Edited by Yu-li Wang, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Yale E. Goldman December 7, 2020 (received for review May 23, 2020)

Author contributions: J.O.R. and M.F. designed research; C.S., B.A., and J.C.J.H. performed research; C.S. and B.A. analyzed data; and C.S., B.A., J.O.R., and M.F. wrote the paper.

1C.S. and B.A. contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

Cells exert forces on their environment by contracting actin networks, friction of intracellular F-actin flow, and polymerization when they move, e.g., during tumor metastasis or development. In this context, the relation between adhesion and cell velocity is a general cell-type-independent observation, the investigation of which bears the chance of understanding basic mechanisms. Restricting cell motion to one-dimensional lanes simplifies the problem and allows for comparison to mathematical models. Polymerization at the cell’s leading edge drives F-actin network flow and pushes the membrane. The drag of detaching the cell, the membrane, and the cell body resist motion. Since only velocity-controlled forces shape motion, cells can move even across highly adhesive areas without getting stuck.

The biphasic adhesion–velocity relation is a universal observation in mesenchymal cell motility. It has been explained by adhesion-promoted forces pushing the front and resisting motion at the rear. Yet, there is little quantitative understanding of how these forces control cell velocity. We study motion of MDA-MB-231 cells on microlanes with fields of alternating Fibronectin densities to address this topic and derive a mathematical model from the leading-edge force balance and the force-dependent polymerization rate. It reproduces quantitatively our measured adhesion–velocity relation and results with keratocytes, PtK1 cells, and CHO cells. Our results confirm that the force pushing the leading-edge membrane drives lamellipodial retrograde flow. Forces resisting motion originate along the whole cell length. All motion-related forces are controlled by adhesion and velocity, which allows motion, even with higher Fibronectin density at the rear than at the front. We find the pathway from Fibronectin density to adhesion structures to involve strong positive feedbacks. Suppressing myosin activity reduces the positive feedback. At transitions between different Fibronectin densities, steady motion is perturbed and leads to changes of cell length and front and rear velocity. Cells exhibit an intrinsic length set by adhesion strength, which, together with the length dynamics, suggests a spring-like front–rear interaction force. We provide a quantitative mechanistic picture of the adhesion–velocity relation and cell response to adhesion changes integrating force-dependent polymerization, retrograde flow, positive feedback from integrin to adhesion structures, and spring-like front–rear interaction.

Cell motility is crucial for various processes, ranging from migration of cells in development and tumor metastasis to neuronal growth-cone advance in the formation of neuronal connectivity (12–3). Many cells form a large, thin protrusion in the direction of motion when moving on flat substrates (4). The whole protrusion is mechanically stabilized by adhesion with the substrate (56789–10). Treadmilling of a dense network of branched actin filaments (F-actin) inside it pushes the leading-edge membrane forward (1112–13). That generates motion, since the filament barbed ends polymerize at the leading edge of the lamellipodium and, thus, maintain the protrusion force (141516–17). Each added monomer extends the filament by the length = 2.7 nm. Further back, the pointed ends depolymerize, and filaments are severed (12, 13).

The F-actin network moves relative to the protrusion’s leading edge due to polymerization (11, 18). The velocity of this retrograde flow is the network-extension rate

The F-actin network transmits the protrusion force via adhesion sites and adhesive forces to the substrate (2324–25). Studies on network flow (19, 21, 22) and measurements of the dynamic force–velocity relation (16) showed that the protrusion force is transmitted to adhesion structures by friction between the flowing F-actin network and these structures, and not by a direct elastic connection between leading-edge membrane and adhesion sites.

Retrograde flow is the fastest in the lamellipodium subregion of the F-actin network directly at the leading-edge membrane. It substantially slows down at the transition to the lamella region, which adjoins the lamellipodium (262728–29). Nascent focal adhesion (FA) sites start to emerge under the lamellipodium and mature toward the lamella (20, 25, 27, 30). The boundary between the lamella and the lamellipodium coincides with an elevated density of FAs (20). Retrograde flow slows down at these FAs (20), relative tension gradients are large (24), and velocity gradients get steeper with increasing adhesion density (20, 31). These observations illustrate directly the friction between the flowing network and stationary structures.

