Edited by Susan G. Amara, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, and approved March 9, 2021 (received for review February 20, 2021)

Author contributions: A.K.S., P.B.G., and D.P.O. designed research; A.K.S., P.B.G., I.E.G., J.D., and H.P. performed research; M.G.M. and D.P.O. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; A.K.S. and P.B.G. analyzed data; and A.K.S., P.B.G., and D.P.O. wrote the paper.

1A.K.S. and P.B.G. contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

The ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) is a critical neural node that senses blood glucose and promotes glucose utilization or mobilization during hypoglycemia. The VMH neurons that control these distinct physiologic processes are largely unknown. Here, we show that melanocortin 3 receptor (Mc3R)-expressing VMH neurons (VMHMC3R) sense glucose changes both directly and indirectly via altered excitatory input. We identify presynaptic nodes that potentially regulate VMHMC3R neuronal activity, including inputs from proopiomelanocortin (POMC)-producing neurons in the arcuate nucleus. We find that VMHMC3R neuron activation blunts, and their silencing enhances glucose excursion following a glucose load. Overall, these findings demonstrate that VMHMC3R neurons are a glucose-responsive hypothalamic subpopulation that promotes glucose disposal upon activation; this highlights a potential site for targeting dysregulated glycemia.

The central nervous system contributes to systemic glucose homeostasis. Glucose sensing neurons are found within the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH), a brain structure that plays a prominent role in both the counterregulatory response to hypoglycemia (12–3), and glucose disposal (4). Direct VMH infusion of melanocortin agonists, endogenously produced in the arcuate nucleus (ARC), promotes glucose uptake into skeletal muscle independent of insulin release (5, 6). Furthermore, VMH-specific reexpression of MC3Rs in an MC3R-null background increases glucose utilization without altering energy balance (7), suggesting that VMHMC3R neurons may regulate glucose disposal.

Using genetic tools, we find that VMHMC3R neurons respond directly and indirectly to altered glucose levels. Potential presynaptic regulators of VMHMC3R neurons include melanocortin-producing ARC neurons and other brain regions important for glycemic control. We demonstrate that VMHMC3R neuron activity is both necessary and sufficient for glucose disposal, and that activation of this population has the potential to attenuate diet-induced glucose intolerance.

Results

VMHMC3R Neurons Sense Glucose Changes Both Directly and Indirectly and Receive Input from Glucose-Sensing Regions.

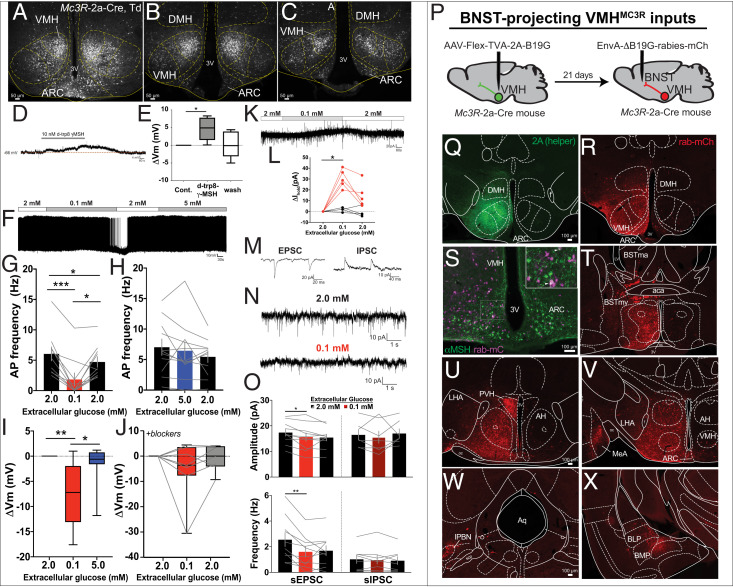

Mc3R-2a-Cre mice (8) were crossed to the Rosa26Ai14tdTomato reporter for electrophysiological analysis of VMHMC3R neurons (Fig. 1 A–C). Application of the MC3R-selective agonist d-trp8-γMSH (10 nM) depolarized VMHMC3R neurons (Fig. 1 D and E) (9). Decreasing glucose from 2 to 0.1 mM suppressed the activity of VMHMC3R neurons; returning glucose to 2 mM depolarized VMHMC3R neurons and restored their firing (Fig. 1 F, G, and I). Increasing glucose to 5 mM did not significantly affect VMHMC3R membrane potential or firing (Fig. 1 F, H, and I). The hyperpolarization of VMHMC3R neurons in low glucose persisted during blockade of action potential (AP) firing and synaptic input in four of seven neurons, indicating direct glucose regulation (Fig. 1J). Likewise, low glucose activated an outward current in five of nine cells (Fig. 1 K and L).

