Edited by Gene E. Robinson, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Urbana, IL, and approved February 3, 2021 (received for review June 11, 2020)

Author contributions: O.P. designed research; D.M.T.N. and A.M. performed research; M.L.I., K.B., and G.J.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; D.M.T.N., A.M., and O.P. analyzed data; and D.M.T.N. and O.P. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

We show that bees locate their queen by performing a cascade of “scenting” events, where individual bees direct their pheromone signals by fanning their wings. The bees create a dynamic spatiotemporal network that recruits new broadcasting bees over time, as the pheromones travel a distance that is orders of magnitude the length of an individual. We develop high-throughput machine learning tools to identify the locations and timings of scenting events, and demonstrate that these events integrate into a global “map” that leads to the queen. We use these results to build an agent-based model that illustrates the advantage of the directional signaling in amplifying the pheromones, thus leading to an effective search and aggregation process.

Honeybee swarms are a landmark example of collective behavior. To become a coherent swarm, bees locate their queen by tracking her pheromones. But how can distant individuals exploit these chemical signals, which decay rapidly in space and time? Here, we combine a behavioral assay with the machine vision detection of organism location and scenting (pheromone propagation via wing fanning) behavior to track the search and aggregation dynamics of the honeybee Apis mellifera L. We find that bees collectively create a scenting-mediated communication network by arranging in a specific spatial distribution where there is a characteristic distance between individuals and directional signaling away from the queen. To better understand such a flow-mediated directional communication strategy, we developed an agent-based model where bee agents obeying simple, local behavioral rules exist in a flow environment in which the chemical signals diffuse and decay. Our model serves as a guide to exploring how physical parameters affect the collective scenting behavior and shows that increased directional bias in scenting leads to a more efficient aggregation process that avoids local equilibrium configurations of isotropic (nondirectional and axisymmetric) communication, such as small bee clusters that persist throughout the simulation. Our results highlight an example of extended classical stigmergy: Rather than depositing static information in the environment, individual bees locally sense and globally manipulate the physical fields of chemical concentration and airflow.

Animals routinely navigate unpredictable and unknown environments in order to survive and reproduce. One of the prevalent communication strategies in nature is conducted via volatile signal communication, for example, pheromones (1, 2). As the range and noise tolerance of information exchange is limited by the spatiotemporal decay of these signals (3, 4), animals find creative solutions to overcome this problem by leveraging the diffusivity, decay, and interference with information from other individuals (567–8).

For olfactory communication, honeybees use their antennae to recognize and respond to specific odors. Recent studies have revealed the bees’ distinct electrophysiological responses to different chemicals with quantifiable preferences (9). Olfactory communication with pheromones is crucial for many coordinated processes inside a honeybee colony, such as caste recognition, regulating foraging activities, and alarm broadcasting (1011–12). Studies have shown that the queen mandibular pheromone regulates gene expression in the brains of workers, inducing changes in downstream behaviors, such as nursing and foraging (13). Among worker bees, adult foragers produce ethyl oleate, a chemical inhibitory factor that plays a role in delaying foraging in younger workers (14). In this work, we study how bees use pheromones in the context of swarm formation. To become a coherent swarm, honeybees must locate their queen by tracking her pheromones that decay rapidly in time and space. How can honeybees that are far away from the queen locate her? The specific mechanisms of the collective signal propagation strategy are still unknown.

