=w∼N0, 1 for all values of

t and

w.

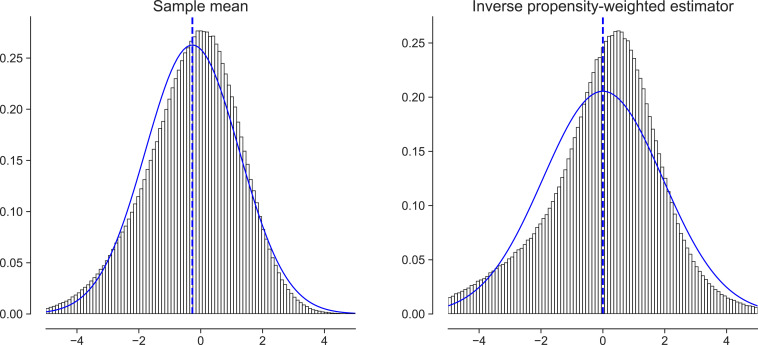

This example is relatively benign, in that adaptivity is minimal. Yet, as Fig. 1, Left shows, the estimate of the value of the first arm Q^AVG(1) is biased downward. This is a well-known phenomenon; see, e.g., refs. 1112131415–. The downward bias occurs because arms in which we observe random upward fluctuations initially will be sampled more, while arms in which we observe random downward fluctuations initially will be sampled less. The upward fluctuations are corrected as estimates of arms that are sampled more regress to their mean, while the downward ones may not be corrected because of the reduction in sampling. Here, we only show estimates for the first arm, so there are no selection-bias effects; the bias is a direct consequence of the adaptive data collection.

Fig. 1.

Distribution of the estimates Q^AVG(1) and Q^IPW(1) described in the introduction. The plots depict the distribution of the estimators for T=106, scaled by a factor T for visualization. The distributions are overlaid with the normal curve that matches the first two moments of the distribution, along with a dashed line that denotes the mean. All numbers are aggregated over 1 million replications.

One often-discussed fix to this particular bias problem is to use the inverse-probability weighting estimator, Q^IPW(w)=T−1∑t=1TIWt=wYt/et(w), where et(w) is the probability with which our adaptive experiment drew arm w in step t. This compensates for the outsize influence of early downward fluctuations that reduce the probability of an arm being assigned by up-weighting later observations within that arm when we see them. As seen in Fig. 1, Right, inverse-probability weighting fixes the bias problem, but results in a nonnormal asymptotic distribution. In fact, it can exacerbate the problem of inference: When the probability of assignment to the arm of interest tends to zero, the inverse probability weights increase, which, in turn, causes the tails of the distribution to become heavier.

If adaptivity essentially vanishes over the experiment, then we are justified in using naive estimators that ignore adaptivity. In particular, if assignment probabilities quickly converge to constants, then, in long-running experiments, we can often treat the data as if treatments had always been assigned according to these limiting probabilities; see, e.g., ref. or . It can be argued that most adaptive designs would eventually converge in this sense if run forever. However, how quickly they converge, and, therefore, the number of samples we’d need for adaptivity to be ignorable can vary considerably with the data-generating process. For example, we know that so long as some arm is best, an ϵ-greedy K-armed bandit algorithm will eventually assign to the best arm with probability 1−ϵ+ϵ/K and the others with probability ϵ/K; however, this happens only after the best arm is identified, which depends strongly on the unknown spacing between the arm values Q(1),…,Q(K). Moreover, in practice, adaptive experiments are often used precisely when there is limited budget for experimentation; therefore, substantial data collection after convergence is rare. As a result, if we try to exploit this convergence by using estimators that are only valid in convergent designs, we get brittle estimators. If we want an estimator that is reliable, we must use one that is valid, regardless of whether the assignment probabilities converge.

In this work, we propose a test statistic that is asymptotically unbiased and normal, even when assignment probabilities converge to zero or do not converge at all. We believe this approach to be of practical interest because normal CIs are widely used in several fields, including, e.g., medicine and economics. Moreover, though we focus on estimating the value of a prespecified policy, our estimates can also be used as input to procedures for testing adaptive hypotheses, which have as their starting point a vector of normal estimates (e.g., ref. ).

Other approaches to inference with adaptively collected data are available. One line of research eschews asymptotic normality in favor of developing finite-sample bounds using martingale concentration inequalities (e.g., refs. and , and references therein). Ref. considers approaches to debiasing value estimates using ideas from conditional inference (). And some avoid frequentist arguments altogether, preferring a purely Bayesian approach, although this can produce estimates that have poor frequentist properties (). Related Literature further reviews papers on policy evaluation.

