Contributed by Lars Peter Hansen, October 26, 2020 (sent for review September 24, 2020; reviewed by Anmol Bhandari and Monika Piazzesi)

Author contributions: X.C., L.P.H., and P.G.H. designed research and wrote the paper.

Reviewers: A.B., University of Minnesota; and M.P., Stanford University.

1X.C., L.P.H., and P.G.H. contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

Prices in asset markets reflect a combination of investor beliefs and their risk preferences. Researchers, as well as policymakers, look to asset market data as a barometer of public beliefs. Such data are informative because investors must be compensated for exposure to macroeconomic shocks, and thus beliefs about future macroeconomic performance are encoded in asset prices. This paper develops a method informed by data and models to recover information about investor beliefs. Our approach uses information embedded in forward-looking asset prices in conjunction with asset pricing models. We entertain families of potential belief distortions bounded by a statistical measure of divergence. Additionally, our method allows for the direct use of sparse survey evidence to make these bounds more informative.

This paper develops a method informed by data and models to recover information about investor beliefs. Our approach uses information embedded in forward-looking asset prices in conjunction with asset pricing models. We step back from presuming rational expectations and entertain potential belief distortions bounded by a statistical measure of discrepancy. Additionally, our method allows for the direct use of sparse survey evidence to make these bounds more informative. Within our framework, market-implied beliefs may differ from those implied by rational expectations due to behavioral/psychological biases of investors, ambiguity aversion, or omitted permanent components to valuation. Formally, we represent evidence about investor beliefs using a nonlinear expectation function deduced using model-implied moment conditions and bounds on statistical divergence. We illustrate our method with a prototypical example from macrofinance using asset market data to infer belief restrictions for macroeconomic growth rates.

Prices in asset markets reflect a combination of investor beliefs and their risk preferences. Researchers, as well as policymakers, look to asset market data as a barometer of public beliefs. Derivative claims prices potentially enrich what we can infer about conditional probability distributions of future events, but events of interest often entail components of macroeconomic uncertainty for which there will be a paucity of information along some dimensions. Moreover, since a central tenet of asset pricing is that investors must be compensated for exposure to macroeconomic shocks that are not diversifiable, beliefs about future macroeconomic performance are of paramount importance to understanding asset prices.

To disentangle the contributions of risk aversion from beliefs, many empirical approaches in the last few decades have focused on models of investor preferences by assuming rational expectations. Using the implied moment conditions of the investor’s portfolio choice problem in conjunction with this restriction gives a directly applicable and tractable approach for estimating and testing alternative model specifications. This approach, however, often leads to risk prices in some time periods that are attributed to an arguably extreme level of investor risk aversion or a rejection of the model. Risk aversion and belief formulation are intertwined. Rational expectation as a model of belief formation is meant to be a simplifying approximation. It can serve as an elegant and powerful modeling choice when appropriate. In a complex environment, however, it can be challenging to make statistical inferences pertinent to forward-looking decision making. In such settings, we find the presumption that model-dwelling investors and entrepreneurs know the true data-generating process to be tenuous and worthy of relaxation. We are not alone in this view.

Some researchers have explored mechanisms that could account for this evidence via a different channel, namely beliefs which differ from rational expectations. It is sometimes argued, but typically not justified formally, that these alternatives are small departures from rational expectations. These “belief distortions” relative to rational expectations alternatively could reflect the lack of investor confidence about the assignment of probabilities to future events. This has been modeled and captured formally as ambiguity aversion or concerns about model misspecification.

This paper proposes a formal methodology for analyzing models that imply conditional moment restrictions where the restrictions are presumed to hold under a distorted probability measure. It extends a previous econometrics literature that represents the statistical implications of asset pricing implications as conditional moment restrictions under rational expectations. Rational expectations on the part of individuals or enterprises can be motivated by a law of large numbers approximation used to pin down the beliefs of these economic agents “inside the model.” Once we relax the rational expectations, there are typically many choices of investor beliefs that satisfy the conditional moment restrictions. Rather than imposing a specific alternative to rational expectations, we restrict the family of investor probabilities to satisfy discrepancy bounds, which gives us a way of relaxing the rational expectations hypothesis based on pushing back from a law of large numbers approximation. We then use the conditional moment restrictions along with statistical discrepancy bounds, to characterize families of probabilities that satisfy the conditional moment restrictions.