The density of adhesion-related structures and strength of adhesion can be controlled experimentally by the substrate density of the ligand (e.g., Fibronectin) of the adhesion molecule, which is integrin most of the time (678–9, 313233–34). The percentage of cell ventral area covered by adhesion structures increases with Fibronectin density in PtK1 cells (31). Varying Fibronectin density led to the discovery of the biphasic dependency of the cell velocity on ligand density, which is a fundamental and universal experimental observation in this context (678–9, 3131–33, 35). The existence of a velocity maximum in dependence on adhesion has been explained by the action of adhesion on both cell front and rear (6789–10, 24, 31, 32, 36). The velocity increases initially with adhesion strength, since pushing force at the front can be transmitted better to the substrate. Moving cells need to pull the rear membrane off the adhesion bonds, which causes resistance to motion and decreases velocity with increasing adhesion.

The initial hypothesis on the mechanism of front–rear interaction was graded adhesion allowing for pulling off rear adhesions with force from the front transmitted by stress fibers, since adhesions at the front were assumed to be stronger than those at the rear (37, 38). Detailed experimental analysis revealed complex feedbacks between adhesion and intracellular force generation and could not directly confirm the graded adhesion mechanism (20, 31, 33). It remained unresolved whether adhesion at the front needs to be stronger than at the rear and where forces resisting motion actually originate. As yet, there is little mechanistic and quantitative understanding of effects of adhesion on front versus rear regions of the cell, or front–rear interaction required for the suggested mechanism of the biphasic relation to hold. To resolve this issue, we need to measure steady-state cell velocities and length at different adhesion strengths; study the dynamic adaptation at adhesion transitions, where front and rear transiently experience different ligand densities; and compare results to force models.

In the present study, we restricted cell motility to one-dimensional motion, which substantially simplifies the analysis by avoiding shape changes occurring on two-dimensional substrates (Movie S1) (33). In addition, since heterogeneities within cell populations easily obscure weak effects of adhesion, we subjected individual cells to steps of adhesion strength and measured relative velocity changes of single cells. Micropatterning techniques like microcontact printing (39) have been used to confine cell migration to protein-coated one-dimensional lanes (4041–42) or to impose defined cell shapes (434445–46). However, so far, micropatterns with variations of protein coating within the pattern (47) have not been used to study the velocity and length adaptation of cells to stepwise variations of adhesion strength.

We investigated the mechanism of the biphasic adhesion–velocity relation and the character of the front–rear interaction by studying motion of cells on Fibronectin lanes fabricated with two-step microcontact printing. We started with recapitulating the biphasic adhesion–velocity relation for MDA-MB-231 cells. The force balance at the leading edge and force dependency of polymerization allow derivation of a mathematical model and, thus, for quantitatively analyzing our results and also published data for keratocytes, PtK1 cells, and CHO cells. This quantitative analysis provides mechanistic insight into the biphasic relation. The stationary case with cell front and back moving on homogeneous Fibronectin density with the same velocity is not sufficient to investigate the coupling between front and rear. Therefore, we perturbed motion by alternating Fibronectin density steps and analyzed the dynamics of cells during transition across the density interfaces. This provides insight into the adhesion–length relation and the character of the force mediating front–rear interaction.

Results

The Velocity of MDA-MB-231 Cells on Microlanes Shows Biphasic Dependence on Fibronectin Density.

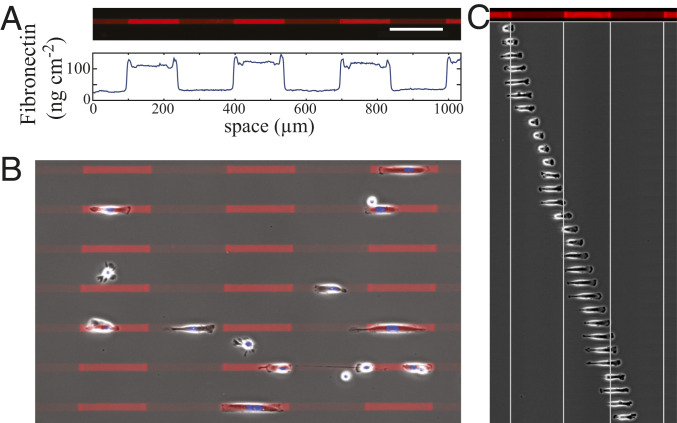

We developed a microcontact printing protocol for Fibronectin-coated microlanes with varying density that is based on two stamping steps (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). It created 15-