Policy Evaluation with Adaptively Collected Data

We start by establishing some definitions. Each observation in our data is represented by a tuple (Wt,Yt). The random variables Wt∈W are called the arms, treatments, or interventions. Arms are categorical. The reward or outcome Yt represents the individual’s response to the treatment. The set of observations up to a certain time HT≔{(Ws,Ys)}s=1T is called a history. The treatment-assignment probabilities et(w)≔P[Wt=w |Ht−1], also called propensity scores, are time-varying and decided via some known algorithm, as it is the case with many popular bandit algorithms, such as Thompson sampling (, ).

We define causal effects using potential outcome notation (). We denote by Yt(w) the random variable representing the outcome that would be observed if individual t were assigned to a treatment w. In any given experiment, this individual can be assigned only one treatment, Wt, from a set of options W, so we observe only one realized outcome Yt=Yt(Wt). We focus on the “stationary” setting, where individuals, represented by a vector of potential outcomes (Yt(w))w∈W, are independent and identically distributed. However, the observed outcomes Yt are, in general, neither independent nor identically distributed, because the distribution of the treatment assignment Wt depends on the history of outcomes up to time t.

Given this setup, we are concerned with the problem of estimating and testing prespecified hypotheses about the value of an arm, denoted by Q(w)≔EYt(w) , as well as differences between two such values, denoted by Δ(w, w′)≔EYt(w) −EYt(w′) . We would like to do that even in data-poor situations, in which the data-collection mechanism did not target these estimands.

We will provide consistent and asymptotically normal test statistics for Q(w) and Δ(w, w′). This is done in three steps. First, we start with a class of scoring rules, which are transformations of the observed outcomes that can be used for unbiased arm evaluation, but whose sampling distribution can be nonnormal and heavy-tailed due to adaptivity. Second, we average these objects with carefully chosen data-adaptive weights, obtaining an estimator with controlled variance at the cost of some finite-sample small bias. Finally, by dividing these estimators by their SE, we obtain a test statistic that has a centered and standard normal limiting distribution.

Unbiased Scoring Rules.

A first step in developing methods for inference with adaptive data is to account for sampling bias. The following construction provides a generic way of doing so. We say that Γ^t(w) is an unbiased scoring rule for Q(w) if for all w∈W and t=1, …, T,

Given this definition, we can readily verify that a simple average of such a scoring rule,

is unbiased for

Q(w), even though the

Γ^t(w) are correlated over time, as the next proposition shows.

Proposition 1.

Let

Yt(w)w∈W

be an independent and identically distributed sequence of potential outcomes for

t=1, …, T, and let

Ht

denote the observation history up to time

t, as described above. Then, any estimator of the form [] based on an unbiased scoring rule [] satisfies

E[Q^T(w)]=Q(w).

One can easily verify Proposition 1 by applying the law of iterated expectations and [],

The key fact underlying this result is that the normalization factor

1/T used in [] is deterministic, and so cannot be correlated with stochastic fluctuations in the

Γ^t(w). In particular, we note that the basic averaging estimator [] is not of the form [] and, instead, has a random denominator

Tw—and is thus not covered by Proposition 1.

Given Proposition 1, we can readily construct several unbiased estimators for Q(w). One straightforward option is to use an inverse propensity score weighted (IPW) estimator:

This estimator is simple to implement, and one can directly check that the condition [] holds because, by construction,

PWt=w|Ht−1, Yt(w)=PWt=w|Ht−1=e(w;Ht−1).

The augmented inverse propensity weighted (AIPW) estimator generalizes this by incorporating regression adjustment ():

The symbol

m^t(w) denotes an estimator of the conditional mean function

m(w)=E[Yt(w)] based on the history

Ht−1, but it need not be a good one—it could be biased, or even inconsistent. The second term of

Γ^t AIPW(w) acts as a control variate: Adding it preserves unbiasedness, but can reduce variance, as it has mean zero conditional on

Ht−1 and, if

m^t(w) is a reasonable estimator of

m(w), is negatively correlated with the first term. When

m^t(w) is identically zero, the AIPW estimator reduces to the IPW estimator.

Asymptotically Normal Test Statistics.

The estimators discussed in the previous section are unbiased by construction, but, in general, they are not guaranteed to have an asymptotically normal sampling distribution. The reason for this failure of normality was illustrated in the example in the introduction for the IPW estimator. When, purely by chance, an arm has a higher sample mean in the first half of the experiment, it is sampled often in the second half, and the IPW estimator concentrates tightly. When the opposite happens, the arm is sampled less frequently, and the IPW estimator is more spread out. What we see in Fig. 1 is a heavy-tailed distribution corresponding to the mixture of the two behaviors. Qualitatively, what we need for normality is for the variability of the estimator to be deterministic. Formally, what is required is that the sum of conditional variances of each term in the sequence converges in ratio to the unconditional variance of the estimator (see e.g., ref. , theorem 3.5). Simple averages of unbiased scoring rules [] fail to satisfy this because, as we’ll elaborate below, the conditional variances of the terms in [] depend primarily on the behavior of the inverse assignment probabilities 1/et(w), which may diverge to infinity or fail to converge.

