Edited by William A. Eaton, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, and approved February 17, 2021 (received for review September 13, 2020)

Author contributions: K.L.S., A.S.M., and T.P.J.K. designed research; K.L.S. and A.S.M. performed research; K.L.S., A.S.M., and R.Q. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; K.L.S. and A.S.M. analyzed data; K.L.S., A.S.M., and T.P.J.K. wrote the paper; and W.E.A., G.K., and A.A.L. discussed the results and reviewed the manuscript.

1K.L.S. and A.S.M. contributed equally to this work.

2Present address: Fluidic Analytics, Unit A, The Paddocks Business Centre, Cambridge CB1 8DH, United Kingdom.

- Altmetric

The tendency of many cellular proteins to form protein-rich biomolecular condensates underlies the formation of subcellular compartments and has been linked to various physiological functions. Understanding the molecular basis of this fundamental process and predicting protein phase behavior have therefore become important objectives. To develop a global understanding of how protein sequence determines its phase behavior, we constructed bespoke datasets of proteins of varying phase separation propensity and identified explicit biophysical and sequence-specific features common to phase-separating proteins. Moreover, by combining this insight with neural network-based sequence embeddings, we trained machine-learning classifiers that identified phase-separating sequences with high accuracy, including from independent external test data.

Intracellular phase separation of proteins into biomolecular condensates is increasingly recognized as a process with a key role in cellular compartmentalization and regulation. Different hypotheses about the parameters that determine the tendency of proteins to form condensates have been proposed, with some of them probed experimentally through the use of constructs generated by sequence alterations. To broaden the scope of these observations, we established an in silico strategy for understanding on a global level the associations between protein sequence and phase behavior and further constructed machine-learning models for predicting protein liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS). Our analysis highlighted that LLPS-prone proteins are more disordered, less hydrophobic, and of lower Shannon entropy than sequences in the Protein Data Bank or the Swiss-Prot database and that they show a fine balance in their relative content of polar and hydrophobic residues. To further learn in a hypothesis-free manner the sequence features underpinning LLPS, we trained a neural network-based language model and found that a classifier constructed on such embeddings learned the underlying principles of phase behavior at a comparable accuracy to a classifier that used knowledge-based features. By combining knowledge-based features with unsupervised embeddings, we generated an integrated model that distinguished LLPS-prone sequences both from structured proteins and from unstructured proteins with a lower LLPS propensity and further identified such sequences from the human proteome at a high accuracy. These results provide a platform rooted in molecular principles for understanding protein phase behavior. The predictor, termed DeePhase, is accessible from https://deephase.ch.cam.ac.uk/.

Liquid–liquid phase separation (LLPS) is a widely occurring biomolecular process that underpins the formation of membraneless organelles within living cells (123–4). This phenomenon and the resulting condensate bodies are increasingly recognized to play important roles in a wide range of biological processes, including the onset and development of metabolic diseases and cancer (5678910–11). Understanding the factors that drive the formation of protein-rich biomolecular condensates has thus become an important objective and been the focus of a large number of studies, which have collectively yielded valuable information about the factors that govern protein phase behavior (3, 4, 12, 13).

While changes in extrinsic conditions, such as temperature, ionic strength, or the level of molecular crowding, can strongly modulate LLPS (141516–17), of fundamental importance to condensate formation is the linear amino acid sequence of a protein, its primary structure. A range of sequence-specific factors governing the formation of protein condensates have been postulated with electrostatic interactions, –

To broaden the scope of these observations and understand on a global level the associations between the primary structure of a protein and its tendency to form condensates, here, we developed an in silico strategy for analyzing the associations between LLPS propensity of a protein and its amino acid sequence and used this information to construct machine-learning classifiers for predicting LLPS propensity from the amino acid sequence (Fig. 1). Specifically, by starting with a previously published LLPSDB database collating information on protein phase behavior under different environmental conditions (27) and by analyzing the concentration under which LLPS had been observed to take place in these experiments, we constructed two datasets including sequences of different LLPS propensity and compared them to fully ordered structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) (29) as well as the Swiss-Prot (30) database. We observed phase-separating proteins to be more hydrophobic, more disordered, and of lower Shannon entropy and have their low-complexity regions enriched in polar residues. Moreover, high LLPS propensity correlated with high abundance of polar residues yet the lowest saturation concentrations were reached when their abundance was balanced with a sufficiently high hydrophobic content.

