Forces and Main Results

We begin with a streamlined setting, in which an equilibrium interest rate and distribution of wealth depend on preferences and opportunities in a continuous-time economy populated by a unit measure of ex ante identical, but ex post heterogeneous, agents who have random life spans. After isolating forces that generate wealth inequality, we investigate how adding sources of ex ante heterogeneity alters equilibrium wealth distributions. Our model makes cross-sectional wealth more unequal and fatter-tailed than labor earnings, as is true in US data.

Choices.

A person is born at age 0 and dies at a random nonnegative age that is exponentially distributed with a constant death rate λ per unit of time, as in ref. . An agent ranks consumption processes {Ct}t=0∞ by

where

ρ>0 is a discount rate,

E [⋅] is a mathematical expectation with respect to the probability distribution of

τ, and

Each person inelastically supplies

H>0 hours of labor. People of the same age are equally productive. Labor earnings at age

t equal

Yt=Y0 egt for

0≤t<τ, where

g>0. Earnings growth reflects increased labor efficiency from experience. Let

X denote an agent’s wealth process. All agents start life with

X0=0 and identical labor earnings

Y0. This is the sense in which they are ex ante identical.

As in refs. and , we assume that people can purchase an actuarially fair “reverse-life-insurance” contract that provides payments at rate of λXt until death in exchange for agreeing to transfer end-of-life wealth Xτ− to an insurance company.

A random variable St=0 if an agent is alive, and St=1 otherwise. For (0≤t<τ), wealth evolves as

The term in brackets is the saving rate

X˙t. The rate of return on savings equals the sum of the actuarially fair payment rate

λ and the risk-free rate

r. The term that multiplies

dSt is a transfer of the agent’s wealth

Xτ− just prior to death to the insurance company at death moment

τ, i.e., when

dSt=1.

A person can dissave when savings Xt are positive, but cannot borrow against future labor earnings, i.e.,

Each person maximizes utility functional subject to the law of motion [] and an associated transversality condition.

We complete our model as did ref. by letting a representative firm operate a Cobb–Douglas production technology. A representative firm operates a production function F(K,L)=AKαL1−α, where A>0, α∈(0,1), K is the aggregate capital stock, and L is aggregate labor demand. Physical capital depreciates at a constant rate δ>0. The firm rents capital and labor in competitive markets. The firm’s optimization problem implies that a competitive equilibrium interest rate r and wage index w satisfy:

Equilibrium.

Across people, random deaths are statistically independent. To sustain a constant population, we replenish the economy with new people born at a constant rate λ per unit of time. By a law of large numbers, the insurance company always breaks even by using its receipts to cover its payments to living annuity owners. In equilibrium, capital demand equals capital supply:

where

ϕX(X) is the cross-section stationary probability density of wealth

X.

In equilibrium, labor demand equals labor supply: L=H. The wage index w equals an average wage rate across all agents so that w=E(Y)/H. Because aggregate labor cost wL equals aggregate labor earnings, a law of large numbers implies

where

ϕY(Y) is the cross-section stationary distribution of labor earnings. Therefore, an agent’s labor earnings

Yt exceeds the average level

E(Y) if and only if her wage rate

Yt/H at

t exceeds

w.

, , and imply that the equilibrium interest rate r and wage rate w received by an agent with average labor efficiency satisfy

We calculate a cross-section marginal stationary distribution of wealth by integrating a cross-section joint distribution of wealth and earnings. Where

C(X,Y) is a decision rule for consumption and

μX(X,Y)=(r+λ)X+Y−C(X,Y), the following Kolmogorov Forward (Fokker–Planck) equation describes the cross-section joint distribution

ϕXY(X,Y):

A stationary recursive competitive equilibrium consists of value functions, decision rules for consumption, an interest rate

r, an average wage rate

w, stationary population demographics, and a stationary distribution for a cross-section joint distribution for wealth and earnings

(X,Y) such that

1)Given r and the labor-earnings process {Ys:s≥0} and X0, decision rules solve each person’s lifetime savings problem;

2)The interest rate r and wage index w satisfy [] and [];

3) and hold so that markets for capital and labor clear;

4)The cross-section distribution of wealth and earnings ϕXY(X,Y) is time-invariant and satisfies .

Computing Equilibria

We provide analytic formulas to isolate forces that determine equilibrium outcomes..

To assure existence of equilibrium objects, we assume

so that the death rate

λ exceeds the earnings growth rate

g that exceeds zero. To compute a stationary equilibrium, we proceed as follows. We start from an exogenous cross-section distribution of labor earnings governed by a power law. Next, for a given interest rate that is consistent with positive aggregate savings, we use an optimal decision rule for consumption together with budget constraints to deduce dynamics of each person’s wealth and an implied cross-section distribution of wealth. Then, we compute an interest rate that equates aggregate supplies of labor and capital to aggregate quantities that firms demand.