To address this difficulty, we consider a generalization of the AIPW estimator [] that nonuniformly averages the unbiased scores Γ^ AIPW using a sequence of evaluation weights

ht(w). The resulting estimator is the adaptively weighted AIPW estimator:

Evaluation weights

ht(w) provide an additional degree of flexibility in controlling the variance and tails of the sampling distribution. When chosen appropriately, these weights compensate for erratic trajectories of the assignment probabilities

et(w), stabilizing the variance of the estimator. With such weights, the adaptively weighted AIPW estimator [], when normalized by an estimate of its SD, has a centered and normal asymptotic distribution. Similar “self-normalization” schemes are often key to martingale central-limit theorems (see e.g., ref. .

Throughout, we will use evaluation weights ht(w) that are a function of the history Ht−1; we will call such functions history-adapted. Note that if we used weights with sum equal to one, we would have a generalization of the unbiased scoring property [], E[ht(w)Γ^t(w)∣Ht−1]=ht(w)Q(w), so the adaptively weighted estimator [] would be unbiased. In Constructing Adaptive Weights, we will discuss weight heuristics that do not sum to one, but that empirically seem to reduce variance and mean-squared error relative to alternatives. In that case, the estimator [] will have some bias due to the random denominator ∑t=1Tht(w). However, for the appropriate choices of evaluation weights ht(w) , this bias disappears asymptotically.

The main conditions required by our weighting scheme are stated below. Assumption 1 requires that the effective sample size after adaptive weighting—that is, the ratio (∑t=1TE[αt|Ht−1])2/E[∑t=1Tαt2] where αt≔ht(w)IWt=w/et(w)—goes to infinity. This implies that the estimator converges. Assumption 2 is the more subtle condition that unbiased estimators such as [] [i.e., estimators with ht(w)≡1] often fail to satisfy. Assumption 3 is a Lyapunov-type regularity condition on the weights controlling higher moments of the distribution.

Assumption 1 (Infinite Sampling).

The weights used in [] satisfy

Assumption 2 (Variance Convergence).

The weights used in []

satisfy,

for some

p>1,

Assumption 3 (Bounded Moments).

The weights used in []

satisfy,

for some

δ>0,

Theorem 2.

Suppose that we observe arms

Wt

and rewards

Yt=Yt(Wt),

and that the underlying potential outcomes

(Yt(w))w∈W

are independent and identically distributed with nonzero variance,

and satisfy

E|Yt(w)|2+δ<∞

for some

δ>0

and all

w.

Suppose that the assignment probabilities

et(w)

are strictly positive,

and let

m^t(w)

be any history-

adapted estimator of

Q(w)

that is bounded and that converges almost-

surely to some constant

m∞(w).

Let

ht(w)

be nonnegative,

history-

adapted weights satisfying Assumptions 1, 2, and 3.

Suppose that either

m^t(w)

is consistent or

et(w)

has a limit

e∞(w)∈[0, 1],

i.e.,

eitherThen,

for any arm

w∈W,

the adaptively weighted estimator []

is consistent for the arm value

Q(w),

and the following studentized statistic is asymptotically normal:

As Theorem 2 suggests, the asymptotic behavior of our estimator is largely determined by the behavior of the propensity scores

et(w) and evaluation weights

ht(w). If the former’s behavior is problematic, the latter can correct for that. For instance, the bounded-moments condition [] implies that when

et(w) decays very fast, the evaluation weights must also decay at an appropriate rate, so that the variance of the estimator does not explode. However, there are limits to what this approach can correct. For example, aggressive bandit procedures may assign some arms only finitely many times, and, in that case, it is impossible to estimate their values consistently. This scenario is ruled out by our infinite-sampling condition [], which would not be satisfied.

To build more intuition for the variance-convergence condition [], pretend for the moment that the evaluation weights ht(w) sum to one and that m^t(w) is consistent. Under these conditions, the variance of each AIPW score Γ^t(w) conditional on the past can be shown to be Var[Y1(w)]/et(w) plus asymptotically negligible terms, so the sum of conditional variances is asymptotically equivalent to Var[Y1(w)]∑t=1Tht2(w)/et(w). The variance-convergence condition [] says that this sum of conditional variances converges to its mean, which will be the unconditional variance of the estimator. If these simplifying assumptions really held, this argument would almost suffice to establish asymptotic normality, since variance-convergence conditions like this are nearly sufficient for martingale central-limit theorems (see, e.g., ref. , theorem 3.5).