![(A) DeePhase predicts the propensity of proteins to undergo phase separation by combining engineered features computed directly from protein sequences with protein sequence embedding vectors generated using a pretrained language model. The DeePhase model was trained using three datasets, namely two classes of intrinsically disordered proteins with a different LLPS propensity (LLPS+ and LLPS−) and a set of structured sequences (PDB*). (B) To generate the LLPS+ and LLPS− datasets, the entries in the LLPSDB database (27) were filtered for single-protein systems. The constructs that phase separated at an average concentration below c = 100 μM were classified as having a high LLPS propensity (LLPS+; 137 constructs from 77 UniProt IDs) with the remaining 25 constructs together with constructs that had not been observed to phase separate homotypically classified as low-propensity dataset (LLPS−; 84 constructs from 52 UniProt IDs). (C) The 221 sequences clustered into 123 different clusters [Left, CD-hit clustering algorithm (28) with the lowest threshold of 0.4]. (Right) The 110 parent sequences showed high diversity by forming 94 distinct clusters. (D) The PDB* dataset (1,563 constructs) was constructed by filtering the entries in the PDB (29) to fully structured full-protein single chains and clustering for sequence similarity with a single entry selected from each cluster.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766059973724-d4d8d4a2-f3af-4190-984e-40dc63c7876a/assets/pnas.2019053118fig01.jpg)

(A) DeePhase predicts the propensity of proteins to undergo phase separation by combining engineered features computed directly from protein sequences with protein sequence embedding vectors generated using a pretrained language model. The DeePhase model was trained using three datasets, namely two classes of intrinsically disordered proteins with a different LLPS propensity (

Moreover, we used the outlined sequence-specific features as well as implicit protein sequence embeddings generated using a neural network-derived word2vec model and trained classifiers for predicting the propensity of unseen proteins to phase separate. We showed that even though the latter strategy required no specific feature engineering, it allowed constructing classifiers that were comparably effective at identifying LLPS-prone sequences as the model that used knowledge-based features, demonstrating that language models can learn the molecular grammar of phase separation. Our final model, combining knowledge-based features with unsupervised embeddings, showed a high performance both when distinguishing LLPS-prone proteins from structured ones and when identifying them within the human proteome. Overall, our results shed light onto the physicochemical factors modulating protein condensate formation and provide a platform rooted in molecular principles for the prediction of protein phase behavior.

Results and Discussion

Construction of Datasets and Their Global Sequence Comparison.

To link the amino acid sequence of a protein to its tendency to form biomolecular condensates, we collated data from two publicly available datasets, the LLPSDB (27) and the PDB (29), and constructed three bespoke datasets—

An additional dataset,

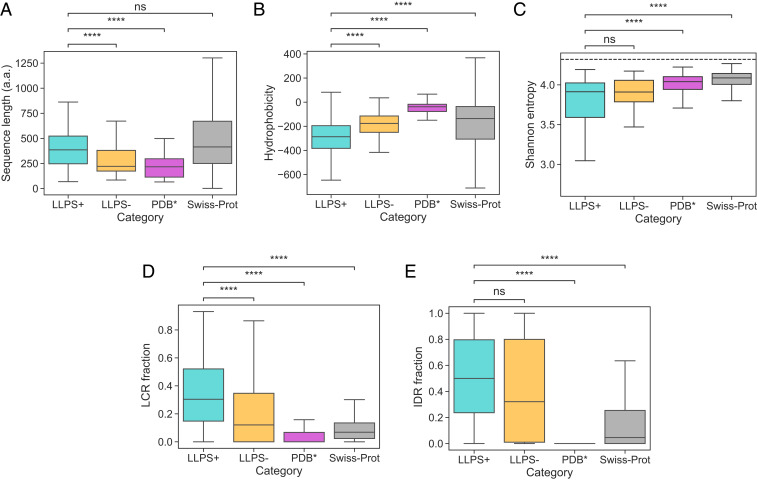

We compared the generated datasets across a range of global sequence-specific features with the aim to understand the factors that are linked with enhanced condensate formation propensity using the Swiss-Prot database (30) as a reference control (Fig. 2 A–E; full distributions are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S1). From the analysis, we first concluded that the average construct in the

(A–E) Comparison of the (A) sequence length (in amino acids, a.a.), (B) hydrophobicity, (C) Shannon entropy, the fraction of sequence that is part of (D) the low-complexity regions (LCRs) and (E) the intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) for the three training datasets and the Swiss-Prot. Comparative analysis highlighted that the average construct in the

To understand how sequence complexity and the extent of disorder were linked to the tendency of proteins to undergo phase separation, we employed the SEG algorithm (32) to extract LCRs for all of the sequences in the four datasets and the IUPred2 algorithm (33) to identify their disordered regions (Materials and Methods). This analysis revealed that constructs in the

Amino Acid Composition of the Constructs Undergoing LLPS.

