Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America

Edited by Parag Pathak, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Paul R. Milgrom September 30, 2020 (received for review May 4, 2020)

Author contributions: Y.N. designed research, performed research, contributed new reagents/analytic tools, analyzed data, and wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) determine the fate of numerous people, giving rise to a long-standing ethical dilemma. The goal of this paper is to alleviate this dilemma. To do so, this paper proposes and empirically implements an experimental design that improves subjects’ welfare while producing similar experimental information as typical RCTs do.

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) enroll hundreds of millions of subjects and involve many human lives. To improve subjects’ welfare, I propose a design of RCTs that I call Experiment-as-Market (EXAM). EXAM produces a welfare-maximizing allocation of treatment-assignment probabilities, is almost incentive-compatible for preference elicitation, and unbiasedly estimates any causal effect estimable with standard RCTs. I quantify these properties by applying EXAM to a water-cleaning experiment in Kenya. In this empirical setting, compared to standard RCTs, EXAM improves subjects’ predicted well-being while reaching similar treatment-effect estimates with similar precision.

Today is the golden age of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs started out as safety and efficacy tests of farming and medical treatments, but have since grown to become the society-wide standard of evidence.

RCTs involve large numbers of participants. Between 2007 and 2017, over 360 million patients and 22 million individuals participated in registered clinical trials and social RCTs, respectively. Moreover, these experiments often randomize high-stakes treatments. For instance, in a glioblastoma therapy trial (1), the 5-y death rate of glioblastoma patients was 97% in the control group, but only 88% in the treatment group. In expectation, therefore, the lives of up to 9% of the study’s 573 participants depended on who received treatments. Social RCTs also often randomize critical treatments such as basic income, high-wage job offers, and HIV testing.

RCTs, thus, influence the fate of many people around the world, raising a widely recognized ethical concern with the randomness of RCT treatment assignment: “How can a physician committed to doing what he thinks is best for each patient tell a woman with breast cancer that he is choosing her treatment by something like a coin toss? How can he give up the option to make changes in treatment according to the patient’s responses?” (ref. 2, p. 1385).

To address this ethical concern, this paper develops an experimental design that optimally incorporates subject welfare. I define welfare by two measures: 1) the predicted effect of each treatment on each subject’s outcome; and 2) each subject’s preference or willingness to pay (WTP) for each treatment. My experimental design improves welfare compared to RCTs, while also providing unbiased estimates of treatment effects. The proposed design thereby extends prior pioneering designs that incorporate only parts of the welfare measures (345678–9). This proposal also complements clinical-trial regulations that safeguard patients from excessive experimentation (10), as well as adaptive experimental designs to most precisely estimate treatment effects (11).

I start by defining experimental designs as procedures that determine each subject’s treatment-assignment probabilities based on data about the two welfare measures. In practice, the experimenter may estimate the welfare measures from prior experimental or observational data, or ask subjects to self-report them (especially WTP).

I propose an experimental design that I call Experiment-as-Market (EXAM). I choose this name because EXAM is an experiment based on an imaginary centralized market and its competitive equilibrium (12, 13). EXAM first endows each subject with a common artificial budget and lets her use the budget to purchase the most preferred (highest WTP) bundle of treatment-assignment probabilities given their prices. The prices are personalized so that each treatment is cheaper for subjects with better predicted effects of the treatment. EXAM computes its treatment-assignment probabilities as what subjects demand at market-clearing prices, where subjects’ aggregate demand for each treatment is balanced with its supply or capacity (assumed to be exogenously given). EXAM, finally, requires every subject to be assigned to every treatment with a positive probability.

This virtual-market construction gives EXAM nice welfare and incentive properties. EXAM is Pareto optimal, in that no other design makes every subject better off in terms of expected predicted effects of and WTP for the assigned treatment. EXAM also allows the experimenter to elicit WTP in an asymptotically incentive-compatible way. That is, when the experimenter asks subjects to self-report their WTP for each treatment to be used by EXAM, every subject’s optimal choice is to report her true WTP, at least for large experiments.

Importantly, EXAM also allows the experimenter to estimate the same treatment effects as standard RCTs do. Intuitively, this is because EXAM is an experiment stratified on observable predicted effects and WTP, in which the experimenter observes each subject’s assignment probabilities (propensity scores). As a result, EXAM’s treatment assignment is random (independent from anything else), conditional on the observables. The conditionally independent treatment assignment allows the experimenter to unbiasedly estimate the average treatment effects (ATEs) conditional on observables. By integrating such conditional effects, EXAM can unbiasedly estimate the (unconditional) ATE and other effects, as is the case with any stratified experiment (14).

