The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

FST and kinship are key parameters often estimated in modern population genetics studies in order to quantitatively characterize structure and relatedness. Kinship matrices have also become a fundamental quantity used in genome-wide association studies and heritability estimation. The most frequently-used estimators of FST and kinship are method-of-moments estimators whose accuracies depend strongly on the existence of simple underlying forms of structure, such as the independent subpopulations model of non-overlapping, independently evolving subpopulations. However, modern data sets have revealed that these simple models of structure likely do not hold in many populations, including humans. In this work, we analyze the behavior of these estimators in the presence of arbitrarily-complex population structures, which results in an improved estimation framework specifically designed for arbitrary population structures. After generalizing the definition of FST to arbitrary population structures and establishing a framework for assessing bias and consistency of genome-wide estimators, we calculate the accuracy of existing FST and kinship estimators under arbitrary population structures, characterizing biases and estimation challenges unobserved under their originally-assumed models of structure. We then present our new approach, which consistently estimates kinship and FST when the minimum kinship value in the dataset is estimated consistently. We illustrate our results using simulated genotypes from an admixture model, constructing a one-dimensional geographic scenario that departs nontrivially from the independent subpopulations model. Our simulations reveal the potential for severe biases in estimates of existing approaches that are overcome by our new framework. This work may significantly improve future analyses that rely on accurate kinship and FST estimates.

Kinship coefficients and FST, which measure relatedness and population structure, respectively, are important quantities needed to accurately perform various analyses on genetic data, including genome-wide association studies and heritability estimation. However, existing estimators require restrictive assumptions of independence that are not met by real human and other datasets. In this work we find that existing estimators can be severely biased under reasonable scenarios, first by theoretically determining their properties, and then using an admixture simulation to illustrate our findings. In particular, we find that existing FST estimators are downwardly biased, and that existing kinship matrix estimators have related biases that are on average downward and of similar magnitude but vary for every pair of individuals. These insights led us to a new estimation framework for kinship and FST that is practically unbiased for any population structure, as demonstrated by theory and simulations. Our new approaches—available as open-source R packages—are easy to use and are more widely applicable than existing approaches, and they are likely to improve downstream analyses that require accurate kinship and FST estimates.

Introduction

In population genetics studies, one is often interested in characterizing structure, genetic differentiation, and relatedness among individuals. Two quantities often considered in this context are FST and kinship. FST is a parameter that measures structure in a subdivided population, satisfying FST = 0 for an unstructured population and FST = 1 if every locus has become fixed for some allele in each subpopulation. More generally, FST is the probability that alleles drawn randomly from a subpopulation are “identical by descent” (IBD) relative to an ancestral population [1, 2]. The kinship coefficient is a measure of relatedness between individuals defined in terms of IBD probabilities, and it is closely related to FST, since the mean kinship of the parents in a subpopulation is the FST of the following generation [1].

This work focuses on the estimation of FST and kinship from biallelic single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data. Existing estimators can be classified into parametric estimators (methods that require a likelihood function) and non-parametric estimators (such as the method-of-moments estimators we focus on, which only require low-order moment equations). There are many likelihood approaches that estimate FST and kinship, but these are limited by assuming independent subpopulations or Normal approximations for FST [3–11] or totally outbred individuals for kinship [12, 13]. Additionally, more complete likelihood models such as that of Jacquard [14] are underdetermined for biallelic loci [15]. Non-parametric approaches such as those based on the method of moments are considerably more flexible and computationally tractable [16], so they are the natural choice to study arbitrary population structures.

The most frequently-used FST estimators are derived and justified under the “independent subpopulations model,” in which non-overlapping subpopulations evolved independently by splitting all at the same time from a common ancestral population. The Weir-Cockerham (WC) FST estimator assumes subpopulations of differing sample sizes and equal per-subpopulation FST relative to the common ancestral population [17]. The Weir-Hill FST estimator generalized WC for subpopulations with different FST values, and first considered arbitrary coancestry between subpopulations, resulting in estimates of a linearly-transformed FST, namely (where

Kinship coefficients are now commonly calculated in population genetics studies to capture structure and relatedness. Kinship is utilized in principal components analyses and linear-mixed effects models to correct for structure in Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) [16, 24–30] and to estimate genome-wide heritability [31, 32]. Often absent in previous models is a clear identification and role of the ancestral population T that sets the scale of the kinship estimates used. Omission of T makes sense when kinship is estimated on an unstructured population (where only a few individual pairs are closely related; there T is the current population). Our more complete notation brings T to the fore and highlights its key role in kinship estimation and its applications. The most commonly-used kinship estimator [16, 27, 30–36] is also a method-of-moments estimator whose operating characteristics are largely unknown in the presence of structure. We show here that this popular estimator is accurate only when the average kinship is zero, which implies that the population must be unstructured.

The goal of our work is to consistently estimate IBD probabilities, namely kinship coefficients and FST, for which there are currently no consistent estimators under general relatedness. Estimation of these as probabilities, as opposed to linearly-transformed quantities that may be negative, is important since the probabilistic definition of these parameters was required to derive their fundamental connections to many applications in genetics, including allele fixation [1, 2, 37], DNA forensics [3], and heritability [38, 39]. Although IBD probabilities are not absolute, but rather depend on the choice of ancestral population [40], their values become fixed upon agreeing to estimate them in terms of the Most Recent Common Ancestor (MRCA) population, which has long been the choice for models of FST [17, 23, 41] and kinship estimation from pedigrees [42, 43] or markers [12, 13].

