Author contributions: J.L.T. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

Self-help books, TED talks, and inspirational memes all claim that finding, following, and fueling one’s passion is critical to success. People should feel passionate about what they do, whom they love, and how they live (1). Consistent with these claims, Li et al. (2) show, in nationally representative samples of 1.2+ million high school students across 59 different cultures, the more “passion” one has for reading, math, and science, the higher one’s achievement scores. However, passion—defined as feelings of enjoyment, interest, and self-efficacy—mattered more in individualistic than in collectivistic cultures. Specifically, one unit of passion translated into an average of 22.67 points on standardized achievement tests in individualistic societies like the United States, Australia, and the United Kingdom, versus an average of only 12.69 points in countries like Columbia, Thailand, and China. If passion is so critical to success, why does it matter more in some cultures than others? And, if passion doesn’t matter as much in more collectivistic cultures, what does?

Based on decades of research, the authors (2) suggest that the answer may lie in the different models of self that individualistic vs. collectivistic cultures foster (3, 4). In individualistic cultures, people are encouraged to be more “independent,” or to see themselves as separate from others, whereas, in collectivistic cultures, people are encouraged to be more “interdependent,” or to see themselves as connected to others. These models are reflected in and reinforced by products, practices, and institutions that are widely distributed in these cultures (3, 4). Consequently, people in individualistic cultures have more “independent” goals, which include expressing their preferences and molding their surroundings to those preferences. In contrast, people in collectivistic societies have more “interdependent” goals, which include attending and adjusting to their surroundings (5). But what do these goals have to do with passion?

Achieving these goals requires varying levels of arousal and action. Our research finds that, because achieving independence requires increased arousal and action, cultures that foster these goals value high-arousal positive states like passion, excitement, and enthusiasm. In contrast, because achieving interdependence requires decreased arousal and action, cultures that foster these goals value low-arousal positive states like calm, peacefulness, and balance (6). As a result, although people can experience similar feelings around the world, people value and ideally want to feel different feelings, depending on whether their cultures promote independence or interdependence. For instance, in the United States and Canada, people value excitement, enthusiasm, and other high-arousal positive states more, while people in different parts of East Asia (e.g., Hong Kong, Taiwan, South Korea, Japan) value calm, peacefulness, and other low-arousal positive states more (78–9, but also see 10). These affective ideals are pervasive throughout these cultures, popping up everywhere from children’s storybooks, to magazine ads, to politicians’ press photos, to other forms of popular media (8, 11, 12).

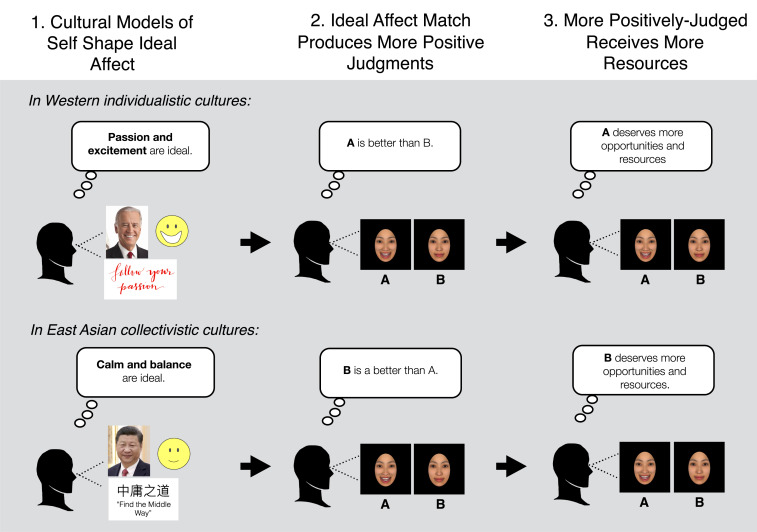

These ideals matter because people use them to judge their own feelings (13), and, perhaps even more importantly, to judge the feelings of others. For instance, because European Americans value excitement more than Hong Kong Chinese, they rate “excited” faces (with broad toothy smiles) as much friendlier and warmer than “calm” faces (with closed smiles), compared to Hong Kong Chinese (14). And, because European Americans perceive excited (vs. calm) faces as friendlier and warmer, they share more money with excited vs. calm partners in economic games (e.g., the Dictator Game), compared to East Asians (15). In other words, as shown in Fig. 1, when people see faces that match their ideal affect, they judge them more positively, and, because of these positive judgments, they share more resources with them.

