Contributed by Subra Suresh, February 8, 2021 (sent for review January 21, 2021; reviewed by José-Alain Sahel and M. Taher A. Saif)

Author contributions: S.C., H.L., M.D., G.E.K., and S.S. designed research; S.C., H.L., F.Z., and F.K. performed research; S.C., H.L., F.Z., F.K., M.D., G.E.K., and S.S. analyzed data; S.C., H.L., F.Z., F.K., M.D., G.E.K., and S.S. wrote the paper; and M.D., G.E.K., and S.S. supervised research.

Reviewers: J.-A.S., University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine; and M.T.A.S., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

1S.C., H.L., and F.Z. contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

Microfluidics is an important in vitro platform to gain insights into mechanics of blood flow and mechanisms of pathophysiology of human diseases. Extraction of 3D fields in microfluidics with dense cell suspensions remains a formidable challenge. We present artificial-intelligence velocimetry (AIV) as a general platform to determine 3D flow fields and a microaneurysm-on-a-chip to simulate blood flow in microaneurysms in patients with diabetic retinopathy. AIV is built on physics-informed neural networks that integrate seamlessly 2D images from microfluidic experiments or in vivo observations with physical laws to estimate full 3D velocity and stress fields. AIV could be integrated into imaging technologies to automatically infer key hemodynamic metrics from in vivo and in vitro biomedical images.

Understanding the mechanics of blood flow is necessary for developing insights into mechanisms of physiology and vascular diseases in microcirculation. Given the limitations of technologies available for assessing in vivo flow fields, in vitro methods based on traditional microfluidic platforms have been developed to mimic physiological conditions. However, existing methods lack the capability to provide accurate assessment of these flow fields, particularly in vessels with complex geometries. Conventional approaches to quantify flow fields rely either on analyzing only visual images or on enforcing underlying physics without considering visualization data, which could compromise accuracy of predictions. Here, we present artificial-intelligence velocimetry (AIV) to quantify velocity and stress fields of blood flow by integrating the imaging data with underlying physics using physics-informed neural networks. We demonstrate the capability of AIV by quantifying hemodynamics in microchannels designed to mimic saccular-shaped microaneurysms (microaneurysm-on-a-chip, or MAOAC), which signify common manifestations of diabetic retinopathy, a leading cause of vision loss from blood-vessel damage in the retina in diabetic patients. We show that AIV can, without any a priori knowledge of the inlet and outlet boundary conditions, infer the two-dimensional (2D) flow fields from a sequence of 2D images of blood flow in MAOAC, but also can infer three-dimensional (3D) flow fields using only 2D images, thanks to the encoded physics laws. AIV provides a unique paradigm that seamlessly integrates images, experimental data, and underlying physics using neural networks to automatically analyze experimental data and infer key hemodynamic indicators that assess vascular injury.

Human blood, primarily comprising plasma, red blood cells (RBCs), white blood cells, and platelets, is a non-Newtonian fluid exhibiting shear-thinning behavior (1, 2). The effect of this non-Newtonian behavior becomes more pronounced in microcirculation (3). Understanding and quantifying the biorheology of blood is essential for gaining insights into the mechanisms that influence microcirculation in physiology and disease (45–6). The characteristics of hemodynamics also determine the vascular integrity and blood-cell transport in physiology, e.g., the margination of platelets (7, 8). Platelet margination refers to the phenomenon of formation of a cell-free layer near the vessel wall in blood flow, as RBCs accumulate in the center of the vessel. Compromised hemodynamics can result in pathologies such as endothelial-cell inflammation and dysfunction, undesired platelet activation, and the formation of clots within a blood vessel (910–11).

Scientific research over the past several decades has led to rapid advances in in vivo imaging techniques (1213–14). Despite this progress, it is currently not feasible to observe in real time many in vivo biological processes in microcirculation, such as the rupture of a microaneurysm (MA) in the retinal microvasculature and the initiation and development of blood clots. To compensate for this void in our ability to track the origins and progression of disease states, in vitro experiments of blood flow within microfluidic channels have been developed to mimic in vivo circulation under both physiologically and pathologically relevant conditions (see reviews in refs. 1516–17). Microfluidic devices and laboratory-on-a-chip platforms offer advantages in exploring the biophysical and biochemical characteristics of blood flow in microvessels. Benefits of these devices include the need for only small volumes of blood for analysis and precise control over temperature, concentrations of gas, and chemicals in the blood (18). Another distinct advantage of such microfluidic platforms is that they enable quantitative determination of various key parameters associated with hemodynamics, such as spatial distributions of velocity and stress fields, under well-controlled experimental conditions so that mechanistic insights could be extracted for transitions from healthy to pathological states.

