Contributed by Stephen Polasky, October 12, 2020 (sent for review June 9, 2020; reviewed by Neville Crossman, Caroline Hattam, and Lars Hein)

Author contributions: K.A.B., L.A.G., S.P., Y.A.-T., P.H.S.B., F.D., M.E.M., N.V.N., H.P., L.J.S., U.B.S., and M.V. designed research; K.A.B., L.A.G., S.P., Y.A.-T., P.H.S.B., F.D., U.J., M.E.M., N.V.N., H.P., N.P.-M., L.J.S., U.B.S., E.S., and M.V. performed research; K.A.B., L.A.G., S.P., Y.A.-T., P.H.S.B., F.D., U.J., M.E.M., N.V.N., H.P., N.P.-M., L.J.S., U.B.S., E.S., and M.V. analyzed data; K.A.B., L.A.G., S.P., Y.A.-T., P.H.S.B., F.D., M.E.M., N.V.N., H.P., L.J.S., U.B.S., and M.V. wrote the paper; and K.A.B., L.A.G., and S.P. provided project administration and leadership.

Reviewers: N.C., Murray Darling Basin Authority; C.H., University of Plymouth; and L.H., Wageningen University.

- Altmetric

Understanding and tracking nature’s contributions to people provides critical feedback that can improve our ability to manage earth systems effectively, equitably, and sustainably. Declines in biodiversity and ecosystem functions over the past 50 y have decreased the ability of nature to contribute to quality of life. Changes in technology and adaptation in social systems has partially offset the negative impacts of environmental change on quality of life, but downward trends have still occurred for many categories of nature’s contributions.

Declining biodiversity and ecosystem functions put many of nature’s contributions to people at risk. We review and synthesize the scientific literature to assess 50-y global trends across a broad range of nature’s contributions. We distinguish among trends in potential and realized contributions of nature, as well as environmental conditions and the impacts of changes in nature on human quality of life. We find declining trends in the potential for nature to contribute in the majority of material, nonmaterial, and regulating contributions assessed. However, while the realized production of regulating contributions has decreased, realized production of agricultural and many material commodities has increased. Environmental declines negatively affect quality of life, but social adaptation and the availability of substitutes partially offset this decline for some of nature’s contributions. Adaptation and substitutes, however, are often imperfect and come at some cost. For many of the contributions of nature, we find differing trends across different countries and regions, income classes, and ethnic and social groups, reinforcing the argument for more consistent and equitable measurement.

Nature provides a wide range of contributions to human quality of life (1). From life support systems to spiritual and scientific inspiration, people have long worked with nature to enhance its benefits and tame its damages, from cultivating wild species to constructing drainage canals (1). Since the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2), efforts to identify, quantify, and protect the broad range of contributions, variously described as ecosystem services (2) and nature’s contributions to people (1), have reached far into the mainstream, embraced by governments, corporations, and philanthropic organizations (3). However, as evidence mounts that human activities are changing the earth system in unprecedented ways (4), systematic evidence documenting a related decline in nature’s contributions to human wellbeing has not been amassed in parallel (5)—whether a change in nature occurs is a related but distinct question from how that change impacts people.

The difficulty of clearly documenting the impacts of changes in the contribution of nature to quality of life has several interrelated causes. First, many of nature’s contributions to quality of life have complicated causal chains that are not fully understood and that may play out over large spatial or temporal scales (6), making it difficult to fully appreciate these contributions or to value them. Second, for nature’s contributions to be realized, inputs from nature are often combined with human labor and anthropogenic assets, which can make it difficult to disentangle the contributions of nature from those of other inputs (1). Third, substitutes exist for some, but not all, of nature’s contributions. For example, shifting demand to crops that are wind- rather than animal-pollinated can partially offset the impact of a decline in pollinators on food supply, investment in water-filtration technology can mitigate a decline in water quality, and aquaculture can offset declines in wild-caught fish. However, adaptation and alternatives typically come at some cost and may not be available for all of nature’s contributions, and the full importance of the contributions of nature may be recognized only when substitutes are exhausted (7). Despite these challenges, there is a large and growing literature documenting various aspects of the contributions of nature to people (8).

