Edited by David M. Karl, University of Hawaii at Manoa, Honolulu, HI, and approved December 30, 2020 (received for review August 9, 2020)

Author contributions: E.J.Z. and N.M.L. designed research; E.J.Z. performed research; E.J.Z., B.B.C., and N.M.L. analyzed data; and E.J.Z., B.B.C., and N.M.L. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

Organic matter in the global ocean, soils, and sediments stores about five times more carbon than the atmosphere. Thus, the controls on the accumulation of organic matter are critical to global carbon cycling. However, we lack a quantitative understanding of these controls. This prevents meaningful descriptions of organic matter cycling in global climate models, which are required for understanding how changes in organic matter reservoirs provide feedbacks to past and present changes in climate. Currently, explanations for organic matter accumulation remain under debate, characterized by seemingly competing hypotheses. Here, we develop a quantitative framework for organic matter accumulation that unifies these hypotheses. The framework derives from the ecological dynamics of microorganisms, the dominant consumers of organic matter.

Organic matter constitutes a key reservoir in global elemental cycles. However, our understanding of the dynamics of organic matter and its accumulation remains incomplete. Seemingly disparate hypotheses have been proposed to explain organic matter accumulation: the slow degradation of intrinsically recalcitrant substrates, the depletion to concentrations that inhibit microbial consumption, and a dependency on the consumption capabilities of nearby microbial populations. Here, using a mechanistic model, we develop a theoretical framework that explains how organic matter predictably accumulates in natural environments due to biochemical, ecological, and environmental factors. Our framework subsumes the previous hypotheses. Changes in the microbial community or the environment can move a class of organic matter from a state of functional recalcitrance to a state of depletion by microbial consumers. The model explains the vertical profile of dissolved organic carbon in the ocean and connects microbial activity at subannual timescales to organic matter turnover at millennial timescales. The threshold behavior of the model implies that organic matter accumulation may respond nonlinearly to changes in temperature and other factors, providing hypotheses for the observed correlations between organic carbon reservoirs and temperature in past earth climates.

Heterotrophic organisms consume organic matter (OM) for both energy and biomass synthesis. Their activities transform much of it back into the inorganic nutrients that fuel primary production. Residual OM accumulates as large reservoirs in the ocean, sediments, and soils. Together, these pools store about five times more carbon than the atmosphere and play a central role in global biogeochemistry (1). Therefore, the dynamics of OM cycling and accumulation are key to understanding how the carbon cycle changes with climate (12–3).

Standing stocks of OM comprise a heterogeneous mix of thousands of compounds, many of which are uncharacterized, with concentrations ranging over several orders of magnitude (456–7). Compounds are often conceptually described in terms of a degree of “lability” that correlates with consumption rates, such that labile compounds have low abundances and short residence times in the environment (8, 9). In most biogeochemical models, OM degradation is dictated by simple rate constants, rather than explicit consumption by dynamic microbial communities (10, 11). Though significant progress has been made on integrating OM cycling with microbial community dynamics (1213141516–17), we still lack a mechanistic understanding of the ecological controls on OM and its accumulation.

Dissolved OM (DOM) cycling in the ocean has been studied for many decades, making this reservoir ideal for developing a mechanistic framework for OM accumulation. Three hypotheses have been invoked to explain DOM accumulation in the ocean: 1) “Recalcitrance”: Compounds may accumulate because they are relatively slowly degraded or resistant to further degradation by microorganisms (8, 9, 18, 19). This is consistent with observations, theory, and inferences of a wide range of consumption rates and compound ages in the ocean (2021222324–25), as well as in sediments and soils (910–11, 26, 27). 2) “Dilution”: The accumulation may represent the sum of low concentrations of many organic compounds, each having been diluted by microbial consumption to a minimum amount (28). This is supported by evidence that concentrating apparently recalcitrant DOM from the deep ocean fuels microbial growth (29). Modeling efforts have reconciled observed carbon ages with this mechanism and have interpreted the minimum concentrations as resource subsistence concentrations—the minimum concentrations to which populations can deplete their required resources (17, 30). 3) “Dependency on ecosystem properties”: The accumulation may result from a mismatch between OM characteristics and the metabolic capability of the proximal microbial community (e.g., the substrate specificity of enzymes) (313233–34). For example, the dispersal of microbial populations, which is controlled by the connectivity of the environment and which may manifest as a stochastic process (35), can allow for intermittent or sporadic OM consumption events (32, 34). In soils and sediments, some aspects of these hypotheses apply, while other processes also influence the accumulation of OM, such as diverse redox conditions and the physical and chemical dynamics of solid organic particles and mineral matrices.

