- Altmetric

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Apolipoprotein E in physiology and disease

- 3 A new association of APOE with COVID-19 clinical outcomes

- 4 Mechanisms that may underpin the association of APOE with the clinical outcomes of COVID-19

- 5 Putative pharmacological and dietary approaches for the prevention and management of COVID-19 in APOE ε4/ε4 individuals

- 6 Discussion

- Author contributions

- Funding

- Declaration of competing interest

COVID-19 incidence and case fatality rates (CFR) differ among ethnicities, stimulating efforts to pinpoint genetic factors that could explain these phenomena. In this regard, the multiallelic apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene has recently been interrogated in the UK biobank cohort, demonstrating associations of the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype with COVID-19 severity and mortality. The frequency of the ε4 allele and thus the distribution of APOE ε4/ε4 genotype may differ among populations. We have assessed APOE genotypes in 1638 Greek individuals, based on haplotypes derived from SNP rs7412 and rs429358 and found reduced frequency of ε4/ε4 compared to the British cohort. Herein we discuss this finding in relation to CFR and hypothesize on the potential mechanisms linking APOE ε4/ε4 to severe COVID-19. We postulate that the metabolic deregulation ensued by APOE4, manifested by elevated cholesterol and oxidized lipoprotein levels, may be central to heightened pneumocyte susceptibility to infection and to exaggerated lung inflammation associated with the ε4/ε4 genotype. We also discuss putative dietary and pharmacological approaches for the prevention and management of COVID-19 in APOE ε4/ε4 individuals.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a respiratory infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Infection is mediated by the proteolytic priming of the viral spike (S) envelope glycoprotein by the cellular transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor expressed at the plasma membrane of several cell types, including pneumocytes, intestinal epithelial cells, macrophages and endothelial cells [1].

Severe COVID-19 is associated with damage of the alveolar capillaries interfering with the gas exchange function and leading to the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is characterized by bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, severe hypoxemia and an aberrant immune response that may culminate to septic shock, multi-organ dysfunction and death. The immunological mechanisms involved in severe COVID-19 are not fully elucidated but it has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 infection may not trigger the conventional route of antiviral immunity: instead of activating first the antiviral response followed by pro-inflammatory processes as a second line of defense, it triggers the pro-inflammatory response long before interferon-mediated antiviral defenses are induced - if at all [2]. Inflammation is likely to be initiated by infected pneumocytes as a result of NLRP3-dependent inflammasome activation and intracellular Toll-like receptor signaling by viral proteins and RNA. This, in turn, induces pneumocyte pyroptosis and release of cytokines and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as HMGB1 and ATP [3] as a result of lytic cell death [4]. DAMPs are recognized by neighboring epithelial cells, endothelial cells and alveolar macrophages, triggering NLRP3-dependent inflammasome activation and other signaling pathways that culminate to the production and secretion of several pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines [4]. These molecules attract neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages and T cells to the site of infection, amplifying inflammation and lung tissue damage. The resulting “cytokine storm” ensues systemic effects, aggravating disease symptoms and occasionally leading to multi-organ failure.

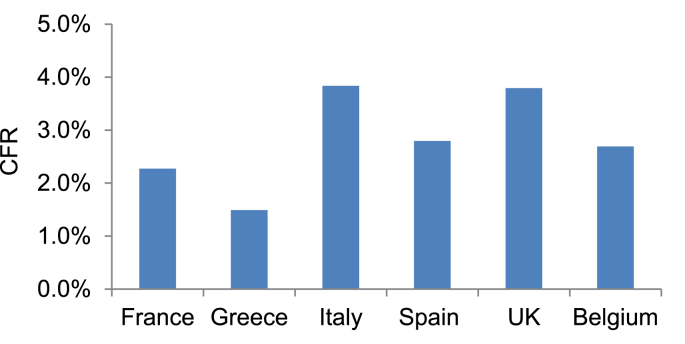

The clinical outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection are influenced by several factors, related to both the host and the virus. Older age, obesity, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), as well as viral load kinetics are risk factors for the development of severe disease and mortality [1]. These risk factors, however, do not fully explain why some people have mild or no symptoms whereas others develop severe responses. In addition, the case fatality rate (CFR) of COVID-19 differs among ethnicities (Fig. 1). These differences have sparked considerable interest in defining genetic factors impacting clinical outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Herein we discuss recently published evidence implicating the multiallelic Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene in COVID-19 severity and mortality [5,6].

