- Altmetric

Energy relaxation of photo-excited charge carriers is of significant fundamental interest and crucial for the performance of monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides in optoelectronics. The primary stages of carrier relaxation affect a plethora of subsequent physical mechanisms. Here we measure light scattering and emission in tungsten diselenide monolayers close to the laser excitation energy (down to ~0.6 meV). We reveal a series of periodic maxima in the hot photoluminescence intensity, stemming from energy states higher than the A-exciton state. We find a period ~15 meV for 7 peaks below (Stokes) and 5 peaks above (anti-Stokes) the laser excitation energy, with a strong temperature dependence. These are assigned to phonon cascades, whereby carriers undergo phonon-induced transitions between real states above the free-carrier gap with a probability of radiative recombination at each step. We infer that intermediate states in the conduction band at the Λ-valley of the Brillouin zone participate in the cascade process of tungsten diselenide monolayers. This provides a fundamental understanding of the first stages of carrier–phonon interaction, useful for optoelectronic applications of layered semiconductors.

The primary stages of carrier relaxation in atomically thin transition metal dichalcogenides are hardly accessible due to their fast timescales. Here, the authors measure the first stages of carrier–phonon interaction in monolayer WSe2 via a series of periodic maxima in the hot photoluminescence intensity, assigned to phonon cascades.

Introduction

The optical properties of group VI transition metal dichalcogenide monolayer (1L-TMD) semiconductors are dominated by excitons (bound electron-hole, e-h, pairs) with binding energies of hundreds of meV1, with spin and valley properties (such as valley-selective circular dichroism2) highly beneficial for optoelectronics2, valleytronics3 and spintronics3–12. Following optical excitation of a semiconductor above the band gap, the subsequent energy relaxation pathways play an important role in optics13–15 and charge carrier transport16,17. These processes are related to hot (i.e. not in thermal equilibrium) charge carriers and excitons1, and determine electron mobility18, optical absorption in indirect band gap semiconductors19, and intervalley scattering of hot electrons19. Photoluminescence (PL) and Raman scattering can be used to probe the interactions of carriers with phonons20. Different types of phonons with different energies can participate in the relaxation process of excited carriers. However, in some materials one type of phonon plays a dominant role and leads to high-order processes, e.g. up to nine longitudinal optical (LO) phonon replicas were reported in the hot PL of CdS and CdSe20–22. Multiphonon processes are important in defining the optoelectronic performance of ZnO23–26, GaN27 and bulk MoS228. The optical oscillator strength in 1L-TMDs, i.e. the probability of optical transitions between valence and conduction states, is higher than in III-V quantum wells19, resulting in short (~1ps29) exciton lifetimes. This favors hot PL emission, as excitons relax between several real states30,31. Examination of phonon-induced cascade-like relaxation processes in 1L-TMDs has been proposed for future pump-probe experiments32. However, observation of direct optical signatures in the early stages of carrier relaxation still remains a significant challenge, because of the ultrafast timescale (~100fs33) of these processes. Understanding the relaxation pathways in tungsten diselenide monolayers (1L-WSe2) is important for optoelectronic applications, such as photodetectors34 and lasers35, because it determines the recovery rate (i.e. the population of carriers relaxing to the ground state over time) and, as a result, the devices’ speed and efficiency.

Here, we use ultra-low (~5 cm−1 ~0.6 meV) cut-off frequency (ULF) Raman spectroscopy to investigate the light scattered and emitted by 1L-WSe2 on SiO2, hBN and Au, as well as suspended 1L-WSe2. We observe phonon-assisted emission of hot PL, periodic in energy both in the Stokes (S) and anti-Stokes (AS) spectral range, and we extract a phonon energy ~15 meV. The S signal shows 7 maxima in the range of temperatures (T) from 78 to 295 K. We also detect up to 5 maxima in the AS signal ~75 meV above the laser excitation energy, increasing in intensity as T is raised. We assign these to phonon cascades36. We include finite T effects to compare S and AS signals and to understand carrier relaxation at room temperature (RT). By analyzing the T and excitation energy dependence, we conclude that a continuum of states (in the free-carrier gap) is involved in e-h relaxation in 1L-WSe2. Intermediate states in the conduction band around the Λ-valley of the Brillouin zone (BZ) participate in the cascade process. Hot PL so close in energy to the excitation laser gives access to the initial stages of carrier relaxation. These processes are ultrafast (e.g. ~100fs in GaAs33) and it is therefore challenging to access them in time-resolved experiments. Our approach can be extended to all layered materials (LMs) and their heterostructures (LMHs), as well as to other materials systems, such as perovskites37,38.

