Edited by Nancy M. Reid, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, and approved November 18, 2020 (received for review July 23, 2020)

Author contributions: C.D., E.C., T.S., and M.G. designed research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

Science and engineering have benefited greatly from the ability of finite element methods (FEMs) to simulate nonlinear, time-dependent complex systems. The recent advent of extensive data collection from such complex systems now raises the question of how to systematically incorporate these data into finite element models, consistently updating the solution in the face of mathematical model misspecification with physical reality. This article describes general and widely applicable methodology for the coherent synthesis of data with FEM models, providing a data-driven probability distribution that captures all sources of uncertainty in the pairing of FEM with measurements.

We present a statistical finite element method for nonlinear, time-dependent phenomena, illustrated in the context of nonlinear internal waves (solitons). We take a Bayesian approach and leverage the finite element method to cast the statistical problem as a nonlinear Gaussian state–space model, updating the solution, in receipt of data, in a filtering framework. The method is applicable to problems across science and engineering for which finite element methods are appropriate. The Korteweg–de Vries equation for solitons is presented because it reflects the necessary complexity while being suitably familiar and succinct for pedagogical purposes. We present two algorithms to implement this method, based on the extended and ensemble Kalman filters, and demonstrate effectiveness with a simulation study and a case study with experimental data. The generality of our approach is demonstrated in SI Appendix, where we present examples from additional nonlinear, time-dependent partial differential equations (Burgers equation, Kuramoto–Sivashinsky equation).

The central role of physically derived, nonlinear, time-dependent partial differential equations (PDEs) in scientific and engineering research is undisputed, as is the need for numerical intervention in order to understand their behavior. The finite element method (FEM) has emerged as the foremost strategy to undergo this numerical intervention, yet when these discretized solutions are compared with empirical evidence, elements of model mismatch are revealed that require statistical formalisms to be dealt with appropriately (12–3). To address this problem of model misspecification, in this paper we introduce stochastic forcing inside the PDE and update the FEM discretized PDE solution with data in a filtering context.

Stochastic forcing is introduced through a random function within the governing equations. This represents an unknown process, which may have been omitted in the formulation of the physical model. For an elliptic linear PDE with coefficients , this can be expressed as

An area in which nonlinear and time-dependent problems are ubiquitous is ocean dynamic processes, where essentially all problems stem from a governing system of nonlinear, time-dependent equations (e.g., the Navier–Stokes equations). The ocean dynamics community has grown increasingly cognizant of the importance of accurate uncertainty quantification (5, 6), with many possible applications [e.g., rogue waves (7), turbulent flow (8)] for our proposed methodology.

An example process is nonlinear internal waves (solitons), which are observed as waves of depression or elevation along a pycnocline in a density-stratified fluid and are of broad interest to both the scientific and engineering communities (9101112–13). The classical mathematical model for solitons is the Korteweg–de Vries (KdV) equation (14):

Despite KdV being well studied (15) and widely applied (1617–18), its relative simplicity makes it prone to model mismatch. To compensate for this mismatch, we update the FEM discretized solution with observations in a filtering context. The resulting statistical FEM (statFEM) is shown using simulated and experimental data to

i)Approximate the data-generating process with a statistically coherent uncertainty quantification.

ii)Synthesize physics and data to give an interpretable posterior distribution.

iii)Utilize sparsely observed data to reconstruct observed phenomena.

iv)Enable the application of simpler physical models, updated with observations.

A Nonlinear, Time-Evolving Statistical FEM

A Gaussian process (GP),

Coefficients of Eq. 2 are assumed to be known, and we choose to update the numerical solution to the model, acknowledging that estimating

Discretizing Eq. 2 using finite elements in space with an implicit or explicit Euler method in time,† denote by

Unlike the elliptic example in the Introduction, for Eq. 2 the induced probability measure on the FEM coefficients is not available in closed form, and we present two approximations, based on the extended Kalman filter (EKF) and the ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF). The first linearizes about the current solution with the Jacobian

For the prior, the deterministic FEM solution is identically equal to the mean in the EKF approach. However we have found in numerical experiments that the EKF method, due to the use of the Jacobian, inflates the covariance at points of high gradient with reduction at points approaching near-zero gradient, when using large time steps. This does not occur with the EnKF approach.

| Algorithm 1: EKF algorithm |

| for |

| (Prediction step) |

| Solve |

| Estimate: |

| (Analysis step) |

Conditioning on Data.