Recent genome-wide studies have revealed that humans and other natural populations are structured in a complex manner that break the assumptions of the above estimators. Such complex population structures has been observed in several large human studies, such as the Human Genome Diversity Project [44, 45], the 1000 Genomes Project [46], Human Origins [47–49], and other contemporary [50–54] and archaic populations [55, 56]. We have also demonstrated that the global human population has a complex kinship matrix and no independent subpopulations [57–59]. Therefore, there is a need for innovative approaches designed for complex population structures. To this end, we reveal the operating characteristics of these frequently-used FST and kinship estimators in the presence of arbitrary forms of structure, which leads to a new estimation strategy for FST and kinship.

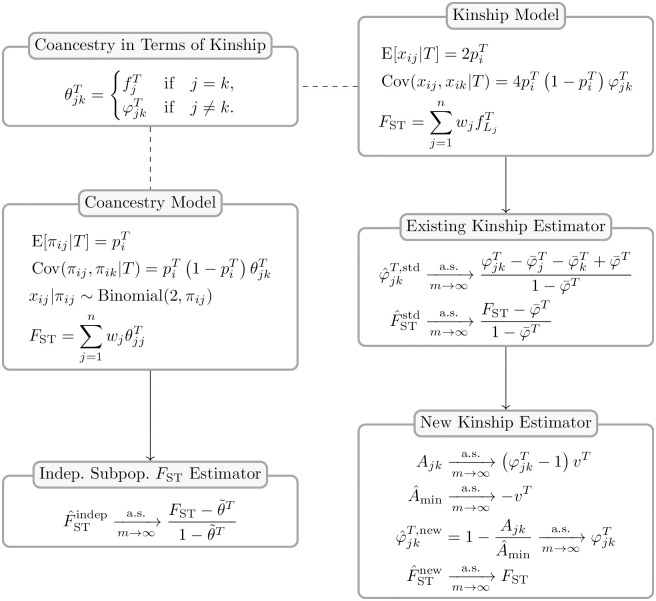

Here, we study existing FST and kinship method-of-moments estimators in models that allow for arbitrary population structures (see Fig 1 for an overview of the results). First, in section The generalized FST for arbitrary population structures we present the generalized definition of FST for arbitrary population structures [57]. In section The kinship and coancestry models we review the kinship model for genotype covariance [1, 14] and the coancestry model for individual-specific allele frequencies [57, 60, 61]. In section Assessing the accuracy of genome-wide ratio estimators we obtain new strong convergence results for a family of ratio estimators that includes the most common FST and kinship estimators. Next, we calculate the convergence values of these FST (section FST estimation based on the independent subpopulations model) and kinship (section Characterizing a kinship estimator and its relationship to FST) estimators under arbitrary population structures, where we find biases that are not present under their original assumptions about structure (panels “Indep. Subpop. FST Estimator” and “Existing Kinship Estimator” in Fig 1). We characterize the limit of the standard kinship estimator, identifying complex biases or distortions, in agreement with recent work [21, 62].

Accuracy of FST and kinship estimators: Overview of models and results.

Our analysis is based on the generalized FST definition (section The generalized FST for arbitrary population structures) and two parallel models: the “Coancestry Model” for individual-specific allele frequencies (πij), and the “Kinship Model” for genotypes (xij). The “Coancestry in Terms of Kinship” panel connects kinship (

In section A new approach for kinship and FST estimation we introduce a new approach for kinship and FST estimation for arbitrary population structures, and demonstrate the improved performance using a simple implementation of these estimators (panel “New Kinship Estimator” in Fig 1). There are two key innovations. First, based on the method of moments, we derive a statistic that estimates kinship coefficients up to a shared unknown scaling factor. Second, we propose a new condition, the identification of unrelated individual pairs in the data, which yields the value of the unknown scaling factor and enables the consistent estimation of kinship matrices and FST. We present a simple implementation of this second estimator, based on taking the minimum average statistic value between subpopulations, which in section Simulations evaluating FST and kinship estimators is shown to perform well under some misspecification, namely in an admixture scenario that does not actually have subpopulations [63–65]. Elsewhere, we analyze the Human Origins and 1000 Genomes Project datasets with our novel kinship and FST estimation approach, where we demonstrate its coherence with the African Origins model, and illustrate the shortcomings of previous approaches in these complex data [59]. In summary, we identify a new approach for unbiased estimation of FST and kinship, and we provide new estimators that are nearly unbiased.

Results

The generalized FST for arbitrary population structures

The existing FST definition requires individuals to belong to discrete, non-overlapping subpopulations, so it must be generalized in order to apply to arbitrary population structures (such as the admixture model with individual-specific ancestry proportions considered in our simulations). Our generalized FST can be understood as a two-step strategy: (1) we define FST on a per-individual basis, and (2) we define FST for a group of individuals as a weighted average of the per-individual FST values [57].

