The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

Cells use a variety of mechanisms to maintain optimal mitochondrial function including the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt). The UPRmt mitigates mitochondrial dysfunction by differentially regulating mitoprotective gene expression through the transcription factor ATFS-1. Since UPRmt activation is commensurate with organismal benefits such as extended lifespan and host protection during infection, we sought to identify pathways that promote its stimulation. Using unbiased forward genetics screening, we isolated novel mutant alleles that could activate the UPRmt. Interestingly, we identified one reduction of function mutant allele (osa3) in the mitochondrial ribosomal gene mrpl-2 that activated the UPRmt in a diet-dependent manner. We find that mrpl-2(osa3) mutants lived longer and survived better during pathogen infection depending on the diet they were fed. A diet containing low levels of vitamin B12 could activate the UPRmt in mrpl-2(osa3) animals. Also, we find that the vitamin B12-dependent enzyme methionine synthase intersects with mrpl-2(osa3) to activate the UPRmt and confer animal lifespan extension at the level of ATFS-1. Thus, we present a novel gene-diet pairing that promotes animal longevity that is mediated by the UPRmt.

The mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is a cellular pathway that mediates recovery of damaged mitochondria. Mitigation of mitochondrial dysfunction is critical due to the essential nature of the organelle. The UPRmt controls the expression of genes that help restore mitochondrial homeostasis via the bZIP transcription factor ATFS-1. The activation of the UPRmt is associated not only with extended animal lifespan but also with increased host protection during infection with bacterial pathogens. Using a genetic screen to identify pathways that activate the UPRmt, we recovered a novel reduction of function mutation in the mitochondrial ribosomal gene mrpl-2 that mediates protein translation in mitochondria. Interestingly, our isolated mrpl-2 mutant activates the UPRmt and promotes longevity when fed a specific diet which is low in the metabolite vitamin B12. We find that impaired function of methionine synthase, an enzyme that uses vitamin B12 as a cofactor to convert homocysteine to methionine, genetically interacts with the isolated mrpl-2 mutant to activate the UPRmt and extend lifespan. Our findings suggest that the lifespan-extending benefits of impaired mitochondrial translation and that of methionine restriction occur through a common mechanism that includes the activation of the UPRmt.

Introduction

Because of their endosymbiotic origin, mitochondria possess their own genome and ribosomes that are used to express and translate a minor portion of the mitochondrial proteome [1]. The mitochondrial genome encodes 13 (12 in C. elegans) subunits of the multimeric electron transport chain (ETC) complexes while the remaining components are expressed from the nuclear genome, translated on cytosolic ribosomes and imported into mitochondria using a sophisticated import pathway [2]. This requires a great deal of coordination between both the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes in order to efficiently assemble these multimeric ETC structures. Imbalances in mitonuclear coordination causes mitochondrial dysfunction that is sensed by cellular defense programs to help restore normal organelle function [3–5]. Retrograde signaling such as the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (UPRmt) is one type of defense mechanism that is used to mitigate mitochondrial dysfunction [6,7]. Here, decreased mitochondrial function is coupled to changes in gene expression that helps restore mitochondrial homeostasis. At the center of the UPRmt is the bZIP transcription factor ATFS-1 that coordinates the changes in gene expression associated with this mitochondrial stress response [8,9]. A defining characteristic of ATFS-1 is the presence of a mitochondrial targeting sequence that mediates its import into healthy mitochondria where it subsequently undergoes proteolytic degradation. Import efficiency is reduced in dysfunctional mitochondria allowing ATFS-1 to accumulate in the cytosol and be imported into the nucleus. ATFS-1 regulates a broad change in gene expression that in turn mediates mitochondrial recovery with roles in proteostasis, detoxification, and metabolic reprogramming [9].

Paradoxically, while a decline in mitochondrial function is associated with organismal aging and disease, there is considerable support that mild impairment can extend lifespan [10]. Conditions that reduce mitochondrial function and extend lifespan are also associated with the activation of the UPRmt. Evidence also exists demonstrating a requirement of the UPRmt for mitochondrial stress-induced longevity. For example, the UPRmt is required for the increase in lifespan that is observed in mitochondrial stressed animals with impaired ETC function [11,12]. Also, disruptions to mitochondrial ribosome function results in mitonuclear imbalances that extend lifespan in a UPRmt-dependent manner [3]. It is important to note that although UPRmt activation is correlated with conditions that promote lifespan extension, it is not an absolute predictor of this phenomenon nor is it always required [5].

In addition to promoting lifespan extension, UPRmt activation is also associated with promoting host survival during infection. Here, ATFS-1 regulates the expression of genes related to innate immunity including anti-microbial peptides, lysozymes and C-type lectins [9,13]. Consistently, ATFS-1 is required for protection during infection with pathogens that target mitochondrial function [13–15]. Also, priming the host for the UPRmt prior to infection significantly improves host resistance [13,16].

Here, we have identified a reduction of function allele in the C. elegans mitochondrial ribosome gene mrpl-2 using a forward genetics approach. We find that the mrpl-2 mutant exhibits extended lifespan and increased survival during pathogen infection. However, the benefits conferred by mrpl-2(osa3) were diet-dependent. We find that a diet low in vitamin B12 acts synergistically with the mrpl-2 mutant genetic background. Mechanistically, loss of the vitamin B12-dependent enzyme methionine synthase interacts with the mrpl-2 mutant to drive the activation of the UPRmt, thus promoting lifespan extension. Our data support a model in which genetically-induced mitonuclear imbalance and diet-mediated methionine restriction use a common mechanism to promote lifespan extension, including the activation of the UPRmt.

Results

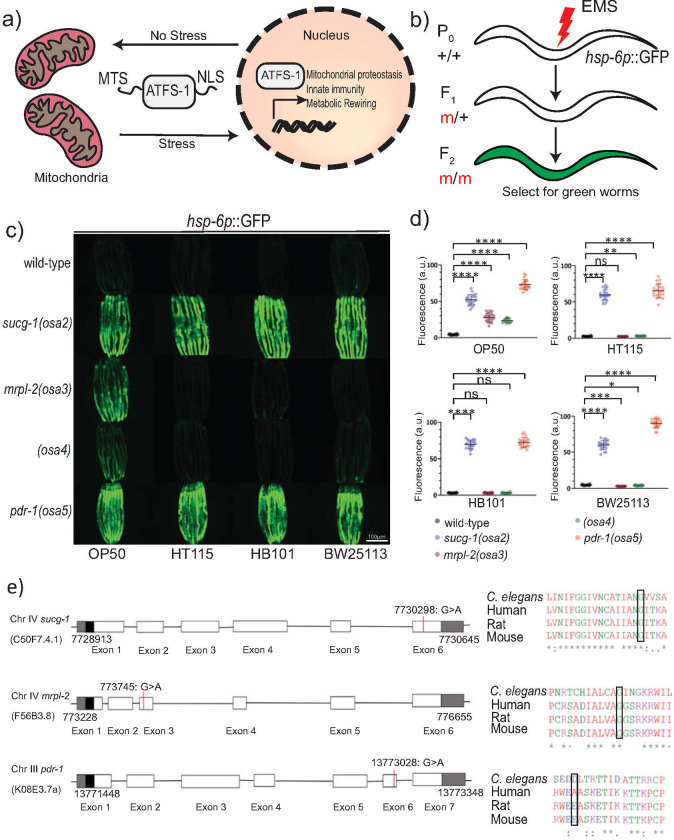

Forward genetic mutagenesis screen identifies novel alleles that activate the UPRmt in diet-dependent and independent manners

Because activation of the UPRmt is correlated with extended lifespan and increased survival during pathogen infection, we sought to perform a forward genetic screen to uncover novel alleles capable of activating the UPRmt using the strain SJ4100 hsp-6p::GFP (Fig 1A and 1B). C. elegans hsp-6 encodes the ortholog of the mitochondrial chaperone mtHSP70 and its expression is induced during the UPRmt [17]. We obtained four independent viable mutants from this screen that could activate the hsp-6p::GFP reporter (mutant alleles osa2-osa5) (Fig 1C and 1D).