When we use history-dependent weights ht(w) that do not sum to one, the normalized weights h~t≔ht(w)/∑s=1Ths(w) that scale our terms in [] are not a function of past data alone. However, the argument above provides valuable intuition in our proof, and Var[Y1(w)]∑t=1Th~t2/et(w) can be thought of as a reasonable proxy for the estimator’s variance. Minimizing this variance proxy suggests the use of weights ht(w)∝et(w). This heuristic, in combination with appropriate constraints, motivates an empirically successful weighting scheme that we’ll further discuss in Constructing Adaptive Weights.

If the weights ht(w) are not constructed appropriately, then ht2(w)/et(w) may behave erratically, and the variance-convergence condition will fail to hold. This can happen, for example, in a bandit experiment, in which there are multiple optimal arms, and uniform weights ht(w)≡1 are used. In this setting, the bandit algorithm may spuriously choose one arm at random early on and assign the vast majority of observations to it, so that no run of the experiment will look like an “average run,” and the ratio in [] will not converge. Or it may switch between arms infinitely often, in which case the ratio will converge only if it switches quickly enough that the random order is “forgotten” in the average. This issue persists even when assignment probabilities are guaranteed to stay above a strictly positive lower bound. In the next section, we will construct weights so that “variance-convergence” [] is guaranteed to be satisfied not only asymptotically, but for all sample sizes T.

The simplifying assumption that m^t(w) is consistent is not necessary: As stated in [], a variant of the argument above still goes through if the propensity score et(w) converges. In a nonadaptive experiment, the AIPW estimator will have optimal asymptotic variance if m^t(w) is consistent; if it is not, the excess asymptotic variance is a function of limt→∞et(w) and limt→∞m^t(w)−Q(w).

Constructing Adaptive Weights.

A natural question is how to choose evaluation weights ht(w) for which the adaptively weighted AIPW estimator [] is asymptotically unbiased and normal with low variance, i.e., for which we get narrow and approximately valid CIs. To this end, we’ll start by focusing on the variance-convergence condition []. Once we have a recipe for building weights that satisfy it, we’ll consider how to satisfy the other conditions of Theorem 2 and how to optimize for power.

The variance-convergence condition [] requires the sum ∑t=1Tht2/et to concentrate around its expectation. A direct way to ensure this is to make the sum deterministic. To do this, we choose weights via a recursively defined “stick-breaking” procedure,

where

λt satisfies

0≤λt<1 for all

1≤t≤T−1, and

λT=1. Because

λT=1, the definition above for

t=T directly implies that

∑t=1Tht2/et=1. This ensures that the variance-convergence condition [] is satisfied, so we call these

variance-stabilizing weights.

We call the function λt an allocation rate because it qualitatively captures the fraction of our remaining variance that we allocate to the upcoming observation. This is a useful class to consider because the analyst has substantial freedom in constructing weights by choosing different allocation rates λt, while ensuring that the resulting evaluation weights automatically satisfy the variance-convergence assumption, and satisfy other assumptions of Theorem 2 with some generality.

Theorem 3.

In the setting of Theorem 2, suppose that the treatment propensities satisfy

for

α∈[0,1)

and any positive constant

C.

Then,

the variance-

stabilizing weights []

defined by a history-

adapted allocation rate

λt(w)

are history-

adapted and satisfy Assumptions 1, 2,

and 3

if

λt(w)<1

for

t<T,

λT(w)=1

and,

for a finite positive constant

C′,

The main requirement of Theorem 3 is [], a limit on the rate at which treatment-assignment propensities

et decay. In a bandit setting, this constraint requires that suboptimal arms be pulled more often than implied by rate-optimal algorithms (see e.g., ref. , chapter 15), but still allows for sublinear regret. Given this constraint, the allocation-rate bounds [] are weak enough to allow us to construct variance-reducing heuristics, like [] below.

Given these simple sufficient conditions for our asymptotic normality result (Theorem 2) when we use variance-stabilizing weights, it remains to choose a specific allocation rate λt. This next step is what will allow us to be able to provide valid estimates, even when the share of relevant data vanishes asymptotically. A simple choice of allocation rate is

Given this choice, we can solve [] in closed form and get

ht=et/T. Weights of this type were proposed by ref. for the purpose of estimating the expected value of nonunique optimal policies that possibly depend on observable covariates. We call this method the

constant-

allocation scheme, because the variance contribution of each observation is constant (since

ht2/et≡1/T for these weights).