Our approach provides a version of “bounded rationality” when assessing empirical evidence. Not only are the bounds we deduce of direct interest; they also can be used as diagnostics for specific models of belief distortions. Additionally, we show how to include survey data on subjective beliefs. Such data are typically sparse and not sufficient to pin down full probabilistic characterizations of beliefs. Given these data limitations, we bound probabilities even when certain features of the data may be known through direct evidence.

A common way to represent a probability distribution of a random vector is through how it assigns expectations to functions of that random vector. Since we have multiple probability distributions in play, we represent our bounds by building what is called a “nonlinear expectation” that minimizes expectations over members of the family of probability distortions that we identify. This gives us a formal way to characterize properties of probability distributions that are consistent with model-implied conditional moment restrictions. The choice of minimization is essentially a normalization as we bound expectations of functions of observable variables as well as the negative of such functions. Given the flexibility in our choice of what functions of observables we use when forming expectation bounds, our analysis provides a rich characterization of implications for the belief distortions.

While we use asset pricing applications for motivation, our analysis is more generally applicable to economic models with forward-looking agents. These agents may be groups of individuals making investment or portfolio choices when facing production or financial opportunities that are exposed to uncertainty in different ways. Alternatively, they may be forward-looking enterprises, making decisions today that have important consequences for the future.

In summary, our methodology gives a way to extract information on investor beliefs from asset market and survey data pertinent for both external analysts and policymakers who are looking for evidence to gauge private sector sentiments. In addition, our computations provide revealing diagnostics for model builders that embrace specific formulations of belief distortions as is common in the behavioral economics and finance literatures.

Literature Review.

There is a long intellectual history exploring the impact of expectations on investment decisions. As was well appreciated by economists such as in refs. (12–3), investment decisions are in part based on people’s views of the future. Alternative approaches for modeling expectations of economic actors were suggested including static expectations, ref. 4’s extrapolative expectations, ref. 5’s adaptive expectations, or appeals to data on beliefs; but these approaches leave open how to proceed when using dynamic economic models to assess hypothetical policy interventions. A productive approach to this modeling challenge has been to add the hypothesis of rational expectations. Motivated by long histories of data, this hypothesis pins down beliefs by equating the expectations of agents inside the model to those implied by the data-generating distribution. This approach to completing the specification of a stochastic equilibrium model was initiated by ref. 6 and developed fully in ref. 7.

Recently there has been a renewed interest in alternative belief distortions within the asset pricing literature. See, for example, refs. 891011–12. Relatedly, since survey evidence on investor beliefs is typically rather sparse and not able to produce entire predictive distributions, refs. 13 and 14 fitted time series models to the observed beliefs that can be distinct from the actual data evolution. Our approach is different from these literatures, but complementary to them. We focus on the construction of the implied bounds for expectations for functions of the stochastic process of interest that could provide empirical targets of tests of parametric models of subjective beliefs fitted to time series.

There is similarity in motivation and overlaps in the methods we use to the study of robust optimization (see, for instance, refs. 15 and 16) and robust Markov chain modeling (see, for instance, ref. 17). But our is aim different. While the robust optimization research features decision makers that confront multiple probabilities, our perspective is that of analyst seeking information about the beliefs of economic decision makers from observed financial market data or survey data through the lens of a dynamic economic model.

Refs. 18 and 19 describe and implement econometric methods for confronting conditioning information under correct model specification under rational expectations, within a generalized method of moments framework. Refs. 20 and 21 give extensions of the measure of model misspecification proposed by ref. 22 to accommodate conditioning information. Similarly, the models we consider are misspecified under rational expectations. This misspecification is induced as it is in precursors (23, 24) by investor belief distortions (these two papers abstract from the role of conditioning information). Our innovation is to propose and justify a dynamic formulation with belief uncertainty that 1) accommodates conditioning and 2) uses the recursive structure of multiperiod likelihoods to characterize families of beliefs that are consistent with alternative divergence thresholds.

Outline of the Paper.