Cross-Section Earnings Distribution.

Labor earnings grow according to Yt=Y0 egt, and length of life is the only source of heterogeneity across people. Along with Condition [], a constant mortality rate λ implies that the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the cross-section of earnings is

where

with mean

Evidently,

ΦY(Y) has a fat tail with a power-law exponent

ξY=λ/g>1. Researchers including refs.

10111213–

14 also combined exponential growth with a constant exit rate to attain such results.

implies the following Lorenz curve of labor earnings:

The fraction of labor earnings earned by the top

(10×u) percent of people that goes to the top

u percent is constant:

Condition [] (

λ>g) implies

FIY(u)>0.1, which means that earnings have a fat right tail with a constant

FI for all admissible levels of

u.

By using , we obtain the following formula for the Gini coefficient of labor earnings:

Inequalities [] imply

0≤ΓY<1/2. The higher the earnings growth

g, the larger the earnings inequality. For the special case with no growth (

g=0),

ΓY=0.

Optimal Consumption.

A scalar

converts a unit of labor-earnings

Yt into human wealth

qYt in the sense of ref. . Thus,

becomes the sum of financial and human wealth. Total wealth

{Pt;t≥0} serves as s single state variable that determines a person’s lifetime utility when

Xt>0 at all

t>0 before death. Because the market structure allows people to hedge mortality risk, the optimal consumption rule is linear in total wealth

Pt:

where

m is the marginal propensity to consume (MPC):

Consumption

Ct and total wealth

Pt both grow exponentially at a rate

r−ργ that equals the product of wedge

(r−ρ) and the elasticity of intertemporal substitution

1/γ:

Therefore,

Pt=Xt+qYt=P0 e(r−ρ)t/γ and

Ct=mP0 e(r−ρ)t/γ. Below, we call decision rule [] a

Ramsey rule.

Wealth as a Function of Earnings.

A person’s age t is tied to her earnings by t=lnYt/Y0g, and wealth Xt at age t satisfies

Because

Xt is positive at all

t, we know that

X(Y) is increasing in

Y. For

X(Y)>0 and

X′(Y)>0 on

(0,+∞), it is necessary that

r−ργ>g, i.e.,

So an equilibrium interest rate

r has to exceed

ρ, an agent’s discount rate. That condition is violated by the

r<ρ equilibrium outcome in refs. , , and models with infinitely lived agents. Indeed, [] asserts something even stronger, namely, that the interest rate

r must exceed

rramsey, the

augmented golden rule interest rate for a Ramsey nonstochastic optimal growth model.

Inequality [] also implies that the growth rate of consumption exceeds the growth rate of earnings, a consequence of a constant MPC out of total wealth and the existence of stationary equilibrium. Since inequality [] holds, Eq. implies that wealth is a convex function of earnings. That shape amplifies wealth inequality relative to earnings inequality.

Cross-section wealth is less equally distributed and has a fatter tail than nonfinancial earnings because individuals’ optimal saving choices make their financial wealth always grow at a faster rate than nonfinancial earnings. Younger people own less financial wealth, so they choose to make their wealth grow at faster rates than do older people. Growth rates of wealth still exceed growth rates of nonfinancial earnings for very old people. The higher growth rate of total wealth than of nonfinancial earnings combines with compound interest to widen the wealth distribution and fatten its right tail relative to earnings.

Cross-Section Wealth Distribution.

The inverse function X(Y) presented in is increasing in Y under Condition []. In a stationary equilibrium, those who live longer have higher earnings and more wealth. Indeed, the CDF of wealth, which we denote by ΦX(X), satisfies ΦX(Xt)=ΦY(Yt), which implies

Therefore, the mean of cross-section wealth,

X, is

The cross-section distribution of wealth

X is asymptotically fat-tailed with a power-law exponent

This follows from

where the first equality uses [], the second equality uses [] and inequality [], and the third equality follows from []. Researchers, including refs.

910–, , and , have obtained similar results.

Unlike the cross-section earnings distribution that satisfies a power law over the entire support of Y, the cross-section wealth distribution satisfies a power law only in the limit as X→∞. Thus, the fraction of wealth owned by the top 10×u percent that goes to the top u percent of people, which we denote by FIX(u), obeys

where

ξX is given in . .

From Micro to Macro.

