Edited by Eva Nogales, University of California, Berkeley, CA, and approved January 11, 2021 (received for review October 20, 2020)

Author contributions: K.N., K.W.M., L.-F.W., J.D.S., J.L., D.B., and C.J.R. designed research; K.N., K.W.M., L.-F.W., Z.Z., F.C., M.J.P., P.C.-H., P.Q., K.S., and K.D. performed research; K.N., K.W.M., L.-F.W., Z.Z., and M.J.P. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; K.N., K.W.M., L.-F.W., Z.Z., F.C., K.D., D.K., J.D.S., J.L., D.B., and C.J.R. analyzed data; and K.N., K.W.M., L.-F.W., J.D.S., J.L., D.B., and C.J.R. wrote the paper.

1K.N., K.W.M., and L.-F.W. contributed equally to this work.

While the current COVID-19 pandemic continues, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved only one drug against the virus—remdesivir. It is a nucleotide analogue inhibitor of the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase; favipiravir is another member of the same class. These nucleoside analogs were originally developed against other viral polymerases, and can be quickly repurposed against SARS-CoV-2 should they prove efficacious. We used cryoEM to visualize how favipiravir-RTP binds to the replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase and determine how it slows RNA replication. This structure explains the mechanism of action, and will help guide the design of more potent drugs targeting SARS-CoV-2.

The RNA polymerase inhibitor favipiravir is currently in clinical trials as a treatment for infection with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), despite limited information about the molecular basis for its activity. Here we report the structure of favipiravir ribonucleoside triphosphate (favipiravir-RTP) in complex with the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) bound to a template:primer RNA duplex, determined by electron cryomicroscopy (cryoEM) to a resolution of 2.5 Å. The structure shows clear evidence for the inhibitor at the catalytic site of the enzyme, and resolves the conformation of key side chains and ions surrounding the binding pocket. Polymerase activity assays indicate that the inhibitor is weakly incorporated into the RNA primer strand, and suppresses RNA replication in the presence of natural nucleotides. The structure reveals an unusual, nonproductive binding mode of favipiravir-RTP at the catalytic site of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, which explains its low rate of incorporation into the RNA primer strand. Together, these findings inform current and future efforts to develop polymerase inhibitors for SARS coronaviruses.

The COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic has spurred research into novel and existing antiviral treatments. The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp), crucial for the replication and transcription of this positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus, is a promising drug target for the treatment of COVID-19 (1). Nucleoside analogs, including remdesivir, sofosubivir, and favipiravir (T-705), have been shown to have a broad spectrum of activity against viral polymerases (2), and are being trialed against SARS-CoV-2 infections (34–5). Recent results of the World Health Organization Solidarity clinical trials indicate that remdesivir, hydroxychloroquine, lopinavir, and interferon treatment regimens appeared to have little or no effect on hospitalized COVID-19 patients, as measured by overall mortality, initiation of ventilation, and duration of hospital stays (6), so insight into the modes of action and mechanisms of current and future drugs for COVID-19 is increasingly important. The structures of the SARS-CoV RdRp (7), the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (8), and the SARS-CoV-2 polymerase bound to an RNA duplex (9), to RNA and remdesivir (10, 11), and to the helicase nsp13 (12) were all recently determined by electron cryomicroscopy (cryoEM). The suggested modes of action of favipiravir, a purine nucleic acid analogue derived from pyrazine carboxamide (6-fluoro-3-hydroxy-2-pyrazinecarboxamide), against coronaviruses comprises nonobligate chain termination, slowed RNA synthesis, and mutagenesis of the viral genome (13). Here we report the structure of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, comprising subunits nsp7, nsp8, and nsp12, in complex with template:primer double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) and favipiravir ribonucleoside triphosphate (favipiravir-RTP), determined by cryoEM at 2.5 Å resolution.