1. Asset Pricing with Distorted Beliefs introduces the framework we use for moment restrictions implied by an asset pricing model. 2. Data Generation and Probability Divergence specifies the probabilistic environment that underlies our computations and gives a dynamic version of the divergence with a built-in recursive structure. 3. Moment Bounds presents and justifies our recursive formulation of the functional equation used to compute the bounds along with some special cases that are of particular interest. This section provides a more complete characterization of the solution for the familiar relative entropy divergence and discusses the relation to results from large deviation theory. Finally, 3. Moment Bounds characterizes a nonlinear expectation as a way to represent the bounds on the subjective probabilities. 4. Illustration presents an empirical illustration of our methodology. 5. Bounding Other Probabilities shows how to apply our approach to extract information about the one-period, risk neutral measure and the long-term counterpart without assuming the existence of data on a complete set of Arrow–Debreu securities. Both of these probability measures are of interest in their own right. 6. Conclusions concludes.

1. Asset Pricing with Distorted Beliefs

In standard economic applications, moment conditions are justified via an assumption of rational expectations. This assumption equates population expectations with those used by economic agents inside the model. These expectations are therefore presumed to be revealed by the law of large numbers applied to time series data.

Let denote the underlying probability space and

A typical asset pricing example is as follows: Let

The underlying asset pricing equation is

A. Market Beliefs.

We allow for the beliefs that are revealed by the market to differ from the rational expectations beliefs implied by (infinite) histories of data. We represent what we call “market beliefs” by introducing a positive random variable

By using

The introduction of

Given our interest in the set of

Two classes of asset pricing models that have received considerable attention provide motivation for our analysis. One class allows for subjective beliefs to differ from those implied by rational expectations because of “market psychology.” Alternative models of expectations from behavioral finance imply alternative specifications of

Since the form of our pricing equation applies to investment or asset demand equations, there is a direct extension of our analysis to the case in which there are distinct classes of economic agents with potentially different subjective beliefs or concerns about ambiguity aversion.

B. Incorporating Survey Evidence.

When constructing our moment conditions, we could also include direct data on investor expectations to help inform the direction and magnitude of the subjective belief distortion from historical evidence. This would entail augmenting the moment conditions used to constrain beliefs to include the variable being forecasted minus the observed forecast all scaled by

Suppose we have data

Remark 1.1:

Time series of survey data are often shorter relative to data on returns or macroeconomic variables. This can be accommodated in our framework provided that there is sufficient time series variation for these data to add nontrivial incremental information to the analysis.

2. Data Generation and Probability Divergence

In this section we construct and use the dynamic counterpart to the statistical divergence measure. We focus initially on relative entropy as a measure of statistical divergence, a measure which frequently arises in the analysis of large deviations of stochastic processes with temporal dependence (see, for instance, refs. 27 or 28). While we use relative entropy as a starting point, we go much farther by extending the so-called

While the applications that interest us use Markov formulations, we relax this assumption to entertain non-Markov distortions. For this reason, we initially consider a stationary and ergodic formulation that nests stationary, ergodic Markov processes. This is the same environment used by ref. 29 to study bounds on statistical efficiency and ref. 30 to study testable implications of asset pricing models, both in the presence of conditional moment restrictions. The ref. 30 analysis imposes rational expectations in contrast to the analysis in this paper.

We start with a baseline probability triple

Let

A. Alternative Probabilities.

In what follows, we hold fixed the transformation

Form the product

Definition 2.1:

We say that

Definition 2.2:

The set

We presume that

B. Intertemporal Divergences

First consider the Kublack–Leibler divergence. Represent the expected log-likelihood ratio as a sum of contributions for each date by using the recursive structure of a relative likelihood:

Remark 2.3:

The relative entropy measure

Finite relative entropy restricts substantially the tail behavior of the probability distributions. For this reason we consider other divergences, but modified to exploit the recursive structure implied by the likelihood factorization. We use the conditional version of what is commonly called a

We use

Alternatively, there has been considerable interest in members of the Wasserstein class of divergences, including in the study of robust Markov chains and machine learning. Wasserstein divergences could also be used as conditional divergences that are averaged using the altered stationary probability

Remark 2.4:

Empirical likelihood methods (35, 36) use a divergence measure

Remark 2.5:

Using positive random variables,

Remark 2.6:

Our analysis assumes that the underlying processes are stationary under the alternative

3. Moment Bounds

We next present the recursive approach we use for computing probability bounds. To represent these bounds, we entertain a rich family of functions

In much of what follows, we aim to solve the following:

Problem 3.1.

