- Altmetric

The interaction between different types of wave excitation in hybrid systems is usually anisotropic. Magnetoelastic coupling between surface acoustic waves and spin waves strongly depends on the direction of the external magnetic field. However, in the present study we observe that even if the orientation of the field is supportive for the coupling, the magnetoelastic interaction can be significantly reduced for surface acoustic waves with a particular profile in the direction normal to the surface at distances much smaller than the wavelength. We use Brillouin light scattering for the investigation of thermally excited phonons and magnons in a magnetostrictive CoFeB/Au multilayer deposited on a Si substrate. The experimental data are interpreted on the basis of a linearized model of interaction between surface acoustic waves and spin waves.

Studies of the coupling of elastic waves with other wave excitations, including spin waves, in nanostructures are experiencing a revival, which is mostly due to the progress in experimental techniques.1−12 Magnetostrictive systems are promising for switching the magnetic configuration and controlling spin-wave propagation by nonmagnetic means.5,13−15 The strategy to use strain (elastic waves) or an electric field (electromagnetic waves) is technically less problematic than controlling the magnetic system by magnetic field for the realization of logic gates,5 magnetic recording,13 or signal processing.16,17 The combined impact of elastic deformation and electric field on magnetization dynamics can be used in cavity magnonics18 to realize quantum information processing.

The mechanism of magnetoelastic interaction is complex and difficult to understand. An efficient way to get an insight into it is to first consider the simplest structures, which constitute a platform for more sophisticated magnetoelastic nanodevices. Here, we consider the generic structure, a magnetostrictive layer deposited on a nonmagnetic substrate, with the magnetization dynamics in the layer coupled to the elastic excitations concentrated on the surface of the structure.

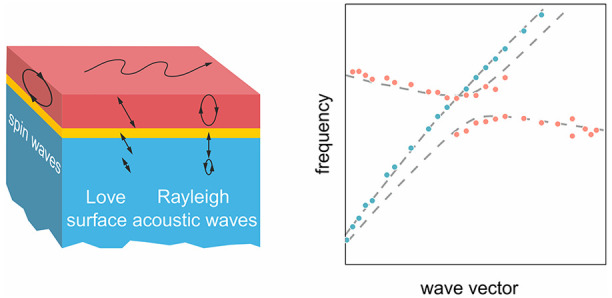

For propagating waves the coupling is known to require the matching of both the frequencies and the wavelengths.19 This condition can be fulfilled for spin waves (SWs)20,21 and surface acoustic waves (SAWs)22,23 existing in the same range of frequencies and wave vectors. However, the strength of the magnetoelastic interaction depends on the orientation of the wave vector with respect to the direction of the static magnetic field. Moreover, this interaction is different for different types of SAWs, specifically, Rayleigh-SAWs (R-SAWs) and Love-SAWs (L-SAWs), which differ in the orientation of dynamic component displacement. Thus, the coupling is strongly anisotropic4,24 and cannot be observed for arbitrary SAWs and SWs, even if their frequencies and wave vectors match.

Another fundamental limiting factor is the cross-section of the SAWs and SWs. Although the profiles of SAWs and SWs can relatively easily agree in the in-plane direction, which is ensured by the wave-vector matching, the net interaction can be minimized or even suppressed for some particular profiles in the out-of-plane direction. The role of the latter factor is not fully recognized in the scientific community.

Using finite element calculations based on a theoretical model (see Supporting Information for details), we interpret our Brillouin light scattering (BLS) experimental data concerning the magnetoelastic dispersion relation of thermally excited SAWs and SWs.25,26 To explain the existence (or absence) of magnetoelastic interaction, manifested as anticrossings of magnonic and phononic dispersion branches, we need to take into account not only the anisotropy of the interaction but also the profiles of the SAWs and SWs in the direction normal to the surface. We report the observation of magnetoelastic interaction between L-SAWs and SWs for the backward volume geometry (wave vector parallel to the static magnetic field), in which the coupling between R-SAWs and SWs is weak because of the anisotropy of this interaction. Finally, we show that the lack of expected interaction between R-SAWs and SWs for the oblique geometry (field at 45° with respect to the direction of the wave vector) can only be explained based on the spatial distribution of the displacement (and the related strain) within the magnetic layer. Our results demonstrate an interplay between the anisotropy of interaction and the spatial cross-section of excitations of both types.