Inequality [] and together imply that ξX<λ/g: Cross-section wealth has a fatter right tail than earnings since the power-law exponent ξX of cross-section wealth is smaller than the exponent λ/g of cross-section earnings.

In Appendix, we derive the following formula for the Lorenz curve of wealth:

and the following formula for the Gini coefficient of wealth:

Our Condition [] asserts that

λ>g implies that the Gini coefficient for wealth is larger than for earnings:

ΓX>ΓY.

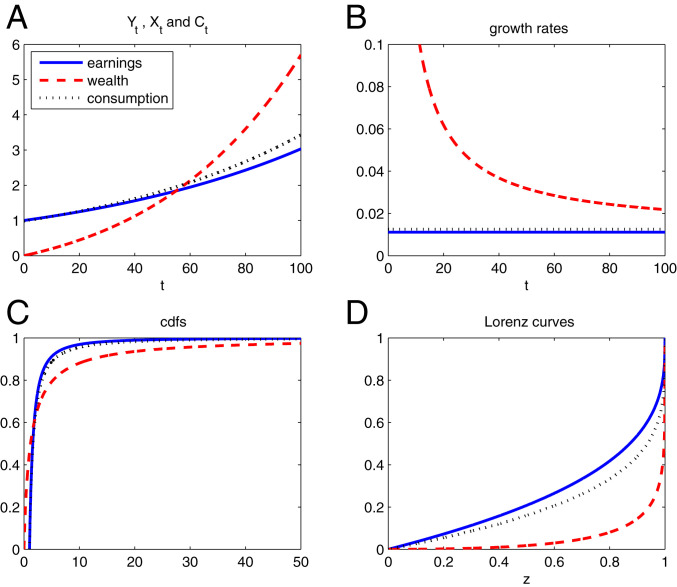

Fig. 1 illustrates the mechanism that generates a fatter-tailed distribution for cross-section wealth than for earnings. Fig. 1 A and B show that earnings Y grow at a constant rate g that is lower than the consumption growth rate (r−ρ)/γ. This occurs because X grows at a nonlinear rate greater than consumption and earnings growth rates. While the growth rate of wealth Xt˙/Xt decreases with age after starting from ∞ at X0=0, Xt˙ increases with age.

Fig. 1.

Earnings, wealth, and consumption: micro dynamics and macro cross-section distribution. A plots the levels of Yt, Xt, and Ct. B plots the corresponding growth rate of change over time: X˙t/Xt, Y˙t/Yt, and Ċt/Ct. C plots the CDFs of Y, X, and C. D plots the equilibrium stationary cross-section Lorenz curves for Y, X, and C. Parameter values are γ=2, ρ=5%, α=0.36, δ=6%, A=0.896, λ=0.0167, g=1.1%, and σ=0.

Fig. 1C plots cross-section distributions of Y, X, and C. Fig. 1D plots corresponding Lorenz curves. CDFs for both earnings and consumption are described globally by power laws having different exponents. Because our agents prefer to smooth consumption over time, it may at first appear surprising that the distribution of consumption is fatter-tailed than the distribution of earnings. But Condition [] reveals that, in equilibrium, consumption grows faster than earnings. The distribution of wealth is not globally Pareto as earnings and consumption are, but instead approaches the shape of a Pareto distribution with the same power-law exponent as consumption as X→∞. Fig. 1D shows that wealth has a substantially steeper/convex Lorenz curve than consumption, which, in turn, has a steeper/convex Lorenz curve than earnings Y does. Consequently, the Gini coefficient for X is larger than it is for consumption C, which is larger than it is for labor earnings Y.

Note that the Gini coefficient, Lorenz curve, and tail fatness all provide the same inequality rankings for cross-section consumption, labor earnings, and wealth. Such identical rankings won’t prevail after we add ex ante heterogeneity across agents.

Aggregate Earnings, Wealth, and Interest Rate.

In a stationary equilibrium, dKt=dE(Xt)=0. Summing over the wealth dynamics given in across all agents and using a law of large numbers, we obtain the following relation for aggregate variables:

rE(X) is an annuity payment on aggregate wealth, and

E(Y) is aggregate labor earnings. Note that the life-insurance company’s transfers to the living equal its receipts from the dying and, hence, do not appear in .

We have National Income and Product Accounts typical of models in the ref. 23– tradition:

The first equality follows from Euler’s theorem applied to a Cobb–Douglas aggregate production function; the second equality uses the firm’s first-order conditions for factors of production:

FK(K,L)=(r+δ) and

FL(K,L)=w; the third equality follows from market-clearing conditions

K=E(Xt) and

wL=wH=E(Yt); and the fourth equality follows from [].