Case fatality rates (CFR) of COVID-19, defined as the number of confirmed deaths divided by the number of confirmed cases, in various European countries till November 15, 2020. Data were extracted from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) web site, https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en.

Apolipoprotein E in physiology and disease

APOE is a member of the apolipoprotein family that controls organismal lipid and cholesterol homeostasis [7]. APOE participates in cellular cholesterol efflux from hepatic and non-hepatic tissues, cholesterol transport, and clearance of lipoprotein remnants in the plasma [8]. The protein is mainly associated with triglyceride-rich Very Low Density Lipoprotein (VLDL) particles to mediate extra-hepatic lipid supply and, secondarily, with High Density Lipoprotein (HDL) particles for reverse cholesterol transport (RCT), a process that transfers excess cholesterol from non-hepatic tissues back to the liver for excretion. Delivery of lipids to cells by VLDL is mediated via binding of APOE to membrane Low Density Lipoprotein Receptors (LDLR) followed by receptor-mediated lipoprotein endocytosis. Cholesterol efflux entails the transfer of cholesterol to the lipoprotein via ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1.

Most of APOE in the plasma is derived from hepatocytes, but 20–40% of total APOE is produced in non-hepatic tissues, including macrophages, adipocytes, glial cells, neurons and some epithelial cell types. Expression patterns are of interest as they may point to potential physiological functions and/or tissue-specific pathological manifestations of APOE deregulation. For example, APOE is detected in several cell types in the lung, including alveolar macrophages, type I and type II alveolar epithelial cells and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells [9]; studies in the mouse have shown that ablation of apoe results in defects in lung development typified by impaired alveologenesis, increased airway resistance and accelerated loss of lung recoil during aging [10]. Likewise, hepatic ablation of apoe leads to accelerated liver aging [11] and steatohepatitis when mice are fed a high cholesterol diet [12]. APOE also contributes to cholesterol efflux from lipid-laden macrophages (foam cells) reducing formation of lesions in the arterial wall [13,14]. Beyond these important biological functions that directly relate to lipid metabolism, APOE mediates anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory effects [15,16], in common with other apolipoproteins [17].

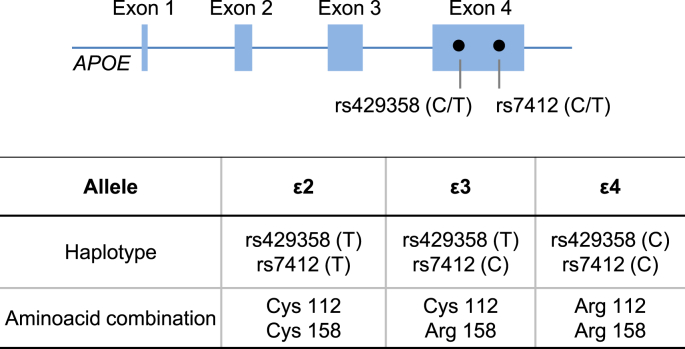

Although these knock-out studies in the mouse are informative, they do not fully reflect the complexity of the effects of human APOE. This is because unlike rodents, the APOE gene is polymorphic in humans. The most prominent variants are single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) rs429358 [C/T] and rs7412 [C/T], both in exon 4 of the gene, which is located on chromosome 19q13.2 (Fig. 2). Three haplotypes emerge, ε2, ε3 and ε4 translating to three protein isoforms, E2, E3 and E4, and six combinations of variants, ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε2/ε4, ε3/ε3, ε3/ε4 and ε4/ε4 can be found [18,19]. Among them, ε4/ε4 has attracted most attention because of indisputable epidemiological and experimental evidence that links it to several human pathologies [7].