Fibronectin lanes and cell motion. (A) Fluorescence image of a Fibronectin-coated lane with fields of different Fibronectin density shown below. (Scale bar: 150

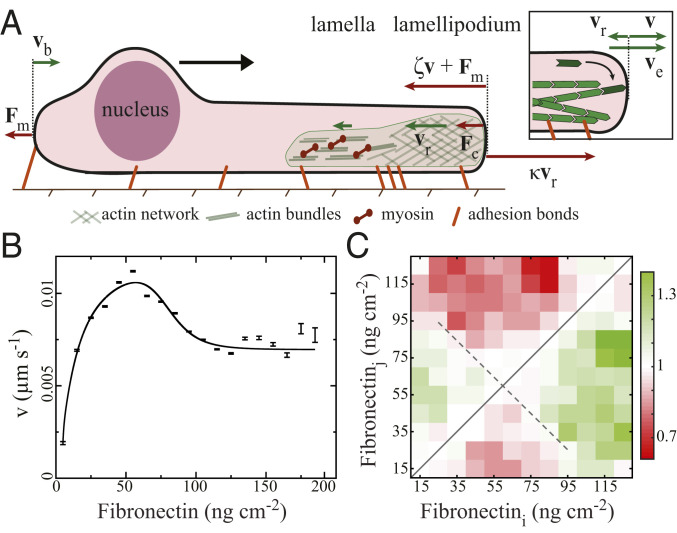

We used lanes with different combinations of Fibronectin densities and analyzed more than 15,000 single-cell tracks. The velocity averaged over the cell population shows the biphasic behavior with maximal velocity for intermediate Fibronectin densities (Fig. 2B) that was reported by several studies for different cell types (678–9, 31, 33, 35). Published data did not permit a clear distinction between a monotonous decrease of the cell velocity with increasing adhesion strength beyond the velocity maximum and saturating effects of adhesion on the velocity. We have chosen a sufficiently small step size in coating densities and a sufficiently large number of measurements per data point to clearly identify saturation.

The adhesion–velocity relation. (A) Sketch of a cell with velocities of the leading edge

We also analyzed the velocity changes at transitions between different Fibronectin densities with regard to the biphasic relation at the single-cell level (Fig. 2C and Movie S3). Cells move from fields with coating Fibronectin density,

Force Balance at the Leading Edge, Force-Dependent Polymerization, and Cooperative Adhesion Determine the Adhesion–Velocity Relation.

In this section, we formulate a force balance at the leading edge in order to describe cell motion. Forces act on the cell across the whole area of contact with the substrate. They are coupled across the whole cell to the leading edge by tension (36, 484950–51) or by the F-actin network for those parts of the network which are mechanically continuous with the lamellipodium (52). On that basis, we can place our force balance at the leading edge without neglecting forces acting on different parts of the cell, including the lamella.

We focus on the steady motion, when average front and rear velocity of the cell are equal on areas with homogeneous Fibronectin density in this section. Fig. 2A shows the forces acting at the leading edge of the cell. Each individual filament pushes with its force

The extension velocity

The basic thermodynamic relation Eq. 1 and the force balance Eq. 3 determine the cell velocity

Binding of a ligand to integrin is one of the most important ways how cells sense their environment. The binding event is input to a complex signaling network (27, 34, 57, 58). The signaling state of related pathways—e.g., Rho signaling to stress fibers (27, 57, 5960–61) or Rac signaling to FAs (25, 59, 6263–64) and other systems (656667–68)—and force-, flow-, and myosin-mediated feedbacks affect the density of adhesion structures (8, 20, 23, 31, 60, 69707172–73), interact with integrin signaling, and thus shape the relations between

According to the basic ideas on the biphasic adhesion–velocity relation,

Analysis of the Adhesion–Velocity Relation.

