Edited by James A. Estes, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA, and approved October 22, 2020 (received for review February 11, 2020)

Author contributions: J.M., H.H., and B. Wachter designed research; J.M., S.K.H., B. Wasiolka, R.M., S.T., I.P., A.W., R.P., R.R., M.K., and B. Wachter performed research; J.M. and B. Wachter contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.M. and H.H. analyzed data; and J.M., M.K., H.H., and B. Wachter wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

The cheetah is a prominent example for human–carnivore conflicts and mitigation challenges. Its global population suffered a substantial decline throughout its range. Here, we present an in-depth and new understanding of the socio-spatial organization of the cheetah. We show that cheetahs maintain a network of communication hubs distributed in a regular pattern across the landscape, not contiguous with each other and separated by a surrounding matrix. Cheetahs spend a substantial amount of their time in these hubs, resulting in high local cheetah activity, which represents a high local predation risk for livestock. Implementing this knowledge, farmers were able to reduce livestock losses by 86%.

Human–wildlife conflicts occur worldwide. Although many nonlethal mitigation solutions are available, they rarely use the behavioral ecology of the conflict species to derive effective and long-lasting solutions. Here, we use a long-term study with 106 GPS-collared free-ranging cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) to demonstrate how new insights into the socio-spatial organization of this species provide the key for such a solution. GPS-collared territory holders marked and defended communication hubs (CHs) in the core area of their territories. The CHs/territories were distributed in a regular pattern across the landscape such that they were not contiguous with each other but separated by a surrounding matrix. They were kept in this way by successive territory holders, thus maintaining this overdispersed distribution. The CHs were also visited by nonterritorial cheetah males and females for information exchange, thus forming hotspots of cheetah activity and presence. We hypothesized that the CHs pose an increased predation risk to young calves for cattle farmers in Namibia. In an experimental approach, farmers shifted cattle herds away from the CHs during the calving season. This drastically reduced their calf losses by cheetahs because cheetahs did not follow the herds but instead preyed on naturally occurring local wildlife prey in the CHs. This implies that in the cheetah system, there are “problem areas,” the CHs, rather than “problem individuals.” The incorporation of the behavioral ecology of conflict species opens promising areas to search for solutions in other conflict species with nonhomogenous space use.

Human–wildlife conflicts (HWC) are a global challenge and likely to increase in the future (1). Carnivore species are often involved in such conflicts because they prey on, or are feared to prey on, livestock. With the increasing human population and concurrent growth in livestock numbers, contact between carnivores, people, and their livestock will increase, and so will predation on livestock (2). Today, retaliatory killing of carnivores is still a common response to the perceived or actual threat of carnivore predation on livestock and can be a major threat to endangered carnivores (3). Nonlethal mitigation tools are therefore essential and also used widely, such as predator-proof bomas, kraals or electric fences (e.g., against lions (Panthera leo) (4)), livestock guarding dogs (e.g., against cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) (5)), light or sound deterrents (e.g., against cougars (Puma concolor) (6)), compensation payments (e.g., African wild dogs (Lycaon pictus) (7)), beef from certified carnivore-friendly farmers (e.g., gray wolves (Canis lupus) (8)), translocations (e.g., cheetahs (9)), and bylaw changes (e.g., lions (10)). These methods were successful in some cases; in others, they failed (2, 78910–11).

The rapidly developing field of movement ecology with its substantial improvements of tracking devices and analysis tools has unlocked new approaches in conservation science (12). In the context of HWC, collaring and tracking of conflict species already provided successful applications in geofencing and early warning systems (13). Their warning signals facilitate quick responses of livestock herders or owners to an approaching carnivore provided they are on continuous standby (13). Here, we present a method that takes advantage of this rapidly developing field of movement ecology and provides an effective and long-lasting solution to mitigate a long-term conflict between livestock farmers and a threatened carnivore, the cheetah.

Conflicts between farmers and cheetahs are well documented and are a major threat to the global cheetah population, as most cheetahs occur on farmland outside protected areas (14). In this study, we focused on cheetahs on Namibian farmland, where cheetahs are the key wild carnivore to kill cattle calves because lions and spotted hyenas (Crocuta crocuta) were extirpated decades ago (15). Building on previous work, we analyzed the space use and socio-spatial ecology of Namibian farmland cheetahs in detail, developed a modification of livestock management, and experimentally tested its efficacy in substantially reducing livestock losses. This led to the development of recommendations for new management practices for cattle farmers that minimize calf losses.

Cheetah males begin their adult life-history career as floaters (16, 17), living in large home ranges (in Namibia of 1,595 km2) which overlap with both female home ranges (mean, 650 km2) and several small territories (mean, 379 km2) of male territory holders (17). Floaters either wait for a territory to become vacant (queuing system) or compete and fight with territory holders to take over a territory (17). This regularly results in the death of either the territory holders or the challengers and suggests that territories contain valuable resources, most likely preferred access to females (1617–18). Both floaters and territory holders may be solitary or form coalitions of two to three males, often brothers (16, 17). For this study, we used telemetry data of 106 cheetah individuals to show that in an area where all territorial male units (solitary males or coalitions) were collared, the small territories of cheetah males were distributed in a regular pattern across the landscape and, more importantly, that the territories were not contiguous with each other but were separated by a surrounding matrix. This results in farms containing a cheetah territory, or parts of it, and farms not containing any cheetah territory. Because cheetah males fight over territories, we predict that the location and shape of the territory remains approximately constant across successive territory holders. If so, then the same farms contain (or do not contain) a cheetah territory over successive territory holders, and hence different farm owners experience different levels of conflicts with cheetahs.