Schematic representation of the human APOE gene and positions of SNPs rs7412 and rs429358 in exon 4 of APOE. Depending on the SNP combinations, 3 haplotypes arise for each allele termed ε2, ε3, ε4, resulting in different amino acid combinations at residues 112 and 158.

Indeed, the APOE ε4 variant is a genetic risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and E4 expression is associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness and higher total blood and LDL-bound cholesterol [20]. In fact, variation at the APOE locus accounts for ≈7% of the population variance in total and LDL-cholesterol concentrations [21]. The ε4/ε4 genotype is also linked to both sporadic and familial late onset Alzheimer's disease (AD), reportedly increasing disease risk by up to tenfold, compared to ε3/ε3, whereas ε2/ε2 is associated with reduced risk [22]. A recent phenome-wide association study of APOE genotypes with 950 disease outcomes registered in the UK biobank confirmed the elevated risk of cardiovascular diseases, AD and hypercholesterolaemia associated with ε4 (ε3/ε4 or ε4/ε4) compared to the ε3/ε3 genotype [23].

APOE is also linked to cellular and organismal responses to infection by viruses and pathogenic microorganisms. Notably, the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype is associated with increased susceptibility to HIV-1 infection and aggravated disease course of AIDS [24], and to susceptibility for HSV-1 related herpes labialis and neuronal invasiveness of HSV-1 compared to other APOE variants [25].

A new association of APOE with COVID-19 clinical outcomes

Two recent studies have added COVID-19 to the panel of pathologies associated with the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype [5,6]. Kuo et al. analyzed genetic and clinical data registered in the UK Biobank (>450,000 European-ancestry participants) and uncovered a 2-fold higher risk of severe COVID-19 of people carrying the ε4/ε4 versus the ε3/ε3 genotype [6] and a 4-fold increase in mortality after testing positive for COVID-19 [5]. These associations were independent of preexisting dementia, cardiovascular disease and type-2 diabetes.

Given previous evidence suggesting that the frequency of ε4/ε4 carriers may vary among populations [26], the findings by Kuo et al. could, potentially, also explain some of the reported differences in SARS-CoV-2 disease outcomes in different ethnicities. The lower CFR in Greece compared to the UK which is rated among the European countries with the highest COVID-19 mortality (Fig. 1), prompted us to compare the frequencies of APOE ε4/ε4 genotype in Greeks versus British. We assessed APOE genotypes in 1638 Greek individuals, based on haplotypes derived from SNPs rs7412 and rs429358 and compared the results with the APOE genotyping data extracted from the UK biobank, as reported elsewhere [23]. The distribution of APOE genotypes was found to significantly differ between the two populations (Table 1). Of note, ε4/ε4 is found in 2.42% of European ancestry British but only in 1% of the Greek population cohort with the frequency of the ε4 allele being 0.1563 and 0.0919, respectively (Table 2). Our data is in agreement with and largely extend a previously reported ε4 frequency of 0.1020 in a cohort of 240 healthy middle-age Greeks based on a PCR-RFLP method [27]. These observations warrant further studies to confirm the findings of the UK Biobank [5,6] in other populations. Further investigations are also needed to dissect the biological mechanisms linking APOE genotypes to COVID-19 severity.

| APOE Genotype | COUNT | % distribution | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRITISH | GREEK | BRITISH | GREEK | |

| ε4ε4 | 8179 | 20 | 2,42% | 1,00% |

| ε3ε4 | 80499 | 242 | 23,85% | 15,00% |

| ε2ε4 | 8616 | 19 | 2,55% | 1,00% |

| ε3ε3 | 196306 | 1203 | 58,17% | 73,00% |

| ε2ε3 | 41695 | 142 | 12,36% | 9,00% |

| ε2ε2 | 2172 | 12 | 0,64% | 1,00% |

| Total | 337467 | 1638 | 100% | 100% |

Mechanisms that may underpin the association of APOE with the clinical outcomes of COVID-19