The constant-allocation scheme guarantees the variance-convergence condition [] and ensures asymptotic normality of the test statistic [], but it does not result in a variance-optimal estimator. We propose an alternative scheme in which λt adapts to past data and reweights observations to better control the estimator’s variance. To get some intuition, recall from the discussion following Theorem 2 that the variance of Q^Th(w) essentially scales like ∑t(ht2/et) / (∑t=1Tht)2. This implies that, in the absence of any constraints on how we choose the weights, we would minimize variance by setting ht∝et; this can be accomplished by using the allocation rate λt=et/∑s=tTes. If we use these weights and set m^t≡0 in [], the result is an estimator that differs from the sample average [] only in that it replaces the normalization 1/Tw with 1/∑t=1Tet. Our results do not apply to this choice of allocation rate λt because it depends on future treatment-assignment probabilities, and Theorem 3 requires that λt depend only on the history Ht−1.

However, this form of allocation rate suggests a natural heuristic choice of allocation rate:

where

E^t−1 denotes an estimate of the future behavior of the propensity scores using information up to the beginning of the current period. It can be estimated via Monte Carlo methods. A high-quality approximation is unnecessary for valid inference. All that is required is that the allocation-rate bounds [] be satisfied, although better approximations likely lead to better statistical efficiency.

In practice, the need to compute these estimates renders the construction [] unwieldy. Furthermore, the way the resulting weights depend on our model of the assignment mechanism is fairly opaque. As an alternative, we consider a simple heuristic that exhibits similar behavior and can be used when assignment probabilities are decided via Bayesian methods, such as Thompson sampling.

To derive our scheme, we consider two scenarios: one in which the assignment probabilities et are currently high and will continue being so in the future, as is the case when a bandit algorithm deems w to be an optimal arm; and a second scenario, in which the assignment probabilities will asymptotically decay toward zero as fast as the lower bound [] permits it to. If the first scenario is true, then we could approximate the behavior of [] by setting es=1 for all periods. If the second scenario is true, then we could do so by setting es=Cs−α for all periods. Letting A be an indicator that we are in the first scenario, we can consider a heuristic approximation to []:

Of course, we don’t know which scenario we are in. However, when assigning treatment via Thompson sampling,

et is the posterior probability at time

t that arm

w is optimal. This suggests the heuristic of averaging the two possibilities according to this posterior probability. Substituting, in addition, an integral approximation to

∑s=t+1Ts−α, we get the following allocation rate:

We call this the

two-point allocation scheme. Both the constant [] and two-point [] allocation schemes satisfy the allocation-rate bounds [] from Theorem 3; see

SI Appendix, section C.5.

Estimating Treatment Effects

Our discussion so far has focused on estimating the value Q(w) of a single arm w. In many applications, however, we may seek to provide inference for a wider variety of estimands, starting with treatment effects of the form Δ(w1, w2)=EYt(w1)−Yt(w2) . There are two natural ways to approach this problem in our framework. The first involves revisiting our discussion from Unbiased Scoring Rules, and directly defining unbiased scoring rules for Δ(w1, w2) that can then be used as the basis for an adaptively weighted estimator. The second is to reuse the value estimates derived above and set Δ^(w1, w2)=Q^(w1)−Q^(w2); the challenge then becomes how to provide uncertainty quantification for Δ^(w1, w2). We discuss both approaches below.

In the first approach, we use the difference in AIPW scores as the unbiased scoring rule for Δ(w1, w2).

One can then construct asymptotically normal estimates of

Δ(w1, w2) by adaptively weighting the scores

Γ^t(w1, w2) as in []. In

SI Appendix, section B, our main formal result allows for adaptively weighted estimation of general targets, such that both Theorem 2 and adaptively weighted estimation with scores [] are special cases of this result.

The second approach is conceptually straightforward; however, we still need to check that the estimator Δ^(w1, w2)=Q^(w1)−Q^(w2) can be used for asymptotically normal inference about Δ(w1, w2). Theorem 4 provides such a result, under a modified version of the conditions of Theorem 2, along with an extra assumption [].

Theorem 4.

In the setting of Theorem 2, let

w1, w2∈W

denote a pair of arms, and suppose that Assumptions 1, 2, and 3 are satisfied for both arms. In addition, suppose that the variance estimates defined in [] satisfy

and that for at least one

j∈{1,2},

eitherThen,

the vector of studentized statistics []

for

w1

and

w2

is asymptotically jointly normal with identity covariance matrix.

Moreover,

Δ^T(w1,w2)

below is a consistent estimator of

Δ(w1,w2)=EYt(w1)−Yt(w2) ,

and the following studentized statistic is asymptotically standard normal.