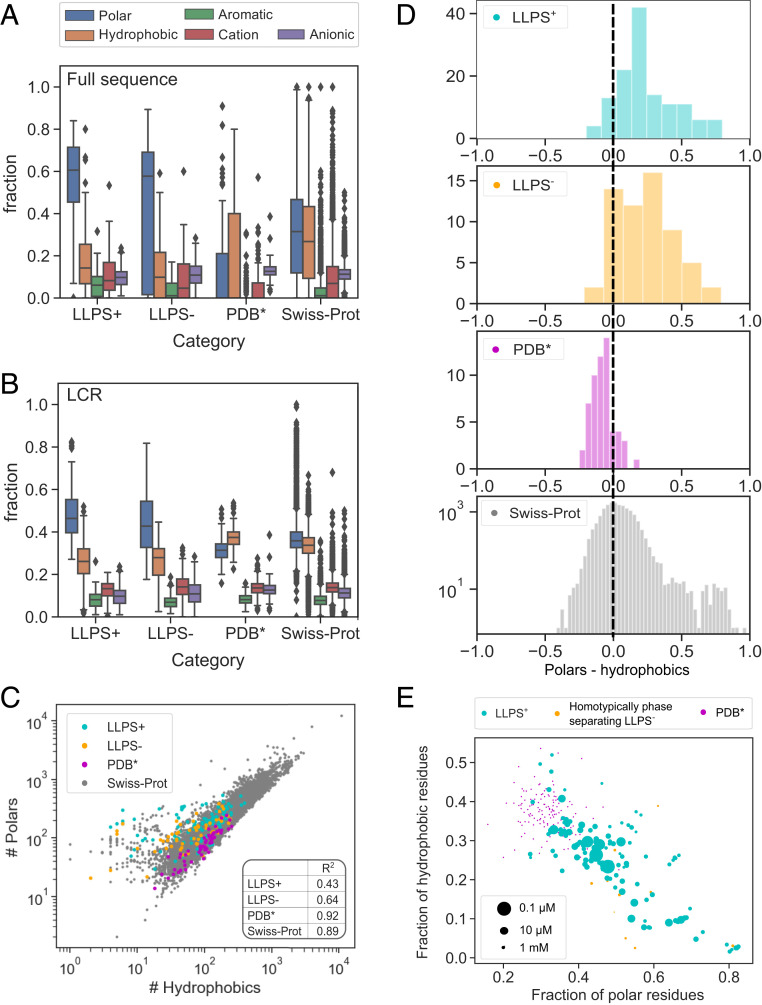

Having ascertained the length of the low-complexity and intrinsically disordered regions as basic parameters that set the constructed datasets apart (Fig. 2), we next set out to analyze the amino acid composition of these regions. By classifying the amino acid residues into polar, hydrophobic, aromatic, cationic, and anionic categories (Materials and Methods), we observed that the propensity of proteins to undergo LLPS was associated with a higher relative content of polar (blue) and a reduced relative content of hydrophobic (orange) and anionic (purple) residues across the full amino acid sequence (Fig. 3A). The increased abundance of polar residues was particularly pronounced within the LCRs with aromatic (green) and cationic (red) residues also being overrepresented within these regions compared to the sequences in the Swiss-Prot database (Fig. 3B), consistent with previous observations and findings (18, 21). Moreover, we observed that not only are sequences with a high LLPS propensity enriched in polar residues; they also showed a much less tightly conserved relationship between polar and hydrophobic residues (Fig. 3C). The high relative abundance of hydrophobic residues and their narrowly defined fraction are likely linked to the requirement of a hydrophobic core underpinning the more structured nature of the proteins in the

Comparison of the amino acid composition of the sequences within the

Since the high abundance of polar residues relative to hydrophobic ones clearly correlated with elevated LLPS propensity (Fig. 3D), we next aimed to explore whether a very high content of polar residues affects protein phase behavior. This analysis was motivated by associative polymer theory and the “spacers and sticker” framework (21) whereby the formation of intermolecular interactions and the onset of protein phase separation are facilitated by an interplay between “spacer” and “sticker” regions. To this effect, we first evaluated the saturation concentrations of all of the 149 constructs that had been seen to undergo homotypic phase separation (Fig. 1B) as the lowest concentration at which the particular construct had been seen to phase separate. We then used these estimates to examine how the saturation concentration varied with the amino acid composition of the protein (Fig. 3E). We also included proteins in the

Model for Classifying the Propensity of Unseen Sequences to Phase Separate.

