- Altmetric

Capturing virus aerosols in a small volume of liquid is essential when monitoring airborne viruses. As such, aerosol-to-hydrosol enrichment is required to produce a detectable viral sample for real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) assays. To meet this requirement, the efficient and non-destructive collection of airborne virus particles is needed, while the incoming air flow rate should be sufficiently high to quickly collect a large number of virus particles. To achieve this, we introduced a high air flow-rate electrostatic sampler (HAFES) that collected virus aerosols (human coronavirus 229E, influenza A virus subtypes H1N1 and H3N2, and bacteriophage MS2) in a continuously flowing liquid. Viral collection efficiency was evaluated using aerosol particle counts, while viral recovery rates were assessed using real-time qRT-PCR and plaque assays. An air sampling period of 20 min was sufficient to produce a sample suitable for use in real-time qRT-PCR in a viral epidemic scenario.

Introduction

Historically, zoonoses derived from livestock and animals have been the cause of a significant loss of human life and generated severe social costs, though the development of biomedical technology, including the production of antibody drugs and vaccines, has reduced the impact of these infectious diseases to some extent. However, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), influenza A virus (H1N1), and the novel coronavirus appeared in 2019 (SARS-CoV2) are a collection of strongly infectious viruses that continue to mutate. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that there have been 9.2–35.6 million cases of influenza, 140,000–710,000 hospitalizations, and 12,000–56,000 deaths annually since 2010 (CDC, 2020).

The monitoring of biological particles suspended in the air has been used for decades to prevent large-scale outbreaks of infection. Real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR), an assay designed for microbes that works by amplifying a target gene, is the most widely used method for monitoring airborne viruses due to its reliability. Before the assay can be conducted, however, virus aerosols need to be captured in a liquid because liquid samples are required for most bioanalytical approaches (e.g., nucleic acid detection, immunoassays, and cell culturing).

For the rapid monitoring of airborne viruses, it is essential to develop an air sampler that can collect airborne viruses dispersed in the air at very low concentrations and transfer them into a small volume of liquid above the limit of detection (LOD) for real-time qRT-PCR. The enrichment capacity (EC) of aerosol-to-hydrosol (ATH) sampling is an indicator of how many airborne virus particles can be amassed in this small volume of liquid. Thus, a high EC can reduce the time required to produce a detectable virus sample for use in real-time qRT-PCR. In Eq. (1), denotes the EC of ATH sampling (Kim et al., 2020a, Kim et al., 2020b):

During the air sampling process, airborne virus particles can be damaged by mechanical or chemical stress, rendering them undetectable and leading to a longer sampling time in order to produce a detectable sample, which hinders the rapid monitoring of airborne viruses (Piri et al., 2020, Kim et al., 2018). Therefore, the sampling of airborne virus particles for biosensors and bioassays, including real-time qRT-PCR, needs to be non-destructive, which can be quantified using the recovery rate (R):

The SKC BioSampler (SKC Inc., USA) is a widely used ATH sampler that captures airborne biological particles in a liquid (20 mL) using mechanical impaction. However, it has been experimentally proven that the collection efficiency of the SKC BioSampler for nano-sized viruses is less than 50% at a relatively low air sampling flow rate of 12.5 L/min (Li et al., 2018). For example, the

Therefore, the air flow rate, viral collection efficiency, and recovery rate of the collected viruses need to be high. This study proposes a high air flow-rate electrostatic air sampler (HAFES) than can achieve an