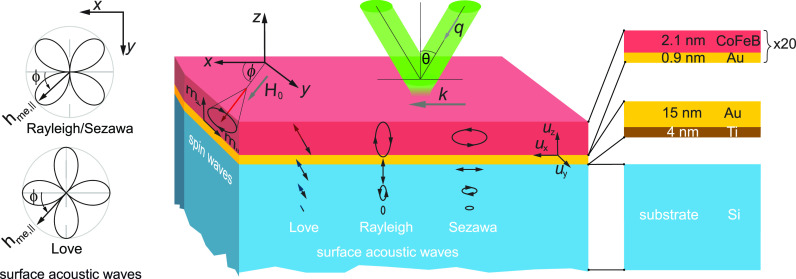

The considered system, presented in Figure 1, consists of a magnetostrictive CoFeB(2.1 nm)/Au(0.9 nm)x20 multilayer deposited on a thick nonmagnetic Si substrate with an Au(15 nm)/Ti(4 nm) buffer bilayer (see Supporting Information for details). The multilayer has an in-plane-oriented saturation magnetization ensured by the sufficient thickness of the CoFeB layers.27 For the fundamental spin-wave (F-SW) mode and the lowest perpendicularly standing spin waves (PS-SWs),20,28 the multilayer can be regarded as an effective medium of reduced magnetization (due to the surface anisotropy at the Au/CoFeB interface) gained at the expense of a slight increase in the spin-wave damping.27 The SWs are confined to the magnetic part of the multilayer and precess with in-plane and out-of-plane components of magnetization, m∥ and m⊥, respectively. The orientation of m∥ can be changed with the direction ϕ of the external field H0. The orientation of the plane of incidence and the angle of incidence θ in Brillouin light scattering (BLS) measurements determine the direction and magnitude of the wave vector k for the SAWs and SWs observed in the experiment (in our study the wave-vector direction is fixed, k = kx̂).

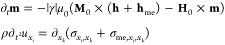

In the studied system acoustic waves propagate along the surface of the silicon substrate and are mostly concentrated in the CoFeB/Au multilayer cover. The multilayer can be regarded as an effective magnetostrictive medium where surface acoustic waves can interact with spin waves. The frequencies of phonons and magnons are determined by Brillouin light scattering (BLS) for selected wave vectors k = q sin θ, where q is the wave vector of the incident light. The magnetoelastic interaction is strongly anisotropic. The magnetoelastic field perceived by a spin wave depends on the orientation of the wave vector k with respect to the direction of the applied field H0. This anisotropy is different for Love and Rayleigh/Sezawa acoustic waves; presented on the left are the respective polar plots of the in-plane component of magnetoelastic field. The strength of the interaction is also related to the profiles of the acoustic waves and spin waves across the thickness of the magnetostrictive multilayer.

Potentially, three types of SAWs can be observed, with a different polarization of the displacement, i.e., R-SAWs and S-SAWs (with elliptical polarization of the displacement ux/|ux| = ±iuz/|uz|) and L-SAWs (transfers with linearly polarized component uy). The strength of the magnetoelastic interaction depends on the direction of the external magnetic field and is different for different types (polarization) of SAWs. Shown in Figure 1, the angular plots of the magnetoelastic field magnitude have lobes at ϕ = 0° or ϕ = 45° for L-SAWs and R-/S-SAWs, respectively; this illustrates the differences in anisotropy of the SAW/SW interaction.

