- Altmetric

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Detoxification of quinones

- 3 The other side of the chemoprotection story – activation of quinones by NQO1

- 4 Are there endogenous quinone substrates for NQO1?

- 5 NQO1*2 polymorphism

- 6 Inducibility of NQO1 – Nrf2 and Ah receptor mediated induction

- 7 Catalytic functions of NQO1 in protection against oxidative stress

- 8 Other potential roles of NQO1 during oxidative stress

- 10 Implications of conformational changes in NQO1 on acetylation/deacetylation balance of microtubules

- 12 Relevance of NQO1 to disease states

- 13 NQO1 and aging

- 14 Summary

- Funding

- Declaration of competing interest

In this review, we summarize the multiple functions of NQO1, its established roles in redox processes and potential roles in redox control that are currently emerging. NQO1 has attracted interest due to its roles in cell defense and marked inducibility during cellular stress. Exogenous substrates for NQO1 include many xenobiotic quinones. Since NQO1 is highly expressed in many solid tumors, including via upregulation of Nrf2, the design of compounds activated by NQO1 and NQO1-targeted drug delivery have been active areas of research. Endogenous substrates have also been proposed and of relevance to redox stress are ubiquinone and vitamin E quinone, components of the plasma membrane redox system. Established roles for NQO1 include a superoxide reductase activity, NAD+ generation, interaction with proteins and their stabilization against proteasomal degradation, binding and regulation of mRNA translation and binding to microtubules including the mitotic spindles. We also summarize potential roles for NQO1 in regulation of glucose and insulin metabolism with relevance to diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, in Alzheimer's disease and in aging. The conformation and molecular interactions of NQO1 can be modulated by changes in the pyridine nucleotide redox balance suggesting that NQO1 may function as a redox-dependent molecular switch.

Introduction

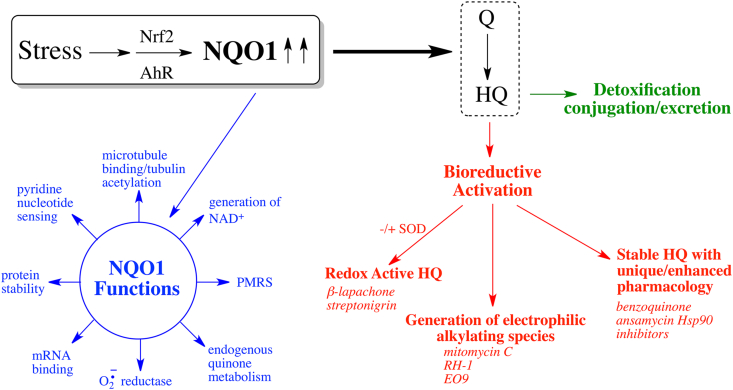

It has been more than sixty years since the discovery of DT-diaphorase now defined as NQO1 by Ernster and colleagues [1,2] and new roles for this enzyme are still being uncovered (see functions of NQO1 in Fig. 1). In this review, we will summarize the multiple functions of NQO1 but focus on the roles of NQO1 in redox processes that have been established and potential roles in redox control that are currently emerging. We will also highlight some disease areas where NQO1 has been shown to be protective and summarize literature regarding NQO1 in aging.

Induction of NQO1 and the role of NQO1 in quinone metabolism and defense against oxidative stress.

Subsequent to the discovery of DT-diaphorase (NQO1), its properties were more fully defined in the early 60's by Ernster and colleagues [[3], [4], [5]]. The enzyme had similarities to a protein investigated by Martius and colleagues as a vitamin K reductase [6,7] and as summarized in a historical perspective [8], these enzymes were probably identical.

Early work on NQO1 suggested it may play a role as a component of the electron transport chain but that was soon ruled out [3,9] Another early suggestion was that NQO1 played a role in vitamin K metabolism. While NQO1 efficiently reduces vitamin K3 or menadione and is inhibited by the anticoagulants warfarin and dicoumarol [6,10], more recent work has shown it is unlikely to play a major role in vitamin K metabolism with other enzyme systems catalyzing these reactions much more efficiently [11]. NQO1 knockout animals also do not have bleeding problems [12] and vitamin K protects against warfarin poisoning in both NQO1-deficient and wild type animals [13]. One of the significant and enduring early findings on NQO1 related to its inducibility by a wide variety of compounds and the ability of many of these compounds to protect against cancer [10,[14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]]. This led to the emergence of the role of NQO1 primarily as a chemoprotective enzyme but as work over the years has shown, there are significant exceptions particularly with respect to anticancer compounds [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24]].

Detoxification of quinones

One of the most cited roles for NQO1 is its protective effects against the deleterious oxidative and arylating effects of quinones and many of these studies utilized menadione (2-methyl-1,4-naphthoquinone) in cellular and other model systems [[25], [26], [27], [28], [29], [30]]. The mechanism of detoxification of quinones by NQO1 is based on the direct two electron mediated reduction of quinones to hydroquinones by NQO1 [31,32] removing electrophilic quinones and bypassing semiquinone radical and reactive oxygen species generation via redox cycling reactions. The crystal structure and mechanism of two electron reduction catalyzed by NQO1 has been clearly delineated by Amzel and colleagues [[33], [34], [35], [36]]. NQO1 has also been implicated in detoxification of benzene-derived quinones in bone marrow in a cell-specific manner [[37], [38], [39], [40]]. Consistent with this suggestion, the null NQO1*2 polymorphism which results in a lack of NQO1 protein (see Section 5) and an inability to detoxify quinones has been associated with increased toxicity in individuals occupationally exposed to benzene [[41], [42], [43]]. However, mechanisms underlying benzene toxicity are complex including the generation of a multiplicity of electrophilic metabolites and have recently been summarized in an IARC monograph [44].