To compute a stationary equilibrium interest rate, take the firm’s first-order conditions for capital and labor, r+δ=FK(K,L) and w=FL(K,L), and then substitute [] and [] for E(Y) and E(X), respectively, to obtain

A version of the preceding equation appears also as and in appendix B.1.1 of ref. .

This string of equalities implies a quadratic equation that restricts the stationary equilibrium r:

The equilibrium interest rate is the positive root of . Evidently,

Fig. 2 reveals that the equilibrium interest rate satisfies:

Fig. 2.

The quadratic function Ψ(r) given in . The equilibrium interest rate satisfies Ψ(r*)=0 and (ρ+γg)<r*<(ρ+γλ) when λ>g≥0, as assumed in Condition [].

Quantitative Inputs and Outputs

Parameter Choices.

To isolate sources of new findings about the equilibrium wealth distribution that our model brings, we purposefully choose consensus parameter values from the literature. Thus, we set commonly used values γ=2 and an annual discount rate ρ=5%. We set preference and production function parameters to values used by refs. 18–. Following refs. and , we set the capital share of national income, α, to 0.36. We set an annual depreciation rate of capital, δ, to 6% to match an estimate of the US depreciation-output ratio reported by ref. . We want an aggregate capital-output ratio equal to three, as in refs. and , which, in light of , leads to an equilibrium interest rate r of 6% per annum, as in refs. and . Along with refs. and and others, we interpret the equilibrium risk-free rate in our model as a broad measure of average returns on capital. This is why we calibrate an annual (real) risk-free rate to be approximately 6%. We set the productivity parameter A to 0.9, so that the wage rate w for an agent with the average labor efficiency equals unity (a normalization). We set λ=0.0167 in order to set an agent’s expected lifetime at 1/λ=60 years, as in ref. .

Role of Earnings Growth g.

In Table 1, we conduct a comparative static exercise with respect to the earnings growth rate g. In addition to the equilibrium interest rate r, we report Gini coefficients for earnings and wealth (ΓY and ΓX), power-law exponents (ξY and ξX) for the tail, and fractal inequalities (FIY and FIX) for the tail.

Effects of earnings growth rate g

| g | r, % | ΓY | ΓX | ξY | ξX | FIY | FIX |

| 0 | 5.88 | 0 | 0.58 | ∞ | 3.79 | 0.10 | 0.18 |

| 0.5% | 6.60 | 0.18 | 0.72 | 3.34 | 2.08 | 0.20 | 0.30 |

| 1% | 7.34 | 0.43 | 0.87 | 1.67 | 1.43 | 0.40 | 0.50 |

| 1.29% | 7.77 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 1.29 | 1.21 | 0.59 | 0.68 |

First, consider a case with g=0. There is zero cross-section earnings inequality (hence, ΓY=0, ξY=∞, and FIY=0.1). An equilibrium interest rate r=5.88% that exceeds the annual rate of time preference ρ=5% makes young people want to save. Our analytical formulas indicate that wealth has a power-law exponent of ξX=γλ/(r−ρ)=2×(1/60)/(0.0588−0.05)=3.79, a Gini coefficient of ΓX=1/(2−ξX−1)=0.58, and fractal inequality FIX=10(1/ξX)−1=0.18 for all z. The fraction of wealth earned by the top 0.1% of people that goes to the top 0.01% is 18%, which, because it is larger than 10%, indicates that wealth is fat-tailed.

The g=0 (first) row in Table 1 shows that, in equilibrium, the pure life-cycle savings motive for young people, all of whom are born with no (or small) wealth, can generate a fat-tailed wealth distribution, even when their labor earnings are perfectly equal and wealth inequality is entirely driven by how long different agents live.

At a given interest rate r, a higher labor-earnings growth rate g strengthens incentives to borrow against future income to finance current consumption. To encourage savings and clear the asset market, the equilibrium r must increase with g. Also, as g increases, (aggregate) labor becomes more productive, which raises firms’ demand for capital because capital and labor are complements.

Thus, as g increases from 0 to 1%, cross-section earnings inequality increases because older people have higher earnings: The Gini coefficient for cross-section earnings increases from zero to ΓY=1%/(2×(1/60)−1%)=0.43, and the earnings tail becomes fatter (with the power-law exponent ξY decreasing from ∞ to λ/g=(1/60)/1%=1.67). As a result, the fraction of earnings received by the top 0.01% of agents that goes to the top 0.1% equals 40%: FIY=101/ξY−1=10(1/1.67)−1=40%, a fraction whose excess over 10% indicates substantial earnings inequality among the earnings-rich.

