Contributed by Roger A. Nicoll, December 1, 2020 (sent for review October 29, 2020; reviewed by David S. Bredt and Eunjoon Kim)

Author contributions: Y.F., A.N., S.F., R.A.N., and M.F. designed research; Y.F., R.A.N., and M.F. supervised the project; Y.F., X.C., S.C., Y.H., A.Y., H.I., M.S., H.S., T.G., M.H., S.F., R.A.N., and M.F. performed research; H.-C.K. and H.P. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Y.F., X.C., S.C., Y.H., A.Y., H.S., A.N., S.F., R.A.N., and M.F. analyzed data; and Y.F., S.C., A.N., S.F., R.A.N., and M.F. wrote the paper.

Reviewers: D.S.B., Johnson and Johnson; and E.K., Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology.

1Y.F. and X.C. contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

This study addresses a fundamental question in neuroscience, namely how does the presynaptic component of the synapse precisely align with the postsynaptic component? This is essential for the proper transmission of signals across the synapse. This paper focuses on a set of transsynaptic, epilepsy-related proteins that are essential for this alignment. We show that the LGI1–ADAM22–MAGUK complex is a key player in the nanoarchitecture of the synapse, such that the release site is directly apposed to the nanocluster of glutamate receptors.

Physiological functioning and homeostasis of the brain rely on finely tuned synaptic transmission, which involves nanoscale alignment between presynaptic neurotransmitter-release machinery and postsynaptic receptors. However, the molecular identity and physiological significance of transsynaptic nanoalignment remain incompletely understood. Here, we report that epilepsy gene products, a secreted protein LGI1 and its receptor ADAM22, govern transsynaptic nanoalignment to prevent epilepsy. We found that LGI1–ADAM22 instructs PSD-95 family membrane-associated guanylate kinases (MAGUKs) to organize transsynaptic protein networks, including NMDA/AMPA receptors, Kv1 channels, and LRRTM4–Neurexin adhesion molecules. Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 knock-in mice devoid of the ADAM22–MAGUK interaction display lethal epilepsy of hippocampal origin, representing the mouse model for ADAM22-related epileptic encephalopathy. This model shows less-condensed PSD-95 nanodomains, disordered transsynaptic nanoalignment, and decreased excitatory synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Strikingly, without ADAM22 binding, PSD-95 cannot potentiate AMPA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission. Furthermore, forced coexpression of ADAM22 and PSD-95 reconstitutes nano-condensates in nonneuronal cells. Collectively, this study reveals LGI1–ADAM22–MAGUK as an essential component of transsynaptic nanoarchitecture for precise synaptic transmission and epilepsy prevention.

Epilepsy, characterized by unprovoked, recurrent seizures, affects 1 to 2% of the population worldwide. Many genes that cause inherited epilepsy when mutated encode ion channels, and dysregulated synaptic transmission often causes epilepsy (1, 2). Although antiepileptic drugs have mainly targeted ion channels, they are not always effective and have adverse effects. It is therefore important to clarify the detailed processes for synaptic transmission and how they are affected in epilepsy.

Recent superresolution imaging of the synapse reveals previously overlooked subsynaptic nano-organizations and pre- and postsynaptic nanodomains (345–6), and mathematical simulation suggests their nanometer-scale coordination in individual synapses for efficient synaptic transmission: presynaptic neurotransmitter release machinery and postsynaptic receptors precisely align across the synaptic cleft to make “transsynaptic nanocolumns” (7, 8).

So far, numerous transsynaptic cell-adhesion molecules have been identified (91011–12), including presynaptic Neurexins and type IIa receptor protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTPδ, PTPσ, and LAR) and postsynaptic Neuroligins, LRRTMs, NGL-3, IL1RAPL1, Slitrks, and SALMs. Neurexins–Neuroligins have attracted particular attention because of their synaptogenic activities when overexpressed and their genetic association with neuropsychiatric disorders (e.g., autism). Another type of transsynaptic adhesion complex mediated by synaptically secreted Cblns (e.g., Neurexin–Cbln1–GluD2) promotes synapse formation and maintenance (1314–15). Genetic studies in Caenorhabditis elegans show that secreted Ce-Punctin, the ortholog of the mammalian ADAMTS-like family, specifies cholinergic versus GABAergic identity of postsynaptic domains and functions as an extracellular synaptic organizer (16). However, the molecular identity and in vivo physiological significance of transsynaptic nanocolumns remain incompletely understood.

LGI1, a neuronal secreted protein, and its receptor ADAM22 have recently emerged as major determinants of brain excitability (17) as 1) mutations in the LGI1 gene cause autosomal dominant lateral temporal lobe epilepsy (18); 2) mutations in the ADAM22 gene cause infantile epileptic encephalopathy with intractable seizures and intellectual disability (19, 20); 3) Lgi1 or Adam22 knockout mice display lethal epilepsy (212223–24); and 4) autoantibodies against LGI1 cause limbic encephalitis characterized by seizures and amnesia (252627–28). Functionally, LGI1–ADAM22 regulates AMPA receptor (AMPAR) and NMDA receptor (NMDAR)-mediated synaptic transmission (17, 22, 29) and Kv1 channel-mediated neuronal excitability (30, 31). Recent structural analysis shows that LGI1 and ADAM22 form a 2:2 heterotetrameric assembly (ADAM22–LGI1–LGI1–ADAM22) (32), suggesting the transsynaptic configuration.

In this study, we identify ADAM22-mediated synaptic protein networks in the brain, including pre- and postsynaptic MAGUKs and their functional bindings to transmembrane proteins (NMDA/AMPA glutamate receptors, voltage-dependent ion channels, cell-adhesion molecules, and vesicle-fusion machinery). ADAM22 knock-in mice lacking the MAGUK-binding motif show lethal epilepsy of hippocampal origin. In this mouse, postsynaptic PSD-95 nano-assembly as well as nano-scale alignment between pre- and postsynaptic proteins are significantly impaired. Importantly, PSD-95 is no longer able to modulate AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission without binding to ADAM22. These findings establish that LGI1–ADAM22 instructs MAGUKs to organize transsynaptic nanocolumns and guarantee the stable brain activity.

Results

ADAM22 Participates in the Transsynaptic Protein Network Involving MAGUKs.

We first performed an unbiased proteomic screening to identify the ADAM22-mediated protein network in the brain. We generated the ADAM22 knock-in mouse harboring a tandem tag composed of FLAG, AU1, and HA (referred to as an FAH tag) (Adam22FAH/FAH mouse) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A), which ensures the specificity of experiments when wild-type mice are used as a negative control. Adam22FAH/FAH mice were viable and an Adam22FAH/+ mouse showed no detectable differences in the protein expression level between wild-type ADAM22 and ADAM22-FAH in the brain (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Given that all ADAM22 homozygous knockout mice (Adam22−/−) die within 3 wk after birth due to multiple seizures (23), we concluded that ADAM22-FAH protein is functional.

To comprehensively identify ADAM22-containing protein complexes involving detergent-resistant synaptic proteins, we employed a stringent condition with a zwitterionic detergent (Fos-Choline-14 [FC-14]) for protein solubilization. The membrane fraction of mouse brains was extracted with a low (1% Triton X-100) or high (2% FC-14) stringency buffer. ADAM22-FAH was then immunoprecipitated using anti-FAH antibody from the Adam22FAH/FAH or wild-type mouse brain extract. The bands obtained from Adam22FAH/FAH mouse brains are highly specific as we saw few bands from wild-type mouse brains under both conditions (Fig. 1A). Consistently, label-free quantitative proteomics with tandem mass spectrometry showed the specific enrichment of target proteins in the eluates from Adam22FAH/FAH mouse brains (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1C).