Results

1L-WSe2 flakes are exfoliated from bulk 2H-WSe2 crystals (2D Semiconductors) by micromechanical cleavage on Nitto Denko tape39, then exfoliated again on a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) stamp placed on a glass slide for inspection under optical microscope. Optical contrast is used to identify 1L prior to transfer40. Before transfer, 85 nm (for optimum contrast40) SiO2/Si substrates are wet cleaned41 (60s long ultrasonication in acetone and isopropanol) and subsequently exposed to oxygen-assisted plasma at 10W for 60s. The 1L-WSe2 flakes are then stamped on the substrate with a micro-manipulator at 40 °C, before increasing T up to 60 °C to release 1L-WSe242. The same procedure is followed for transfer of 1L-WSe2 on hBN, Au and Si, with 2 μm Au trenches made by lithography, to suspend the samples.

The Raman and hot PL spectra are recorded in a back-reflection geometry with a ×50 objective (NA = 0.45) and a spot size ~1 μm. A liquid nitrogen cryostat (Linkam Scientific) placed on a XY translational stage is used to control T between 78 K and 295 K and excitation area. Imaging of the sample and monitoring of the excitation spot position are achieved using a set of beam splitters, aligned to a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera. The PL and Raman signals collected in the backward direction are filtered by 3 notch volume Bragg filters with a total optical density (OD) = 9. The cut-off frequency is ~5 cm−1 (~0.6 meV). The filtered signals are then focused on the spectrometer slit and dispersed by a 1800l/mm grating before being collected by the detector.

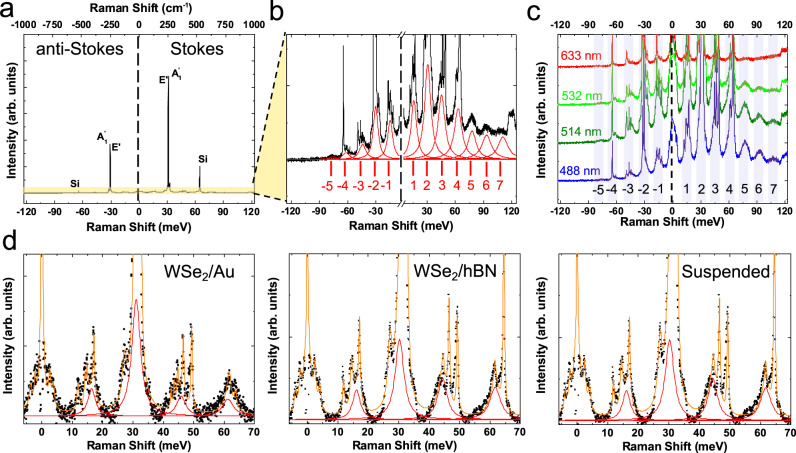

A typical RT Raman spectrum for 1L-WSe2 on SiO2/Si measured at 532 nm is shown in Fig. 1a. The degenerate in-plane, , and out-of-plane,

Raman and hot PL spectra of 1L-WSe2.

a Emission and scattering spectrum of 1L-WSe2 at 295K as a function of energy shift with respect to the excitation laser (532 nm~2.33eV). The degenerate in-plane (

To exclude the possibility that our laser is in resonance with a specific transition, we perform variable excitation wavelength experiments at 295K. Figure 1c plots the spectra measured at 488 nm (~2.54 eV), 514 nm (~2.41 eV), 532 nm (~2.33 eV) and 633 nm (~1.96 eV). We observe the same high-order features with identical energy separations in both S and AS. All these excitation energies lie above the free-carrier gap of 1L-WSe2 ~ 1.89 eV49–51. By comparing results for 1L-WSe2 on different substrates and for different excitation energies, we deduce that phonon-assisted hot PL is the dominant mechanism, whereas contributions from other excitations, such as plasmons52, are negligible, otherwise intensity and/or energy variations would be expected between Au and SiO2/Si, hBN, suspended cases.