The other side of the chemoprotection story – activation of quinones by NQO1

Hydroquinone generation is not always a detoxification step depending on the ability of hydroquinone to redox cycle, to rearrange to generate reactive electrophiles and the ability of the specific biological system to eliminate the hydroquinone either before or after conjugation via glucuronidation or sulfation [20,45,46]. Even in the well-cited case of menadione, small changes in the structure of the naphthoquinone alter the stability of the hydroquinone generated and can modulate toxicity [47,48]. 2-Hydroxy and 2-amino 1,4-naphthoquinone derivatives can be activated by NQO1 but interestingly in-vivo, not only the extent of toxicity could be modified by minor changes in structure relative to menadione but also the target site [[49], [50], [51]]. Superoxide dismutase (SOD) can also influence the autoxidation rates of hydroquinones generated by NQO1 and can either inhibit or accelerate autoxidation dependent on the stability and redox chemistry of the hydroquinone [45]. Activation of quinones via bioreductive mechanisms is a well-known approach in anticancer drug design [46,[52], [53], [54]] and NQO1-catalyzed generation of reactive hydroquinones derived from compounds as diverse as mitomycin C [22], E09 [55,56], aziridinylbenzoquinones [23,57,58], streptonigrin [54], β-lapachone [59], deoxynyboquinone [60] and geldanamycin based Hsp90 inhibitors [24] have been utilized as an approach to kill tumor cells with high levels of NQO1 which includes many solid tumors [61,62]. The mechanisms underlying tumor cell killing vary depending on the hydroquinone generated but the production of electrophilic intermediates that arylate DNA (mitomycin C, aziridnylbenzoquinones), reactive oxygen species (β-lapachone, streptonigrin, deoxynyboquinone) or molecules that are more efficient at inhibiting the specific cellular target (Hsp90) have all been demonstrated (Fig. 1).

NQO1 targeted drug delivery

The efficient reduction of quinones by NQO1 to chemically reactive hydroquinones has been utilized in a number of innovative studies designed to target drug delivery to NQO1 rich tumors. Numerous quinone conjugates have been developed where following hydroquinone formation, the compound undergoes chemical rearrangement triggering the release of a cytotoxic molecule that is separate from the quinone component [[63], [64], [65], [66], [67], [68], [69], [70]]. Similarly, the quinone/hydroquinone trigger has been used to catalyze the release of fluorescent dyes into NQO1-rich tumors as a mechanism to distinguish tumor cells from normal cells [[71], [72], [73], [74]]. The NQO1-dependent quinone/hydroquinone trigger has also been employed to catalyze the release of encapsulated cargo from a carrier complex (liposome, nanoparticle) into tumor cells [[75], [76], [77]]. In these models, the quinone component of the carrier molecule undergoes reduction to a hydroquinone by NQO1 which results in either chemical modification or degradation of the carrier allowing for release of the encapsulated drug into the tumor. A highly novel method of self-triggered cascading amplification drug delivery to NQO1-rich cells has also been developed [78]. In this system, β-lapachone and doxorubicin are encapsulated in an oxygen sensitive carrier. Following uptake into the tumor, leakage of small amounts of β-lapachone or endogenous reactive oxygen species initiate the degradation of the oxygen sensitive carrier. This initial degradation induces the release of more β-lapachone from the carrier and increases the generation of ROS which further stimulates the degradation of the carrier and release of doxorubicin [78].

Are there endogenous quinone substrates for NQO1?

There are many examples of xenobiotic quinones and other exogenous compounds that are metabolized by NQO1 [8,10,79]. Endogenous quinones that are metabolized by NQO1 constitute a much smaller list. Early suggestions included vitamin K (above) but we will discuss other possibilities below.

Ubiquinone and CoQ derivatives

In an important observation for the potential role of NQO1 in oxidative stress, NQO1 was shown to reduce CoQ substrates with various chain lengths to their antioxidant hydroquinone forms [80]. Long chain derivatives of CoQ were approximately two orders of magnitude slower substrates for purified NQO1 as their shorter chain analogs but NQO1 was still able to efficiently reduce long chain ubiquinone derivatives (CoQ9 and CoQ10) that had been pre-incorporated into both artificial and natural membrane systems. Essentially all of the CoQ9 or CoQ10 pre-incorporated into lipid vesicles could be reduced to their quinol derivatives by the addition of NQO1 and NADH, a reaction inhibited by the NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol. These observations were consistent with early work on NQO1 which showed activation of enzyme activity by lipids and the requirement of non-ionic detergents in assay systems for NQO1 for maximal activity [10] and provided support for a CoQ reductase role for NQO1. In lipid vesicles, CoQ10, NQO1 and NADH protected against lipid peroxidation and similarly CoQ10 prevented lipid peroxidation in isolated rat hepatocytes in reactions inhibited by the NQO1 inhibitor dicoumarol [80,81].

Vitamin E quinone

NQO1 can play a role in regenerating antioxidant forms of α-tocopherol (vitamin E) after free radical attack. Oxidation of α-tocopherol by hydroperoxyl radicals generates a tocopherone derivative which can either hydrolyze to α-tocopherol quinone (TQ) or can be reduced to regenerate α-tocopherol [82]. Recombinant NQO1 could reduce TQ, which is devoid of antioxidant protection, to α-tocopherol hydroquinone (THQ) which is an effective antioxidant [83] thus preserving antioxidant capacity. Cells stably transfected with human NQO1 exhibited greater reduction of TQ to THQ and greater protection against cumene hydroperoxide induced lipid peroxidation [83]. A role for NQO1 in regenerating α-tocopherol directly from its tocopherone derivative has been proposed [84] and the conversion of orally administered TQ to α-tocopherol has been verified in humans [85]. Although the enzyme systems responsible in conversion were not defined, a mechanism was proposed involving hydrolysis of THQ to α-tocopherol [85].

Catechol estrogen o-quinones

Metabolism of o-quinones derived from the endogenous estrogens estrone and estradiol by NQO1 has toxicological significance since the quinones are known to form depurinating adducts in DNA which have been suggested to contribute to the carcinogenic activity of estrogens [86,87]. However, there are conflicting reports of the ability of quinones derived from the oxidative metabolism of the estrogens estrone and estradiol to serve as substrates for NQO1. NQO1 has been reported to metabolize estrogen derived o-quinones [88] but the role of NQO1 in the detoxification of 4-hydroxyestrone o-quinone has been questioned [89] due to its relatively poor ability to undergo NQO1-mediated catalysis [90,91]. Estrogen derived ortho-quinones are also known to be better substrates for NQO2 than NQO1 [92]. Although estrogen derived o-quinones are relatively poor substrates for NQO1, expression of polymorphic variants of NQO1 (R139W and P187S) with diminished stability and metabolic capability resulted in increased estrogen DNA adducts in human mammary epithelial cells [93]. There is evidence that DNA adduct generation after treatment of human mammary epithelial cells with either estradiol or its oxidative metabolite 4-hydroxyestradiol was reduced by both pharmacological (sulforaphane) and genetic (siRNA for Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1; Keap1) approaches to activate NF-E2 p45-related protein 2 (Nrf2) [94]. Although this finding is consistent with NQO1 mediated detoxification of estrogen-derived quinones limiting DNA adduct formation, results could also be explained via other Nrf2 upregulated systems or Nrf2 independent mechanisms [94]. Interestingly, antiestrogens have also been found to upregulate NQO1 via transcriptional mechanisms modulated at the level of the estrogen receptor resulting in decreased oxidative DNA damage in breast cancer cells [95,96].