![ADAM22 participates in transsynaptic protein networks involving MAGUKs. (A) In vivo ADAM22-associated protein complex purified from Adam22FAH/FAH knock-in mouse brain. Protein names identified by in-gel digestion-based mass spectrometry are shown. Asterisks indicate immunoglobulin heavy chain. FAH, a tandem-tag composed of FLAG, AU1, and HA epitope tags; IP, immunoprecipitation. (B) Synaptic ADAM22-associated protein network under the high stringency condition. Volcano plot of protein enrichments between Adam22FAH/FAH knock-in and wild-type mice (negative control). Two hundred thirty-four proteins were significantly enriched in ADAM22-FAH samples (n = 4 replicates). Thresholds for enrichment are shown by gray dashed lines. Color codes for classification are indicated (and apply to A–D). Smaller light gray dots, proteins with subthreshold values; gray dots above thresholds, proteins in other categories. All protein data (348 proteins) for the plot are shown in Dataset S2. (C and D) The identified specific proteins under the high stringency condition are lined up based on the protein functions and Mascot scores. Error bars show ± SEM (n = 4). (E) ADAM22-FAH and LGI1 colocalize with postsynaptic PSD-95 and presynaptic CASK in the hippocampus of an Adam22FAH/FAH mouse. Arrowheads indicate synaptic colocalization of ADAM22-FAH (labeled by HA antibody), PSD-95 or CASK, and LGI1 in the stratum lucidum (SL) in the CA3 region. (Scale bars: 20 μm [magnified, 5 μm].) SR, stratum radiatum; Py, stratum pyramidale; SO, stratum oriens. (F) Two-color (2C) STED imaging reveals coclusters of ADAM22-FAH (labeled by HA antibody) and LGI1 that are positioned at the synaptic cleft in the CA1 region. Bassoon (Bsn) and PSD-95 represent the presynaptic active zone and PSD, respectively. Asterisks indicate postsynaptic nanodomains of PSD-95. The graph shows the distances between cluster peaks of two tested molecules (red and green). P values were determined by Kruskal–Wallis with post hoc Scheffé test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant. n = 60 pairs (HA–LGI1); 107 (HA–PSD-95); 78 (HA–Bsn); 67 (Bsn–PSD-95). (Scale bar: 200 nm.)](/dataresources/secured/content-1765840310810-e51911bb-395e-4d6a-8bc7-b2da9ba0d512/assets/pnas.2022580118fig01.jpg)

ADAM22 participates in transsynaptic protein networks involving MAGUKs. (A) In vivo ADAM22-associated protein complex purified from Adam22FAH/FAH knock-in mouse brain. Protein names identified by in-gel digestion-based mass spectrometry are shown. Asterisks indicate immunoglobulin heavy chain. FAH, a tandem-tag composed of FLAG, AU1, and HA epitope tags; IP, immunoprecipitation. (B) Synaptic ADAM22-associated protein network under the high stringency condition. Volcano plot of protein enrichments between Adam22FAH/FAH knock-in and wild-type mice (negative control). Two hundred thirty-four proteins were significantly enriched in ADAM22-FAH samples (n = 4 replicates). Thresholds for enrichment are shown by gray dashed lines. Color codes for classification are indicated (and apply to A–D). Smaller light gray dots, proteins with subthreshold values; gray dots above thresholds, proteins in other categories. All protein data (348 proteins) for the plot are shown in Dataset S2. (C and D) The identified specific proteins under the high stringency condition are lined up based on the protein functions and Mascot scores. Error bars show ± SEM (n = 4). (E) ADAM22-FAH and LGI1 colocalize with postsynaptic PSD-95 and presynaptic CASK in the hippocampus of an Adam22FAH/FAH mouse. Arrowheads indicate synaptic colocalization of ADAM22-FAH (labeled by HA antibody), PSD-95 or CASK, and LGI1 in the stratum lucidum (SL) in the CA3 region. (Scale bars: 20 μm [magnified, 5 μm].) SR, stratum radiatum; Py, stratum pyramidale; SO, stratum oriens. (F) Two-color (2C) STED imaging reveals coclusters of ADAM22-FAH (labeled by HA antibody) and LGI1 that are positioned at the synaptic cleft in the CA1 region. Bassoon (Bsn) and PSD-95 represent the presynaptic active zone and PSD, respectively. Asterisks indicate postsynaptic nanodomains of PSD-95. The graph shows the distances between cluster peaks of two tested molecules (red and green). P values were determined by Kruskal–Wallis with post hoc Scheffé test. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant. n = 60 pairs (HA–LGI1); 107 (HA–PSD-95); 78 (HA–Bsn); 67 (Bsn–PSD-95). (Scale bar: 200 nm.)

The native ADAM22 protein complexes with a low stringency buffer included LGI family members (LGI1, LGI2, LGI3, LGI4), ADAM22 subfamily members (ADAM22, -23, -11), postsynaptic MAGUKs (PSD-95/Dlg4, SAP97/Dlg1, PSD-93/Dlg2, MPP3, MPP7), presynaptic MAGUKs (CASK/Lin2–MALS/Lin7–Apba/Lin10, SAP97), presynaptic Kv1 (Kcna) channels, and 14-3-3/Ywha proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D and Dataset S1). With a high stringency buffer, we found overlooked interactions of synaptic proteins with ADAM22, an array of MAGUK-binding transmembrane proteins: neurotransmitter receptors (NMDARs and AMPARs/Shisa7), ion channels (Kv1 and Kcnj), and cell-adhesion molecules (LRRTM4 and Neurexin) (Fig. 1 A–D and Dataset S2). Importantly, presynaptic components (Kv1, Neurexin, Cav [Cacnb] channels, Munc18/Stxbp1, and RIM1/Rims1) as well as postsynaptic proteins were significantly included in the ADAM22 protein complexes (Fig. 1 B–D). The relative abundance shows that ADAM22 most abundantly occurs with LGI1 and PSD-95 reflecting their direct interactions (Fig. 1C) and that LGI1–ADAM22 is furthermore linked with various pre- and postsynaptic transmembrane proteins through PSD-95–like MAGUKs (Fig. 1D).

Next, to determine the distribution of ADAM22 in the brain, we utilized Adam22FAH/FAH mice with the extracellular FAH tag. Anti-HA antibody specifically detected the ADAM22-FAH protein in the Adam22FAH/FAH mouse brain sections (i.e., no signals in wild-type sections) (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 A and B and S2A). Confocal imaging showed that ADAM22 and LGI1 were perfectly colocalized in the hippocampus (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Magnified images showed that the LGI1–ADAM22 complex was colocalized with clusters of postsynaptic and presynaptic MAGUKs, PSD-95 and CASK (Fig. 1E). To investigate the nanoscale ADAM22 localization, we used stimulated emission depletion (STED) superresolution microscopy. Extracellularly labeled ADAM22-FAH and LGI1 were concentrated together into clusters (∼40-nm distance around the resolution limitation of STED imaging) that were positioned almost equidistant (∼60 nm) from postsynaptic PSD-95 and presynaptic Bassoon, indicating the localization of ADAM22–LGI1 at the synaptic cleft (Fig. 1F). In addition, ADAM22 was well colocalized with Kv1 channels at the various subcellular regions, including the presynapse, axon initial segment, and cerebellar basket cell terminal (i.e., pinceau) as previously reported (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 C and D) (33).

Loss of the ADAM22 PDZ Ligand Causes Lethal Epilepsy of Hippocampal Origin in Mice.

To examine whether and how ADAM22 functions depend on the interaction with MAGUKs, we generated the ADAM22 knock-in mouse (Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5) lacking the C-terminal PDZ ligand (i.e., five amino acids) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B). We observed no changes in expression levels of ADAM22, LGI1, PSD-95, ADAM23, and Kv1 in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3C). Although all ADAM22 knockout mice die within 3 wk after birth (23), Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice appeared normal around this period and were fertile. However, Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice died suddenly starting after ∼60 d of life and none survived beyond 250 d (median life span: 124.0 ± 7.7 d) (Fig. 2B). Death of the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice was entirely unpredictable and often accompanied with tonic limb extension, possibly caused by the sudden, epileptic event.