Isolation of novel alleles that activate the UPRmt in diet-dependent and–independent manners.

(A) Schematic of the UPRmt response. (B) Schematic illustrating the strategy used to isolate mutants that activate the UPRmt using forward genetics. (C, D) Photomicrographs and quantification of hsp-6p::GFP expression for the four isolated mutants fed different diets of E. coli. The alleles were named osa2, osa3, osa4 and osa5. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20 worms); ns denotes not significant, * denotes p<0.05, ** denotes p ≤ 0.01, *** denotes p ≤ 0.001, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (E) Schematics of gene structure and protein alignment of sucg-1(osa2), mrpl-2(osa3), and pdr-1(osa5) with the indicated mutations and amino acid changes.

ATFS-1 is required for the development and/or fertility of mitochondrial stressed animals [9,18], prompting us to investigate the effect of its knockdown by RNAi in all our identified mutants. Interestingly, while loss of ATFS-1 slowed the development and reduced the fertility of osa2 and osa5 animals, it had negligible effects for osa3 and osa4 (S1A Fig). We therefore examined UPRmt activity in osa2-osa5 animals in the presence or absence of ATFS-1. Consistent with causing a delay in animal development, loss of ATFS-1 suppressed the induction of hsp-6p::GFP in osa2 and osa5 animals (S1B Fig). Surprisingly, hsp-6p::GFP expression was not induced in osa3 and osa4 animals even when grown with empty RNAi plasmid control bacteria (S1B Fig). RNAi by feeding in C. elegans uses the RNase III-deficient E. coli strain HT115 (E. coli K12-type strain) as opposed to the standard E. coli uracil auxotroph strain OP50 (E. coli B-type strain). Since we had performed the forward genetics mutagenesis using E. coli OP50, we hypothesized that the type of diet may be influencing the activation of the UPRmt in osa3 and osa4 animals. Indeed, we could recapitulate the absence of UPRmt activation in osa3 and osa4 animals using E. coli HT115 bacteria that lacked the empty RNAi plasmid (Fig 1C and 1D). We also tested another E. coli K12 strain BW25113 and the K12/B-type hybrid strain HB101 which similarly did not induce hsp-6p::GFP expression in osa3 and osa4 animals (Fig 1C and 1D). In contrast, the type of E. coli diet had no discernible effect on the activation of the UPRmt in the osa2 or osa5 mutant backgrounds (Fig 1C and 1D). Thus, the type of diet influences the activation of the UPRmt in the osa3 and osa4 genetic backgrounds.

We used whole genome sequencing to identify the genes responsible for the UPRmt induction observed in osa2-osa5. The allele osa2 contained a mutation (GGT➔AGT[359 Gly➔Ser] in sucg-1, the C. elegans homolog of SUCLG2 succinyl-CoA ligase subunit beta (Fig 1E). The allele osa3 contained a mutation GGA➔GAA[125Gly➔Glu] in mrpl-2, the C. elegans homolog of MRPL2 mitochondrial ribosomal protein L2 subunit (Fig 1E). Consistently, knockdown of MRPL-2 and other mitochondrial ribosome subunits was previously found to activate the UPRmt [3,5]. For the osa5 allele we identified a GAT➔AAT[329Asp➔Asn] mutation in pdr-1, the C. elegans homolog of Parkin (Fig 1E). Reintroducing the wild-type sucg-1 or mrpl-2 gene locus by germline transformation could rescue UPRmt activity back to wild-type levels for osa2 and osa3, respectively (S2A and S2B Fig). However, re-introduction of the wild-type pdr-1 locus into osa5 animals did not rescue UPRmt activity to wild-type levels (S2C Fig). Instead, germline transformation of wild-type animals with the pdr-1 gene locus containing the osa5 mutation was sufficient to induce the UPRmt (S2C Fig). In contrast, germline transformation of wild-type animals with the wild-type pdr-1 gene locus did not induce the UPRmt (S2C Fig). Together, this suggests that osa5 is a novel dominant allele of pdr-1. We were unable to map the gene responsible for the activation of the UPRmt in osa4 animals and therefore examined the connection between diet, genetic background, and UPRmt activation using mrpl-2(osa3) animals.

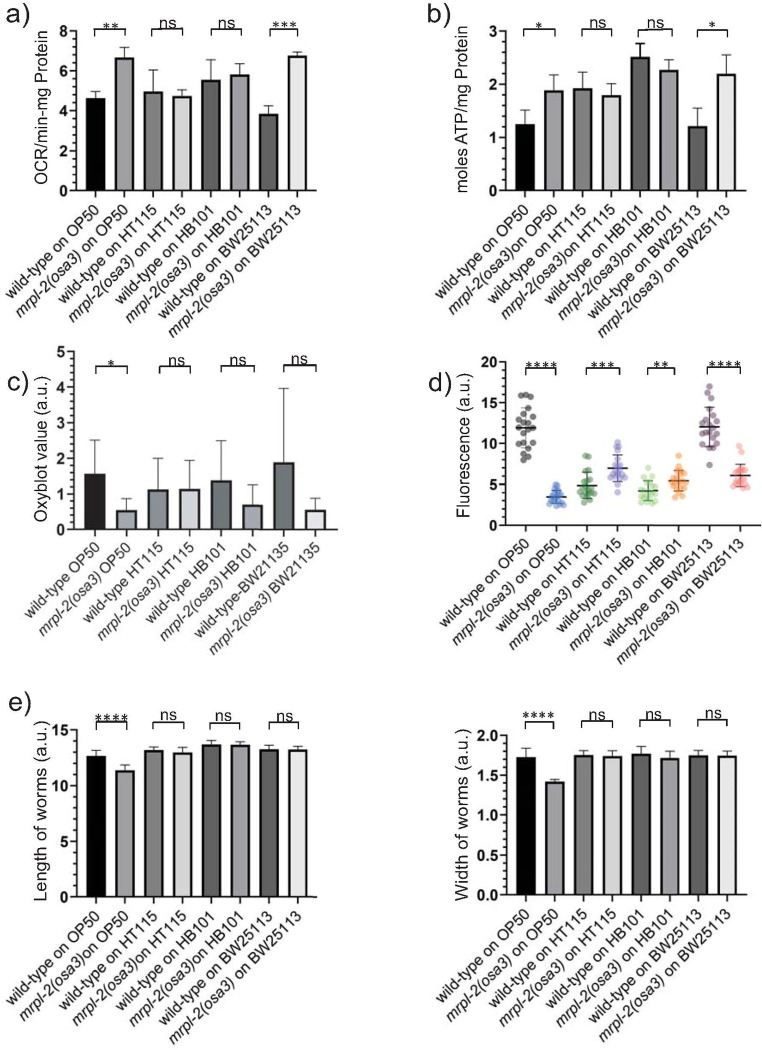

Diet influences mitochondrial function in mrpl-2(osa3) animals

We next examined various parameters of mitochondrial function in wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed the various E. coli diets. We first measured oxygen consumption levels which were surprisingly increased in mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50 and BW25113, but not HT115, and HB101 (Fig 2A). We observed a similar trend when measuring ATP levels which were increased in mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50 and BW25113, whereas no change occurred with HT115 and HB101 (Fig 2B). Increased mitochondrial activity or dysfunction can generate toxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) that perturbs protein homeostasis through the formation of carbonyl modifications. We therefore used the OxyBlot system which assesses protein carbonylation as a measure of oxidative damage. Interestingly, mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed a diet of E. coli OP50 showed reduced oxidative damage compared to wild-type (Figs 2C and S3). No change in oxidative damage was observed when mrpl-2(osa3) animals were fed diets of E. coli HT115, HB101, or BW25113 (Figs 2C and S3). Lastly, mitochondrial function was also examined through an assessment of mitochondrial membrane potential. Consistent with an activation of the UPRmt, mrpl-2(osa3) animals displayed reduced mitochondrial membrane potential when fed a diet of E. coli OP50 (Figs 2D and S4A). Mild increases in mitochondrial membrane potential were observed when mrpl-2(osa3) animals were fed diets of E. coli HT115 and HB101 (Figs 2D and S4A). Surprisingly, mitochondrial membrane potential was also reduced when mrpl-2(osa3) animals were fed a diet of E. coli BW25113 despite no observable activation of the UPRmt (Figs 2D and S4A).