Dopamine derived quinones

The metabolism of dopamine to neuromelanin is complex and involves a number of steps where quinoid metabolites can be generated [[97], [98], [99], [100]]. The tyrosinase mediated generation of dopamine ortho-quinone is followed by cyclization at physiological pH to leukaminochrome, oxidation to the cyclized quinone aminochrome and eventual polymerization to melanins. Both NQO1 and NQO2 can metabolize dopamine derived ortho quinones [99,101,102]. Extensive work by Segura-Aguilar and colleagues have suggested a role for aminochrome in degeneration of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta in Parkinson's Disease and a protective role of NQO1 (for recent review see Ref. [100]). Aminochrome is a substrate for NQO1 [101] and despite generating a redox labile hydroquinone [99,101,102], NQO1 protects against many of the toxic effects induced by aminochrome. In dopaminergic cells, NQO1 has been found to be protective against aminochrome induced adverse effects including mitochondrial damage and ER stress [103], alpha synuclein oligomer formation [104], proteasomal dysfunction [99], lysosome dysfunction [105], microtubule and cytoskeletal damage [106,107] and autophagy [108]. NQO1 also protects dopaminergic cells against dopamine [109] and aminochrome induced cell death [110]. In-vivo, aminochrome was toxic to dopaminergic neurons located in the substantia nigra after intra-striatal injection into the brain but only after NQO1 was suppressed [111]. Since NQO1 has been found in rat substantia nigra [112] and in humans, in normal and Parkinsonian substantia nigra [113], it may play an endogenous detoxification role against dopamine-derived quinones in general and aminochrome in particular.

NQO1*2 polymorphism

The NQO1*2 polymorphism (rs1800566) is the result of a C to T base pair change at position 609 (cDNA) resulting in a proline to serine amino acid substitution at position 187 of the protein [114,115]. The mutant NQO1*2 protein has markedly decreased stability, FAD binding ability and a dramatically reduced half-life due to rapid polyubiquitination and proteasomal degradation [116,117]. The resultant phenotype of the NQO1*2 polymorphism is the near complete absence of a functional protein in individuals homozygous for the mutant allele while reduced levels of functional protein are seen in heterozygous individuals [117,118].

The mutant NQO1*2 protein has been thoroughly studied with respect to conformational dynamics and mobility. The substitution of the conformationally restricted proline 187 not only leads to local increased mobility close to the monomer interface but has destabilizing effects at distal sites including the FAD binding site in the N terminal domain and the C terminal regions [[119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126]]. Small molecules such as riboflavin and dicumarol have been shown to stabilize the NQO1*2 protein and prevent proteasomal degradation [123].

The frequency of NQO1*2 allele demonstrates wide ethnic diversity ranging from 0.18 in European populations to as high as 0.61 in the Hmong population of southeast Asia [[127], [128], [129]]. Over 100 studies have examined the association of the NQO1*2 allele either alone or in combination with other mutant alleles in human diseases. Recently, more in depth meta-analysis have been performed and the results from these studies suggests that the variant allele is associated with an increased risk of cancer in hepatocellular carcinoma as well as colorectal [[130], [131], [132]]; bladder [133,134]; and gastric [132,134,135] cancers.

Inducibility of NQO1 – Nrf2 and Ah receptor mediated induction

NQO1 is induced as a part of the Nrf2-directed adaptive response to cellular stress including electrophilic and oxidative stress and also activated as a component of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) directed response (Fig. 1), for reviews see Refs. [20,136]. In addition to Nrf2 and AhR mediated induction of NQO1, the methylation status of the NQO1 promoter may also be an important factor controlling NQO1 expression [[137], [138], [139], [140]]. Mechanisms have also been proposed for the transcriptional regulation of NQO1 by antiestrogen-liganded estrogen receptor [95,96].

One aspect of NQO1 induction that has been recently exploited is the activation of antitumor compounds by NQO1 in tumors that have aberrant and persistent Nrf2 upregulation as a result of activating mutations in the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway and other mechanisms [141]. Nrf2 is activated in many tumor types and such tumors often exhibit resistance to existing therapies resulting in poor patient outcomes [141]. This has led to the development of Keap1 knockout cell line screens for the identification of compounds that exhibit synthetic lethality with Nrf2 overexpression [142,143]. Compounds such as mitomycin C and quinone based Hsp90 inhibitors which are activated by NQO1 have been identified in screens for agents that induce selective toxicity to tumors with activated Nrf2 [142,143]. Nrf2 activation would increase tumor NQO1 levels leading to activation of either mitomycin C to reactive quinone methide metabolites capable of alkylating DNA and the generation of hydroquinone derivatives of geldanamycin quinones which are more active Hsp90 inhibitors [22,24]. It would be interesting to determine the selectivity profile of other NQO1-activated antitumor compounds in tumors with active Nrf2. β-Lapachone would be an interesting prospect given the innovative combination therapies developed by Boothman and colleagues with PARP inhibitors and with ionizing radiation [[144], [145], [146]]. However, additional molecules such as the aurora kinase inhibitor AT9283 have also been identified in these screens for selective killing of tumor cells with elevated Nrf2 levels [147] which do not have obvious links to NQO1-mediated bioreductive activation, although NQO1 has been reported to bind directly to aurora A [148]. A more complete analysis of compounds activated in cells with activated Nrf2 is detailed in the original references [142,143,147] and in a comprehensive recent review by Hayes and colleagues [141].

One of the common questions that arises is why is NQO1 so commonly activated as a component of the Nrf2 and Ah receptor induction systems in stress conditions and particularly in oxidative stress. In this short review, we will summarize the potential roles of NQO1 in protection against oxidative stress that have been described [20,79,84,[149], [150], [151]] and discuss other aspects of NQO1 biochemistry and function that are emerging which may indicate a role of NQO1 as a redox signaling system.

Catalytic functions of NQO1 in protection against oxidative stress

Generation of reduced CoQ9 and CoQ10 via NQO1 mediated reduction

The generation of hydroquinone forms of long chain CoQ derivatives CoQ9 and CoQ10 by NQO1 incorporated into lipid membranes and resultant protection from lipid peroxidation [80] was discussed in section 4.1. These authors suggested that NQO1 was selected during evolution as an endogenous CoQ reductase to maintain antioxidant protection [80].