Here, we synthesize the scientific literature to assess global trends in nature’s contribution to human quality of life over the past 50 y, a period for which global data are more readily available and over which there has been rapid economic growth with large-scale impacts on nature around the world. Our scoping review (9, 10) was carried out as part of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) Global Assessment (1, 4, 8). IPBES defined 18 categories of nature’s contribution to people, which include regulating, material, and nonmaterial contributions (Table 1). Although many of nature’s contributions are positive, negative impacts, such as when elephants trample crops or mosquitos spread disease, are also considered.

| Nature’s contribution to people | Brief description | |

| Regulating | Habitat creation and maintenance | The formation and continued production of ecological conditions necessary or favorable for living beings important to people |

| Pollination and dispersal of seeds | Animal facilitation of pollen movement and seed dispersal of beneficial organisms | |

| Regulation of air quality | Filtration, fixation, degradation or storage of pollutants and gasses | |

| Regulation of climate | Emission and sequestration of greenhouse gases, biogenic volatile organic compounds, and aerosols; biophysical feedbacks (e.g., albedo, evapotranspiration) | |

| Regulation of ocean acidification | Regulation by photosynthetic organisms on land and sea of atmospheric CO2 concentrations and thus seawater pH | |

| Regulation of freshwater quantity | Regulation of the quantity, location, and timing of the flow of surface and groundwater | |

| Regulation of freshwater quality | Ecosystem filtration and addition of particles, pathogens, excess nutrients, and other chemicals | |

| Formation and protection of soils | Soil formation and long-term maintenance of soil fertility, including sediment retention and degradation or storage of pollutants | |

| Regulation of hazards and extreme events | Amelioration of the impacts of hazards; reduction of size or frequency of hazards | |

| Regulation of detrimental organisms | Regulation of pests, pathogens, predators, competitors, parasites, and potentially harmful organisms | |

| Material | Energy | Biomass-based fuels such as biofuel crops, animal waste, and fuelwood |

| Food and feed | Food and feed from wild, managed, or domesticated organisms from terrestrial, freshwater, and marine sources | |

| Materials and assistance | Cultivated or wild materials and direct use of living organisms for industrial, ornamental, company, transport, labor, and other uses | |

| Medicinal and genetic resources | Naturally derived medicinal materials; genes and genetic information | |

| Nonmaterial | Learning and inspiration | Capabilities developed through education, knowledge acquisition, and inspiration by nature for art and technological design |

| Experiences | Physically and psychologically beneficial activities, healing, relaxation, recreation, and aesthetic enjoyment based on contact with nature | |

| Supporting identities | The basis for religious, spiritual, and social cohesion; sense of place, purpose, belonging, or rootedness associated with the living world; narratives, myths, and rituals; satisfaction from a landscape, seascape, habitat, or species | |

| Maintenance of options | Capacity of nature to keep options open to support quality of life in the future | |

The table was adapted from ref. 1.