Mitochondrial function is altered in mrpl-2(osa3) animals in a diet-dependent manner.

(A) Oxygen consumption rate determination for wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50, HT115, HB101, and BW25113. Oxygen consumption was normalized to total protein content (mean ±SD; n = 3); ns denotes not significant, ** denotes p ≤ 0.01, *** denotes p ≤ 0.001 (Student’s t test). (B) ATP production quantification for wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50, HT115, HB101, and BW25113. ATP levels are normalized to total protein content (mean ±SD; n = 3); ns denotes not significant, * denotes p ≤ 0.05 (Student’s t test). (C) Oxidative protein modification determination using the OxyBlot assay. OxyBlot values were normalized to actin for each sample and represented as arbitrary units (A.U.). (mean ± SD; n = 5); ns denotes not significant, * denotes p ≤ 0.05 (Student’s t test). (D) Mitochondrial membrane potential determination using TMRE and quantification for wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50, HT115, HB101, and BW25113 reflected as arbitrary units (A.U.). (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20 worms); ** denotes p ≤ 0.01, *** denotes p ≤ 0.001, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (E) Animal size quantification of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50, HT115, HB101, and BW25113. Animal size is expressed as the length and width of each animal and represented as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20 worms); ns denotes not significant, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test).

Slowed developmental rates are often a consequence of mitochondrial stress. However, we did not observe any significant change in developmental rates between wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) fed on the various diets (S4B Fig). While the development of mrpl-2(osa3) animals was not significantly different, we did notice that mrpl-2(osa3) animals appeared thinner and overall slightly smaller when fed E. coli OP50 whereas no difference was observed when these animals were fed E. coli HT115, HB101, or BW25113 (Fig 2E).

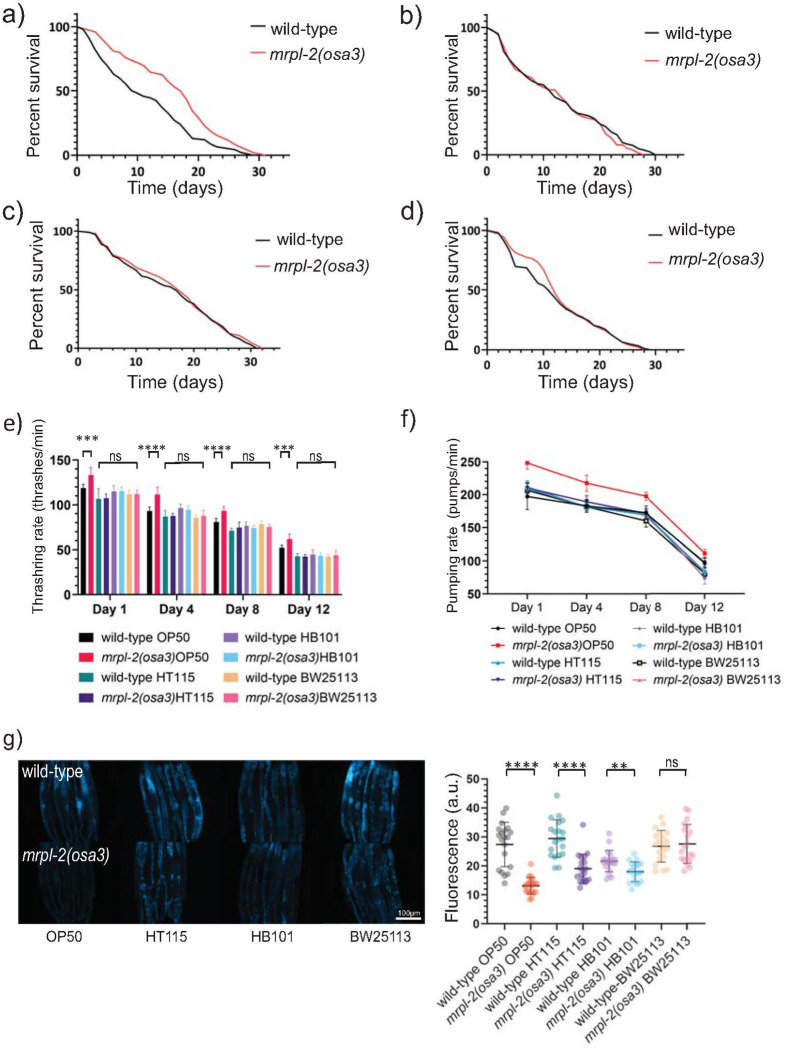

mrpl-2(osa3) extends lifespan and increases host resistance in a diet-dependent manner

We next examined lifespans of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed the various diets. As expected with the activation of the UPRmt, mrpl-2(osa3) animals lived longer than wild-type when fed E. coli OP50 (Fig 3A). No differences in lifespan between wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) were observed when fed E. coli HT115, HB101, and BW25113 which is consistent with a lack of UPRmt activation on these diets (Fig 3B–3D). Importantly, an extrachromosomal array consisting of the wild-type mrpl-2 gene locus suppressed the increased longevity of mrpl-2(osa3) animals in two independent transgenic lines resulting in normal (wild-type) lifespan levels (S5 Fig), indicating that mutation in mrpl-2 is the cause of the observed lifespan extension.

Diet-type determines lifespan in mrpl-2(osa3) animals.

(A-D) Lifespans of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli (A) OP50, (B) HT115, (C) HB101, and (D) BW25113. See S1 Table for all lifespan assay statistics. (E) Whole body thrashing rate quantification of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50, HT115, HB101, and BW25113. (mean ±SD; n ≥ 10 worms); ns denotes not significant, *** denotes p ≤ 0.001, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (F) Pharyngeal pumping rate quantification of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50, HT115, HB101, and BW25113 (mean ±SD; n ≥ 10 worms). (G) Photomicrographs and quantification of gut autofluorescence in wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); ns denotes not significant, ** denotes p ≤ 0.01, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test).

We then measured various physiological markers of aging between wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) under the different diets. We first measured thrashing rates which reflects body wall muscle integrity. We find that muscle function decline was less in mrpl-2(osa3) animals compared to wild-type when fed E. coli OP50 whereas no differences in thrashing rate was observed when mrpl-2(osa3) animals were fed other diets (Fig 3E). We then quantified pharyngeal pumping which is a reflection of the rate of food intake and found it to be higher in aged mrpl-2(osa3) animals compared to wild-type when fed E. coli OP50 whereas no difference was detected when fed E. coli HT115, HB101, and BW25113 (Fig 3F). Lastly, accumulation of lipofuscin is a hallmark of aging in C. elegans that is reflected as intestinal autofluorescence [19]. The greatest reduction in autofluorescence was observed when mrpl-2(osa3) animals were fed E. coli OP50 but only a mild difference was observed when fed E. coli HT115, HB101, and no difference for BW25113 (Fig 3G). Therefore, mrpl-2(osa3) slows physiological markers of aging when fed a diet of E. coli OP50.