Vitamin E quinone

Conversion of TQ to its antioxidant THQ by NQO1 was demonstrated using purified NQO1 and in cellular systems where it also provided antioxidant protection against lipid peroxidation [83]. Vitamin E quinone was discussed as a potential endogenous substrate for NQO1 in section 4.2.

The plasma membrane redox system (PMRS) system

Redox functions in the plasma membrane have been recognized for more than 75 years [152] and were extended to mitochondrial membrane redox systems with the concept of direct coupling of redox energy and ion transport (see Ref. [153] for a comprehensive review). The plasma membrane redox system (PMRS) is an important antioxidant system in cells and consists in its most basic form of antioxidants, enzymatic and chemical reductants and a source of reducing equivalents most commonly NAD(P)H [154]. Membrane antioxidant systems are complex but a useful schematic of the interrelationship of its components can be found in Ref. [155]. These components include CoQ10, α-tocopherol, ascorbate and a number of reducing enzymes capable of maintaining antioxidant forms of α-tocopherol and CoQ10. NADH-cytochrome b5 reductase can reduce CoQ via a one electron mechanism while as discussed above, NQO1 can reduce CoQ10 in lipid environments via a two-electron mechanism directly to ubiquinol. Other reductases capable of reducing CoQ have also been described [[156], [157], [158], [159]]. Ubiquinol can also contribute to regeneration of α-tocopherol from the α-tocopherol radical [159] and mechanisms have also been proposed for the regeneration of α-tocopherol by ascorbate [160]. Enzymatic reductases are critical to the PMRS and NQO1 plays an important function in generating reduced forms of CoQ10 and TQ and protecting against lipid peroxidation as described in sections 4.1, 4.2 [80,83,161].

Superoxide reductase activity

In biochemical experiments carried out to study oxidation and reduction reactions of free-flavins in solution, the addition of superoxide dismutase (SOD) prevented the oxidation of reduced flavin, suggesting that superoxide was responsible for the observed flavin oxidation [162,163]. Since the active site of NQO1 contains non-covalently bound flavin in the form of FAD and can generate and maintain reduced flavin (as FADH2) via the oxidation of NAD(P)H, whether NQO1 could function as a NAD(P)H-dependent superoxide reductase was examined. Experiments using purified recombinant NQO1, and in cellular systems expressing NQO1, confirmed that NQO1 does possess superoxide reductase activity [164,165]. Kinetic studies, however, have shown that the rate of superoxide reduction by NQO1 was orders of magnitude slower than the rate reported for superoxide detoxification by SOD, suggesting a limited role for NQO1 in protection against superoxide [164]. However, the high levels of NQO1 found in many cell types either before or after induction via stress responses may help compensate for the slower rate of reduction of superoxide by NQO1. High levels of NQO1 protein expression have been detected in tissues from areas of the body with exposure to high levels of oxygen such as the cornea and lens of the eye [166,167], respiratory tract and blood vessels [167,168] and in cells sensitive to oxygen exposure including adipocytes where NQO1 may offer added protection against lipid peroxidation [167,169,170]. High levels of NQO1 can also be found in many types of cancers and may provide additional protection against oxidative damage [167,171].

Other potential roles of NQO1 during oxidative stress

Stabilization of target proteins against proteasomal degradation

One of the more intriguing features of NQO1 is its ability to bind to and protect a wide range of target proteins from proteasomal degradation. A growing list of proteins which have been shown to be protected against proteasomal degradation by NQO1 are shown in Table 1. For many of these proteins the protection afforded by NQO1 was shown to be NAD(P)H-dependent. In cell-free studies using purified proteins and mass spectrometry the NQO1 homodimer was shown to bind directly to the 20S proteasome [124]. In these studies, the association of NQO1 with the 20S proteasome was similar in the presence and absence of NADH suggesting that the interaction of NQO1 with the 20S proteasome, in contrast to interactions with target proteins, did not depend on the pyridine nucleotide redox balance.

The ability of NQO1 to stabilize the viral HIV protein TAT and hepatitis B virus X protein (HBx) implicates NQO1 as a potential factor in viral replication. In cell studies the NQO1 inhibitor dicumarol was shown to reduce HIV viral replication by increasing proteasomal degradation of TAT which is required for the efficient transcription of HIV encoded genes. In a proposed feedback-loop one of these HIV genes encodes for the protein Rev, which was shown to down-regulate the expression of NQO1, resulting in increased TAT degradation. In this system, the authors describe NQO1 as a host protein which modulates the actions of two opposing HIV regulatory proteins [172]. Dicumarol also demonstrated antiviral activity against hepatitis B virus infection in hepatocytes and in animals. Treatment with dicumarol or NQO1 knock-down resulted in a decrease in amount of viral covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA) by increasing the degradation of HBx, a viral protein required for cccDNA transcription [173].

β-Lapachone and the generation of NAD+

Redox cycling quinones such as β-lapachone have potent anti-tumor activities due to their ability to generate reactive oxygen species and oxidative DNA damage [174]. Experiments have shown that NQO1 is the primary reductase responsible for the anti-tumor activity of β-lapachone [175]. NQO1 catalyzes the reduction of β-lapachone to an unstable hydroquinone which rapidly auto-oxidizes generating high levels of reactive oxygen species while at the same time also generating large amounts of NADP+ and NAD+ via the oxidation of NAD(P)H [175]. In experiments with β-lapachone, rapid NAD(P)H oxidation was observed but without a corresponding increase in NAD+. The addition of PARP inhibitors restored NAD+ levels indicating that PARP was responsible for the consumption of NAD+ which was consistent with oxidative DNA damage induced by β-lapachone followed by PARP-mediated DNA repair [144,176,177]. NQO1-mediated futile redox cycling of β-lapachone leads to oxidative DNA damage, hyperactivation of PARP, depletion of NAD+ and ATP and a specific type of programmed necrosis termed NAD+-keresis [146,[178], [179], [180]]. These experiments exposed opposing roles for NQO1 in β-lapachone induced cytotoxicity where the enzyme is responsible for the generation of reactive metabolites, but at the same time produces NAD+ to aid in DNA repair. To avoid oxidative DNA damage while retaining the ability to increase the NAD+:NADH ratio, the use of low-dose β-lapachone has been examined for the treatment of a wide-range of disorders. In these studies with low dose β-lapachone, the generation of NAD+ by NQO1 to enhance PARP and sirtuin-catalyzed reactions has been proposed in part to explain the therapeutic benefits observed [176,[181], [182], [183]].