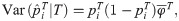

The inbreeding coefficient

Now we discuss estimating the three quantities we just introduced. First, the total inbreeding coefficient (

As a toy example, suppose we estimate a total inbreeding coefficient of

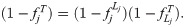

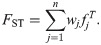

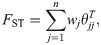

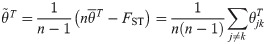

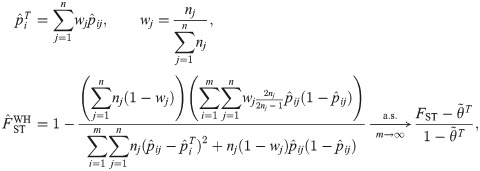

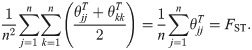

We define the generalized FST across n individuals as the weighted average of the per-individual structural inbreeding coefficients (i.e., individual FST values) [57],

In terms of total and local inbreeding coefficients (using Eq (2)), the generalized FST equals

The kinship and coancestry models

The generalized FST above is given solely in terms of inbreeding coefficients. In order to establish our results and framework, it is necessary to consider kinship coefficients as well. The kinship coefficient is the extension of the inbreeding coefficient for a pair of individuals: the kinship coefficient

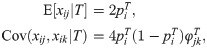

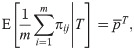

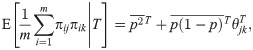

Kinship coefficients determine the covariance structure of genotypes, which is the key to estimating kinship and FST from genotype data. We shall concentrate on biallelic variants, which include single-nucleotide polymorphisms, and are the dominant data from genotyping microarrays and whole-genome sequencing studies. We shall also restrict our attention to diploid organisms in this present work. Genotypes are encoded into variables xij for each locus i and individual j that count the number of alleles (dosage) of a given reference type, so for diploid organisms xij = 2 is homozygous for the reference allele, xij = 0 is homozygous for the alternative allele, and xij = 1 is heterozygous. Based on the definition of the IBD probabilities, the kinship model determines the mean and covariance structure of the genotype random variables at neutral loci [1, 2, 14, 16, 37]:

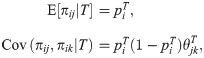

The coancestry model resembles the kinship model, but it is formulated in terms of allele frequencies, which simplifies our analysis of FST estimators for subpopulations as well as yielding kinship coefficients under the admixture model we simulate from in this work. Let πij be the individual-specific allele frequency (IAF) at locus i for individual j, which is a real number between zero and one [60, 61]. Our coancestry model assumes that [57]

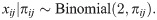

The coancestry model connects to the kinship model under the additional assumption that the alleles of an individual j are drawn independently from its IAF,

Assessing the accuracy of genome-wide ratio estimators

In this section we change gears to focus on theoretical convergence properties of two broad estimator families. The resulting theory will be applied repeatedly to various FST and kinship estimators of interest in later sections.

Many FST and kinship coefficient method-of-moments estimators are ratio estimators, a general class of estimators that tends to be biased and to have no closed-form expectation [69]. In the FST literature, the expectation of a ratio is frequently approximated with a ratio of expectations [4, 17, 23]. Specifically, ratio estimators are often called “unbiased” if the ratio of expectations is unbiased, even though the ratio estimator itself may be biased [69]. Here we characterize the behavior of two ratio estimator families calculated from genome-wide data, known as “ratio-of-means” and “mean-of-ratios” estimators [23], detailing conditions where the previous approximation is justified and providing additional criteria to assess the accuracy of such estimators.

Ratio estimators

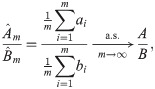

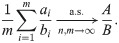

The general problem of forming ratio estimators involves random variables ai and bi calculated from genotypes at each locus i, such that E[ai] = Aci and E[bi] = Bci and the goal is to estimate

Convergence

The solution we recommend is the “ratio-of-means” estimator

In order to test if a given ratio-of-means estimator converges to its ratio of expectations as in Eq (10), the following three conditions can be tested. (i) The expected values of each term ai, bi must be calculated and shown to be of the form E[ai] = Aci and E[bi] = Bci for some A and B shared by all loci i and some ci that may vary per locus i but must be shared by both E[ai], E[bi]. In the estimators we study, A and B are functions of IBD probabilities such as

Another approach is the “mean-of-ratios” estimator

FST estimation based on the independent subpopulations model

Now that we have detailed how ratio estimators may be evaluated for their accuracy, we turn to existing estimators and assess their accuracy under arbitrary population structures. We study the FST estimators Weir-Cockerham (WC) [17], Weir-Hill [4], “Hudson” [23], and Weir-Goudet (equals HudsonK below for biallelic loci; S1 Text) [21]. The panel “Indep. Subpop. FST Estimator” in Fig 1 provides an overview of our results, which we detail in this section.

The FST estimator for independent subpopulations and infinite subpopulation sample sizes

The WC, Weir-Hill, and Hudson method-of-moments estimators have small sample size corrections that remarkably make them consistent (as the number of independent loci m goes to infinity) for finite numbers of individuals. However, these small sample corrections also make the estimators unnecessarily cumbersome for our purposes (see Methods, section Previous FST estimators for the independent subpopulations model for complete formulas). In order to illustrate clearly how these estimators behave, both under the independent subpopulations model and for arbitrary structure, here we construct simplified versions that assume infinite sample sizes per subpopulation (Methods, section Previous FST estimators for the independent subpopulations model). This simplification corresponds to eliminating statistical sampling, leaving only genetic sampling to analyze [71]. Note that our simplified estimator nevertheless illustrates the general behavior of the WC, Weir-Hill, and Hudson estimators under arbitrary structure, and the results are equivalent to those we would obtain under finite sample sizes of individuals. While the Hudson FST estimator compares two subpopulations [23], based on that work we derive a generalized “HudsonK” estimator for more than two subpopulations in Methods, section Generalized HudsonK FST estimator. Note that HudsonK, first derived in [58], also equals the Weir-Goudet FST estimator for subpopulations [21] when loci are biallelic, which was derived independently using allele matching (S1 Text).