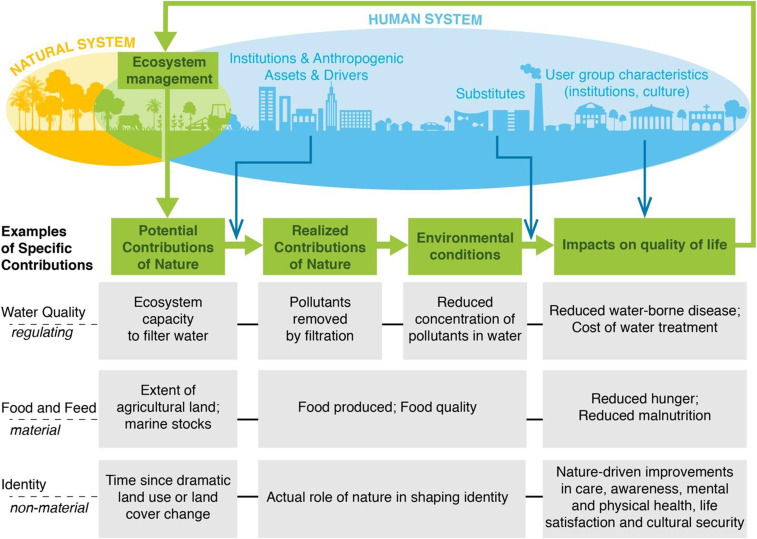

In characterizing global trends for these categories of contribution, we expand the logic chain linking nature to quality of life developed in several prior studies (111213–14). Our expansion defines four distinct but related aspects of nature’s contributions to people (Fig. 1). First, nature plays a role in providing functions that potentially contribute to human wellbeing. These potential contributions are diminished with the loss of biodiversity or ecosystem processes. Second, “realized contributions” occur when people experience the contributions of nature. Third, for some contributions, there is a difference between the realized contributions of nature and “environmental conditions,” with environmental conditions often reflecting external drivers, not the contributions of nature. For example, as pollution of air or water increases, nature may remove more of those pollutants and thus increase the realized contribution of filtration, until a point of saturation is reached. Even as filtration increases, however, environmental quality may decline because of increased pollution loading. Fourth, there is the “impact on quality of life,” which is ultimately the goal of assessing nature’s contributions. Distinguishing between these concepts can help to overcome ongoing confusion over use of terms in the scientific literature that has detracted from progress and led to lack of clarity in communication about nature’s contributions to people (15). Clearly distinguishing between potential contributions, realized contributions, environmental conditions, and impact on quality of life helps pinpoint the ways that changes in nature affect people and illuminates remaining knowledge gaps.

Differentiation of potential and realized contributions of nature, environmental conditions, and impact on quality of life. Nature, as altered by human management, generates potential contributions. The combination of potential along with human inputs leads to realized contributions of nature. For some types of contributions of nature, there is a difference between realized contributions and environmental conditions, because environmental conditions are influenced by additional factors such as human-caused pollution. Impacts on quality of life are further modulated by substitutes, institutions, and culture. Information about how nature’s contributions impact quality of life can be used to modify human management and inputs.

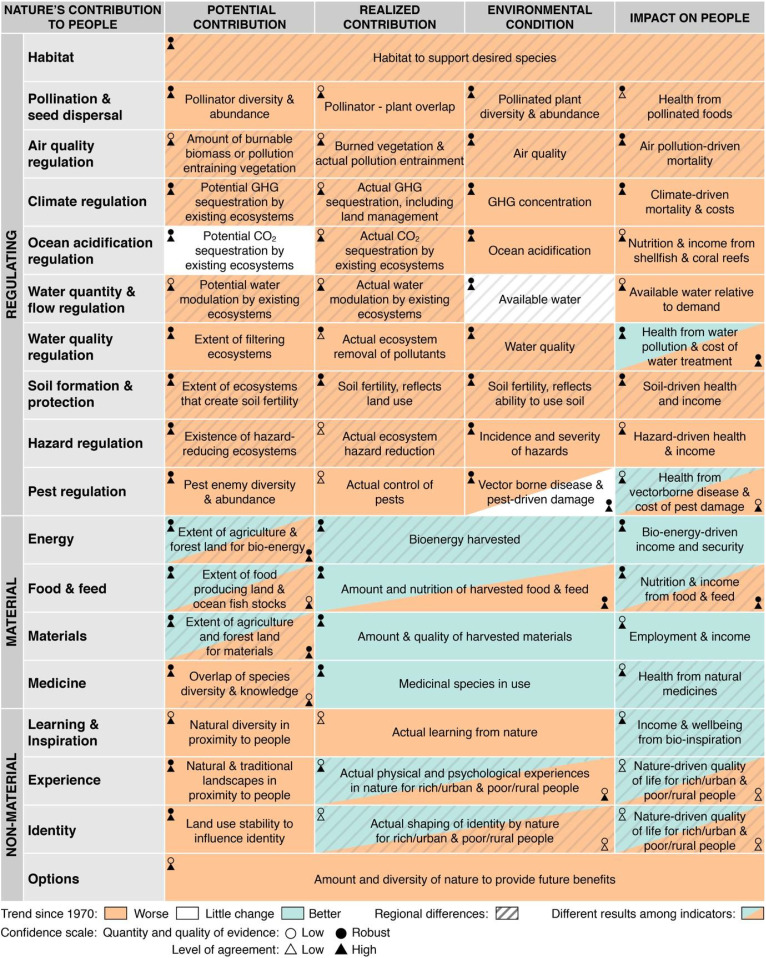

We find that these four related but distinct aspects of nature’s contributions do not have the same trends over time (Fig. 2). Potential contributions unambiguously declined in the majority of categories, reflecting the declines in nature itself over the past 50 y. Although realized contributions and impact on quality of life also declined for many categories, these declines are partly offset by changes in technology and in economic and social conditions. Half of the categories of contribution had unambiguous declines for impact on quality of life. We describe these trends in greater depth below.