A wide variety of experimental techniques are currently available to assess the hemodynamics of in vitro blood flow in microcirculation. The state-of-the-art optical whole-field velocity measurement technique is microparticle image velocimetry (PIV) (19, 20), a nonintrusive method used to estimate flow fields in microchannels. Various algorithms employing

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models have also been employed to simulate blood flow in microvessels or channels to investigate the pathophysiology of circulatory diseases (37, 38). By invoking laws of physics (e.g., Navier–Stokes equations) and specific boundary conditions (such as no-slip conditions at the blood-vessel wall), CFD models can simulate the flow field and extract key hemodynamic indicators. Several studies have employed CFD models to compute flow and stress fields in normal microvessels, as well as channels with various shapes, such as stenotic channels [in which constricted flow from plaques markedly alters flow characteristics (39, 40)], aneurysmal vessels containing a bulge in the vessel as a result of a weakened vessel wall (41, 42), and other vasculatures with complex geometries (43, 44). However, results extracted from CFD models are very sensitive to the flow-boundary conditions assumed at the inlets and outlets, which can be patient-specific. Even moderate errors in flow-boundary conditions could lead to large uncertainty in the estimation of the flow fields (45). In addition, CFD simulations could be computationally cumbersome for modeling flow field with moving boundaries or geometric variation, such as the hemodynamics changes due to accumulation of blood cells.

Problem Description

Accurate assessment of hemodynamics in microvessels requires both experimental data extracted from controlled in vitro or in vivo assays and application of relevant laws of physics. In this work, we propose artificial-intelligence velocimetry (AIV), a unique computational framework that infers velocity fields and stress fields from two-dimensional (2D) images that are interpreted by using artificial-intelligence techniques based on underlying physical principles. In particular, AIV is developed based on the physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) (47, 48), which can automatically infer these flow fields in arbitrary domains by seamlessly integrating data from in vivo or in vitro with the governing equations of fluid flow. As illustrated in Fig. 1, with spatial coordinates and time,

![Schematic diagram of AIV. A fully connected neural network is used to approximate solutions to desired output parameters, (I,u,v,w,p), by considering space and time coordinates as inputs (x, y, z, t). The governing equations are encoded in the network, where the derivatives are computed via automatic differentiation in the TensorFlow code [Google (46)]. No-slip boundary conditions on the channel surfaces (including upper, lower, and lateral walls) are also introduced, namely, u(∂Ω)=0. The activation function for each neuron is σ(⋅)=sin(⋅). The parameters of the neural network are trained by minimizing the loss function, which is composed of three terms: data mismatch, wall boundary conditions, and residuals of all conservation laws. More details of the proposed framework are described in Materials and Methods and SI Appendix.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766004591834-b628a6fd-fbbb-48c0-858c-015bc3acc2a0/assets/pnas.2100697118fig01.jpg)

Schematic diagram of AIV. A fully connected neural network is used to approximate solutions to desired output parameters,