Power is also a concern. I characterize the statistical efficiency in EXAM’s ATE estimation. In general, the standard error comparison of EXAM and a typical RCT is ambiguous, as is often the case with comparing RCTs and stratified experiments. This motivates an empirical comparison of the two designs to confirm and quantify the power, unbiasedness, welfare, and incentive properties.

I apply EXAM to data from a water-cleaning experiment in Kenya (15). Compared to RCTs, EXAM turns out to substantially improve participating households’ predicted welfare. Here, welfare is measured by predicted effects of clean water on child diarrhea and revealed WTP for water cleaning. EXAM is also found to almost always incentivize subjects to report their true WTP. Finally, EXAM’s data produce treatment-effect estimates and standard errors similar to those from RCTs. EXAM, therefore, produces information that is as valuable for the outside society as that from RCTs.

Taken together, EXAM sheds light on a way economic thinking can “facilitate the advancement and use of complex adaptive (…) and other novel clinical trial designs,” a performance goal by the US Food and Drug Administration for 2018–2022. Experimental design is a potentially life-saving application of economic market design (16, 17).

EXAM

An experimental design problem consists of:

•Experimental subjects .

•Experimental treatments

•Each subject

•Each treatment

I assume

An experimental design specifies treatment-assignment probabilities

This paper investigates welfare enhancement with a design that I call EXAM. The steps for implementing EXAM are as follows.

1)Obtain predicted effects

2)Obtain WTP

3)Apply the following definition to the data from steps 1 and 2, producing EXAM’s assignment probabilities

Definition 1 (EXAM):

In the experimenter’s computer, distribute any common artificial budget

•Effectiveness-discriminated treatment pricing: There exist

This price is decreasing in treatment-effect prediction

•Subject utility maximization: For each subject

where

•Capacity constraints:

Let

A few remarks are in order. First, among the above steps, subjects only need to report their WTP

Welfare and Incentive.

EXAM is an enrichment of RCT, as formalized below.

Proposition 1 (EXAM Nests RCT).

Suppose that WTP and predicted effects are unknown or irrelevant, so that

Proposition 2 (Existence and Welfare).

There exists

Proposition 2 says that no other experimental design ex ante Pareto dominates EXAM in terms of the expected WTP for and predicted effect of assigned treatment (while satisfying the random-assignment and capacity constraints). In contrast, RCT fails to satisfy the welfare property, as it ignores WTP and predicted effects. I empirically quantify the welfare gap between RCTs and EXAM below.

Proposition 2 takes WTP

To investigate the incentive structure in EXAM, imagine that subjects report their WTP to EXAM. EXAM then uses the reported WTP to compute treatment-assignment probabilities. For the

EXAM approximately incentivizes every subject to report her true WTP, at least for large enough experimental design problems.

Proposition 3 (Incentive).

For any sequence of experimental design problems with any

Information

Despite the welfare merit, EXAM also lets the experimenter estimate treatment effects as unbiasedly as they would do in RCTs. To spell it out, here, I switch back to any given finite problem with fixed WTP and predicted effects.

Suppose the experimenter is interested in the causal effect of each treatment on an outcome

The experimenter would like to learn any parameter of interest

EXAM turns out to be as informative as RCT in terms of the set of parameters estimable without bias with each experimental design.

Proposition 4 (Estimability without Bias).

Under regularity conditions in

SI Appendix, if parameter

Many key parameters, such as the ATE and the treatment effect on the treated, are known to be estimable without bias with RCT and a simple estimator. Proposition 4 implies that these parameters are also estimable without bias with EXAM.

Corollary 1.

The ATE and the treatment effect on the treated are estimable without bias with EXAM.

I use the ATE to illustrate the intuition for and implementation of Proposition 4 and Corollary 1. Why is ATE estimable without bias with EXAM? The reason is that once it is constructed, EXAM is a particular stratified experiment stratified on observable WTP and predicted effects. EXAM, therefore, produces treatment assignment that is independent from (unconfounded by) potential outcomes conditional on predicted effects and WTP, which are observable to the experimenter:

Alternatively, empirical researchers may prefer a single regression:

Empirical Application

My empirical test bed for EXAM is an application to a spring-protection experiment in Kenya. Waterborne diseases, especially diarrhea, remain the second leading cause of death among children, comprising about 17% of child deaths under age five (about 1.5 million deaths each year). The only quantitative United Nations Millennium Development Goal is in terms of “the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation,” such as protected springs. Yet, there is controversy about its health impacts. Experts argue that improving source-water quality may only have limited effects, since, for example, water is likely recontaminated in transport and storage.

