While great advances have been made in understanding the pairing mechanism in cuprates, a coherent description of the normal-state phenomenology, including the pseudogap and the strange metal phase, remains elusive despite over three decades of intense research (, ). The existence of charge order (refs. 4567– and references therein) and small Fermi surface pockets (1011121314–) is now established in the underdoped regime but a consensus on the underlying electronic ground state has not yet been reached. A longstanding issue is the extent of the regime in which fluctuating superconductivity without phase coherence persists, both in temperature () and in magnetic field (H), and the corresponding magnitude of the upper critical field (Hc2). For example, a widely varying Hc2 has been reported for archetypal cuprates at hole doping p≈0.12, ranging from 24 T for YBa2Cu3O6+x (Y123) () to 70 T for La2−xSrxCuO4 (LSCO) () and Bi2Sr2−xLaxCuO6+δ (Bi2201) (). Consequently, two fundamentally different H−T phase diagrams have been proposed: one featuring a convergence of the irreversibility line and Hc2 at zero field and temperature and the other featuring a (quantum) vortex liquid regime extending far beyond the irreversibility line. Identifying a unified picture for the H−T phase diagram in underdoped cuprates thus represents an important outstanding challenge.

Recently, a signature of bulk superconductivity has been observed in Y123 at p≈ 0.11 up to 45 T, namely a small yet finite magnetic hysteresis induced by vortex pinning (, ) and a zero-resistivity state when a vanishingly small excitation current is used (). These results suggest the existence of a second vortex-solid regime that is highly susceptible to external perturbations with a markedly reduced critical current density jc in the T→0 limit. The nonstoichiometric nature of underdoped Y123, however, presents a caveat for the experimental interpretation and a possible influence of doping and/or chemical inhomogeneity is difficult to eliminate. Besides, the intense magnetic field required to suppress superconductivity in Y123 limits the feasibility to study the low-temperature electronic transport outside the p≈ 0.11 regime. Therefore, the doping range in which such low-jc superconductivity occurs remains largely unexplored.

To investigate whether this unconventional low-T vortex phase is unique to Y123 at a specific doping level or generic to the underdoped cuprates, we have studied three other cuprate families−YBa2Cu4O8 (Y124), LSCO, and Bi2201−with distinctly different Tc values, crystal structures, and levels of disorder. Y124 is the stoichiometric analogue of Y123 with a fixed p = 0.14 and Tc = 78 K. Without the extrinsic doping typically required for high-Tc superconductivity, Y124 has an exceptionally high level of electronic homogeneity as evidenced by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and quantum oscillation measurements (, , ). In contrast, LSCO and Bi2201 have a lower Tc< 40 K and are more electronically disordered. Nevertheless, LSCO and Bi2201 cover a wide doping range spanning the entire superconducting dome. Here, we study the in-plane electrical resistivity under continuous magnetic fields up to 45 T and temperatures down to 0.32 K, over three decades of excitation current 1 μA ⩽I⩽ 3 mA and across a wide doping range 0.085 ⩽p⩽ 0.23. We find that nonohmic resistivity is observed in those compounds only where long-range charge order emerges under intense magnetic field, thereby resulting in a fragile superconducting state with a suppressed critical current density jc. This anomalous vortex liquid is found to persist up to the highest accessible magnetic-field scale, implying the existence of a quantum vortex liquid in the T→0 limit. Importantly, this work suggests that, at high field, the intricate interplay between charge order and superconductivity leads to the emergence of a microscopically intertwined state with spatially varying order parameters, such as fragile superconductivity () and/or pair-density-wave state (), which is crucial for the understanding of the low-T electronic ground state of underdoped cuprates.

Charge Order in High-Tc Cuprates

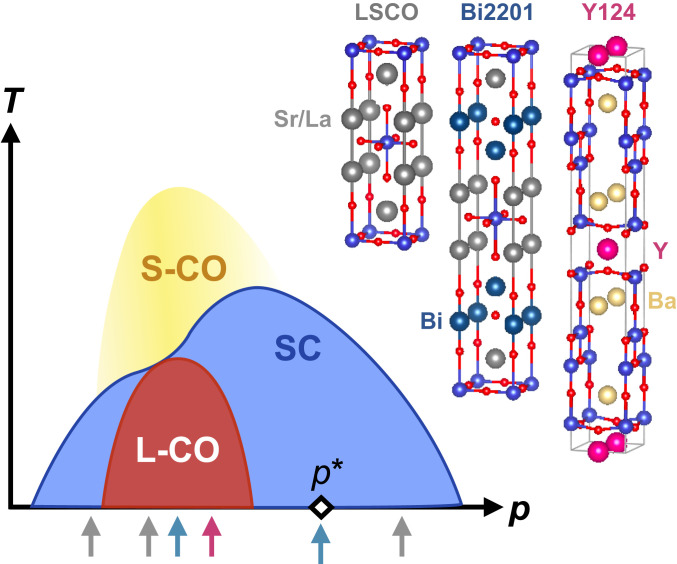

The T−p phase diagram of hole-doped cuprates across the superconducting dome is illustrated schematically in Fig. 1. Two forms of charge order have previously been observed in underdoped Y123, LSCO, and Bi2201 by a variety of experimental probes (45–, 2627282930–). The first one, found in zero applied magnetic field, has short-range correlations within the CuO2 plane (45–) and weak antiphase correlations along the c axis (). Recent resonant X-ray scattering experiments (, ) report that this short-range charge order persists in overdoped LSCO and Bi2201 (up to p≈ 0.23). A second, related type of charge order, with a longer in-plane correlation length and in-phase c-axis correlations, has been found in a large magnetic field (26272829–). There is strong evidence from NMR (29) for magnetic-field–induced long-range charger order within the underdoped regime 0.09≲p≲0.16 in the cuprate families studied here. In LSCO, stripe order−interlocked charge and spin order−is present in the underdoped regime p≈ 0.12 and found to be strongly enhanced by a moderate magnetic field (, ). Despite the lack of direct evidence, the presence of charge order in Y124 has been inferred from the existence of a small electron pocket (, , ) for which charge order of sufficiently long range is believed to be responsible ().