![Loss of the ADAM22 PDZ ligand causes lethal epileptic seizures in mice. (A) Schematic presentation of ADAM22ΔC5, lacking a C-terminal PDZ-binding motif (–WETSI). Pro, prodomain; MP, inactive metalloprotease domain; DI, disintegrin domain; CR, cysteine-rich domain; EGF, EGF-like domain; TM, transmembrane domain. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curve of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (n = 32), showing completely penetrant lethality around postnatal 2 to 8 mo. (C) A typical example of an epidural EEG recording during a spontaneous seizure of an Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (P178). A triangle, the onset timing of seizure activity; lines with numbers, recording at a faster sweep speed. At the beginning, repetitive large sharp spike waves were observed (line with “1”). Later, spike wave amplitude decreased (line with “2”), pauses appeared (line with “3”), and finally the seizure activity stopped. This mouse died on P182 (mouse #2 in D). (D) Frequency of epileptic discharges in the epidural EEGs (mice #1 and 2) and hippocampal (HP) LFPs (mice #3 to 5) of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. The arrows indicate dates of death. (E) Typical examples of LFPs recorded simultaneously from the hippocampus (Upper) and sensorimotor cortex (Lower) at the early (P141, Left) and late (P147, Right) stages of the one and the same Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (#3 in D). This mouse died on P151. Raw LFPs, time-frequency maps, and power spectral densities are shown. Hz, hertz. (F) c-Fos expression was robustly up-regulated in the dentate granule cells and hilar interneurons of the hippocampus of an Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (P131) at 30 min after the first generalized seizure event. (Scale bars: [Upper] 1 mm; [Lower] 0.5 mm.)](/dataresources/secured/content-1765840310810-e51911bb-395e-4d6a-8bc7-b2da9ba0d512/assets/pnas.2022580118fig02.jpg)

Loss of the ADAM22 PDZ ligand causes lethal epileptic seizures in mice. (A) Schematic presentation of ADAM22ΔC5, lacking a C-terminal PDZ-binding motif (–WETSI). Pro, prodomain; MP, inactive metalloprotease domain; DI, disintegrin domain; CR, cysteine-rich domain; EGF, EGF-like domain; TM, transmembrane domain. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curve of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (n = 32), showing completely penetrant lethality around postnatal 2 to 8 mo. (C) A typical example of an epidural EEG recording during a spontaneous seizure of an Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (P178). A triangle, the onset timing of seizure activity; lines with numbers, recording at a faster sweep speed. At the beginning, repetitive large sharp spike waves were observed (line with “1”). Later, spike wave amplitude decreased (line with “2”), pauses appeared (line with “3”), and finally the seizure activity stopped. This mouse died on P182 (mouse #2 in D). (D) Frequency of epileptic discharges in the epidural EEGs (mice #1 and 2) and hippocampal (HP) LFPs (mice #3 to 5) of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. The arrows indicate dates of death. (E) Typical examples of LFPs recorded simultaneously from the hippocampus (Upper) and sensorimotor cortex (Lower) at the early (P141, Left) and late (P147, Right) stages of the one and the same Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (#3 in D). This mouse died on P151. Raw LFPs, time-frequency maps, and power spectral densities are shown. Hz, hertz. (F) c-Fos expression was robustly up-regulated in the dentate granule cells and hilar interneurons of the hippocampus of an Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (P131) at 30 min after the first generalized seizure event. (Scale bars: [Upper] 1 mm; [Lower] 0.5 mm.)

To define the epileptic phenotype, we then performed simultaneous video-epidural electroencephalography (EEG) recordings. The continuous video-EEG monitoring of the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse uncovered spontaneous ictal discharges characterized by large amplitude spike waves, developing into polyspike wave bursts (Fig. 2C). These abnormal EEGs were accompanied with progressive, complicated seizure behaviors with neck/trunk rotation, convulsion, and sometimes running/jumping (Movie S1). After the onset of epilepsy, seizure frequencies gradually increased over 14 to 20 d (approximately once/hour) and became very high (more than five times/hour) a few days before death (Fig. 2D). The seizure onset observed in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse was greatly delayed compared with that of Adam22−/− or Lgi1−/− mice (within 3 wk after birth) (212223–24).

To explore the epileptic focus in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice, we intracranially recorded local-field potentials (LFPs) from the hippocampus and sensorimotor cortex (Fig. 2E). At the early stage (postnatal day 141 [P141]; Fig. 2 E, Left), raw recordings and time-frequency maps showed that the first seizure activity occurred only in the hippocampus (indicated by “1”), but was not observed in the sensorimotor cortex. The second seizure activity occurred simultaneously in the hippocampus and sensorimotor cortex (indicated by “2”) and waxed (indicated by “3”). This suggests that seizure activity initiated in the hippocampus was propagated to the sensorimotor cortex with short latency. The amplitude of hippocampal seizure activity was larger than that of the sensorimotor cortical seizure activity. The frequency distribution of hippocampal and sensorimotor cortical seizure activity ranged from 2 to 90 Hz (delta–ripple) with several peaks including around 4 Hz. When seizure activity was confined in the hippocampus, the mouse looked normal without apparent behavioral seizures. After seizure activity spread to the sensorimotor cortex and waxed there, the mouse exhibited convulsion. At the later stage (P147; Fig. 2 E, Right), seizure activity occurred simultaneously in the hippocampus and sensorimotor cortex (indicated by “4”) and waxed (indicated by “5”), and the mouse showed convulsion. The time-frequency maps showed that both hippocampal and sensorimotor cortical seizure activities similarly behaved with larger amplitude of hippocampal activity. Their frequency distribution ranged from 2 to 90 Hz (delta–ripple), with several peaks including around 8 Hz. These observations strongly suggest the hippocampal origin of seizure activity in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice as observed in Lgi1−/− mice (21).

Consistently, immunohistochemical analysis showed that the expression of the neuronal immediate early genes, c-Fos and Arc, was robustly increased in the hippocampus, especially dentate granule cells and hilar interneurons, at 30 min after the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse showed epileptic seizures (Fig. 2F and SI Appendix, Fig. S3D), as in epileptic Lgi1−/− mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E). We confirmed that up-regulation of c-Fos signals was not observed in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse brain before the epilepsy onset. Neither major cell death nor hippocampal disorganization was evident from the nucleus staining of the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F). Thus, epileptic focus in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 and Lgi1−/− mice is located in the hippocampal network.

Supramolecular Complex of ADAM22–LGI1 Is Disrupted in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 Mice.

We next assessed biochemical alterations in the ADAM22 interactome of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. Whereas the interaction of the mutant protein ADAM22ΔC5 with extracellular LGI1 was intact (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A), the interactions with MAGUK proteins were lost (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). We next asked whether associations between ADAM22 and synaptic MAGUK-binding proteins are affected in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. NMDARs (GluN1 and GluN2B), Stargazin (a member of transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins [TARPs]), and LRRTM4 were coimmunoprecipitated with ADAM22 of wild-type mice, but not with ADAM22ΔC5 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). The interaction of ADAM22ΔC5 with Kv1.2 was greatly reduced, but slightly remained. These results indicate that ADAM22 indirectly associates with NMDARs, AMPARs, LRRTM4, and Kv1 on the MAGUK platform where ADAM22 binds to the third PDZ-SH3-GK domain of MAGUKs (17) and NMDAR, Stargazin, LRRTM4, and Kv1 bind to the first and second PDZ domains of MAGUKs (34).