Here, we investigate why OM accumulates using a stochastic model that simulates the complex dynamics of microbial OM consumption. We find that the mechanisms underlying each of the three above hypotheses come into play simultaneously in the model. We develop a quantitative definition of functional recalcitrance that depends on both the microbial community and the environmental context, in addition to substrate characteristics. We demonstrate the model’s ability to explain the accumulation of DOM in the ocean. Furthermore, because it is grounded in basic principles of microbial ecology, we suggest that this framework can also extend to soil and sediment environments. Finally, the threshold behavior of the recalcitrance indicator suggests nonlinear OM responses to changes in the environment.

A Mechanistic Model of OM Consumption.

We develop a model of OM consumption by microbial populations using established forms of equations for microbial growth and respiration (12, 36, 37). The model resolves multiple pools of OM () that are supplied stochastically and consumed by one or more microbial populations (

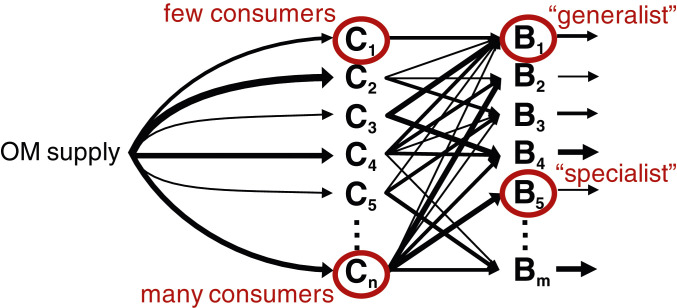

Schematic of the OM consumption model. Multiple OM pools

Because we expect the values of these growth and mortality parameters to vary widely among organisms and substrates, we sample all parameter values from uniform distributions over wide, plausible ranges (Table 1; SI Appendix, SI Text 1). We numerically integrate the equations forward in time, allowing the concentrations of OM pools to emerge from the ecological interactions. The dynamics presented here are robust across the parameter space, variations in the model structure, and variations in the number of OM pools and populations (SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and 3 and Figs. S2–S7). Sequential transformation of one OM pool to another due to incomplete oxidation gives qualitatively similar solutions (SI Appendix, SI Text 2), although this may increase compound age (17). We present results from simulations integrated for 10 y (Fig. 2).

| Parameter | Symbol | Value (range) | Units |

| Number of OM pools* | 1,000 | ||

| Number of populations† | 1,000 and 2,000 | ||

| Probability of presence | 0 to 1 | ||

| Total OM supply (all pools) | 0.1 | ||

| Potential supply (each pool) | |||

| Probability of supply | 0 to 1 | ||

| Maximum specific uptake rate | |||

| Half-saturation concentration | |||

| Yield (growth efficiency) | 0 to 0.5 | mol | |

| Quadratic mortality rate | 0.1 to 1 | ( | |

| Linear mortality rate | ml | 0 to 0.01 | |

| Loss rate |

Parameter values are assigned stochastically according to uniform distributions over the indicated ranges.

* Here, we illustrate two 10-member ensembles with 1,000 OM pools in each individual model, giving a total of 104 pools per ensemble. See SI Appendix, Fig. S3 for an individual model with 104 pools.

† The community consumption matrix dictates which populations consume each pool (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). See SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S7 for variations, including variations in the ratio of populations to pools from 2:1 to 1:1,000.

‡ Varied over a log rather than a linear range.