VMHMC3R neurons are regulated by melanocortins and glucose, with inputs from local brain regions. (A–C) VMHMC3R neurons visualized in Mc3R-2a-Cre, Td mice. Current-clamp recordings show depolarization of VMHMC3R neurons by d-trp8-γMSH with synaptic blockade (D and E; 4/5 neurons), decreased AP firing (F and G; 10/10 neurons), and hyperpolarization in low glucose (F and I; 11/13 neurons). Approximately 50% (4/7) of VMHMC3R neurons directly respond to low glucose with synaptic blockers present (J), likely due to a net outward current (K and L). Indirect regulation of VMHMC3R neurons in low glucose was measured by simultaneously recording EPSC and IPSCs (M). Low glucose decreased amplitude and frequency of sEPSCs, but not sIPSCs (N and O). Identification of presynaptic inputs to VMHMC3R neurons projecting to the BNST using modified rabies virus tracing (P–R) identifies ARC inputs (S, purple) containing αMSH (S, green). Additional inputs include the PVH (U), MeA (V), lPBN (W), and BMP (X). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (G, H, and O), or box plots ± maximum/minimum (E, I, and J). Significance was determined using a repeated-measures one-way ANOVA (E, G, H, J, K, and O), or mixed-effects analysis followed by Tukey’s post hoc if applicable (I) with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Indirect regulation of VMHMC3R neurons is suggested by the observation that hypoglycemia inhibits nearly all VMHMC3R neurons, yet only a subset sensed glucose directly. Indeed, lowering glucose without synaptic blockade decreased the frequency and amplitude of spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic currents (sEPSCs) on VMHMC3R neurons, thus demonstrating indirect glucose-dependent regulation via presynaptic input (Fig. 1 M–O). There was no change in spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs).

Given these glucose-dependent alterations in excitatory input, we used monosynaptic retrograde tracing to inputs to VMHMC3R neurons. Projection-specific modified rabies virus tracing was performed in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), a site targeted by MC3R axons relevant for VMH-mediated blood glucose regulation (Fig. 1P) (2). BNST-projecting VMHMC3R neurons receive inputs from several brain areas relevant to glucose regulation including POMC cells of the ARC (Fig. 1S), and cells in the lateral parabrachial nucleus (lPBN) (Fig. 1W).

VMHMC3R Neurons Regulate Glucose Disposal.

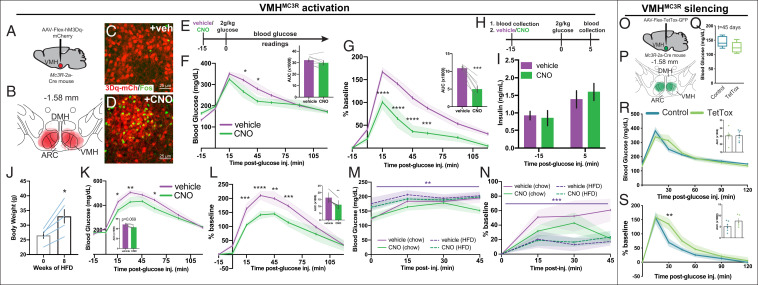

To directly test the capacity of VMHMC3R neurons to promote glucose disposal, we chemogenetically activated VMHMC3R neurons using the Cre-dependent modified human muscarinic receptor hM3Dq (AAV8-hSyn-Flex-hM3Dq-mCherry; Fig. 2 A–D) 15 min prior to a glucose tolerance test (GTT) (Fig. 2E). Preactivation of VMHMC3R neurons blunts glucose excursion in comparison to controls (Fig. 2 F and G). This effect appears to be largely independent of insulin secretion, as insulin is unchanged 5 min after glucose administration (Fig. 2 H and I).