If territories remain stable over time, we also predict that scent-marking locations operated by territory holders (16, 17) are traditional, “culturally maintained” sites used by several successive territory holders. These scent-marking locations play an important role in the communication of cheetahs (16, 17). They are marked at high frequencies by territory holders; are regularly visited by floaters, which do not mark but only collect information; and are occasionally visited and marked by females, typically when they are in estrus (16, 17). Thus, the scent-marking locations function as information centers for animals where territory defense and information exchange at a local population level are performed (19). They are often large trees (formerly termed “play trees” (20)) but can be any conspicuous structure (e.g., rocks). Scent-marking locations were typically concentrated in the core area of territories, so we termed them “communication hubs” (CHs) of cheetahs. We defined the core areas with CHs as the 50% kernel density estimator (KDE50) of the Global Positioning System (GPS) locations (“fixes”) of the territory holders (see Results). Since each CH was visited by several floaters and females, their home ranges substantially overlapped with the CHs and with each other. On average, each floater and female home range encompassed three CHs and four CHs, respectively (see Results). Each floater unit (solitary floaters or floater coalitions) spent a considerable amount of its time in the CHs (see Results). As a result of the frequent presence of territory holders and regular visits of several floater units in each CH (17), the CHs were local hotspots of cheetah activity and density.

We hypothesize that predation risk should be substantially higher in CHs than in the surrounding matrix if the frequency of cheetah hunts is positively related to the number of cheetahs present in an area and the time spent there. If these areas are also used for cattle herds with calves under 6 mo of age (the animals most susceptible to predation by cheetahs), then CHs would be hotspots for cheetah–farmer conflicts. Thus, farmers containing a full CH or part of a CH on their farm are predicted to face higher cattle calf losses by cheetahs than farmers not containing a CH on their farm—a pattern consistent with some farmers reporting heavy losses and others reporting little or no losses. Furthermore, we predict that cattle calf losses can be substantially reduced when suckler herds with calves are shifted away from CHs. If cheetahs in CHs do not follow cattle herds to their new location in another “camp” (i.e., a fenced subsection on the farm permeable for wildlife but not for cattle), then we predict that this simple management adjustment would be the key to substantially reduce farmer–cheetah conflict.

Results

Distribution of CHs and Overlap with Farms.

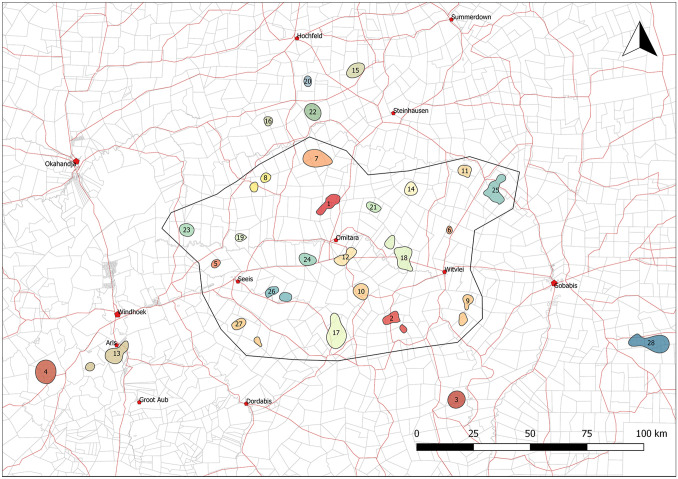

Within the study area, we identified 28 cheetah male territories. The 28 corresponding CHs, that is, the KDE50 of the GPS fixes of territory holders, had an average size (± SD) of 41.3 ± 24.7 km2 (95% CI: 32.2 to 50.5 km2, Fig. 1). The distribution of the CHs was significantly more regular than expected (i.e., overdispersed, SI Appendix, Fig. S1), with average distances between centroids of neighboring cheetah hubs of 22.9 ± 4.0 km (95% CI: 21.6 to 24.3 km, n = 38).

The location and extent of 28 cheetah communication hubs. The size and location of communication hubs correspond to the area covered by the KDE50 of GPS fixes of territory holders. The different colors indicate different CHs of cheetahs. In seven cases, the KDE50 revealed two neighboring centers within individual CHs, indicated by the same color. Eight CHs were omitted from the analyses of floater visits because not all floater units visiting CHs were fitted with a GPS collar. The thick-lined gray polygon encompasses the remaining 20 CHs and represents the core study area of 10,553 km2. The thin-lined light gray polygons represent farm borders. One unit of the scale bar represents 25 km.

Six territory holders temporarily owned two neighboring territories at the same time, but all of them eventually gave up on one of them within 12 mo. At first, the two territories belonged to two different units of territory holders until one territory became vacant (e.g., because the respective cheetah unit was eliminated by farmers). This vacant territory was taken over by a neighboring territorial unit until they were eventually challenged by a floater unit and gave up one of the territories.

For seven territories, the KDE50 of the territory holders revealed two separate areas (Fig. 1). These two areas had an average distance between centroids of 8.14 ± 0.77 km (95% CI: 6.18 to 10.1 km) and were regarded as one, albeit bipolar, CH of the same territory.

Movement data from visiting floaters were analyzed for 20 neighboring CHs, thereby covering a study area of 10,553 km2, including the surrounding matrix and encompassing 278 farms (Fig. 1). The 20 CHs covered a total area of 764.9 km2, or 7.2% of the study area. The 278 farms within the core study area had an average size of 45.8 ± 20.7 km2 (95% CI: 43.3 to 48.2 km2). Of those, 84 farms (30.0%) contained a CH or parts of a CH, with a median overlap of 6.5 km2 and the median percentage of overlap between the CH and the individual farm being 13.1% of the farm. In five farms, the CHs covered more than 50.0% of the farm (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). If the cheetah territories were dotted around the landscape according to a random process, for instance a simple Poisson process, then the nearest distances between neighboring territories would substantially vary, and the degree of overlap between particular farms and territories would similarly vary at random. We therefore compared the distribution of the degree of overlap between cheetah territories and individual farms with a simple Poisson process. The degree of overlap was more frequently higher than would be expected from a random distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, dmax = 0.694, P < 0.0001). Such a deviation from a random process emphasized a regular, nonrandom, overdispersed distribution pattern of CHs, also with respect to farm delineations.

Stability of Core Areas of Territories and Marking Locations over Time.