Next, we performed blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) to see more directly how the native ADAM22 protein complex is changed in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse brain. When crude brain lysates solubilized with 1% Triton X-100 were separated with BN-PAGE, native ADAM22 occurred mainly in protein complexes with molecular masses of ∼1.2 and 1.0 MDa in the wild-type mouse brain as reported (35) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). LGI1 appeared in the same positions as ADAM22 on BN-PAGE, and the 1.2- and 1.0-MDa complexes for ADAM22 and LGI1 completely disappeared in Lgi1−/− mouse brain, indicating that ADAM22 and LGI1 coassemble to make supramolecular complexes. Strikingly, the 1.2- and 1.0-MDa supercomplexes of ADAM22 and LGI1 mostly disappeared in brain extracts from Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. In addition, we found that a subpopulation of Kv1.2 was a component of the 1.2-MDa ADAM22 complex, as it disappeared from the position in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. Given that ADAM22 is incorporated in the isolated PSD-95 or GluN1 supercomplexes with the similar molecular size on BN-PAGE (35), these data suggest that ADAM22 and LGI1 are recruited into very large protein complexes with pre- (e.g., Kv1) and postsynaptic transmembrane proteins (e.g., GluN1), depending on the ADAM22–MAGUK interaction.

Delocalization of PSD-95 and Dissociation of LGI1 from PSD-95 in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 Hippocampus.

As ADAM22 acts most abundantly on PSD-95 among MAGUK proteins (Fig. 1 B and C), we asked whether the loss of ADAM22 interaction affects postsynaptic clustering of PSD-95 in the hippocampus. The immunolocalization signals of PSD-95 were greatly reduced in hippocampal CA1 stratum radiatum, CA3 stratum lucida, and inner molecular layer of dentate gyrus (DG) in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 A–C). LGI1 clusters, mostly overlapped with PSD-95 clusters in the hippocampus of wild-type mice (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S5D), were less clustered and dissociated from residual PSD-95 in the hippocampus of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 D and E). A presynaptic vesicle protein, VGluT1, was hardly affected in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 D and F). We also found that PSD-95 clustering was completely lost in cerebellar basket cell terminals (Pinceau) and cerebellar juxtaparanodes (JXP) in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5G). Similarly, in the hippocampus of Lgi1−/− mice, we found reduction of PSD-95 (especially in the inner molecular layer of DG) and unaltered expression of VGluT1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). We noted that presynaptic localization of the Kv1 channels Kv1.1 and Kv1.2 was significantly reduced in the hippocampus of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Given that Kv1 channels are clustered with the aid of various MAGUKs such as PSD-93, PSD-95, SAP97, and MPPs (36, 37), these results suggest that LGI1–ADAM22 serves as a general regulator for an array of MAGUKs to scaffold functional transmembrane proteins.

Transsynaptic Nanoalignment Is Disordered in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 Hippocampus.

Recent superresolution imaging showed that PSD-95 forms subsynaptic nanometer-scale domains as postsynaptic building blocks (3, 38). STED superresolution observation revealed that LGI1 as well as ADAM22 were positioned closely to PSD-95 nanodomains in the wild-type mice (Fig. 1F), whereas LGI1 clusters were greatly decorrelated from PSD-95 nanodomains in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (Fig. 3A). Next we investigated how postsynaptic PSD-95 nano-organization is affected in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. The fluorescence intensity of PSD-95 in individual nanodomains and their size were significantly decreased in CA1 of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (Fig. 3 B and C), while the number of PSD-95 nanodomains was not altered (Fig. 3D). Thus, PSD-95 is less condensed within the nanodomains in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice, indicating that the LGI1–ADAM22–PSD-95 linkage is essential for building up the postsynaptic nanodomains.

![Transsynaptic nanoalignment is disordered in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 hippocampus. (A) Representative 2C-STED images of LGI1 and PSD-95 in the CA1 region of wild-type (+/+) or Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. Asterisks denote two or three adjoining nanodomains. (Scale bar: 500 nm.) (B–D) Quantification of the fluorescence mean intensity (B), size (C), and number (D) of PSD-95 nanodomains. (C and D) Nanodomains, when not completely separated, were quantified en bloc. P values were determined by a paired t test; n = 5 experiments (878 and 759 nanodomains were analyzed) (B) and by Mann–Whitney U tests; n = 5 experiments (C and D). (E) 2C-STED imaging unveils the disordered alignment between RIM2 (green) and PSD-95 (red) in the CA1 region of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. (Right) Intensity profiles of the nearest neighbor pair of RIM2 and PSD-95 were generated (e.g., along white dashed lines in the top images), and individual peak distances on the obtained intensity profiles were measured. (Scale bars: 500 nm [200 nm, magnified].) (F and G) Histograms, cumulative distributions (F, CA1 region), and dot plots (G, CA1 and DG) of the nearest neighbor distances between RIM2 and PSD-95, showing significantly larger distances between pre- and postsynaptic nanodomains in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 (gray) than in wild-type mice (+/+, black). ***P < 0.001 (Kolmogorov–Smirov test) (F) and Mann–Whitney U test (G; n = 4 experiments for RIM2–PSD-95; n = 3 experiments for RIM2–Homer1). Median distances (nm) are shown (G, red lines). Data with a <50-nm distance (gray area in G) were excluded.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765840310810-e51911bb-395e-4d6a-8bc7-b2da9ba0d512/assets/pnas.2022580118fig03.jpg)

Transsynaptic nanoalignment is disordered in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 hippocampus. (A) Representative 2C-STED images of LGI1 and PSD-95 in the CA1 region of wild-type (+/+) or Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. Asterisks denote two or three adjoining nanodomains. (Scale bar: 500 nm.) (B–D) Quantification of the fluorescence mean intensity (B), size (C), and number (D) of PSD-95 nanodomains. (C and D) Nanodomains, when not completely separated, were quantified en bloc. P values were determined by a paired t test; n = 5 experiments (878 and 759 nanodomains were analyzed) (B) and by Mann–Whitney U tests; n = 5 experiments (C and D). (E) 2C-STED imaging unveils the disordered alignment between RIM2 (green) and PSD-95 (red) in the CA1 region of Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. (Right) Intensity profiles of the nearest neighbor pair of RIM2 and PSD-95 were generated (e.g., along white dashed lines in the top images), and individual peak distances on the obtained intensity profiles were measured. (Scale bars: 500 nm [200 nm, magnified].) (F and G) Histograms, cumulative distributions (F, CA1 region), and dot plots (G, CA1 and DG) of the nearest neighbor distances between RIM2 and PSD-95, showing significantly larger distances between pre- and postsynaptic nanodomains in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 (gray) than in wild-type mice (+/+, black). ***P < 0.001 (Kolmogorov–Smirov test) (F) and Mann–Whitney U test (G; n = 4 experiments for RIM2–PSD-95; n = 3 experiments for RIM2–Homer1). Median distances (nm) are shown (G, red lines). Data with a <50-nm distance (gray area in G) were excluded.