This controversy motivated researchers to analyze randomized spring protection in Kenya (15). This experiment randomly selected springs to receive protection from the universe of 200 unprotected springs. The experimenter selected and followed a representative sample of about 1,500 households that regularly used some of the 200 springs before the experiment; these households are the experimental subjects. The researchers found that diarrhea among children in treatment households fell by about a quarter of the baseline level. I call this real experiment the “original experiment” and distinguish it from EXAM and RCT as formal concepts in my model.

I consolidate the original experimental data and my methodological framework to empirically evaluate EXAM. Applying the language and notation of my model, experimental subjects are households in the original experiment’s sample. The protection of the spring each household uses at baseline is a single treatment

Given the estimates, imagine somebody is planning a new experiment to further investigate the same spring-protection treatment. What experimental design should she use? Specifically, which is better between RCT and EXAM? My approach is to use the estimated WTP

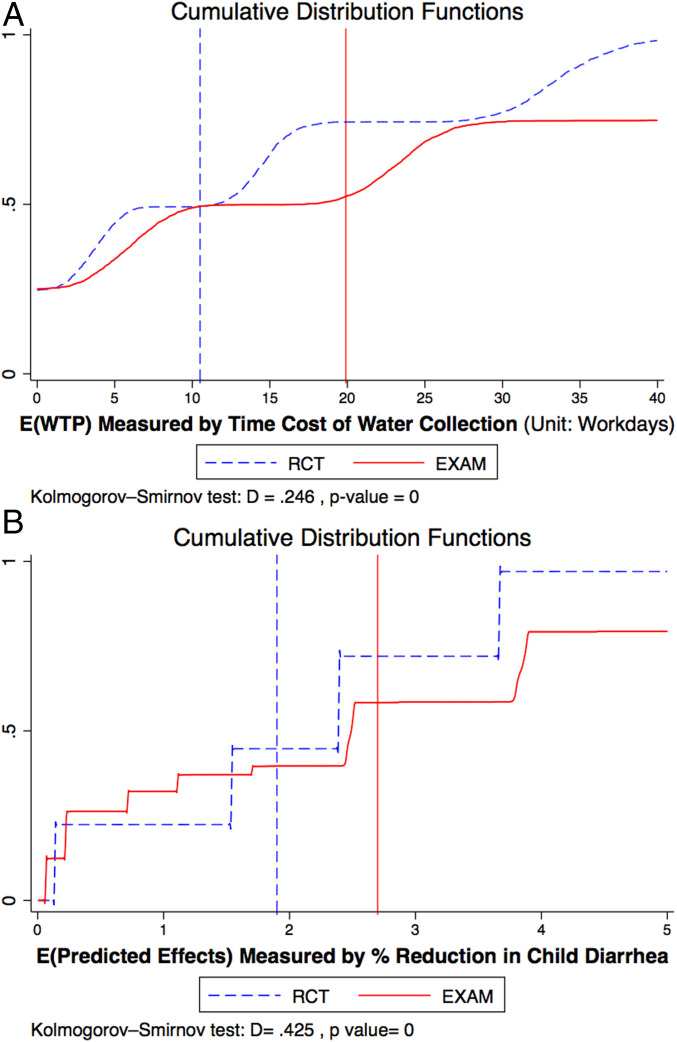

I start with evaluating EXAM’s welfare performance. I use EXAM’s treatment-assignment probabilities

I find that EXAM improves on RCT in terms of the welfare measures

EXAM vs RCT: Welfare. This figure shows the distribution of average subject welfare over 1,000 bootstrap simulations under each experimental design. A shows the average WTP for assigned treatments