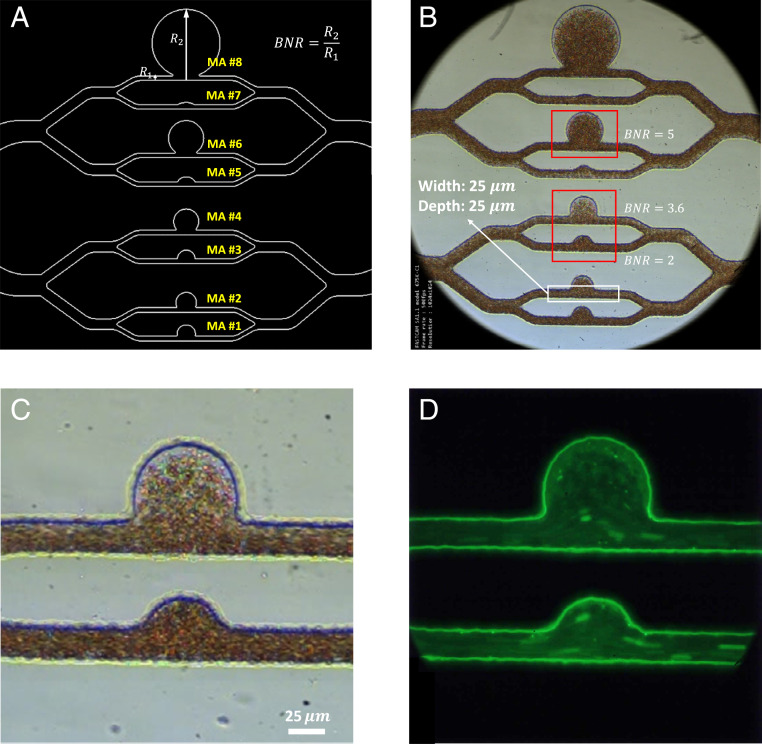

Design and microscopic images of the microfluidic platform, MAOAC. (A) Schematic diagram of the MA PDMS channels with different sizes. The size of the MA is characterized by the BNR, which is defined as the largest dimension of the MA body (

To demonstrate the capability of AIV based on a sequence of 2D microscopic blood-flow images, we first apply it to infer the velocity and stress fields in three-dimensional (3D) microchannels. As shown in Fig. 2 A and B, we design a microfluidic system, termed Micro-Aneurysm-On-A-Chip (MAOAC), to mimic MAs, which are the earliest clinically visible signs of diabetic retinopathy (DR), a complication of diabetes that could lead to visual impairment and blindness in diabetic patients (53). MAOAC contains eight straight microchannels intersecting with various sizes of cavities to mimic saccular-shaped MAs, the most prevalent shape of MAs observed in the retinal microvasculature of DR patients (54, 55). A high-speed camera is used to record blood flow in the microchannel (Fig. 2C). In addition, laser-induced fluorescence is employed to track the motion of platelets (Fig. 2D). More details of the experimental setup can be found in Materials and Methods. We adopt AIV to quantify key indicators of hemodynamics, such as velocity profiles, pressure, and wall shear stress, for various MAs and investigate alterations in hemodynamics induced by the change in size of MAs. In order to evaluate the performance of AIV, we compare the results from AIV with those obtained from five different experimental and computational methods: optical flow (36), Deep-PIV (56), single-cell tracking, CFD (57), and DPD (58).

Results

Inferring 2D Flow Fields.

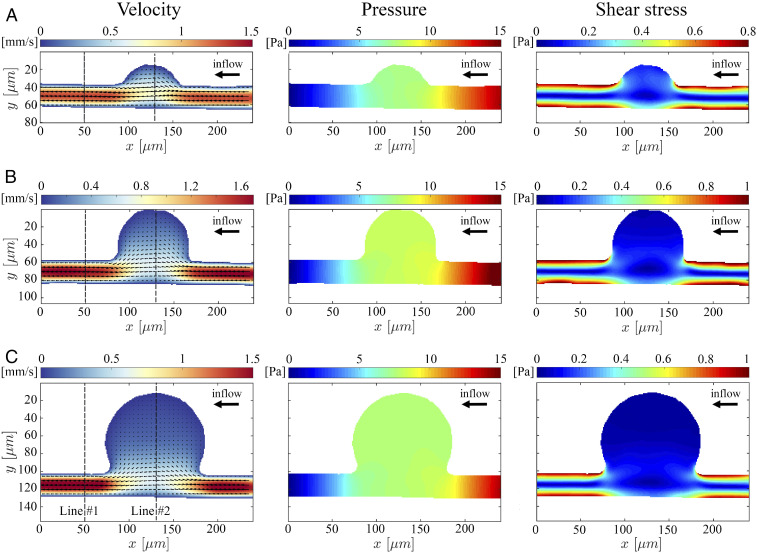

To demonstrate the capability of AIV to quantify the velocity and stress fields from microfluidic images during blood flow, we first extract 2D flow fields, such as velocity profile, pressure, and wall shear stress, from a sequence of 2D images taken in MAOAC and obtain the critical hemodynamic metrics. As shown in Fig. 2B, we select sequential images from three channels (MA

The 2D AIV predictions of velocity, pressure, and shear stress fields in MAOAC channels for BNR = 2 (A), BNR = 3.6 (B), and BNR = 5 (C). In Left, the arrows indicate the direction of the flow, whereas the color represents the magnitude of the velocity. AIV results are averaged over 100 image frames. The spatial distribution of the fields is represented by the colors in all of the plots.