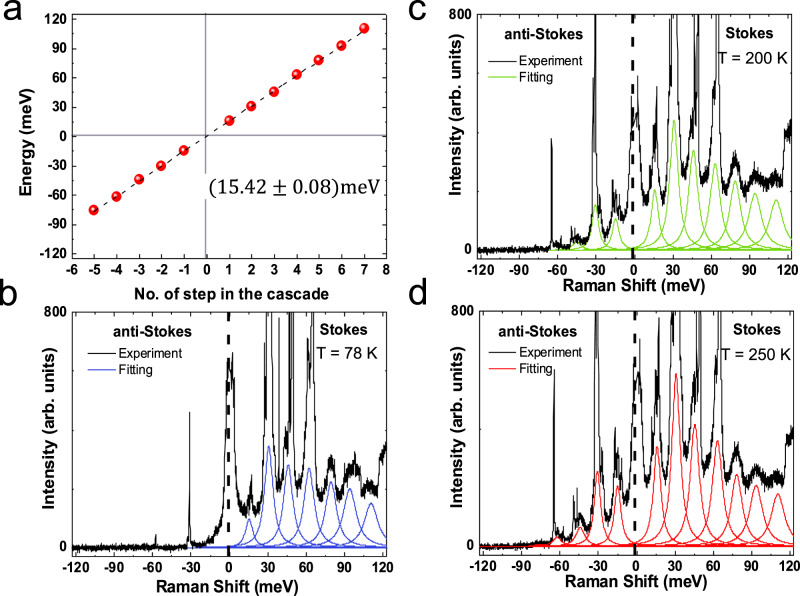

Figure 2a plots the energy offset with respect to the excitation laser (here 532 nm) of each emission feature as a function of the number of steps in the cascade at 295 K. Applying a linear fit, we extract ~15.42 ± 0.08 meV, regardless of substrate and excitation energy. This periodic modulation of the detected light intensity suggests that the scattering of photoexcited carriers is dominated by one prominent phonon mode. Since we excite above the free-carrier gap of 1L-WSe249, the intermediate states of the transitions are real. The e-h pair representation is in Fig. 3a.

Energy separation and T dependence.

a Emission energies as a function of number of steps in the cascade, extracted from the RT spectrum in Fig. 1b. The dashed black line is a linear fit, giving a step energy ~15.42 ± 0.08meV. b–d 532 nm Hot PL spectra of 1L-WSe2 at b 78 K, c 200 K, d 250 K.

Comparison between experiments and theory.