We next developed machine-learning classifiers that could predict the propensity of proteins to undergo phase separation using the constructed datasets (

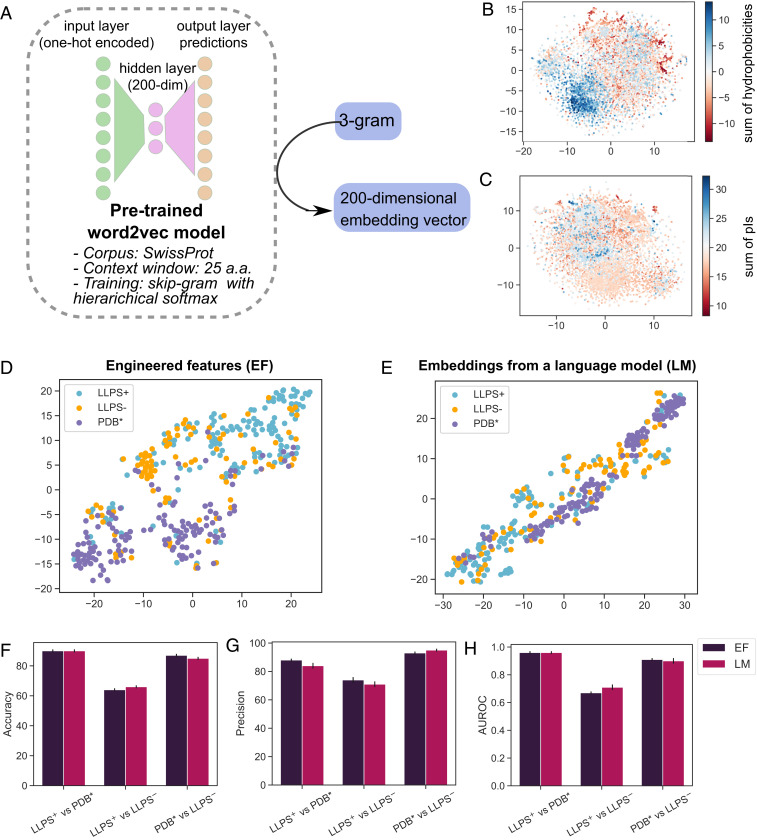

(A) A single-hidden-layer language model (LM) was pretrained to learn embedding vectors for each amino acid 3-gram (Materials and Methods). The generated embedding vectors clustered 3-grams according to their (B) hydrophobicity (evaluated as the sum of the Kyte and Doolittle hydrophobicity values of the individual amino acids in the 3-gram) and (C) isoelectric point (pI; sum of the pI values of the individual amino acids). Dimensionality reduction from the 200-dimensional vectors to the 2D plane was performed with the Multicore-TSNE library (35). Visualizing the similarity of the sequences in the

We used a dimensionality reduction approach (35) to visualize the feature vectors of all of the data points in the training data on a 2D plane both for the case when EFs (sequence length, hydrophobicity, Shannon entropy, the fraction of the sequence identified to be part of the LCRs and IDRs [Fig. 2] and the fraction of polar, aromatic, and cationic amino acid residues within the LCRs [Fig. 3]) and the word2vec-based embeddings were used (Fig. 4 D–E). This process revealed a notable degree of separation between the

We next set out to gain an insight into how well these two feature types could distinguish between the three classes of proteins. Specifically, we trained random forest classifiers for each of the three pairs of data and estimated their performance using a 25-fold cross-validation test with 20% of the data left out for validation each time (Materials and Methods). For the cases when

Performance of the Models on an External Dataset.

Having established the high cross-validation performance of the models within our generated datasets, we set out to test the models on external test data. Specifically, we evaluated their capability on two tasks: 1) distinguishing sequences with a high LLPS propensity from sequences very unlikely to undergo phase separation and 2) identifying LLPS-prone sequences from within the human proteome.