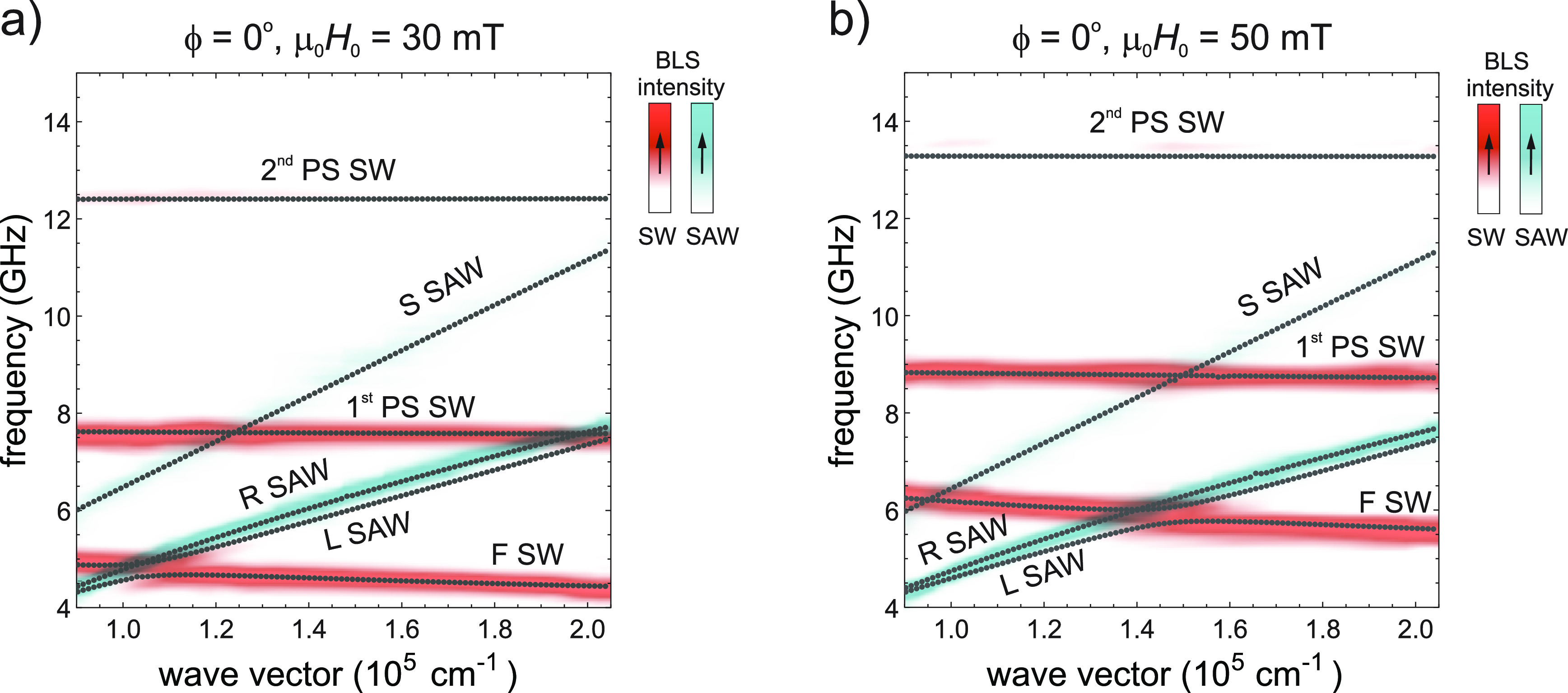

A magnetic field of appropriate magnitude is necessary for interaction between SWs and SAWs to occur in the wave-vector range accessible for BLS. An increase in the magnetic field pushes up the SW frequencies, while the SAW frequencies remain unaffected. As a result, the (anti)crossings between magnonic and phononic dispersion branches f(k) are shifted toward larger values of wave vector k.

Figure 2 shows the experimental and theoretical magnetoelastic dispersion relations in the system presented in Figure 1 for two different values of the magnetic field applied along the direction of the wave vector k, i.e., for backward volume geometry. As a result of increasing the field from 30 mT (Figure 2a) to 50 mT (Figure 2b), the crossing of the fundamental spin-wave (F-SW) mode shifts up; see also the plot in Figure 3. Figure 2 presents BLS spectrum sweeps for successive wave-vector values in the form of maps where the color intensity represents the BLS intensity. The blue-red lines in the frequency and wave-vector domain are the experimental magnetoelastic dispersion branches. The spectra of phonons (blue lines) and magnons (red lines) are measured separately (see Supporting Information) and then superimposed in one plot. The experimental data are supplemented by the results of finite element method calculations (see Supporting Information). The calculated dispersion relations are plotted as dotted lines. The dispersion branches are identified as those of SAWs or SWs of specific types by the inspection of numerically calculated profiles of the dynamic displacement and magnetization. A striking finding is the lack of an L-SAW branch in the experimental data, except for a interaction region (anticrossing) with the F-SW branch, observed just below the R-SAW branch. This anticrossing cannot be identified as R-SAW/F-SW interaction, as it is observed clearly below the high-intensity R-SAW dispersion branch. Moreover, the theory does not predict R-SAW/F-SW interaction for the magnetic field applied along the direction of the wave vector (for ϕ = 0, i.e., for the backward volume geometry for SWs).