It suffices to optimize over

A. Martingale Construction.

While we solve Problem 3.1 via recursive methods, as a precursor to this, we use a convenient martingale construction used in connection with the objective function. Suppose that for

B. Recursive Formulation

We use a rearranged version of Eq. 10 when posing the recursive formulation of the optimization problem.

Problem 3.2.

Find a pair

This problem is recognizable as a fixed point problem in

•the moment bound,

•the corresponding conditional moment,

•the implied divergence,

There are three features of Problem 3.2 that require further comment. First, the minimization problem includes “continuation-value” adjustments depicted by

C. Nonlinear Expectation

Consider now the set

Proposition 3.3.

The mapping

1)If

2)if

3)

4)

All four properties follow from the definition of

Remark 3.4:

While

Remark 3.5:

In our statement of Problem 3.2, we suppressed the dependence of the function

Remark 3.6:

For some applications, it is of interest to bound ratios of expectations of functions

D. Dual Problem

We show that the dual problem for the relative entropy divergence is equivalent to a principal eigenvalue problem. This gives a representation of the distorted measures that underlies the bounds and a revealing link to large deviation theory.

By a direct application of duality for

When the state space is not discrete, this eigenvalue problem can have multiple solutions. While there could be multiple solutions to this eigenvalue problem, the next result identifies the eigenvalue of interest.

Lemma 3.7.

When there are multiple positive eigenvalue solutions for a given

See SI Appendix, section B for a proof.††

Proposition 3.8.

Problem 3.2 with

Remark 3.9:

Our characterization is reminiscent of the results from large deviation theory for Markov processes. As in our analysis, large deviation theory studies an undiscounted limiting problem. See, for instance, refs. 28 and 32 for valuable treatises on large deviation theory.‡‡

A more substantive link to large deviations helps us interpret the relative entropy bounds that we input into our analysis. When using the empirical probability to detect potential departures from the baseline model, there is typically a positive probability that the empirical distribution mistakenly detects a departure. For a fixed criterion, the probability of this mistake becomes increasingly small as the sample size gets large with a well-defined rate characterized by large deviation theory. Under some additional regularity conditions, remarkably, the decay rate can be made to be arbitrarily close to the minimum relative entropy bound that we compute. Moreover, this theory computes excursions, represented probabilistically, that make the decay rate as small as possible. See SI Appendix, section D for an elaboration.

While we draw on insights from large deviation theory, our ultimate aim is quite different from that theory. Nevertheless, we find it revealing to compute both relative entropies and related Chernoff entropy as described, for instance, in refs. 42 and 43 as part of a sensitivity analysis.

E. Markov Specification

To proceed in a tractable way, we impose Markovian restrictions on the underlying data-generating processes. Specifically we presume that

Assumption 3.10.

Given this assumption, the

Problem 3.11.

Find a pair

While the primal problem “imposed” stochastic stability, it suffices to verify the stability of the process that we obtain as our candidate solution. Since it is Markovian, this restriction is satisfied when the process

4. Illustration

We illustrate these methods using a familiar asset pricing model with recursive utility investors as in refs. 44 and 45. While much of the asset pricing literature appeals to an arguably large risk aversion in conjunction with rational expectations when confronting data, we constrain risk aversion and instead explore belief distortions as an alternative expectation. We follow ref. 46 by allowing for market segmentation and avoid the direct use of consumption data. We then ask what implications asset market data have for predicted consumption growth rates.

Much of the macroasset pricing literature imposes risk aversion that is arguably large at least for some states of the macroeconomy. Refs. 47 and 48 give alternative rationales for substantially restricting the risk aversion coefficient. While we do not view as a settled issue what precise bounds should be imposed on risk aversion, we assume a unit risk aversion to feature the role of belief distortions when confronting asset pricing evidence. Our choice of unity is admittedly for convenience. As we will see, this choice leads to some particularly simple asset pricing implications.