Fig. 1.

Temperature–doping phase diagram of superconducting cuprates. Charge order with short-range in-plane correlations (S-CO) at zero magnetic field (45–, , ) and long-range three-dimensional correlations (L-CO) at high magnetic field (2627282930–) is found to onset at temperatures indicated by the dome-shaped shades peaked at p≈0.12. L-CO are found to occur for 0.09 ≲p≲0.16, while recent X-ray scattering experiments (, ) have found signatures of S-CO in overdoped Bi2201 and LSCO up to p≈ 0.23. Vertical arrows underneath the dome of superconductivity (SC) mark the doping levels of the three different cuprate families studied in this work, whose crystal structures are labeled by corresponding colors.

Onset of Nonohmic Resistivity

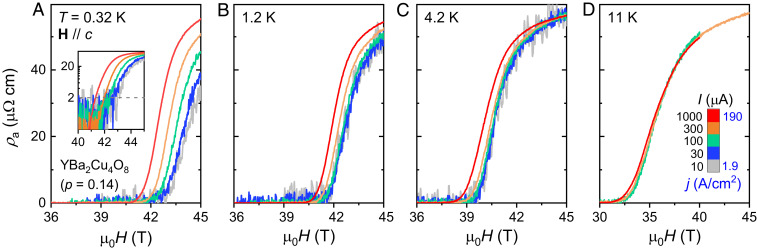

Fig. 2 shows the longitudinal resistivity ρa of a Y124 crystal measured in a magnetic field up to 45 T, over the temperature range 0.32 K ⩽T⩽ 11 K and for excitation currents 10 μA ⩽I⩽ 1 mA. The resistive transition field, μ0Hr, is defined as the field strength at which the resistivity exceeds a certain value set by the noise level at the lowest excitation currents as illustrated in Fig. 2A, Inset. Below μ0Hr, vortices are assumed to be pinned and frozen into a vortex solid state, with or without long-range translational order. In a typical type-II superconductor, this field is equivalent to the irreversibility field (). At 11 K, ρa and μ0Hr are essentially independent of I as expected for a normal metallic state. At T⩽ 4.2 K, however, ρa and μ0Hr become dependent on the magnitude of I, whose effect becomes increasingly pronounced with decreasing temperature. An increase in μ0Hr of 2 T is observed at 0.32 K when I is reduced from 1 mA to 10 μA (Fig. 2A). The same behavior is observed in two other Y124 crystals measured simultaneously (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Previously, the onset of a thermal conductivity drop in Y124 below μ0H≈ 44 T at 1.6 K ⩽T⩽ 9 K has been interpreted as the manifestation of increased electron scattering due to the emergence of vortices and therefore as a signature of Hc2 (). While this field scale is comparable with the magnetic field above which ohmic behavior is restored at 4.2 K (Fig. 2C), the pronounced nonohmic behavior at T⩽ 1.2 K, extending up to 45 T, indicates that the resistive state is not a conventional metallic ground state but rather a dissipative vortex liquid (). The extent of the second vortex solid regime (i.e., the intervening regime in which μ0Hr increases with decreasing I) is smaller than that observed in Y123 at p = 0.11 (, ), possibly reflecting the improved stoichiometry in Y124 and/or the weaker strength of the charge order (, ).

Fig. 2.

Nonohmic resistivity and superconducting transitions in Y124. (A–D) Longitudinal resistivity ρa as a function of magnetic field at temperatures of (A) 0.32 K, (B) 1.2 K, (C) 4.2 K, and (D) 11 K. Excitation current I and corresponding current density j are indicated in D. ρa becomes I dependent at T⩽ 4.2 K with the onset magnetic field of finite resistivity μ0Hr shifting to higher values upon reducing I. (A, Inset) The same 0.32-K data plotted on a semilog scale. A resistivity threshold, defined by the noise level of the 10-μA sweep and marked by the horizontal dash, is used to define μ0Hr. No apparent effect of I on ρa is observed at 11 K.