In order to elicit saving, the equilibrium interest rate increases from 5.88% to 7.34%. When g=1%, the return on savings is greater than when g=0 because the equilibrium interest rate is higher. As a result, cross-section wealth inequality increases substantially. The Gini coefficient for wealth ΓX increases to 0.87 from 0.58; the wealth tail becomes fatter with the power-law exponent ξX=γλ/(r−ρ) decreasing to 2×(1/60)/(7.5%−5%)=1.43 from 3.79; and the fraction of wealth owned by the top 0.01% of agents owned by the top 0.1% increases to FIX=10(1/ξX)−1=10(1/1.43)−1=50% from 18%.

Finally, if we adjust parameters to make the Gini coefficient of earnings equal 0.63, the value reported in refs. and , we obtain g=1.29%. In this case, the annual equilibrium interest rate is 7.77%, and the wealth Gini coefficient is 0.95, significantly higher than its value of 0.78 in the US data. What makes cross-section wealth that much fatter-tailed than earnings is that the equilibrium interest rate is high and so many agents live so long, or, if we reinterpret the mortality parameter as partly measuring intergenerational bequest motive, that they care so much about their descendants. Ref. analyzes a setup like this. See their p. 7 discussion on “finite lives and stochastic altruism” and their online appendix B.1.3. Enriching the mortality specification would allow us to improve fits here..

Table 1 confirms two insights about sources of wealth inequality. First, a higher growth rate of earnings increases Gini coefficients and fattens right tails of both earnings and wealth. Second, for all levels of g, wealth inequality is larger than earnings inequality, whether we measure them with Gini coefficients (ΓX>ΓY), power-law exponents for right tails (ξX<ξY), or fractal inequalities (FIX>FIY). This occurs because older people are both earnings-rich and wealth-rich; their voluntary savings makes their wealth grow at a faster rate than their earnings. However, the result that wealth has a fatter tail than earnings may not hold when there is ex ante heterogeneity.

Table 1 confirms that the equilibrium interest rate r exceeds the earnings growth rate g. The mechanism here is related to, but distinct from, one posited by ref. , which sees an r>g condition as the fulcrum that creates wealth inequality. Unlike ref. , our model with its ex post heterogeneous agents explicitly incorporates equilibrium consumption responses of the type analyzed in refs. (23–). Despite the action of the impatience parameter ρ>0 in making them prefer to front-load their consumption profiles, agents accept upward-sloping consumption profiles that fit together with an equilibrium age-dependent wealth growth rate that is larger than (r−ρ)/γ, which, in turn, exceeds the earnings growth rate g. These outcomes prevail because, in equilibrium, an individual’s wealth accumulates at a rate higher than earnings.

Ex Ante Heterogeneity

Ref. documents that ex ante heterogeneity influences equilibrium wealth distributions. Ref. shows how positing different discount rates across agents can help match equilibrium wealth distributions. We can extend our baseline model to allow for this and other varieties of ex ante heterogeneity. Thus, suppose that groups of people, A and B, differ in earnings growth rates (gA and gB) , elasticity of intertemporal substitution (1/γA and 1/γB), subjective discount rates (ρA and ρB), or death (or dynasty exit rates) λA and λB. Let θ denote the population of type-A agents and (1−θ) denote the population of type-B agents. Assume λA>gA≥0 and λB>gB≥0, so that stationary earnings distributions exist for both groups.

Cross-Section Earnings Distribution.

The CDF for cross-section earnings is

and so has a fat tail with a power-law exponent equal to

min{λA/gA,λB/gB}. A higher earnings growth rate

g or a lower death/exit rate

λ makes the tail of the distribution fatter. Using [], we obtain economy-wide average earnings:

Cross-Section Wealth Distribution.

Let

where

N=A,B and

A financially unconstrained type-

N agent optimally chooses a linear Ramsey consumption rule at all

t, and her optimal consumption growth rate equals

(r−ρN)/γN. Fraction

πN is defined as the earnings growth rate

gN divided by this optimal consumption growth rate

(r−ρN)/γN. But if the no-borrowing constraint binds

Xt≥0, that Ramsey rule cannot be used for all

t. Nevertheless, the definition of

πN helps us to characterize the cross-section wealth distribution. We provide conditions under which Ramsey linear consumption rules are optimal for both groups or only for group

B and then characterize associated cross-section wealth distributions.

Ramsey rules for both groups.

Consider the case where

This condition means that for both groups, Ramsey consumption rules are feasible and optimal. So each agent saves and sees its wealth

Xt increasing with age

t. Therefore, the earnings growth rate is lower than the consumption growth rate in equilibrium.