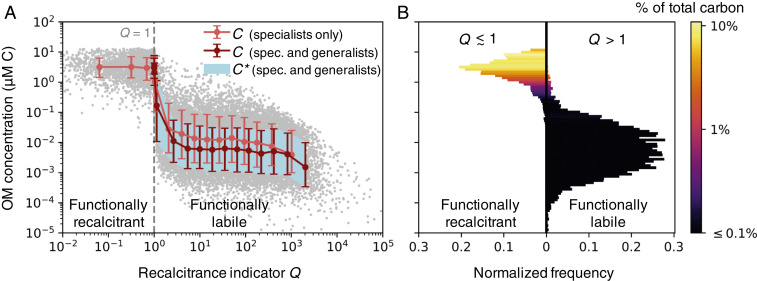

Simulated concentrations from the stochastic OM consumption model. (A) The modeled OM concentrations

The solutions reveal a bimodal distribution of OM concentrations (Fig. 2), implying a set of qualitatively distinct controls on OM accumulation. Whether or not the bimodality is discernible depends on the parameter distributions (SI Appendix, Fig. S13), as well as other sources and sinks not included in the model (e.g., photolysis). In the simple model, the majority of pools are depleted to relatively low concentrations (

Diagnosing Functional Recalcitrance.

We evaluate whether each OM pool equilibrates or accumulates in the model. Equilibration indicates that the pool can sustain a microbial population in the given environment, and we classify that pool as “functionally labile.” Otherwise, the pool accumulates in the environment, and we classify that pool as “functionally recalcitrant.” For example, we describe the population dynamics of specialist population

For the OM pool to equilibrate (

Most of the pools that accumulate to higher concentrations never equilibrate in the simple model. For these pools, the loss rates of all consuming populations match or exceed their maximum biomass synthesis rates. We consider these pools to be functionally recalcitrant. We can robustly define the threshold where pools transition from being functionally labile (depleted to

The recalcitrance indicator

In the environment, a functionally recalcitrant OM pool may accumulate or diminish at a rate dependent on production, consumption, and physical transport over time, or it can equilibrate due to an abiotic, concentration-dependent sink such as photolysis (8, 34). In the model version with many generalists,

Recalcitrance emerges as a community- and context-specific phenomenon that can change in time and space (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Critically, the recalcitrance indicator for each OM pool (

Unification of Hypotheses.

The three current hypotheses for DOM accumulation in the ocean—recalcitrance, dilution, and dependency on ecosystem properties—each explain aspects of the total amount of carbon in the model. Additional processes, such as mineral protection and diverse redox conditions of soils and sediments, can also be incorporated into the framework to modify it for these other systems. We may consider each hypothesis individually as a limit case for the formation of large organic carbon reservoirs in natural environments. Total organic carbon content is the sum of all OM pools. A traditional view of recalcitrance, focused on intrinsic qualities of the substrate or of the microbe–substrate-specific reaction, is represented in the model by the biomass yield

The degree to which each mechanism controls OM accumulation in different environments therefore depends on the parameter space that sets the population and OM characteristics. Here, we assume uniform distributions for these parameters using plausible ranges for the ocean (Table 1; SI Appendix, SI Text 1). These ranges will vary with the environment. For example, if stochasticity in population presence does not apply to a given sediment ecosystem, then probability of presence

Predicting OM Accumulation Patterns.

Our framework can help explain large-scale patterns in OM accumulation. Here, we use our model to understand the vertical structure of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in the ocean. Globally, DOC concentrations peak at the sea surface and approach a minimum at depth (Fig. 3A) (8). Since the stochastic model is not practical for multidimensional biogeochemical models, we utilize a reduced-complexity model analog that captures the essence of the stochastic model, resolving 25 aggregate pools. We incorporate this model analog into a fully dynamic ecosystem model of a stratified marine water column, where production and consumption of all organic and inorganic pools are resolved mechanistically as the growth, respiration, and mortality of photoautotrophic and heterotrophic microbial populations (SI Appendix, SI Text 6 and Fig. S14). The model is integrated for 6,000 y to quasi-equilibrium (SI Appendix, SI Text 6).