Let

As ref. 45 notes, the consumption Euler equation for an investor implies

In our illustration, we draw on the literature that suggests returns can be predicted from dividend–price ratios. While there have been debates on how fragile this evidence is, we step aside from that discourse and take the predictability evidence at face value to illustrate our method. Given our direct use of dividend–price measures, we purposefully choose a very coarse conditioning of information and split the dividend–price ratios into three bins using the three empirical terciles. We take the dividend–price terciles to be a three-state Markov process. Dividend–price ratios are known to be persistent, and this will be evident in our calculations.¶¶

We implement our approach using quarterly data from 1954 to 2016. We use the return on the CRSP (Center for the Research on Security Prices) value-weighted index to proxy for the return on wealth. For asset returns, we use the return on a 3-mo treasury bill and the three Fama–French factor excess returns. We impose moment conditions for each return implied by Eq. 3, each scaled by three indicator functions for the terciles of the dividend–price ratio, giving a total of 12 moment conditions. All returns are converted from nominal to real returns using the deflator for nondurables consumption obtained from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. We then apply the methods described in 3. Moment Bounds to bound functions of the return on wealth as measured by the value-weighted return.

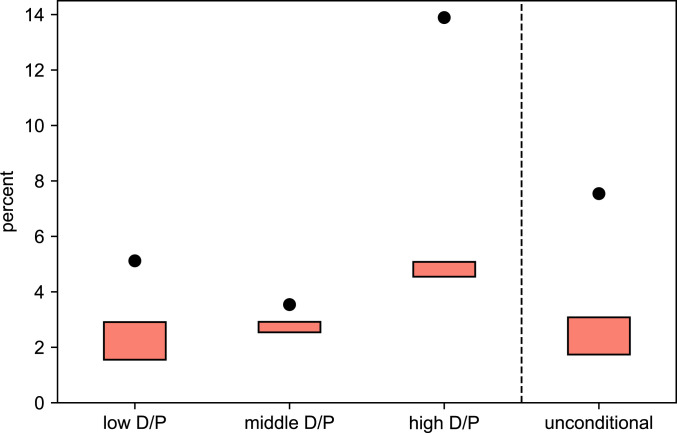

In Fig. 1, we report the bounds on the beliefs about the expected log return, which under the assumption of the unitary risk aversion coefficient are approximately proportional to the consumption growth rate belief when the subjective discount factor

Expected log market return. The

Interestingly, it is when we condition on the low value of the dividend–price ratio that we find the box with the largest height (biggest difference between the upper and lower bounds). Also, the bounds on the unconditional distorted expectations are very similar to those we found for the low dividend–price ratio. As a robustness check, we repeated these calculations for a quadratic conditional divergence and found only very modest differences (SI Appendix, section F).

Not only are conditional means distorted, but so are the transition probabilities as reported in Table 1. While the implied stationary probabilities are fairly evenly distributed over the three dividend states, essentially by construction, the minimal entropy probabilities down-weight substantially the high dividend–price ratio state and up-weight the low dividend–price state. The high dividend–price state, in particular, has a very small stationary probability under the minimum distorted stationary distribution. Consistent with this, the transition probabilities into this state are lower under the distortion and they are higher for exiting this state. The opposite happens for transitions in and out of the low dividend–price state. Thus, a hypothetical process that behaves in accordance with the minimum entropy distorted Markov transition matrix is likely to spend substantially more time in the low expected log-return state and much less time in the high expected log-return state. When we increase the relative entropy bound by 20%, the implied distorted transition matrices are quite similar to the implied transition matrix recovered by the minimizing relative entropy and depart from the empirical transition matrix in comparable ways.

| Empirical | Minimum entropy | |

| Transition matrix | ||

| Stationary probabilities |

An alternative approach would be to solve static versions of our analysis for each of the three different specifications of the conditioning information. Under this approach, there would be no reason for distorting the transition probabilities as the dynamical evolution of the conditioning information is ignored. Not surprisingly, this approach does lead to notable differences in bounds. The minimized entropy over the alternative configurations of the conditioning information using the undistorted transition probabilities is 0.047 in comparison to the much smaller 0.028 that we found using our method. We view belief distortions in the transition probabilities are of particular interest in behavioral models and in models with ambiguity aversion and see this as a virtue over methods that analyze the conditional problems separately.