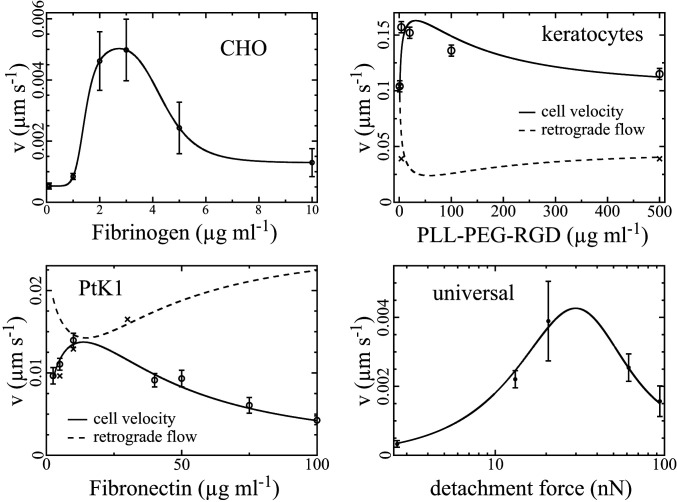

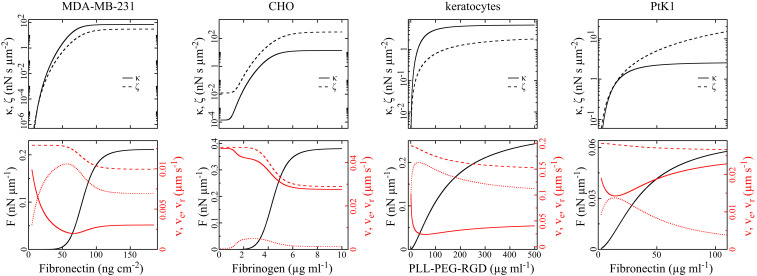

We analyze the adhesion–velocity relation by fitting Eqs. 4 and 5 to the measured data in Fig. 2B of the MDA-MB-231 dataset. The fit reproduces the relation, including the velocity maximum and the saturating behavior. The resulting parameters are listed in Table 1. We also include data from literature for keratocytes (33), PtK1 cells (31), and CHO cells (7) into the analysis (Figs. 3 and 4 and Table 1). We calculate the force

| Parameter | MDA-MB-231 | CHO | Keratocytes | PtK1 | Units |

| F-actin network extension Eq. 1 | |||||

| Force-free network-extension rate | 0.0156 | 0.057 | 0.197 | 0.030 | |

| Network depolymerization rate | 0.0027 | 0.010 | 0.0017 | 0.0016 | |

| Retrograde-flow friction coeff. | |||||

| Hill coefficient | 8.77 | 7.71 | 1.94 | 2.11 | |

| Half-max. value | 73.6 | 4.63 | 66.1 | 22.3 | |

| Max. value | 70.1 | 13.8 | 6.12 | 2.60 | nN |

| Membrane drag coefficient | |||||

| Hill coefficient | 7.59 | 7.53 | 1.36 | 1.53 | |

| Half-max. value | 85.7 | 5.33 | 218.6 | 382 | |

| Max. value | 30.8 | 296.0 | 2.86 | 117 | nN |

| Forces Eq.3 and SI Appendix, Eq. S8 | |||||

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | nN | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | nN | |

| 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.019 | 0.012 | nN |

The values g = 0.37579, gd/kBT = 248 nN−1, andN = 248 μm−1 (1777)SI Appendix, section S4 relates some parameter values to available published results. Coeff., coefficient; max., maximum.

The dependency of the cell velocity on the substrate ligand density in terms of the concentration of Fibrinogen in the coating solution for CHO cells (data from the

Predictions of Eqs. 2–5 with the parameters for the different cell types listed in Table 1 resulting from the fits of Eqs. 4 and 5 to experimental data shown in Figs. 2B and 3. (Upper) Retrograde-flow velocity friction coefficient

Keratocytes offer the best opportunity for relating our results to prior knowledge, since they are the best-studied cell type among our examples. The forces occurring in keratocyte migration on coating densities covered by the experiments are in the same range (Fig. 4) as the forces of the dynamic (1415–16) and predicted stationary force–velocity relation (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), and are in agreement with experimental and theoretical analyses of membrane tension in moving keratocytes (80). Keratocytes exhibit

Forces.