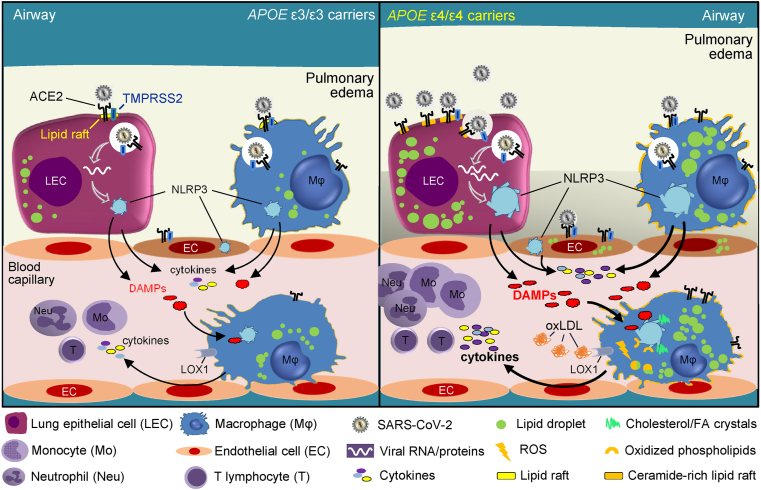

Scrutinizing some of the known molecular roles of different APOE isoforms provides putative mechanistic clues into the association of APOE ε4/ε4 with COVID-19 severity. Cholesterol may be central to it (Fig. 3).

Graphical representation of the main mechanisms by which APOE E4/E4 may impact COVID-19 severity and mortality. The APOE ε4/ε4 genotype is associated with elevated levels of circulating and tissue cholesterol and oxidized LDL (oxLDL). Their intracellular accumulation in pneumocytes, lung macrophages and endothelial cells increases the density of ACE2/TMPRSS2 in ceramide and cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains (lipid rafts), resulting in heightened susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection (right panel) relative to ε3/ε3 cells (left panel). This, in turn, leads to heightened NLRP3 inflammasome activation, pyroptosis and release of DAMPs. We also postulate that the elevated levels of oxLDL in ε4/ε4 carriers result in basal inflammasome activation in alveolar and recruited monocyte-derived macrophages through LOX-1 – mediated oxLDL internalization, production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the generation of oxidized lipids and cholesterol crystals which serve as endogenous DAMPs. These macrophages are thus subject to inflammasome hyperactivation and to amplified pyroptosis in response to lung infection by SARS-CoV-2, unleashing a “cytokine storm” that ensues recruitment of immune cells, pulmonary edema and severe systemic effects.

APOE4 may influence SARS-COV-2 infectivity by modulating intracellular cholesterol levels

APOE isoforms differentially affect intracellular and circulating cholesterol levels. A meta-analysis of 14,799 individuals from 17 different ethnicities has confirmed that carriers of the ε4 allele have higher levels of plasma cholesterol than individuals with the ε3/ε3 genotype [28], a phenomenon that is mirrored in the APOE4 targeted replacement mouse fed a western type diet [29].

Chronic administration of high-fat diet increases cholesterol levels in mouse lung tissue by 40% [30] which is exaggerated in the absence of apoe [31] and most likely reflects changes in the circulating levels of cholesterol. Indeed, lipid tracing experiments in rodents have shown that approximately 83% of lung cholesterol is derived from the plasma with the remainder coming from synthesis by lung-resident cells [32]. It is thus likely that beyond elevated cholesterol levels in the plasma, the ε4 allele may also be associated with excess cholesterol in pneumocytes.