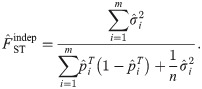

Under infinite subpopulation sample sizes, the allele frequencies at each locus and every subpopulation are known. Let j ∈ {1, …, n} index subpopulations rather than individuals and πij be the true allele frequency in subpopulation j at locus i. Note that πij are not estimated allele frequencies, but rather true subpopulation allele frequencies; this abstraction does not result in a practical estimation approach, but it greatly simplifies understanding of bias for subpopulations in a setting where there there is no statistical sampling. Although in this analysis of FST estimators the πij values are applied to subpopulations, for coherence with our previous work we shall call them “individual-specific allele frequencies” (IAF) [60, 61]. Whether for individuals or subpopulations, the key assumption is that IAFs satisfy the coancestry model of Eq (6). In this special case of infinite subpopulation sample sizes, all of WC, Weir-Hill, and HudsonK simplify to the following FST estimator for independent subpopulations (“indep”; derived in Methods, section Previous FST estimators for the independent subpopulations model):

FST estimation under the independent subpopulations model

Under the independent subpopulations model

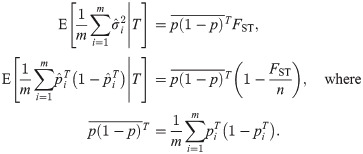

Before applying the convergence result in Eq (10), we test that the three conditions listed in section Assessing the accuracy of genome-wide ratio estimators are met. Condition (i): The locus i terms are

FST estimation under arbitrary coancestry

Now we consider applying the independent subpopulations FST estimator to dependent subpopulations. The key difference is that now

The FST estimator for independent subpopulations converges more generally to

Since

Coancestry estimation as a method of moments

Since the generalized FST is given by coancestry coefficients

Given IAFs and the coancestry model of Eq (6), the first and second moments that average across loci are

Suppose first that only

Characterizing a kinship estimator and its relationship to FST

Given the biases we see for

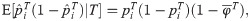

In this section, we focus on a standard kinship method-of-moments estimator and calculate its limit for the first time (panel “Existing Kinship Estimator” in Fig 1). We study estimators that use genotypes or IAFs, and construct FST estimators from their kinship estimates. We find biases comparable to those of

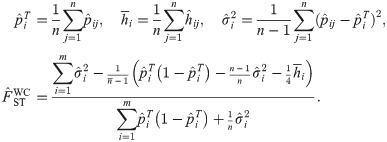

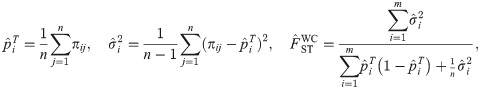

Characterization of the standard kinship estimator

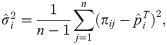

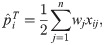

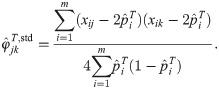

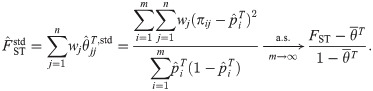

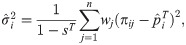

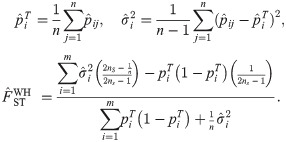

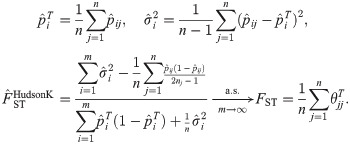

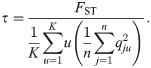

Here we analyze a standard kinship estimator that is frequently used [16, 27, 30–36]. We generalize this estimator to use weights in estimating the ancestral allele frequencies, and we write it as a ratio-of-means estimator due to the favorable theoretical properties of this format as detailed in the earlier section Assessing the accuracy of genome-wide ratio estimators:

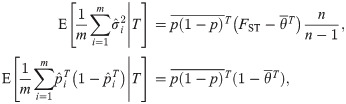

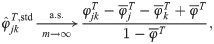

Utilizing the kinship model for genotypes from Eq (5), we find that Eq (18) converges to

The estimators in Eqs (18) and (21) are unbiased when

Estimation of coancestry coefficients from IAFs

Here we form a coancestry coefficient estimator analogous to Eq (18) but using IAFs. Assuming the moments in Eq (6), this estimator and its limit are

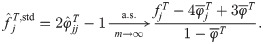

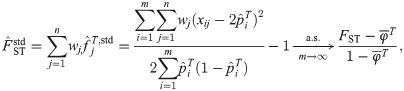

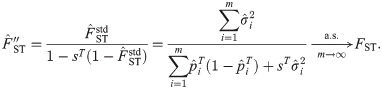

FST estimator based on the standard kinship estimator

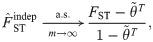

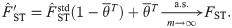

Since the generalized FST is defined as a mean inbreeding coefficient in Eq (3), here we study the FST estimator constructed as

Remarkably, the three

Like

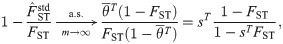

Adjusted consistent oracle FST estimators and the “bias coefficient”

Here we explore two adjustments to

If

Lastly, using either Eqs (26) or (29), the relative error of

A new approach for kinship and FST estimation

Here, we propose a new estimation approach for kinship coefficients that has properties favorable for obtaining nearly unbiased estimates (panel “New Kinship Estimator” in Fig 1). These new kinship estimates yield an improved FST estimator. We present the general approach and implement a simple version of one key estimator that results in the complete proof-of-principle estimator that is evaluated in the next section and applied to human data in [59]. We also compare our approach to a related estimator of non-IBD linearly-transformed kinship values [20–22] that was proposed concurrently to ours [58].