The CDF or cross-section wealth for type N=A,B is

where

YN(X) is the value of

Y that solves

X=XN(Y):

When

πN<1, the power-law exponent for the right tail of wealth distribution (for type-

N agents) equals the product of

πN and

λNgN, which we denote by

ξXN:

As noted in [], since

λN>gN is required to ensure that a stationary earnings distribution exists,

ξXN>πN is satisfied when

πN<1 because

ξXN>1.

The CDF of the cross-section wealth distribution is

so cross-section wealth is asymptotically fat-tailed with power-law exponent

ξXwhere

ξXN is the power-law exponent of the wealth distribution for

N=A,B given in []. The wealth-rich who are at the right tail are long-lived ones from the group and have a lower value of the power-law exponent

ξXN. That is, people who are more patient (a lower

ρ), more willing to substitution consumption over time (a higher elasticity of intertemporal substitution,

1/γ), and/or less likely to die (a lower

λ) accumulate more wealth and move into the right tail of the wealth distribution.

Average wealth is

The equilibrium interest rate,

r, solves

where

E(Y) is given by [], and

E(X) is given by []. The equilibrium interest rate satisfies

The left inequality in [] states that the equilibrium interest rate

r exceeds the larger

ρN+γNgN to ensure that savings motives are sufficiently strong for both groups so that they want to use Ramsey rules. An implication of this result is that the equilibrium interest rate

r>max{ρA,ρB}, in contrast to outcomes in refs. , , and models with infinitely lived agents. The right inequality in [] states that the equilibrium interest rate cannot be so high that it causes consumption for either group to grow at a rate

(r−ρN)/γN larger than the death/exit rate

λN. Otherwise, there is no stationary wealth distribution.

Group A as hand-to-mouth consumers.

Next, we turn to a situation in which one group of agents is financially constrained:

Now, agents in group

A with their high earnings growth

g, high discount rate

ρ, or low elasticity

1/γ want to front-load consumption enough to cause

Xt≥0 to bind, i.e.,

Xt=0 at all

t. That makes them into hand-to-mouth consumers forever. In equilibrium, agents in the other group cannot be hand-to-mouth consumers, and we must have

πB<1. Otherwise, there would be insufficient savings to support aggregate production, driving the marginal product of capital to plus infinity. The equilibrium interest rate has to be at a level where

πB<1, meaning that agents in group

B are financially unconstrained with optimal consumption functions that take the form of Ramsey rules.

Recall that X=0 for all agents in group A and that their mass is θ. People in group B all have positive savings. Therefore, the CDF for the wealth distribution has positive probability mass at X=0: ΦX(0)=θ and

In [],

YB(X) is the value of

Y that solves

X=XB(Y), where

XB(Y) is given by [] with parameter values for

N=B. and imply that the power-law exponent of wealth is

ξXB, where

ξXB is given by [] with

N=B.

Equilibrium average wealth is

The equilibrium interest rate,

r, solves [], where

E(X) is given in [] and

E(Y) is given in [].

The equilibrium interest rate satisfies the following restriction:

As group

A agents are hand-to-mouth, only parameter values for group

B appear in []. As in our baseline model with no ex ante heterogeneity, the equilibrium interest rate

r exceeds the subjective discount rate for the financially unconstrained type-

B agents (

ρB) by

γBgB, but the equilibrium consumption growth rate

(r−ρB)/γB cannot exceed death rate

λB, as required by the inequality on the right side of []. Otherwise, there is no stationary wealth distribution.

Consequences of Heterogeneous Discount Rates and Earnings Growth Rates.

In Tables 2 and 3, we display consequences of varying ρA. We hold all other parameters at the same values for the two groups: λA=λB=0.0167, gA=gB=1.11%, and γA=γB=2. When the subjective discount rate ρA is just slightly larger than ρB=5%, which means πA<1 holds (case 1), the equilibrium consumption rules for both groups are linear in wealth and earnings. We report these results in Table 2. The first row corresponds to the baseline case with no heterogeneity as ρA=ρB=5%. Therefore, r=7.5%, and we reproduce results from Table 1. By increasing ρA (e.g., to 5.4%) and keeping ρB=5%, type-A agents increase their consumption, and firms would want more capital if r were fixed at 7.5%, so the equilibrium interest rate has to increase (to 7.65%). As a result, a higher interest rate helps savers accumulate wealth, and, hence, wealth inequality widens, as indicated by a higher Gini coefficient ΓX, a lower power-law exponent ξXN, and a higher fractional inequality FIX.