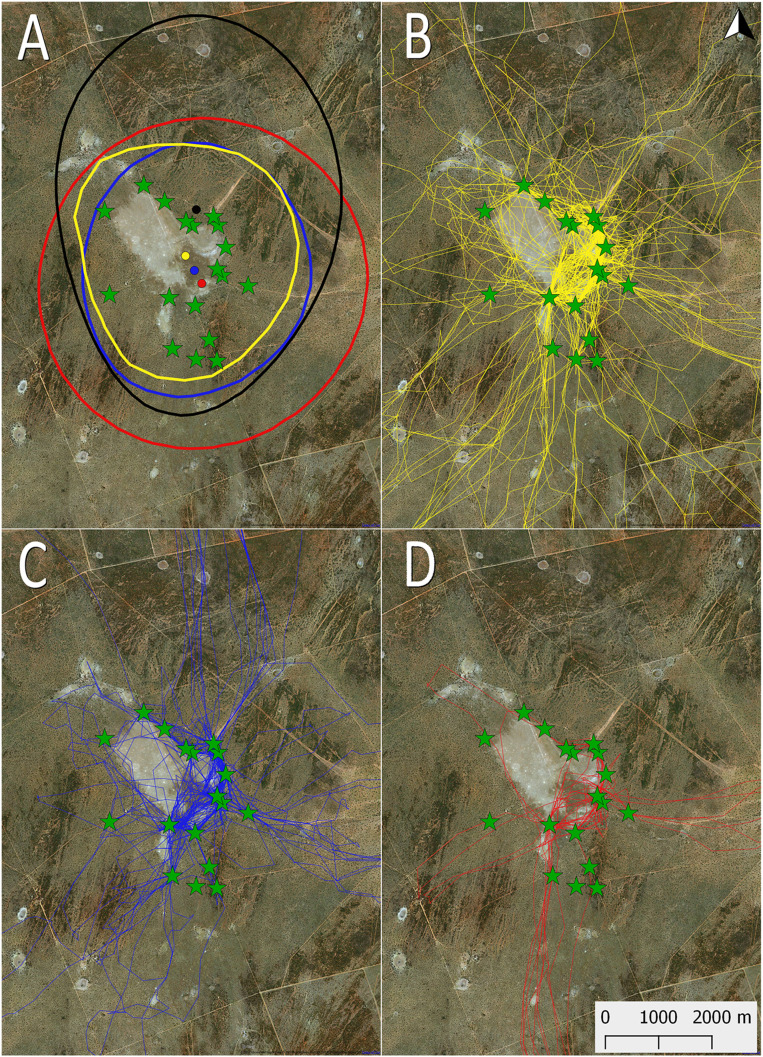

During the study period, we observed in seven territories a change in ownership several times (n_2 successive territory holders = 2, n_3 successive territory holders = 1, n_4 successive territory holders = 4, SI Appendix, Table S1; for an example, see Fig. 2A). The average overlap of the core areas between two successive territory holders was 71.0% (SI Appendix, Table S1). The centroids of the KDE50 of consecutive territory holders were, on average, 1.9 km apart (95% CI: 0.9 to 2.9 km, n = 16, SI Appendix, Table S1). In four cases (25%), the new territory holders shifted the core area by more than 3.0 km (average = 4.7 km, 95% CI: 3.0 to 6.3 km, SI Appendix, Fig. S3). If these cases were omitted, the average distance between centroids was 0.9 km (95% CI: 0.5 to 1.4 km, n = 12).

The CHs of consecutive territory holders. The size and location of CHs correspond to the area covered by the KDE50 of GPS fixes of successive territory holders. (A) The four KDE50 areas of the territory holders of CH number 16 (see Fig. 3 for CH number) and the corresponding centroids are depicted as dots. The temporal order of the territory holders was from black to yellow to blue to red. The green stars represent marking locations, which were typically located in and around the CH. (B–D) The movement paths of the yellow, blue, and red territory holders. The green stars represent marking locations.

Incoming territory holders typically used the same scent-marking locations as the previous owner(s) as exemplified in Fig. 2 B–D. Most (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) or all (Fig. 2 B–D) marking locations were located within the CHs.

High Utilization of CHs by Cheetahs.