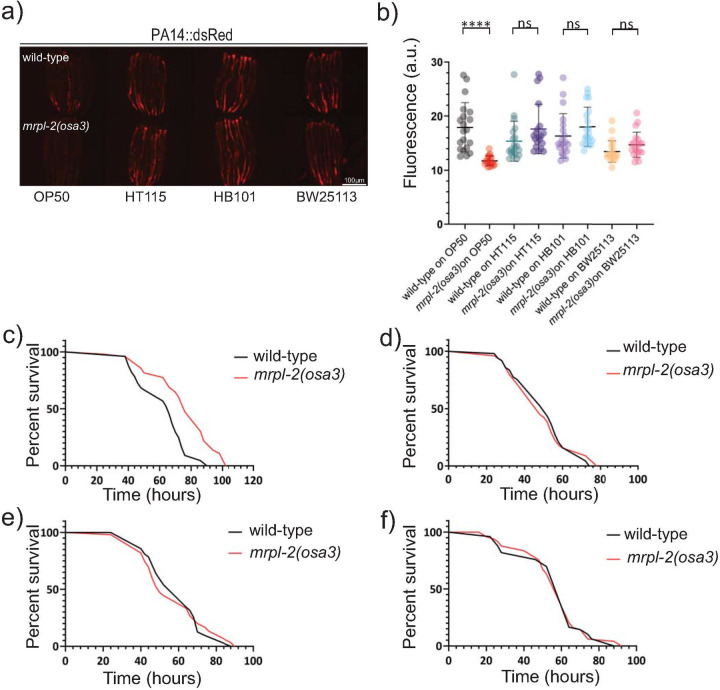

Next, we examined the effect of diet on the ability of mrpl-2(osa3) animals to survive infection with the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa [13]. Consistent with increased host resistance, pathogen colonization was lower in mrpl-2(osa3) animals that were previously fed E. coli OP50 whereas similar pathogen colonization levels were observed in mrpl-2(osa3) animals previously fed E. coli HT115, HB101, and BW25113 (Fig 4A and 4B). Accordingly, mrpl-2(osa3) animals survived significantly longer than wild-type animals during infection with P. aeruginosa if they were previously fed a diet of E. coli OP50 (Fig 4C). No difference in host survival was observed between wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals when each were previously fed diets of E. coli HT115, HB101, or BW25113 (Fig 4D–4F).

mrpl-2(osa3) animals survive longer during infection depending on their prior diet.

(A, B) Photomicrographs and quantification of P. aeruginosa PA14-dsRed expression of infected wild-type or mrpl-2(osa3) animals previously fed different diets of E. coli. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20 worms); ns denotes not significant, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (C-F) Survival analysis of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals infected with P. aeruginosa. E. coli diets prior to P. aeruginosa infection are (C) OP50, (D) HT115, (E) HB101, and (F) BW25113. See S1 Table for all survival assay statistics.

We next wished to confirm that mild dysfunction to mitochondrial translation was synergizing specifically with a diet of E. coli OP50 to induce the UPRmt. Here, we treated wild-type animals with doxycycline which was previously found to inhibit mitochondrial translation, activate the UPRmt and increase C. elegans lifespan [3]. We find that exposure of wild-type animals to a mild dose of doxycycline activated the UPRmt when fed a diet of E. coli OP50 but not HT115, HB101, or BW25113 (S6A Fig). In addition, exposure to a mild dose of doxycycline increased the lifespan of wild-type animals only when they were fed a diet of E. coli OP50, whereas no difference was observed when fed E. coli HT115, HB101, or BW25113 (S6B–S6E Fig). Thus, mild disruption to mitochondrial translation either through genetic (mrpl-2(osa3)) or chemical (doxycycline) means activates the UPRmt and extends lifespan in a diet-dependent manner.

Together, our data suggests an interplay exists between diet and the mrpl-2(osa3) genetic background that drives activation of the UPRmt. Hereafter, we focus on the diets of E. coli OP50 and HT115 to dissect the mechanisms behind this interaction.

Vitamin B12 availability synergizes with mrpl-2(osa3) to activate the UPRmt

We next explored the mechanism behind the relationship of diet and the activation of the UPRmt in mrpl-2(osa3) animals. A recent study found that E. coli OP50 is deficient in the nutrient vitamin B12 compared to E. coli HT115 [20]. We hypothesized that lower levels of vitamin B12 in the E. coli OP50 diet might interact with mrpl-2(osa3) to drive the activation of the UPRmt. Indeed, wild-type animals fed a diet of E. coli OP50 had lower levels of vitamin B12 compared to those fed a diet of E. coli HT115 (S7 Fig). We therefore supplemented the E. coli OP50 diet with two biologically active forms of vitamin B12, methylcobalamin and adenosylcobalamin, which are used as cofactors in the activation of associated effectors. Interestingly, we found that an E. coli OP50 diet supplemented with methylcobalamin or adenosylcobalamin was able to suppress the activation of hsp-6p::GFP in mrpl-2(osa3) animals (Fig 5A and 5B). The finding that either methylcobalamin or adenosylcobalamin could suppress the activation of the UPRmt is likely due to their ability to be interconverted [21]. We next measured lifespans of wild-type or mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed an E. coli OP50 diet supplemented with methylcobalamin. Consistent with attenuating the activation of the UPRmt, methylcobalamin supplementation suppressed the extended lifespan of mrpl-2(osa3) fed a diet of E. coli OP50 (Fig 5C).

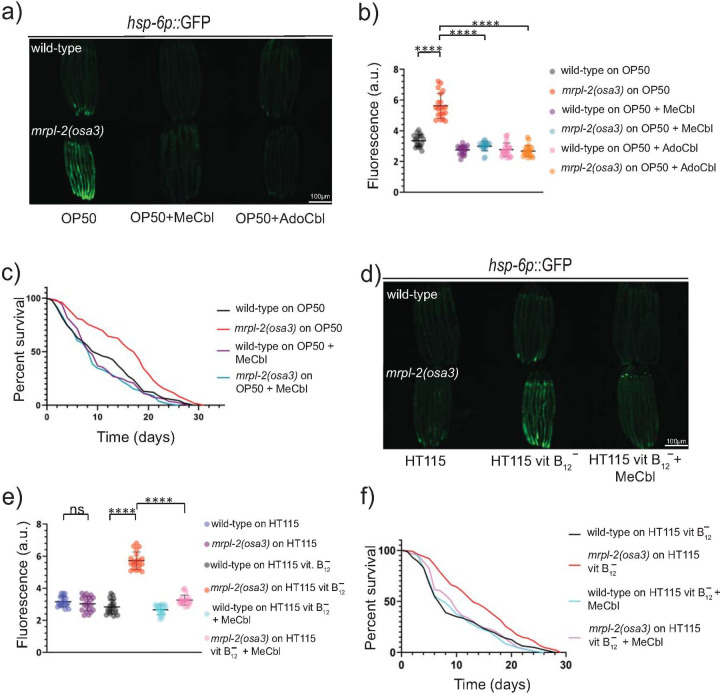

Vitamin B12 levels determine the activation of the UPRmt in mrpl-2(osa3) animals under different diets.

(A, B) Photomicrographs and quantification of hsp-6p::GFP expression in wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50 in the presence or absence of 0.2 μg/ml methylcobalamin or adenosylcobalamin. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20 worms); **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (C) Lifespans of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50 in the presence or absence of 0.2 μg/ml methylcobalamin. (D, E) Photomicrographs and quantification of hsp-6p::GFP expression in wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed vitamin B12-restricted E. coli HT115 in the presence or absence of 0.2 μg/ml methylcobalamin. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20); ns denotes not significant, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (F) Lifespans of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed vitamin B12-restricted E. coli HT115 in the presence or absence of 0.2 μg/ml methylcobalamin.

Next, we examined the consequences of restricting vitamin B12 levels from the diet of E. coli HT115 using a previously established technique [22]. Restricting vitamin B12 levels was able to activate the UPRmt in mrpl-2(osa3) animals but not in the wild-type, similar to when they were fed E. coli OP50 (Fig 5D and 5E). Supplementing with methylcobalamin attenuated UPRmt activity in vitamin B12-restricted mrpl-2(osa3) animals (Fig 5D and 5E). Consistent with an activation of the UPRmt, reducing vitamin B12 levels from the HT115 diet also extended the lifespan of mrpl-2(osa3) animals, which could be suppressed with methylcobalamin supplementation (Fig 5F). Together, our data suggest that the effect of diet on the activation of the UPRmt in the mrpl-2(osa3) background is due to differences in vitamin B12 content.