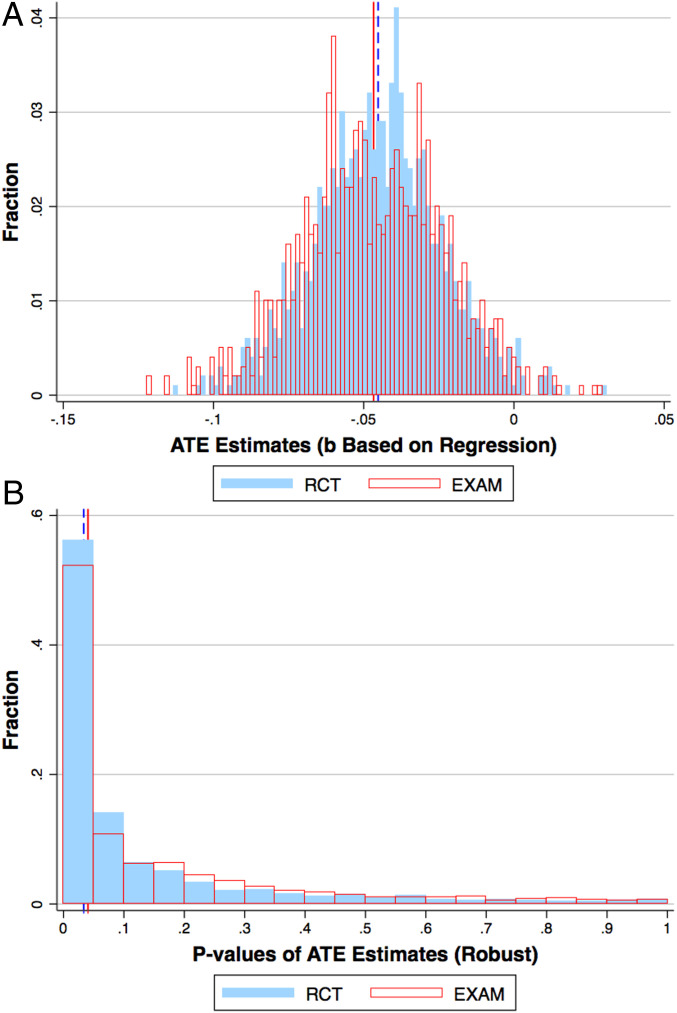

Data from EXAM also allow me to obtain more or less the same conclusion about treatment effects as RCT. To see this, I augment the above counterfactual simulation with ATE estimation as follows: I first simulate

Program evaluation with EXAM is as unbiased and precise as that with RCT. Fig. 2A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 plot the distribution of the resulting treatment effect estimates

EXAM vs RCT: Treatment-effect estimates. This figure compares EXAM and RCT’s causal-inference performance by showing the distribution of ATE estimates under each design. A shows the distribution of treatment-effect estimates

Perhaps more importantly, the distributions of

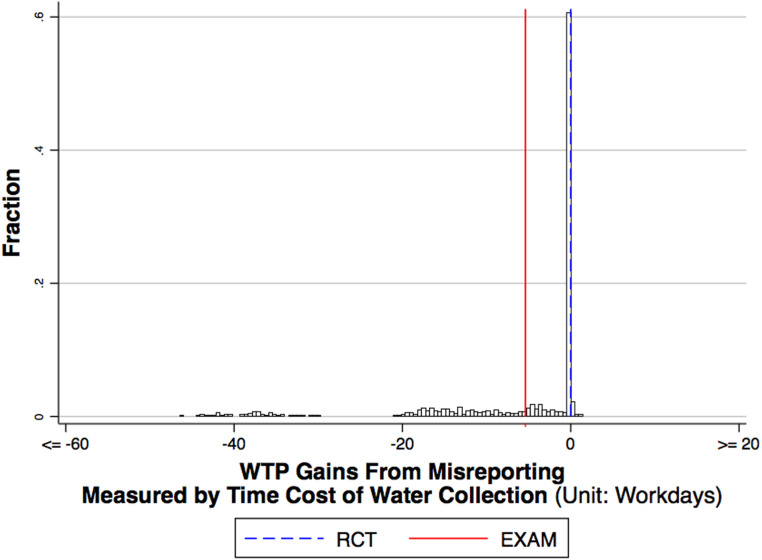

EXAM’s WTP benefits can be regarded as welfare-relevant only if EXAM provides subjects with incentives to reveal their true WTP. I conclude my empirical analysis with an investigation of the incentive compatibility of EXAM. I repeat the following procedure many times: As before, I simulate

EXAM vs RCT: Incentive (WTP manipulation

If the experimenter was only interested in the most precise estimation of treatment effects, a possible experimental design would be a stratified RCT that stratifies on the same covariates as EXAM. Another possible alternative is the stratified RCT of Hahn et al. (11).

Such designs may dominate EXAM in terms of the statistical efficiency in ATE estimation, though are inferior to EXAM in terms of welfare and incentive properties. In this sense, there is a tradeoff between information and welfare/incentive.

Conclusion

Motivated by the high-stakes nature of RCTs, I propose a data-driven experiment dubbed EXAM. EXAM is a particular stratified experiment derived from a hybrid experimental-design-as-market-design problem of maximizing participants’ welfare subject to the constraint that the experimenter must produce as much information and incentives as in RCTs (Propositions 2–4). These properties are verified and quantified in an empirical application where I simulate my design on a water-source-protection experiment. The body of evidence suggests that EXAM improves subject well-being with little information and incentive costs.

Data Availability.

Stata and cvs files data have been deposited in GitHub (https://github.com/aneesha94/EXaM-Public-folder).

References

1

2

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

Incorporating ethics and welfare into randomized experiments

Incorporating ethics and welfare into randomized experiments