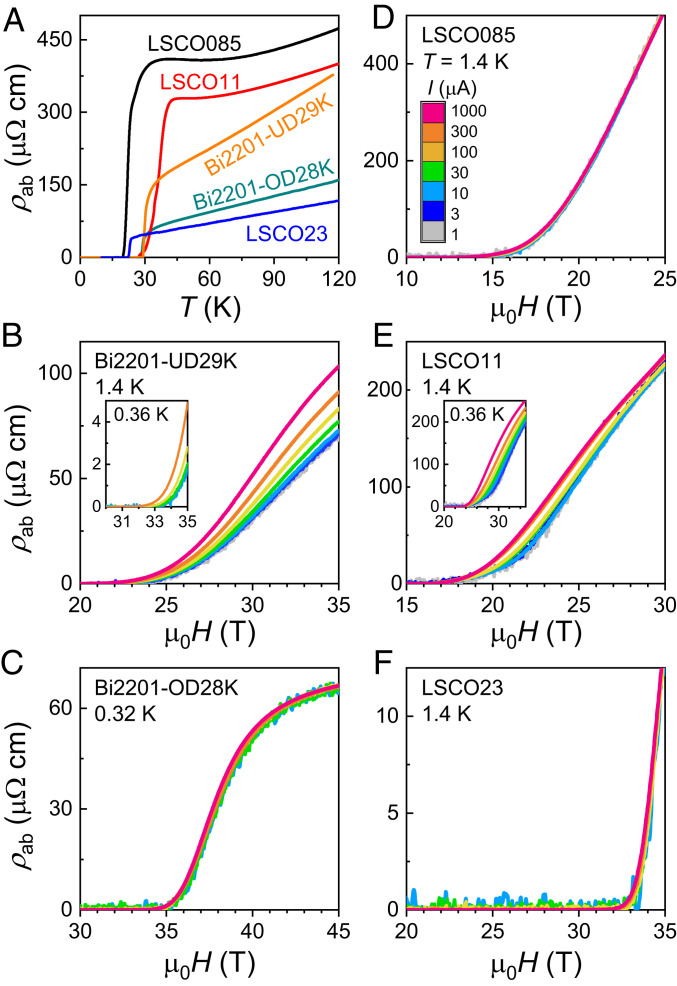

To further clarify the role of electronic disorder and charge order in the nonohmic regime, we proceed to investigate the low-T electronic transport in the more disordered cuprates LSCO and Bi2201 over a broader doping range. Fig. 3 shows the in-plane resistivity ρab of LSCO and Bi2201 crystals with doping levels extending from the highly underdoped (p = 0.085) to the heavily overdoped regime (p = 0.23). Data at the lowest temperatures at which the resistive state could be accessed with a magnetic field of 35 T (Fig. 3

B and D– F) or 45 T (Fig. 3C) are shown. In the underdoped crystals where long-range charge order is believed to be present, namely Bi2201-UD29K (underdoped, Tc = 29 K; p≈ 0.125) and LSCO11 (p = 0.11), nonohmic behavior onsets once again below 10 K and becomes more pronounced with decreasing temperature (Fig. 3

B and E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). In stark contrast, in the highly underdoped LSCO085 (Fig. 3D) and overdoped Bi2201-OD28K (overdoped, Tc = 28 K; p≈ 0.19) and LSCO23 (Fig. 3

C and F), where long-range charge order has not been observed, ρab remains ohmic down to the lowest accessible temperatures. The concurrence of nonohmic behavior and long-range charge order indicates that these two phenomena are closely linked.

Fig. 3.

Confined nonohmic behavior within the long-range charge-ordered regime. (A) In-plane resistivity ρab(T) of LSCO and Bi2201 crystals studied in this work. Doping levels p are denoted for LSCO (i.e., p = 0.085 for LSCO085) and Tc values are denoted for underdoped (UD) (p≈0.125) and overdoped (OD) (p≈0.19) Bi2201. (B–F) Magneto-resistivity ρab(μ0H) measured using excitation currents I ranging from 1 μA to 1 mA (color coded in D), at constant temperatures as indicated. No effect of the magnitude of I on ρab is observed in (D) highly underdoped LSCO085, (C) overdoped Bi2201-OD28K, and (F) LSCO23, all of which are located outside the long-range charge-ordered regime; meanwhile ρab is highly nonohmic in the resistive state of long-range charge-ordered (B) Bi2201-UD29K and (E) LSCO11.

The possibility of an extrinsic origin for the observed nonohmic behavior, such as chemical inhomogeneity and temperature instability, is carefully examined and effectively ruled out. First, the fact that ρa is I independent at T⩾ 10 K argues against a possible contribution from filamentary or surface superconductivity to the nonohmic behavior, for which an I-dependent ρa would be expected at all temperatures. Second, no discernible trace of temperature instability from the thermometer or from the samples is found in our measurements (except potentially at the highest excitation currents—see Materials and Methods for details). Finally, the observance of Ohm’s law in LSCO and Bi2201 crystals, outside of the charge-ordered doping regime, appears to rule out a disorder- or heating-induced origin of the low-T nonohmic behavior. We therefore conclude that the observed nonohmic behavior is an intrinsic property of long-range charge-ordered cuprates at low temperature and high magnetic field.