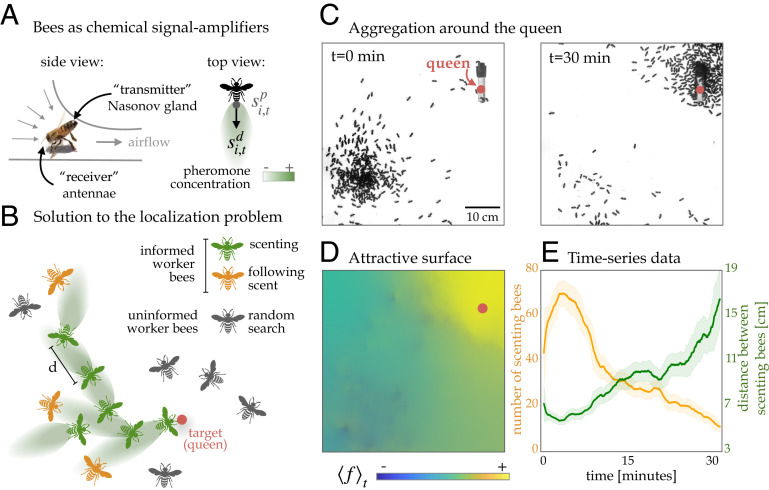

The mechanism to locating the queen involves a behavior called “scenting,” where bees raise their abdomens to expose the Nasonov pheromone gland and release the chemicals (1516–17) (Fig. 1A and Movie S1, Left). This common behavior is also seen in other scenarios, such as scenting at the hive’s entrance to orient foragers coming back to the hive and on food locations (e.g., flowers) (18, 19). So far, scenting has only been characterized at the level of an individual bee. We investigate how this behavior manifests at the level of a group of bees performing the task of localizing the queen for swarming.

Honeybees use directed volatile communication to solve a localization problem of finding their queen. (A) Pheromone sensing bees amplify the signal by opening the Nasonov gland in their abdomen and fan their wings to transmit their pheromones backward (a behavior called “scenting”). In the top view of the scenting bee, is the position of a given bee, and

In the traditional chemical signaling chemotaxis and quorum sensing scheme, the produced chemical signal by an individual is isotropic, or nondirectional and axisymmetric, as seen in early embryonic development (20, 21) and aggregation of amebae in Dictyostelium (2223–24). Conversely, scenting bees create a directional bias by fanning their wings, which draws air along the pheromone gland along their anteroposterior axis (Fig. 1A). Thus, in addition to diffusion or the transport of the chemicals through random motion, the pheromone signals are also subject to the process of advection, that is, the transport of the chemicals by air motion created by the wing fanning. We show that, when bees perform the scenting behavior, they fan their wings to direct the signal away from the queen and toward informed bees following the scent and the rest of the uninformed swarm (Fig. 1B). This directional bias increases the probability that distant bees may sense those amplified pheromones, upon which they also stop at a certain distance from the scenting bee and amplify the signal along their own anteroposterior axis. The combination of detection and “rebroadcast” leads to a dynamic network that recruits new broadcasting bees over time, as the pheromones now travel a distance that is orders of magnitude the length of an individual. What are the dynamics in the number of scenting bees during the swarming process? Is there a characteristic distance that defines the pheromone detection range for scenting bees? What are the advantages of a directional communication strategy vs. an isotropic one? And how do the bees harness the physics of directed signals to create an efficient communication network? To address these questions, we combined a behavioral assay, machine learning solutions for organism tracking and scenting detection and computational agent-based modeling of the communication strategy in honeybees and characterize the advantage of collective directional scenting.

Materials and Methods

To quantify the correlation between the scenting behavior of the bees, localization of the queen, and the aggregation process, we established a behavioral assay in which worker bees search for a stationary caged queen in a semi–two-dimensional (2D) arena (see SI Appendix, section A for more details). We recorded the search and aggregation behavior of the bees from an aerial view for 1 h to 2 h (see Movie S1 for a closeup example scenting bee with her abdomen pointed upward and wing-fanning behavior in this experimental arena, in contrast with a nonscenting bee standing still). To extract data from the recordings, we then developed a markerless, automatic, and high-throughput analysis method using computer vision methods and convolutional neural networks (CNNs) (25). This pipeline allows us to detect individual bees as well the positions and orientations of scenting bees (see SI Appendix, section B and Fig. S2 for more details, and see Movie S2 for a movie of the example in SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and C).