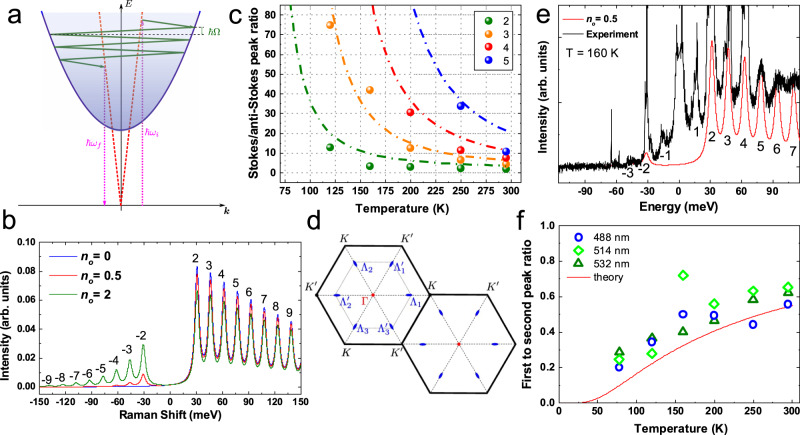

a Scheme of phonon-assisted hot PL. The incident,

The lattice T could affect the peaks intensity, as phonon occupation increases with T53,54. We thus perform T dependent measurements from 78 to 295 K, while keeping the excitation power constant ~26 μW. No emission of AS features is observed at 78 K, Fig. 2b, with the exception of two sharp lines ~−30 and ~−60 meV, originating from 1L-WSe2 and Si Raman modes, respectively. The hot PL peaks are seen at 200 K, Fig. 2c, and a further increase in intensity is observed at 250 K, Fig. 2d. Additional measurements at 120, 160, and 295 K are performed and used in the fits in Fig. 3c. Thermal effects are expected to modify the phonon energies55. However, in the 78–298 K range we do not observe any measurable shifts in the position of the hot PL peaks, because the shifts induced by acoustic phonons are smaller compared to our experimental error, as discussed in Methods.

Discussion

At low T (78 K), phonon absorption processes are suppressed because of the insufficient lattice thermal energy53. Optical excitation results in free e-h pair formation56,57 or virtual formation of an exciton with small in-plane wavevector (k ≲ ωi/c with ωi the excitation laser frequency)1. With the subsequent phonon emission, the e-h pair reaches a real final state (blue parabola in Fig. 3a), for which radiative recombination is forbidden by momentum conservation19. This triggers a cascade relaxation process36, whereby at each step a phonon is emitted (or absorbed for a T whereby the thermal energy is equal or higher than the phonon one energy)19. If the interaction with one phonon mode with energy ℏΩ dominates overall other inelastic scattering processes, the exciton loses energy by integer multiples of ℏΩ19,36. After emission of several (≥2) phonons, the exciton recombines and emits a photon with frequency ωf in a two-step process via an intermediate state with a small (k ≲ ωi/c) wavevector, for which radiative recombination is momentum allowed. Thus, we have secondary emission or scattering of light with S shift ωi − ωf = jΩ, where j = 2, 3, …., while j = ±1 are impossible as we scatter out of the light cone (i.e. the region of small wavevectors) with the first event. At finite T, in addition to phonon emission, absorption also comes into play, and AS emission is observed at ωf − ωi = jΩ.

Multiphonon processes that do not involve real states require higher order exciton–phonon interactions58, and are therefore less probable. In contrast, the process in Fig. 1c is resonant, since excitation in the free-carrier gap means that all intermediate states are real. This allows us to describe the phonon emission cascade via the kinetic equation for the exciton distribution function f(ε), where ε is the exciton energy, as derived in Supplementary Notes 2, 3. Since the energy of the exciton changes in each scattering event by ±ℏΩ, the distribution function can be written as:

The general solution of Eq. (2) is:

The calculated I distribution and spectra at various T (corresponding to different no) are presented in Fig. 3b. Figure 3c plots IS/IAS as a function of T from Eq. (9). The experimental points collected from the fitted I of each step in the cascade at 532 nm excitation are displayed with circles. The absence of data at 78 K indicates no detection of IAS at this T. Applying Eq. (9) to the steps 2–5 in the cascade, with a phonon energy ~15.4 meV extracted from Fig. 2a, gives the dashed lines in Fig. 3c, in good agreement with experiments.

Our model captures the main experimental observations well. The periodic pattern of hot PL intensity is reproduced by the calculations, Fig. 3b, and IS/IAS closely follows Eqs. (9), Fig. 3c. There is good agreement between our data and the calculated spectra from Eq. (2). An example for no = 0.5 at 160 K is in Fig. 3e. In our model, the peaks with j = ±1 are absent because N ≥ 2 phonons are needed for the first step of the cascade process, as for Fig. 3a. However, Fig. 1 shows that j = ±1 peaks are smaller than j = ±2 ones, but still detectable. We consider IS(1)/IS(2) as plotted in Fig. 3f. The possible mechanisms of j = 1 peak formation are as follows. (i) Elastic disorder or acoustic phonon-induced scattering, which provides a transfer between states within the light cone and states at the dispersion. (ii) Combination of phonon emission and absorption, where the j = 1 peak appears as a result of two phonon emission, followed by one phonon absorption. In (i) IS(1)/IS(2) does not depend on T. In (ii):