Data

The filtered distribution

The initial conditions are known (i.e., they are given a Dirac measure). For time

We assume the parameters are independent across time [i.e.,

Conditioning procedure.

At time

i)Compute the tentative prediction step:

i)Maximize the EKF log-marginal posterior to estimate parameters:

i)where

i)Compute the full prediction step:

i)Complete the analysis step:

The prior

Simulation Study.

We condition on data generated from an extended Korteweg–de Vries (eKdV) equation with a cubic nonlinear term:

| Algorithm 2: EnKF algorithm |

| for |

| (Prediction step) |

| for |

| Solve |

| Compute |

| Estimate: |

| for |

| Solve |

| Compute |

| (Analysis step) |

| for |

setting

KdV is discretized following ref. 29, using

We assume

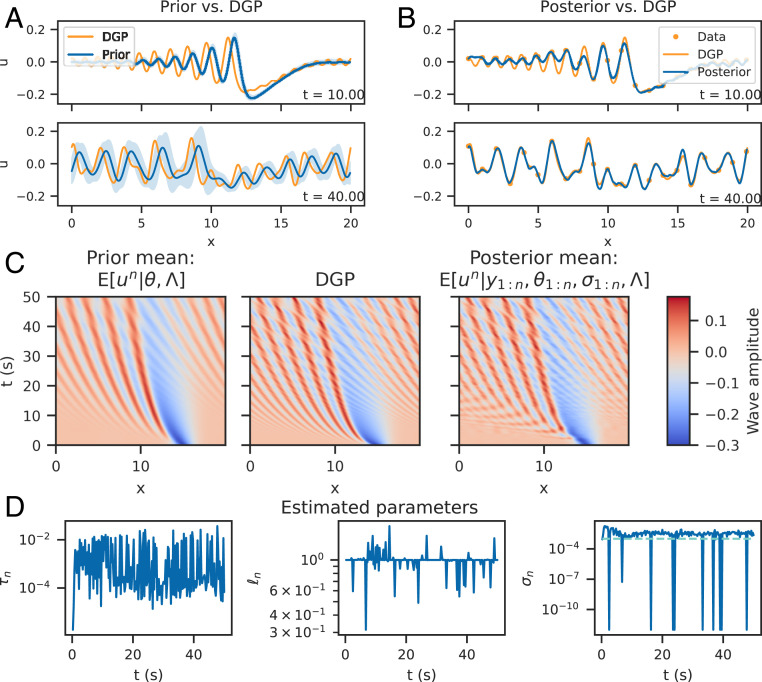

Simulation study results (using EnKF). A shows a prior solution with fixed hyperparameters

For a fixed set of hyperparameters

Fig. 1B shows that the posterior mean approximates the data-generating process, and the posterior uncertainty bounds have shrunk as a result of conditioning, indicating high certainty about the posterior mean values. Model discrepancy between the data and the statFEM solution has been corrected for. The space–time view of the posterior, shown in Fig. 1C, shows that the posterior has incorporated the complex soliton interactions in the data, not present in the prior.

Parameter estimates (Fig. 1D) indicate that the length and noise parameters are both stable, with the noise being slightly overestimated (i.e.,

Case Study: Experimental Data

We now apply the method to the experimental data collected in ref. 31. Experiments were conducted to study weakly nonlinear models for internal waves in lakes and consisted of generating internal waves in a two-layer stratified system, inside of a clear acrylic tank of dimensions

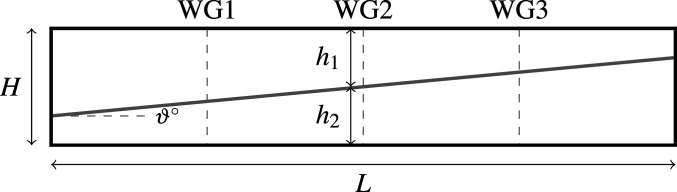

Data were recorded at three spatially equidistant locations in the tank using ultrasonic wave gauges (Fig. 2), taking measurements approximately every

Schematic diagram of the experimental apparatus. Wave gauges (WGs) are labeled WG1, WG2, and WG3, and the initial conditions are shown as a gray line, labeled with initial angle