Anomalous Vortex Liquid and H–T Phase Diagram

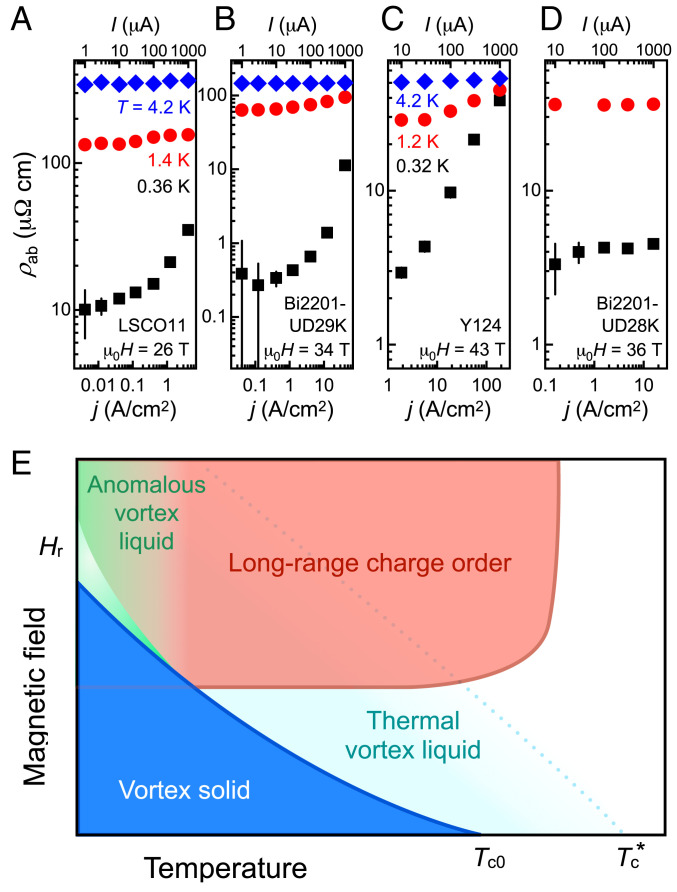

Having established the nonohmic resistivity as an intrinsic characteristic of the low-T electrical transport in long-range charge-ordered cuprates, we now proceed to explore its underlying mechanism. In a type-II superconductor, vortices can be depinned by thermal fluctuations at T≫0 or by quantum fluctuations as T→0. At T≫Tm, the temperature above which vortices become mobile, the thermal energy kBT is much larger than the pinning potential U0 and no pinning is expected. In this regime, the resistivity due to vortex flow is ohmic and given by ρflow=ρn(H/Hc2), where ρn is the normal-state resistivity (). At T→Tm, U0 becomes comparable to kBT, at which point vortex motion becomes activated, which can lead to an anomalous vortex liquid state with its resistivity following a thermally activated form: ρ=(ρflow/A) exp(−U0/T) with A≫ 1. While the identification of ρn in cuprates in the absence of superconductivity remains controversial (40–), a nonohmic resistivity can be regarded as the defining experimental signature of a vortex-liquid state. Fig. 4

A–C shows the in-plane resistivity as a function of applied current density j of long-range charge-ordered cuprates at T⩽ 4.2 K and magnetic fields near the vortex solid boundary at T→0, where thermal fluctuations are minimized. At T≈ 0.3 K, ρ in all three crystals is weakly j dependent at low j⩽ 1 A/cm2 and strongly j dependent at the intermediate regime 1 A/cm2⩽j⩽ 100 A/cm2, which appears to converge with ρ at higher temperatures. Access to the regime of j⩾ 100 A/cm2 is precluded by joule heating, despite a low contact resistance ≈1 Ω at room temperature in our pristine crystals. The dependence of ρ on j in the long-range charge-ordered crystals is characteristic of an anomalous vortex liquid occurring at T≳Tm (). Furthermore, the highly nonohmic resistivity shown in Fig. 4

A–C follows ρ∝ exp(−U0/T) with U0≈ 1 K (SI Appendix, Fig. S4) and strongly contrasts the nearly j-independent, ohmic resistivity observed in overdoped Bi2201-OD28K (Fig. 4D), despite the fact that the resistive state at μ0H= 36 T is evidently within the vortex-liquid regime (Fig. 3C). Therefore, we attribute the low-T nonohmic behavior to the emergence of an anomalous vortex liquid under high magnetic fields in the charged-ordered cuprates.

Fig. 4.

Signature of anomalous vortex liquid and schematic magnetic field−temperature phase diagram. (A–D) In-plane resistivity as a function of applied current density j on a log-log scale for (A) LSCO11, (B) Bi2201-UD29K, (C) Y124, and (D) BI2201-OD28K at temperatures as indicated (same color code for A,B and C,D, respectively). The magnetic fields at which resistivity is extracted, as indicated in each panel, are chosen to be slightly above μ0Hr at T≈ 0.3 K, where thermal fluctuations are minimized. For all three underdoped cuprates (A–C), ρ is increasingly j dependent upon decreasing temperatures, the experimental signature of an anomalous vortex-liquid state at T≳Tm, the temperature above which vortices become mobile (). In stark contrast, ρ in overdoped Bi2201-OD28K (D, p≈0.19) is independent of j within the experimental uncertainty. (E) Schematic magnetic-field−temperature phase diagram of charge-ordered cuprates. Tc0 and Tc* denote the onset temperature of zero-resistivity and fluctuating superconductivity. The dotted line encompasses a broad regime of superconducting fluctuations with mobile vortices depinned by thermal fluctuations at high temperatures and quantum fluctuations as T→0. In zero magnetic field and above Tc0, where no static vortices are expected, superconducting fluctuations can arise from the phase incoherence or spontaneous creation of vortex–antivortex pairs due to thermal fluctuations (). The vortex solid boundary is mapped by Hr(T), below which the measured resistivity descends into the noise floor (Fig. 2A). Below 10 K, the temperature at which long-range charge order and vortex solid coexist in high fields, Hr is determined by the magnitude of the driving current and a regime of fragile superconductivity with an unusually low jc (marked in light green) is realized. The neighboring regime of anomalous vortex liquid, experimentally identified by the emergence of nonohmic resistivity, does not represent a distinct state of matter but rather a crossover from the thermal vortex liquid with unpinned vortices to a low-T regime in which the vortices become increasingly pinned. This crossover is found to onset in the range 4.2 K <T< 10 K, as illustrated by the gradated color shading.