BLS experimental magnetoelastic dispersion relation measured for magnons (red lines) and phonons (blue lines) with an in-plane applied magnetic field of (a) 30 mT and (b) 50 mT; the color intensity represents BLS intensity. The increase in the magnetic field affects only the magnonic branches of dispersion by shifting them up. The modes are identified with the aid of numerical calculations (gray points). For the considered backward volume geometry (k ∥ H0, ϕ = 0) we observe the fundamental spin-wave mode (F-SW) and the two first perpendicularly standing spin waves (PS-SW). Among the elastic waves we identify Rayleigh and Sezawa surface acoustic waves (R-SAW and S-SAW, respectively). A Love surface acoustic wave (L-SAW) is barely visible in the experimental plot and is detectable mostly due to its interaction with F SW. Note that we do not observe any other interaction between elastic and magnetic modes in this system for ϕ = 0.

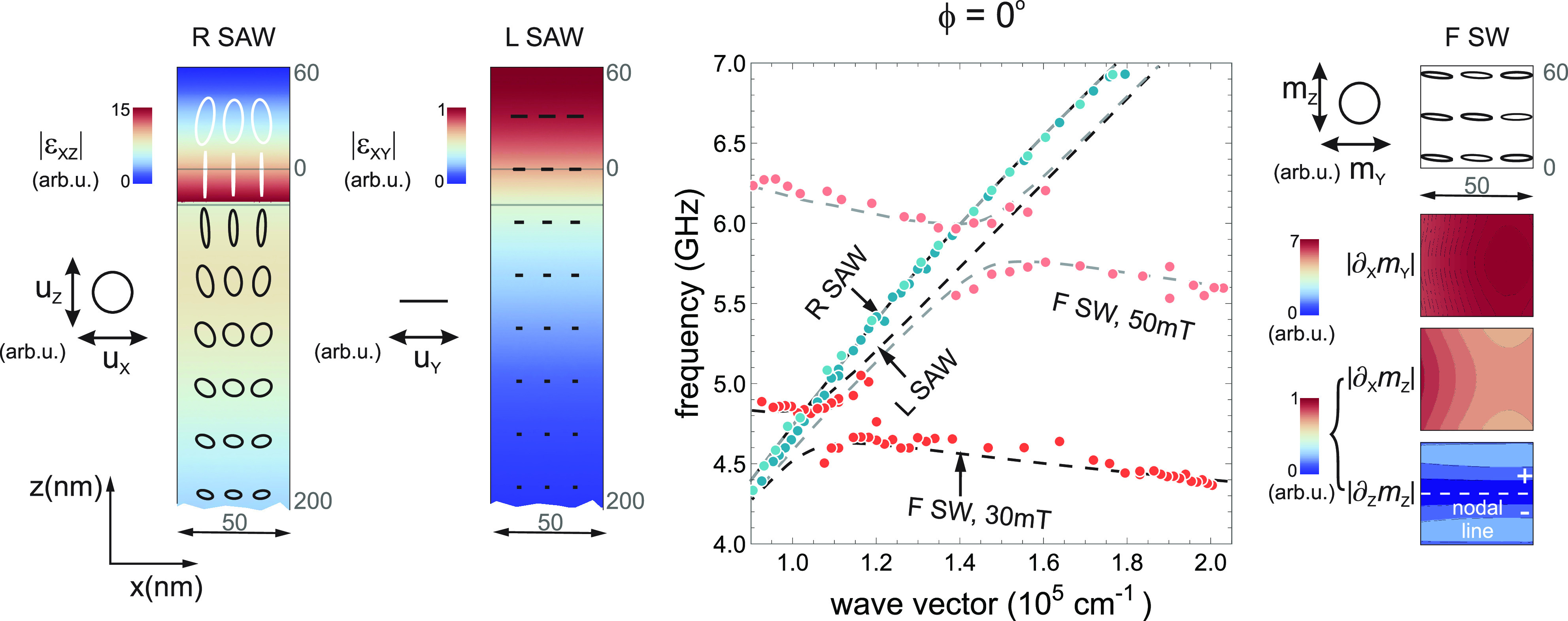

Interaction between the L-SAW and the F-SW modes for ϕ = 0, manifested as the anticrossing of the respective dispersion branches, observed both experimentally (points in the plot corresponding to the maximums of the BLS lines) and in numerical calculations (dashed lines). The stronger L-SAW/F-SW and weaker R-SAW/F-SW interactions can be explained by referring to the anisotropy of the magnetoelastic interaction and taking into account the spatial distribution of the strain tensor and the spatial derivatives of the dynamic components of magnetization, represented by the color maps (region 0 > z > 60 nm corresponds to the magnetostrictive multilayer). The elliptical loops (for R-SAW and F-SW) and horizontal lines (for L-SAW) show the variation of the SAW and SW amplitudes, with opposite directions of gyration marked white or black.