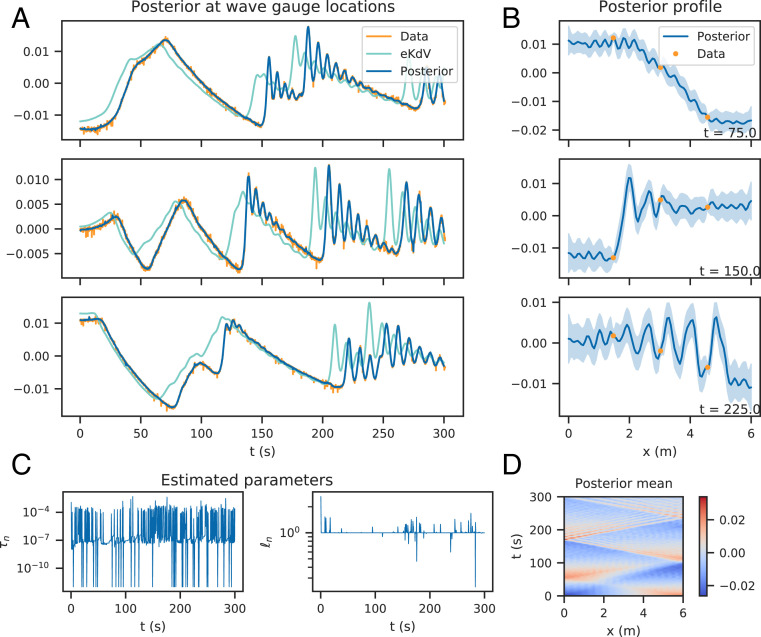

Experimental data results; posterior computed by the EnKF. A shows the observed data, the deterministic solution to the misspecified model, and the posterior mean at the wave gauges with 95% credible intervals up to time

Our physical model is an eKdV equation with—for computational simplicity—a linear dissipation term. We acknowledge that for laminar boundaries, other methods are preferred (31, 32). Including some form of dissipation is important as otherwise, the model becomes impractically mismatched by the end of the simulation. The eKdV is given by

Incorporation of reflective boundary conditions is done by solving the eKdV equation across the extended domain

The eKdV model does not capture the observed behavior exactly. The model waves have higher velocity than the observations, and model amplitudes are slightly larger than observed amplitudes. It is conjectured that this is due to misparameterization of dissipation, but in any case, the model is misspecified. Rather than estimating the eKdV parameters using inversion techniques, we sequentially update the model with observations to give the posterior

As before, we assume

We set weakly informative priors:

Posterior wave profiles are shown in Fig. 3B and demonstrate that given the data, the method is able to yield a sensible estimate for the underlying wave profile and is hence able to reconstruct the wave profile given sparse observations in space (Fig. 3D). Furthermore the provided uncertainty quantification is physically sensible, with bounds contracting about the data and expanding near the boundaries.

The hyperparameters,

Conclusions

We present a data-driven approach to the FEM that assimilates observations into nonlinear, time-dependent PDEs by embedding model misspecification uncertainty in the governing equations and sequentially updating the discretized equations with observations in a filtering context. Examples presented using the KdV equation (and the additional systems studied in SI Appendix) demonstrate that the method can approximate the data-generating process to give an interpretable posterior distribution, which reconstructs the observed phenomena.

This work sets the foundation for future studies of embedding data within FEM models. The use of the underlying Kalman framework permits the drawing upon of ideas from high-dimensional data assimilation, which for the systems studied here, were not needed. Techniques from Bayesian inversion can also be used to provide uncertainty quantification for physical quantities of interest, which will also allow for more accurate prediction. Finally, we believe that the development of similar methodology for alternate discretizations (e.g., spectral methods) could also be of great benefit, allowing for even broader application.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous referees whose suggestions greatly improved the manuscript. C.D. was supported by a Bruce and Betty Green Postgraduate Research Scholarship and an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship at the University of Western Australia. C.D. and E.C. were supported by Australian Research Council Industrial Transformation Research Hub Grant IH140100012. E.C. was supported by Australian Research Council Industrial Transformation Training Centre Grant IC190100031. M.G. was supported by Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Grants EP/R034710/1, EP/R018413/1, EP/R004889/1, and EP/P020720/1 and a Royal Academy of Engineering Research Chair.

Data Availability.

Data and code have been deposited on GitHub (https://github.com/connor-duffin/statkdv-paper).

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

Statistical finite elements for misspecified models

Statistical finite elements for misspecified models