Our key findings are summarized in the H−T phase diagram shown in Fig. 4E, which illustrates the same qualitative behavior observed in the three long-range charge-ordered cuprates investigated here. The presence of long-range charge order (26272829–) within the vortex solid regime at T⩽ 10 K appears to suppress the critical current, leading to a dynamic vortex-solid boundary with respect to the driving current, in accordance with previous magnetic torque and transport experiments (, , ). While the upper field limit to which the nonohmic behavior persists is unclear from the present study, our results reveal the existence of an anomalous vortex liquid above μ0Hr at the lowest accessible temperatures, where thermal fluctuations are expected to be negligible and vortices are likely to be depinned by quantum fluctuations intensified by high magnetic fields. Importantly, the present study reveals a doping dependence that ties the emergence of the anomalous vortex liquid, irrespective of the level of disorder or structural details, to the regime of long-range charge order. We note that a very recent nonlinear magnetotransport study () on stripe-ordered Nd- and Eu-doped LSCO (p≈ 0.11) finds similar evidence for such a vortex liquid state, with an onset temperature of ≈ 10 K, which exists between μ0Hr and μ0Hc2 over a broad field range ≈ 20 T at T≈ 20 mK. The common behavior now observed in five different cuprate families (including the previously studied Y123 and Nd/Eu-LSCO) suggests a general applicability of Fig. 4E to charge-ordered cuprates, despite the fact that field-induced long-range charge order has been only indirectly inferred for Y124 and LSCO.

Intertwined Charge Order and Superconductivity

Ordinarily, the introduction of an additional periodically modulated energy landscape would act to increase U0 and strengthen vortex pinning. However, considering the extremely small amplitude of the lattice displacements brought about by the charge order (on the order of 5×10−3 Å or 0.1% of the interatomic distances) (), any strengthening of vortex pinning is likely to be negligible. Rather, the presence of long-range charge order is likely to have a detrimental effect on the superconductivity. In the following, therefore, we consider possible origins for the suppression of jc within the regime of coexisting vortex solid and charge order. In conventional superconductors, the vortex pinning strength scales with Δ2, the square of the pairing amplitude. Hence, any suppression of Δ within the charge-ordered regime would have a correspondingly adverse effect on the strength of the depinning field.

In ref. , the suppression in jc in Y123 (p = 0.11) was attributed to a transition of the pairing pattern of the superconducting condensate to accommodate the competing charge order when it becomes long ranged. A possible association to the pair-density-wave (46–) or related Fulde–Ferrel–Larkin–Ovchinnikov state () was suggested. The extent to which these exotic pairing states can lead to a dramatic suppression of jc, however, remains to be clarified. It is nevertheless worthwhile to consider the relevant length scales of the charge order and the vortex lattice and how they might affect jc. Assuming a two-dimensional array of vortices without disorder, the average distance between vortices is given by rB=Φ0/πμ0H = 70 Å, where Φ0 is the flux quantum, at the onset magnetic field (, , ) for long-range charge order of 15 T. For Y123, the charge order correlation length () ξCO increases almost fourfold from ≈70 to 300 Å in an applied magnetic field of 25 T. Although the corresponding correlation lengths for the underdoped cuprates investigated here have not been reported, a similar enhancement, e.g., from ≈20 to 80 Å, when the charge order evolves from being short ranged (, ) to long ranged, can be expected. Recent scanning–tunneling () and NMR studies () on underdoped cuprates have found compelling evidence that the emergence of charge order is associated with the vortex cores. Consequently, once ξCO exceeds rB, the long-range correlations between the pinned charge order can have an impact on the dynamical response of the vortex liquid with respect to the external driving current. Within the framework of weak collective pinning theory proposed by Larkin and coworkers () and Larkin and Ovchinnikov () (applicable to the cuprates as the depairing current density jo is much greater than the critical current density, i.e., jc/jo≪1),

where

B is the magnetic flux density and

Fp is the total pinning force experienced by a vortex bundle that is collectively pinned within a correlation volume

Vc. Therefore, an increase in

ξCO implies an enhancement in

Vc, leading to a suppression in

jc. We note that in Y123, the cuprate with the longest-range charge order, for which a large

Vc in the high-field state is expected, the suppression in

jc is found to be the most pronounced ().

Very recently, X-ray scattering experiments () on Y123 (p=0.12) in fields up to 16.5 T have found evidence that the two forms of charge order coexist in a spatially separated manner and compete with superconductivity in different ways. The charge order with three-dimensional long-range in-phase c-axis correlations is found to suppress superconductivity more strongly than its counterpart with short-range antiphase correlations. The locally distinct competition between superconductivity and charge order could lead to a spatially dependent pinning potential for the vortices and therefore a suppression in jc. Further X-ray studies on LSCO and Bi2201 are required to determine whether the same mechanism is also at play in the underdoped regime of these materials. In Y124, the absence of X-ray or NMR evidence suggests that the charge order would occur only at higher fields, possibly around 35 T above which a negative Hall coefficient () and a nonohmic resistivity are observed (Fig. 2), making transport probes more suited to study the impact of charge order in this compound.

Our current work demonstrates that the intertwining of superconductivity and charge order can lead to the emergence of an unconventional vortex phase at T≪Tc and suggests a state of locally fragile superconductivity () and anomalous metallicity in the underdoped cuprates (, ). Previously, the observation of quantum oscillations in underdoped cuprates, typically appearing soon after the resistive transition (14–), had been interpreted in terms of a reconstructed Fermi surface of the underlying normal state in which superconductivity is completely suppressed. Such an interpretation may now need to be reexamined. In particular, quantum oscillations in Y124 that onset at ≈45 T are seen to occur within the newly revealed anomalous vortex-liquid state. Proposals of quantum oscillations arising from a vortex state should thus be reconsidered (54–), while the interpretation of other high-field experiments, including thermal conductivity (), X-ray scattering (), specific heat (57–), and NMR (), may be improved by considering the possible influence of the vortex contribution.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation.