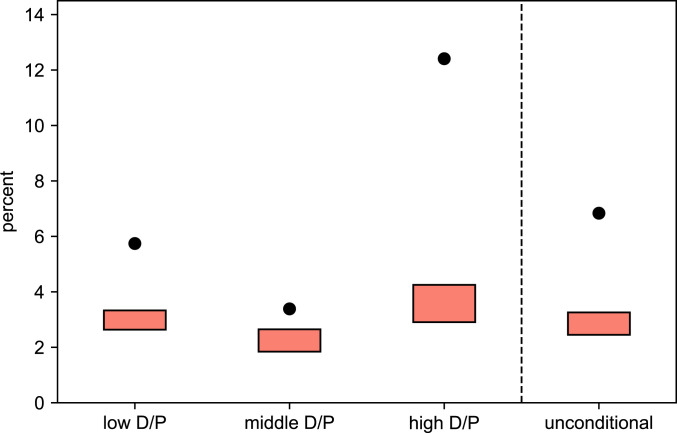

As we mentioned at the outset of this section, there is a substantial asset pricing literature that studies time-varying risk compensation, often appealing to high values of risk aversion. We illustrate how belief distortions can imitate large risk compensations. Thus, consider the bounds on the implied risk compensations when we restrict the risk aversion parameter to be one. We report proportional risk premium using the ex post real return on treasury bills,

Proportional risk compensations computed as

Finally, since our empirical method looks at other information from two other Fama–French excess returns, we also report bounds on other risk compensations that we included in our analysis. We convert the excess returns into returns by adding the gross returns on bonds. We report these findings in SI Appendix, section E. Again, the risk compensations are greatly reduced relative to the empirical counterpart, and in most instances they are less sensitive to conditioning information.

Putting aside the empirical debate on return predictability, we see two possible conclusions from these results. One possibility is that the statistical divergence (measured as relative entropy) for the distortions is high enough to challenge a bounded rationality view of the recursive utility model with a unitary risk aversion. The other possibility is that this divergence is defensible, in which case our dynamic implementation reveals the most statistically plausible distortions on the evolution of the dividend–price ratios. It remains a judgment call as to when the resulting statistical bounds we find here are implausible. Researchers that embrace rational expectations do not consider belief distortions, while behavioral finance researchers seldom consider the implied statistical divergence of their modeled beliefs. Neither practice uses tools for assessing statistical approximation as we have done in this paper. We view these computations as providing a valuable empirical complement to the assessment of specific models of belief distortions or ambiguity aversion. Moreover, we have noted how survey evidence can be included within our framework, and we view this as a potentially valuable extension of the illustration presented here.

5. Bounding Other Probabilities

We have motivated our analysis as a method for extracting expectation bounds for subjective beliefs or restricted “worst-case” beliefs that support valuation under ambiguity aversion. These same methods provide expectation bounds for two other probability measures that are of interest in asset valuation. These measures are the one-period risk-neutral probabilities and the long-term forward probabilities. While surveys cease to provide information about these probabilities, even sparsely observed asset values, as we assume here, are revealing. We now comment on how to apply our method for both of these applications.

A. Risk-Neutral Measure

Under risk-neutral pricing, the reciprocal of the gross one-period riskless return acts as a stochastic discount factor. Thus, in this case,

B. Long-Term Forward Measure

A substantively distinct, but mathematically related, literature studies the martingale decomposition of the stochastic discount factor. This decomposition expresses the stochastic discount factor as the product of a martingale component and a transitory component. The martingale component can be interpreted as a change of probability measures that imposes risk neutrality in valuation over long investment horizons. Refs. 53 and 54 show that the reciprocal of the gross holding-period return on a long-term bond is the stochastic discount factor net of a martingale component.

Since the work of ref. 54, the martingale component is referred to as the permanent component to the cumulative stochastic discount factor process. In providing a more formal mathematical characterization, refs. 40 and 41 find it more revealing to appeal to probabilistic characterization of this component. As emphasized by ref. 55, the probability measure associated with the martingale absorbs long-term risk adjustments for stochastically growing cash flows. This probability measure is the risk-neutral, forward measure that captures long-term risk–return tradeoffs.

