Author contributions: C.E.B.-H. analyzed data and wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

Competition for resources is a decisive driver for success. Entire civilizations have collapsed when food scarcity leads to conflict. Competition for nutrients has also shaped evolution, with modern-day species descending from the victors. While archeological digs and historical accounts yield insight into how resource competition impacted human history, whole-genome sequencing is needed to understand the inherited adaptations that passed the filter of natural selection. Leveraging comparative genomics, García-Cañas et al. (1) report their discovery of how cyanobacteria won the arms race when confronted with resource limitation caused by copper deficiency. Cyanobacteria are an ancient group of bacteria credited with the evolution of oxygen-producing photosynthesis, a process with an absolute requirement for metal cofactors, including iron, manganese, and copper. García-Cañas et al. (1) find that a BlaI-family transcription factor and BlaR1-family protease evolved to regulate the transcription-mediated swap of copper-dependent plastocyanin (PC) for iron-dependent cytochrome c6 (Cytc6) (1). Over 40 y ago, researchers studying green algae (2) and cyanobacteria (3) proposed that replacement of PC with Cytc6 provides a strategy to maintain photosynthesis with a “back-up” protein when PC becomes inactivated due to copper insufficiency, but how this interchange is regulated in cyanobacteria remained unknown until now.

PC and Cytc6 are functionally identical, small, soluble, electron-transfer proteins that transfer one electron at a time from the cytochrome b6f complex to photosystem I during oxygenic photosynthesis. However, that is where their similarities end. The two proteins are evolutionarily unrelated, differing in both primary sequence and tertiary structure. The most striking difference between these two isofunctional proteins is their cofactors. Cytc6 contains a tetrapyrrole-bound iron atom (i.e., heme) that switches between Fe3+ and Fe2+ to accept and donate an electron. Conversely, PC utilizes a single copper ion that switches between Cu2+ and Cu1+ to accept and donate an electron. Although aqueous iron and copper ions have dramatically different redox potentials (the standard reduction potential of Fe3+ is 0.77 V and of Cu2+ is 0.159 V), the metal ions in PC and Cytc6 are tuned to roughly 370 mV, the redox potential needed to catalyze the transfer of an electron from cytochrome f to P700+ in photosystem I (in cyanobacteria and green algae) or to the respiratory terminal oxidase (in cyanobacteria).

In addition to showcasing the role of polypeptides in manipulating the chemical properties of metal cofactors, these two proteins are a remarkable example of convergent evolution driven by access to metals. Based on historical estimates of iron and copper bioavailability, Cytc6 is thought to have evolved first. Before oxygen levels in the atmosphere rose due to oxygenic photosynthesis in the early Paleoproterozoic [∼2,400 Ma (4)], iron was plentiful (the fourth-most-abundant element in Earth’s crust) and bioavailable as the water-soluble, reduced form of iron (Fe2+). However, as oxygen levels increased, iron became more limited, as oxidation of Fe2+ resulted in the insoluble form of iron (Fe3+). At the same time, copper that was previously locked in the water-insoluble Cu1+ state was oxidized to the more soluble Cu2+ state, leading to the evolution of copper-dependent proteins, such as PC.

