- Altmetric

Within-host adaptation is a hallmark of chronic bacterial infections, involving substantial genomic changes. Recent large-scale genomic data from prolonged infections allow the examination of adaptive strategies employed by different pathogens and open the door to investigate whether they converge toward similar strategies. Here, we compiled extensive data of whole-genome sequences of bacterial isolates belonging to miscellaneous species sampled at sequential time points during clinical infections. Analysis of these data revealed that different species share some common adaptive strategies, achieved by mutating various genes. Although the same genes were often mutated in several strains within a species, different genes related to the same pathway, structure, or function were changed in other species utilizing the same adaptive strategy (e.g., mutating flagellar genes). Strategies exploited by various bacterial species were often predicted to be driven by the host immune system, a powerful selective pressure that is not species specific. Remarkably, we find adaptive strategies identified previously within single species to be ubiquitous. Two striking examples are shifts from siderophore-based to heme-based iron scavenging (previously shown for Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and changes in glycerol-phosphate metabolism (previously shown to decrease sensitivity to antibiotics in Mycobacterium tuberculosis). Virulence factors were often adaptively affected in different species, indicating shifts from acute to chronic virulence and virulence attenuation during infection. Our study presents a global view on common within-host adaptive strategies employed by different bacterial species and provides a rich resource for further studying these processes.

Introduction

Despite the advent of antibiotics, bacterial infections continue to cause millions of deaths world-wide (Lozano et al. 2012). These infections can range from acute, lasting a few days, to chronic, enduring over dozens of years. The host environment constitutes a unique ecological niche, introducing pathogens to a wide array of challenges, with antibiotic treatment and the host immune system being the most pronounced. Also, although the host metabolic environment is rich in nutrients, it exposes the bacteria to fierce competition with the local microbiota (Frydenlund Michelsen et al. 2016). Bacteria have been shown to evolve to meet these challenges over the course of the infection, developing mechanisms of immune evasion and even different forms of antibiotic resistance via genetic changes. Recent developments in high-throughput genomic technologies allow monitoring of genomic changes in small time frames during chronic bacterial infections (Didelot et al. 2016), enabling the tracing of genomic and genetic changes. Most studies in this field have focused on the evolution of opportunistic pathogens that shift between vastly different environments (Winstanley et al. 2016; Young et al. 2017; Chung et al. 2017). However, genetic changes are also prominent in other bacteria as they shift from initial to chronic infection (Marzel et al. 2016; Ley et al. 2019) and as they move between different subniches within the human host (Wylie et al. 2019).

Previous studies have demonstrated many mechanisms utilized by specific bacterial species to overcome the pressures and environmental changes they encounter (Alamro et al. 2014; Marvig, Sommer, et al. 2015; Didelot et al. 2016). These include loss of nonessential metabolic functions (Winstanley et al. 2016; Viberg et al. 2017), as well as tailoring of the expression and activity of metabolic pathways (Didelot et al. 2016; La Rosa et al. 2018). For example, Marvig et al. (2014) identified mutations in Pseudomonas aeruginosa that lead to reduced production of siderophores along with strong upregulation of systems for iron scavenging from heme. This phenomenon has been interpreted in the context of cheating behavior and subsequent upregulation of noncooperative iron uptake systems in bacterial populations (Andersen et al. 2015, 2018). It has the additional beneficial effect of downregulating the generally immunogenic siderophores (Wandersman and Delepelaire 2004).

Although previous studies have characterized genes that underwent loss of function or diversification during infection for specific pathogens and specific clinical contexts (Lieberman et al. 2011; Marvig, Sommer, et al. 2015; Brodrick et al. 2017), it is intriguing to find out whether different pathogens have converged toward similar strategies for their adaptation within the host environment. Here, we take advantage of the ample sequencing data of bacterial pathogens derived from prolonged infections to systematically address this question in large scale, investigating convergent evolution both within species and across species. Using a statistical framework, we trace the evolution of different pathogens within their hosts and assess the relationship between genes that underwent adaptive changes in the various pathogens. Although in many cases there are no orthologous relationships between the genes identified as undergoing adaptive changes in the various species, it is remarkable that often they are involved in parallel cellular processes, suggesting that different bacterial species exploit common strategies for their within-host adaptation.