What could be the consequences of elevated intracellular cholesterol levels for COVID-19? Several observational studies have shown that the severity of COVID-19 is associated with reduced serum HDL which indicates defects in the reverse cholesterol transport (RCT) pathway responsible for lipid homeostasis in peripheral tissues [33,34]. Along these lines, abnormal pulmonary accumulation of lipid-laden macrophages has been noted in COVID-19 [35]. Intracellular cholesterol also accumulates with age in several tissues [36,37], including pneumocytes [38], which correlates with increased COVID-19 severity in older people.

Beyond these correlations, a recent pre-print report directly links high cellular cholesterol to increased SARS-CoV-2 infectivity [30]. Loading cells with cholesterol increases ACE2 trafficking to the endocytic entry site and doubles the endocytic entry points of the virus [30]. Cholesterol may also impact the production of more infectious virions with improved binding to the ACE2 receptor [30]. The spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 contains the sequence PRRAR which is cleaved by furin proteases that are abundant in the respiratory tract. Cholesterol optimally positions the S glycoprotein furin cleavage site for proteolysis upon exit from epithelial cells and consequently the virus may infect other cells with increased efficiency [30]. It has also been reported that compared with ε3/ε3 subjects, monocytes from APOE ε3/ε4 individuals display an increase in cholesterol-enriched membrane microdomains (lipid rafts) [39] which represent sites for initial binding, internalization and cell-to-cell transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [40]. Therefore, APOE4 may influence SARS-CoV-2 infectivity by affecting intracellular cholesterol levels.

APOE4 may enhance SARS-CoV-2 induced inflammation by priming the NLRP3 inflammasome

In humans, APOE4 has been associated with a heightened innate immune response to bacteremia [41], including higher production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF by activated macrophages [42], prothrombotic properties of endothelial cells [43], as well as neuroinflammation characterized by increased expression of CCL3 in the brain [44]. Although a detailed characterization of the cytokines and chemokines affected by APOE4 in different pathological conditions and tissues is still missing, IL-6, TNF and CCL3 represent some of the cytokine storm markers of severe COVID-19 [4,39]. Moreover, whilst the mechanisms underlying these APOE4 effects are not entirely understood, we hypothesize that deregulated lipid metabolic processes may bridge APOE4 with heightened pro-inflammatory responses to SARS-CoV-2.

The exaggerated inflammation observed in severe COVID-19 has largely been attributed to over-activation of NLRP3 inflammasome that leads to overproduction of IL-1β, a clinical target for COVID-19. Currently, cholesterol and fatty acids are emerging as important regulators of NLRP3 signaling through various routes [45,46]. It has been shown that saturated fatty acids palmitic and stearic undergo intracellular crystallization in lipid-laden macrophages and activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro and in vivo by serving as endogenous DAMPs [47]. Cholesterol crystals, detected in the lungs of heavy smokers [48], idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [49] and lipoid pneumonia [50], are also potent inducers of NLRP3 [51]. It could thus be envisaged that by exaggerating cholesterol accumulation in the lung [30], APOE4 may prime epithelial cells, macrophages and endothelial cells towards heightened inflammasome activation in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection (Fig. 3). This concept is compatible with the higher basal activity of NLRP3 in mouse models and patients with obesity [52,53] that constitutes a risk factor for severe COVID-19. Likewise, inflammasome activation parallels the low-grade inflammation associated with ageing [54], which also constitutes a risk factor for severe COVID-19 [1,54]. In addition to functioning as intracellular DAMPs, cholesterol crystals trigger neutrophils to release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) which are found in cholesterol-rich atherosclerotic plaques in apoe−/- mice and prime macrophages to release cytokines [55]. Notably, elevated serum markers of NETosis are observed in severe cases of COVID-19 [56].