The LGI1–ADAM22 ligand–receptor forms a 19-nm-long 2:2 heterotetrameric assembly, equivalent to the distance of the synaptic cleft (32). This finding, taken together with the present biochemical and STED imaging results, raises the possibility that LGI1–ADAM22 has a transsynaptic role. We then asked whether the transsynaptic nanoalignment between pre- and postsynapses is affected in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. We assessed the axial distribution of presynaptic RIM and postsynaptic PSD-95, both of which were included in the ADAM22-mediated protein networks (Fig. 1) and used as markers of transsynaptic alignment (8). Two-color STED imaging defined the apposed pre- and postsynaptic nanodomains (Fig. 3E) and showed that the average nearest neighbor distance between RIM2- and PSD-95 nanodomains was ∼115 nm (median = 115.6 [92.5 to 140.0] nm, 513 pairs) in the CA1 stratum radiatum of wild-type mice (Fig. 3 E–G). A comparable distance distribution had been previously described in cultured hippocampal neurons (between presynaptic RIM and postsynaptic GluA2) (7). Strikingly, the distance of RIM2–PSD-95 apposition was significantly larger in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (151.4 [124.0 to 184.8] nm, 407 pairs, P < 0.001 vs. wild type) (Fig. 3 E–G). Similar transsynaptic nano-organization was observed in the molecular layer of DG in wild-type mice, and the RIM2–PSD-95 apposition was significantly extended in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (113.9 [88.2 to 147.7] nm, 354 pairs in wild type; 152.0 [115.2 to 181.9] nm, 356 pairs in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5; P < 0.001) (Fig. 3G). On the other hand, we found no change in the distance between RIM2 and Homer1, another postsynaptic scaffold that positions at the more distal layer to the synaptic cleft (139.0 [112.2 to 166.5] nm, 523 pairs in wild type; 138.1 [115.4 to 168.6] nm, 489 pairs in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5; P = 0.700) (Fig. 3G). This result suggests that the overall synapse organization (i.e., the depth of synaptic cleft) is not changed in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice as in Lgi1−/− mice (39) and that the transsynaptic nanoalignment between RIM2 and PSD-95 is specifically disordered. Taken together with the result that LGI1–ADAM22 protein networks with pre- and postsynaptic proteins are disrupted in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 B–E), we conclude that LGI1–ADAM22 serves as an essential hub component of the transsynaptic nanocolumn architecture.

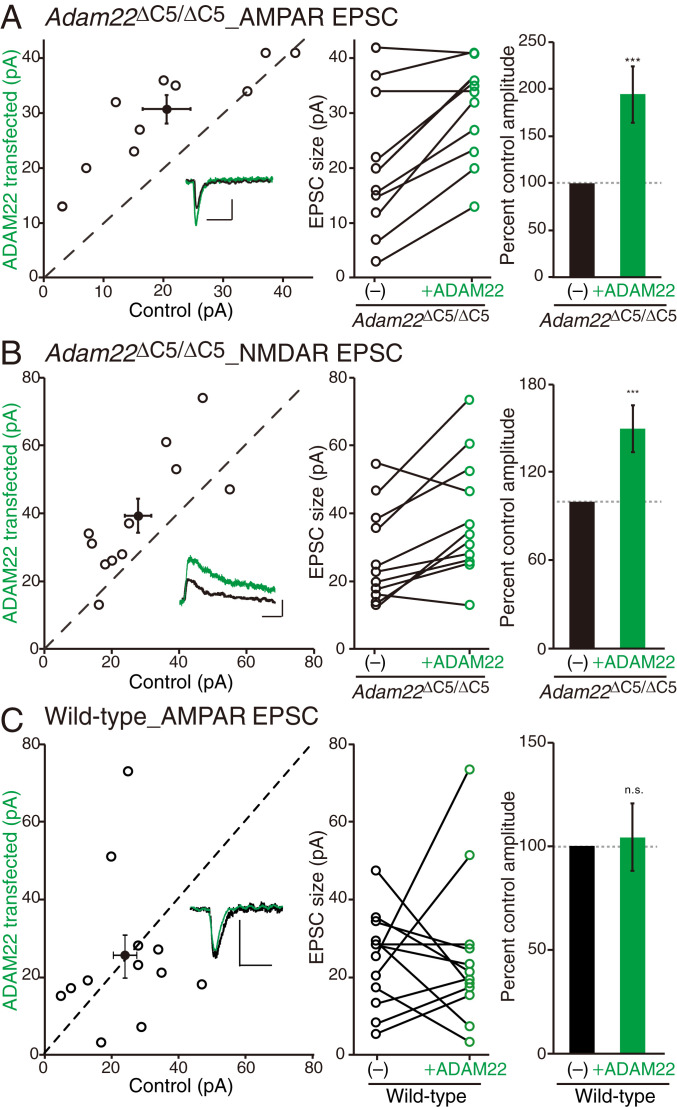

Excitatory Synaptic Transmission Is Decreased in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 Mice.

To determine the consequence of the ADAM22-PDZ ligand on glutamatergic synaptic transmission, we performed dual recording from wild-type ADAM22-transfected and neighboring untransfected CA1 neurons in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 hippocampal slice. This allowed us to directly compare AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission in the presence or absence of wild-type ADAM22. We found that AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission was significantly increased in ADAM22-transfected Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons, expressing ADAM22ΔC5 (endogenous) and wild-type ADAM22 (exogenous) (Fig. 4 A and B). This positive effect of ADAM22 transfection could be due to either of two possibilities: 1) overexpression of wild-type ADAM22 potentiates the current in any neurons or 2) expression of wild-type ADAM22 rescues the defect of the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neuron. To distinguish between these two alternatives, we set up the same dual recording from the wild-type mouse brain slices. In this case, ADAM22 overexpression failed to increase AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission (Fig. 4C). The selective effect of ADAM22 overexpression in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons indicates that the glutamate receptor-mediated excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) were decreased in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons. To further examine a role of LGI1 association in the ADAM22 function, we used the ADAM22 W396D mutant which expresses at the cell surface but has no binding to LGI1 (32). Expression of ADAM22 W396D in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons did not increase AMPAR- and NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A), indicating that LGI1 binding is required for synaptic function of ADAM22. Thus, LGI1–ADAM22–MAGUK interaction is necessary for glutamatergic synaptic transmission.

Excitatory synaptic transmission decreases in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. (A and B) Simultaneous dual recording of AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission in CA1 of ADAM22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (A). When ADAM22 was overexpressed (green) in ADAM22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons, AMPAR EPSC size greatly increased, as compared to the neighbor, nontransfected control ADAM22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons (black). The same setup was used to examine NMDAR-mediated synaptic transmission, and similar results were obtained (B). Scatterplots show individual dual recordings (open circles) and mean ± SEM (filled circle). (Insets) Representative EPSC traces. (Scale bars, 50 ms and 25 pA.) Bar graphs showing the normalized mean EPSC ± SEM. ***P = 0.0006, n = 10 pairs (A); ***P = 0.0007, n = 11 pairs (B). (C) Overexpression of ADAM22 does not increase AMPAR EPSCs in CA1 neurons of wild-type mice. n.s., not significant; n = 12 pairs.

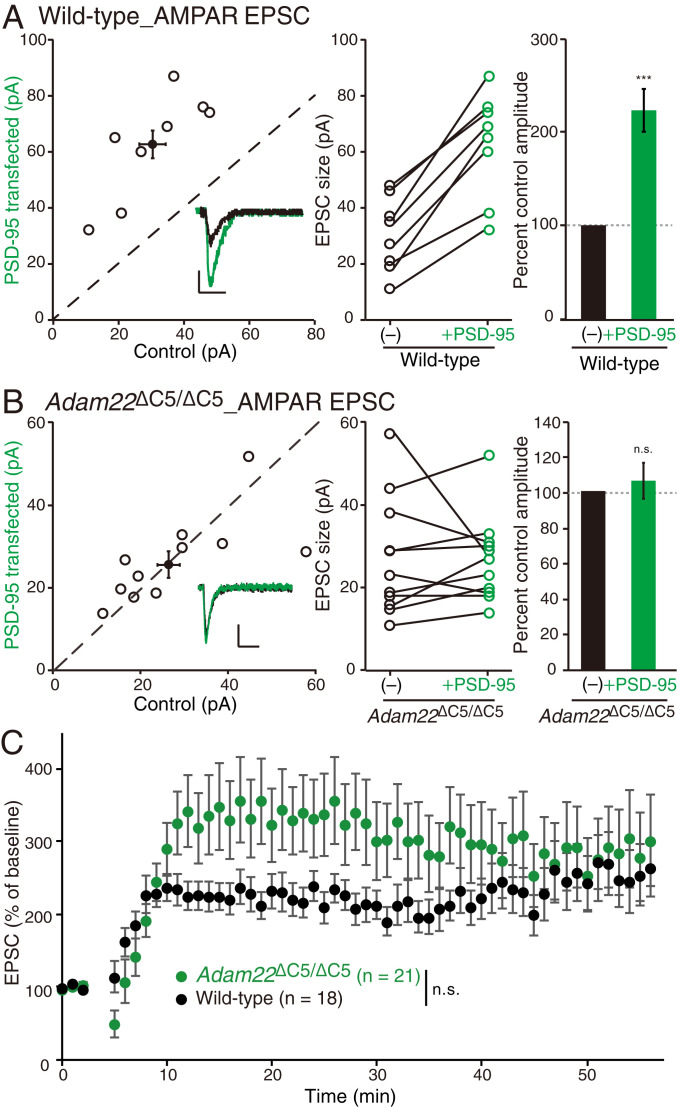

PSD-95 Function Requires Its Interaction with ADAM22.