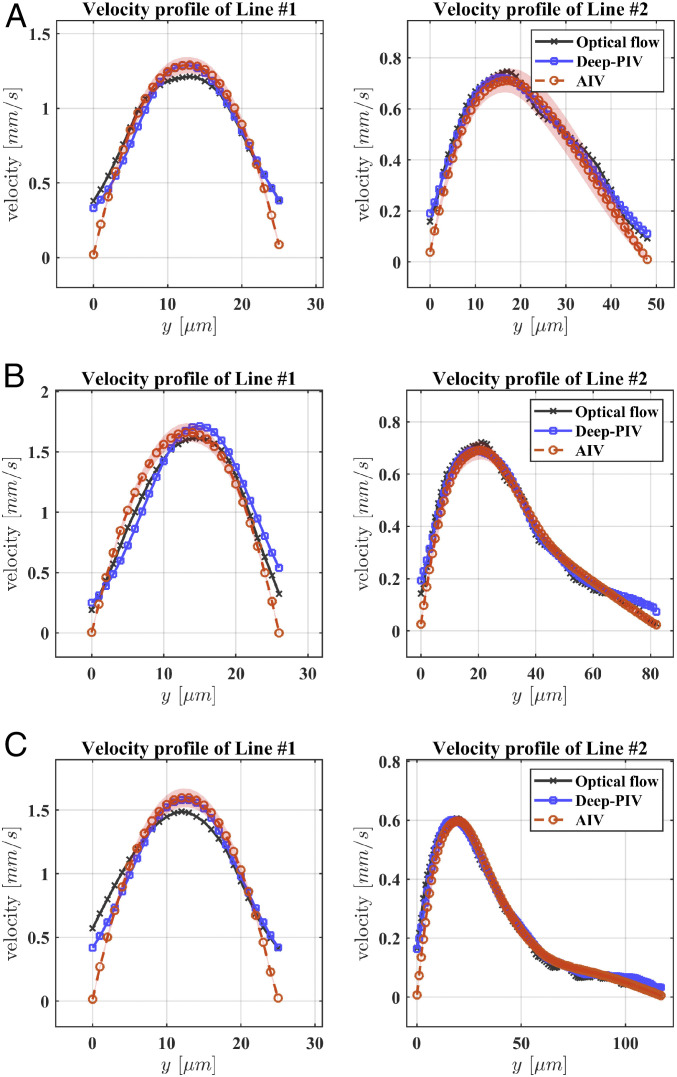

To further assess the reliability and accuracy of AIV, we compare our estimates with results obtained from three other independent approaches: the conventional optical flow method (36), Deep-PIV [an advanced PIV method with convolutional neural networks (32, 56)], and manual platelet tracking using the fluorescent images in our experiments. The implementation of the optical flow and Deep-PIV methods for predicting the fields in the present geometrical arrangements is described in SI Appendix. The velocity comparisons shown in Fig. 4 are performed at two points along vertical cross-lines of the microchannels: one located at the postaneurysm channel (Line #1, at

Comparison of the velocity profiles predicted by AIV, conventional optical flow, and Deep-PIV along two cross-lines in MAOAC channels with BNR = 2 (A), BNR = 3.6 (B), BNR = 5 (C). Comparisons are performed along two dotted lines marked at Fig. 3, Left. Line #1 is selected at the outlet portion of the microchannel, whereas Line #2 crosses the deepest region of the MAs. The symbols representing AIV predictions signify time-averaged values from 100 image frames, and the shadows represent SDs.