Association of NQO1 with microtubules

The first reported association of NQO1 with microtubules came from studies using Xenopus egg extracts where experiments with inhibitors and immunodepletion showed that inhibition or loss of NQO1 resulted in a decrease in microtubule mitotic structures [184]. Later it was shown using immunostaining for NQO1 in cultured cells and archival tissues that NQO1 co-localized with α-tubulin to the centromere, mitotic spindles and midbody [177,185]. These microtubule structures contain high levels of acetylated α-tubulin (K40) and NQO1 was shown to co-localize with these acetylated structures in double-immunostaining studies [177]. Binding of NQO1 dimer to microtubules likely occurs via its positively charged C-terminal tails which are exposed when the enzyme is in the oxidized state [177,186]. A number of NAD+-dependent enzymes including SIRT2 and PARP have also been observed to co-localize with these acetylated microtubule structures suggesting that NQO1 may be providing NAD+ for these enzymes [[187], [188], [189]]. More recently it was demonstrated that mitotic progression was delayed when NQO1 was compromised [190]. In these studies, NQO1 and SIRT2 were shown to be bound together and co-localized to the mitotic spindle where it was proposed that NQO1 functions as a downstream modulator of SIRT2 deacetylase activity through its ability to bind to SIRT2 and provide NAD+ [190].

We had previously suggested that binding of oxidized NQO1 to acetylated microtubules could act as a mechanism to retain the enzyme near microtubules where NQO1 could provide antioxidant protection [177]. Given more recent findings, it also seems probable that NQO1 localization on microtubules provides a mechanism to regulate the microtubule acetylome and acetylation/deacetylation balance (see Sec 10).

NQO1 as a molecular switch responding to pyridine nucleotide redox ratios

The flavoproteome consists of approximately 100 proteins and mutations in a surprisingly large proportion of flavoproteins (approximately 60%) are associated with human disease [191]. A role for flavin containing enzymes as cellular redox switches is well known and Becker et al. [192] have highlighted how the flavin redox state can mediate protein interactions with other proteins and macromolecules playing a role in transcriptional regulation, changes in localization, membrane binding and cell signaling. Conversion of the flavin from an oxidized to a reduced state or vice versa triggers a conformational change and functional output. Hydrogen bond networks linking the flavin to the surface of the protein are often found in these proteins [192]. Proteins highlighted by Becker et al. [192] included the fungal Vivid light sensor protein [193] and the transcriptional regulators of bacterial proline utilization A protein (PutA) [194,195] and nitrogen fixation (NifL) [196]. In addition, E. coli pyruvate oxidase switches from a cytosolic to a membrane bound protein after flavin reduction and release of the C terminal tail to allow the enzyme to efficiently catalyze ubiquinone reduction in the membrane [192,197,198].

Mammalian NQO2 has been proposed as a flavin redox switch with changes in FAD orientation on reduction in the presence of primaquine and chloroquine [199,200]. Reduced NQO2 has structural and electrostatic properties that result in preferential binding of certain DNA intercalating agents [201], thus demonstrating a separate pharmacological profile to the oxidized form of the enzyme.

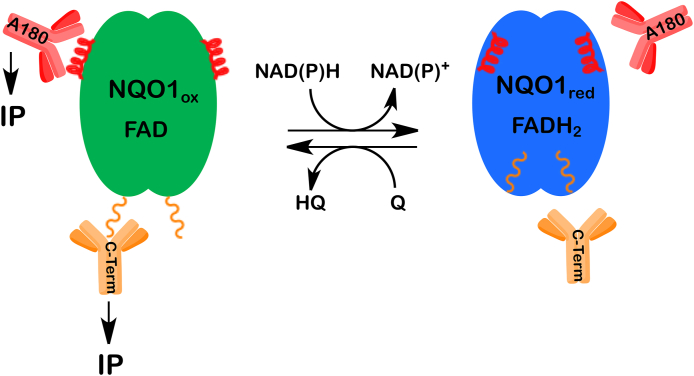

Our own work has shown that NQO1 may also function as a redox sensing protein and redox switch. Local pyridine nucleotide ratios result in FAD reduction and altered conformation of the protein. The change in conformation results in loss of binding to antibodies that target multiple sites on NQO1 [177]. This conformational change is reversible depending on the levels of reduced pyridine nucleotides and flavin redox state. In many cases, protection against proteasome-mediated degradation of proteins by NQO1 (see above) was dependent upon pyridine nucleotide levels suggesting that the interaction of NQO1 with target proteins may be influenced directly by the NAD(P)H:NAD(P)+ ratio and protein conformation. This has led us to consider the role of NQO1 as a potential reduced pyridine nucleotide redox sensor that can respond to changes in the pyridine nucleotide redox environment by altering its conformation.

Biochemistry of the NQO1 redox switch

NAD(P)H was found to protect NQO1 against proteolytic digestion suggesting the protein underwent a protective conformational change in structure [202]. Under normal conditions where NAD(P)H levels are plentiful, NQO1 adopts a reduced conformation following hydride transfer from NAD(P)H to the FAD co-factor in NQO1. In the presence of efficient electron acceptors such as certain quinones, the reduced form of the flavin has a very short lifetime [[203], [204], [205]]. However, in the absence of efficient electron acceptors. there was only a slow rate of reaction between O2 and reduced flavin [206] showing that the reduced form of the enzyme has appreciable stability under these conditions. X-ray crystallography, biochemical and computational studies performed by Amzel, and colleagues suggested that the stability of the reduced form of NQO1 occurred in part as a result of stabilization of charge separation in the reduced flavin by the protein [207,208]. The reduced and oxidized forms of NQO1 can be distinguished by using redox-dependent antibodies that bind to oxidized but not reduced NQO1 [177]. NQO1 undergoes a conformational change upon binding of reduced pyridine nucleotides, resulting in loss of immunoreactivity to antibodies that bind to helix 7 of the catalytic core domain or the C-terminus [177]. In the presence of NAD(P)H but in the absence of an efficient quinone electron acceptor, very little NQO1 could be immunoprecipitated demonstrating the presence of the reduced form of NQO1. As NAD(P)H levels are depleted, NQO1 can no longer maintain a reduced conformation and the protein reverts to its oxidized form enabling immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2). The distinct reduced and oxidized conformations of NQO1 have not been structurally characterized but non-denaturing gels clearly show different migratory properties for the reduced and oxidized conformations of the enzyme [177]. In subsequent studies [186], it was demonstrated that NQO1 can exist in at least three different conformational forms, a reduced conformation, an oxidized conformation and an inactivated conformation which have different reactivities with antibodies and therefore different implications for reacting with downstream proteins.