Cholesterol also impacts T cell receptor (TcR) signaling through membrane raft formation that enables TcR signal initiation, higher sensitivity to TcR ligands and T cell proliferation [57]. Intracellular sterols also promote T cell differentiation towards Th17 [58]. This differentiation may explain the increased numbers of Th17 cells in high cholesterol-fed atherosclerotic apoe−/- mice [59]. Interestingly, humans expressing the APOE4 isoform (ε3/4, ε4/4) have increased circulating numbers of activated T cells [60] and patients affected by COVID-19 pneumonia display marked T cell activation and skewing toward the Th17 phenotype [61]. Based on these observations we speculate that the metabolic deregulation ensued by APOE4 may prime pneumocytes, macrophages and endothelial cells towards heightened inflammasome activation and cytokine production and amplify tissue and systemic effects of SARS-CoV-2 on T cell numbers and differentiation (Fig. 3).

APOE4 may enhance the pathogenic effects of SARS-CoV-2 through LDL lipid oxidation

LDL oxidation is caused by enzymatic or non-enzymatic oxidative modifications of LDL lipids and apolipoproteins [62]. Lipid oxidation is driven by excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are generated as a result of vascular oxidative stress in hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking and other pathologies [63]. The end product of lipid oxidation is the formation of oxidized LDL (oxLDL) that contains several hundred bioactive phospholipid, triglyceride and cholesterol products [62].

OxLDL is a key pathogenic factor in the development of atherosclerosis, because it is recognized and taken up by scavenger receptors expressed in macrophages leading to the formation of foam cells that are found in atherosclerotic lesions [63]. OxLDL also exerts pro-inflammatory properties by binding to lectin-like oxidized low-density lipoprotein receptor-1 (LOX-1) and the heterotrimer of CD36/TLR4/TLR6 expressed on monocytes/macrophages and endothelial cells. The binding of oxLDL to LOX-1 results in its internalization, causing intracellular lipid accumulation and the activation of several pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative pathways [62]. For example, oxLDL has been shown to stimulate the production of ROS and of pro-inflammatory lipids, including isoprostanes generated through free radical-induced peroxidation of arachidonic acid [64]. Oxidized phospholipids (oxPLs) are a major component of oxLDL and serve as DAMPs that activate NLRP3, leading to the secretion of IL-1β/IL-18 [65]. The relevance of LDL oxidation to lung diseases is highlighted by the observation that intranasal administration of human oxLDL to mice initiates an inflammatory response that mirrors the characteristics of cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation [60].

Several lines of evidence indicate a possible link between oxLDL and COVID-19. First, beyond atherosclerosis, elevated levels of circulating oxLDL are detected in obesity, metabolic syndrome and COPD [[66], [67], [68], [69]], all of which are risk factors for severe COVID-19 [1]. Second, the pro-inflammatory pathways triggered by oxLDL have common elements with those activated by SARS-CoV-2, and involve DAMP-orchestrated inflammation. Third, oxLDL increases the expression levels of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 [70] and the density of cholesterol and ceramide-enriched lipid rafts [71] that contribute to enhanced virus infectivity [40,72]. Finally, oxPLs are detected in the inflammatory exudates overlaying pneumocytes and macrophages in the injured air spaces of patients infected with SARS-CoV [73]. Based on these observations, we hypothesize that oxLDL may increase host cell susceptibility to the pathogenic effects of SARS-CoV-2.

APOE confers protection against oxidative stress in the lung. Ablation of apoe in the mouse exacerbates acute lung injury, causing an ARDS-like condition due to elevated oxLDL and IL-6 levels [74]. APOE4 has the least effective antioxidant properties compared with other APOE isoforms [75] and is less effective in inhibiting LDL oxidation in vitro [76,77]. APOE4 is also positively associated with markers of oxidative stress. Thus, APOE ε4/ε3 individuals have elevated levels of lipid peroxides [78], and smokers who are carriers of the ε4 allele have a 26.7% increase in the serum levels of oxLDL compared to other APOE genotypes [79]. Collectively, these findings suggest that APOE4 is linked to elevated levels of oxLDL, particularly under conditions of chronic or acute inflammation, which may amplify susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the lung.