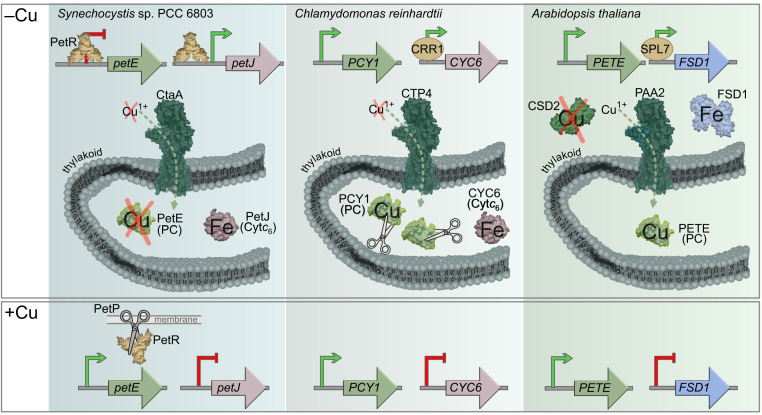

The availability of two isofunctional proteins, one that uses a copper ion and one that uses a heme cofactor, facilitated nutritional flexibility. Some oxygenic phototrophs, such as land plants and a handful of green algae, only contain PC, while others, such as red algae, only contain Cytc6. A third group, composed of green algae and cyanobacteria, contains genes for PC and Cytc6. The presence of both genes enables these phototrophs to “pick” which protein, and, therefore, which metal cofactor, to use for electron transfer. PC is expressed if copper is plentiful; when copper becomes limiting, PC is replaced with Cytc6. As characterized previously in the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, a plant-specific transcription factor, CRR1, activates transcription of the Cytc6-encoding gene during copper deficiency (5), expression of the PC-encoding gene is constitutive (6), and an unidentified protease(s) targets both copper-bound PC and metal-free PC for degradation (7, 8) (Fig. 1). Although the outcome is the same, and green algae likely acquired the genes for PC and Cytc6 through gene transfer from the cyanobacterium-like progenitor of the chloroplast, García-Cañas et al. find that the regulatory mechanism responsible for the PC/Cytc6 exchange is not conserved between cyanobacteria and green algae (1).

Comparison of PC/Cytc6 regulation across oxygenic phototrophs. In cyanobacteria, green algae, and land plants, the functional orthologs CtaA, CTP4, and PAA2, respectively, pump Cu1+ into the thylakoid lumen for PC biogenesis (1415–16). In cyanobacteria and green algae, where genes encoding both PC and Cytc6 are present, copper depletion leads to replacement of PC with Cytc6. As described by García-Cañas et al. (1), in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 transcription is regulated by binding of PetR to the promoters of petE and petJ. In turn, PetR is regulated posttranslationally by the protease PetP in the presence of copper. By comparison, in C. reinhardtii transcription of PCY1, encoding PC, is constitutive, while transcription of CYC6, encoding Cytc6, is activated by CRR1. PC abundance is regulated posttranslationally by an unidentified protease. In land plants, copper distribution to PC is prioritized during copper deficiency in part by the copper-regulated replacement of stroma-localized Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (CSD2) and Fe-dependent superoxide dismutase (FSD1) (17). The CRR1 functional ortholog SPL7 activates transcription of FSD1 and an artificial microRNA family (miR398) that simultaneously reduces transcript abundance of CSD2 (18).

Since PC- and Cytc6-encoding genes (petE and petJ, respectively) are regulated by copper at the transcriptional level (9, 10) in cyanobacteria, García-Cañas et al. (1) performed a comparative genomic analysis of available cyanobacterial genomes with a focus on identifying putative transcription factor genes neighboring petE or petJ. They identified an orthologous group of genes encoding an uncharacterized BlaI-like transcription factor (named PetR) and a neighboring orthologous group of genes encoding an uncharacterized BlaR1-like protease (named PetP). To test the hypothesis that these proteins are responsible for the reciprocal expression of petE and petJ, García-Cañas et al. (1) leverage Synechocystic sp. PCC 6083 as a reference experimental system. Interpretation of petE and petJ transcript abundance in petR and petP deletion strains combined with evidence from electrophoretic mobility shift assays leads to the conclusion that PetR is needed to repress the expression of petE and activate the expression of petJ (Fig. 1). PetP has an opposite effect on expression consistent with the role of this protease in PetR degradation. In the consequential absence of PetR, petE expression is no longer repressed and petJ expression is no longer induced, phenocopying the petR mutant. García-Cañas et al. (1) further propose that PetP has copper-dependent protease activity, providing a mechanism for copper sensing. Coincidently, an unidentified copper-activated protease has also been found to play in role in copper-sensing by Enterococcus hirae (11), suggesting that the role of proteases in regulating copper-responsive transcription extends beyond cyanobacteria.

In addition to uncovering a paradigm in copper sensing, the findings of García-Cañas et al. (1) provide the foundation for exciting research avenues. Although dual activator–repressor activity has been described for other transcription factors that regulate metal homeostasis, such as Zur (12), the mechanism enabling opposite outcomes of transcription factor–DNA binding by PetR is unknown. Future work into the copper-regulated activity of PetP promises to reveal a new mechanism for establishing fidelity of metal selectivity in regulatory circuits. Additionally, RNA sequencing of petP and petR mutant strains reveal that the copper-regulated PetRP regulon only encodes four proteins: PC, Cytc6, and two proteins of unknown function (1). Of these two uncharacterized proteins, Slr0602 was previously found to interact with six photosynthetic proteins, including PC (13), suggesting that replacement of PC with Cytc6 may involve posttranslational adjustment of some photosynthetic complexes, hinting at potentially uncharted complexity.

Acknowledgements

I acknowledge support from the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, as part of the Quantitative Plant Science Initiative at Brookhaven National Laboratory

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Cyanobacteria provide a new paradigm in the regulation of cofactor dependence

Cyanobacteria provide a new paradigm in the regulation of cofactor dependence