Materials and methods

Generation and sampling of test viruses

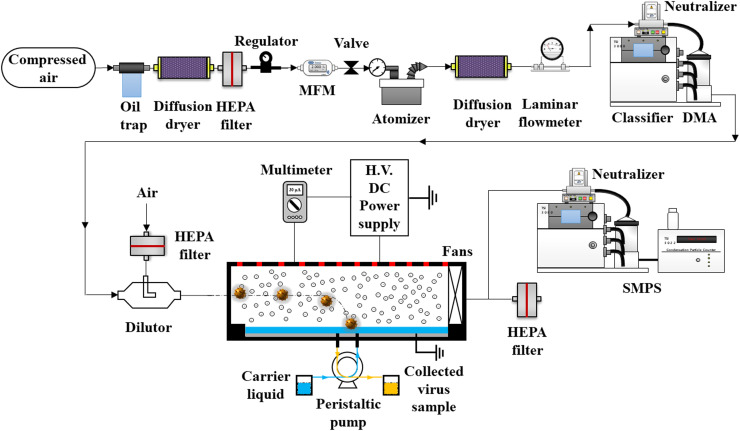

Fig. 1 presents the experimental setup for the virus collection tests using the HAFES. In this study, HCoV-229E (Korea Bank for Pathogenic Viruses, Korea), A/H1N1, A/H3N2 (H-GUARD, Korea), and the MS2 bacteriophage (KORAM Lab-Tech, Korea) were used as test aerosols. Sodium chloride (NaCl; S7653, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was also used as an aerosol to test the efficiency of size-dependent particle collection. NaCl has been used as a standard material for evaluating particle collection performance of an electrostatic air sampler (Miller et al., 2010, Han et al., 2009, Mainelis et al., 2002). The prepared virus stocks were mixed with deionized water (total volume of 50 mL), and the mixture was atomized using a Collison-type atomizer (9302, TSI Inc., USA). The flow rate of clean compressed air through the atomizer was 2 L/min. A diffusion dryer was used to eliminate moisture from the aerosolized virus particles. The particles passed through a neutralizer (Soft X-ray Charger 4530, HTC, Korea) to generate a Boltzmann charge distribution. The neutralized virus particles entered a differential mobility analyzer (DMA, 3081, TSI Inc., USA). The various-sized virus particles entering the DMA were sorted by size with a classifier (3080, TSI Inc., USA). Using the panel mode (a mode for selectively generating particles of desired size) of the classifier, virus particles of desired size were selectively generated. The selectively generated virus particle sizes were 28, 95, 95, and 109 nm, respectively, for MS2 phage, A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and HCoV-229E. These were similar to those of TEM images (see Section 3.1). The selectively generated virus particles entered the HAFES after 2 L/min of particle-laden air flow had been diluted with clean air. The total air flow rate (40–100 L/min) entering the HAFES was controlled by two fans. In the Section 3 of Supplementary Information, a method for generating the NaCl particles is described in detail.

Experimental setup for the evaluation of airborne virus collection performance of a high air flow-rate electrostatic air sampler (HAFES).

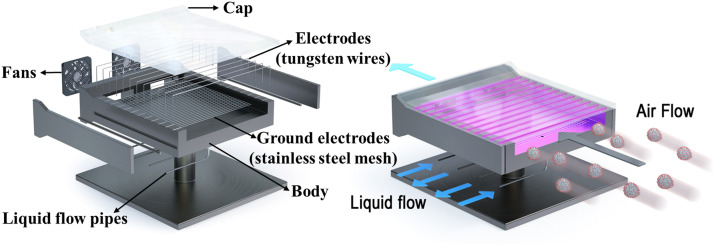

A 3D model of the proposed HAFES is presented in Fig. 2. The HAFES contained a cap with 12 tungsten-wire electrodes and a body with an air flow inlet and an outlet. The aerosolized virus and NaCl particles entering the HAFES were charged by ions generated on the surface of the discharge electrodes (the tungsten wires) via corona discharge. The charged particles were collected on the ground electrode (stainless-steel mesh) covered by phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, PR2004-100-72, Biosesang, Korea). PBS was continuously supplied through two inlet pipes and the collected virus sample was simultaneously flushed out through two outlet pipes using a peristaltic pump (ISM4408, Ismatec, Germany) with a flow rate of 200 μL/min (Fig. 1).

3D schematic of the proposed high air flow-rate electrostatic sampler (HAFES).

Corona currents were measured under various air flow rates and applied voltages using a multimeter (8845a, Fluke, USA). I–V measurements were repeated three times. The electrostatic module of COMSOL Multiphysics (Version 5.4) was employed to simulate the electrical potential in the HAFES.