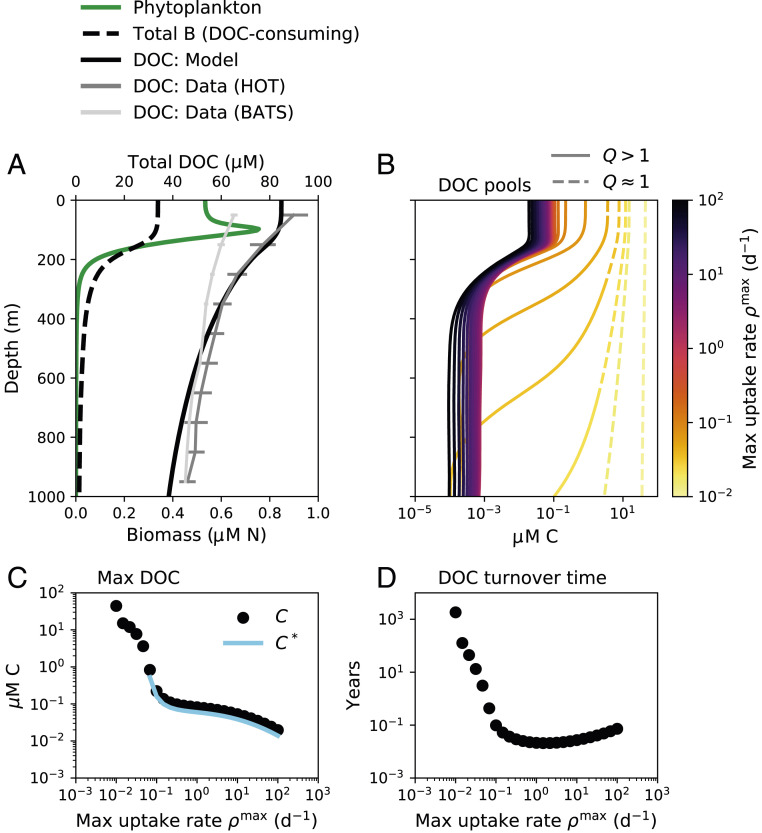

Marine ecosystem water-column model results showing the accumulation of DOC. (A) Phytoplankton biomass, total DOC-consuming biomass

Ecological interactions in the model result in characteristics typical of a marine water column (Fig. 3; SI Appendix, Fig. S15). Modeled DOC accumulates throughout the water column. Total DOC decreases smoothly with depth, with higher surface DOC transported to depth by vertical mixing (Fig. 3A). Most pools are depleted to subsistence concentrations throughout the water column (Fig. 3 B and C). One pool remains functionally recalcitrant throughout the entire water column due to its slow consumption rate (lightest yellow line in Fig. 3B), which is consistent with the observed homogenous composition of aged marine DOC (7, 48).

Many DOC pools in the model accumulate at the surface and become depleted at depths of 500 to 1,000 m. This transition is due to the increase in

Our framework may also be employed to investigate microbial control on OM in soils and sediments. The model can be adapted to incorporate the different characteristics of these environments. For example, here, we employ a simple parameterization for the supply of each OM class, but a sediment or soil model version could include more sophisticated descriptions of how the physics and chemistry of solid particles and mineral matrices impact the supply rate. Though Michaelis–Menten uptake kinetics do not apply to the enzymatically catalyzed degradation of polymeric organic compounds to monomeric compounds, the ecological principles of our framework should still hold (SI Appendix, SI Text 7). Indeed, we find that, even in its current form, the simple model captures a key observation of sediment OM: the proportional increase in OM decomposition rate with increased OM concentration (49) (SI Appendix, Fig. S16). This further demonstrates consistency with the predictions of established first-order kinetic decomposition models (12, 49). Our framework can also be used to explore the impact of more enzymatically diverse sedimentary communities relative to pelagic communities on OM accumulation (33) by altering the community consumption matrix to include a greater degree of generalist ability. Also, varying the yields or uptake rates with electron acceptors could incorporate diverse redox conditions into the model. A decrease in yield with a lower-quality electron acceptor may suggest that some types of OM are functionally labile when oxygen is available, but functionally recalcitrant in anoxic environments.

Implications.