Favipiravir (T-705-RTP) was purchased from Santa Cruz; upon receipt, a stock solution of 50 mM T-705-RTP resuspended in 100 mM Tris, pH 7.5 buffer was aliquoted and stored at C. Phosphoramidites were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Link Technologies and used without further purification. Acetonitrile and other reagents (cap solutions, deblock solution, and oxidizer solution) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Primer Support 5G for A, G, C, or U (with loading at

Mass spectra were acquired on an Agilent 1200 liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry system equipped with an electrospray ionization source and a 6130 quadrupole spectrometer (chromatography solvents: A, 0.2% formic acid in

A synthetic gene cassette (GeneArts/Thermo Fisher) encoding a SARS-CoV-2 RdRp polyprotein, codon optimized for Spodoptera frugiperda, containing nsp5–nsp7–nsp8–nsp12 was cloned, with a C-terminal tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site double StrepII tag, into a pU1 vector for a modified MultiBac baculovirus/insect cell expression (14). The cell pellet was lysed in a buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 250 mM NaCl, 2 mM

The nsp7 and nsp8 were cloned into the NcoI–NotI, and BamHI–NotI sites of pAcycDuet1 (Millipore), and a pET28 vector modified to encode an N-terminal 6×-His-Sumo tag in frame with the multiple cloning site. Protein expression was pursued in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) Star cells cotransformed with the nsp7 and nsp8 plasmids. Cells were grown in ZY autoinduction media (15) at

The RNA template, 5′-rUrUrUrUrUrCrArUrArArCrUrUrArArUrCrUrCrAr- CrArUrArGrCrArCrUrG-3′, and RNA primer 5′-rCrArGrUrGrCrUrArUrGrUr- GrArGrArUrUrArArGrUrUrArU-3′ were prepared by solid-phase synthesis on an ÄKTA oligopilot plus 10 (Cytiva). RNAs were cleaved from the solid support by treating with 4 mL of a 1:1 mixture of 28% wt

Single-stranded primer and template RNAs (Fig. 1A) were resuspended in deionized and purified

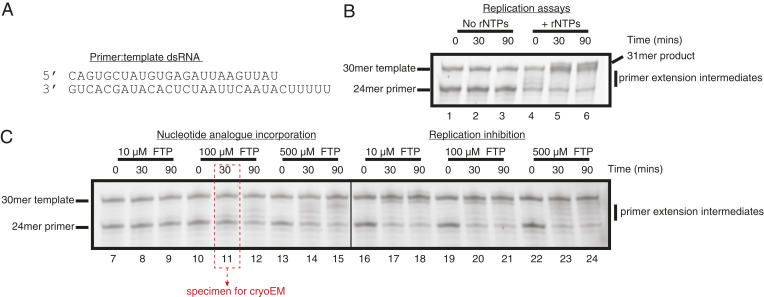

Reconstitution of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp activity and inhibition by favipiravir-RTP (FTP). (A) Sequence of the annealed primer (Upper):template (Lower) dsRNA duplex employed in biochemical assays. (B) Reconstituted SARS-CoV-2 RdRp extends the 24mer primer in the presence (lanes 4 to 6), but not the absence (lanes 1 to 3), of ribonucleotides (rNTPs). A 31mer product is present in lane 6, due to addition of a nontemplated base to the primer strand. (C) Favipiravir is weakly incorporated into the 24mer primer strand (lanes 7 to 15), and suppresses RNA replication by the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (lanes 16 to 24). Replication, nucleotide incorporation, and replication inhibition assays are representative results of four, six, and six technical replicates, respectively.

Purified apo-RdRp, assembled as above, was mixed immediately after purification with annealed dsRNA, resuspended in

All assays (Fig. 1 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) were performed at room temperature in assembly buffer. Reaction conditions were designed to approximate, as closely as possible, those employed in production of vitrified electron microscopy (EM) grids. For primer extension assays, 6

The 20% polyacrylamide, 8 M urea gels (0.75 mm thick, 20 cm long) were run at 15 W in Tris–borate–EDTA buffer for 2 h. The RNA gel was stained using SYBR Gold Nucleic Acid Gel Stain (Invitrogen). Fluorescence imaging was performed using an Amersham Typhoon imager (Cytiva).