Mitonuclear imbalance and methionine restriction act in a common pathway to promote lifespan extension

Vitamin B12 is used as a cofactor for two separate enzymes: methionine synthase which mediates the conversion of homocysteine to methionine during the S-adenosylmethionine/methionine cycle, and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase which converts L-methylmalonyl-CoA to succinyl-CoA (Fig 6A) [21]. Therefore, we tested the effects of genetically disabling these pathways under a vitamin B12 replete diet of HT115 using mutants in methionine synthase, (metr-1(ok521)) and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase (mmcm-1(ok1637)). Interestingly, metr-1(ok521) or mmcm-1(ok1637) individual loss of function mutants activated the UPRmt when they were fed a diet of HT115 (Fig 6B and 6C). However, no further enhancement of the UPRmt was observed for each mutation in combination with the mrpl-2(osa3) background (Fig 6B and 6C).

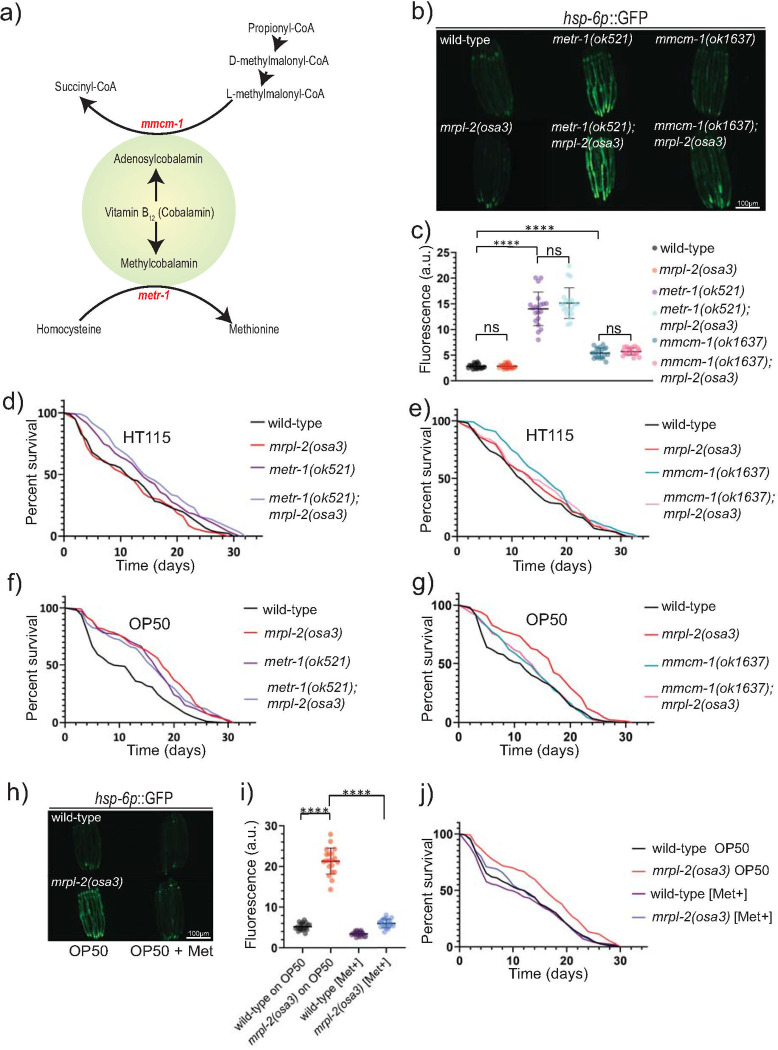

Methionine supplementation suppresses UPRmt activation in mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed a vitamin B12 deficient diet.

(A) Schematic illustration of vitamin B12-dependent metabolic pathways. (B, C) Photomicrographs and quantification of hsp-6p::GFP expression of wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), metr-1(ok521), mmcm-1(ok1637), metr-1(ok521); mrpl-2(osa3), and mmcm-1(ok1637); mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli HT115 diet. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20); ns denotes not significant, **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (D) Lifespans of wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), metr-1(ok521), metr-1(ok521); mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli HT115 diet. (E) Lifespans of wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), mmcm-1(ok1637), mmcm-1(ok1637); mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli HT115 diet. (F) Lifespans of wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), metr-1(ok521), metr-1(ok521); mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli OP50 diet. (G) Lifespans of wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), mmcm-1(ok1637), mmcm-1(ok1637); mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli OP50 diet. (H, I) Photomicrographs and quantification of hsp-6p::GFP expression of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli OP50 diet in the presence or absence of 10 mM methionine. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n 20); denotes p 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (J) Lifespans of wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) fed an E. coli OP50 diet in the presence or absence of 10 mM methionine.

We then examined the effects of mmcm-1(ok1637) or metr-1(ok521) on the lifespan of mrpl-2(osa3) fed a vitamin B12-replete diet of E. coli HT115 or when fed a diet of E. coli OP50. Neither mmcm-1(ok1637) or mmcm-1(ok1637); mrpl-2(osa3) animals exhibited any significant change in lifespan fed a diet of E. coli HT115 (Fig 6E). Unexpectedly, a modest but significant increase in lifespan was observed in metr-1(ok521) single mutants fed E. coli HT115 (Fig 6D), previously found to have normal rates of aging when fed E. coli OP50 [23]. However, there was no significant difference in lifespan between metr-1(ok521) and metr-1(ok521); mrpl-2(osa3) mutants fed a diet of E. coli HT115 (Fig 6D). In contrast, a greater lifespan extension was observed in metr-1(ok521) animals fed the E. coli OP50 diet to levels comparable with E. coli OP50-fed mrpl-2(osa3) (Fig 6F). However, and interestingly, no further extension was observed in metr-1(ok521); mrpl-2(osa3) double mutant animals fed E. coli OP50 (Fig 6F). Surprisingly, although the lifespan of mmcm-1(ok1637) was not significantly extended compared to wild-type when fed a diet of E. coli OP50, mmcm-1(ok1637) nonetheless reduced the lifespan extension of mrpl-2(osa3) (Fig 6G). This suggests that mrpl-2(osa3) extends lifespan when fed a diet of OP50 in a MMCM-1-dependent manner.

Because the lifespan extensions of mrpl-2(osa3) and metr-1(ok521) animals were not additive in the double mutant background suggests that mitonuclear imbalance and methionine restriction may use a common pathway(s) to regulate aging. Indeed, wild-type animals fed a diet of E. coli OP50 were found to have lower levels of methionine compared to those fed a diet of E. coli HT115 (S8 Fig). In addition, supplementation with methionine, but not other amino acids, resulted in a near complete suppression of the UPRmt in mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed a diet of E. coli OP50 (Figs 6H and 6I and S9). Consistently, methionine supplementation also completely suppressed the increase in longevity observed with mrpl-2(osa3) animals fed E. coli OP50 (Fig 6J).

ATFS-1 mediates extended lifespan resulting from mitonuclear imbalance or methionine restriction

We next performed transcriptomics to evaluate the changes in gene expression occurring during mitonuclear imbalance and methionine restriction using mrpl-2(osa3) and metr-1(ok521) animals, respectively. We hypothesized that mrpl-2(osa3) and metr-1(ok521) extended lifespan using at least one common pathway since the lifespan of the double mutant was not additive. Using a cutoff p-value of <0.05 (after Benjamini-Hochberg correction), our transcriptomic analysis indicated that there were relatively fewer genes that were differentially expressed in metr-1(ok521) animals relative to wild-type animals compared to those differentially expressed in mrpl-2(osa3) (Fig 7A–7C and S2 Table). However, there was considerable overlap between the genes that were differentially expressed in each genetic background. Of the 46 genes that were upregulated in metr-1(ok521), 26 were shared with mrpl-2(osa3) (Fig 7C). Similarly, of the 88 genes that were downregulated in metr-1(ok521) animals, 47 were in common with mrpl-2(osa3) (Fig 7C).