Our model is consistent with the observations and previous sediment modeling results that the majority of the diverse types of OM are present at relatively low (

The water column model links the millennial timescales of OM turnover (24) to microbial consumption occurring on subannual timescales (Fig. 3D). Although OM transformation through a complex interaction network can also explain old carbon ages (17), slow turnover as an additional mechanism is consistent with inferences that the size of organic carbon reservoirs does not reach a steady state over geologic timescales (2). While our model is compatible with the dilution hypothesis, it also incorporates the other explanations for accumulation, and so it is consistent with a broader set of observations, including the compositional uniformity of ubiquitous recalcitrant classes (7, 48).

A key aspect of our framework is the threshold behavior of the accumulation. The threshold,

Consumption of recalcitrant OM depends on the rate of microbial processing, which increases with temperature. If other factors remain constant, the model predicts that less OM accumulates at higher temperatures (SI Appendix, SI Text 3 and Fig. S10C). Indeed, the loss of soil OM is a likely positive feedback to current warming (53). The framework here additionally suggests that a decrease in OM with warming may be nonlinear due to some OM pools crossing the threshold from functionally recalcitrant to functionally labile (SI Appendix, Fig. S10c). This may help to understand the correlations between temperature and organic carbon reservoirs in past earth climates, such as increased ocean carbon burial, “inert” soil carbon reservoirs, and perhaps marine DOC during glacial periods (54, 55). Temperature-driven nonlinearity may also constitute an explanation for the 10-fold higher microbial utilization rates of DOC in the warmer deep Mediterranean compared to the colder deep open ocean (56). Using this framework to quantitatively predict changes in organic carbon reservoirs with current increases in global temperature will require accurate estimates of microbial community loss rates, as well as an understanding of how temperature will impact both microbial rates and the diversity of the community.

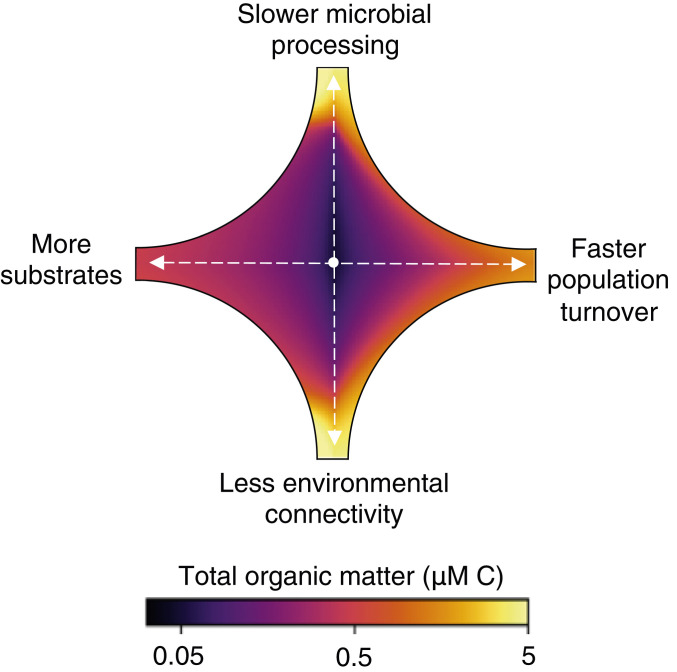

We identify a set of controls on OM accumulation and turnover rooted in the complexity of microbial ecosystems. Previously disconnected hypotheses for OM accumulation, including the many mechanisms giving rise to functional recalcitrance, are subsumed within one framework. OM concentrations are mediated by the characteristics of substrate–microbe interactions, the heterogeneity of organic substrates, microbial community dynamics, and the ecological and biogeochemical diversity set by the connectivity of the environment (Fig. 4). The model is consistent with a comprehensive set of observations and theory of OM concentrations, turnover rates, and ages. The framework can be used to quantify the degree to which each of the subsumed hypotheses explains OM accumulation in different environments and to develop testable hypotheses for how organic reservoirs change with the biogeochemical environment.

Controls on OM accumulation by microbial consumption. Starting from a representative, arbitrary concentration in the center, the change in total OM carbon is calculated for a 10-fold change in each of four parameters (i.e., two parameters vary in each quadrant): slower microbial processing via a reduced maximum uptake rate, faster turnover via an increased population-loss rate, less connectivity via a reduced likelihood of population presence, and more substrates (chemical diversity) via a greater number of OM pools.

Materials and Methods

Model Equations.