Schematic representation of the redox-dependent immunoreactivity of NQO1. When NAD(P)H is readily available NQO1 adopts the reduced conformation (blue) preventing antibodies from binding to redox-dependent epitopes within helix 7 (A180) and to the C-terminal tails. When NAD(P)H levels drop the enzyme cannot maintain the reduced conformation and the redox-dependent epitopes are exposed allowing for immunoprecipitation. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Implications of conformational changes in NQO1 on acetylation/deacetylation balance of microtubules

Acetylation and deacetylation of microtubules is a dynamic process and post translational modifications including acetylation balance at α-tubulin K40 have been suggested to affect microtubule stability and flexibility in turn minimizing microtubule aging and optimizing resilience [[209], [210], [211], [212], [213]]. Acetyl α-tubulin K40 is unique since it is the only lysine residue in the internal lumen of the microtubule. HDAC6 regulates the majority of microtubule deacetylation at K40 but SIRT2 also plays a significant K40 deacetylation role in the perinuclear region of the cell [214]. High intensity immunostaining for NQO1 in cells was reflective of an oxidized pyridine nucleotide environment in cells immunostaining and proximity ligation assays showed co-localization of NQO1 with acetylated microtubules and SIRT2 [177]. SIRT2 and NQO1 have also been found to co-immunoprecipitate [190]. The close proximity of NQO1, SIRT2 and acetyl K40 on microtubules led us to investigate the hypothesis that NQO1 may generate NAD+ near microtubules to facilitate SIRT2 mediated deacetylation.

We initially utilized β-lapachone, which is an excellent substrate for NQO1 causing the generation of the oxidized form of NQO1, catalytic oxidation of NAD(P)H, the production of hydrogen peroxide and subsequent DNA damage and rapid NAD+ depletion via PARP mediated DNA repair. In cells treated with β-lapachone a marked increase in the level of oxidized NQO1 was detected following immunoprecipitation with redox reactive anti-NQO1 antibodies concomitant with generation of the oxidized form of NQO1 [177]. This was consistent with the observation of high intensity cellular immunostaining for NQO1 under conditions where reduced pyridine nucleotide levels were decreased and the oxidized form of NQO1 was generated [177].

Oxidized and reduced NQO1 have different conformations but the addition of NQO1 inhibitors (dicoumarol or indolequinone mechanism based inhibitors) also induced a change in the conformation of NQO1 [177,186]. siRNA-mediated knockdown or CRISPR/Cas9 knockout of NQO1 in 16-HBE human lung epithelial cells or 3T3L1 mouse fibroblasts had little effect on acetyl α-tubulin K40 levels suggesting NQO1 was not providing NAD+ for SIRT2 mediated deacetylation in this system. Altering the conformation of NQO1 using an indolequinone mechanism-based inhibitor, however, resulted in decreased binding of NQO1 to microtubules and, as observed when the oxidized conformation of NQO1 was generated intracellularly, an increase in the levels of acetyl α-tubulin K40 [186]. No changes in the cellular levels of reduced and oxidized pyridine nucleotides were detected as a result of treatment of cells with the indolequinone inhibitor of NQO1 suggesting the change in acetyl α-tubulin K40 levels was dependent on the conformational change in NQO1 and decreased microtubule binding [186]. Our interpretation of these results was that altered conformations of NQO1 regulate its binding to microtubules and disrupt the crowded protein environment in the lumen and the microtubule acetylome resulting in either increased acetylation or decreased deacetylation of α-tubulin K40 (Fig. 3).

![Redox-dependent binding of NQO1 to microtubules. NAD(P)H levels direct the conformation of NQO1 and binding to microtubules. Inactivation of NQO1 by the inhibitor MI2321 alters the conformation of NQO1 preventing it from binding to microtubules disrupting the balance of acetylation/deacetylation (α-tubulin, K40) in the lumen of the microtubule leading to increased α-tubulin acetylation. Figure has been modified from Ref. [186].](/dataresources/secured/content-1766004488001-74cb0866-a1cf-4f04-9350-97025a2d2750/assets/gr3.jpg)

Redox-dependent binding of NQO1 to microtubules. NAD(P)H levels direct the conformation of NQO1 and binding to microtubules. Inactivation of NQO1 by the inhibitor MI2321 alters the conformation of NQO1 preventing it from binding to microtubules disrupting the balance of acetylation/deacetylation (α-tubulin, K40) in the lumen of the microtubule leading to increased α-tubulin acetylation. Figure has been modified from Ref. [186].

NQO1 may modulate acetylation levels in cells via a number of mechanisms. The notion that NQO1 can generate NAD+ during catalysis to provide NAD+ for SIRT mediated deacetylation has been supported by a number of studies [183,190,215,216]. We did not find evidence for this mechanism in the cellular model systems that we used; however, we found that NQO1 conformation, which is primarily regulated by the redox environment, can result in modulation of acetyl α-tubulin K40 levels and microtubule structure. Therefore, in addition to providing NAD+, NQO1 may also respond to the local pyridine nucleotide redox environment surrounding SIRT2 rich regions of microtubules and modulate the acetylation/deacetylation balance via conformation-dependent protein interactions.

Overall, this emphasizes the redox and conformational-dependent changes in NQO1 structure and how it may play an alternative redox sensing and/or redox-switching role. Changes in pyridine nucleotide redox status would result in altered NQO1 conformation which in turn could modulate downstream NQO1 interactions. Whether conformational changes in NQO1 result in altered location of the protein is intriguing and needs to be further investigated. NQO1 is known to be primarily cytosolic but has been reported to have significant nuclear, mitochondrial and membrane pools in different cell types [3,9,[217], [218], [219]].