Global and regional trends in potential and realized contributions of nature, environmental conditions, and impact on quality of life. Colors indicate global trends since 1970 in potential and realized contributions of nature, environmental condition, and impact on people. Trends summarize a synthesis of over 2,000 articles reviewed for ref. 8. Further explanation of each indicator and references to underlying data are in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Potential and Realized Contributions of Nature, Environmental Condition, and Impact on Quality of Life

Here, we describe in greater detail four distinct but related concepts: 1) potential contributions of nature, 2) realized contributions of nature, 3) environmental conditions, and 4) impact on quality of life (Fig. 1).

Potential Contributions.

Potential contributions describe how nature could impact people and their quality of life, regardless of whether or not those contributions are actually received. Potential contributions are distinct from ecosystem functions or attributes because they are articulated and measured in relation to impacts on people (12). In this assessment, we measure potential contributions based on current biodiversity and ecosystem extent. An alternate approach would be to consider potential contributions that could be available if an ecosystem changed (e.g., how much carbon could be stored if current cropland were converted to forest) or what might have been available at some time in the past (e.g., carbon storage given forest extent before European contact in the Americas). Under this alternate approach, however, potential contributions would remain unchanged with deforestation or other ecosystem conversion. It would also allow simultaneous accounting of potential contributions from conflicting land uses, for example, counting both potential carbon storage in forest and potential crop production from agriculture on the same parcel of land.

Realized Contributions.

In contrast to potential, realized contributions from nature are actually received by people. Realized contributions take into account potential ecosystem contribution along with the proximity, access, anthropogenic assets, and human labor necessary to turn potential into actual contributions to quality of life. To clarify the difference between potential and realized contributions, consider food provision from a marine ecosystem. Although abundant fish stocks create potential, boats and fishing equipment, human labor, and institutions allowing access to fishing grounds must all be employed and fish actually harvested to realize the benefit of nature (Fig. 1) (8).

Environmental Conditions.

We differentiate realized contributions from environmental conditions for regulating contributions of nature. Environmental conditions, such as air or water quality, are generally the outcome people care about and are more frequently measured than the regulation processes encompassed in the potential and realized contribution of nature. Environmental conditions are affected by the contributions of nature, but they are also affected by many other drivers, most notably by pollution, and they differ from realized contributions because, for example, when pollution loads increase, air or water quality may decline even as ecosystem filtration, the realized contribution of nature, increases (16).

Impacts on Quality of Life.

Impacts on quality of life translate realized contributions of nature into benefits to people (or costs in the case of negative impacts). Impacts on quality of life, which can be quantified in monetary or nonmonetary terms using a variety of methods from environmental, social, and psychological sciences as well as biocultural methods (17, 18). Multiple methods are needed to measure health, happiness, learning, and experience, which can vary across cultures. We specifically focus on nature’s impact on quality of life, not on quality of life in general. Changes in realized contributions of nature may not translate directly into impacts on quality of life because of behavioral adaptations or the presence of engineered substitutes. For example, the use of mineral fertilizers has reduced the short-term effects of soil degradation in some places and allowed continued cultivation of crops on low-quality soils (19).

Global Trends in Nature’s Contributions Since 1970

Since 1970, global trends in nature’s contributions to people have declined for a majority of categories (Fig. 2). We report global trends in nature’s contributions to people in three categories: Worse, Little Change, and Better. For each, the net global impact is reported based on available global studies and supported by the findings of the review papers assessed as part of the IPBES Global Assessment that reviewed and synthesized over 2,000 articles from scientific journals, along with reports and other authoritative sources (8, 10). In many cases, trends differ regionally (indicated by hash marks Fig. 2). Potential and realized contributions of nature, environmental condition, and impact on quality of life have different trends (columns in Fig. 2), even within any particular contribution of nature (rows in Fig. 2). We do not provide results across the types of contribution for habitat creation and maintenance of options; their influence on quality of life is felt through their role supporting other contributions of nature. As habitat and biodiversity decline, both habitat creation and maintenance of options also decline (20). Further explanation of each indicator and references to underlying data are included in SI Appendix, Table S1.