First, to construct an external set of LLPS-prone proteins, we used the PhaSepDB (36) database. After removing from this database the UniProt IDs that overlapped with any of the LLPSDB entries and hence with our training data, we obtained a set of 196 LLPS-prone human sequences (Dataset S5). A further examination of these 196 sequences highlighted that 35 of them included no intrinsically disorder regions. In general, it is known that while fully structured proteins can in principle undergo phase separation, they usually do so at high concentrations and would hence not normally be regarded as LLPS prone (37). To validate this trend, we examined the LLPSDB database (used for constructing the training datasets) where the phase behavior of all of the protein constructs was listed together with environmental conditions. This analysis revealed that all of the experiments in which a fully structured protein had been observed to be phase separated were performed under an extensive amount of molecular crowding (e.g., dextran, ficoll, polyethylene glycol) or in a nonhomotypical environment (e.g., in the presence of lipids). It is thus likely that the fully ordered sequences within the PhaSepDB that were identified as phase separating in a keyword-based literature search similarly phase separated under high concentrations, nonhomotypical conditions, or a notable level of molecular crowding, and their phase transition cannot be directly linked to the protein sequence as it was not triggered exclusively by homotypic interactions between protein molecules. Motivated by this argument, we eliminated fully structured sequences, which yielded a list of 161 sequences serving as our external test data (Dataset S6). The set of proteins highly unlikely to undergo phase separation (Dataset S7) was created by random sampling an equal number (161) of sequences from the

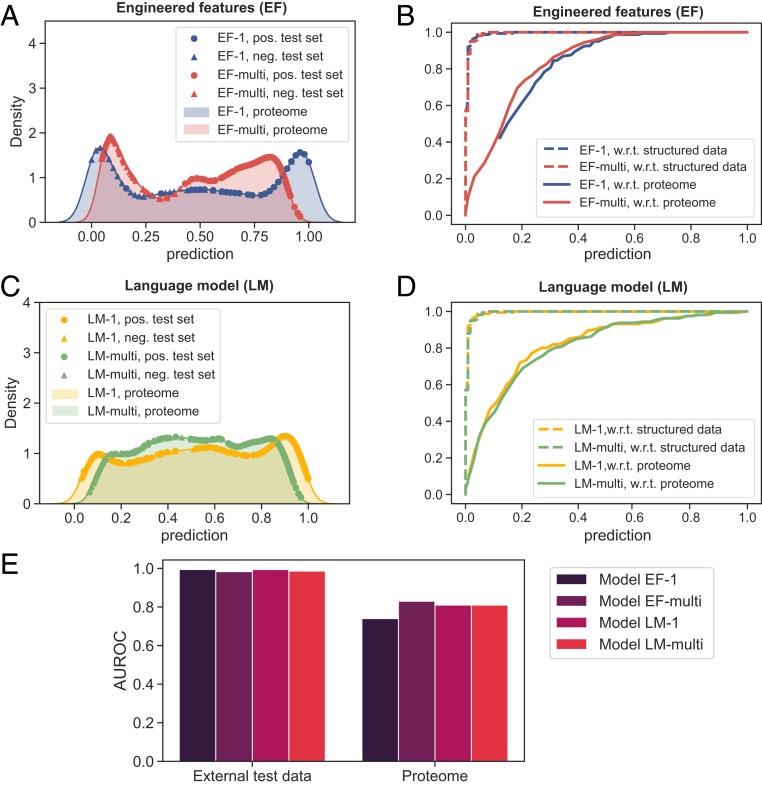

Performance of the models on external data when 1) discriminating between LLPS-prone sequences and structured proteins and 2) identifying LLPS-prone proteins from the human proteome. (A) The prediction profiles of model EF-1 (trained on