Y124 single crystals were grown using a self-flux method () in Y2O3 crucibles under an oxygen partial pressure of 400 bar, with typical dimensions of (400×100×20) μm3. The direction of current flow was determined by comparison of the resistivity curves above Tc with published data on the same batches of crystals (, ). LSCO and Bi2201 single crystals were grown using a floating-zone method and cut into rectangular platelets with typical dimensions of (1,000×400×100) μm3 and (800×150×10) μm3, respectively. Six gold wires were attached to crystals with a Hall bar geometry, using a thermally cured silver epoxy to obtain contact resistance ≈1Ω. Hole dopings p of LSCO and Bi2201 were estimated from the zero-resistivity critical temperature Tc using the empirical relationship (): Tc/Tcmax = 1 – 82.6 (p−0.16)2.

Resistivity Measurements.

Electrical resistivity was measured using a four-point method with an alternating current I at a frequency between 13 and 30 Hz. Measurements up to 35 T were carried out at the High Field Magnet Laboratory (HFML) in Nijmegen, The Netherlands and up to 45 T at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory (NHMFL) in Tallahassee, FL. Magnetic fields were applied parallel to the crystalline c axis. The smaller dimensions of the Y124 crystals and a higher background noise at 45 T limited the lowest I necessary to achieve a satisfactory signal-to-noise ratio to 10 μA in Y124, compared to 1 μA for LSCO and Bi2201 crystals up to 35 T.

Temperature Stability.

Since the dissipative power of joule heating scales as I2, any observed effect due to a variation in I may be influenced by a change in temperature. We have carefully examined the possibility of self-heating in our measurements by looking at numerous criteria and report only results in which no discernible trace of self-heating is present. At each set temperature the thermometer reading was monitored before sweeping in field, and the excitation current limited to below which an increase in the recorded temperature was observed. The voltage signals with increasing and decreasing field were also compared to examine a change in sample temperature that was not reflected in the recorded temperature. No discernible difference was found either in the thermometer readings at all I used or in the sample signals obtained on increasing and decreasing field at the highest I, indicating that the thermometer and samples were in good thermal equilibrium and remained at a constant temperature. We compared the resistivity traces measured in Y124 at T = 0.32 K using I = 1 mA and at T = 1.2 K using I = 0.3 mA (SI Appendix, Fig. S3), which have identical resistivity values at μ0H = 43 T. If the effect of varying I were solely to change the heating power, one would expect an overall overlap between the field sweeps measured at different I since they would be essentially at the same sample temperature. On the contrary, we found that these two traces coincide only at 43 T, indicating that the electrical response of the crystal has an overall change with respect to I and with respect to temperature.

In addition, we performed a control experiment to estimate the cooling power of our 3He refrigerator, using a calibrated ruthenium oxide (RuO2) chip of 1 kΩ resistance (at 2 K) as the sample. A clear sign of self-heating can be found when the RuO2 resistance starts to decrease above a threshold heating power. A cooling power of 50 and 500 nW was estimated at 0.39 and 1.4 K, respectively. Using typical room-temperature contact resistances of 1 Ω in our crystals, the threshold I limit before any putative self-heating effects was then estimated to be 0.22 mA at 0.39 K and 0.7 mA at 1.4 K. From experience, the smallness of our contact resistances at room temperature dictates that the overall contact resistance will remain metallic and therefore decrease with decreasing temperature down to cryogenic temperatures. Thus, this estimate for the threshold I limit should be viewed as a lower limit.

The dissipation power due to eddy currents has also been estimated and found to be negligibly small, as outlined below. The dissipation power is given by Pd=I2R=V2/R=(dΦB/dt)2/R=A2(dB/dt)2/R, where R and A are the resistance and surface area of the conductor, ΦB is the magnetic flux, and dB/dt is the rate at which the magnetic field changes. For charge-ordered LSCO, the surface area and resistance at 1.4 K are approximately 0.4 mm2 and 100 m, respectively, and 0.12 mm2 and 600 m for Bi2201. With a magnetic-field sweep rate of 2 T/min, we obtain Pd=1.6×10−3 pW and 2.5 ×10−5 pW for LSCO and Bi2201, respectively, at least seven orders of magnitude smaller than the cooling power in our 3He refrigerator (50 to 500 nW).

The most direct demonstration of good temperature stability in the reported results, however, is the absence of any observable current dependence in the most underdoped and overdoped crystals, as shown in Fig. 3. The irreversibility field in cuprates is known to increase sharply upon approaching T = 0. A pronounced change in the field onset of resistivity is thus expected if the sample temperature is raised by increasing I. The absence of such behavior in crystals (with similar contact resistances) outside of the long-range charge-order regime indicates that the samples measured simultaneously under identical conditions maintained good temperature stability during the measurements described here.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the HFML-Radboud University (RU)/Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO), a member of the European Magnetic Field Laboratory. This work is part of the research program “Strange Metals” (Grant 16METL01) of the former Foundation for Fundamental Research on Matter, which is financially supported by the NWO and the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant Agreement No. 835279-Catch-22). A portion of this work was performed at the NHMFL, which is supported by NSF Cooperative Agreement DMR-1644779, the state of Florida, and the US Department of Energy. A portion of this work was also supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI, Grants JP18H01165, JP19F19030, and JP19H00651) and the UK Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC, Grant EP/R011141/1). We gratefully acknowledge Suchitra E. Sebastian and Neil Harrison for initiating their study on YBa2Cu3O6+x, which led in due course to the more extensive study reported here. We also acknowledge the experimental support from Lijnis Nelemans at HFML and William Coniglio at NHMFL.

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in this article and/or SI Appendix.

References

B.

Keimer, S. A.

Kivelson, M. R.

Norman, S.

Uchida, J.

Zaanen,

From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper-oxides.