It is well-established that overexpression of PSD-95 specifically enhances AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission (40). In agreement with previous studies, overexpression of PSD-95 greatly increased AMPAR-mediated EPSCs in wild-type CA1 neurons (Fig. 5A). Strikingly, however, overexpression of PSD-95 in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons had no effect on AMPAR currents (Fig. 5B). Under these conditions, overexpression of PSD-95 did not alter NMDAR-mediated EPSCs in wild-type or Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B and C). Because we previously showed that PSD-95 is unable to modulate AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission in Lgi1−/− neurons (29), these results indicate that the potentiation of AMPAR current after PSD-95 overexpression is totally dependent on the LGI1–ADAM22–PSD-95 linkage.

ADAM22-PDZ binding is required for PSD-95 potentiation of excitatory synapses. (A) Overexpression of PSD-95 greatly increases AMPAR-mediated EPSCs in wild-type neurons. Scatterplot of AMPAR EPSC amplitudes recorded from wild-type control and PSD-95–overexpressing neurons. (B) Overexpression of PSD-95 does not increase AMPAR-mediated EPSCs in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons. Scatterplot of AMPAR EPSC amplitudes recorded from Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 control and Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons overexpressing PSD-95. Representative traces of dual recordings are shown as Insets: bars, 50 ms and 20 pA (A and B). Bar graphs showing the normalized mean AMPAR EPSC ± SEM (A and B, Right). ***P = 0.00009, n = 8 (A); P = 0.59, n = 11 (B). (C) No difference in hippocampal LTP is observed between wild-type (black) and Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 (green) slices. P = 0.051. n.s., not significant.

How might LGI1–ADAM22 regulate PSD-95 function? We found that overexpressed PSD-95-GFP was targeted to dendritic spines and significantly increased the dendritic spine size in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons as in wild-type cultured neurons (40) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8D). However, the association of LGI1 with PSD-95-GFP clusters was significantly reduced in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons (SI Appendix, Fig. S8E). These results indicate that AMPAR potentiation and spine enlargement by PSD-95 overexpression can be dissociated and that only the former requires LGI1–ADAM22. Thus, the spine targeting of PSD-95-GFP is not sufficient for the AMPAR potentiation, and this indicates the presence of a subsequent step for PSD-95 to act on AMPARs: the precise positioning within the postsynapse instructed by LGI1–ADAM22.

Because PSD-95 overexpression mimics and occludes hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP), an activity-dependent process that involves synaptic insertion of AMPARs (41, 42), we asked whether LTP might be affected in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice. Despite reduced NMDAR function and PSD-95 dysfunction in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (Figs. 4B and 5B), no significant change in LTP induction was found between control and Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 slices (Fig. 5C).

Roles of ADAM22–PSD-95 Binding in PSD-95 Nano-Condensation and Human Epilepsy.

To define the molecular basis for ADAM22–MAGUK interaction, we crystallized the third PDZ domain of PSD-95 containing the C-terminal α-helix extension (residues R309 to S422, referred to as “PDZ3”), which was fused C-terminally with the C-terminal 15 residues of ADAM22 including a PDZ ligand (—892KKVNRQSARLWETSI906) (Fig. 6A and SI Appendix, Table S1). Following a classical mode of PDZ binding, the last four residues of ADAM22 (—903ETSI906, a canonical PDZ-binding motif) bound to the groove of PSD-95 PDZ3 (Fig. 6 B and C). Akin to the PDZ3/SynGAP complex (43), the elongated α-helix of PDZ3 may form the second binding site through the hydrophobic interaction with the side chain of L901 of ADAM22. Because the binding of SynGAP to PDZ3-SH3-GK of PSD-95 induces the dimerization or multimerization of PSD-95 and forms condensed puncta in COS-7 cells (43), and because ADAM22 binds to the same PDZ3-SH3-GK of PSD-95 (17), we tested the effect of ADAM22 binding on PSD-95 distribution in COS-7 cells. We found that, when ADAM22 and PSD-95 were coexpressed, PSD-95 made dense patches with ADAM22 at the cell surface, whereas ADAM22ΔC5 did not affect the PSD-95 distribution (Fig. 6D). Upon LGI1 coexpression, LGI1 coclustered with ADAM22 and PSD-95 at the cell surface (Fig. 6D). This coclustering activity of ADAM22 selectively depended on the PDZ3-SH3-GK domain of PSD-95, whereas SynGAP acted on either PDZ1-2 or PDZ3-SH3-GK (Fig. 6E). Furthermore, two-color STED imaging of extracellularly labeled ADAM22 and intracellular PSD-95-GFP showed their nanoscale coassemblies (∼100-nm diameter) across the plasma membrane in COS-7 cells (Fig. 6F), which mimics the relationship of ADAM22 and PSD-95 in the hippocampus (Fig. 1F). A various number of similarly sized nano-clusters of PSD-95-GFP were further assembled into larger patches/clusters (as in Fig. 6D), partly reconstituting the postsynaptic nanodomain organization. Nano-condensation of PSD-95-GFP was dependent on the ADAM22 interaction, as this was not evident in the cell transfected with ADAM22ΔC5 (Fig. 6F). These results suggest that PSD-95 is condensed locally where LGI1–ADAM22 and PSD-95 coincide within the postsynaptic nanodomain.

![Roles of ADAM22–PSD-95 binding in PSD-95 nano-condensation and human epilepsy. (A) Structure of the complex of ADAM22 PDZ ligand and PSD-95 PDZ3. The C-terminal PDZ ligand of ADAM22 (red) binds to the groove of PSD-95 PDZ3 (blue). (B and C) Close-up view of the interface between the ADAM22 C-terminal tail and PSD-95 PDZ3. The yellow represents choline, binding to the side chain of W902 of ADAM22. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines. Electron density map of the interface (2Fo-Fc map contoured at 1.0 σ level) is shown (C). (D and E) ADAM22 and PSD-95 interdependently make cell-surface clusters (D). (Scale bars: 20 μm [2 μm, magnified].) The coclustering activity of ADAM22 selectively requires the PDZ3-SH3-GK domain of PSD-95, whereas SynGAP1 acts on either the PDZ1-2 or PDZ3-SH3-GK domain (E). (F) 2C-STED imaging of extracellularly labeled ADAM22 (red) and PSD-95-GFP (green) in COS7 cells. (Inset in the Left) The image of ADAM22ΔC5-transfected cell at the same magnification as for the wild-type ADAM22-transfected cell. Dashed square area in the Left is magnified (Right). (Scale bars: 2 μm [200 nm, Right].) (G) Human epilepsy mutation of ADAM22 p.R896* causes the C-terminal 11-amino-acid deletion (ADAM22ΔC11). (H and I) ADAM22ΔC11 as well as ADAM22ΔC5 bind to LGI1 on the cell surface (H), but neither interacted with PSD-95 (I) in COS-7 cells when LGI1-FLAG or PSD-95-FLAG cotransfected with ADAM22 variants. Cell-surface bound LGI1-FLAG (red) via ADAM22 (green) was live-labeled by anti-FLAG antibody (H). Blue, nuclei labeled by Hoechst 33342. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) Arrow and arrowhead indicate the positions of immature and mature forms of ADAM22, respectively (I, Upper). The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765840310810-e51911bb-395e-4d6a-8bc7-b2da9ba0d512/assets/pnas.2022580118fig06.jpg)