General approach

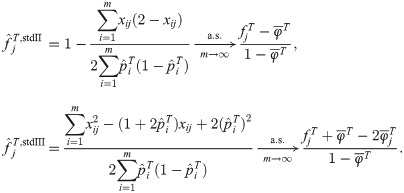

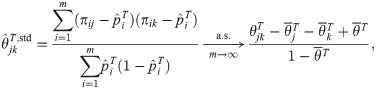

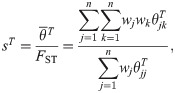

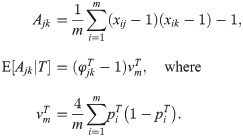

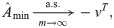

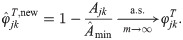

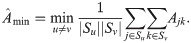

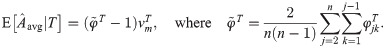

In this subsection we develop our new estimator in two steps. First, we compute a new statistic Ajk that is proportional in the limit of infinite loci to

Applying the method of moments to Eq (5), we derive the following statistic (S1 Text), whose expectation is proportional to

In general, suppose

Proof-of-principle kinship estimator using subpopulation labels

To showcase the potential of the new estimators, we implement a simple proof-of-principle version of

This estimator should work well for individuals truly divided into subpopulations, but may be biased for a poor choice of subpopulations, in particular if the minimum mean

Comparison to the Weir-Goudet kinship estimator for individuals

Here we analyze the Weir-Goudet (WG) kinship estimator for individuals [20–22]. This has connections to our new estimator but differs in having the goal of estimating linearly-transformed kinship values. In our framework, the WG estimator is given by

Note that the original WG does not estimate FST from individuals as considered above; instead, FST is estimated from coancestry estimates for subpopulations (which equals our HudsonK for biallelic loci, S1 Text) [20–22]. For completeness, we consider both kinds of FST estimates in the evaluations that follow.

Simulations evaluating FST and kinship estimators

Overview of simulations

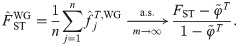

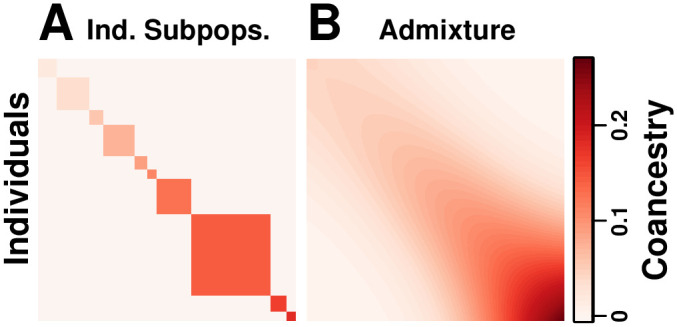

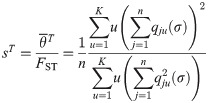

We simulate genotypes from two models to illustrate our results when the true population structure parameters are known. Both simulations have clearly-defined IBD probability parameters in terms of the MRCA population. The first simulation satisfies the independent subpopulations model that existing FST estimators assume. The second simulation is from an admixture model with no independent subpopulations and pervasive kinship designed to induce large downward biases in existing kinship and FST estimators (Fig 2). This admixture scenario resembles the population structure we estimated for Hispanics in the 1000 Genomes Project [59]: compare the simulated kinship matrix (Fig 2B) and admixture proportions (Fig 3C) to our estimates on the real data [59]. Both simulations have n = 1000 individuals, m = 300, 000 loci, and K = 10 subpopulations or intermediate subpopulations. These simulations have FST = 0.1, comparable to previous estimates between human populations (in 1000 Genomes, the estimated FST between CEU (European-Americans) and CHB (Chinese) is 0.106, between CEU and YRI (Yoruba from Nigeria) it is 0.139, and between CHB and YRI it is 0.161 [23]).

Coancestry matrices of simulations.

Both panels have n = 1000 individuals along both axes, K = 10 subpopulations (final or intermediate), and FST = 0.1. Color corresponds to

1D admixture scenario.

We model a 1D geography population that departs strongly from the independent subpopulations model. (A) K = 10 intermediate subpopulations, evenly spaced on a line, evolved independently in the past with FST increasing with distance, which models a sequence of increasing founder effects (from left to right) to mimic the global human population. (B) Once differentiated, individuals in these intermediate subpopulations spread by random walk modeled by Normal densities. (C) n = 1000 individuals, sampled evenly in the same geographical range, are admixed proportionally to the previous Normal densities. Thus, each individual draws most of its alleles from the closest intermediate subpopulation, and draws the fewest alleles from the most distant populations. Long-distance random walks of intermediate subpopulation individuals results in kinship for admixed individuals that decays smoothly with distance in Fig 2B. (D) For FST estimators that require a partition of individuals into subpopulations, individuals are clustered by geographical position (K = 10).

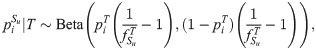

The independent subpopulations simulation satisfies the HudsonK and BayeScan estimator assumptions: each independent subpopulation Su has a different FST value of

The admixture simulation corresponds to a “BN-PSD” model [6, 27, 34, 60, 77]: the intermediate subpopulations are independent subpopulations that draw