The complex, prepared as described above, was used at a concentration of 1.3 mg/mL for preparing cryoEM grids. All-gold HexAuFoil grids with a hexagonal array of 280-nm-diameter holes, 700-nm hole-to-hole spacing, and 330 Å foil thickness were made in-house, and plasma was treated as described in ref. 16. Graphene was grown by chemical vapor deposition, transferred onto all-gold UltrAuFoil R0.6/1 grids (QuantiFoil), and partially hydrogenated following a previously described procedure (17). Grids were rapidly cooled using a manual plunger (18) in a

We acquired electron micrographs from four grids: three HexAuFoil grids (total 52,881 multiframe micrographs) and one partially hydrogenated graphene-coated grid (11,096 multiframe micrographs) (Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Table S1). Other surfaces that were screened during initial specimen preparation included graphene functionalized with amylamine or hexanoic acid and graphene oxide, none of which improved the orientation distribution or yielded two-dimensional (2D) classes indicating degradation of the complex more severe than due to the air–water interface alone. Thus, they were not included in the dataset for high-resolution reconstruction. The high density of foil holes on the HexAuFoil grid, combined with fast imaging by aberration-free image shift and a fast, direct-electron detector (Falcon 4, 248 Hz), allowed us to acquire more than 200 micrographs per hour for 14 consecutive days. The number of micrographs that can be acquired from a single HexAuFoil grid is limited only by the ice contamination rate in the vacuum of the electron microscope, rather than by the number of holes on one grid, even with the fastest available data collection setups.

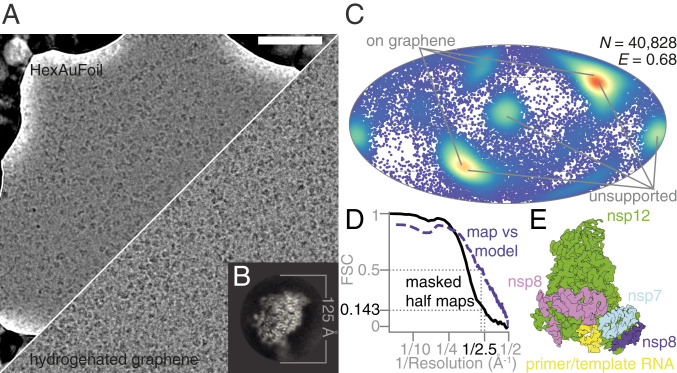

Electron cryomicroscopy of RdRp complexes in the presence of RNA and favipiravir-RTP. (A) Electron cryomicrographs of the reconstituted complexes in unsupported ice (HexAuFoil grid, Upper), and on hydrogenated graphene (Lower) were used for structure determination. (Scale bar, 500 Å.) (B) This 2D class average from the images of the complex, containing RNA, corresponds to the most frequent orientation of the particles in the thin film of vitreous water. (C) The orientation distribution, with efficiency,

All data were processed in RELION 3.1 (20), using particle picks imported from crYOLO 1.5 (21) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) with manual retraining of the model. After four rounds of 2D classification, it was clear that the specimen adopted a preferred orientation (Fig. 2B), as previously reported (9). The initial model for 3D refinement was obtained by low-pass filtering a published map of the complex with remdesivir (Electron Microscopy Data Bank accession code EMD-30210) (10) to 20 Å. The uniformity of the particle orientation distribution and the isotropy of the final 3D reconstruction were improved by combining data from HexAuFoil and partially hydrogenated graphene-coated UltrAuFoil EM grids (Fig. 2C). After three rounds of 3D classification, we obtained a 2.5 Å resolution isotropic map of the full complex from 40,828 particles (Fig. 2 D and E). A different set of 140,639 particles produced a 2.5 Å resolution map of the nsp12 subunit alone. The remaining 99% of the particles were discarded, as these corresponded to either the overrepresented view of the nsp12 subunit alone or to structurally heterogeneous complexes that did not align to high resolution.