Both approaches to inference about

Δ(w1, w2) are of interest, and may be relevant in different settings. In our experiments, we focus on the estimator

Δ^(w1, w2)=Q^(w1)−Q^(w2) studied in Theorem 4, as we found it to have higher power—presumably because allowing separate weights

ht(w) for different arms gives us more control over the variance. However, adaptively weighted estimators following [] that directly target the difference

Δ(w1, w2) may also be of interest in some applications. In particular, they render an assumption like [] unnecessary and, following the line of argumentation in ref. , they may be more robust to nonstationarity of the distribution of the potential outcomes

Yt(w).

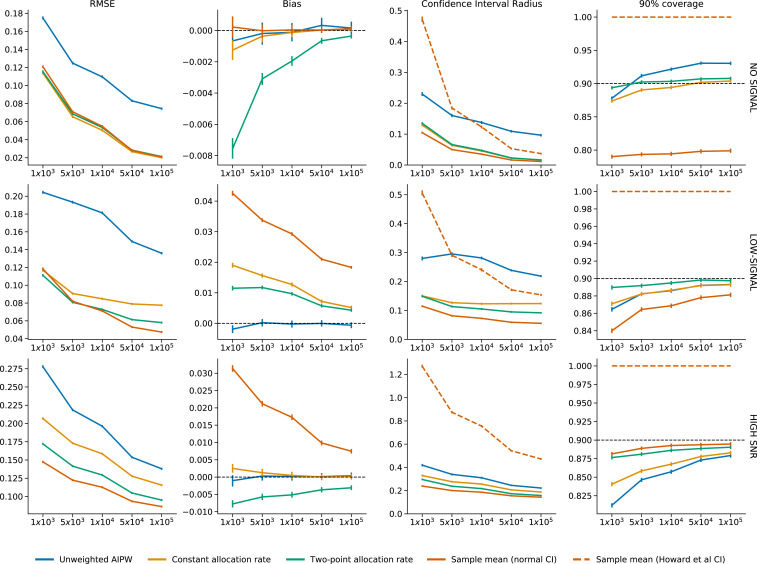

Numerical Experiments

We compare methods for estimating of arm values Q(w) and their differences Δ(w,w′), as well as constructing CIs around these estimates, under different data-generating processes.

We consider four point estimators of arm values Q(w): the sample mean [], the AIPW estimator [], and the adaptively weighted AIPW estimator [] with constant [] and two-point [] allocation rates. Around each of these estimators, we construct CIs Q^T±zα/2V^T1/2 based on the assumption of approximate normality. For the AIPW-based estimators, we use the sample mean of arm rewards up to period t−1 as the plug-in estimator m^t(w) and the estimate of the variance given in []. For the sample mean, we use the usual variance estimate V^AVG(w)≔Tw−2∑t:Wt=wT(Yt−Q^TAVG(w))2. Approximate normality is not theoretically justified for the unweighted AIPW estimator or for the sample mean. We also consider nonasymptotic CIs for the sample mean, based on the method of time-uniform confidence sequences described in ref. . See SI Appendix, section D.2 for details.

In addition, we consider four analogous estimators for the treatment effect Δ(w,w′): the difference in sample means, the difference in AIPW estimators [], and the adaptively weighted AIPW estimator [] with constant [] and two-point [] allocation rates. For the AIPW-based estimators, we use m^t(w) as above for the plug-in and the estimate of the variance given in []. For the sample mean, we use the usual variance estimate V^AVG(w)+V^AVG(w′). For the method based on ref. , we construct CIs for the treatment effect by using the union bound to combine intervals around each sample mean.

We have three simulation settings, each with K=3 arms, yielding rewards that are observed with additive uniform[−1,1] noise. The settings differ in the size of the gap between the arm values. In the no-signal case, we set arm values to Q(w)=1 for all w∈{1,2,3}; in the low-signal case, we set Q(w)=0.9+0.1w; and in the high-signal case, we set Q(w)=0.5+0.5w. During the experiment, treatment is assigned by a modified Thompson sampling method (see, e.g., ref. ): First, tentative assignment probabilities are computed via Thompson sampling with normal likelihood and normal prior; they are then adjusted to impose the lower bound et(w)≥(1/K)t−0.7. See SI Appendix, section D.2 for details.