Potential Contributions of Nature.

Trends in potential for regulating contributions of nature are driven by biodiversity and habitat intactness. Because these have declined since 1970, potential contributions have declined for virtually all regulating contributions, with the strongest signals for pollination and seed dispersal and for pest regulation (21, 22). Regulation of ocean acidification, which has remained stable over the past 50 y, is the one exception. Regulation of ocean acidification, as distinct from ocean acidification itself, describes the capacity of terrestrial and marine ecosystems to absorb CO2. The warming of the upper ocean has increased ocean net primary productivity somewhat (23), offsetting declines in absorption of CO2 by terrestrial vegetation stemming from deforestation and other ecosystem changes (24).

In contrast, some aspects of potential material contributions have increased. The global extent of land dedicated to bioenergy, food and feed, and materials has increased over the past 50 y (25, 26). However, indicators of potential material contributions that account for stocks of natural resources, such as timber stands and fish populations, have declined (27, 28). In addition, material contributions that depend on biodiversity and/or on indigenous and local knowledge are declining. For example, medicinal products that are wild-harvested are in decline, sometimes as a result of unsustainable overharvesting (29), and populations of wild crop relatives and the diversity of local varieties of plant or animal species are also decreasing (30). Increases in potential material contributions have led directly to declines in other types of contributions of nature. For example, conversion of forests, grasslands, and other habitats for agriculture has decreased the potential of those landscapes to provide contributions such as climate regulation (31).

Potential nonmaterial contributions of nature, which generally require the existence of specific types of land and seascapes in conjunction with people who can connect to them, have also declined. For example, an important element of attachment to nature, which is embedded in culture and identity, is dependent upon a relatively stable environment in which human society is rooted (32). Increased globalization, urbanization, and land degradation have reduced stability of land use and land cover and therefore the attachment of people over multiple generations to their local environment (33). Declines in biodiversity (20) reduce opportunities for learning from nature. Similarly, the decline in population living in direct proximity to nature has reduced human–nature interactions (34).

Realized Contributions of Nature.

For regulating contributions of nature, declines in realized contributions mirror the declines in potential contributions. Declines in natural habitat within agricultural landscapes have led to declining pollination (21), and anthropogenic land management, as distinct from land use change and wholesale deforestation, has decreased the amount of carbon stored in natural landscapes (35). Simultaneously, increases in anthropogenic drivers like pollution have increased regulating contributions of nature through increased assimilation of pollutants. This effect, however, has generally been outweighed by the declining capacity of ecosystems to perform regulating functions (16).

Realized material contributions of nature, which include the amount, quality, and diversity of bioenergy, food and feed, materials, and medicine produced, have increased dramatically over the past 50 y. For example, medicines based on natural compounds or mimicking nature have increased, although this increase has not been as dramatic as the increase in production of commodity crops (26, 36). Material contributions are the most commonly measured realized contributions of nature, as most enter into economic accounts and globally reported statistics. However, increases in realized material contributions have also led to declines in other contributions of nature. Expanding area dedicated to agriculture as well as the extensive use of a narrow range of crop species and varieties, fertilizers, irrigation water, and other farm inputs to enable increased agricultural yields have frequently had negative environmental impacts that reduce other contributions of nature (26).

Trends in realized nonmaterial contributions of nature diverge among groups. For example, for many rural residents and indigenous peoples and local communities, immersion in nature, particularly on a daily basis, has declined with urbanization and the displacement of indigenous and local people from their traditional homes (34). However, realized nonmaterial benefits of nature have increased for some groups, specifically wealthy, mostly urbanized populations who have an increasing interest in nature and the means to visit it or to consume commodities originating at great distance (37).

Environmental Conditions.