The details and mechanism of this interaction are presented in Figure 3. The main plots show the anticrossing of the F-SW mode with the R-SAW and L-SAW for two external field values, 30 mT and 50 mT, in the backward volume geometry. Indicating the frequencies that correspond to the maximums of the BLS peaks for successive wave-vector values, the experimental results (points) are distributed quite precisely along the numerical dispersion (dashed lines). By comparing the experimental and numerical data we can attribute with certainty the approximately observed anticrossing to the interaction between the L-SAW and the F-SW. Note that the L-SAW is barely visible in the BLS measurements beyond the anticrossing region (this type of SAW must be measured for cross-polarized incident and refracted beams, which gives a much weaker BLS signal).

The full width at half width of magnonic BLS peaks (fwhm ≈ 0.4 GHz) is slightly larger than the frequency splitting at the F-SW/L-SAW anticrossing (Δf ≈ 0.25 GHz), which still allows for resolving them in the spectrum (see Supporting Information). The measured phonons are damped with a similar rate (fwhm ≈ 0.3 GHz for R-SAW, close to F-SW/L-SAW anticrossing). Taking this value as an upper bound of FWHW for L-SAW peak (invisible in our spectra), we can estimate the cooperativity of F-SW/L-SAW interaction as C = Δf2/FWHW2 ≈ 0.4 < 1, which demonstrates that the considered magnon–phonon coupling is relatively weak.

The interaction between SAWs and SWs can be analyzed by considering the magnetoelastic components of the effective field hme and the stress tensor σme in the Landau–Lifshitz equation coupled to the elastodynamic equation20,29,30

Figure 3 presents color maps of the discussed components of the stress tensor (left columns) for the R-SAW and L-SAW and the derivatives of the dynamic components of the magnetization (right column) for the F-SW. The L-SAW/F-SW interaction results from the large εx,y value and the significant values of ∂xmy in the magnetic multilayer (0 < z < 60 nm). For R-SAW and F-SW the parameters εx,z, ∂xmz, and ∂zmz in the magnetic multilayer are substantially smaller. The profiles of the L-SAW and F-SW do not change significantly due to the interaction, except for the phase flip between higher and lower breach at anticrossing.