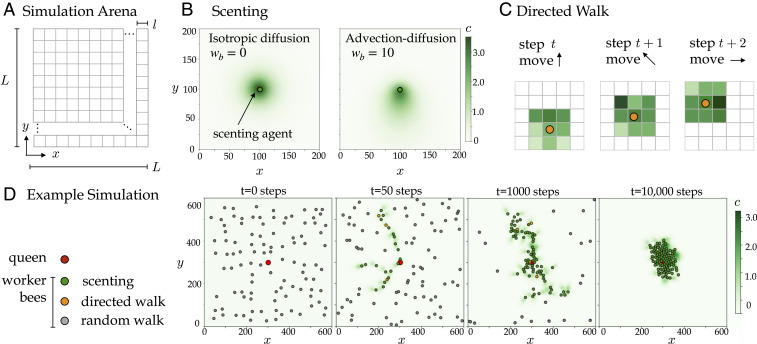

To identify the unifying behavioral principles that harness the dynamics of volatile signals, we developed a model that captures two important physical dynamics surrounding individual bees, substance advection–diffusion and sensing local concentration gradients, while they perform search and identification (26). Our agent-based model is embedded in a flow environment where individuals can sense local concentrations of pheromones and propagate them backward as well as move up the gradient (see SI Appendix, section F and Fig. 3 for full model details).

Behavioral Assay Results

Localization Is Correlated with Scenting.

In the 2D experimental arena, worker bees placed at the opposite corner from the queen explore the space and eventually aggregate around the queen’s cage after

To show that the attractive surface

A Characteristic Distance between Scenting Bees.

The aggregation process is accompanied by a sharp increase in the average number of scenting bees, followed by a slow decay, until there are few scenting bees and the majority of the bees are aggregated around the queen (Fig. 1E, orange curve). See Movie S3 for the experiment shown in Fig. 1 C–E, with the attractive surface reconstruction and time series data. We also characterize the temporal dynamics of the distance between neighboring scenting bees, which are treated as adjacent points in the Voronoi diagram for each frame (see example diagram in SI Appendix, Fig. S2 E and F and section C for more details). Throughout the growth in the number of scenting bees, the distance between scenting bees decreases to a minimal value, then increases as the number of scenters decreases (Fig. 1E, green curve).

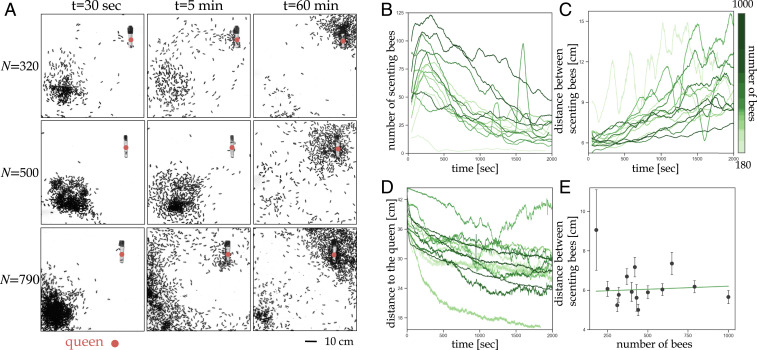

To show the reproducibility of the behavioral assay and assess the effect of group size in the aggregation process, we tested 14 group sizes ranging from approximately 180 to 1,000 bees. Three example experiments with