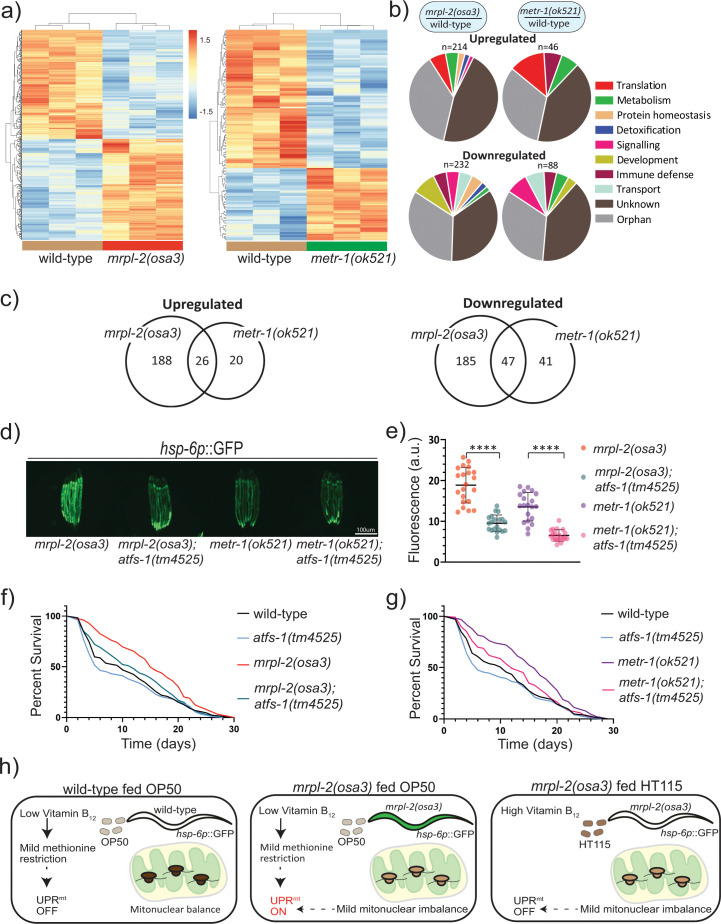

ATFS-1/UPRmt mediate the lifespan extension of mitonuclear imbalance and methionine restriction.

(A) Heat maps representing gene expression changes in wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), and metr-1(ok521) fed an E. coli OP50 diet. Genes were considered as differentially expressed if there was a significance difference of p ≤ 0.05 (after Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (B) Functional categories of differentially expressed genes. (C) Venn diagram of differentially expressed genes shared between mrpl-2(osa3) and metr-1(ok521). (D, E) Photomicrographs and quantification of hsp-6p::GFP expression for mrpl-2(osa3), mrpl-2(osa3); atfs-1(tm4525), metr-1(ok521), and metr-1(ok521); atfs-1(tm4525) fed a diet of E. coli OP50. Quantification of fluorescence intensities expressed as arbitrary units (A.U.); (mean ±SD; n ≥ 20); **** denotes p ≤ 0.0001 (Student’s t test). (F) Lifespans of wild-type, mrpl-2(osa3), atfs-1(tm4525), and mrpl-2(osa3); atfs-1(tm4525) fed a diet of E. coli OP50. (G) Lifespans of wild-type, metr-1(ok521), atfs-1(tm4525), and metr-1(ok521); atfs-1(tm4525) fed a diet of E. coli OP50. (H) Model. Wild-type animals fed a diet of E. coli OP50 experience a mild vitamin B12 restriction which reduces methionine synthase activity resulting in a subtle methionine restriction that is insufficient to activate the UPRmt. However, the UPRmt is activated in combination with the mild mitonuclear imbalance of the mrpl-2(osa3) reduction of function mutant which results in extended lifespan. In contrast, methionine supply is higher when fed a vitamin B12 replete diet of E. coli HT115, and therefore the mild mitonuclear imbalance of mrpl-2(osa3) mutant alone is incapable of inducing the UPRmt in this scenario resulting in animals that display normal aging rates.

Since both mitonuclear imbalance and methionine restriction were able to induce the UPRmt, we suspected that this pathway may be required for their effects on lifespan. Therefore, we next examined whether the increased longevity of mrpl-2(osa3) or metr-1(ok521) animals required the UPRmt by using the atfs-1(tm4525) reduction of function mutant. As expected, loss of ATFS-1 reduced the activation of the UPRmt in OP50-fed mrpl-2(osa3) and metr-1(ok521) animals (Fig 7D and 7E). Also, loss of ATFS-1 suppressed the increase in animal lifespan observed with mrpl-2(osa3) fed a diet of E. coli OP50 while having no significant effect in an otherwise wild-type background (Fig 7F). This is consistent with previous reports illustrating the need for the UPRmt for mitonuclear imbalance-induced lifespan extension [3]. Interestingly, atfs-1 reduction of function also suppressed the increase in lifespan resulting from metr-1(ok521) methionine restriction (Fig 7G). Thus, ATFS-1 and the UPRmt are required for lifespan extension resulting from both mitonuclear imbalance and methionine restriction.

Discussion

Our data suggests that the mrpl-2(osa3) allele is a reduction of function allele that creates a sensitized background for UPRmt activation and that the type of diet can tip the balance in its favor (Fig 7H). Vitamin B12 availability appears to be the metabolite that determines whether a diet will activate the UPRmt in the mrpl-2(osa3) background via the methionine synthase pathway. Consistently, under vitamin B12 replete conditions, the level of methionine restriction is insufficient to activate the UPRmt in the mrpl-2(osa3) sensitized background and to extend lifespan. Interestingly, we find that disruption to the vitamin B12-dependent methionine synthesis pathway via inactivation of METR-1 also activates the UPRmt and can extend animal lifespan. While bacterial diet is the main source of methionine for C. elegans, this amino acid can also be synthesized to a small degree via METR-1 and thus, reduced function of METR-1 results in a sensitized condition of methionine restriction [23]. Importantly, we find that a reduction of function mutation in mrpl-2 and mild methionine restriction use a common mechanism of longevity regulation, including the need of the UPRmt regulator ATFS-1.

Diet is an important determinant controlling organismal aging [24]. While dietary restriction has long been appreciated in mediating lifespan extension [25,26], there is a growing recognition that the type of diet and genetic background of the host can interact in order to control aging rates. This has been observed in a number of cases in C. elegans. For example, a mutation in the C. elegans 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C) dehydrogenase homolog alh-6, which mediates the conversion of P5C to glutamate during proline metabolism in mitochondria, displays reduced lifespan when fed on the E. coli strain OP50, but not when fed with the strain HT115 [27]. The reduced lifespan observed for alh-6 mutants grown on E. coli OP50 is due to increased accumulation of P5C that results in mitochondrial dysfunction. A second example of how gene-diet can affect lifespan is seen with a mutation in the rict-1 gene, the C. elegans homolog of a component of the Target of Rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2). Lifespan of rict-1 mutants fed E. coli OP50 is reduced compared to that observed using the E. coli strain HB101 [28]. Interestingly, rict-1 mutants tend to avoid the HB101 strain more often than OP50 resulting in less feeding and a dietary restriction-induced increase in longevity. More recently, loss of the kinase FLR-4 was shown to increase C. elegans longevity when fed E. coli HT115 but not OP50, through diet-specific activation of p38 MAPK and xenobiotic gene expression [29]. Our study indicates that a specific genetic background can synergize with a diet of low vitamin B12 to promote lifespan extension via activation of the UPRmt. It is interesting that vitamin B12 restriction was previously shown to reduce, rather than increase, lifespan duration [22]. It is possible that the sensitized mrpl-2(osa3) background requires a lesser degree of vitamin B12 restriction that promotes, rather than antagonizes, lifespan. Indeed, the activation of the UPRmt and increase in longevity of mrpl-2(osa3) animals required less vitamin B12 restriction (four generations of growth on vitamin B12-deficient E. coli) than was previously reported which reduced the lifespan of wild-type animals (following five generations of growth on vitamin B12-deficient E. coli) [22]. Also interesting is that a vitamin B12-replete diet of HT115 was previously shown to promote host protection against P. aeruginosa infection compared to a vitamin B12-restricted diet of OP50 [20], whereas our study discovered the opposite trend. However, the aforementioned protection occurred in the context of P. aeruginosa-mediated liquid-killing which reduces animal survival through the production of iron-binding siderophores [30]. In our current study, reduced vitamin B12 supply allowed mrpl-2(osa3) animals to survive longer during P. aeruginosa slow-killing which results from pathogen colonization of the gut [31]. This suggests that the beneficial effects of gene-diet interactions are context-dependent.