Nature

518,

179–

186 (

2015).

N. E.

Hussey, J.

Buhot, S.

Licciardello,

A tale of two metals: Contrasting criticalities in the pnictides and hole-doped cuprates.

Rep. Prog. Phys.

81,

052501 (

2018).

J.

Chang,

Direct observation of competition between superconductivity and charge density wave order in YBa2Cu3O6.67.

Nat. Phys.

8,

871–

876 (

2012).

G.

Ghiringhelli,

Long-range incommensurate charge fluctuations in (Y, Nd)Ba2Cu3O6+x.

Science

337,

821–

825 (

2012).

R.

Comin,

Charge order driven by Fermi-arc instability in Bi2Sr2−xLaxCuO6+δ.

Science

343,

390–

392 (

2014).

T. P.

Croft, C.

Lester, M. S.

Senn, A.

Bombardi, S. M.

Hayden,

Charge density wave fluctuations in La2−xSrxCuO4 and their competition with superconductivity.

Phys. Rev. B

89,

224513 (

2014).

W.

Tabis,

Charge order and its connection with Fermi liquid charge transport in a pristine high-Tc cuprate.

Nat. Commun.

5,

5875 (

2014).

R.

Comin, A.

Damascelli,

Resonant X-ray scattering studies of charge order in cuprates.

Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys.

7,

369–

405 (

2016).

N.

Doiron-Leyraud,

Quantum oscillations and the Fermi surface in an underdoped high-Tc superconductor.

Nature

447,

565–

568 (

2007).

E. A.

Yelland,

Quantum oscillations in the underdoped cuprate YBa2Cu4O8.

Phys. Rev. Lett.

100,

047003 (

2008).

A. F.

Bangura,

Small Fermi pockets in underdoped high temperature superconductors: Observation of Shubnikov - de Haas oscillations in YBa2Cu4O8.

Phys. Rev. Lett.

100,

047004 (

2008).

N.

Barisic,

Universal quantum oscillations in the underdoped cuprate superconductors.

Nat. Phys.

9,

761–

764 (

2013).

S. E.

Sebastian, C.

Proust,

Quantum oscillations in hole-doped cuprates.

Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys.

6,

411–

430 (

2015).

B.

Tan,

Fragile charge order in the nonsuperconducting ground state of the underdoped high-temperature superconductors.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.

112,

9568–

9572 (

2015).

M. K.

Chan,

Single reconstructed Fermi surface pocket in an underdoped single-layer cuprate superconductor.

Nat. Commun.

7,

12244 (

2016).

G.

Grissonnanche,

Direct measurement of the upper critical field in cuprate superconductors.

Nat. Commun.

5,

3280 (

2014).

Y.

Wang, L.

Li, N. P.

Ong,

Nernst effect in high-Tc superconductors.

Phys. Rev. B

73,

024510 (

2006).

Y.

Wang,

Dependence of upper critical field and pairing strength on doping in cuprates.

Science

299,

86–

89 (

2003).

S. E.

Sebastian,

A multi-component Fermi surface in the vortex state of an underdoped high-Tc superconductor.

Nature

454,

200–

203 (

2008).

F.

Yu,

Magnetic phase diagram of underdoped YBa2Cu3Oy inferred from torque magnetization and thermal conductivity.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.

113,

12667–

12672 (

2016).

Y.-T.

Hsu,

Unconventional quantum vortex matter state hosts quantum oscillations in the underdoped high-temperature cuprate superconductors.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.,

10.1073/pnas.2021216118 (

2021).

J. W.

Loram, J. L.

Tallon, W. Y.

Liang,

Absence of gross static inhomogeneity in cuprate superconductors.

Phys. Rev. B

69,

060502(R) (

2004).

Y.

Yu, S. A.

Kivelson,

Fragile superconductivity in the presence of weakly disordered charge density waves.

Phys. Rev. B

99,

144513 (

2019).

D. F.

Agterberg,

The physics of pair-density waves: Cuprate superconductors and beyond.

Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys.

11,

231–

270 (

2020).

S.

Gerber,

Three-dimensional charge density order in YBa2Cu3O6.67 at high magnetic fields.

Science

350,

949–

952 (

2015).

J.

Chang,

Magnetic field controlled charge density wave coupling in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6+x.

Nat. Commun.

7,

11494 (

2016).

D.

LeBoeuf,

Thermodynamic phase diagram of static charge order in underdoped YBa2Cu3Oy.

Nat. Phys.

9,

79–

83 (

2013).

T.

Wu,

Magnetic-field-induced charge-stripe order in the high-temperature superconductor YBa2Cu3Oy.

Nature

477,

191–

194 (

2011).

T.

Wu,

Emergence of charge order from the vortex state of a high-temperature superconductor.

Nat. Commun.

4,

2113 (

2013).

S.

Kawasaki,

Charge-density-wave order takes over antiferromagnetism in Bi2Sr2−xLaxCuO6.

Nat. Commun.

8,

1267 (

2017).

S.

Badoux,

Critical doping for the onset of Fermi-surface reconstruction by charge-density-wave order in cuprate superconductor La2−xSrxCuO4.

Phys. Rev. X

6,

021004 (

2016).

Y. Y.

Peng,

Re-entrant charge order in overdoped (Bi,Pb)2.12Sr1.88CuO6+δ outside the pseudogap regime.

Nat. Mater.

17,

697–

702 (

2018).

H.

Miao,

Discovery of charge density waves in cuprate superconductors up to the critical doping and beyond.

arXiv:2001.10294 (

28 January 2020).

B.