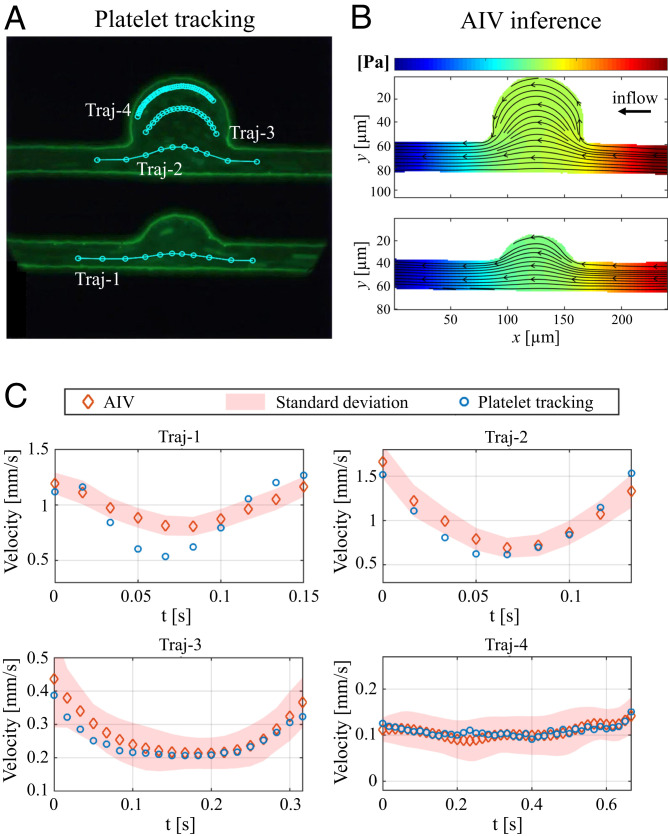

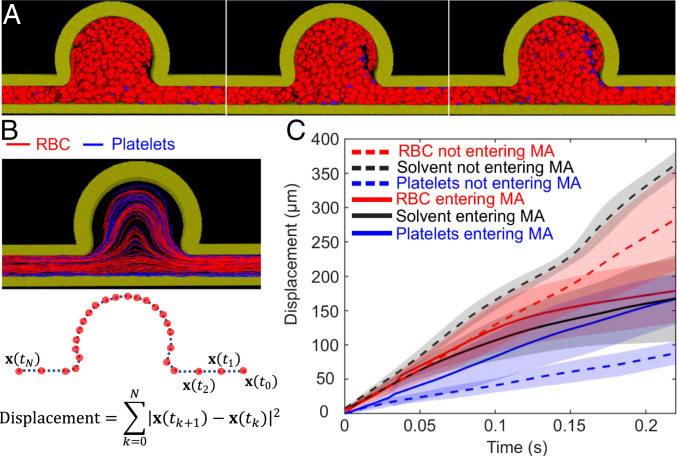

In addition to the above comparisons, we also performed a cross-validation of AIV by manually tracking the motion of platelets from fluorescence-stained video. As shown in Fig. 5A, four trajectories are identified for tracking the motion of four different platelets or platelet aggregates, with platelet velocities calculated along each of these trajectories. We also extract flow velocities along the same trajectories from velocity fields estimated by AIV in Fig. 5B for further comparison. To rationalize our approximation of local flow velocities using platelet velocities, we performed dissipative particle dynamics (DPD) simulations to model the transport of RBCs and platelets in channel MA#4 (BNR = 3.6), as shown in Fig. 6A. (Details of DPD simulation can be found in SI Appendix.) The trajectories of RBCs and platelets in Fig. 6B illustrate that in the straight channel, RBCs mostly travel in the core, where the flow velocity is high. This validates the assumptions, discussed earlier, that underlie our AIV framework. The platelets, however, flow in the cell-free layer near the vessel wall where the blood flow velocity is low, consistent with experimental and analytical studies (616263–64). As a result, the displacement of platelets in the straight channel (Fig. 6C) is much smaller than that of RBCs during the same time interval. On the other hand, Fig. 6 B and C also show that the trajectories of RBCs and platelets overlap in the MA and that their displacements are comparable during the same time interval. These observations suggest that the velocities of platelets can be used to approximate local blood-flow velocities when platelets move within MAs.

Comparison of the velocities predicted by AIV and platelet tracking along four platelet trajectories in two MAOAC channels with BNR = 2 and 3.6. (A) Four platelet trajectories are tracked by using video images capturing experiments with fluorescence-staining. The velocity is computed as

Simulation of RBC and platelet transport in MAOAC channel with BNR = 3.6. (A) Three sequential snapshots (from left to right) of RBCs and platelets traveling in the microchannel. Red, RBCs; blue, platelets. Solvent particles are not plotted here to preserve clarity of presentation. (B) Trajectories of RBCs and platelets in the microchannel, as well as calculation of the displacements of RBCs and platelets based on their trajectories. Red curves, RBCs; blue curves, platelets. (C) Displacements of RBCs, platelets, and solvent particles as functions of time. The dotted lines signify displacements of RBCs, platelets, and solvent particles that do not travel into the MAs, whereas the solid lines designate the displacements of RBCs, platelets, and solvent particles that travel into the MAs. Each curve represents the average of 15 samples randomly selected from the simulation, except that the solvent particles which do not travel into the MAs were selected randomly around the centerline of the postaneurysm channel.