The collection efficiency of the HAFES (Eq. 1) was calculated using Eq. (3):

To calculate R (Eq. 2),

The size of the collected virus particles was measured with a transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEM-1011, JEOL, Japan) and compared with that of the aerosolized virus particles. A collection sample (4 μL) was placed on a TEM grid (3420C-CF, SPI Supplies, USA). After 30 s, materials other than the virus particles were wicked away using filter paper (01531055, ADVANTEC, USA). After this, 4 μL of 1% uranyl acetate (E22400-1, Science Services, Germany) was placed on the grid for 15 s, and filter paper was used to remove the reagent. Another 4 μL of ultra-pure water was used to wash away the residue. The negatively stained virus on the grid was observed after drying for 30 min at room temperature.

ATH sample preparation in a viral epidemic scenario

The virus sampling performance of the HAFES was compared with that of the SKC BioSampler for A/H1N1 and HCoV-229E, which were aerosolized and collected using the air samplers. According to Yang et al. (2011), the airborne virus concentration in indoor environments (a day-care center, health center, and airplane) during an IAV outbreak varies from 5.8 × 103 to 3.7 × 104 RNA genome copies/m3. Therefore, for A/H1N1 and HCoV-229E, a concentration of 3.57 × 104 RNA copies/m3 in the air was used in this study. The virus stocks were diluted with 50 mL of deionized water. The virus solution was then aerosolized using an atomizer with a 2 L/min flow of clean air. After passing through a diffusion dryer and a neutralizer, the airborne virus particles entered the HAFES and the SKC BioSampler. The HAFES was operated with an air flow rate of 100 L/min and an applied voltage of −10 kV. The air flow rate of the SKC BioSampler was 12.5 L/min. The virus particles collected via air sampling were employed in the real-time qRT-PCR analysis. Details of the protocol for real-time qRT-PCR assays are provided in Section 1 of Supplementary Information. The sampling time varied from 20 to 240 min

It was found that 99.0% and 99.7% of the RNA of A/H1N1 and HCoV-229E, respectively, were damaged during aerosolization with the atomizer. Therefore, a concentration of 3.57 × 106 RNA copies/m3 (100-fold higher than 3.57 × 104 RNA copies/m3) for A/H1N1 and 1.19 × 107 RNA copies/m3 (333-fold higher than 3.57 × 104 RNA copies/m3) for HCoV-229E were aerosolized with the atomizer. The measurement of the concentration (RNA copies/m3) of the aerosolized virus particles is described in detail in Section 2 of Supplementary Information.

Results and discussion

Virus collection efficiency

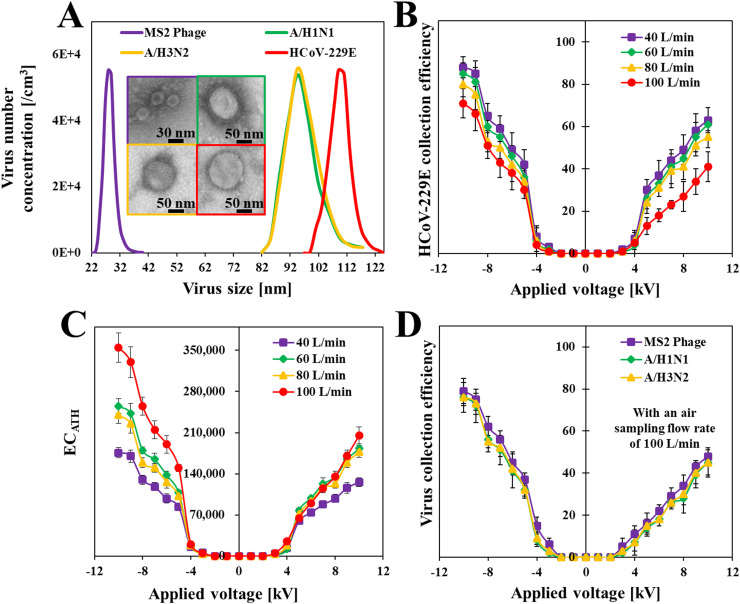

Fig. 3(A) presents SMPS data (measured right after the first DMA before entering the dilutor) for the airborne MS2, A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and HCoV-229E, which had peak diameters of 28, 95, 95, and 109 nm, respectively. The inset of Fig. 3(A) shows TEM images of the MS2, A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and HCoV-229E particles collected using the HAFES. The sizes of the collected virus particles were 29, 102, 100, and 115 nm, respectively, similar to the peak diameters and the sizes reported by previous studies (Taubenberger et al., 2005, Russell et al., 2008, Zhu et al., 2020, Merryman et al., 2019).