Optical aberrations were refined per grid, the astigmatism was refined per micrograph, and the defocus was refined per particle. Particle movement during irradiation was tracked separately for the graphene and the HexAuFoil datasets, using Bayesian polishing (22). The dataset on graphene shows typical beam-induced motion at the onset of irradiation, whereas this movement is eliminated by the use of the HexAuFoil grids, which provided superior data quality, especially at the onset of irradiation, when the specimen is least damaged. Of the particles contributing to the final 3D refinement, 80% originated from the HexAuFoil grids, and 20% from the partially hydrogenated graphene grid. This was necessary to improve the particle orientation distribution: The efficiency,

To confirm the integrity of the assembled nsp7–nsp8–nsp12 SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complexes, we first performed primer extension activity assays. Consistent with prior publications, we observed efficient primer extension in the presence of natural ribonucleotide triphosphates (rNTPs) (Fig. 1 A and B, lanes 4 to 6 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1) (891011–12). Having verified the activity of the reconstituted RdRp, we then investigated the ability of the enzyme to incorporate favipiravir-RTP into the primer strand. In contrast to natural rNTPs, favipiravir-RTP appears to be a comparably poor substrate, with a low fraction of primer extension observed over the range of experimental conditions tested (Fig. 1C, lanes 7 to 15 and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The formation of larger RNA products observed at later time points (in particular, lanes 12 and 15) must arise through promiscuous base pairing with both uracil and cytosine in the template strand, and is consistent with the reported mutagenicity of favipiravir toward viral genomic RNA in vivo (13, 28, 29). Still, the incorporation efficiency (assessed by the amount of fully extended RNA) of favipiravir is less than that of rNTPs at the same concentration (500

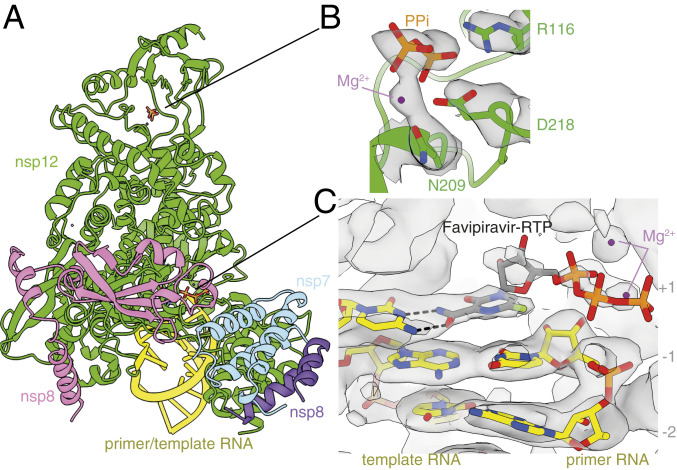

To investigate the structural basis of this activity, we determined the structure of the nsp7–nsp8–nsp12 SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complex, in the presence of template:primer RNA and favipiravir-RTP, by cryoEM (Fig. 2 and SI Appendix, Figs. S2 and S3 and Table S1). The overall structure of the polymerase complex observed (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4), comprising one nsp12, one nsp7, two nsp8 subunits, and a template:primer RNA, is nearly identical to those previously described (9, 10). With 2.5 Å resolution, and the reduced effects of radiation damage afforded by movement-free imaging (16), the map we determined is suitable for unambiguous atomic model building. We resolved and modeled some additional density in the N-terminal nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase (NiRAN) domain of nsp12, including a pyrophosphate and a