How matching cultural affective ideals may increase opportunities and resources. Joe Biden image credit: Wikimedia Commons/Andrew Cutraro. Xi Jinping image credit: Wikimedia Commons/US Department of State. Computerized faces were generated using FaceGen Modeller (version 3.5).

Experiencing and expressing cultural ideals can have life-altering consequences in the real world. When deciding whom to lend to on a web-based microlending platform (Kiva.com), people from countries with an excitement ideal loaned more to borrowers who had “excited” smiles in their profile photos and less to borrowers who had “calm” smiles (16). In a business setting, when selecting an intern, European Americans viewed the “ideal applicant” as being more excited (vs. calm), and chose more excited (vs. calm) applicants than Hong Kong Chinese did (10, 14). Even in health settings, European Americans chose excitement-focused physicians who promoted dynamic lifestyles (vs. calm-focused physicians who promoted relaxing lifestyles) more than Hong Kong Chinese did. Interestingly, European Americans also recalled and adhered to the recommendations of the excitement- versus calm-focused physician more than East Asian Americans did (17). These findings suggest that people may also be more receptive to the advice and feedback of people who express their cultural ideal.

Together, these findings may provide one explanation for why passion matters more for academic achievement in individualistic cultures. When students experience and express passion, excitement, and other high-arousal positive states in individualistic cultures, they match the cultural ideal. As a result, they get a cultural boost: Their teachers and parents evaluate them more positively and bestow more resources and opportunities on them, which may ultimately lead to achievement gains. When students express passion in collectivistic cultures, however, they do not receive the same boost. Why? Because, instead of passion and excitement, these collectivistic cultures value calm, balance, and other low-arousal positive states that help people achieve interdependence. Therefore, in these contexts, students should get a cultural boost when they experience and express calm and balance. Indeed, Li et al. (2) find that, in more collectivistic societies, parental emotional support—an index of interdependence—mattered more for academic achievement.

The findings of Li et al. (2) add to a growing literature that highlights how cultural affective ideals implicitly but widely shape important life outcomes. For instance, while negative affective experience has been associated with worse physical and psychological health in both the United States and Japan, this association was much weaker for Japanese—perhaps because Japanese culture values negativity more than US culture does (18). Even within cultures, differences in affective ideals can make a difference: In a German sample, the more people valued negative affect, the weaker the association between their experiences of negative affect and poor health (19). These affective ideals likely influence other outcomes as well—satisfaction with intimate relationships, job longevity, and even adaptation to aging.

More research is needed—especially work that examines whether these processes generalize to other individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Furthermore, as Li et al. (2) argue, researchers must measure both independent and interdependent ideals in their studies of achievement, health, and other life outcomes. Once identified, these ideals could be used to cultivate academic achievement and other desirable outcomes across and within different cultures. More research is also needed to examine how cultural differences in ideal affect may inadvertently reinforce group stereotypes in multicultural societies like the United States and what we can do to dispel them. For instance, in the context of a European American focus on passion, calm East Asian Americans are often inaccurately judged to be “cold” and “stoic” (20). This may explain why, compared to European Americans, East Asian Americans are less likely to be promoted to top leadership positions, a problem often described as “the Bamboo Ceiling” (21). But this might be avoided if teachers, employers, and other decision makers in individualistic cultures understood that in many cultures—as illustrated by the findings of Li et al. (2)—passion matters less. Instead of passion, people are finding, following, and fueling calm, balance, and the other affective states that their cultures value more.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

Why does passion matter more in individualistic cultures?

Why does passion matter more in individualistic cultures?