Role for NQO1 in the regulation of mRNA translation

In experiments with proliferating HeLa cells, UV crosslinking was used to aid in the capture and characterization of novel mRNA binding proteins. Results from this study identified more than 800 mRNA binding proteins, one of which was NQO1 [220]. The binding of NQO1 to mRNA was hypothesized to occur via the di-nucleotide binding (Rossmann) fold [220]. The NQO1 active site contains a modified Rossmann fold where the third α/β pair is either missing or included in the crossover section located between two sections of the parallel β-sheet [221]. Since the active site of NQO1 undergoes a conformational change upon binding of NAD(P)H and transfer of the hydride to FAD it is reasonable to assume that the binding of NQO1 to mRNA could be regulated by the redox state of NQO1. Di Francesco et al., using ribonucleoprotein immunoprecipitation and microarray analysis identified a subset of NQO1 target mRNA's in human hepatoma HepG2 cells [222]. One of these mRNA targets was identified as SERPINA1 mRNA which encodes for the serine protease inhibitor α-1-antitrypsin (A1AT). Biotin pulldown experiments demonstrated that NQO1 can bind to both the 3′ untranslated region as well as the coding region of SERPINA1 mRNA. These studies also showed that NQO1 did not affect the levels of SERPINA1 mRNA, but instead, NQO1 binding enhanced the translation of SERPINA1 mRNA [222]. In another study, NQO1 was found to associate with polysomes isolated from mouse muscle tissue and in these experiments using co-immunoprecipitation NQO1 was shown to bind to the 60S ribosomal protein L13A [223]. The ability of NQO1 to bind to both mRNA transcripts and the 60S ribosome suggests that NQO1 may play multiple roles in mRNA translation.

Relevance of NQO1 to disease states

Oxidative stress is relevant to many disease states but we will focus on the potential roles of NQO1 in glucose and insulin response with relevance to type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome and in Alzheimer's disease.

Nrf2 and NQO1 in glucose and insulin response

The Keap1-Nrf2 pathway is a potential target for the prevention of type 2 diabetes, obesity and metabolic syndrome [224]. Activation of Nrf2 in multiple murine diabetes models has led to improvements in insulin resistance [225]. Multiple biological mechanisms and pathways are likely responsible for the effects of Nrf2 including protection from oxidative stress, repression of hepatic gluconeogenesis, effects on lipid synthesis, mitochondrial function, inflammation, glycogen metabolism and crosstalk with other signaling systems [[224], [225], [226], [227], [228], [229]]. A Nrf2 inducer reversed insulin resistance in obese mice, suppressed hepatic steatosis and reduced NASH and liver fibrosis via inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum, inflammatory and oxidative stress [230] However, these are complex diseases and there is conflicting experimental data regarding the effects of Nrf2 on insulin sensitivity, adipogenesis, inflammation and obesity [231,232] in part because of the multiplicity of Nrf2 mediated actions and context-dependent effects. A recent review focusing on redox biomarkers in obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes summarized conflicting data on the influence of Nrf2 in regulating obesity and metabolic health in response to HFD [233].

Interestingly, the downstream target of Nrf2, NQO1, has also been implicated in protection against diabetes and metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is associated with increased reactive oxygen generation leading to oxidative and pro-inflammatory processes that contribute to insulin insensitivity and disease progression [234,235]. The NQO1*2 null polymorphism in NQO1 has been associated with an increased risk of adverse lipid profiles, coronary artery disease and Type 2 diabetes related to metabolic syndrome [236,237]. Gaikwad et al. reported that NQO1-null mice developed insulin resistance resulting in a type 2 diabetes-like phenotype [238]. However, in contrast, in a subsequent study, Diaz-Ruiz et al. found that NQO1-null mice exhibited reduced fasting insulin levels and improved glucose metabolism [239]. Pharmacological stimulation of NADH oxidation via NQO1 catalysis has also been associated with amelioration of obesity [176] and hypertension [240] in mice.

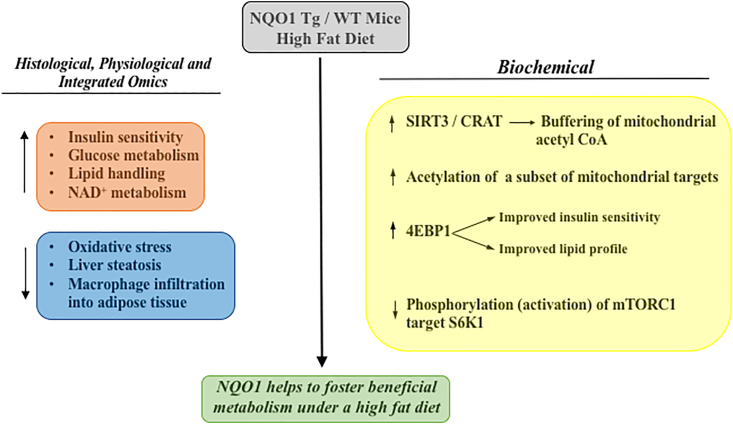

In recent collaborative work, we examined both the effects of overexpression of Nrf2 by deletion of Keap1 and NQO1 overexpression in transgenic mice fed high fat diets (HFD) [223]. While Nrf2 activation would be expected to activate more than 200 downstream genes [241], important similarities were observed between effects observed in systems where either Nrf2 was activated or the single gene NQO1 was overexpressed. Both Nrf2 activation and NQO1 overexpression in HFD-fed mice improved glucose and insulin metabolism, and improved lipid handling. Activation of Nrf2 however, unlike NQO1 overexpression, also protected against weight gain in animals on HFD so although NQO1 transgenic overexpressing (NQO1-Tg) mice developed obesity, they were still protected against liver steatosis and remained insulin sensitive. Mechanisms associated with the beneficial effects of NQO1 transgenesis were explored in more detail using integrated physiological data, histology and integrated metabolomics, proteomics and acetylomics. NQO1-Tg mice were protected from HFD-induced liver steatosis and macrophage infiltration in adipose tissues and metabolic signatures were consistent with improved glucose, NAD+ and lipid metabolism and acetylation of a subset of SIRT3 targets in mitochondria [223]. NQO1 overexpression in skeletal muscle of mice fed HFD also led to decreased phosphorylation of the mTORC1 downstream target S6K1 and increased accumulation of 4EBP1, biochemical changes associated with protection against type 2 diabetes, obesity, diabetic nephropathy and insulin resistance [[242], [243], [244], [245], [246], [247]]. A summary of the effects of NQO1 overexpression on nutritional excess as a result of high fat diet feeding is shown in Fig. 4. Interestingly, recent work has shown that the carotenoid astaxanthin reduces oxidative stress in a streptozotocin-induced diabetes model combined with high sugar and high fat. Of 120 targeted proteins and more than 13,000 diabetes mellitus targets, network analysis combined with transcriptional analysis identified NQO1 as one of the 3 key targets together with Col5A1 and Notch 2 responsible for the intersecting networks leading to astaxanthin-induced decreases in oxidative stress and reduced insulin resistance [248].