Results

Constructing the Database

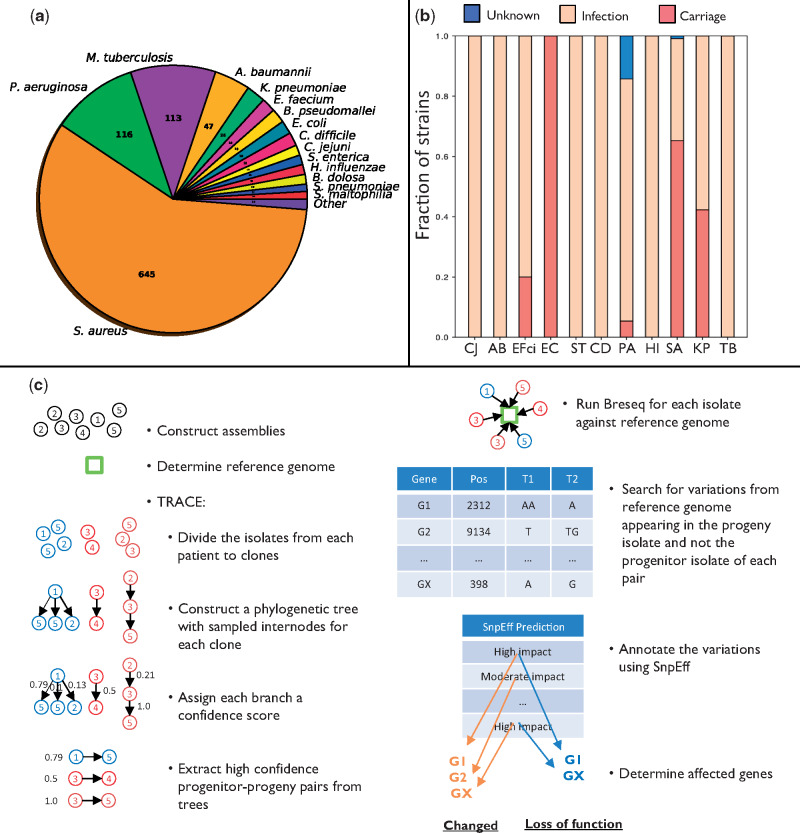

We compiled data from studies that conducted genome sequencing of an infecting pathogen in at least two time points during chronic infection or carriage (table 1). Carriage is defined here as colonization by a pathogen with no apparent symptoms over the entire period. The database includes 1,421 patients infected with 29 bacterial species encompassing 7,197 isolates (fig. 1a and supplementary fig. 1a and b, Supplementary Material online). We downloaded the sequencing reads of all isolates and assembled them into genomes in a uniform manner (Materials and Methods). To avoid biases due to species infecting only few patients, we focused on 11 bacterial pathogens for which ample data were available: Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB), Staphylococcus aureus (SA), Klebsiella pneumoniae (KP), Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium (ST), Escherichia coli (EC), Enterococcus faecium (EFci), Haemophilus influenzae (HI), Campylobacter jejuni (CJ), Clostridioides difficile (CD), and Acinetobacter baumannii (AB). The species we chose present a varied set of pathogens, including both opportunistic pathogens (PA, SA, KP, EC, EFci, CD, nontypable HI, and AB), and strict pathogens (TB, ST, CJ, and encapsulated HI), infecting the patients from a variety of sources including patient-to-patient transmission (TB, HI, CD, and some PA), contaminated food (CJ, ST), the hospital environment (PA, AB, and KP), and the patient’s own microbiome (SA, EC, EFci, and KP).

Overview of the study. (a) Number of strains of each bacterial species in the database. (b) Fraction of strains in each species isolated from patients undergoing different clinical scenarios (infection/carriage). PA, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis; SA, Staphylococcus aureus; KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; ST, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium; EC, Escherichia coli; EFci, Enterococcus faecium; HI, Haemophilus influenzae; CJ, Campylobacter jejuni; CD, Clostridioides difficile; AB, Acinetobacter baumannii. (c) Analysis pipeline for extracting genes undergoing either loss of function or any change (including loss of function) in a strain. We constructed assemblies for the different isolates using their respective sequencing reads and determined the reference genome closest to the isolates of each strain using QUAST. We utilized TRACE to assess the phylogenetic relations between the different isolates to extract progenitor–progeny isolate pairs (Materials and Methods). Breseq was then used to compare the sequencing reads of each isolate with the reference genome, and positions that differed from the reference genome and varied between the progeny and progenitor were determined. These variations were analyzed by SnpEff to define: 1) genes that underwent loss of function (based on high-impact variations appearing in the progeny isolate and not the progenitor isolate, leading, e.g., to deletion of a gene or to a stop codon); 2) changed genes (based on variations of moderate or high impact appearing in the progeny isolate and not the progenitor isolate, where moderate impact refers, e.g., to amino acid substitutions). The genes determined as undergoing loss of function make up a subgroup of the genes determined as changed.

Although the data include patients presenting one of two clinical scenarios, infection or carriage, for most species nearly all patients presented the same clinical scenario (either infection or carriage, fig 1b and supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online). For three species, SA, KP, and EFci, the data were derived from both patients with infection and patients with carriage.

Tracing the Phylogenetic Relationships between Different Isolates

During infection, the infecting bacteria present a genetically diversified population. Due to this within-host diversity, the isolates from each patient are in fact samples from a diverse population. This may introduce substantial sampling noise to the data: two isolates sampled at sequential time points do not necessarily have a progenitor–progeny relation, making the assessment of within-host evolution challenging. To reduce this sampling noise and trace the in-patient progenitor–progeny relationships of the isolates, we developed a two-level pipeline, termed TRACE (fig. 1c).