| ρA | r, % | ΓY | ΓX | ξY | ξX | FIY | FIX |

| 5% | 7.50 | 0.50 | 0.90 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 0.46 | 0.56 |

| 5.2% | 7.59 | 0.50 | 0.91 | 1.51 | 1.29 | 0.46 | 0.60 |

| 5.4% | 7.65 | 0.50 | 0.97 | 1.51 | 1.26 | 0.46 | 0.62 |

| ρA | r, % | ΓY | ΓX | ξY | ξX | FIY | FIX |

| 5.45% | 7.67 | 0.50 | 0.97 | 1.51 | 1.25 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

| 6% | 7.67 | 0.50 | 0.97 | 1.51 | 1.25 | 0.46 | 0.63 |

As we continue to increase ρA to 5.45% (the first row in Table 3), consumption for group A continues to increase up to the point where πA=1, which implies XtA=0 for all agents in group A at t≥0. As a result, for markets to clear, the interest rate again continues to increase. Using [], we confirm this intuition: the equilibrium interest rate: r=ρA+gAγA=5.45%+1.11%×2=7.67%. Because the interest rate increased only 2 basis points as we increase ρA from 5.4% to 5.45%, wealth inequality increases only slightly. Finally, further increasing ρA does not change equilibrium outcomes because type-A agents are constrained. This is why the two rows in Table 3 are the same.

Outcomes displayed in Tables 2 and 3 corroborate results of ref. , which uses heterogeneous discount rates to generate an empirically plausible wealth distribution.

Tables 4 and 5 reports equilibrium consequences of varying gA. We keep other parameters identical for the two groups: λA=λB=0.0167, ρA=ρB=0.05, and γA=γB=2. When the earnings growth rate gA is not too high so that πA<1 holds (case 1), equilibrium consumption rules for agents in both groups are linear in wealth and earnings. We report these results in Table 4. The first row corresponds to the baseline case with no heterogeneity as gA=gB=1.11% and, thus, r=7.5%, and we recover results reported in Table 1. By increasing gA (e.g., to 1.3%) and keeping gB=1.11%, type-A agents increase their consumption, and firms would demand more capital (if r were fixed at 7.5%), so the equilibrium interest rate has to increase (to 7.67%). As a result, savers accumulate wealth at a higher interest rate, and wealth inequality widens, as witnessed by a higher Gini coefficient ΓX, a lower power-law exponent ξXN, and a higher fractional inequality FIX

| gA | r, % | ΓY | ΓX | ξY | ξX | FIY | FIX |

| 1.11% | 7.50 | 0.50 | 0.90 | 1.51 | 1.34 | 0.46 | 0.56 |

| 1.2% | 7.57 | 0.53 | 0.91 | 1.39 | 1.30 | 0.52 | 0.59 |

| 1.3% | 7.67 | 0.56 | 0.94 | 1.28 | 1.25 | 0.60 | 0.63 |

| gA | r, % | ΓY | ΓX | ξY | ξX | FIY | FIX |

| 1.39% | 7.78 | 0.60 | 0.97 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.68 | 0.68 |

| 1.5% | 7.88 | 0.64 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 0.73 |

| 1.6% | 8.06 | 0.68 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 0.91 | 0.82 |

As we increase gA to 1.39% (the first row in Table 5), consumption for group A increases up to where πA=1, which implies XtA=0 for all agents in group A at t≥0. As a result, for markets to clear, the interest rate again has to increase. Using [], we confirm this reasoning: the equilibrium interest rate: r=ρA+gAγA=5%+1.39%×2=7.78%. Earnings inequality and wealth inequality both also increase.

As we further increase gA from 1.39 to 1.6%, consumption for agents in group A no longer responds, as they are involuntarily constrained to be hand-to-mouth consumers for any gA satisfying 1.39%≤gA≤λA. As labor becomes more productive (higher gA), the firm’s demand for capital continues to increase (as capital and labor are complements). In equilibrium, the interest rate rises to 8.06% to restore equilibrium for the case where gA=1.6%.

A faster earnings growth rate increases both earnings inequality and the equilibrium interest rate r. Therefore, wealth inequality increases because savers accumulate wealth at a faster rate via a higher r. Thus, faster earnings growth generates larger earnings inequality and also larger wealth inequality. These outcomes are consistent with our baseline analysis with ex ante identical agents.

While inequality measures for earnings and wealth both increase with gA, whether wealth inequality is greater than earnings inequality for a given gA depends on how we measure inequality. When πA>1 in equilibrium, the Gini coefficient (i.e., two times the area between the 45° line and the Lorenz curve) and measures of tail fatness (e.g., the power-law exponent and the fractal inequality, FI) yield opposite answers.