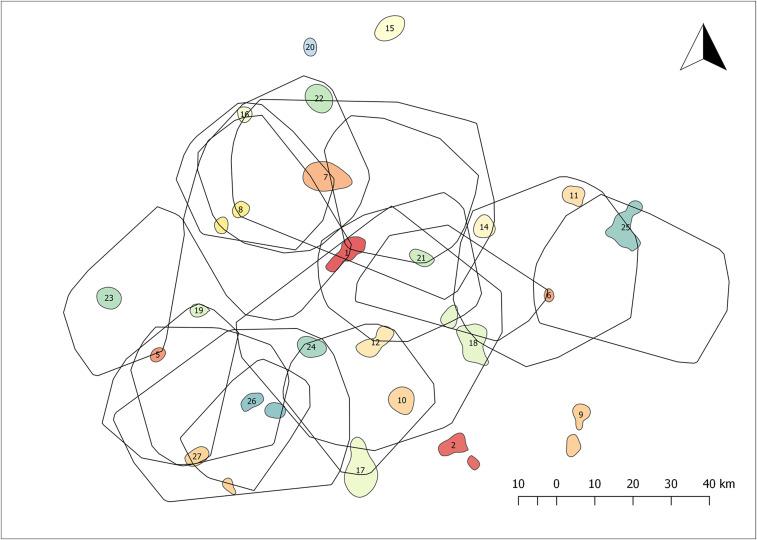

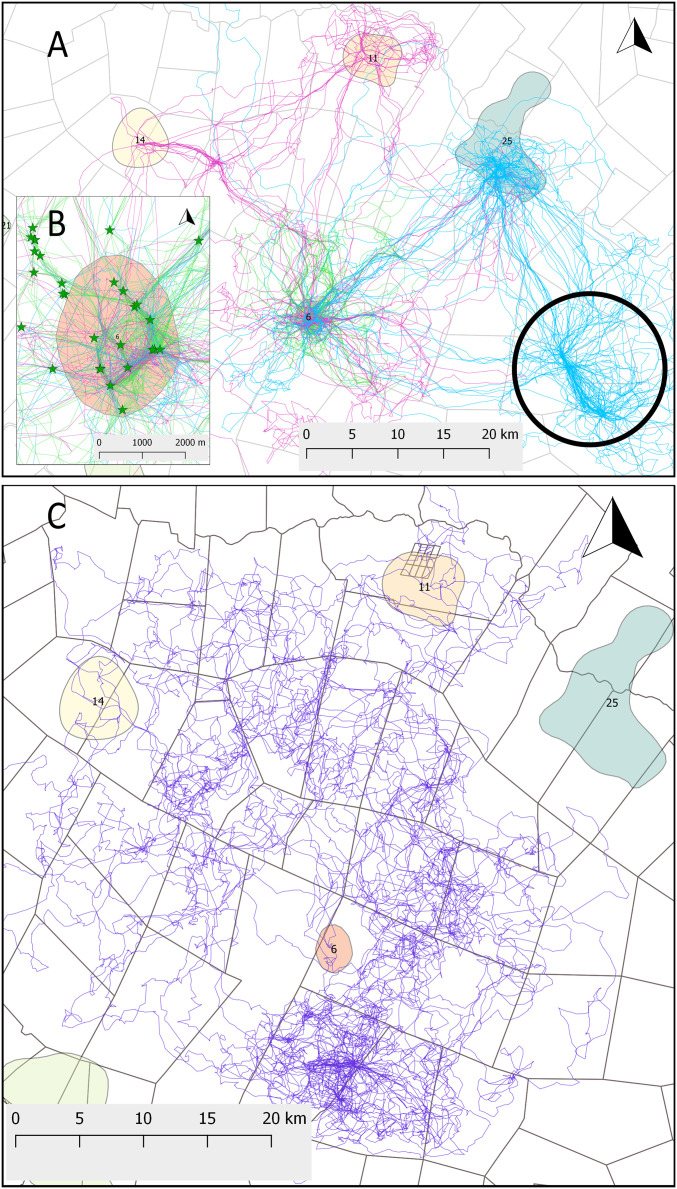

As per the definition, territory holders spent 50% of their time inside CHs. In addition, floater units frequently visited CHs within their home ranges and spent, on average, 23.5 ± 13.3% (95% CI: 18.3 to 28.7%, n = 25) of their individual observation periods (average 14 mo) inside these areas. In comparison, CHs comprised, on average, 8.5 ± 2.9% (95% CI: 7.4 to 9.6%, n = 25) of the home range areas of the floaters. The time spent in CHs indicated a strong preference for these areas (paired t test, P < 0.001, n = 25). The floater units visited, on average, 3.3 ± 1.9 CHs (95% CI: 2.6 to 4.1, n = 25, Figs. 3 and 4 A and B). The home ranges of floaters showed substantial overlap between each other (Figs. 3 and 4 A and B).

The home ranges of floaters show a wide overlap between individuals. The home ranges are drawn as 95% MCP. The size and location of communication hubs (CH) correspond to the area covered by the KDE50 of GPS fixes of territory holders. The number for each CH is indicated in the center of each CH.

The movement path of floaters and females visiting the CHs of territory holders. (A) Two floater units (pink and blue lines) oscillating between four and three CHs, respectively. The black circle marks a CH indicated by the frequent revisits of the blue floater unit. Based on this, marking locations can be found, and traps are placed to capture the territory holder(s) to confirm the CH. The green lines represent the movements of the territory holder of CH number 6. The gray polygons represent farm borders. (B) The movements and visits of the marking locations of all animals within CH number 6. The green stars indicate sites of marking locations. (C) The purple lines represent the movement path of a female over 4 y. The cluster in the south of the range indicates a lair where the female spent most of her time during the first 2 mo after giving birth. For the location and numbers of CHs, see Fig. 3.

Females spent, on average, 4.0 ± 2.6% (95% CI: 2.0 to 6.0%, n = 10) of their time (average observation period, 23 mo) inside CHs. In comparison, the CHs comprised, on average, 5.7 ± 3.1% (95% CI: 3.5 to 7.9%, n = 10) of the home range areas of the females. This indicated an avoidance of these areas (paired t test, P = 0.032, n = 10). Females visited, on average, 3.9 ± 2.8 CHs (95% CI: 1.8 to 5.9, n = 10, Fig. 4C).

Density of Floaters in and Around CHs.

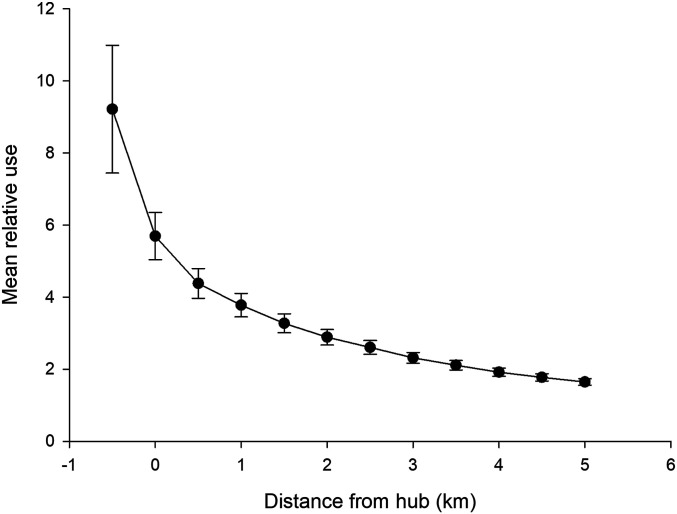

Within each CH, there were territory holders present (solitary or coalitions) plus a varying number of floater units (solitary or coalitions) visiting the CH. The relative space use of floater units (n = 25) decreased exponentially with increasing distance from the border of the CHs (Fig. 5).

The mean relative habitat use of floaters in relation to the distance of CHs. The relative use of the landscape was measured along a gradient of increasing buffers in 0.50-km steps around the borders (0 km) of the CHs. The number of GPS fixes in each buffer was divided by the corresponding buffer area, averaged across all floater units (n = 25), and presented as a reciprocal index with error bars.

Losses of Cattle Calves.