The effects of NQO1 on markers of nutritional excess caused by feeding a high fat diet. For detailed discussion of histological, physiological, omic and biochemical changes associated with NQO1 overexpression in mice fed a high fat diet, see reference 223.

Much more work remains to be done regarding the mechanisms of protection of both Nrf2 and NQO1 against the many aspects of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome as well as elucidating both their similarities and differences.

NQO1 and Alzheimer's disease

NQO1 has long been associated with early pathological changes in Alzheimer's disease (AD) and its expression correlates with the progression and localization of AD pathology in human brains [[249], [250], [251]]. NQO1 levels are increased in AD brains relative to age matched controls and importantly, elevated NQO1 expression was limited to brain regions affected by AD pathology [249]. Increased NQO1 was found in neurofibrillary tangles and also in the cytoplasm of hippocampal neurons in post mortem samples from AD patients but not from young brains or in age matched controls from non-AD patients [251] and NQO1 immunostaining demonstrated localization of NQO1 surrounding senile plaques [249]. NQO1 is increased by oxidative stress as a part of the Nrf2 battery of stress response genes and the elevation of NQO1 associated with AD pathology is commonly viewed as a neuroprotective response to the oxidative stress that accompanies AD [[249], [250], [251]]. The NQO1*2 polymorphism is much more prevalent in Asian populations [[127], [128], [129]] and, a meta-analysis concluded that this polymorphism was significantly associated with AD in Chinese populations [252]. A recent review concluded that understanding links between NQO1 and AD pathology may contribute to an understanding of mechanisms of disease and could lead to new therapeutic approaches [253].

A novel observation of potential relevance to neurodegenerative diseases was obtained in studies using NQO1 and NQO1*2 as model flavoproteins and their potential to co-aggregate with β-amyloid (Aβ1-42) known to form amyloid plaques in patients with Alzheimer's disease [254]. The NQO1*2 protein has a much lower affinity for FAD due to destabilizing effects in the FAD binding region distal from the position of the mutation resulting in rapid degradation of the protein via the proteasome [116,117,[119], [120], [121], [122], [123], [124], [125], [126]]. The FAD-destabilized human recombinant NQO1*2 or wild type FAD-depleted apo NQO1 markedly stimulated co-aggregation with β-amyloid in cell-free systems relative to FAD-competent wild type NQO1 [254]. Riboflavin depletion also led to instability of NQO1 and other flavoproteins and enhanced amyloid aggregation in cells [254]. Thus, a deficiency in FAD led to misfolding of flavoproteins, overload of the proteasomal protein quality control system and the resultant co-aggregation of flavoproteins with β-amyloid potentially contributing to protein folding disorders.

NQO1 and aging

NQO1 declines with aging [255,256] providing less efficient protection against oxidative stress at many levels. Overexpression of a quinone reductase homolog in yeast extends both chronological and replicative lifespan [257]. One of the more robust approaches to manipulate the rate of aging in animal models is caloric restriction (CR) and CR upregulates levels of NQO1 and the PMRS in liver and brain thus conferring protection against oxidative stress [155,219,255]. Overexpression of NQO1 and cytochrome b5 reductase, two NAD+ producing enzymes mimics aspects of CR in animals [258]. However, CR also resulted in improved survival of NQO1-knockout mice suggesting that although NQO1 may contribute to the effects of CR, it was not essential for the benefits of CR on lifespan [239]. A positive association of NQO1 with both maximal and median lifespan extension has been reported in a comprehensive analysis of gene expression changes of 17 known pharmacological, dietary and genetic lifespan-extending interventions applied to different strains, sexes and age groups of mice [259]. Feeding mice with the NQO1 substrate β-lapachone to mice in order to modulate the NAD+/NADH ratio prevented age-dependent declines of motor and cognitive function in aged mice [182]. In the latter study, both β-lapachone and CR demonstrated similar effects on body weight, gene expression changes, behavioral function and increased longevity [182]. The use of NAD+ precurors to increase cellular NAD+ levels has resulted in improvement of cardiovascular and other age-related functional deficits [[260], [261], [262]], although many aspects of targeting NAD metabolism as a therapeutic approach in aging remain to be defined [263]. Interestingly, a recent high throughput anti-aging drug screen identified 2 compounds from more than 2600 screened, both of which affected pyridine nucleotide redox ratios and one of these compounds functioned via NQO1 catalysis [264]. Given the proposed roles of NQO1 to ameliorate oxidative stress via multiple mechanisms, its function as a redox switch and capacity to generate NAD+ and influence proteostasis, the role of NQO1 in the aging phenotype is worthy of further examination.

Summary

In recent years we have gained more insights into the physiological roles of NQO1 and made significant advances in unveiling its complexities. NQO1 plays multiple physiological roles as a consequence of both its catalytic activity and its ability to directly interact with other proteins and RNA. Xenobiotic substrates for NQO1 have been well-characterized and some endogenous substrates have been proposed. However, the multiple roles of NQO1 across different cells and organ systems makes targeted inhibition of a single isolated function using pharmacological inhibitors a difficult challenge.

NQO1 is highly inducible in response to multiple forms of stress including oxidative stress and several protective mechanisms against oxidative damage have been characterized. Because NQO1 is expressed at high levels in many solid tumors, it has become a target for bioactivation of antitumor agents, and this may be particularly relevant if tumors have upregulated Nrf2 with a resultant increase in NQO1 levels. A role for NQO1 in disease states such as type 2 diabetes, the metabolic syndrome and Alzheimer's disease is beginning to emerge. Interestingly, in studies with mice fed a high fat diet, both Nrf2 upregulation and NQO1 overexpression led to improvements in glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity although there were significant differences in phenotypes particulary in body weight trajectories. In aging, the potential involvement of NQO1 in lifespan extension is in need of further characterization and mechanistic insight.

The observation that the pyridine nucleotide ratio determines the conformation of NQO1 as demonstrated by the binding of redox specific antibodies suggests that NQO1 may also serve as a redox sensor, a role previously suggested for other flavoproteins. The implications of altered NQO1 functionality, particularly with respect to interactions with other proteins and RNA, as a function of pyridine nucleotide redox state raises interesting redox-dependent signaling possibilities.

Funding

DR and DS were supported in part by

Declaration of competing interest

None.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to our colleagues Drs. Michel Bernier, Rafael de Cabo, Andrea Di Francesco and Kris Fritz for advice and many helpful suggestions.

The diverse functionality of NQO1 and its roles in redox control

The diverse functionality of NQO1 and its roles in redox control