Characteristics of the aerosolized collection of virus particles using a high air flow-rate electrostatic sampler (HAFES). (A) Size distribution of the aerosolized virus particles and TEM images of virus particles collected using the HAFES. (B) Collection efficiency of the HAFES for human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E) under various air flow rates and applied voltages. (C) Aerosol-to-hydrosol enrichment capacity (

Fig. 3(B) presents the collection efficiency for aerosolized HCoV-229E under various air flow rates and applied voltages. The collection efficiency increased with the applied voltage for a given air flow rate and decreased with the air flow rate for a given voltage. Before testing with the virus aerosols, preliminary tests were conducted using NaCl. Section 3 of the Supplementary Information summarizes the electrical characteristics and aerosol (i.e., NaCl) size-dependent collection efficiency of the HAFES under various air flow rates and applied voltages. We selected an air flow rate of 100 L/min and an applied voltage of −10 kV (collection efficiency of 71 ± 7% for HCoV-229E) for subsequent virus sampling, even though the collection efficiency was 88 ± 5% with an air flow rate of 40 L/min and the same voltage (see Fig. 3(B)). The reason for this choice can be explained by the results for Fig. 3(C), which displays the

Fig. 3(D) presents the collection efficiency (

Enrichment capacity and recovery rate

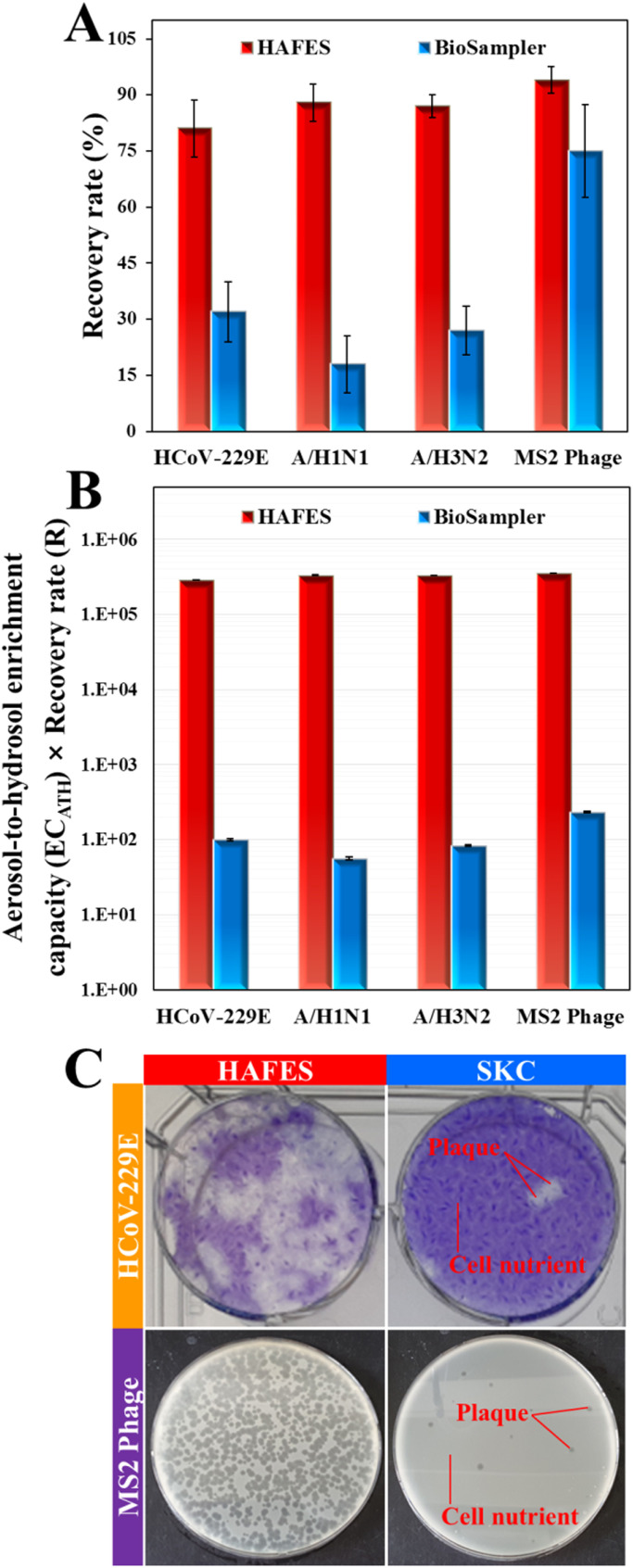

Fig. 4(A) presents the recovery data for HCoV-229E, A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and the MS2 bacteriophage that were collected using the HAFES and the SKC BioSampler. For HCoV-229E, the recovery rate using the HAFES (81%) was 2.7 times higher than that using the SKC BioSampler (32%). For A/H1N1 and A/H3N2, the recovery rates with the HAFES were 4.9 times (88%) and 3.2 times (87%) higher, respectively, than those with the SKC BioSampler (18% and 27%, respectively). For the MS2 bacteriophage, the HAFES produced a 1.25-times higher recovery rate (94%) than did the SKC BioSampler (75%). More detailed results are available in Section 4 of Supplementary Information (Table S1). The higher viral recovery rate for the HAFES could be because the velocity of the airborne particles in the collection medium using electrostatic sampling is about two to four orders of magnitude