For the most part, global trends in environmental conditions have declined since 1970, due largely to increased anthropogenic drivers of environmental decline. For example, greenhouse-gas concentrations, ocean acidification, and soil fertility have worsened with increases in greenhouse-gas emissions and land uses that degrade soil (38). There are some exceptions to declining environmental quality. For example, air quality, as measured by concentrations of particulate matter ≤2.5 μm, has generally improved in high-income countries, where concerted efforts have reduced air-pollution emissions (39). However, since 1970, air quality has declined, often significantly, in many low- and middle-income countries due to increasing emissions (39). Without the regulating contributions of nature, however, the decline in many environmental conditions would likely have been larger.

Impact on Quality of Life.

The impacts of regulating contributions of nature on quality of life mostly trend negative, reflecting declining environmental conditions. For example, air pollution-related morbidity and mortality have increased in low- and middle-income countries, where air quality has declined (39). Exposure to natural hazards has increased, reflecting increases in the severity of storms, fires, and floods as well as increases in the number of people living in high-risk areas (40). Increases in anthropogenic assets and human-made substitutes have moderated or offset declines for some categories of nature’s contributions. For example, improved public health and sanitation measures have reduced the incidence of waterborne disease even as potential and realized water filtration has decreased, although sanitation measures are often costly (31, 41).

For material contributions of nature, increased production of bioenergy, food and feed, materials, and medicines has led to largely positive trends in impact on quality of life. Since 1970, the material standard of living has increased for much of humanity, and the share of people living in extreme poverty has fallen dramatically (42). However, these gains are distributed unequally among both regions and social groups. Despite adequate global caloric production of food, over 800 million people suffer from hunger and malnutrition (25). In addition, indicators of quality of life that are more closely related to the quality and diversity of realized contributions of nature are more likely to be negative. For example, more than 50% of the world’s population depends primarily on natural medicinal products and has little or no access to conventional medicine; they are likely to be negatively impacted by declines in potential and realized natural medicinal products (43).

For nonmaterial contributions of nature, impacts on quality of life show a sharp division between people who are able to capture the benefits of nature and those who are not. For example, for some wealthy urban residents, interest and ability to travel to nature has increased (37), but rural–urban migration and land-use change have decreased exposure to nature, particularly for the poor (44). Similarly, the value of products inspired by nature has increased overall, but that value is concentrated within a small number of industries and companies (45).

Discussion and Future Research

Declines in biodiversity and intact habitat over the past 50 y have resulted in declines in the potential and realized regulating contributions of nature to people. However, there has been an increase in some potential and realized material contributions, particularly from increased yields and the expansion of land devoted to the production of energy, food and feed, and materials. However, increases in intensity and area in production are responsible for declines in other contributions, sometimes including material contributions themselves, reflecting unsustainable use. For nonmaterial contributions of nature, there are divergent trends among social groups.

There is surprisingly little empirical research quantifying the impact of nature on quality of life. Many factors beyond nature’s contributions influence quality of life, and it is often difficult to disentangle the contribution of nature to quality of life from these other factors. While great progress has been made since the publication of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment in 2005, quantifying the impact of nature’s contributions on quality of life requires going beyond natural science information about the status and trends of earth systems to include integrated natural and social science information about how society interacts and coevolves with nature. We also found a lack of research about the distribution of benefits. For most contributions of nature, some prior work has found diverging local trends across regions and social groups, reflecting divergent environmental trends as well as divergent social and economic trends. Effective policy and management advice almost always requires information about the distribution of impacts at regional and local scales and among different groups in society.

Many categories of nature’s contributions include multiple specific contributions, and these do not necessarily exhibit the same trends over time or in different regions. For example, the provision of food and feed includes grain production (maize, wheat, rice), meat, and dairy, which have expanded greatly, as well as wild fisheries, for which many stocks and harvests have declined. Even when a particular contribution of nature is well defined, the choice of indicator representing it may vary substantially, leading to different conclusions (46). Different classifications of nature’s contributions exist, each with varying levels of specificity and thus different grouping and assessments of benefits. In addition, as conditions change through time, what people consider to be normal or “good” may change (shifting baselines), such as when people who have only experienced a depleted fishery think of this as normal (47).