Evaluation of FST estimators

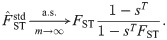

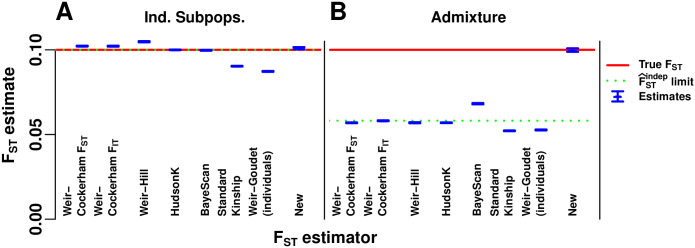

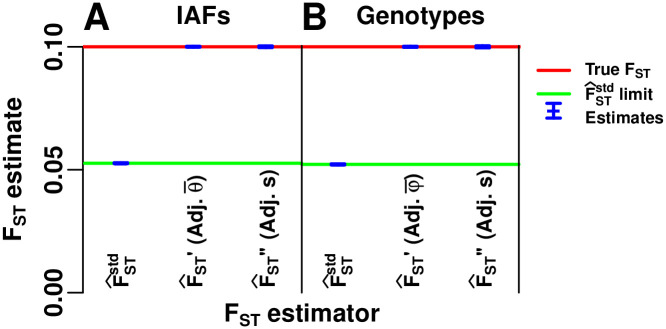

Our admixture simulation illustrates the large biases that can arise if existing FST estimators that require independent subpopulations or FST estimates derived from existing kinship estimators are misapplied to arbitrary population structures to estimate the generalized FST, and demonstrate the higher accuracy of our new FST estimator (

First, we test these estimators in our independent subpopulations simulation. The HudsonK (Methods, section Generalized HudsonK FST estimator) and BayeScan FST estimators are consistent in this simulation, since their assumptions are satisfied (Fig 4A). The WC FST estimator assumes that

Evaluation of FST estimators.

The Weir-Cockerham, Weir-Hill, Weir-Goudet (for individuals), HudsonK (equal to Weir-Goudet for subpopulations, S1 Text), BayeScan,

Next we test these estimators in our admixture simulation. To apply the FST estimators that require subpopulations to the admixture model, individuals are clustered into subpopulations by their geographical position (Fig 3D). We find that estimates of all existing methods are smaller than the true FST by nearly half, as predicted by the limit of

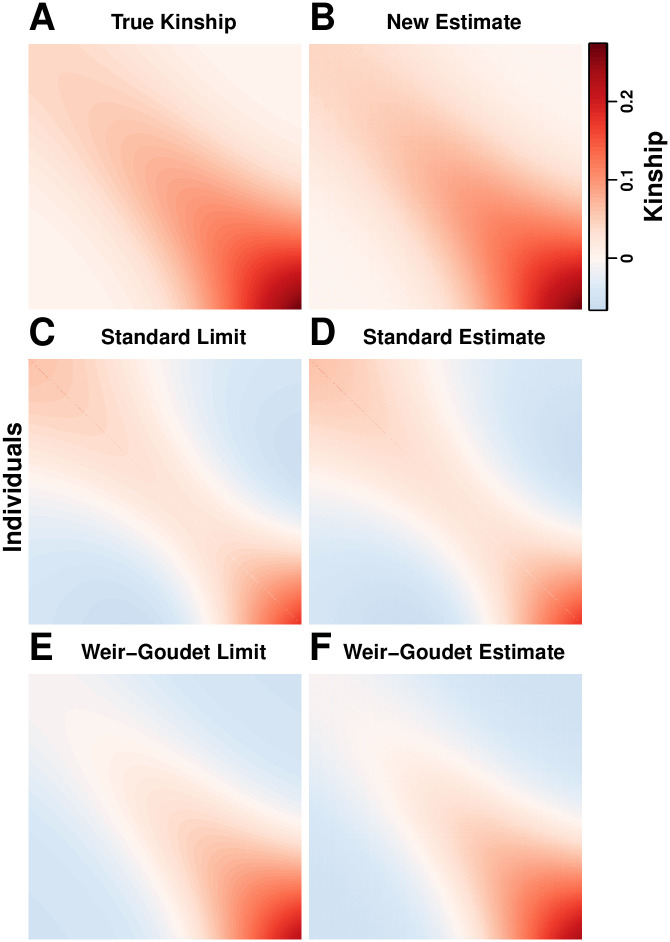

Evaluation of kinship estimators

Our admixture simulation illustrates the distortions of the standard kinship estimator

Evaluation of kinship estimators.

Observed accuracy for two existing kinship coefficient estimators is illustrated in our admixture simulation and contrasted to the nearly unbiased estimates of our new estimator. Plots show n = 1000 individuals along both axes, and color corresponds to

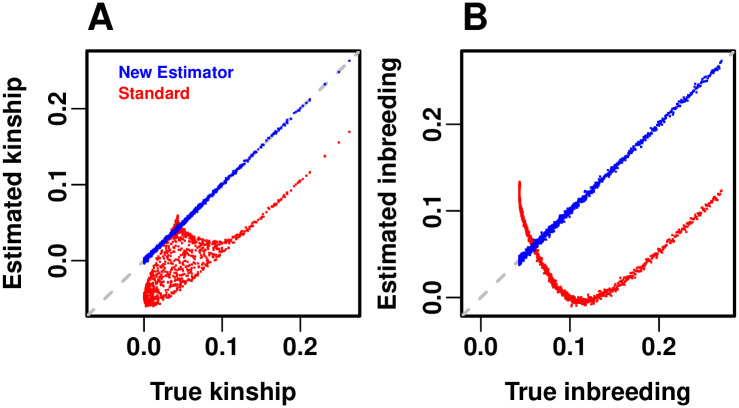

Accuracy of kinship estimators.

Here the estimated kinship values are directly compared to their true values, in the same admixture simulation data (n = 1000 individuals) shown in the previous figure. (A) Kinship between different individuals (excluding inbreeding). The new estimator has practically no bias in this evaluation (falls on the 1-1 dashed gray line). The standard estimator has a complex, non-linear bias that covers a large area of errors. (B) Inbreeding comparison, shows the bias of the standard estimate follows a different pattern for inbreeding compared to kinship between individuals. To better visualize and compare data across panels, a random subset of n points (out of the original n(n − 1)/2 unique individual pairs) were plotted in (A), matching the number of individuals (number of points in (B)).