lower than when using inertial impaction sampling at comparable air flow rates (Kim et al., 2018, Mainelis, 1999), meaning that the HAFES was likely to be less destructive to the virus particles than was the SCK BioSampler. The ozone concentrations were measured using an ozone counter (OZ 2000G, SERES, France). The results were14 ± 3 ppb, 10 ± 2 ppb, and non-detectable at 0 cm, 3 cm, and 5 cm from the outlet of HAFES, respectively.

Comparison between the HAFES and the SKC BioSampler for non-destructive, high-speed virus collection. (A) Recovery rate (R) of the collected virus particles using the HAFES and the SKC BioSampler. (B) Aerosol-to-hydrosol enrichment capacity (

Fig. 4(A) also shows that the recovery rates were very similar (81–90%) for HCoV-229E, A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and the MS2 bacteriophage when the HAFES was employed. However, the SKC BioSampler exhibited much lower recovery rates for HCoV-229E (32%) and the influenza viruses (18% and 27% for H1N1 and H3N2, respectively) than for the MS2 bacteriophage (75%). It has been reported in a previous study that influenza viruses generally have a lower recovery rate than the MS2 bacteriophage when an inertia impaction air sampling method is used (Ge et al., 2014). When a large virus particle is captured by the collection media, it experiences a strong inertia force resulting in significant mechanical stress. Therefore, it is more likely that the coronavirus and influenza viruses will be damaged than the MS2 bacteriophage when the same air sampling speed is employed.

The recovery rate for the MS2 bacteriophage collected using the HAFES was compared with the recovery rates obtained using the batch-type EPC and a continuous-type electrostatic ATH sampler (ATHS) (Hong et al., 2016, Park et al., 2016). The recovery rate for the MS2 bacteriophage with the HAFES (94%) was higher than that with the ATHS (59%) and the EPC (55%). Further details are presented in Section 5 of Supplementary Information (Fig. S3(A)).

Fig. 4(B) presents the

Fig. 4(C) displays images of cultured viral plates of HCoV-229E and the MS2 bacteriophage collected using the HAFES and the SKC BioSampler. The numbers of viral plaques observed from the HAFES, for HCoV-229E and MS2 bacteriophage, were 10 times and over 100 times higher than those from the SKC Biosampler for HCoV-229E and MS2 bacteriophage, respectively.