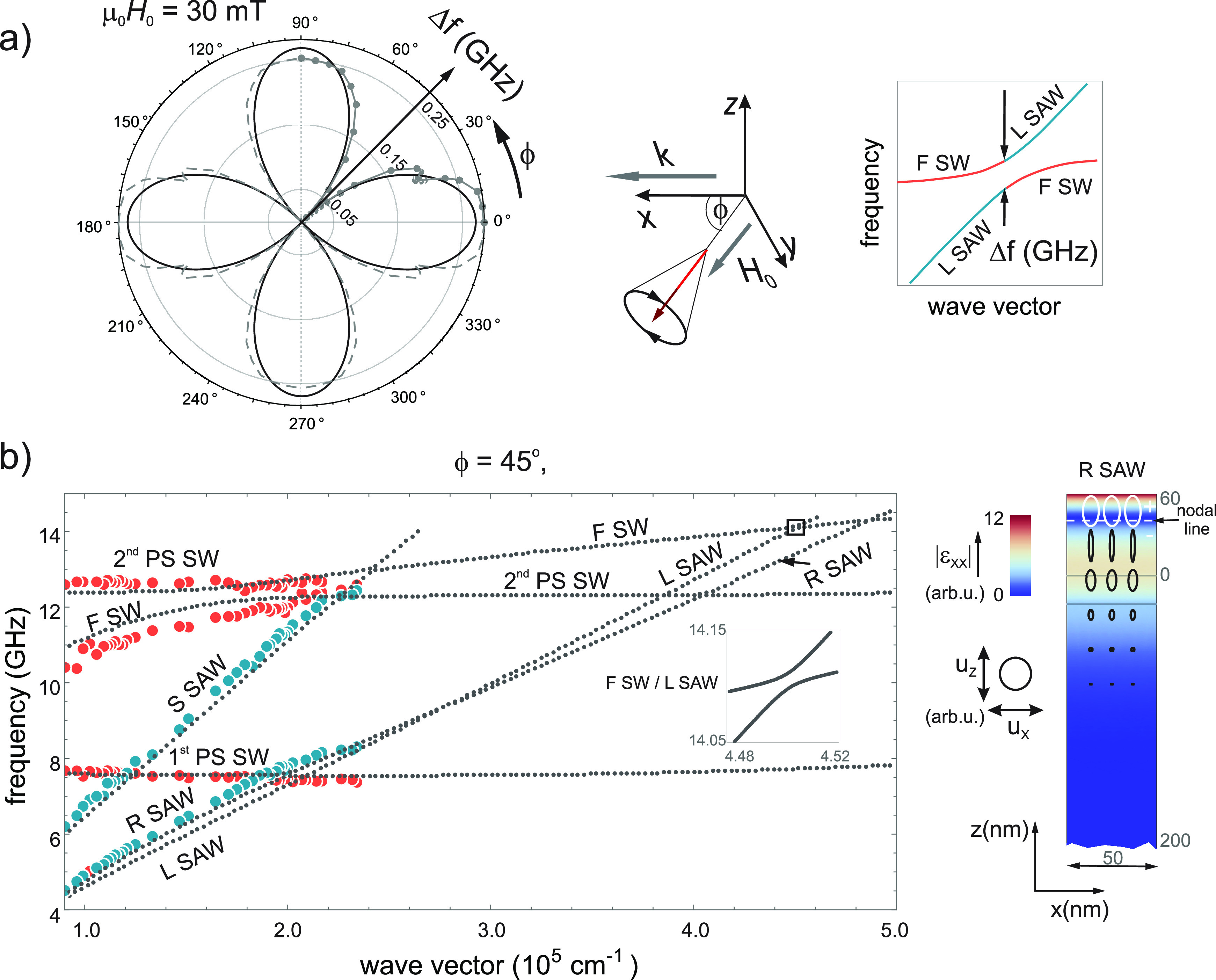

Let us discuss how the L-SAW/F-SW and R-SAW/F-SW interactions vary with changing direction of the magnetic field with respect to the wave vector (oriented along the x-direction). Figure 4(b) shows the magnetoelastic dispersion relation for the oblique orientation of the magnetic field (ϕ = 45°). The dispersion is plotted in the same frequency range as in Figure 3, but the wave-vector range had to be extended to find the crossing of F-SW with L-SAW and R-SAW because of a significantly changed slope of the F-SW dispersion branch.28

(a) The frequency splitting at the L-SAW/F-SW anticrossing as a function of the angle ϕ between the external field H0 and the wave vector k. The numerical Δf(ϕ) dependence (gray points in the polar plot) is qualitatively the same as the dependence of the in-plane component of the magnetoelastic field generated by the L-SAW: hme,∥ ∝ cos(2ϕ) (black line in the polar plot). (b) At ϕ = 45° hme,∥ = 0 for the L-SAW, and the frequency splitting for the L-SAW/F-SW anticrossing is practically reduced to zero (see the inset). Note that we also observe the lack of R-SAW/F-SW interaction, which cannot be explained based on the interaction anisotropy (see hme,∥(ϕ) for R-SAW in Figure 1). The R-SAW/F-SW interaction is suppressed to zero due to the presence of a nodal line for the xx component of the strain tensor, which averages to zero the magnetoelastic coupling (see the color map).