Our new kinship estimator (Fig 5B) recovers the true kinship matrix of this complex population structure (Fig 5A), with an RMSE of 2.83% relative to the mean

Now we compare the convergence of the ratio-of-means and mean-of-ratios versions of the standard kinship estimator to their biased limit we calculated in Eq (19) (Fig 5D). The ratio-of-means estimate

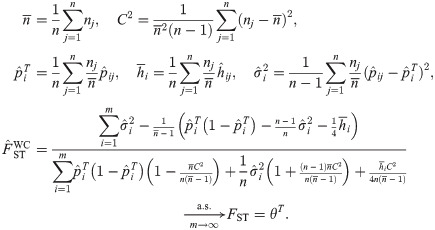

Evaluation of oracle-adjusted FST estimators

Here we verify additional calculations for the bias of the standard kinship-based estimator

Evaluation of standard and adjusted FST estimators.

The convergence values we calculated for the standard kinship plug-in and adjusted FST estimators are validated using our admixture simulation. All adjusted estimators are unbiased but are “oracle” methods, since the mean kinship (

Prediction intervals were computed from estimates over 39 independently-simulated IAF and genotype matrices (Methods, section Prediction intervals). Estimator limits are always contained in these intervals because the number of independent loci (m = 300, 000) is sufficiently large. Estimates that use genotypes have wider intervals than estimates from IAFs; however, IAFs are not known in practice, and use of estimated IAFs might increase noise. Genetic linkage, not present in our simulation, will also increase noise in real data.

Discussion

We studied analytically the most commonly-used estimators of FST and kinship, which can be derived using the method of moments. We determined the estimation limits of convergence of these approaches under two models of arbitrary population structure (Fig 1). We found that no existing approaches estimate the generalized FST (an IBD probability) accurately (but note that some of these approaches intended to estimate a linearly-transformed FST quantity and not the IBD probability). We also showed that the standard kinship estimator is biased on structured populations (particularly when the average kinship is comparable to the kinship coefficients of interest), and this bias varies for each pair of individuals. These results led us to a new kinship estimator, which is consistent if the minimum kinship is estimated consistently (Fig 1). We presented an implementation of this approach, which is practically unbiased in our simulations. Our kinship and FST estimates in human data are consistent with the African Origins model while suggesting that human differentiation is considerably greater than previously estimated [59].

Estimation of FST in the correct scale is crucial for its interpretation as an IBD probability, for obtaining comparable estimates in different datasets and across species, as well as for DNA forensics [3, 7, 19, 20, 78–80]. Our framework results in a new unbiased genome-wide FST estimator. However, our findings may not have direct implications for single-locus FST estimate approaches where only the relative ranking matters, such as for the identification of loci under selection [8, 10, 81–86], assuming that the bias of the genome-wide estimator carries over uniformly to all single-locus estimates. Our convergence calculations in section Assessing the accuracy of genome-wide ratio estimators require large numbers of loci, so they do not apply to single-locus estimates. Moreover, various methods for single-locus FST estimation for multiple alleles suffer from a strong dependence to the maximum allele frequency and heterozygosity [83–85, 87–90] that suggests that a more complicated bias is present in these single-locus FST estimators.

We have shown that the misapplication of existing FST estimators for independent subpopulations may lead to downwardly-biased estimates that can approach zero even when the true generalized FST is large. Weir-Cockerham [17], Weir-Hill [4], HudsonK (which generalizes the Hudson pairwise FST estimator [23] to K independent populations; also equals the Weir-Goudet approach for subpopulations [21]; S1 Text), and BayeScan [10]FST estimates in our admixture simulation are all smaller than the FST target by nearly a factor of two (Fig 4B), and differ from our new FST estimates in humans by nearly a factor of three [59]. To be accurate, existing FST estimators require independent subpopulations, so the observed biases arise from their misapplication to subpopulations that are neither independent not homogeneous. Nevertheless, natural populations—particularly humans—often do not adhere to the independent subpopulations model [59, 91–95].

The standard kinship coefficient estimator we investigated is often used to control for population structure in GWAS and to estimate genome-wide heritability [16, 27, 30–35]. While this estimator was known to be biased [16, 35], no closed-form limit had been calculated until very recently [21, 62]. These kinship estimates are biased downwards on average, but bias also varies for each pair of individuals (Figs 1 and 5). Thus, the use of these distorted kinship estimates may be problematic in GWAS or for estimating heritability, but the extent of the problem remains to be determined.

We developed a theoretical framework for assessing genome-wide ratio estimators of FST and kinship. We proved that common ratio-of-means estimators converge almost surely to the ratio of expectations for infinite independent loci (S1 Text). Our result justifies approximating the expectation of a ratio-of-means estimator with the ratio of expectations [4, 17, 23]. However, mean-of-ratios estimators may not converge to the ratio of expectations for infinite loci. Mean-of-ratios estimators are potentially asymptotically unbiased for infinite individuals, but it is unclear which estimators have this behavior. We found that the ratio-of-means kinship estimator had much smaller errors from the ratio of expectations than the more common mean-of-ratios estimator, whose convergence value is unknown. Therefore, we recommend ratio-of-means estimators, whose asymptotic behavior is well understood.