Roles of ADAM22–PSD-95 binding in PSD-95 nano-condensation and human epilepsy. (A) Structure of the complex of ADAM22 PDZ ligand and PSD-95 PDZ3. The C-terminal PDZ ligand of ADAM22 (red) binds to the groove of PSD-95 PDZ3 (blue). (B and C) Close-up view of the interface between the ADAM22 C-terminal tail and PSD-95 PDZ3. The yellow represents choline, binding to the side chain of W902 of ADAM22. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines. Electron density map of the interface (2Fo-Fc map contoured at 1.0 σ level) is shown (C). (D and E) ADAM22 and PSD-95 interdependently make cell-surface clusters (D). (Scale bars: 20 μm [2 μm, magnified].) The coclustering activity of ADAM22 selectively requires the PDZ3-SH3-GK domain of PSD-95, whereas SynGAP1 acts on either the PDZ1-2 or PDZ3-SH3-GK domain (E). (F) 2C-STED imaging of extracellularly labeled ADAM22 (red) and PSD-95-GFP (green) in COS7 cells. (Inset in the Left) The image of ADAM22ΔC5-transfected cell at the same magnification as for the wild-type ADAM22-transfected cell. Dashed square area in the Left is magnified (Right). (Scale bars: 2 μm [200 nm, Right].) (G) Human epilepsy mutation of ADAM22 p.R896* causes the C-terminal 11-amino-acid deletion (ADAM22ΔC11). (H and I) ADAM22ΔC11 as well as ADAM22ΔC5 bind to LGI1 on the cell surface (H), but neither interacted with PSD-95 (I) in COS-7 cells when LGI1-FLAG or PSD-95-FLAG cotransfected with ADAM22 variants. Cell-surface bound LGI1-FLAG (red) via ADAM22 (green) was live-labeled by anti-FLAG antibody (H). Blue, nuclei labeled by Hoechst 33342. (Scale bar: 20 μm.) Arrow and arrowhead indicate the positions of immature and mature forms of ADAM22, respectively (I, Upper). The data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Recently, whole-exome sequencing analysis has begun to identify ADAM22 mutations in patients with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (19, 20). One patient had a homozygous nonsense mutation in ADAM22 (c.2686C>T, p.R896*; RefSeq ID NM_021723.3) (Fig. 6G), resulting in the ADAM22 protein lacking the C-terminal 11 amino acids (ADAM22ΔC11). We found that both ADAM22ΔC11 and ADAM22ΔC5 efficiently bound to LGI1, but did not interact with PSD-95 (Fig. 6 H and I). Thus, the human genetic evidence endorses a significant role of ADAM22–MAGUK interaction in epilepsy prevention beyond species.

Discussion

This study finds essential constituents and physiological roles of transsynaptic nanocolumns. This study defines LGI1–ADAM22, a highly conserved ligand–receptor in vertebrate brains, as a critical component in the transsynaptic nanocolumn organization together with MAGUKs. We show that disruption of the LGI1–ADAM22 linkage to MAGUKs causes transsynaptic misalignment, reduced synaptic transmission, and epileptic seizures in mice and humans. Thus, the molecular mechanism that controls transsynaptic nanoalignment has important implications for epilepsy (SI Appendix, Fig. S9).

In addition to the 2:2 LGI1–ADAM22 heterotetrameric complex for transsynaptic configuration, cryo-electron microscopic analysis shows the 3:3 LGI1–ADAM22 heterohexamer complex despite a minor pool (∼5% of the total population) (32). This 3:3 assembly mode may act in a cis-fashion and cluster Kv1 channels, for example, at the axon initial segment where LGI1–ADAM22–PSD-93/95 localizes (SI Appendix, Fig. S2D) (44). Collectively, we suggest that the LGI1–ADAM22 complex has three distinct but not mutually exclusive functions toward MAGUKs, depending on the following subcellular contexts: 1) to align pre- and postsynaptic MAGUKs as a hub in transsynaptic nanocolumns, 2) to locally condense MAGUKs as an extracellular scaffold, and 3) to activate the MAGUK’s scaffolding activity as a PDZ ligand. These modes of action of LGI1–ADAM22 help clarify previous seemingly unrelated results in the Lgi1−/− mouse: reduced synaptic AMPAR function (22, 29) and reduced axonal Kv1 channel function (31). Because both AMPAR and the Kv1 channel are commonly anchored by MAGUKs, misregulated MAGUKs could decrease AMPAR and Kv1 channel functions.

The molecular identities that constitute the transsynaptic nanocolumn architecture remain incompletely understood. Neurexin–Neuroligin is a representative candidate, which binds to CASK and PSD-95, respectively (11). Consistently, disruption of Neuroligin–PSD-95 interaction by the C-terminal peptide of Neuroligin impairs pre- and postsynaptic alignment and decreases AMPAR-mediated synaptic transmission in cultured hippocampal neurons (7). Interestingly, both Neuroligin and ADAM22 bind to the third PDZ domain on PSD-95. This suggests that Neurexin–Neuroligin and LGI1–ADAM22 may have a common function in transsynaptic nanocolumns. However, genetic evidence that loss-of-function of either LGI1 or ADAM22 causes epilepsy (212223–24) while mutations of either Neuroligin or Neurexin associate with autism (11) does not necessarily support their common redundant function in vivo. Whether LGI1–ADAM22 and Neurexin–Neuroligin function in different cellular contexts or mediate distinct functions will require future studies.

The concept of the extracellular scaffold, in which extracellular proteins facilitate the clustering of certain receptors at the synapse, has recently gained considerable attention. Caenorhabditis elegans LEV-9, a secreted protein, and LEV-10, a transmembrane protein, interact directly with acetylcholine receptors and ensure the receptor clustering (45). The secreted Cbln-mediated ternary complex (e.g., Neurexin–Cbln1–GluD) is another example that promotes and maintains synapse formation (1314–15). In both cases, the extracellular direct interactions with the receptor play a central role in the receptor accumulation. In contrast, the LGI1–ADAM22 complex does not directly associate with glutamate receptors or Kv1 channels and requires intracellular scaffolds (MAGUKs) to regulate glutamate receptors and Kv1. LGI1–ADAM22 determines the precise location of PSD-95 in the synapse, and, in turn, PSD-95 could stabilize LGI1–ADAM22 around the synapse (SI Appendix, Fig. S8E). Such an interdependent synaptic localization between LGI1 and PSD-95 (i.e., coordination between extracellular and intracellular scaffolds) would reinforce the precise receptor clustering.

Recent studies show that the C-terminal PDZ ligand of SynGAP induces multimerization and phase transition of MAGUKs via PDZ-SH3-GK tandems (43, 46). In addition, the PDZ ligand and Arg-rich motif of TARPs trigger phase transition of MAGUKs (47). Given that ADAM22 and Neuroligin possess a Arg/Lys-rich motif upstream of the C-terminal PDZ ligand, it might be worthwhile to examine whether ADAM22 and/or Neuroligin cause molecular condensation of MAGUKs via phase separation. At the same time, the PDZ ligand binding may regulate the scaffolding activity of MAGUKs. Given that overexpressed PSD-95 increases AMPAR-medicated synaptic transmission in wild-type neurons, but not in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons (Fig. 5 A and B), the PDZ ligand of ADAM22 may have an allosteric effect. The ADAM22 binding may unfold the whole PSD-95 protein structure so that the N-terminal two PDZ domains (PDZ1 and PDZ2) become accessible to many membrane proteins, while the SH3-GK domain is released to make intermolecular assemblies (46, 48). These mechanisms would amplify the size and complexity of PSD-95–based protein complexes and explain how ADAM22 regulates the synaptic condensation of PSD-95 that outnumbers ADAM22. Future studies are required to clarify whether ADAM22 is the modulatory trigger protein in this model.