VMHMC3R neuron activity alters glucose disposal. DREADD(hM3Dq)-mediated activation of VMHMC3R neurons (A and B) using i.p. CNO increases activation-induced Fos in the VMH (C and D). Preactivation of VMHMC3R neurons using hM3Dq blunts glucose excursion during a GTT (E–G; n = 7) without altering plasma insulin levels 5 min after glucose injection (H and I; n = 4). (J–L) Activation of VMHMC3R neurons promotes glucose disposal during HFD conditions. (M and N) While HFD-fed mice differ in baseline glucose levels compared to chow conditions (main effects of food and time without interaction, three-way ANOVA), activation of VMHMC3R neurons does not affect glucose disposal in chow or HFD mice (n = 4) absent a glucose load. Tetanus toxin silencing of VMHMC3R neurons (O and P) does not alter basal blood glucose (Q) and increases glucose excursion upon a glucose load (R and S) (TetTox, n = 5; control, n = 7–8). Significance was determined using a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (F, G, K, and L), paired t test (F, G, K, and L; AUC, J), two-way ANOVA (R and S), three-way ANOVA (M and N), or an unpaired t test (Q, R, and S, AUC), all with Tukey’s post hoc as applicable, with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

To test the potential benefit of activating VMHMC3R neurons in a glucose-intolerant state, we chemogenetically activated VMHMC3R neurons prior to a GTT in mice fed a 60% high-fat diet (HFD) (Fig. 2J). Preactivation of VMHMC3R neurons promotes glucose disposal in HFD conditions (Fig. 2 K and L), suggesting that driving VMHMC3R neuron activity may be sufficient to promote glucose disposal in glucose-intolerant states. Since VMHMC3R activation without a glucose load does not significantly alter peripheral glucose levels in mice on either chow or HFD conditions (Fig. 2 M and N), the effects of VMHMC3R neuronal activation may be most impactful during a glucose load.

To examine the contribution of VMHMC3R neurons to glucose homeostasis, we silenced these neurons using a Cre-dependent tetanus toxin (AAV8-hSyn-Flex-TetTox-GFP; Fig. 2 O and P). Loss of VMHMC3R neuronal activity does not alter blood glucose levels in the basal state (Fig. 2Q) but does increase blood glucose during a GTT (Fig. 2 R and S). VMHMC3R neuron silencing did not affect body weight or food intake (body weight at t = 45 d post injection [mean ± SEM]: TetTox, 30.4 ± 1.9 g; control, 29.6 ± 1.0 g; two-way ANOVA), suggesting that the impaired glucose handling was not secondary to obesity alone.

Discussion

The VMH regulates both glucose mobilization during the counterregulatory response and glucose disposal in response to hormonal factors (123–4). However, the cellular mechanisms coordinating these seemingly opposing physiologic functions are largely unknown. Here, we show that VMHMC3R neurons respond to melanocortin agonists and their activation promotes glucose disposal in both chow and HFD conditions. Silencing of VMHMC3R neurons disrupts normal glucose handling, underscoring an important role for these neurons in glucose homeostasis. These neurons sense glucose directly and indirectly via excitatory synaptic inputs, which potentially arise from ARC POMC neurons known to modulate blood glucose (10) and PBN neurons. VMHMC3R neurons do not directly respond to high glucose but appear situated to integrate input from upstream glucose sensing neurons and/or other stimuli to promote glucose uptake.

Activation of SF1-Cre VMH neurons (which represent most VMH neurons) mimics the counterregulatory response (CRR), suggesting that the autonomic and neuroendocrine effects on glucose mobilization during the CRR supersede the ability of peripheral tissues to dispose of glucose (2, 3). We show that VMHMC3R neurons are a subset of VMH cells that promote glucose disposal, a role opposing pan-VMH activation. Our results highlight a unique circuit node capable of lowering peripheral blood glucose in both normal and HFD conditions and demonstrate the importance of fine-tuned analysis of neural circuits in the assessment of discrete physiologic outputs. Taken together, VMHMC3R neurons may be a potential site for targeted therapies of dysregulated glycemia, including glucose intolerance and type II diabetes.

Methods

Animals.