Velocity estimates along the four trajectories are plotted in Fig. 5C. These results show that the AIV predictions are in good agreement with velocities calculated from the two trajectories (Traj-3 and Traj-4) of platelets traveling in the MAs in channel MA#4. This demonstrates the capability of AIV to accurately infer flow fields in blood microcirculation. At platelet trajectories further away from the perimeter of the MA, such as those along Traj-1 and Traj-2, the differences between AIV (on RBC trajectories) and platelet tracking become more accentuated, as anticipated from the effect of platelet margination.

Extracting 3D Flow Field from 2D Images.

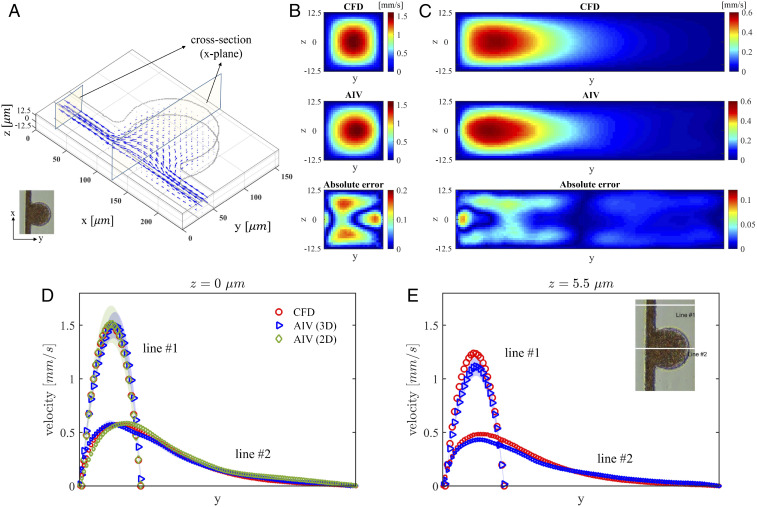

Next, we demonstrate that AIV can infer the full 3D flow velocity profiles along the entire depth of the microchannel using 2D images by invoking the underlying physical laws of fluid flow. Such estimation cannot be accomplished by using existing methods, such as Deep-PIV or optical flow, due to the lack of data at different depths of the channel. In order to obtain 3D velocity profiles, as shown in Fig. 7A, we extend our computational domain along the depth direction (

![The 3D AIV predictions for MAOAC channel with BNR = 5. (A) A 3D computational domain is constructed by extending the 2D domain along the depth direction (z) by 25 μm (z∈[−12.5,12.5]

μm), consistent with the depth of the MAOAC channels. The images capture the motion of RBCs at the middle plane of the channel depth direction (z=0). (B and C) Velocity (B) and pressure fields (C) at three different cross-sections (z=0,±7.5

μm) along the depth of the channel. (D) Shear stress on the channel wall. AIV results are averaged over 100 image frames.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766004591834-b628a6fd-fbbb-48c0-858c-015bc3acc2a0/assets/pnas.2100697118fig07.jpg)

The 3D AIV predictions for MAOAC channel with BNR = 5. (A) A 3D computational domain is constructed by extending the 2D domain along the depth direction (

Fig. 7 B and C illustrate the velocity and pressure fields inferred by the AIV model at three different depth positions of the MA#6 channel (BNR = 5): z = 0 (middle plane) and z =

To evaluate the 3D results from AIV, we perform a companion 3D CFD simulation using the same governing equations (Eq. 2 in Materials and Methods) and computational domain as in the AIV method. We also employ the Carreau–Yasuda rheology model (Eq. 3) to capture the shear-thinning behavior of the blood. The governing equations are solved by using

Comparison of 3D AIV predictions with results of CFD simulations for the MAOAC channel with BNR = 5. (A) The 3D velocity vectors inferred from AIV. Two cross-sections along the x axis are selected for comparison with CFD simulations. (B) Velocity at the cross-section located at

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

In this work, we have developed a unique model to determine the 3D velocity, pressure, and stress fields associated with human blood flow in microcirculation by synergistically integrating the underlying physics with sequential images from microfluidics experiment and machine learning. The advantage of the proposed AIV model is that the conservation laws of the physics of blood flow and no-slip boundary conditions are encoded into a deep-learning neural network to interpret direct experimental observations from a microfluidics platform. We note that the flow velocity boundary conditions (slip or nonslip) on the channel wall in AIV can be specified by the user, depending on the particular case of interest. Therefore, the predictions of near-wall velocity by AIV are more physiologically relevant than those measured from optical flow and