We also show that a reduction of function mutation in a mitochondrial ribosome gene converges with methionine restriction to promote lifespan at the level of the UPRmt. Mitonuclear imbalance was previously shown to increase animal longevity which required the UPRmt regulator UBL-5 [3]. Our study supports this finding by demonstrating a requirement of ATFS-1 for the extended lifespan of mrpl-2(osa3) fed a low vitamin B12 diet. Also, while an association between methionine restriction and lifespan extension has previously been reported [32], to our knowledge this is the first connection between this pathway and the activation of the UPRmt. While the mechanism behind the activation of the UPRmt resulting from methionine restriction was not explored, we do show a requirement for ATFS-1 in mediating the observed extension in longevity. The association between ATFS-1/UPRmt and the extended lifespan that is observed with mitochondrial stress remains controversial [5,12,18,33]. Certain conditions that activate the UPRmt are associated with extended lifespan and require ATFS-1 or other regulators of this stress response pathway. This includes mitonuclear imbalance [3], ETC dysfunction [12], and more recently from the loss of two neuronal epigenetic regulators [34]. Contrary to these findings, ATFS-1 had no role in regulating the lifespan increase observed with RNAi knockdown of the cytochrome c oxidase 1 gene cco-1, despite it reducing the expression of the UPRmt reporter [5]. Also, ATFS-1 was not required for the lifespan extension observed with transaldolase inhibition despite an activated UPRmt [33]. Furthermore, constitutive activation of ATFS-1 does not extend animal lifespan but rather, accelerates aging [5]. Our finding that ATFS-1 is required for the increased longevity of mrpl-2(osa3) animals is in line with previous observations demonstrating a requirement of the UPRmt for mitonuclear imbalance-induced longevity [3]. We have also shown that mild methionine restriction could also activate the UPRmt and extend lifespan in an ATFS-1-dependent manner. One possibility is that the requirement of ATFS-1 and the UPRmt for longevity is highly context-dependent and thus is only revealed during specific types of mitochondrial stress such as the conditions presented in this study. Furthermore, the regulation of lifespan by the UPRmt may also be dependent on the strength of mitochondrial stress encountered. For example, the matrix peptide exporter HAF-1 regulates the UPRmt under conditions of mild mitochondrial stress but not under elevated levels of dysfunction [9,35]. Future work will now focus on identifying the mechanism of UPRmt activation and lifespan extension occurring with methionine restriction which may help resolve these inconsistencies further.

Materials and methods

C. elegans and bacterial strains

C. elegans strains were maintained on nematode growth medium (NGM) using previously established methods [36] and cultured at 20°C. Various previously reported C. elegans strains were obtained from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (CGC) and include: N2 Bristol [36], zcIs13[hsp-6p::GFP], metr-1(ok521), mmcm-1(ok1637). Strains identified in this study include: sucg-1(osa2), mrpl-2(osa3), osa4, and pdr-1(osa5). All mutant strains were backcrossed at least four times prior to use. Transgenic rescue worm strains were as follows: sucg-1(osa2) [sucg-1+], mrpl-2(osa3) [mrpl-2+], pdr-1(osa5) [pdr-1+], N2 [pdr-1+], and N2 [pdr-1(osa5)].

The following bacterial strains were also used in this study: E. coli strains OP50, HB101, HT115, and BW25113, as well as P. aeruginosa PA14 and P. aeruginosa PA14-dsRed. E. coli strains were obtained from the CGC and P. aeruginosa strains were a gift from Dr. Joao Xavier (MSKCC).

EMS mutagenesis

Approximately 2000 SJ4100 animals were harvested from NGM plates with S-basal, washed twice to remove bacteria and resuspended in 2 ml S-basal. 2 ml of 2X ethyl methyl sulfonate (EMS) solution (60 μM) was added to worm suspension and placed on a rocker for 4 hrs. After mutagenesis, worms were washed three times with S-basal, resuspended in 0.5 ml S-basal and plated onto seeded NGM plates. After overnight incubation, 50 adult worms were singled out into NGM plates and allowed to grow until F2 generation (7 days). F2 worms showing green fluorescence were selected for further study.

Germline transformation

We used germline transformation to rescue the phenotypes associated with sucg-1(osa2), mrpl-2(osa3), and pdr-1(osa5) using standard techniques [37]. PCR fragments were generated consisting of the promoter, open reading frame, and 3’UTR of each gene and microinjected at 10 ng/μl along with Pmyo-2::mCherry plasmid at 5 ng/μl as a co-injection marker. Promoter lengths used for germline transformation experiments were as follows: mrpl-2 (533 bp), sucg-1 (2153 bp), and pdr-1 (1613 bp). Primer sequences used to PCR amplify each rescue fragment were as follows: mrpl-2: ttcacagccagactccaatg and gctatttgccgatttgtcgt, sucg-1: gcagctccttctgatcttgg and ggaagggtatgccattttga, pdr-1: gcgcctcttcatgattagca and catttgttgctgctgttgct. For [pdr-1(osa5)] rescue PCR, pdr-1(osa5) genomic DNA was used as a template. At least two independent transgenic lines were used from each transformation to test for rescue.

Microscopy

All fluorescent reporter expression assays were conducted using a Zeiss Observer Z1 upright microscope. Worms were anesthetized using 2.5 mM sodium azide in S-Basal and arranged on agarose pad-lined glass microscopy slides for visualization. ImageJ software was used for quantification of fluorescence intensity. Background fluorescence was subtracted from the intestinal fluorescence and divided by worm size to generate a fluorescence intensity value. All photomicrographs show a collection of representative animals. For quantification, at least 20 worms were scored blindly in three independent replicates.

Mitochondrial activity assays

Oxygen consumption rate (OCR) assay

The OCR assay was performed according to (Zuo et al., 2017) using the MitoXpress Xtra oxygen consumption assay kit (Agilent, USA). Approximately 100–150 worms were recovered from each bacterial diet plate and washed three times with S-basal solution to remove excess bacteria. The worms were then transferred to wells of a 96-well plate in a final sample volume of 90 μl. Then 10μl of the oxygen probe was added to each sample. The wells of the 96 well plate were then covered with two drops of mineral oil and immediately read using a Synergy Neo 2 plate reader using Gen5 software (BioTek, Wisnooski, VT, USA) in a time-resolved fluorescence mode with 380 nm excitation and 650 nm emission filters.

Measurement of ATP production

ATP was quantified using a bioluminescence ATP measurement kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Worms were collected from NGM plates and washed three times in S-basal to remove bacteria and frozen at -80°C overnight. Before assessment, the samples heated to 95°C for 15 minutes and then cooled on ice for 5 minutes. The samples were then centrifuged at 14,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C and the supernatant used to measure ATP. 10 μl of each sample were transferred into 96-well plates in triplicates. The ATP assay solution was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 90 μl of the assay solution was then added to each sample. The sample wells were read on Synergy Neo 2 plate reader using Gen5 software (BioTek, Wisnooski, VT, USA) with a luminometer filter. An ATP standard curve was generated and the ATP concentration for each sample was calculated based on the standard curve.