Putative pharmacological and dietary approaches for the prevention and management of COVID-19 in APOE ε4/ε4 individuals

We have herein reasoned that elevated cholesterol and oxidized lipoproteins may serve as important mediators of the detrimental effects of APOE ε4/ε4 genotype on the severity and mortality of COVID-19. Thus, it might be possible to mitigate the consequences of COVID-19 infection by pharmacological and dietary strategies that reduce cholesterol burden in individuals with the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype.

Statins are cholesterol-lowering drugs targeting HMG CoA reductase, the enzyme controlling the rate-limiting step of cholesterol biosynthesis pathway. Administration of statins, in addition to the reduction in LDL-cholesterol, also reduces circulating oxLDL [80,81]. Statins have demonstrated beneficial effects on several viral-induced pathologies, including a significantly reduced risk of influenza death among moderate-dose statin users [82], improved outcomes of anti-retroviral therapy in HIV-positive patients [83] and reduced mortality of Ebola virus disease patients [84]. Notwithstanding the pleiotropic functions of statins that include systemic immunomodulatory properties, a direct in vitro effect of lovastatin on reducing production of infectious Ebola virus has been reported [85].

The clinical utility of statins for the management of COVID-19 has been debated [86]. However, a recently published meta-analysis of 4 clinical studies involving a total of 8990 COVID-19 patients concluded that statins reduce the hazard for severe or fatal COVID-19 cases [87]. There have been some concerns that treatment with statins may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes, especially in obese patients [88]. Notably, although statin users without the APOE ε4 risk allele have greater insulin resistance, APOE ε4 carriers have improved insulin function [89]. It would thus be of interest to examine if the beneficial effects of statins are more pronounced in ε4/ε4 COVID-19 patients compared to other APOE genotypes. Biological agents such as APOE mimetic peptides and antibodies that neutralize oxPLs present in oxLDL are being evaluated in the context of atherosclerosis [90] and may offer additional opportunities for the management of ε4/ε4 COVID-19 patients.

The APOE4 isoform is considered generally insensitive to dietary interventions. For example, plant sterols reduce blood cholesterol levels in hypercholesterolemic patients with APOE ε3/ε3 genotype but not ε4 carriers [91]. However, specific dietary plans for APOE4 isoform carriers are both feasible and effective [92]. Thus, a 24 week diet that replaces saturated with monounsaturated fats or with low glycaemic index carbohydrates has been found to benefit APOE4 carriers to a greater extent compared to other APOE isoforms in reducing plasma cholesterol [93]. A similar hypotriacylglycerolaemic effect specifically on APOE4 carriers has been reported following a 4 week healthy diet supplemented with daily consumption of two kiwifruit presumably by increasing intake of lipid-lowering anti-oxidant vitamins and polyphenols [94].

Chronic consumption of fish-derived omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and of docosahexaenoic acid in the form of lysophosphatidylcholine have also been reported to benefit APOE ε4 carriers by lowering their blood triglyceride concentrations [92] and possibly promoting resolution of inflammation through the production of proresolving lipid mediators such as resolvins and protectins [95]. The potential benefit of this dietary approach for modulation of lung inflammation is illustrated by experimental data showing that accumulation of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids in the lungs of APOE-deficient mice fed a diet with reduced omega-3 fatty acids is reversed by supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids [96]. Interestingly, dexamethasone which now constitutes standard care for the treatment of severe COVID-19 patients in need of oxygen support or mechanical ventilation [97], has also been shown to induce proresolving lipid mediators such as protectin D1 [98,99]. APOE ε4 carriers may also have a slightly increased demand for vitamin E [91,100], which confers anti-oxidant and immunoregulatory effects that are beneficial to viral respiratory tract infections [101].