To validate the present approach, we compare the predictions of AIV models on the full spectrum of key hemodynamic parameters, such as pressure differential, shear rate, and wall shear stress, with results obtained from five different experimental and computational methods: optical flow (36), Deep-PIV (56), single cell tracking, CFD simulations (57), and DPD (58). Our results show that AIV predictions of bulk flow velocities in MAOAC with different geometries are in agreement with results from these other independent methods. In contrast to CFD models, AIV is capable of inferring flow field on-the-fly in microchannels because of its flexibility to incorporate data from sequential experimental images, particularly with fluids, such as blood, with a heterogeneous composition. On the other hand, we demonstrate that AIV can infer, owing to the encoded physics laws, full 3D flow fields along the depth of the microchannel from a sequence of 2D images. This is difficult to achieve with conventional

The present experimental results also provide insights and quantitative details to rationalize a variety of clinical findings pertaining to MAs in DR. The predictions of the flow field using MAOAC and AIV show reduced flow velocity and wall shear stress in the MAs with different BNR. Particularly, as the BNR of the MAs increases, the decrease in shear stress near the channel wall of the MAs becomes more significant. These results provide a rationale for the clinical finding that endothelial dysfunction, which is manifested as increased von Willebrand factor expression on the endothelial cell, is more likely to occur in MAs with larger BNR due to the reduced wall shear stress (59). We note that AIV can assess the blood-flow velocity for different shapes of MAs, such as focal bulging, fusiform, mixed saccular/fusiform, and so on. In this paper, we designed the microchannels to mimic various sizes of saccular-shaped MAs, because they are the most prevalent shape of MAs observed in the retinal microvasculature of DR patients. Future studies could employ additional microfluidic geometry designs to address different types of MAs.

The altered hemodynamics in MAs also contributes to thrombosis in the vascular lumen of MAs, a recently documented pathology of DR (42). In vivo images obtained from AOSLO have been used to classify the MAs’ morphologies into different groups (54), as well as to detect the blood clotting inside MAs (42). The AIV model can potentially be used to interpret the AOSLO images and predict the thrombus formation or rupture of MAs by monitoring the key hemodynamic metrics, such as wall shear stress, which is associated with the inflammation and dysfunction of endothelium cell, as well as the shear rate and the platelet residence time in the MAs, which can be used to predict the platelet activation and aggregation. We note that quantification of hemodynamic parameters from in vivo measurements in previous studies (42, 59, 65) were performed by using CFD models with assumed and general inflow and outflow boundary conditions since patient-specific inflow velocity was not readily available from in vivo images. The present AIV model, which does not require implementation of flow boundary conditions and mesh generation, can potentially learn the flow fields directly from in vivo video images and provide more accurate evaluation of hemodynamic indicators.

The AIV model proposed in this work can also be extended to accommodate various data sources through a multifidelity (MF) framework (69, 70), where additional neural networks are used to learn the correlation between the low-fidelity (e.g., simulation) and high-fidelity (e.g., experimental) data. The MF framework is very effective when there is a dearth of reliable, high-fidelity data and, thus, could be particularly useful for learning from in vivo images whose resolution and quality may be limited. For example, when only a portion of the flow field can be observed from in vivo images or only measurements of the velocity along a limited set of trajectories are available (e.g., by tracking local displacements of blood cells), we could first perform 3D CFD simulations to evaluate the flow field. These simulation data are considered low-fidelity data, as they are sensitive to the inflow and outflow boundary conditions, which are not always available from in vivo measurements. Following this, the 3D simulation data (low fidelity) could be integrated with the partial velocity field estimated by AIV based on in vivo images (high fidelity) using the MF framework to predict the entire flow field.