Interestingly, fitting reveals that both velocity-independent forces vanish,

The force

PtK1 and CHO cells with

We find both stronger effects of adhesion on protrusion force at the front

The relations between the ligand density

The values of

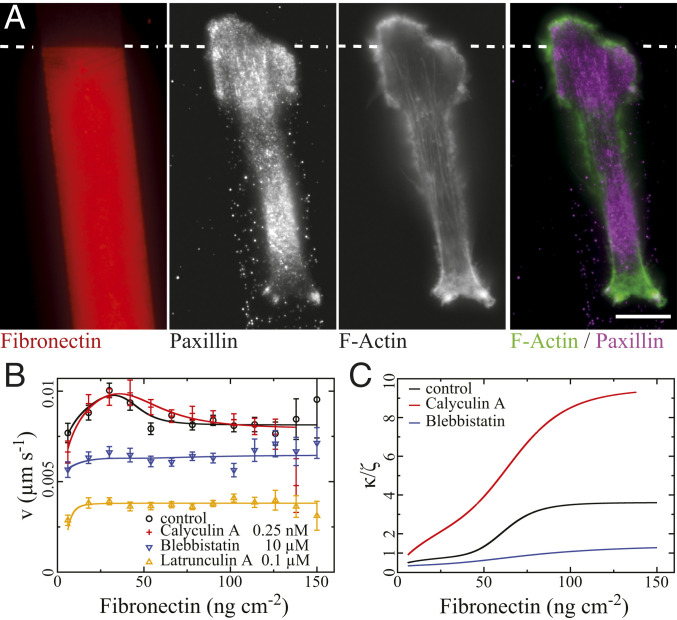

F-actin, adhesion sites, and effects of inhibitors in MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Fixed cell on a Fibronectin step (moving up, 8 to 40 ng

Our fitting results show rather strong positive feedback in the pathway from integrin to adhesion structures in MDA-MB-231 and CHO cells (values of

We learn more about the positive feedback by applying Blebbistatin, Calyculin A, or Latrunculin A. Blebbistatin inhibits myosin II activity. Its application (10

Calyculin A amplifies myosin II activity. Its application (0.25 nM) caused a broader maximum of the velocity (Fig. 5C). This shape of the relation entails a decrease of

Latrunculin A inhibits F-actin polymerization. Its application (0.1

Fibronectin Density Steps Reveal Spring-Like Interaction of Front and Rear.

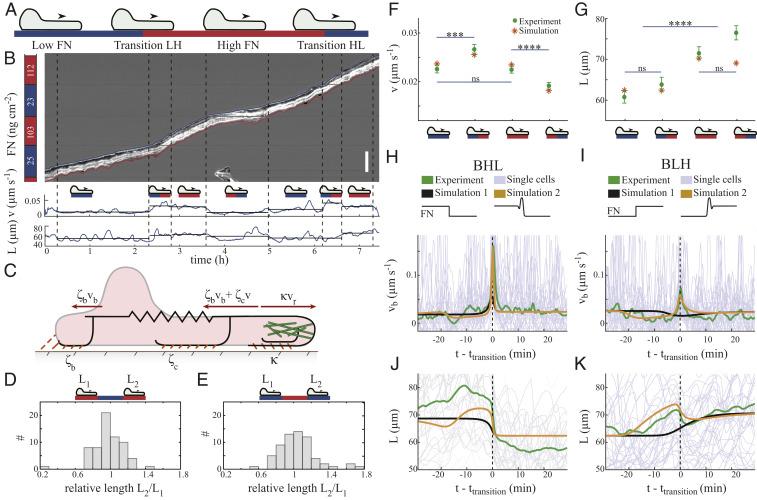

We have considered steady motion of cells on homogeneous Fibronectin density so far. Characterizing the mechanical properties of the front–rear interaction requires perturbations of the motion on homogeneous coating, as given by the transitions between different Fibronectin densities (Fig. 6 A and B). Cell front and rear see different ligand densities during transitions between density fields (Fig. 6A). The velocity of the cell in Fig. 6B increases when its front part enters a region with high adhesion density and slightly decreases when its rear part also reaches the high-Fibronectin region (Fig. 6 A and B). When the cell enters a region with low Fibronectin density, it shows the opposite behavior with decreased velocity during the transition and an increase when the transition is completed (Fig. 6 A and B). This directly confirms the idea that strong adhesion at the front supports motion, and strong adhesion at the back resists motion.