Quantification of mitochondrial membrane potential

To assess mitochondrial membrane potential, worms were grown on NGM media seeded with particular E. coli diets containing 1.25 nM tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester (TMRE) at 20°C for 3 days and visualized at the L4 stage.

Measurement of protein oxidation by OxyBlot

The OxyBlot protein oxidation detection kit (Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA, USA) was used to measure the level of protein oxidation. Worms were collected from each condition, washed with S-basal to remove bacteria and frozen to -80°C. After one hour, the samples were thawed and 100 μl of lysis buffer was added. Worms were homogenized using TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA). The DNP reaction mixture was prepared by adding 35 μg protein for each sample adjusted in 7 μl, 3 μl of 15% SDS and 10 μl of DNP solution. The mixture was kept at room temperature for 15 min, then 7.5 μl of Neutralization buffer was added. The samples were then loaded and run in 10% SDS-PAGE gels. Next, they were transferred to nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA) and blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1h. After washing with 1X PBS, the membrane was incubated with the first antibody (1:150) overnight at 4°C and then for 1h with the secondary antibody (1:300) at room temperature. Membranes were incubated with ECL plus detection reagent (Bio-Rad) and scanned using Chemiluminescent scanner (Bio-Rad). Band densities in a given lane were analyzed using ImageJ and added together as previously described [38]. Afterwards, the membranes were incubated with 15% hydrogen peroxide for 30 min at room temperature and treated with actin antibody. OxyBlot values were then normalized to actin for each sample.

Development and fertility assays

Worm development was assessed by first synchronizing animals at the L1 stage and then quantifying developmental stage each day for 3 days. Approximately 100 animals were used for this assay. Developmental stage was scored based on vulva development stage. For the fertility assay, animals at the L4 stage were transferred to fresh seeded plates daily and the number of progeny on each plate counted.

Thrashing assay

Worms were grown on NGM agar plates seeded with each E. coli bacterial strain until they reached the L4 stage of development. On days 1, 4, 8 and 12 the rate of animal movement was measured by quantifying their thrashing rate. Individual worms were placed in a 10 μl drop of S-basal on a microscope slide. After one minute of acclimation, the number of bends within 10 seconds were counted for each worm (with a total of 10 worms per experiment) blindly for a total of three biological replicates. One body bend was recorded as one rightward and one leftward body bend. The data was represented as number of thrashes per minute.

Pumping rate

Pharyngeal contractions were recorded for each animal under high magnification using a Zeiss Observer Z1 microscope. Worms were transferred onto a new plate and allowed to acclimate for a few minutes. Pharyngeal pumping was then counted for 30 seconds for each worm for a total of three biological replicates. The data was represented as pumps per minute.

Vitamin B12 restriction protocol

E. coli OP50 was grown in M9 medium at 37°C for 3 days. The bacteria were inoculated every 3 days into fresh M9 medium to be used as a food source for C. elegans [22].

To prepare B12-deficient worms, two to three L4 worms from the control plate were transferred onto plates containing B12-deficient M9 medium seeded with B12-deficient E. coli. Worms were grown on B12-deficient media for four generations until analysis [22].

Lifespan analysis

All lifespan experiments were performed at 20°C. One hundred animals at the L4 stage were maintained on the E. coli strain for the duration of the assay and transferred every 1–2 days until animals no longer produced progeny. Animals were considered dead if they did not respond to touch using the platinum wire. Worms were censored if they escaped the plate or if they ruptured at the uterus. For supplementation of methylcobalamin or adenosylcobalamin, each metabolite was spread over the bacterial lawn to a final concentration of 0.2 μg/ml. Methionine and other amino acids were added to NGM media to a final concentration of 10μM. Doxycycline was added at a concentration of 6 μg/ml. GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) was used to calculate statistical significance where p-values were generated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical analysis was performed as previously described [39]. In order to achieve sufficient statistical power, three biological replicates were used for each lifespan experiment starting with 100 animals per plate. For each experiment where there were more than two strains, the log-rank test was performed on each strain individually compared to the control strain. Only experiments in which all three biological replicates showed identical statistics were considered. In all cases, p-values <0.05 are considered significant. Each lifespan figure represents one lifespan experiment. All lifespan trials and their statistics are provided in S1 Table.

C. elegans pathogen infection assays

Worms were age-matched at the L4 stage by harvesting eggs using bleach/NaOH treatment of gravid hermaphrodites. Eggs were aliquoted on NGM plates containing E. coli (OP50, HT115, HB101, or BW25113) and then 50 L4 worms were transferred to P. aeruginosa PA14 infection plates. To prepare infection plates, PA14 was inoculated from a fresh culture plate and grown overnight at 37°C. The following day 15 μl of PA14 overnight culture was spotted onto NGM media plates. Plates were incubated overnight at room temperature and then transferred to 37°C for an overnight incubation and used for the survival assay the following day. Animal deaths were recorded daily every 2 hrs for a 12 hr period each day. Statistical analysis was performed as described for the lifespan assays.

To assess the level of infection, we grew wild-type and mrpl-2(osa3) animals on the various E. coli diets until the L4 stage at which time animals were transferred to plates containing P. aeruginosa expressing RFP. Infection levels were then measured based on the degree of fluorescence emitted in the worm gut lumen.

Determination of vitamin B12 levels

Vitamin B12 levels were obtained using the Vitamin B12 ELISA Kit (Biovision). Around 2000 synchronized worms per biological replicate were grown on E. coli OP50 and HT115 plates, washed in S-basal, harvested, and homogenized in lysis buffer. Supernatants were used for determining the vitamin B12 content in samples following manufacturer’s instructions.

Determination of methionine levels

Methionine content was determined using the Methionine Fluorescence Assay Kit (Abcam) and each experiment was performed in three biological replicates. Around 500 worms were grown on E. coli OP50 and HT115 plates, washed three times in S-basal, and then in 100 μl of Methionine assay buffer. Supernatants were used for determining the methionine content according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA sequencing analysis

Trizol extraction method was used to recover total RNA from worms and RNA was purified using Direct-zol RNA Kit (Zymo Research, CA, USA). An Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer was used to assess RNA integrity. Library construction and sequencing was done by Novogene Inc. (CA, USA). In short, mRNA was enriched using oligo(dT) beads and rRNA removed using the Ribo-Zero kit. mRNA was fragmented, followed by synthesis of first and second strand cDNA synthesis. Then sequencing adapters were ligated and the double-stranded cDNA library completed through size selection and PCR enrichment. The library was sequenced using an Illumina Hiseq 4000 following manufacturer’s instructions for paired-end 150-bp reads. The raw data was cleaned by removing adapter sequences, reads containing poly-N and low-quality reads (Q<30) using Trimmomatic [40]. Tophat v.2.0.9 [41] was used to align clean reads to the C. elegans reference genome. The mapped reads from each sample was assembled using Cufflinks v.2.1.1 [41]. HTSeq v.0.6.1 [42] was used to count the number of reads mapped to each gene. In addition, the reads per kilobase million (RPKM) of each gene was calculated based on the length of the gene and the number of reads mapped to it. Differential expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 R package (v.1.10.1) [43]. Relative expression of genes with Benjamini-Hochberg corrected P-values (Padj)<0.05 were considered to be differentially expressed. Heatmaps were generated with pheatmap in R Studio.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Caenorhabditis Genetic Center which is funded by the NIH Office of Research Infrastructure (P40 OD010440) for providing some of the worm strains used in this study.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

A novel gene-diet interaction promotes organismal lifespan and host protection during infection via the mitochondrial UPR

A novel gene-diet interaction promotes organismal lifespan and host protection during infection via the mitochondrial UPR