We describe microbial consumption and growth on pools of organic carbon. The model framework is sufficiently general to also account for inorganic nutrients and may be extended to account for the cycling of other elements. We model the uptake

Each population synthesizes biomass according to a growth efficiency for each pool (yield

Yield

Probability of Presence.

Observations show that community composition dictates the character of DOM remineralization in seemingly unpredictable ways (61, 62), and evidence supports localized sinks of deep DOM (32). To simulate this impact, we include a population presence–absence dynamic in the model. Each population is assigned an overall probability of presence

Consumption Matrix.

A consumption matrix dictates which populations consume which OM pools (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). We vary the specialist vs. generalist capabilities of the populations with respect to the number of OM pools taken up by each population (

Simulations.

In the simulations illustrated in Fig. 2, we resolve 1,000 OM classes and 1,000 or 2,000 pools of biomass: a model version with 1,000 specialists, and a model version with the 1,000 specialists and an additional 1,000 with a range of generalist ability. Results with the latter 2,000 pools are similar to a model with only the 1,000 generalists. For each experiment, we integrate the model forward in time for 10 y, until the pools that have the potential to equilibrate have equilibrated. The concentrations of many of the recalcitrant pools continue to increase over time (unless a concentration-dependent sink is added to the model). SI Appendix, Fig. S13 illustrates the resulting distributions of biomass concentrations, OM concentrations, and remineralization rates of the ensembles, which are consistent with observed and inferred distributions of OM characteristics, remineralization rates, and ages in the ocean, sediments, soils, and lakes (10, 212223242526–27, 6364–65).

In SI Appendix, SI Text 2 and Figs. S2–S7, we demonstrate the qualitative consistency of the solutions across variations of the model. All simulations support the conclusions presented. Solutions vary quantitatively, but not qualitatively, with variations in the generalist capabilities of the microbial populations, the number of OM pools resolved, the ratios of OM pools to populations resolved, the length of numerical integration, and the mode of uptake by the populations (additive consumption vs. switching over time to optimize growth). In the model version, where generalists switch their consumption over time (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), values of

Reduced-Complexity Model Version.

For the reduced-complexity model of OM consumption used in the marine ecosystem model, we collapse the complexity onto one master lability parameter—the maximum uptake rate—and we resolve fewer OM pools (

Marine Ecosystem Model.

The reduced-complexity model version is incorporated into a dynamic marine ecosystem model of a stratified vertical water column, where the production and consumption of all organic and inorganic pools are due to the growth, respiration, excretion, and mortality of microbial populations (SI Appendix, Fig. S14). Light and vertical mixing attenuate with depth. Two populations of phytoplankton convert dissolved inorganic carbon and nitrogen into biomass using light energy. Populations of microbial heterotrophs consume DOM (25 pools) and particulate OM (POM) (one pool), oxidize a portion of the carbon for energy, and excrete inorganic carbon and nitrogen as waste products. For simplicity, POM is resolved as one aggregate pool sinking at a constant rate. Total DOM is produced from POM degradation (due to the extracellular hydrolysis of POM) and the biomass loss of all populations. The model is a modified version of a published model in which carbon and nitrogen of the organic pools and the biomasses are each resolved independently (67). Parameter values are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. See SI Appendix, SI Text 6 for model equations and further detail.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge funding from the Simons Foundation: The Simons Collaboration on Principles of Microbial Ecology Grant 542389 (to N.M.L.) and the Simons Postdoctoral Fellowship in Marine Microbial Ecology (to E.J.Z.); National Environmental Research Council Grant NE-R015953-1 (to B.B.C.); and European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program Grant 820989 (to B.B.C.). We thank R. Letscher for providing the DOC data compilations; and N. Norris, J. McNichol, E. McParland, and the N.M.L. group for comments on the manuscript. The work reflects only the view of the authors; the European Commission and their executive agency are not responsible for any use that may be made of the information the work contains.

Data Availability.

Julia code for the stochastic OM consumption model and Fortran code for the marine ecosystem model are publicly accessible on GitHub (https://github.com/emilyzakem/OMconsumption) (68).

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

A unified theory for organic matter accumulation

A unified theory for organic matter accumulation