Perturbation of steady motion at Fibronectin density steps. (A) We distinguish phases where cells are completely on one density segment, and transition phases where cell front and back are on different densities. FN, Fibronectin. (B) Kymograph of a cell running through areas of different Fibronectin densities (given on the left). We trace front (blue) and back (red) and provide the time course of front velocity (v) and cell length (L). Mean velocities and mean lengths are indicated by horizontal lines for each phase. (Scale bar: 100

Kymographs of another set of measurements with 20-s time resolution show that the front is moving rather smoothly and changes its velocity at the Fibronectin density steps (Fig. 6B and Movie S4). The rear motion exhibits larger fluctuations and can even form a transient protrusion extending backward. We consider the front velocity

We need to look closer at the force-resisting motion to understand the differential behavior of

We start our experimental investigations on the nature of the front–rear coupling with the question for an intrinsic Fibronectin-related cell length. If it exists, the cell length should mainly be set by the Fibronectin density

The elastic force

The behavior of the cell length

The biphasic character of the adhesion–velocity relation and cell variability entail a qualitative difference between two groups of cells with respect to the velocity behavior. Some cells moving across the density regions in a given experiment are in the rising phase of the adhesion–velocity relation and exhibit a smaller velocity

The dynamic behavior during transitions between density regions shows qualitative differences of front versus back of the cell. The mean velocity of the front adapts quickly to the values set by the adhesion–velocity relation (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). During transitions of the front, the back velocity does not change dramatically, but follows the trend of the front velocity (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). In contrast,

During BHL transitions, the average length of the cell shows a sudden drop (Fig. 6J), which corresponds to the peak of

We quantify the elastic modulus

Discussion

We fabricated patterned Fibronectin lanes with well-defined steps in coating density by two-step microcontact printing and used them to study how adhesion acts on the balance of forces promoting and resisting motion, how forces are transmitted between cell front and rear, and how cells adapt their migration behavior to varying surface adhesiveness.

In the first part of the study, we used the biphasic adhesion–velocity relation to investigate force-generation mechanisms. In particular, our results from the analysis of cell transitions between different Fibronectin densities confirm the idea of adhesion-promoted pushing forces and adhesion-promoted forces resisting motion, which has been established in a variety of studies (6789–10, 24, 31, 35, 36). We are interested in the mechanism exploiting these forces for velocity control. The forces related directly to adhesion are traction forces, which form a dipole of opposing forces acting on the substrate (93, 94). Spread or moving cells adhered to the substrate exert forces in the range of 100 nN (95) or tension in the kilopascal range (24, 93, 9697–98).

The forces controlling velocities appear to be much smaller. Our results (Fig. 4), direct force measurements (1415–16), and membrane-tension measurements (80, 99) show forces related to motion acting on the cell membrane in the range of 0.1 nN

With the mechanism our results support, it is not contractile tension that controls the velocity, but adhesion-controlled friction forces, which are three orders of magnitude smaller. The force generated by polymerization at the leading edge is transmitted to the substrate as a friction force in the lamellipodium and the lamella–lamellipodium transition zone. It is the force required to drive the retrograde flow of the F-actin network against friction in these regions. This idea is in agreement with the picture of a molecular clutch (19) and results on the dynamic force–velocity relation of lamellipodial protrusion (16). Retrograde flow in the lamella is driven by myosin (20, 25, 31, 101). Lamella flow also transmits traction stress to the substrate (25). If this stress is in the direction of retrograde flow, as in PtK1 cells, it also generates protrusive force (25).

Our results suggest that the protrusive forces generated in lamellipodium and lamella speed up cell motion in the rising phase of the adhesion–velocity relation, since the density of adhesion structures increases with the Fibronectin density, thus increasing friction and