Although we have demonstrated several advantages of AIV over conventional methods, we also note some limitations of the AIV model. First, the computational cost of training the AIV model could be higher than the cost of optical flow or

In summary, we present AIV, a unique platform that is capable of automatically inferring blood-flow field in microfluidic channels, and compute key hemodynamic parameters that are associated with the pathophysiology of MAs, one of the earliest clinically visible signs of DR. Encoded with physical laws and constitutive equations and integrated with neural-network training algorithms, AIV performs more effectively compared to the existing methods, particularly when the experimental data are limited. AIV also incorporates data from visual images, which is particularly important for investigation of blood flow (i.e., flow of RBCs and other blood components such as platelets) under pathological conditions where reliable constitutive laws may not be able to accurately describe hematological properties of blood for patient-specific disease states. AIV also can potentially facilitate scientific research in laboratories where systematic experiments alone, even with advanced tools, may not be sufficient to quantify all of the key parameters responsible for the pathogenesis of vascular injury. With continuous training, AIV offers a potentially powerful pathway to infer hemodynamics from in vivo examination and to develop quantitative metrics for patient diagnosis and monitoring.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Setup.

MA PDMS channel fabrication.

As illustrated in Fig. 2 A and B, eight microchannels that contain various sizes of cavities are designed to mimic different MAs. The BNR of the simulated MAs is defined as the largest caliber of the MA body divided by the size of feeding vessels and varies from 12 to 1.5. These MA channels were fabricated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) using standard soft lithography. Each device was fabricated by using a master mold, lithographically patterned with SU-8 negative photoresist (Microchem Corporation) on a 4-inch silicon wafer (Silicon Connection), which was later placed inside a Petri dish. Commercial thermocurable PDMS (Sylgard 184, Dowsil) prepolymer was prepared by mixing the base and curing agent at a 10:1 weight ratio, following which the PDMS prepolymers were degassed under vacuum and cast onto the mold. Thermal cross-linking of PDMS was performed by curing at 80 °C for 2 h. The cured PDMS was cut and peeled off from the channel mold, following which the inlet and outlet access ports were created by using a 1.5-mm-diameter punch. Next, the PDMS channel was bonded with a cover slide under 80 °C for 2 h. Experiments were conducted after plasma pretreatment for 1 min.

Sample preparation.

Peripheral blood was drawn from a healthy donor by Venipuncture into a K2E EDTA tube, after which the whole blood was centrifuged at 200 × g for 12 min to extract platelet-rich plasma (PRP). The upper layer of PRP was further centrifuged at 1,200 × g for 5 min to acquire platelets, which were washed three times with platelet-washing solution and then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline. The remaining blood cells were stored at 4 °C for later use. The platelets were then stained with DIOC6 (Sigma-Aldrich) (0.5

All procedures on peripheral blood specimens were approved and performed in accordance with the Singapore National Health Group Domain Specific Review Board (the central ethics committee) and mutually recognized by Nanyang Technological University Institutional Review Board (IRB#2018/00671). All blood specimens were de-identified prior to use in the experiment.

Microfluidics experiment and visualization.

The microfluidic device was installed on a Nikon Eclipse T2000-U (Nikon) and visualized under a 40× objective. A blood sample, 20

AIV Model.

Underlying physics laws.

To estimate the velocity and pressure fields from a sequence of images from microfluidic experiments (Fig. 2C), we follow the optical flow constraint (35), a basic assumption widely used in computer vision or fluid visualization. Here, it is assumed that the variation in the image brightness represents blood flow, and the image intensity is a spatiotemporal scalar field

Integrating physics with image data from microfluidic experiments using AIV.

The AIV technique employed here is based on PINNs, which were originally developed for solving forward and inverse problems for partial differential equations (47, 74) and were subsequently extended to solve fluid-mechanics problems (48, 7576–77). AIV is capable of seamlessly assimilating the Navier–Stokes equations and the experimental data, and thus allows for the extraction of velocity and pressure fields by considering both the underlying physics of blood flow and the microfluidics or in vivo image data. As shown in Fig. 1, AIV contains a fully connected neural network, which is used to approximate the solutions, i.e.,

Acknowledgements

S.C. and G.E.K. were supported by Department of Energy Physics-Informed Learning Machines Project No. DE-SC0019453. H.L., M.D., and G.E.K. were supported by NIH Grant R01HL154150. M.D. was supported by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology J-Clinic for Machine Learning and Health. F.K. and S.S. were supported by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, through the Distinguished University Professorship (S.S.).

Data Availability

The data and codes used in this manuscript are publicly available on GitHub (https://github.com/shengzesnail/AIV_MAOAC) (79).

References

2

3

4

5

6

7

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

Artificial intelligence velocimetry and microaneurysm-on-a-chip for three-dimensional analysis of blood flow in physiology and disease

Artificial intelligence velocimetry and microaneurysm-on-a-chip for three-dimensional analysis of blood flow in physiology and disease