Distance between scenting bees is invariant to bee density. (A) Example experiments of various bee densities, each with three snapshots showing the process of aggregation around the queen’s cage over 60 min. (B) The average number of scenting bees over time for all experiments of various densities. There are more scenting bees with higher number of bees in the arena. Across densities, we observe a typical characteristic of a sharp increase in scenting bees at the beginning and decrease over time. (C) The average distance to the queen over time for all experiments of various densities. This distance gradually decreases as bees aggregate around the queen. The positive correlation between distance to queen and number of scenting bees is evidence for the functional importance of scenting events to the problem of queen finding. (D) The average distance between scenting bees over time for all experiments of various densities. Across densities, these distances are fairly constant at the beginning around the peaks in B, and increase over time. (E) The average distance between scenting bees at the peak in number of scenting bees as a function of density. Error bars represent the standard deviation over all of the distances for each density. The distance between scenting bees is approximately constant across densities, except for a low-density outlier. A linear model (green line) is fit to the data, excluding the outlier, with a slope of

The time evolution of the average distance from all bees in the arena to the queen is shown in Fig. 2C. There are no clear distinctions between the temporal dynamics of this distance as a function of density. For most densities, there is a sharp drop in this distance to the queen very early on (

We also measured the distance between neighboring scenting bees over time for all group sizes (Fig. 2D). This distance shows a characteristic gradual increase over time. At the beginning of the aggregation process at the peaks in scenting bees, this distance is fairly constant across all sizes, ranging from 5.00 cm to 7.35 cm, with an outlier from the lowest group size experiment at 9.06 cm (Fig. 2E). A linear model is fitted to the data (excluding the outlier) with the slope

These experimental results, scenting behavior with wing fanning to direct pheromones, the threshold-dependent triggering of this behavior, and a characteristic distance between scenting bees, serve as core ingredients for our agent-based model. We will use the model as a proof of concept of our proposal of the mechanistic localization behavior, described in more detail in the next section. The goal of our modeling is to test hypotheses of the mechanisms behind the phenomenon and explore the possible emergent patterns that arise to assess the effect of the directional signaling strategy employed by the bees.

Agent-Based Model Results.

Model Predicts Optimal Signal Propagation within a Range of Behavioral Parameters.

We systematically explore a range of values for the directional bias

Scenting model. (A) Our

We quantify aggregation around the queen through the average distance of worker bees to the queen,

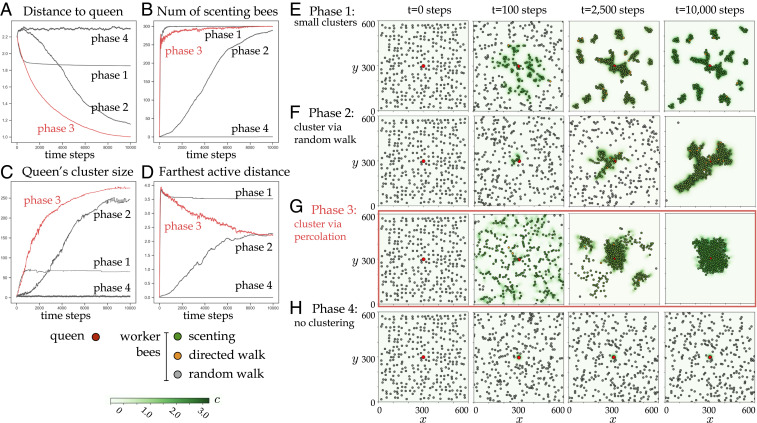

Phase 1.

For low values of both

Directional bias is associated with optimal search and aggregation in the scenting model. (A) The average distance of the worker bees to the queen as a function of time steps, for examples of the four different phases. (B) The average number of scenting bees as a function of time steps, for examples of the four different phases. (C) The average queen’s cluster size as a function of time steps, for examples of the four different phases. (D) The average distance of the farthest active bee to the queen as a function of time steps, for examples of the four different phases. (E–H) Example of a simulation from the four different phases, showing a temporal series of snapshots. The queen is shown as a red filled circle, and worker bees are shown as a red filled circle colored by their internal state: scenting (green), performing a directed walk up the pheromone gradient (orange), and performing a random walk (gray). The instantaneous pheromone concentration C(x,y,t) corresponds to the green color scale. Simulation parameters are

Phase 2.

At higher values of

Phase 3.

At low values of

Phase 4.