Lake,

Antiferromagnetic order induced by an applied magnetic field in a high-temperature superconductor.

Nature

415,

299–

302 (

2002).

N. B.

Christensen,

Bulk charge stripe order competing with superconductivity in La2−xSrxCuO4 (x = 0.12).

arXiv:1404.3192 (

11 April 2014).

P. M. C.

Rourke,

Fermi-surface reconstruction and two-carrier model for the Hall effect in YBa2Cu4O8.

Phys. Rev. B

82,

020514(R) (

2010).

G.

Blatter, M. V.

Feigel’man, V. B.

Geshkenbein, A. I.

Larkin, V. M.

Vinokur,

Vortices in high-temperature superconductors.

Rev. Mod. Phys.

66,

1125–

1388 (

1994).

J.

Bardeen, M. J.

Stephen,

Theory of the motions of vortices in superconductors.

Phys. Rev.

140,

A1997 (

1965).

R. A.

Cooper,

Anomalous criticality in the electrical resistivity of La2−xSrxCuO4.

Science

323,

603–

607 (

2009).

P.

Giraldo-Gallo,

Scale-invariant magnetoresistance in a cuprate superconductor.

Science

361,

479–

481 (

2018).

A.

Legros,

Universal T-linear resistivity and Planckian dissipation in overdoped cuprates.

Nat. Phys.

15,

142–

147,

2019.

K.

Behnia, H.

Aubin,

Nernst effect in metals and superconductors: A review of concepts and experiments.

Rep. Prog. Phys.

79,

046502 (

2016).

Z.

Shi, P. G.

Baity, T.

Sasagawa, D.

Popovic,

Vortex phase diagram and the normal state of cuprates with charge and spin orders.

Sci. Adv.

6,

eaay8946 (

2020).

E. M.

Forgan,

Microscopic structure of charge density waves in underdoped YBa2Cu3O6.54 revealed by X-ray diffraction.

Nat. Commun.

6,

10064 (

2015).

E.

Fradkin, S. A.

Kivelson, J. M.

Tranquada,

Colloquium: Theory of intertwined orders in high temperature superconductors.

Rev. Mod. Phys.

87,

457–

482 (

2015).

Z.

Dai, Y.-H.

Zhang, T.

Senthil, P. A.

Lee,

Pair-density waves, charge-density waves, and vortices in high-Tc cuprates.

Phys. Rev. B

97,

174511 (

2018).

Y.

Wang,

Pair density waves in superconducting vortex halos.

Phys. Rev. B

97,

174510 (

2018).

P.

Fulde, R. A.

Ferrell,

Superconductivity in a strong spin-exchange field.

Phys. Rev.

135,

A550 (

1964).

S. D.

Edkins,

Magnetic field-induced pair density wave state in the cuprate vortex halo.

Science

364,

976–

980 (

2019).

A. I.

Larkin, Y. N.

Ovchinnikov,

Pinning in type II superconductors.

J. Low Temp. Phys.

34,

409–

428 (

1979).

J.

Choi,

Spatially inhomogeneous competition between superconductivity and the charge density wave in YBa2Cu3O6.67.

Nat. Commun.

11,

990 (

2020).

A.

Kapitulnik, S. A.

Kivelson, B.

Spivak,

Colloquium: Anomalous metals: Failed superconductors.

Rev. Mod. Phys.

91,

011002 (

2019).

A.

Melikyan, O.

Vafek,

Quantum oscillations in the mixed state of d-wave superconductors.

Phys. Rev. B

78,

020502(R) (

2008).

S.

Banerjee, S.

Zhang, M.

Randeria,

Theory of quantum oscillations in the vortex-liquid state of high-Tc superconductors.

Nat. Commun.

4,

1700 (

2013).

M. R.

Norman, J. C. S.

Davis,

Quantum oscillations in a biaxial pair density wave state.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.

115,

5389–

5391 (

2018).

S. C.

Riggs,

Heat capacity through the magnetic-field-induced resistive transition in an underdoped high-temperature superconductor.

Nat. Phys.

7,

332–

335 (

2011).

C.

Marcenat,

Calorimetric determination of the magnetic phase diagram of underdoped ortho II YBa2Cu3O6.54.

Nat. Commun.

6,

7927 (

2015).

B.

Michon,

Thermodynamic signatures of quantum criticality in cuprate superconductors.

Nature

567,

218–

222 (

2019).

R.

Zhou,

Spin susceptibility of charge-ordered YBa2Cu3Oy across the upper critical field.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.

114,

13148–

13153 (

2017).

S.

Adachi,

Preparation of YBa2Cu4O8 single crystals in Y2O3 crucible using O2-HIP apparatus.

Physica C

301,

123–

128 (

1998).

N. E.

Hussey, K.

Nozawa, H.

Takagi, S.

Adachi, K.

Tanabe,

Anisotropic resistivity of YBa2Cu4O8: Incoherent-to-metallic crossover in the out-of-plane transport.

Phys. Rev. B

56,

R11423(R) (

1997).

C.

Proust, B.

Vignolle, J.

Levallois, S.

Adachi, N. E.

Hussey,

Fermi liquid behavior of the in-plane resistivity in the pseudogap state of YBa2Cu4O8.

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A.

113,

13654–

13658 (

2016).

M. R.

Presland, J. L.

Tallon, R. G.

Buckley, R. S.

Liu, N. E.

Flower,

General trends in oxygen stoichiometry effects on Tc in Bi and Tl superconductors.

Physica C

176,

95–

105 (

1991).

Anomalous vortex liquid in charge-ordered cuprate superconductors

Anomalous vortex liquid in charge-ordered cuprate superconductors