Additionally, we set out to gain an insight into the capability of the models to identify LLPS-prone sequences from the human proteome. As the phase behavior of many proteins remains unstudied, it is challenging to generate a dataset of nonstructured proteins that do not undergo phase separation. To obtain an estimate of the rate of false negative predictions of the models when identifying LLPS-prone sequences, we relied on the exhaustive keyword-based literature search performed as part of the construction of the PhaSepDB database (36). This database was curated by extracting all publications from the NCBI PubMed database that included phase separation-related keywords in their abstracts. The resulting 2,763 papers were manually rechecked to obtain publications that described membraneless organelles and related proteins, and they were further manually filtered to these proteins that had been observed to undergo phase separation experimentally either in vitro or in vivo. Making a conservative assumption that all of the proteins that were not identified as LLPS positive through this PubMed search are nonphase separating, we could estimate an upper bound for the false positive rate of each of the models in identifying LLPS-prone sequences. The approximated ROC curves with respect to (w.r.t.) proteome are shown in Fig. 5 B and D, solid lines. All of the four models showed a notable predictive performance with the AUROCs w.r.t. proteome varying between 0.74 and 0.81 (Fig. 5E). This performance is in contrast to control experiments where, prior to training the models, the labels of the sequences were randomly reshuffled (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) and the actual sequence compositions were replaced by randomly sampling amino acids from the Swiss-Prot database (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). All in all, the results indicate that our models can distinguish between LLPS-prone and structured ones and they can also identify LLPS-prone proteins from within the human proteome. These results also highlight that w2v-based featurization creates meaningful low-dimensional representations that can be used for building classifiers for downstream tasks, in this case, for the prediction of protein phase behavior, without requiring prior insight into the features that govern the process.

Comparison of Explicitly Engineered Features and Learned Embeddings.

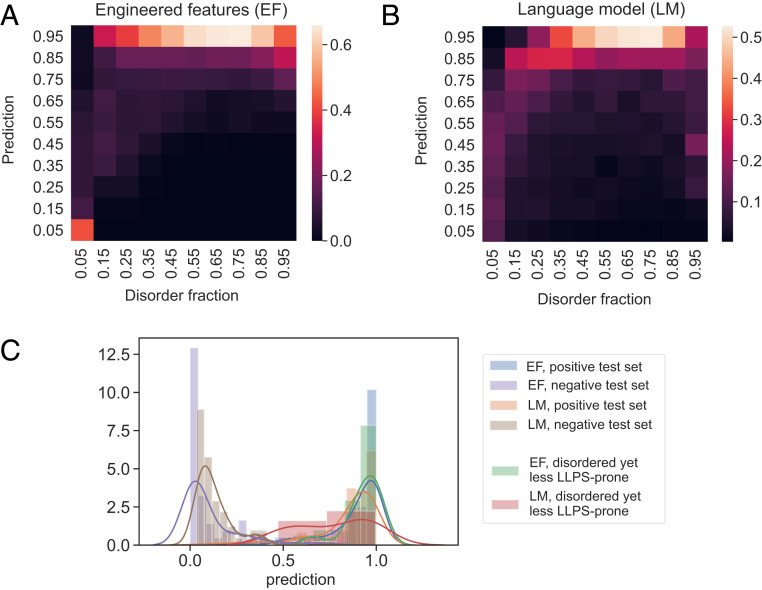

The use of two distinct featurization approaches—one that used only knowledge-based features and another one that relied on hypothesis-free embedding vectors—provided us with the opportunity to investigate whether, in addition to being able to predict LLPS propensity, language models can also learn the underlying features of protein condensate formation. The prediction profiles of the different models shown in Fig. 5 suggest that the difference between the two featurization approaches was most pronounced when only

First, we noticed that when the predictions of the models were binned by intrinsic disorder, the predictions correlated with the degree of disorder for both models (Fig. 6 A and B; data across the full human proteome). While this correlation was not unexpected for model EF-1 for which disorder was an explicit input feature, the presence of such a correlation in the case of LM-1 suggested that not only can language models predict LLPS propensity, they also can capture information about the biophysical features underpinning this process. Second, we hypothesized that a key difference between models EF-1 and LM-1—whether or not disorder was used as an explicit input feature—may equip LM-1 with an enhanced capability to discriminate between disordered sequences of varying LLPS propensity. We tested this hypothesis by examining the predictions of the two models on highly disordered sequences (IDR fraction above 0.5) from the low LLPS-propensity dataset,

Comparison of the models constructed using EFs and embedding vectors extracted from a LM. (A and B) The predicted LLPS-propensity score correlated with the disorder content when both EF- and LM-based embeddings were used. This trend indicated the language model was able to learn a key underlying feature associated with a high LLPS propensity. (C) The prediction profiles of models EF-1 and LM-1 on LLPS-prone sequences (external positive test set), structured sequences (external negative test set), and disordered sequences with a low LLPS propensity (sequences with IDR fraction above 0.5 that were part of the

DeePhase Model.