The framework presented here can help guide systematic data collection critically relevant to close these knowledge gaps. Indeed, disentangling potential and realized contributions of nature from one another, from environmental conditions, and from impact on quality of life, at local and regional scales and on different groups within society, is vital for designing and implementing appropriate management and adaptation measures to reverse declining trends in nature’s contribution to quality of life. Integrating the work reported on here with ongoing efforts, such as the System of Environmental Economic Accounts (48, 49), is a promising direction for improving society’s ability to manage earth systems effectively, equitably, and sustainably. Information alone, however, is not sufficient for reversing declines. Information is a useful input that can help catalyze changes in attitudes and behavior, along with reform of institutions and policies, which are necessary elements for reserving declines in biodiversity and ecosystems essential for the continued flow of contributions to quality of life.

Methods

As part of the IPBES global assessment, we systematically reviewed trends in 18 contributions of nature to people. To evaluate each type of contribution of nature in a consistent manner, we developed a set of assessment questions. These questions address how nature and people coproduce the contribution, approaches for measuring the production of the contribution, links with other contributions, indicators used to represent the provision of these contributions, information about global trends in provision, and, where available, trends within different biomes and land-use types, as defined by IPBES. We also assessed how the impact on human wellbeing for a contribution of nature is defined, how the value of the contribution is measured, indicators of the impact of the contribution on quality of life, whether substitutes for the contribution are available, global trends on the impact on quality of life, and trends by user group.

To populate these categories of information for each type of contribution, we searched the peer-reviewed and gray literature (10), largely using Google Scholar. We focused on publications that reviewed multiple empirical studies and surveys of literature. Although we started with literature that self-identifies as relevant to ecosystem services or nature’s contributions to people, this literature does not address the breadth of information we sought to collect, so we used a snowball approach in conjunction with expert knowledge to amass additional evidence. Detailed information for each type of nature’s contribution to people are available as an appendix to the IPBES Global Assessment, Chapter 2.3: Status and Trends–Nature’s Contributions to People (50).

We selected representative indicators for each type of contribution. Candidate indicators were identified through review of the literature. Selection criteria prioritized scientific soundness, availability of information, IPBES policy relevance, and alignment with indicators used in prior assessments. We selected separate indicators for potential contributions, realized contributions, environmental outcomes, and impact on quality of life for each contribution. Once an indicator for a particular outcome for a particular contribution was agreed on by the expert group, several key papers with evidence supporting the overall trend found in the larger review were gathered and cited in the evidence table. More in-depth descriptions of each indicator and references supporting our conclusions are contained in SI Appendix, Table S1.

We assessed the weight of evidence on trends for each of these indicators (reported in Fig. 2). Evidence was evaluated using the IPBES four-box model for the qualitative communication of evidence, which considers the quantity and quality of evidence (low to high) and the level of agreement among that evidence (low to high).

There are many distinct ways that nature contributes to quality of life, even within the relatively narrow types of contributions defined by IPBES. For example, materials used by people range from building materials to textiles, ornamental plants, and animals that serve as human companions. To synthesize this diverse information, we deliberated as a group, coming to consensus on indicators that were acceptably representative of major aspects of each category of contribution for each element of that contribution. In some cases, elements of a category of nature’s contribution are so disparate, with diverging trends, that we report on multiple indicators.

Our choice of indicators reflects our judgement of the best available metrics of nature’s contributions at present, and this could be used as the starting point for future programs of systematic data collection. Continued improvement in metrics and choices of appropriate indicators will be an ongoing process.

Acknowledgements

We thank Vanessa Sontag for assistance with figures. This work would not have been possible without the leadership of IPBES Global Assessment Co-Chairs Sandra Díaz, Joesf Settele, and Eduardo Brondízio; IPBES Chair Sir Robert Watson; and IPBES Executive Secretary Anne Larigauderie. We particularly thank Hien T. Ngo and Maximilien Guèze at the IPBES Technical Support Unit for their unwavering support. We thank the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment for support to K.A.B., the Fesler-Lampert Professorship for support to S.P., and the South African Research Chair in Marine Ecology and Fisheries for support to L.J.S.

Data Availability.

All study data are included in the article and SI Appendix.

Change History

December 24, 2020: The license for this article has been updated.

References

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

Global trends in nature’s contributions to people

Global trends in nature’s contributions to people