Table 5 shows that the earnings distribution has a fatter right tail than does the wealth distribution when πA>1 in equilibrium. For example, when gA=1.6%, the power-law exponent for earnings is 1.04, which is lower than the power-law exponent for wealth, 1.09. The fraction of wealth owned by the top 10×u percent owned by the top u percent of people as u goes to zero, limu→0FIX(u), approaches 82%, which is already very large. However, this fractal inequality measure for earnings yields an even worse earnings inequality, FIY=91%, meaning that the fraction of earnings earned by the top 10×u percent that goes to the top u percent of people as u goes to zero, limu→0FIX(u)=0.91, which is larger than that measure for the wealth distribution.

Nevertheless, the Gini coefficient for earnings is much smaller than the Gini coefficient for wealth: ΓY=0.68 versus ΓX=0.98 for the case where gA=1.6%. This is because group A agents are at the bottom of the wealth distribution, with zero wealth, which substantially increases the Gini coefficient for wealth, while their being at the left tail evidently has no effect on the right tail of the wealth distribution. Indeed, the wealth-rich are people who have lower earnings growth, but who have lived long.

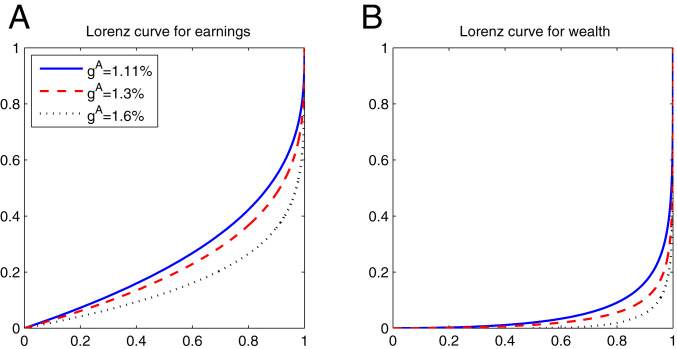

In Fig. 3, we plot the Lorenz curves for earnings and wealth in A and B, respectively. We see that as we increase gA, Lorenz curves for both earnings and wealth become steeper, and the Gini coefficient also increases.

Fig. 3.

Lorenz curves for cross-section earnings (A) and wealth (B). We set θ=0.5, gB=1.11%, λA=λB=0.0167, ρA=ρB=0.05, γA=γB=2, δ=0.06, and α=0.36.

Concluding Remarks

Our paper shares topics, but not models, methods, or findings, with ref. . Ref. bristles with fascinating claims about sources of wealth inequalities and presents them to a broad audience by deploying what ref. called “implicit theorizing” that can leave a technically inclined reader not knowing assumptions that make things fit together. Parts of his argument that lead him to emphasize an “r>g” condition as a cause of cross-section dispersion in wealth rest on an appeal to a single-agent growth model that has no wealth or income inequality.

Our model tightly links outcomes for individuals to macroeconomic outcomes that include the celebrated “r and g” variables that concerned ref. . A wedge between an equilibrium growth rate for wealth/savings, gtX≡X˙t/Xt and an earnings growth rate g at the level of individual people (not at the aggregate level) makes cross-section wealth more unequal than labor earnings.

Mathematics ties together equilibrium model outcomes: The same forces that make cross-section wealth more unevenly distributed and fatter-tailed than cross-section earnings also make an individual’s wealth grow at a higher rate than do her earnings. Firms’ demand for physical capital and an equilibrium growth rate for an individual’s savings that exceeds the growth rate of her labor earnings (gtX≥(r−ρ)/γ>g>0) imply that the equilibrium interest rate r exceeds the nonstochastic augmented golden-rule interest rate rramsey=ρ+γg.

Our paper shares tools, explicit theorizing, and some, but not all, goals with ref. , but differs in focus and details of the formal economic environments being modeled. They study effects of technical change and automation on an equilibrium wealth distribution and derive power laws like ones that we, too, find. Details about insurance arrangements and whether earnings processes are stationary or display growth differ between their framework and ours. What unites our project and theirs is our common reliance on the same mathematical tools for characterizing outcomes in heterogeneous-agent models cast in continuous time in closed forms. .

To obtain an enlightening and interpretable explicit solution for the wealth distribution, we have analyzed an admittedly unrealistic model with no shocks to labor earnings. Uninsurable shocks to labor earnings are, of course, important, so in ref. , we incorporate permanent uninsurable Brownian shocks to labor earnings. Quantitative outcomes in that model depend crucially on earnings growth volatility and precautionary savings. That model can be used to study how government tax and transfer policies affect equilibrium outcomes.