Structure of the RdRp complex bound to dsRNA and favipiravir-RTP. (A) The overall structure of the complex is shown, colored by subunit, in the same way as in Fig. 2E. The black lines point to the approximate positions of the catalytic sites, displayed in B and C, where the coloring is by heteroatom, and the EM map is contoured in gray. (B) A pyrophosphate is present at the NiRAN catalytic site of the enzyme, and is coordinated by key conserved residues in this domain. (C) The template:primer RNA duplex is shown, along with favipiravir at the catalytic site (

We found that favipiravir and two catalytic

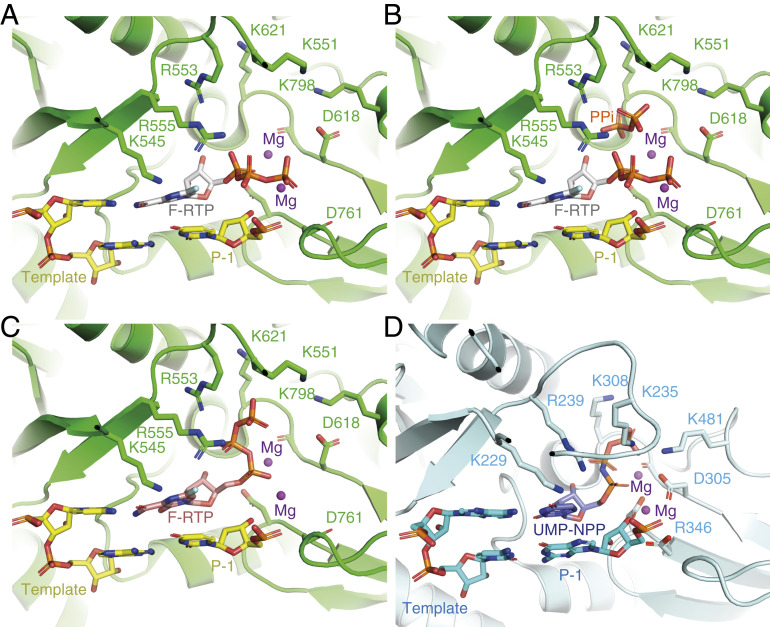

We observe signal for the RNA base pairs as synthesized, indicating no translocation of the RNA has occurred in the majority of the intact complexes during the incubation period of 30 min. This supports the interpretation that favipiravir stalls replication by noncovalent interactions at the active site, rather than by covalent incorporation into the replicating strand. Neither base stacking nor base pairing distances in the presence of favipiravir differ from those expected for natural nucleotides. In addition to base pairing with cytosine from the template strand, favipiravir is coordinated by Lys545 in the F1 domain of nsp12, which is positioned to accept hydrogen bonds from the nitrogen atom in the pyrazine ring or donate to the fluorine atom of the inhibitor, although, in both instances, the distances are long (3.4 Å and 3.7 Å, respectively), suggesting possible water-mediated contacts (Fig. 4A). These interactions are potentially functionally important because an arginine substitution of the equivalent residues in the chikungunya virus (CHIKV) and influenza virus H1N1 RdRps is responsible for their decreased susceptibility to favipiravir (2, 31). Two nearby arginines (Arg553 and Arg555) in the nucleoside entry channel are flexible, with no signal visible for the guanidinium group of Arg555 (Fig. 4A). The 2′ hydroxyl of the favipiravir nucleotide analogue forms a hydrogen bond to residue Asn691 of nsp12. A serine (Ser682) is positioned, as previously hypothesized (9), to play a role in coordinating the nucleotide for incorporation. The hydrophobic Val557 is stacked against the

In this study, we determined the cryoEM structure of favipiravir-RTP at the catalytic site of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp, in complex with template:primer dsRNA, and investigated the influence of this nucleotide analogue inhibitor on RNA synthesis in vitro. We observed that favipiravir-RTP is an inefficient substrate for the viral RdRp in primer extension assays, and propose that this is a consequence of a catalytically nonproductive conformation adopted by the drug in the polymerase active site. The nonproductive binding mode of favipiravir-RTP to the catalytic site of RdRp observed here explains the inefficient rate of covalent incorporation in primer extension assays. In the binding mode reported here, the