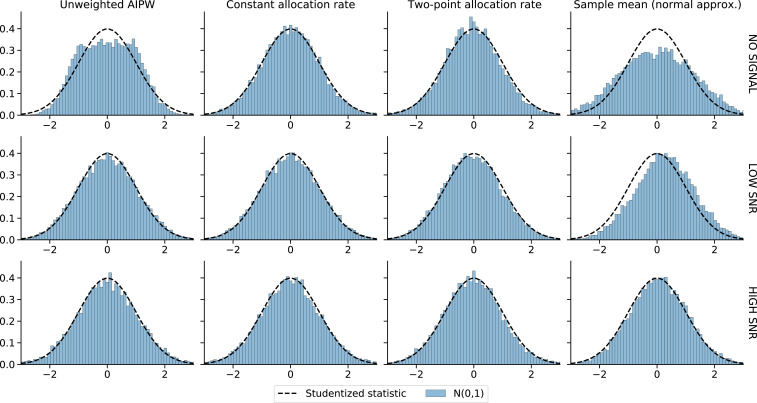

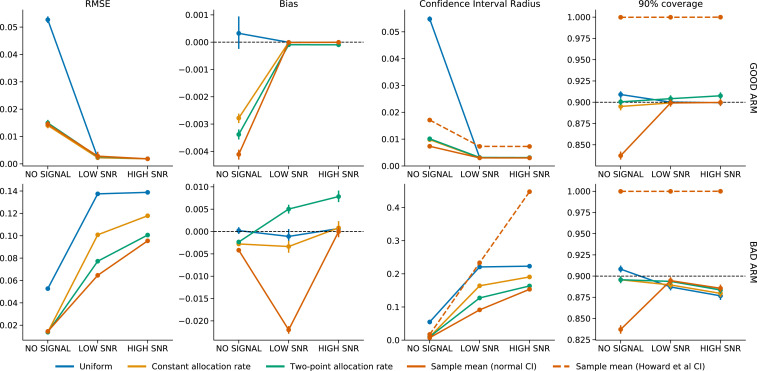

As a short mnemonic, in what follows, we call arms 1 and 3 the “bad” arm and “good” arm, respectively. As these labels are fixed, tests involving the value of the good arm are tests of a prespecified hypothesis. Fig. 2 shows the evolution of estimates of the difference Δ(3,1)=EY(3)−Y(1) over time; Fig. 3 shows the asymptotic distribution of studentized test statistics of the form (Δ^T−Δ)/V^T1/2 for each estimator at the end of a long (T=105) experiment; and Fig. 4 shows arm-value statistics. Additional results are shown in SI Appendix, section A.

Fig. 2.

Evolution of estimates of Q(3)−Q(1) across simulation settings for different experiment lengths. Error bars are 95% CIs around averages across 105 replications.

Fig. 3.

Histogram of studentized statistics of the form (Δ^T−Δ)/V^T1/2 for the difference in arm values Δ(3,1)=EYt(3)−Yt(1) at T=105. Numbers are aggregated across over 105 replications.

Fig. 4.

Estimates of the bad-arm value Q(1) and good-arm value Q(3) at T=105. Error bars are 95% CIs around averages across 105 replications.

Figs. 2 and 4 show that, although the AIPW estimator with uniform weights (labeled as “unweighted AIPW”) is unbiased, it performs very poorly in terms of root-mean-square error (RMSE) and CI width. In the low- and high-signal case, its problem is that it does not take into account the fact that the bad arm is undersampled, so its variance is high; in the no-signal case, it yields studentized statistics that are far from normal, as we see in Fig. 3.

Figs. 2 and 4 show that our adaptively weighted AIPW estimators perform relatively well, and normal CIs around them have roughly correct coverage. We see that these estimators do have approximately normal studentized statistics in Fig. 3. Note that even in our longest experiments, in high-signal settings, the bad arm receives only around 50 observations, which suggests that normal approximation does not require an impractical number of observations. Of these two methods, two-point allocation better controls the variance of bad-arm estimates by more aggressively downweighting “unlikely” observations associated with large inverse propensity weights; this results in smaller RMSE and tighter CIs.

As mentioned in the introduction, the sample mean is downwardly biased for arms that are undersampled. Fig. 4 shows that this bias can be nonmonotonic in signal strength. In the high-signal case, the probability of pulling the bad arm decays so fast that very few observations are assigned to it. Most of these come from the beginning of the experiment, when the algorithm is still exploring, and sampling is less adaptive, resulting in smaller bias. In the no-signal case, the bias is small because the good and bad arms have the same value. In some simulations, one arm or another is discarded, and its estimate is biased downward; in others, it is collected heavily, and its estimate is nearly unbiased. Averaging over these scenarios results in the low bias we observe. Between these extremes, in the low-signal case, the bad arm is usually collected for some period and then discarded, so its bias is larger in magnitude. For this estimator, naive CIs based on the normal approximation are invalid, with severe undercoverage when there’s little or no signal. On the other hand, the nonasymptotic confidence sequences of ref. are conservative, but often wide.