Both the L-SAW/F-SW and R-SAW/F-SW couplings are practically negligible. This is not surprising as far as the L-SAW/F-SW coupling is concerned, since in this case the in-plane component of the magnetoelastic field hme,∥ ∝ εxy cos 2ϕ = 0 (for ϕ = 45°) and the out-of-plane component hme,⊥ ∝ εyz sin ϕ are very small (εyz ≪εxy ∝ k, for 1/k much smaller than the thickness of the magnetic multilayer); (see the Supporting Information for details). This effect of angular dependence of the L-SAW/F-SW coupling is illustrated in Figure 4(a) by a polar plot of the frequency splitting Δf(ϕ) at the anticrossing of the L-SAW and F-SW dispersion branches superimposed on the hme,∥(ϕ) dependence. The good match between these two polar plots (Δf(ϕ) ∝ hme,∥(ϕ)) confirms that the strong reduction of the frequency splitting at ϕ = 45° is solely related to the anisotropy of magnetoelastic interaction (i.e., to the relative orientation of the wave vector and the external magnetic field).

A similar reasoning based on the anisotropy of magnetoelastic coupling would lead to the prediction of a R-SAW/F-SW anticrossing, since hme,∥ ∝ εxx sin 2ϕ ∝ k sin 2ϕ is maximal for ϕ = 45° and has significant values for larger k. However, this expectation is not confirmed in our study; the R-SAW/F-SW anticrossing is hardly observed (Δf ≈ 0). To explain this result we must analyze the SAW profile in the direction normal to the surface. For R-SAW the tangential component of the displacement ux flips phase in the normal direction (z-direction), see Figure 1. For the considered structure we observe a nodal line for ux and the related component of the strain tensor εxx within the magnetic multilayer. As a result the tangential component of the magnetoelastic field hme,∥ ∝ εxx = ikux is close to zero.

We have shown that not only the anisotropy of magnetoelastic interaction (related to the orientation of the magnetic field) but also the SAW profile within the magnetostrictive layer is of importance for the observation of coupling between SWs and SAWs. For R-SAWs the tangential component of displacement ux can have nodes within the magnetic layer, resulting in a reduction of the net strength of magnetoelastic interaction even if the strain εxx is locally significant. A similar effect is expected for S-SAWs, where uz flips phase in the normal direction. In an L-SAW the displacement uy does not have any nodes (uy changes monotonously in the normal direction). It is worthy of notice that the spatial changes in the SAW profile (e.g., the distance of the node from the surface) are small compared to the wavelength λ = 2π/k. The location of R/S-SAW nodes depends on elastic properties of the system, specifically, the elastic material parameters of the multilayer and the substrate, and the thickness of the multilayer.

Our study reveals an additional factor limiting the interaction between surface acoustic waves and spin waves. The SAW/SW coupling proves to require an appropriate profile of the elastic wave near the surface of the magnetostrictve structure, at distances much smaller than the wavelength. We have shown that this additional factor plays a role for some types of surface acoustic waves (Rayleigh and Sezawa waves), while other types (Love waves) are insensitive to it. We believe that the studies on magnon–phonon interaction in confined geometries (surfaces, cavities) are very promising and can reveal unusual interaction mechanisms similar to those found between cavity photons and magnons.31

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c03692.

Preparation of the sample and material parameters, experimental setup, theoretical model, and numerical simulations (PDF)

Author Contributions

H.G. fabricated the sample. N.K.P.B, M.Z., A.T., and S. Miel. carried out the BLS measurements. P.G., G.C., S. Mies., and J.W.K. developed the theoretical model and performed numerical simulations. All the authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding, hereby gratefully acknowledged, from the National Science Centre, Poland, project no. UMO-2016/21/B/ST3/00452. S. Mies. would like to additionally acknowledge the financial support from the National Science Centre, Poland, project no. UMO-2020/36/T/ST3/00542. The authors thank Prof. M. Krawczyk for fruitful discussion and useful comments and Dr. O. Chumak for the determination of magnetoelastic coupling constants.

The Interaction

between Surface Acoustic Waves and

Spin Waves: The Role of Anisotropy and Spatial Profiles of the Modes

The Interaction

between Surface Acoustic Waves and

Spin Waves: The Role of Anisotropy and Spatial Profiles of the Modes