Our new framework enables accurate FST estimation in more complex datasets than before, but challenges remain. One challenge is the estimation of local inbreeding coefficients, which are required for estimating the generalized FST when not all individuals are locally outbred. To this end, we suggest employing existing approaches that infer inbreeding from large runs of homozygosity or related strategies [66–68], particularly when such self-IBD blocks are much larger than observed between individuals in the same subpopulation. A streamlined approach for jointly estimating total and local inbreeding is desirable, but will require an appropriate evaluation featuring realistic simulation of local inbreeding in a complex population structure. Another challenge is the estimation of the minimum kinship value without the use of subpopulation labels, so that accurate FST estimates can be obtained with even less user supervision. A more general unsupervised method could better ensure accuracy under extreme cases, such as when there are few unrelated individual pairs. These challenges can be overcome with the estimators we have presented, although supervision is needed to ensure that local inbreeding and the minimum kinship are estimated correctly.

We have demonstrated the need for new models and methods to study complex population structures, and have proposed a new approach for kinship and FST estimation that provides nearly unbiased estimates in this setting. Extending our implementation to deliver consistent accuracy in arbitrary population structures will require further innovation, and the results provided here may be useful in leading to more robust estimators in the future.

Methods

Previous FST estimators for the independent subpopulations model

Here we summarize the previous Weir-Cockerham, Weir-Hill, and Hudson FST estimators for independent subpopulations and derive the generalized HudsonK estimator for more than two subpopulations (which also equals the recent Weir-Goudet FST estimator for subpopulations under biallelic loci; S1 Text). We show that each of these estimators reduces, under infinite subpopulation sizes, to

The Weir-Cockerham FST estimator

The Weir-Cockerham (WC) FST estimator [17] estimates the coancestry parameter θT shared by each of the n independent subpopulation in consideration. Let

Now we simplify this estimator as the sample size of every subpopulation becomes infinite. First set the sample size of every subpopulation nj equal to their mean

The Weir-Hill FST estimator

Weir and Hill developed new estimators for subpopulation-specific FST values and considered the effects of non-independent subpopulations [4]. However, these estimators target linearly-transformed FST values, and recover the FST defined in Eq (9) only when subpopulations are independent [4], so we group them here with other estimators that strictly assume independent subpopulations. For simplicity, here we only consider the global FST estimator; the estimators of the coancestry matrix of the subpopulations was found to have the same overall linear transformation [4]. In the limit of infinite subpopulation sizes, this estimator also converges to the asymptotic FST estimator for independent subpopulations (

The Weir-Hill (WH) FST estimator, simplified here for biallelic loci but extended to average over loci, and its limit, are given by

The Hudson FST estimator

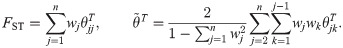

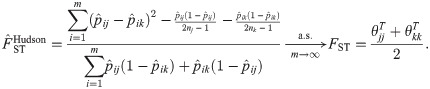

The Hudson pairwise FST estimator [23] measures the differentiation of two subpopulations (j, k). The estimator and its limit for two independent subpopulations (

Generalized HudsonK FST estimator

Here we derive the “HudsonK” estimator (first made available in [58]), which generalizes the Hudson pairwise FST estimator in Eq (40) to n independent subpopulations. This estimator also equals the recent Weir-Goudet FST estimator for subpopulations [21] (for biallelic loci; S1 Text). Note that for independent subpopulations, the FST of all the subpopulations equals the mean pairwise FST of every pair of subpopulations:

Like WC and Weir-Hill,

Simulations

Construction of subpopulation allele frequencies

We simulate K = 10 subpopulations Su and m = 300, 000 independent loci. Every locus i draws

Random subpopulation sizes

We randomly generate sample sizes r = (ru) for K subpopulations and

Admixture proportions from 1D geography

We construct qju from random-walk migrations along a one-dimensional geography. Let xu be the coordinate of intermediate subpopulation u and yj the coordinate of a modern individual j. We assume qju is proportional to f(|xu − yj|), or

Choosing σ and τ

Here we find values for σ (controls qjk) and τ (scales

Prediction intervals

Prediction intervals with α = 95% correspond to the range of n = 39 independent FST estimates. In the general case, n independent statistics are given in order X(1) < … < X(n). Then I = [X(j), X(n+1−j)] is a prediction interval with confidence

BayeScan and Weir-Goudet implementations

Weir-Goudet (WG) kinship estimates [20–22] were calculated using the function snpgdsIndivBeta in the R package SNPRelate 1.20.1 available on Bioconductor and GitHub. We found identical estimates using the function beta.dosage in the R package hierfstat 0.4.30 available on GitHub. WG (individuals) FST estimates were computed from the kinship estimates as described in section Comparison to the Weir-Goudet kinship estimator for individuals.

BayeScan 2.1 was downloaded from http://cmpg.unibe.ch/software/BayeScan/. To estimate FST, first the per-subpopulation FST values were estimated across loci assuming no selection, then the global FST was given by the mean FST across subpopulations.

Software

An R package called popkin, which implements the kinship and FST estimation methods proposed here, is available on the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN) at https://cran.r-project.org/package=popkin and on GitHub at https://github.com/StoreyLab/popkin.

An R package called bnpsd, which implements the BN-PSD admixture simulation, is available on CRAN at https://cran.r-project.org/package=bnpsd and on GitHub at https://github.com/StoreyLab/bnpsd.

An R package called popkinsuppl, which implements memory-efficient algorithms for the Weir-Cockerham, Weir-Hill, and HudsonK FST estimators, and the standard kinship estimator, is available on GitHub at https://github.com/OchoaLab/popkinsuppl.

Public code reproducing these analyses are available at https://github.com/StoreyLab/human-differentiation-manuscript.

References

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

78

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

Estimating FST and kinship for arbitrary population structures

Estimating FST and kinship for arbitrary population structures