These simulations suggest that, in similar applications, the adaptively weighted AIPW estimator with two-point allocation [] and the sample mean with confidence sequences based on ref. should be preferred. These two methods have complementary advantages. In terms of mean-squared error, the sample mean often performs better, in particular, in the presence of stronger signal. As for inference, normal intervals around the adaptively weighted estimator with two-point allocation have asymptotically nominal coverage, while confidence sequences are often conservative and wider than those based on normal approximations; however, the former is valid only at a prespecified horizon, while the latter is valid for all time periods and allows for arbitrary stopping times. Finally, in terms of assumptions, the adaptively weighted estimator requires knowledge of the propensity scores, and its justification requires that the propensity scores decay at a slow enough rate; the nonasymptotic confidence sequences for the sample mean require no restrictions on the assignment process and can be used even with deterministic methods such as Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) algorithms (), but require knowledge about other aspects of the distribution of potential outcomes, such as their support or an upper bound on their variance (ref. , section 3.2).

Related Literature

Much of the literature on policy evaluation with adaptively collected data focuses on learning or estimating the value of an optimal policy. The classical literature (e.g., ref. ) focuses on strategies for allocating treatment in clinical trials to optimize various criteria, such as determining whether a treatment is helpful or harmful relative to control. Ref. generalizes this substantially, addressing the problem of optimally allocating treatment to estimate or testing a hypothesis about a finite-dimensional parameter of the distribution of the data. In optimal-allocation problems, the undersampling issue we address by adaptive weighting does not arise, as undersampling treatments relevant to the estimand or hypothesis of interest is suboptimal.

Ref. considers the problem of policy evaluation when treatment is sequentially randomized, but otherwise unrestricted. The estimator they propose in their section 10.3, when specialized to the problem of estimating an arm value, reduces to the AIPW estimator []. They establish asymptotic normality of their estimator under assumptions, implying that a nonnegligible proportion of participants is assigned the treatment of interest throughout the study. Ref. proposes a stabilized variant of this estimator, which, similarly specialized, reduces to the adaptively weighted estimator with constant allocation rates []. The applicability of this approach to bandit problems is mentioned in ref. . Ref. considers a similar refinement of an analogous weighted-average estimator ([]) for batched adaptive designs.

Drawing on the tradition of debiasing in high-dimensional statistics, ref. proposes a method that can be used to estimate policy values in noncontextual and linear-contextual bandits. Their approach, W-decorrelation, yields consistent and asymptotically normal estimates of linear-regression coefficients when the covariates have strong serial correlation. For multiarmed bandits, where the arm indicators are used as the covariates, their estimates of arm values take the form

where

Nw,t is the number of times arm

w was selected up to period

t,

Ȳw,T is the sample average of its rewards at

T, and

λ is a tuning parameter. We include a numerical evaluation of W-decorrelation in

SI Appendix, section A, finding it to produce arm-value estimates with high variance.

Discussion

Adaptive experiments such as multiarmed bandits are often a more efficient way of collecting data than traditional randomized controlled trials. However, they bring about several new challenges for inference. Is it possible to use bandit-collected data to estimate parameters that were not targeted by the experiment? Will the resulting estimates have asymptotically normal distributions, allowing for our usual frequentist CIs? This paper provided sufficient conditions for these questions to be answered in the affirmative and proposed an estimator that satisfies these assumptions by construction. Our approach relies on constructing averaging estimators, where the weights are carefully adapted so that the resulting asymptotic distribution is normal with low variance. In empirical applications, we have shown that our method outperforms existing alternatives, in terms of both mean squared error and coverage.

We believe this work represents an important step toward a broader research agenda for policy learning and evaluation in adaptive experiments. Natural questions left open include the following.

What other estimators can be used for normal inference with adaptively collected data? In this paper, we have focused on estimators derived via the adaptively weighted AIPW construction []. However, this is not the only way to obtain normal CIs For example, in the setting of Theorem 2, one could also consider the weighted-average estimator

Asymptotic normality of this estimator essentially follows from Theorem 2 (

SI Appendix, section C.4). In our numerical experiments, we found its performance to be essentially indistinguishable from that of the adaptively weighted estimator defined as in []. We’ve focused on [] because it readily allows formal study in a more general setting; however, the simpler estimator [] is appealing in the special case of evaluating a single arm. For a more general discussion of the relationship between augmented estimators like

Q^h and variants like

Q^h-avg in adaptive experiments, see ref. .

What should an optimality theory look like? Our result in Theorem 2 provides one recipe for building CIs using an adaptive data-collection algorithm like Thompson sampling, for which we know the treatment-assignment probabilities. Here, however, we have no optimality guarantees on the width of these CIs. It would be of interest to characterize, e.g., the minimum worst-case expected width of normal CIs that can be built by using such data.

How do our results generalize to more complex sampling designs? In many application areas, there’s a need for methods for policy evaluation and inference that work with more general designs, such as contextual bandits, and in settings with nonstationarity or random stopping.

Confidence intervals for policy evaluation in adaptive experiments

Confidence intervals for policy evaluation in adaptive experiments