Coordination of favipiravir-RTP in the active site of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. (A) A nonproductive conformation of favipiravir-RTP (F-RTP), base paired to the P+1 nucleotide of the template strand, as shown, was observed in the cryoEM density map. For clarity, the primer strand is omitted, and only the P

One might hypothesize that pyrophosphate contributes to the slow rate of favipiravir-RTP incorporation by directing the triphosphate moiety of favipiravir-RTP into a nonproductive binding mode. However, pyrophosphate inhibition assays (SI Appendix, Fig. S7) indicate that pyrophosphate at concentrations between 10 and 500

While this manuscript was in preparation, another cryoEM reconstruction and an associated atomic structure of the RdRP:dsRNA:favipiravir-RTP complex became publicly available (EMD-30469, PDB ID code 7CTT) (32). This map is distorted along one direction, an artifact characteristic of anisotropic filling of Fourier space in the reconstruction. In contrast to the model described in this work, the alternative map and model suggest a productive conformation of favipiravir-RTP at the catalytic site. These two distinct states—the nonproductive favipiravir-RTP conformation described here, and the productive conformation, reported in ref. 32—may have captured two structural snapshots that account for the slow and inefficient incorporation of favipiravir into the growing RNA strand.

Multiple factors, including complex dissociation, denaturation at the air–water interface, and preferred orientation, impeded our initial attempts for high-resolution structure determination of this complex. We managed to circumvent these by acquiring a large cryoEM dataset and using a combination of HexAuFoil and partially hydrogenated graphene-coated UltrAuFoil EM grids. We make the complete dataset publicly available via the Electron Microscopy Public Image Archive (accession number 10517) in the hope that it will be useful for software development for handling large datasets of structurally heterogeneous cryoEM specimens. For now, cryoEM structure determination of this RdRp–RNA complex in combination with different inhibitors remains far from a routine task. Still, this and other published structures of the complex will aid rational drug design. In the interim, biochemical optimization of the stability of the complex might help yield a specimen that is more stable and randomly oriented in the thin layers of buffer used for cryoEM. This would then make it suitable for rapid structure determination among an array of candidate compounds. The need for a derivatized graphene surface to overcome the strong interactions with the air–water interfaces highlights the problem that surfaces present in cryoEM specimen preparation; further improvements in the specimen preparation process are still needed to enable the high throughput required for drug design and analysis.

The structure reported here suggests at least three possible directions for further efforts toward drug design against the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp. The first is modification of the favipiravir-RTP to bring the

We thank P. Midgley for enabling access to the Department of Materials Science & Metallurgy of the University of Cambridge for data collection during the pandemic, and S. Scheres for helpful advice during data processing. We also thank J. Grimmett and T. Darling of the Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) Scientific Computing and are grateful to S. Chen, G. Cannone, G. Sharov, A. Yeates, and B. Ahsan of the LMB Electron Microscopy Facility for technical assistance and enabling access to the microscopy facility during the pandemic. This work was supported by a Vice-Chancellor’s Award (Cambridge Commonwealth, European and International Trust) and a Bradfield scholarship (to K.N.). It was also supported by Medical Research Council Grants MC_UP_120117 (C.J.R.); MC_UP_1201/6 (D.B.), MRC U105184326, and Wellcome 202754/Z/16/Z (J.L.); MC_UP_A024_1009 (J.D.S.); and Cancer Research UK Grant C576/A14109 (D.B.).

The electron scattering potential map is deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with accession code EMD-11692, and the atomic model is deposited in the PDB under accession code PDB ID 7AAP. The complete, unprocessed cryoEM dataset is deposited in the Electron Microscopy Public Image Archive under code EMPIAR-10517.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32