To get a better understanding of the relaxation pathways, we consider different scattering mechanisms. Scattering within the same valley is not plausible, due to the mismatch of BZ centre phonon energies61. The energy ~15 meV could correspond to either Γ − K or Γ − Λ phonons. The phonon dispersion in 1L-WSe2 shows acoustic phonons with energies ~15 meV46,61. These have a flat dispersion, necessary to observe the high number of oscillations we report, and are compatible with the model in Fig. 3a.

Another option involves K-

Similar oscillations can appear for free e and h36, see Supplementary Note 4. The basic description of the effect is similar to what we observe here, and our model can be extended to take into account e/h distribution functions. The spectra of scattered light and IS/IAS are similar to those calculated above. We cannot distinguish between exciton and the free-carrier cascades directly in our experiments. The excitonic description, however, seems straightforward due to enhanced (with respect to bulk materials) Coulomb effects in 1L-TMDs1.

In conclusion, we investigated the light scattered and emitted by 1L-WSe2 excited above the free-carrier gap. We detected a periodic modulation of phonon-assisted hot PL with a period ~15 meV both in S and AS. We measured the S and AS intensity evolution from 78 to 295 K. We explained these high-order processes using a cascade model where electrons (holes) make successive transitions between real states with a finite probability of radiative recombination at each step. The electron states in the Λ valleys are intermediate states for efficient exciton relaxation. Our findings provide fundamental understanding of the initial steps of exciton relaxation in 1L-WSe2, and can be used to design optoelectronic devices based on this material. Our approach can be extended also to other layered materials and their heterostructures, as well as to perovskites.

Methods

Raman and PL spectra fitting

Supplementary Fig. 1a–c presents optical microscopy images of representative samples: (a) 1L-WSe2 on Au and suspended 1L-WSe2; (b) 1L-WSe2 on SiO2/Si; (c) 1L-WSe2 on hBN. Representative PL spectra collected 295 K at 514 nm excitation are in Supplementary Fig. 1d, showing a peak ~1.65 eV related to the A-exciton resonance1,12. Supplementary Fig. 2a shows representative data fits. The spectrum, at 295 K for 532 nm excitation, is shown with black dots. Blue lorentzian functions are used to fit the Raman peaks (FWHM ~ 1–10 cm−1). The residual spectral weight is also fitted with Lorentzians and results into the broader (FWHM ~ 50–80 cm−1) peaks of the hot PL (red). A flat baseline is taken into account for the whole energy scale, since the background in the S spectral range increases due to the higher intensity of the S cascades compared to the AS ones. A fit is shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b. The Lorentzians overlap, creating an asymmetric broad background (indicated by yellow dashed lines in Supplementary Fig. 2b).

We now consider the thermally induced shift in the hot PL cascades of 1L-WSe2 in the 78–295 K range. We analyze Pos(E

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20244-7.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from ANR 2D-vdW-Spin, ANR MagicValley, the Institut Universitaire de France, the RFBR and CNRS joint project 20-52-16303, EU Graphene Flagship, ERC Grants Hetero2D and GSYNCOR, EPSRC Grants EP/K01711X/1, EP/ K017144/1, EP/N010345/1, EP/L016087/1. G.W. acknowledges the support from the National Science Foundation of China Grant No. 11904019 and Beijing Natural Science Foundation Grant No. Z190006.

Author contributions

B.U., M.M.G., X.M., I.P. and A.C.F. conceived the project. I.P. and G.W. performed the experiments and acquired the data. I.P. analysed the results. I.P., E.M.A. and A.R.C. fabricated the samples. M.M.G. performed the theoretical studies. I.P., M.M.G., B.U., X.M. and A.C.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

Efficient phonon cascades in WSe2 monolayers

Efficient phonon cascades in WSe2 monolayers