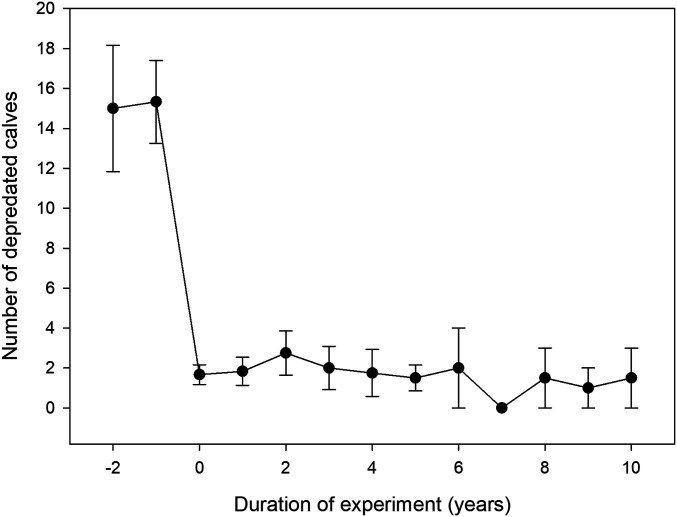

Farmers with at least an area of 6.5 km2 of the farm (the median of the 89 affected farms) overlapping with a CH and monitoring their calf numbers on a quantitative level experienced substantial losses of cattle calves. They had a mean of 15.0 ± 7.1 (n = 5 farms) lost calves 2 y and 15.3 ± 5.1 (n = 6 farms) lost calves 1 y before the experimental management measures started (Fig. 6). With a price for a weaner of approximately US$350 during the study period, the observed losses prior to management adjustments reached approximate values of between $2,100 (= 6 calves) and $7,700 (= 22 calves) per year per farm where these losses were quantitatively monitored. This corresponded to a mean of $5,250 ± $2,475 (n = 5) lost 2 y and a mean of $5,250 ± $1,779 (n = 6) lost 1 y before experimental management adjustments. The most affected farmer (who was not a participant of this experiment) had a loss of 33 calves worth $11,550.

The number of losses before and after the experimental shifting of suckler herds out of CHs. Six farmers shifted suckler herds out of cheetah CHs and recorded losses 2 y prior to and after the intervention (year 0). Four out of these six farmers systematically monitored their losses for up to 8 additional years. The CHs of the farms were monitored throughout the period over which the farmers recorded their losses.

Once farmers adjusted their farm management by shifting suckler herds away from the location of known CHs, the number of calves lost to predation by cheetahs decreased, on average, by 86% (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, P = 0.027, n = 6, Fig. 6) in the quantitatively monitored farms. None of the CHs shifted when the farmers shifted their breeding herds away from the CHs, as evidenced by continuous monitoring of the territory holders and their CHs for several years (Fig. 6). Thus, the CHs were areas with high conflict potential or “problem areas” rather than cheetahs in the CHs being “problem individuals.” In 25 other farms, with more than 6.5 km2 overlap with a CH, farmers reported a qualitative assessment of changes, if any, in calf losses. Two reported that there was no change after experimental management adjustments were introduced, and 23 reported that there was a substantial decline in their losses (sign test, P < 0.0001, n = 25).

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that on farmland in central Namibia, livestock losses were drastically reduced when breeding herds were experimentally shifted away from areas of high cheetah activity and density, and losses continued to remain low for several years, delivering a sustainable solution for this conflict. These areas were the CHs of cheetahs, the core areas determined from the KDE50 of the GPS fixes of territory holders, which encompassed numerous scent-marking locations. While the KDE50 is a technical definition of cheetah CHs, in practice, these areas were well delineated by marking trees recognizable in the field and often known to the farmers (see below), thereby facilitating the recognition of CHs.

Distribution of Cheetah Territories.

We demonstrated that the territories of cheetah males were distributed in a regular pattern across the landscape and were not contiguous with each other. The surrounding matrix rarely contained any marking trees and was mainly used by females to raise their offspring and by floaters to travel from one territory to another. Floaters spent a considerable amount of time in the CHs. They were therefore highly reliable indicators of CHs and also allowed the confirmation of potential unknown CHs of territory holders (Fig. 4A). We are therefore confident that we identified all territories in the core study site (Fig. 1).

The availability of cattle calves is unlikely to be the driving factor of this distribution pattern, as this factor varies with the season and because cheetahs did not follow the suckler herds when these were shifted. Wildlife prey species are distributed approximately evenly across the farmland because the widely distributed water places on farms discourage large-scale migration movements of wildlife. The overdispersed distribution of the CHs therefore suggests that there is an approximately constant cost/benefit function such that the average distance ensures that there are sufficient resources (high benefits) and simultaneously minimizes the chance of dangerous encounters with neighbors (reduced costs). The high benefit is most likely preferred access to females (18).

Some territory holders temporarily owned two territories. This likely increased their access to preferred resources but might also require additional investment in defending the CHs. In areas with lower cheetah density, it might be feasible for cheetah males to own two territories over longer time periods. This was also described in lions occurring at low density (21) or occurring in areas with a high rate of anthropogenic removal of males (22), where males occupied the areas of several prides of females.

Indications for CHs, Locally Varying Activity, and Regular Spacing in Other Studies.

Previous studies described sites with locally high cheetah population densities (16, 2324–25). A study on spatial movements of pooled data from four male units and three females on three farms in north-central Namibia reported high-use and low-use areas by cheetahs on farmland (24).

In the Serengeti National Park (NP) in East Africa, a region with a different ecological and management context, the spatial organization of male territories was very similar. Territories were not contiguous, and they were also distributed in a regular pattern across the landscape and used for communication among cheetahs (16). Interestingly, the distances between the centroids of the territories were ∼20 km (estimated from Fig. 8.5 in ref. 16), similar to the average of 22.9 km in our study.

A recent study in the Maasai Mara landscape in Kenya, adjacent to the Serengeti NP, described “hotspots” of cheetah densities (25). The areas with high densities (n = 7) were distributed in a regular pattern with distances of ∼20 km. It is unknown whether these areas correspond to the spatial distribution of territories described in our study or the Serengeti NP (16), as the areas included pooled sightings of territory holders, floaters, and females, and the sex ratio in the study population was biased toward females (approximately five females to every one male).