Finally, with models EF-multi and LM-multi using different input features but still demonstrating comparably good performance, we created our final model, termed DeePhase, where the prediction on every sequence was set to be the average prediction made by the two models. As expected, the models could effectively distinguish between the LLPS-prone and the structured proteins in the external test dataset (Fig. 7A; cyan and pink regions; AUROC of 0.99). When identifying LLPS-prone sequences from the human proteome (cyan and gray regions) as outlined earlier, AUROC of 0.84 was reached, which was comparable to or slightly exceeded what models EF-multi (0.83) and LM-multi (0.81) achieved on their own.

![Generalizability of DeePhase to evolutionarily nonrelated sequences and comparison to previously developed LLPS predictors. (A) DeePhase prediction profile on the human proteome (gray), on the external test data (161 LLPS-prone [cyan] and 161 structured proteins [pink]), and on a set of 73 artificial peptides that have been experimentally validated to be phase separate (38) (yellow). DeePhase allocated a high LLPS-propensity score for the latter dataset, indicating that its capability to evaluate phase behavior extends to evolutionary nonrelated sequences. (B) Comparison of DeePhase to CatGRANULE and PScore, the algorithms that were recently found to be the best performing for LLPS prediction (23), when identifying LLPS-prone sequences from the human proteome. For a reliable comparison, sequences were filtered for a length of 140 residues or above as this is the lowest threshold at which the PScore can be evaluated.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766059973724-d4d8d4a2-f3af-4190-984e-40dc63c7876a/assets/pnas.2019053118fig07.jpg)

Generalizability of DeePhase to evolutionarily nonrelated sequences and comparison to previously developed LLPS predictors. (A) DeePhase prediction profile on the human proteome (gray), on the external test data (161 LLPS-prone [cyan] and 161 structured proteins [pink]), and on a set of 73 artificial peptides that have been experimentally validated to be phase separate (38) (yellow). DeePhase allocated a high LLPS-propensity score for the latter dataset, indicating that its capability to evaluate phase behavior extends to evolutionary nonrelated sequences. (B) Comparison of DeePhase to CatGRANULE and PScore, the algorithms that were recently found to be the best performing for LLPS prediction (23), when identifying LLPS-prone sequences from the human proteome. For a reliable comparison, sequences were filtered for a length of 140 residues or above as this is the lowest threshold at which the PScore can be evaluated.

To further investigate the generalizability of DeePhase, we analyzed its performance after reducing the external dataset only to sequences that showed low similarity with the training data. Specifically, by clustering the external test and training data together [CD-hit algorithm (28), the lowest threshold of 0.4] and retaining only these test sequences that did not cocluster with any of the constructs in the training set, the external dataset was reduced from 161 sequences down to 109. With this reduction, AUROC w.r.t. the proteome dropped from 0.84 to 0.83, illustrating that the performance of DeePhase generalizes with regard to the sequences that do not share high sequence similarity with the training set. To test the limits of the DeePhase model further still, we also evaluated the LLPS-propensity score of a set of 73 artificial proteins that had experimentally been observed to phase separate in an earlier study (Dataset S8) (38). These constructs were not evolutionarily related to the sequences in our training set, yet DeePhase allocated a high LLPS propensity to them all (Fig. 7A, yellow).

To conclude, we compared the performance of DeePhase to two previously developed algorithms, PScore and CatGranule that had recently been identified as the best-performing algorithms for evaluating LLPS propensity of proteins in a comparative study (23). As the use of the PScore algorithm is limited to sequences that are longer than 140 residues we removed sequences shorter than this threshold value, which reduced the size of the proteome down to 18,473 sequences. On this dataset, the AUROC of DeePhase w.r.t. the proteome was 0.83, exceeding by over 10% what was achieved by the CatGRANULE and PScore models (Fig. 7B). We note that the comparison was constructed in a manner where it was ensured it would not favor the DeePhase model as any LLPS-prone sequences that DeePhase encountered during the training process had been excluded.