Discussion

APOE is a multifaceted protein that has been implicated in several pathologies and displays isoform-dependent effects. Homozygous carriers of the E4 isoform are particularly vulnerable to cardiovascular disease, hypercholesterolaemia, stroke, Alzheimer's disease and virus-induced pathologies. COVID-19 has recently joined the network of APOE ε4-related diseases with a significant association between APOE ε4/ε4 genotype and COVID-19 severity and mortality [5,6]. Recent experimental evidence supports the heightened sensitivity of ε4/ε4 neurons and astrocytes to SARS-CoV-2 infection [102].

The frequency of the ε4 allele and thus the distribution of APOE ε4/ε4 genotype may differ among ethnicities [103]. Data presented herein demonstrate that the frequency of ε4/ε4 genotype in a Greek cohort is significantly lower than in European ancestry UK biobank British cohort, which parallels the lower COVID-19 CFR in Greece as compared to the UK. Notwithstanding the complexity of responses to SARS-CoV-2 that are likely to be influenced by a multitude of host, virus and environmental factors, this observation suggests that putative associations between the genetic make-up of ethnic groups with the incidence, severity and mortality of SARS-CoV-2 infection should be explored, along the lines of a recently published GWAS [104].

Further investigations are also needed for the elucidation of the biological mechanisms linking APOE genotypes to COVID-19 severity. Increased levels of intracellular and systemic cholesterol typify the metabolic function of APOE E4/E4 [28], and may be central to this association (Fig. 3). We propose that the accumulation of cholesterol and oxLDL in pneumocytes ensued by ε4 homozygocity may result in greater susceptibility and severity to SARS-CoV-2 infection. This is likely to be caused by quantitative and qualitative changes in lipid rafts and a high oxidative status in the cells lining the lung airways. Under these conditions, there is increased expression of ACE2 and TMPRSS2 at the plasma membrane that leads to increased virus binding, internalization and cell-to-cell transmission (Fig. 3). Beyond SARS-CoV-2, lipid rafts play a prominent role as the entry points of several viruses [105], including HIV-1 the infectious cycle of which is also influenced by the APOE ε4/ε4 genotype [24].

Compared to other isoforms, APOE4 may promote basal NLRP3 inflammasome activation that exaggerates inflammatory responses in the lung, pertinent to the “cytokine storm” of severe COVID-19 (Fig. 3). The detrimental clinical effects of APOE4 on COVID-19 [5,6] may depend on or be amplified by the co-occurrence of additional factors, such as smoking, obesity, asthma or COPD, as previously recorded for CVD risk [79,106].

In favor of the aforementioned model implicating lipid metabolism at the core of the APOE4 – COVID-19 connection, statins provide clinical benefit to COVID-19 patients. We reason that APOE ε4/ε4 individuals, who are at increased risk of severe COVID-19, could particularly benefit from preventive dietary changes and/or therapeutic use of moderate-doses of statins. The major influence of APOE4 on lipid metabolism, however, does not exclude the possibility that other APOE4 functions in the lung impact the clinical outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection. In this regard, the APOE ε4 allele has been associated with reduced lung respiratory capacity in the elderly irrespective of lipid levels [107], and apoe ablation in the mouse is associated with the development of severe pulmonary hypertension [108], which increases the risk of death in COVID-19 patients.

Since its discovery in 1973 by Havel and Kane [109], APOE continues to surprise us with new associations with several diseases and represents a fertile ground for future research.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, K.G. and A.G.E.; methodology, materials and formal analysis, K.G, T.V., N.D., M.G., D.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.G.E. and D.S.; writing—review and editing, all authors; funding acquisition, D.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

CURE-PLaN, a grant from the Leducq Foundation for Cardiovascular Research.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest with the exception of K. Gkouskou who is founder and CEO of Embiodiagnostics S.A.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

COVID-19 enters the expanding network of apolipoprotein E4-related pathologies

COVID-19 enters the expanding network of apolipoprotein E4-related pathologies