When the activation threshold

The existence of a phase 3 in the computational model suggests that using a directional signal is advantageous, as this phase does not exist in the absence of directional bias (

The Spatial–Temporal Shapes of Clusters in Experiments and Simulations.

To connect the results of the model and the experiments, we analyze the clusters that change in shape and size over time in the experiments (for densities ranging from

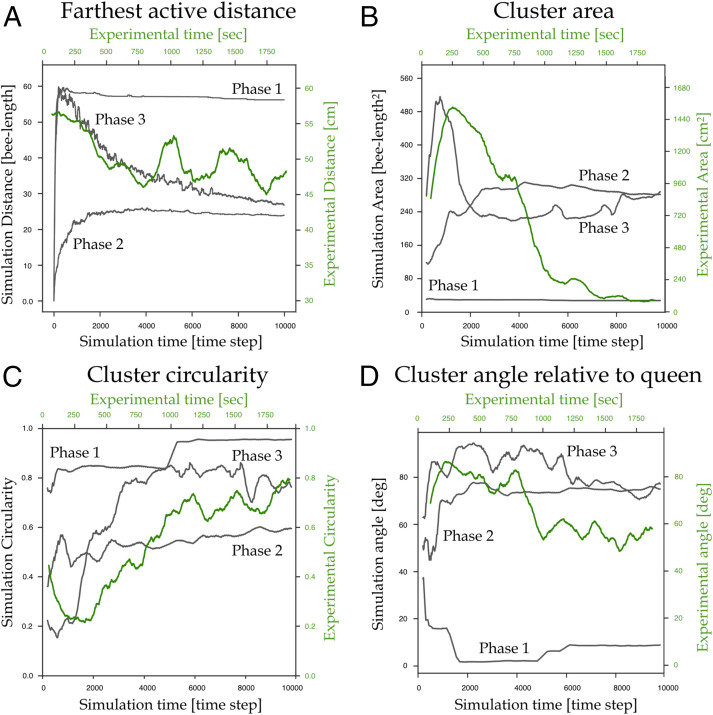

To quantitatively compare the experiments to the different phases in the model, we measure farthest active distance, cluster area, cluster circularity, and cluster angle to the queen and show the time series of these attributes in Fig. 5. We exclude phase 4 simulations from these analyses, as the virtual bees are never activated, and no clusters form. First, in Fig. 5A, we show the distance to the queen from the farthest active bee (in experiments: scenting bees; in model: scenting or bee walking up the gradient) as a measure that differentiates the phases based on how far the signals propagate. In phase 1, this distance plateaus at a relatively high value when bees remain in small clusters throughout the arena. In phase 2, this distance plateaus at a relatively low value as the bees must be closer to the queen to be activated, and signals do not propagate as far as in phase 3, where we see a high initial distance as the percolation network forms, and a gradual decrease as bees cluster around the queen. The temporal dynamics of the experimental curve (green) are similar to the phase 3 simulation. Note that the oscillations in the experimental series are likely due to the spontaneous scenting events that may come from bees far away and not yet in the queen’s cluster. For each cluster attribute, we also measure the Pearson correlation between the experiments and the simulations in each phase, presented in SI Appendix, Table S4. For the farthest active distance, the coefficients between the experiments and the simulations in phases 1, 2, and 3 are −0.075, −0.662, and 0.759, respectively. For all attributes, the number of samples used to compute the correlation is

Cluster properties of the experiments and simulations. For all panels, the green curve shows the average in experiments, and labeled gray curves show the average in different phases of the simulations. (A) The distance of the farthest active bee to the queen as a measure of how far the signals propagate. (B) The cluster area over time. (C) The cluster circularity over time. (D) The cluster angle relative to the queen over time.