In summary, there is some evidence from other areas that the socio-spatial system of cheetahs described here is a general phenomenon.

High versus Low Predation Risk Areas Provide the Key to Reduce Livestock Losses.

If breeding cattle herds are unwittingly kept within a CH, losses of calves can be substantial. Although cheetahs do not preferentially prey on livestock species (26, 27), they will readily prey on cattle calves when available. When the suckler herds were experimentally moved away from hubs to other cattle camps of the farm, losses declined drastically because cheetahs did not pursue the breeding herds.

The calf losses reported by farmers (Fig. 6) refer to confirmed cases of predation by cheetahs. As the numbers of losses were impossible to verify by us, we had to rely on the reports of farmers. We think that the credibility of these numbers was enhanced by the motivation of the farmers to participate in the development of a solution to reduce their livestock losses. The farmers therefore had a genuine economic interest in providing correct information. We were unable to run strict controls, since no farmer on whose farm a CH was located was willing to keep his suckler herds within the area of CHs to satisfy the requirements to be a control farm for the experiment. Despite this limitation, the substantial decrease in the cattle calf losses before and after experimental shifts of suckler herds strongly suggests that this management method was highly effective. During the course of this study, we identified 28 CHs affecting 89 farms. On 45 farms, the CHs covered more than 6.5 km2. Of those, 25 farmers adapted their herd management accordingly, and 92% reported a decrease of their losses based on our scientific information.

Our findings have important implications. First, one key insight is that there are “problem areas” or “conflict-prone areas,” the CHs, rather than “problem individuals.” This might lead to a reappraisal of the prevalent assumption that cheetahs hunting livestock on Namibian farmland must be problem individuals and thus have to be dealt with as such. Secondly, the matrix surrounding cheetah hubs is relatively safe to keep suckler herds, without the need for expensive protection measures. Cheetahs occurring in a “problem area” and killing livestock might still be perceived as “problem animals,” but such individuals are not problem animals in the sense of habitual livestock killers (28) and will not seek livestock once moved to a different area. Predation risk by cheetahs in the matrix between the CHs does exist, and farmers sometimes also lose calves to cheetahs in these areas. These losses are much lower and typically in a range which most farmers find acceptable. As cheetah females focus their movements on the matrix between the CHs, such predation may be largely their effort. Females are solitary or with their offspring and roam in large home ranges of on average 650 km2 in central Namibia (17), encompassing ∼14 farms. They use their entire home range and thus, in principle, distribute their potential predation impact across a large area. Nevertheless, females with offspring can remain for several weeks in a relatively small area of their home range (29), hence inducing locally and temporally aggregated cattle calf losses to particular farmers. An adjustment of breeding herd management might also be possible in such cases, but female movements in the matrix are expected to be less predictable than male movements.

Adjustment of Breeding Herd Management.

A successful implementation of knowledge on CH locations into grazing management of breeding cattle herds requires enough alternative grazing grounds. This is not always available. If need be, CHs could be used for the grazing of adult cattle or oxen. It is not possible to set a threshold for a critical overlap area of a CH with the farm because the grazing area which remains available depends on the logistics and characteristics of the individual farm. In difficult cases, additional management measures might be required, such as supplementary feeding of herds in safe areas of the farm or some form of cooperation with neighboring farmers in the matrix of lower cheetah activity during the calving season. It is therefore helpful to develop for and with each farmer a tailored solution for his farm if the research capacity to do so is available. This is likely to produce sustainable, long-lasting solutions because CHs were stable over time, consistent with earlier results (16) reported from the Serengeti.

There is also anecdotal evidence from farmers that cheetah territories are stable over time. Some farmers containing a CH on their farm reported that some marking trees on their farm were already known by their ancestors. Because cheetah males queue for territory ownership, the direct elimination of territory holders will likely increase the turnover of territory holders and therefore increase rather than decrease cheetah activity and associated predation risk in CHs (17). This would be similar to increased livestock losses following a disrupted social organization because of lethal removal of cougars in North America (30).

Although the locations of CHs generally remained stable over time, we observed some small-scale shifts of the centroids between successive territory holders. Depending on farm logistics and characteristics, such a distance might indicate a laborious change in the adjustment of handling breeding herds. An average farm in central Namibia of 45.8 km2 has a diameter of 6.8 km if shaped as a square, thus a shift of a CH centroid by several kilometers might be challenging. This is a second reason to avoid an accelerated turnover in territory ownership through the lethal elimination of territory holders. As natural changes in territory ownership do occur, one cheetah per known CH should be monitored for several years to provide data for the grazing management of breeding herds.

The home ranges of floaters encompass several CHs, which they visit on a frequent basis. These regular visits of GPS-collared floaters result in a distinct spatial pattern of GPS fixes and trajectories, which allows for the detection of CHs in previously unstudied areas (Fig. 4A). Where data from GPS-collared cheetahs are not available, searching for assemblages of “active” marking trees as “biomarkers” for CHs and applying the average distance between neighboring CHs should yield informative results. If farmers suspect a CH on their farm and are trained on how to identify marking trees in the field, they could observe cheetah activity at the trees by visiting the trees and inspecting them for fresh markings or by using low-cost camera traps to record cheetah visits at the trees. This information will likely help them to get a good idea of which direction and how far suckler herds should be shifted.

Perspectives for Other Cheetah Populations and Other Species.