Our structural analysis unexpectedly showed that choline derived from a crystallization buffer binds to the side chain of W902 of ADAM22 (Fig. 6 B and C), implying the possible association of the ADAM22–PSD-95 PDZ3 region with phosphatidylcholine at the cytoplasmic leaflet face of the plasma membrane. This may allow closer association between the cytoplasmic tail of ADAM22 and the plasma membrane and lead to a conformational change of PSD-95 from its perpendicular orientation (49) to a parallel orientation toward the plasma membrane. To biochemically examine the allosteric effect of ADAM22 binding, we compared the PSD-95 interactome between wild-type and Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice and found that the Kv1 channels associated with PSD-95 were greatly reduced in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E).

The PSD centric model is one of the most attractive molecular mechanisms for LTP (50, 51). Under resting conditions, there are about 200 to 300 PSD-95 and 50 AMPAR molecules in one PSD. Here, the key interaction occurs between TARPs and PSD-95 for synaptic capturing of AMPARs. Based on this model, a population of synaptic PSD-95 molecules is masked and AMPAR–TARP cannot bind to them. Upon LTP stimulation, some PSD-95 molecules become unmasked and AMPAR–TARP binds to them. When PSD-95 is overexpressed, they outnumber any masking proteins so AMPAR–TARP can bind to unmasked PSD-95. Thus, LTP expression and PSD-95 overexpression are assumed to accomplish the same thing—an increase in the number of unmasked PSD-95. Unexpectedly, we found that LTP occurs in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 slices (Fig. 5C), whereas PSD-95 overexpression does not increase AMPAR currents in Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 neurons (Fig. 5B). The dissociation of the PSD-95 enhancement from the LTP does not match the present PSD centric model. An interesting possibility is that other MAGUKs, such as PSD-93 and SAP102, may redundantly circumvent the requirement for PSD-95 through molecules besides ADAM22.

The Adam22−/− or Lgi1−/− mouse displays a remarkably stereotyped pattern of epileptic seizures and premature death during the weaning period, whereas the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse shows epilepsy at a later stage and unprovokedly dies around 2 to 8 mo of age. The unpredicted, repetitive seizure phenotype in the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse fits with the nature of epilepsy in human patients. Therefore, the Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mouse provides an ideal model to elucidate pathogenesis and therapeutics for human epilepsy. In addition, reinforcement of the transsynaptic LGI1–ADAM22–PSD-95 MAGUK linkage represents an intriguing therapeutic target for human epilepsy.

Materials and Methods

Antibodies and Plasmid Constructions.

The antibodies used in this study and the plasmids for protein expression of LGI1, ADAM22, and PSD-95 are described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Animal Experiments.

All animal studies were reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at the National Institutes of Natural Sciences (NINS) and were performed according to their institutional guidelines concerning the care and handling of experimental animals and also conducted according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines at the University of California, San Francisco. Mouse strains used in this study include the following: Adam22FAH/FAH knock-in mouse, Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 knock-in mouse, Lgi1 knockout mouse (22), C57BL/6N mice, and B6D2F1 female mice (Japan SLC). The Adam22FAH/FAH knock-in and Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 knock-in mice were generated using the CRISPR/Cas9 method. Detailed methods are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Biochemical Analysis.

Detailed methods for immunoaffinity purification of ADAM22-FAH, mass spectrometry analysis, pull-down assay, Western blotting, and BN-PAGE are described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Surgery and Video-EEG/LFP Recordings.

Eight (seven male and one female) Adam22ΔC5/ΔC5 mice and one female wild-type littermate were used for simultaneous recordings of behaviors and EEGs or LFPs (video-EEG/LFP recording). Detailed methods are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Histological and Cell Biological Analysis.

Detailed methods for immunohistochemical and immunohistofluorescence staining of brain sections, immunocytofluorescence staining of mouse hippocampal neuron culture, and cell-surface staining of COS-7 cells are described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

STED Superresolution Imaging and Image Analysis.

Immunohistofluorescence staining of fresh-frozen mouse brain sections was performed. For two-color STED imaging with a 660-nm depletion laser, Alexa Fluor 488- and 555-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used. Gated STED imaging was performed using the Leica TCS SP8 gated STED superresolution system combined with Leica HyD detectors (supported by Exploratory Research Center on Life and Living Systems). To measure the nearest neighbor distance between RIM2- and PSD-95 nanodomains, intensity line profiles were drawn across the highest peaks of apposed RIM2 and PSD-95 clusters within synapses in side view, and the peak distance was determined using LAS X software (Leica). Data with a <50-nm distance (corresponding to synapses in face view) or a >250-nm distance (no synaptic apposition) were excluded. Additional details are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Slice Culture Preparation, Transfection, and Electrophysiology.

All datasets include recordings from at least seven hippocampal slices from three different animals. Hippocampal slice cultures were prepared from 7- to 10-d-old mice. At 4 days in vitro (DIV), for overexpression experiments, slice cultures were transfected using a Helios Gene Gun (BioRad). Recordings were made at DIV 8 to 10. Transfected pyramidal cells were identified using fluorescence microscopy. In all paired experiments, transfected and neighboring control neurons were recorded simultaneously. For two-way statistical comparisons, Student’s t test was used.

For LTP recording, 300-μm transverse acute slices were cut from P18 to P26 mice with a Leica vibratome. LTP was induced by stimulating Schaffer collateral axons at 2 Hz for 90 s while clamping the cell at 0 mV after recording at least a 3-min baseline. Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparing two different LTP groups. Additional details are in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Crystallography of PSD-95 PDZ3–ADAM22C.

Detailed methods for protein expression, purification, crystallization, and structure determination of rat PSD-95 PDZ3 (residues 309 to 422; NP_062567.1) C-terminally fused with a Gly-Ser-Ser-Gly linker and the C-terminal 15 residues of human ADAM22 (ADAM22C; residues 892 to 906; NP_068369.1) are described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analysis.

To perform statistical analysis, at least three independent tissue samples from at least three animal pairs were included in the analyses (except for Fig. 1F). Results are shown as means ± SEM or medians with interquartile ranges. Statistical details of individual experiments are described in figure legends or SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Keiji Imoto (NINS) and Dr. Ryuichi Shigemoto (Institute of Science and Technology, Austria) for helpful discussions and suggestions; Ms. Yumiko Makino (Functional Genomics Facility, National Institute for Basic Biology Core Research Facilities) for technical assistance; and members of the M.F. and R.A.N. laboratories for support. This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Grants 19H03331 and 19K22439 (to Y.F.), Grant 19H03162 (to A.Y.), Grant 15H05873 (to A.N.), Grant 18H03983 (to S.F.), and Grants 19H04974, 19K22548, 20H04915, and 20H00459 (to M.F.); Daiko Foundation (Y.F.); NIH Grant R01MH117139 (to R.A.N.); and the Hori Sciences and Arts Foundation (M.F.).

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and supporting information. The coordinates and structure factors of the PSD-95-PDZ3–ADAM22 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under the accession code 7CQF.

References

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

LGI1–ADAM22–MAGUK configures transsynaptic nanoalignment for synaptic transmission and epilepsy prevention

LGI1–ADAM22–MAGUK configures transsynaptic nanoalignment for synaptic transmission and epilepsy prevention