Second, we quantify the cluster area for both the experiments and the simulations (Fig. 5B). In phase 1, the cluster around the queen is very small, as most bees are stuck in local equilibria. In phase 2, the cluster gradually increases and plateaus at a relatively intermediate size. In phase 3 and in the experiments, the cluster area quickly increases as the percolation network activates, and gradually decreases as bees approach and swarm around the queen. Shown in SI Appendix, Table S4, the coefficients between the experiments and the simulations in phases 1, 2, and 3 are 0.527, −0.784, and 0.762, respectively.

Third, we quantify the circularity of the clusters over time, in Fig. 5C, defined as

Finally, in Fig. 5D, we show the angular deviation of the cluster orientations from the orientation leading to the queen. This relative angle plateaus for phases 1 and 2, in which the process of clustering around the queen is less dynamic and the cluster’s final shape is determined earlier. In phase 3 and the experiments, the cluster gradually orients toward the queen over time. We compute the angular correlation between the relative angle time series using

Overall, we compare the structural phases we observe in the simulations and the spatiotemporal structures formed by the bees in the experiments. By extracting the four properties of the clustering dynamics and comparing the experimental data to the simulation data from phases 1 through 3, we show that the clustering of the bees in our experiments tend to behave inconsistently with virtual bees in phases 1 and 4. Hence, the real-world system likely exists within phase 2 and/or phase 3 of the model.

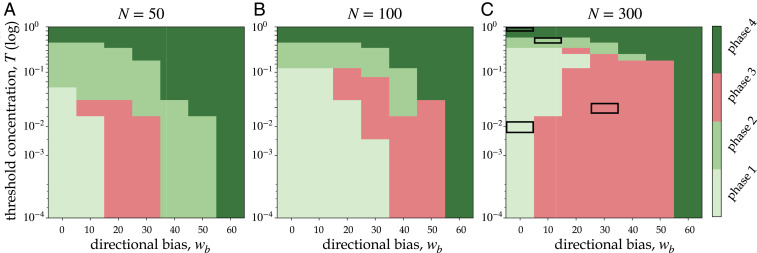

The Effect of Bee Density on the Phase Boundaries.

We use our model to construct phase diagrams for three different densities, low (

The effect of bee density on phase boundaries. Phase diagrams constructed from scenting model dynamics using summary heat maps in SI Appendix, Fig. S5 as a function of

Phase 2 is typically the result of intermediate

Discussion and Conclusion

Combining experiments and high-throughput machine vision tracking of location and scenting behavior, we investigated the communication mechanisms that honeybee swarms employ to collectively locate their queen, a difficult problem given the limited information available from short-lived pheromone signals. We find that individual bees act as receivers and senders of signals by using the Nasonov scenting behavior, releasing pheromones from the glands and fanning their wings to direct the signals backward (Fig. 1 A and B and Movie S1, Left). In an arena with a caged queen, bees were quick to activate a collective communication network, as we see a sharp, early-time increase in the number of scenting bees (Figs. 1E and 2B). In this network, scenting bees stand at a characteristic distance from their neighbors while dispersing signals (Fig. 2E), which suggests a concentration threshold in the activation mechanism of individual bees’ scenting behavior. We show that the scenting events are highly correlated with the collective aggregation around the queen (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Together, these experimental results provide testable hypotheses of the mechanisms of this collective communication strategy and of whether the threshold-dependent directional signaling behavior is advantageous—concepts that we explore with the agent-based model.

The experimental findings guide our design and implementation of an agent-based model of the queen localization phenomenon. We model individual bees as agents with simple rules for movement, detection of pheromone based on a concentration threshold, directed signaling, and chemotaxis to move up the local gradient (Fig. 3). The bee agents are not aware of the queen’s location or of the global pheromone profile in the flow environment. We show that, by only local interactions, these agents are able to aggregate around the queen mostly quickly and efficiently when they implement directed signaling within a range of bias values (i.e.,