We demonstrated that the socio-spatial organization of the cheetah had a major influence and simultaneously offered an effective solution for the farmer–cheetah conflict in Namibia. It is likely that our solution to the conflict is also applicable to other cheetah populations. Information from other areas suggests that cheetahs are responsible for a substantial share of livestock losses across their range in Africa (SI Appendix, Table S2). As noted above, the distance of 20 to 25 km between CHs might be applicable to many populations. Therefore, we think that our solution can also be applied in other areas of the cheetah range without the need for a long-term project on site. Depending on local characteristics and available resources, there are some mitigation options that can be achieved relatively quickly. When GPS data are available, CHs can be identified on maps and verified in the field. When no GPS data are available, clusters of active marking sites need to be searched for. Herders and farmers typically know some marking sites of cheetahs, which gives a good start to search for clusters of marking sites and thereby identify the CH and thus the main conflict area. The typical assumption of locals is to assume, with their focus on their own land (a relatively small spatial perspective), that marking sites, cheetah activity, and cheetah distribution are continuously distributed. With the knowledge that the matrix between the CHs is a safe area for livestock and by applying the average distance to the next CH as an estimate, it should be possible to identify safe areas in the landscape.

Although most other carnivore species operate other forms of socio-spatial organization and their occupied area rarely contains a matrix undefended by any individual, they do not use their home ranges in a uniform manner. For example, some habitat features operate as attractors and increase local space use, such as riparian vegetation for brown bears (Ursus arctos) (31). Scent-marking sites of carnivores, such as Eurasian lynx (Lynx lynx) (32), Sunda clouded leopard (Neofelis diardi) (33), leopard (Panthera pardus) (34), snow leopard (Panthera uncia) (35), gray wolf (36, 37), spotted hyena (38), and European badger (Meles meles) (39), are often frequently visited, can include conspicuous locations such as latrines, and are distributed unevenly across the landscape, particularly when linked to key habitat features (32), and can include conspicuous locations such as latrines. Even more pronounced causes for concentrated space use, ubiquitous among carnivores, are dens and other breeding sites during the period when juveniles are immobile (38, 404142–43). As these sites are visited disproportionally more frequently than other sites, they could represent areas with an increased conflict risk for a farmer, as has been demonstrated for denning sites of wolves (44, 45) and wolverines (Gulo gulo) (43) and for habitat features that attract brown bears (31). There are also sites visited disproportionally less frequently than others, such as territory overlaps of neighboring gray wolf packs, which were previously identified as providing naturally safe areas for wild ungulates (46). Quantifying the proportion of these particular areas in relation to the entire home range and the relative time carnivores spent in these areas might be useful to provide cues to identify the potential conflict hotspots where livestock is more vulnerable. Our approach of considering the behavioral ecology of a carnivore species and close collaboration with the people affected by HWCs might open a promising area for future conflict mitigation (research) and inspire new and sustainable solutions.

Materials and Methods

Study Animals.

We captured, immobilized, and collared 106 free-ranging cheetahs at scent-marking trees in the territories of territory-holding males as previously described (17). If males were part of a coalition, we attempted to also capture the other coalition members. We fitted one coalition partner with a GPS collar and the other(s) with a very high frequency (VHF) collar, or they were not collared, because we previously showed that the coalition partners always stay together (17). Only fully grown adult cheetahs entered the analyses of this study. These were 69 male units (44 units of territory holders (n = 67 individuals) and 25 units of floaters (n = 29 individuals)) and 10 females, collared between 2007 and 2018 in central Namibia. The relatively low number of females is a consequence of females rarely visiting marking trees in male territories.

We fitted the animals with accelerometer-equipped GPS collars (e-obs GmbH) which recorded GPS fixes every 15 min when the animal moved and every 360 min when the animal was resting. As soon as the animal started moving again, the higher schedule was triggered. On average, the collars recorded 46 GPS fixes per day; gaps were filled using the last known position when resting started. The battery lifetime of GPS collars lasted up to 36 mo, but collars were exchanged earlier when animals were recaptured to extend information on the animals. A total of 14 cheetahs were fitted with a GPS collar which took two fixes per day during dusk and dawn, that is, times of high activity (Vectronics Aerospace GmbH). The GPS data were retrieved through regular aerial tracking flights (17).

We defined the core area of a territory as the KDE50, the area in which 50% of all fixes of each animal were located. Because KDE50 is sensitive to the number of fixes, we used only the last full year of GPS data for all territory holders. Territory holders tend to decrease the frequency of excursions with increasing duration of tenure. The KDE50 estimates of younger territory holders with recently acquired territories are typically larger (see Fig. 3, communication hubs 7, 17, and 25 versus 5, 6, and 16). The centroids were calculated from the area within the isopleth of each KDE50. All spatial analyses except for the distribution of the CHs (see below) were calculated in R version 3.5.1 using package rhr (47) for the calculation of KDEs and minimum convex polygons (MCPs).

Study Area.

Our study area was located in central Namibia. It is characterized by thornbush savannah and encompasses ∼1,000 privately owned farms. The main farming activity is cattle ranching with a stocking density of 0.12 km2 per large livestock unit. A farm has an average size of ∼45 km2; thus, a farm contains, on average, 375 cattle and is fenced along the entire border (48). The farms are further divided by internal fences into camps, each with access to water from boreholes. The cattle are regularly shifted between camps to ensure that they graze in an optimal manner across the farm.

The study started with a core group of ∼35 farmers organized in a conservancy who were willing to enroll in a research project and engage in the development of the study design (49). Their motivation was to actively participate in the finding of evidence-based mitigation solutions to reduce their cattle calf losses and thus increase their economic revenue. They were ready to document their losses and open to change their management practices if these practices provided them with a higher benefit than killing cheetahs. During the course of the study and with the first successful experiments of shifting suckler herds away from the CHs, more farmers and other conservancies joined the study.

Wild ungulates, which are potential prey species for cheetahs, are common on cattle farms. These include eland (Taurotragus oryx), greater kudu (Tragelaphus strepsiceros), red hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus), gemsbok (Oryx gazella) and adult warthog (Phacochoerus africanus), springbok (Antidorcas marsupialis), common duiker (Sylvicapra grimmia), steenbok (Raphicerus campestris), and scrub hare (Lepus saxatilis) (26, 27). The cattle fences are constructed in such a way that they allow these species, as well as cheetahs, to move freely between camps (see below). Few farmers erected high game fences (∼3.2 m) that prevent the movement of bigger species but typically allow smaller mammals (including cheetahs) to pass underneath the fence. An unknown number of leopards and brown hyenas (Hyaena brunnea) also occur. Lions and spotted hyenas were extirpated on farmland in central Namibia at the beginning of the 20th century (15).