Application of Blebbistatin and Calyculin A has provided some insight into the role of myosin II in the mechanism of force generation. Traction stress under the lamella is substantially smaller than control upon Blebbistatin application (25). However, the leading edge still protrudes with suppressed myosin II activity (20); fibroblasts, CHO cells, and keratocytes still move (100, 103, 104); spreading continues (101) or speeds up (105); and Gardel et al. (25) find actin-polymerization forces in the lamellipodium to be sufficient to generate traction and mediate leading-edge protrusion independent of myosin II activity in PtK1 cells. The cell velocity might even increase upon Blebbistatin application (106, 107). Suppression of polymerization by cytochalasin D stops retrograde flow in the lamellipodium and stops protrusion 20, 25, (31, 101), and the leading edge retracts toward larger adhesion structures (20, 101). Thus, motion with substantially reduced myosin II activity, retrograde flow, and traction transmission to the substrate in the lamella is possible, but motion without polymerization in the lamellipodium is not. At the same time, application of Blebbistatin decreases velocities and abolishes the biphasic character of the adhesion–velocity relation with MDA-MB-231 cells (Fig. 5C), PtK1 cells (31), and keratocytes (33). Amplifying myosin activity by Calyculin A entailed biphasic relations with higher velocity than control (Fig. 5C) (31, 33).

Partial understanding of this role of myosin II arises from an observation by Gupton and Waterman-Storer (31) on an effect of myosin II besides driving lamella flow by contraction. The density of adhesion structures decreased upon Blebbistatin application and increased upon Calyculin A application in PtK1 cells, i.e., myosin acts to a substantial part via its effect on adhesion structure density [also in other cell types (106, 107)]. That means it shapes the dependency of

We can conclude two aspects of the role of myosin II for the cell velocity from these considerations. Velocity-independent forces generated by myosin II—e.g., in stress fibers—balance and do not affect the cell velocity. Myosin II affects the density of adhesion structures and, thus, velocity-dependent friction forces via the friction coefficient and, thus, affects cell velocity. If that effect of myosin II tilts the balance toward

Myosin also drives lamellar flow, causing friction forces via the flow velocity. However, we cannot individually quantify the contribution of this flow since we cannot separate it out of the total protrusive force. If lamella and lamellipodium are mechanically continuous, forces generated in the lamella are transmitted to the leading edge by affecting

The leading-edge force balance with our mechanism is

It has been argued before that a gradient of adhesion strength from strong at the front to weak at the back is required for motion (37, 38). Motion arises from contraction as a tug of war between strong and weak adhesion sites mediated by stress fibers in that picture, with the strong adhesions pulling off the weak ones and, thus, the cell forward. We find cells that move straight from one density range to the next one, even for large Fibronectin density steps, and both from low to high and from high to low densities. If front and back of the cell were in a tug of war, we would expect a limit in the difference of density allowing for high–low transitions where the net force is balanced, and cell migration would stop. However, we did not find such a limit within step heights up to 90 ng

Our results are in line with the ideas summarized by Munevar et al. (24) by the term frontal towing model, which identifies asymmetric force generation as the cause of motion based on traction stress measurements. The force balance

Cells can move in heterogeneous environments with very adhesive and less adhesive regions in that way without getting stuck in the highly adhesive spots. If velocity-independent forces would contribute to the force balance, cell motion would start only beyond a critical retrograde flow

The ideas presented in this study supplement earlier studies on the pathways controlling F-actin density, myosin activation, and other feedbacks by a more mechanical view on the adhesion–velocity relation. The restriction to one-dimensional Fibronectin lanes presents itself as rewarding for the mechanistic study of this relation. Defined steps between different Fibronectin densities enable measurement of velocity and length adaptation and provide insights into the interaction between front and rear. The mathematical adhesion–velocity relation yields insights into the mechanism of velocity control by ligand density on the substrate. The relation holds for various cell types operating in different force regimes. It provides a quantitative mathematical framework for future studies on the relation of adhesion and the intracellular processes relevant for migration.

Materials and Methods

A detailed explanation of the materials and methods can be found in SI Appendix. It contains the protocols for micropatterning, Fibronectin-density measurements, cell culture, immunostaining, time-lapse microscopy, and image analysis.

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Rottner and J. Renkawitz for useful comments; T. Betz for providing cell lines; and C. Leu for the preparation of wafers. This work was supported by a grant from the German Science Foundation (DFG) through the Collaborative Research Center 1032 Project B01 (to J.O.R.); and DFG Gant FA 350/11-1 (to M.F.).

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

29

30

31

32

33

35

37

38

39

40

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

On the adhesion–velocity relation and length adaptation of motile cells on stepped fibronectin lanes

On the adhesion–velocity relation and length adaptation of motile cells on stepped fibronectin lanes