Conclusion

To understand how protein sequence governs its phase behavior and build an algorithm for predicting LLPS-prone sequences, we constructed datasets of proteins of varying LLPS propensity. The analysis of the curated datasets highlighted that LLPS-prone sequences were less hydrophobic and had a higher degree of disorder and a lower Shannon entropy than an average protein in the Swiss-Prot database. Furthermore, our analysis of the amino acid compositions indicated that while LLPS-prone sequences were enriched in polar residues, the lowest saturation concentrations were reached when their abundance was balanced by hydrophobic residues. Relying on the generated datasets, we used the identified features as well as hypothesis-free embedding vectors generated by a language model to construct machine-learning classifiers for predicting protein phase behavior. We observed that the model built on unsupervised embedding vectors was able to predict LLPS propensity at a comparable accuracy to a model that relied on knowledge-based features, demonstrating the capability of language models to learn the molecular grammar of phase protein phase behavior. DeePhase, our final model that combined engineered features with unsupervised embeddings, showed a high performance both when distinguishing LLPS-prone proteins from structured ones and when identifying them within the human proteome, establishing a framework rooted in molecular principles for predicting of protein phase behavior.

Materials and Methods

Construction of the L L P S + L L P S −

The

For each of the constructs, the experiments where the construct had been observed to phase separate were combined and the average concentration at which these positive experiments were performed was evaluated. When the latter concentration was below

Construction of the P D B *

Entries in the PDB (29) were used to generate a diverse set of proteins highly unlikely to undergo LLPS. Specifically, first, amino acid chains that were fully structured (i.e., did not include any disordered residues) were extracted, which resulted in a total of 112,572 chains. PDB chains were matched to their corresponding UniProt IDs using Structure Integration with Function, Taxonomy and Sequence service by the European Bioinformatics Institute, and entries where sequence length did not match were discarded. Duplicate entries were removed and the remaining 13,325 chains were clustered for their sequence identity using a conservative cutoff of 30%. One sequence from each cluster was selected, resulting in the final dataset of 1,563 sequences.

Estimation of Physical Features from the Sequences.

A range of explicit physicochemical features was extracted for all of the sequences in the four datasets from their amino acid sequences (

Finally, the amino acid sequence and the LCRs were described for their amino acid content by allocating the residues to the following groups: amino acids with polar residues (serine, glutamine, asparagine, glycine, cysteine, threonine, proline), with hydrophobic residues (alanine, isoleucine, leucine, methionine, phenylalanine, valine), with aromatic residues (tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine), with cationic residues (lysine, arginine, histidine), and with anionic residues (aspartic acid, glutamic acid).

Protein Sequence Embeddings.

Protein sequence embeddings were evaluated using a pretrained word2vec model. Specifically, the pretraining was performed on the full Swiss-Prot database (accessed on 26 Jun 2020) using 3-grams as words and a context window size of 25—parameters that have been previously shown to work effectively when predicting protein properties via transfer learning (34). The skip-gram pretraining procedure with negative sampling was used and implemented using the Python gensim library (39) with its default settings. This pretraining process created 200-dimensional embedding vectors for every 3-gram. To evaluate the embedding vectors for the protein, each protein sequence was broken into 3-grams using all three possible reading frames and the final 200-dimensional protein embeddings were obtained by summing all of the constituent 3-gram embeddings.

Machine-Learning Classifier Training and Performance Estimation.

All classifiers were built using the Python scikit-learn package (40) with default parameters. No hyperparameter tuning was performed for any of the models—while such a tuning step may have given an improvement in accuracy, it can also lead to an overfitted model that does not generalize well to unseen data. For performing the training, the dataset was split into a train and a validation test in a 1

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the Schmidt Science Fellows program in partnership with the Rhodes Trust (K.L.S.), a St John’s College Junior Research Fellowship (to K.L.S.), a Trinity College Krishnan-Ang Studentship (to R.Q.) and the Honorary Trinity-Henry Barlow Scholarship (to R.Q.), the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Centre for Doctoral Training in NanoScience and Nanotechnology (NanoDTC) (EP/L015978/1 to W.E.A.), the EPSRC Impact Acceleration Program (W.E.A., G.K., T.P.J.K.), the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Program through the Marie Sklodowska-Curie Grant MicroSPARK (Agreement 841466 to G.K.), the Herchel Smith Fund of the University of Cambridge (to G.K.), a Wolfson College Junior Research Fellowship (to G.K.), the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013) through the European Research Council Grant PhysProt (Agreement 337969 to T.P.J.K.), and the Newman Foundation (T.P.J.K.).

Data Availability

The data and code are available from GitHub, https://github.com/kadiliissaar/deephase. All the data is also included in Datasets S1–S8

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

Learning the molecular grammar of protein condensates from sequence determinants and embeddings

Learning the molecular grammar of protein condensates from sequence determinants and embeddings