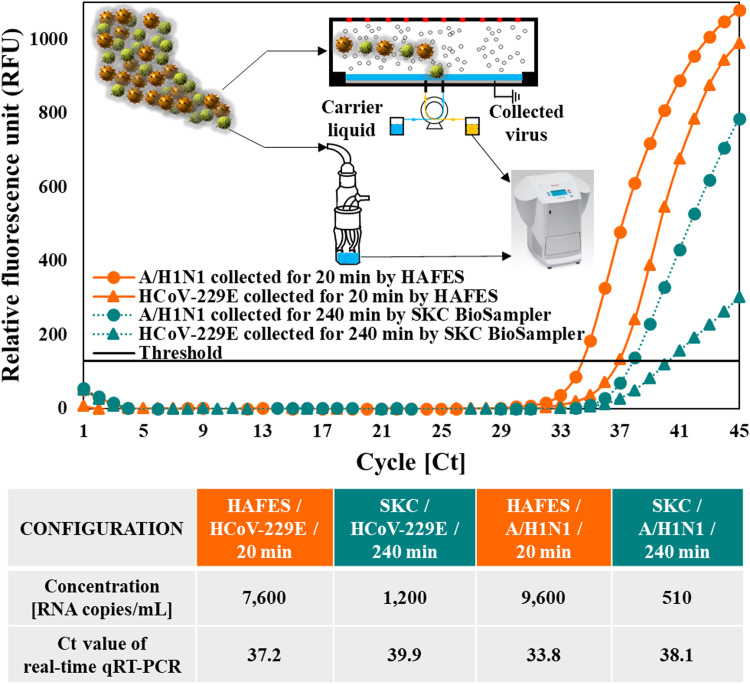

Detectable sample production in a simulated viral epidemic scenario

A/H1N1 and HCoV-229E particles at a concentration of 3.57 × 104 RNA copies/m3 were separately suspended in the air to simulate a viral epidemic scenario. Fig. 5 presents real-time qRT-PCR amplification curves for the virus samples collected using the HAFES and the SKC BioSampler and the corresponding concentrations and cycle threshold (Ct). The concentrations of the HCoV-229E and A/H1N1 samples collected over 20 min using the HAFES were 7,600 RNA copies/mL (Ct = 37.2) and 9,600 RNA copies/mL (Ct = 33.8), respectively. In contrast, the concentrations of the HCoV-229E and A/H1N1 samples collected using the SKC BioSampler were 1,200 RNA copies/mL (Ct = 39.9) and 510 RNA copies/mL (Ct = 38.1), respectively, for a collection time of 240 min. The HCoV-229E and A/H1N1 samples using the SKC BioSampler for a virus sampling time of under 240 min (i.e., 20, 60, 110, 160, and 200 min) were not detectable and not amplified by real-time qRT-PCR. On the other hand, Fig. 5 confirms that a sampling time of 20 min was sufficient to produce detectable samples for real-time qRT-PCR when using the HAFES in a viral epidemic scenario.

Real-time qRT-PCR assays for virus particles collected using an aerosol-to-hydrosol approach with the HAFES and the BioSampler in a viral epidemic scenario.

Conclusions

The HAFES was able to rapidly capture airborne viruses with a high collection efficiency even at a high air flow rate (71%, 79%, 76%, and 76% for HCoV-229E, the MS2 bacteriophage, A/H1N1, and A/H3N2, respectively, with an air flow rate of 100 L/min and an applied voltage of −10 kV). The HAFES produced high viral recovery rates for all viruses (81%, 94%, 88%, and 87% for HCoV-229E, the MS2 bacteriophage, A/H1N1, and A/H3N2, respectively, with an air flow rate of 100 L/min and an applied voltage of −10 kV). The ATH enrichment capacity (

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hyeong Rae Kim: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Sanggwon An: Investigation, Validation. Jungho Hwang: Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Technology Innovation Program-Industrial Technology Alchemist Project (20012215, Intelligent platform for in-situ virus detection and analysis) funded by the

High air flow-rate electrostatic sampler for the rapid monitoring of airborne coronavirus and influenza viruses

High air flow-rate electrostatic sampler for the rapid monitoring of airborne coronavirus and influenza viruses