Animals were bred and housed according to guidelines approved by the University of Michigan Committee on the Care and Use of Animals. Male mice (8–23 wk) were used for all behavioral studies. Mice were provided ad libitum food (standard chow, Purina Laboratory Diet 5001; 60% HFD, Research Diets D12492) and water, unless otherwise noted, and acclimatized to intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections 3 d prior to experimentation. Following experimentation, mice were perfused, immunohistochemistry (IHC) performed as previously described (11), and data points excluded if extra-VMH viral transduction occurred. IHC was performed for dsRed (Clontech), GFP (Invitrogen), Fos (Cell Signaling 9F6), and αMSH (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals).

Stereotaxic Injections.

Surgeries were performed as previously described (11). VMH-directed injections (25 nL/side) were performed relative to bregma (anteroposterior [A/P]: −1.0; mediolateral [M/L]: ± 0.25; dorsoventral [D/V]: −5.5). Mice recovered for at least 2 wk before testing. For rabies tracing, helper virus (11) was injected followed by EnvA-dB19G-rabies-mCh injections (BNST) (A/P: +0.65; M/L: +0.4; D/V: −3.8) 3 wk later. Mice were perfused and IHC performed 5 d after virus injection.

Electrophysiology.

Coronal slices (250 μM) were prepared from 4- to 12-wk-old Mc3R-2a-Cre, Td mice of either sex in oxygenated ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) solution containing the following (in mM): 125 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1.25 NaH2PO4, NaHCO3, 2 glucose, 1 MgCl2, and 2.5 CaCl2, plus 0.2 mM ascorbic acid and 1 mM kynurenic acid, pH 7.4, 300–305 mOsm, and allowed to recover ≥1 h (-kynurenic acid) at 33–34 °C. Patch-clamp recordings from VMHMC3R neurons were made using borosilicate electrodes (3–7 MΩ) filled with either perforated patch internal (in mM): 130 K gluconate, 10 KCl, 1 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 2 MgCl2, amphotericin B (0.15 mg/mL) for current-clamp recordings of Vm/AP firing in response to glucose (Fig. 1 F–J) or whole-cell internal solution (in mM): 130 K gluconate, 10 KCl, 1 EGTA, Hepes, 0.6 NaGTP, 2 MgATP, and 8 phosphocreatine, pH 7.2, 285–295 mOsm, for all other experiments. Slices were perfused with ACSF solution (33–34 °C, 1.5–2 mL/min) and bubbled with 5% CO2/95% O2. When stated, synaptic input and AP firing were blocked by inclusion of 1 µM tetrodotoxin, 20 µM d-APV, 10 µM CNQX, and 50 µM picrotoxin. Spontaneous EPSCs and IPSCs were measured from neurons voltage clamped to −50 mV, producing inward sEPSCs and outward sIPSCs, and analyzed using Synaptosoft software. Data were not corrected for a junction potential of ∼15 mV. Analyzed neurons had uncompensated stable series resistances (<30 MΩ).

GTT.

Following a 4-h fast, mice were injected with glucose (2 g/kg, i.p.), and blood glucose monitored by tail vein (OneTouch Ultra 2 glucometer). For hM3Dq experiments, mice received vehicle (10% β-cyclodextran) or CNO (0.3 mg/kg) 15 min prior to glucose administration counterbalanced across at least 1 wk. Insulin analysis was performed in a separate experiment using blood collected via tail vein; insulin levels were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Crystal Chem). Separate experiments were performed with 60% HFD (Research Diets).

VMHMC3R Silencing.

Mc3R-2a-Cre mice were injected with AAV8-hSyn-Flex-TetTox and compared to two control groups: Mc3R-2a-Cre mice + AAV8-hSyn-Flex-GFP, or WT mice + AAV8-hSyn-Flex-TetTox, which showed no statistical difference on any measured variable and were pooled into one control group. GTT was performed 3 wk postsurgery.

Statistical Analyses.

Paired and unpaired t tests, one-way, two-way, or three-way ANOVAs followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons (if applicable), or mixed model analyses were calculated using GraphPad Prism 8 as appropriate, with significance denoted at P < 0.05.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Melanocortin 3 receptor-expressing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus promote glucose disposal

Melanocortin 3 receptor-expressing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus promote glucose disposal