In addition to presenting mechanistic details about the queen localization phenomenon in honeybees, we have also developed an effective image analysis pipeline for markerless, automatic, and high-throughput honeybee detection and behavior recognition (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Our approach uses state-of-the-art neural network models that are trained on our honeybee data and can be retrained and applied to other systems. Our high-throughput pipeline can be easily improved for future applications. First, the detection of individual bees currently employs a classical computer vision approach of simple Otsu’s adaptive thresholding, morphological transformations, and connected components. While these methods are quick and sufficient to identify bees from background, they struggle to separate bees when they significantly touch or overlap in the image, a problem exacerbated by our backlight system. In future designs, we will modify our experimental setup to use different lighting systems where more features on bees are visible, allowing the usage of CNNs for the task of image segmentation to detect more individual bees in dense environment (e.g., ref. 27). Additionally, while using the wing angle as a proxy for scenting in static images is effective, scenting is a time-dependent behavior which could be more accurately identified using information from multiple frames. Temporal information can be incorporated using activity recognition networks (28, 29) on labeled videos of bees. This will require tracking individual bees over time to build a labeled dataset composed of short movies of the scenting behavior. We will explore recent efforts in automatic tracking of bees, such as works by ref. 30. The ability to track the scenting behavior of bees over time will allow us to answer interesting questions regarding the roles worker bees play in this swarming context. For example, does every bee eventually scent or does only a proportion of the same bees scent while others follow the pheromone trails to the queen?

Various future directions arise. The model will allow testable predictions about the resilience of the communication network. This concept includes assessing the effect of node failure via removal of some signaling bees, interference with a secondary signal via introducing artificial pheromone to the network, and the disruption of pheromone flows in the presence of wind. Experiments can then be performed to test the model’s phenomenological predictions. Together, the tools will allow better understanding of how the dynamic nature of the network allows the swarm to overcome local obstacles such as solid objects, and deal with a nonstationary search target, as well as turbulent airflow and conflicting chemical signals.

From a physics perspective, our active system functions by coupling flows and forces in the presence of feedback (3132–33). The individual building blocks (in this case, a bee) can sense their microenvironment (flow, forces, chemical content) and respond in a way that promotes survival; typically, the response changes the macroenvironment the individual is embedded in, thus creating a perpetual coupling between the individuals, the group, and the environment. From a biological perspective, our approach is an extension of the studies of classical stigmergy (34) wherein organisms deposit and respond to static information in the environment. In contrast, the bees in our system are able to sense local chemicals but also manipulate the global physical fields by actively directing signals with the scenting behavior. Harnessing the bees’ natural solutions to communication—honed by eons of evolution, selection, and refinement—we can not only more deeply understand collective animal behavior but leverage that understanding to create bioinspired system designs in the fields of dynamic construction materials, swarm robotics, and distributed communication.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant DGE 1650115 (D.M.T.N.), and NSF Physics of Living Systems Grant 2014212 (O.P.). Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF. We also acknowledge funding from the University of Colorado Boulder, BioFrontiers Institute (internal funds), the Interdisciplinary Research Theme on Autonomous Systems (O.P.), Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University Graduate University (K.B. and G.J.S.), and Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (G.J.S.). We thank Seneca Kristjonsdottir and Christopher Borke for bee management, Gary Nave and Michael Neuder for assistance in developing image analysis pipeline, Aubrey Kroger and Emily Walker for annotating images, and Raphael Sarfati and Chantal Nguyen for reading and commenting on the manuscript. We thank Prof. L. Mahadevan, Prof. Massimo Vergassola, Prof. Gene E. Robinson, Prof. Olav Rueppell, and members of the O.P. laboratory for insightful feedback and discussions.

Data Availability

Computational code for the ML-based image analysis and for the agent-based model has been deposited in GitHub at https://github.com/peleg-lab/CollectiveScentingABM and https://github.com/peleg-lab/CollectiveScentingCV.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Flow-mediated olfactory communication in honeybee swarms

Flow-mediated olfactory communication in honeybee swarms