Spatial Distribution, Use, and Inheritance of CHs.

To investigate whether the centroids of all CHs were regularly distributed, we used the L-transformation of Ripley’s K function using the software Programita (50). As we did not know all CHs in the modeled rectangular grid (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), we implemented a null model based on a heterogenous Poisson process and used a moving window with a fixed bandwidth of 30 km, that is, a distance larger than the expected effect. Hence, patterns may only be interpreted up to a radius of 30 km from a centroid of a CH (51). To estimate the average distance between neighbors, we measured the distance between centroids of neighboring hubs.

To determine the average overlap of CHs between successive territory holders, we first determined the average overlap between the successive territory holder (two, three, or four successions, SI Appendix, Table S1) of the same CH (n = 6), averaged within each CH and then between CHs, to estimate a population average.

The use of CHs by floaters and females was determined separately for the sexes. To assess whether cheetahs preferred or avoided CHs, we determined for each individual the sum of GPS fixes within all visited CHs and the number of total GPS fixes. Similarly, we determined for each individual the MCP area inside all visited CHs and the total MCP area. If the former ratio was higher (or lower) than the latter, then the ratio of the two would be above (or below) 1, equivalent to Manly’s wi (52) and indicating preference for (or avoidance of) CHs. The ratio of the former was then compared with the ratio of the latter, separately for the sexes, using a paired t test. For this analysis we used data of floaters and females within the black polygon in Fig. 1, encompassing the 20 neighboring CHs for which we had the most detailed information. Within this black polygon, we knew all existing CHs.

The relative use of the landscape was measured along a gradient of increasing buffers in 500-m steps around the borders of CHs. The number of GPS fixes in each buffer was divided by the corresponding buffer area, averaged across all floater units (n = 25), and presented as a reciprocal index.

Identification of Marking Trees.

The marking trees were identified from clusters of GPS locations of territorial males because such trees were frequently visited (17). These clusters were visited by us in the field to verify that they were actively used marking trees. Such marking trees all had feces on the trunk and/or branches and sometimes also scratching signs or urine. We also systematically visited every prominent tree outside the territory represented by CH number 6 (Fig. 3) within a radius of 20 km and in the area until we reached the border of the next territory in the north-east represented by CH number 25 (Fig. 3). We did this during the same time period that we verified the used marking trees in territories represented by CH numbers 6 and 25 in Fig. 3. We did not find any trees with cheetah feces in the matrix outside the territory and therefore assumed that this was also true for the rest of the matrix surrounding the other territories.

Determination of Losses of Cattle Calves.

We selected the farmers for the experiment to shift the suckler herds away from the CHs from ∼35 farmers of the first conservancy that participated in our study. Of these farmers, six had a CH on their farm and high losses and thus were highly suitable for the experiment. Farmers with high losses had a high economic interest in providing correct information that helped to develop and verify mitigation solutions to reduce their livestock losses from cheetah predation. The experiments started in different years as the identification of the newly identified CHs progressed in the study area.

All calves had an identification number and were recorded in a logbook, a requirement of the veterinary service from Namibia to get permission for selling cattle and thus increase reliability of cattle recordings by farmers. Farmers typically shifted cattle from one camp to another in a rotational grazing regime such that over the year, all available vegetation was utilized in a sustainable way. They counted the calves when they shifted the herds from one camp to another and when the calves were earmarked or needed veterinary services such as vaccinations.

We were in regular contact with the farmers to retrieve their data on the number of cattle calves they had lost from cheetah predation. The six farmers from the first conservancy recorded their losses in a quantitative way over many years. An additional 25 farmers with CHs on their farms recorded their losses prior to shifting herds in a less-comprehensive qualitative way. We therefore separated the analyses of these two groups of farmers. The cattle calf losses reported by the six farmers who collected high-quality data were always confirmed losses to cheetahs, that is, the farmers found cattle carcasses in the field or spoors and signs they could unambiguously interpret. Reported losses of the other 25 farmers were not necessarily always confirmed losses to cheetahs, but we assumed that potentially wrong assignments to cheetah predation were similar (i.e., random) before and after the application of our developed cattle-management regime.

Statistical Analysis.

Lilliefors tests revealed that the ratio of GPS fixes inside CHs and total fixes and the ratio of MCPs inside CHs and total MCPs of floaters and females, respectively, were normally distributed. The ratios of GPS fixes and MPCs were separately compared for floaters and females using a paired t test. All other data were not normally distributed, and thus Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used (53). These tests were conducted with SYSTAT 13.0 (Systat Software Inc.), and results are reported as means ± SD with 95% confidence limits, unless stated otherwise.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism for permission to conduct the study; the farmers of the Seeis, Hochfeld, and Auas Oanob Conservancies for cooperation; B. Foerster and H. Foerster, whose preparatory work provided the basis for the cooperation with the conservancies; the late U. Herbert and N. Louw for conducting aerial tracking flights; and all team members, including volunteers, for their help in the field. Special thanks go to M. Fischer, S. Streif, S. Edwards, V. Menges, S. Goerss, D. Bockmuehl, and B. Brunkow for their tireless work in the field, air, and office. We also thank S. Getzin, who provided advice for the analyses of spatial distributions, and M. Franz for fruitful discussions. We thank F. Kuemmeth and his team from e-obs for outstanding electronical engineering work. We further thank D. Boras, B. Kehling, P. Sobtzick, W. Tauche, S. Vollberg, and G. Liebich for administrative and technical support and three reviewers for very helpful comments that significantly improved the manuscript. We are deeply grateful to the Messerli Foundation Swizerland; this study would not have been possible without their generous, long-term support. We thankfully received additional funding from WWF-Germany and the German Academic Exchange Service.

Data Availability.

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author (J.M.). The data are not publicly available because of the conservation status of the species and a growing market of its products, such as skin, bones, and teeth.

References

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Communication hubs of an asocial cat are the source of a human–carnivore conflict and key to its solution

Communication hubs of an asocial cat are the source of a human–carnivore conflict and key to its solution