Many structural models of asset pricing have stochastic discount factor processes with martingale components that dominate risk prices over long investment horizons. These components can reflect permanent shocks to the macroeconomy or forward-looking components to valuation. These components are present when investors have recursive utility preferences in which the intertemporal composition of risk matters or when they are averse to ambiguity in assigning probabilities to future events.

To relate this to our analysis, suppose that this martingale component is missing from the model specification. In such circumstances, ref. 53 justifies the use of the reciprocal of the gross holding-period return on a long-term bond,

Remark 5.1:

Ref. 57 gives conditions under which investor beliefs can be uniquely identified from asset prices. This identification hinges on a complete panel of state prices being available to the econometrician, as well as an implicit restriction that the stochastic discount factor process does not contain a martingale component. This latter restriction is violated in many standard asset pricing models (see ref. 55 for a discussion). More generally this identification reveals a forward probability measure that absorbs long-term growth rate risk. Our approach avoids the requirement of a complete set of state prices and can be used to identify sets of long-term forward probabilities that are consistent with asset pricing model restrictions and within a small deviation of rational expectations.

6. Conclusions

In this paper, we developed methods designed to extract information on investor beliefs from data on asset prices and investor surveys. Our approach presumes an econometric model of investors or enterprises that could be misspecified under rational expectations. We illustrated how limiting the statistical discrepancy between investor beliefs and rational expectations implies bounds on investors’ expectations. Formally, we represented this relationship through a nonlinear expectation function and derived its dual representation.

Going forward, we see two types of applications of our methods. Deducing market expectations about the future from forward-looking asset prices is a common practice in both the public and private sectors. But this is typically done either informally or by targeting so-called risk-neutral probabilities that confound beliefs and risk preferences. Our method provides a formal way to compute and represent information on investor beliefs constrained by a model of risk aversion along with a measure of statistical divergence.

Alternatively, we could use our approach to provide diagnostics for model misspecification under rational expectations. The bounds we deduce will help assess alternative models of subjective beliefs or ambiguity aversion. Implied belief bounds for small or moderate restrictions on the statistical divergence can give suggestive results for model builders as to how to repair potentially misspecified models. By comparing models of subjective beliefs or ambiguity aversion supported by belief distortions to the implied bounds, applied researchers could assess whether such departures from rational expectations could be easily discerned from limited data.

Future applications of our methodology could incorporate information from survey data on investor beliefs. One approach would be to include survey data directly as additional moment conditions when constructing expectation bounds. Another approach would be to compare survey-implied expectations to expectation bounds on the corresponding variables formed without using the survey data as information. The latter approach would provide a check on how plausible the survey data are as a representation of investor beliefs used in decision making.

While we focused on constraining probabilities based on intertemporal measures of divergence, these bounds could be used formally in the design of economic policy. For instance, refs. 58 and 59 pose dynamic policy problems in which a government policymaker fails to have precise knowledge of the beliefs of the private sector when designing a prudent course of action. While these papers explore what impact this imprecision could have on policy, our work looks more systematically at how to extract credible information about the beliefs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fernando Alvarez, Orazio Attanasio, Anmol Bhandari, Stéphane Bonhomme, Tim Christensen, Jim Heckman, Leo De Aparisi Lannoy, Winston Dou, Ralph Koijen, Marco Loseto, Yueran Ma, Andrey Malenko, Stefan Nagel, Diana Petrova, Monika Piazzesi, Eric Renault, Jose Scheinkman, Azeem Shaikh, Ken Singleton, Grace Tsiang, Harald Uhlig, and Xiangyu Zhang for helpful comments and suggestions. We gratefully acknowledge the research assistance of Han Xu and Zhenhuan Xie. We thank the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation (Grant G-2018-11113) for financial support.

Data Availability.

Computer code and computations with standard data sources have been deposited in Github at https://github.com/lphansen/Beliefs with computational details on the implementation. All study data are included in this article and SI Appendix.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

Robust identification of investor beliefs

Robust identification of investor beliefs