First, we assessed whether the isolates from each patient were derived from a monoclonal or polyclonal infection (Materials and Methods) and found that for most of the patients, all isolates were found on a single clade (supplementary fig. 1c, Supplementary Material online), hinting at a monoclonal infection. To prevent bias due to studies that did not choose the samples randomly, we repeated the above analysis excluding studies suspected to have such biases, reconfirming our previous observations regarding the dominance of monoclonality (supplementary fig. 1d, Supplementary Material online). We refer to all isolates from a single patient as representative of the same “strain” and to the ones that were found on the same clade as representative of the same “clone.”

Second, we developed an algorithm to construct the phylogenetic relationships between the isolates. Phylogenetic trees produced by previous construction methods include internal nodes representing inferred common ancestors, whereas in our data the ancestors were empirically sampled at previous time points. Accordingly, our algorithm for the construction of phylogenetic trees is parsimony-based and utilizes both inferred and sampled internal nodes for the inference of progenitor–progeny pairs (Materials and Methods). We assessed the accuracy of TRACE using simulated bacterial evolution (Worby and Read 2015) and discovered that it has high accuracy that is associated with the number of sampled isolates (supplementary fig. 2, Supplementary Material online). The time intervals between the different isolates were variable, being in the magnitude of days for some species and of years for others (supplementary fig. 3, Supplementary Material online).

Mutation Rates Are Higher at Earlier Stages of the Infection

We used the breseq pipeline (Barrick et al. 2014; Deatherage and Barrick 2014) to detect differences between the sequencing reads of each progenitor–progeny pair and annotated the different types of changes and their potential impact using SnpEff (Cingolani et al. 2012), while filtering out reads that were mapped exclusively to repeating sequences. We did not observe any biases in the composition of mutated nucleotides or amino acids for most species (supplementary figs. 4 and 5, Supplementary Material online). We noted a near ubiquitous decrease in mutation rates throughout the infection (supplementary fig. 6a, Supplementary Material online), indicating that most genomic changes occur at early stages of the infection in accordance with previous findings for PA (Yang et al. 2011; Bartell et al. 2019). These results were consistent even when excluding the large fractions of hypermutator clones found among the different strains in our database (supplementary fig. 6b and c, Supplementary Material online).

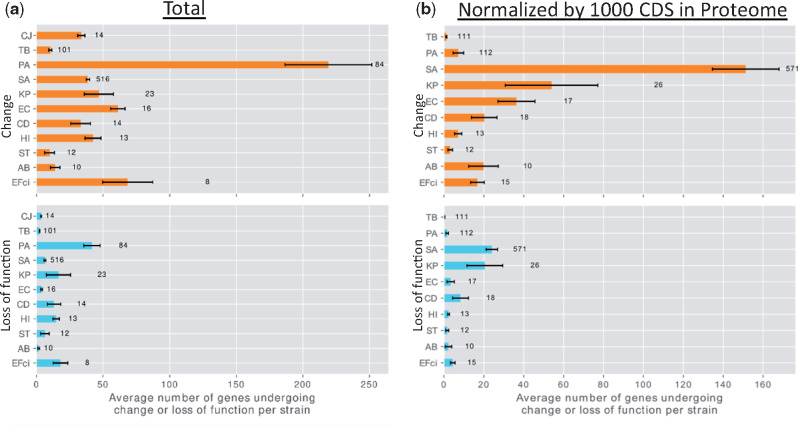

Adaptive Changes and Loss of Function of Genes Are Ubiquitous during Infections

We recorded variations likely leading to loss of function (complete deletion of a gene, loss or gain of stop codon, loss of start codon, and frameshift mutation), and variations leading to nonsynonymous genetic changes of unknown significance (e.g., amino acid substitutions), based on the annotations obtained by SnpEff (Cingolani et al. 2012). Many of the analyses described below were performed separately for two groups of genes: 1) all genes containing any genetic change (changed genes) and 2) the subgroup of genes containing variations likely leading to loss of function (genes undergoing loss of function). Changed genes, including the genes that underwent loss of function, were ubiquitous in our data and varied in their degree among strains of different species (fig. 2). The mutation burden of a strain during infection depends on its mutation rate, genome size, and the duration of the infection in generations (Drake 1991). In accordance with this, a high number of genes underwent mutations, including loss of function, in PA strains, which have large genomes (Stover et al. 2000), long durations of infection, and a high fraction of hypermutator clones (supplementary fig. 6c, Supplementary Material online). Only a small number of genes underwent genetic changes or loss of function in TB and ST strains: In the former, probably due to its extremely low mutation rate (Sherman and Gagneux 2011) and long generation time; in the latter, due to its shorter duration of infection, up to 120 days for all but one patient in our data (supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online).

Different species vary in the number of genes that underwent change or loss of function per strain. (a) Upper panel: Number of changed genes per strain in the data for each bacterial species. Lower panel: Number of genes that underwent loss of function per strain in the data for each bacterial species. Error bars represent standard error. Note that the group of genes that underwent loss of function is a subgroup of the changed genes. (b) The same, with the result for each species normalized by the number of proteins in its reference proteome, scaled to 1,000 coding sequences. Names of bacterial species are as in figure 1b. The number to the right of the bar represents the number of strains included for that bacterial species. CJ was excluded from (b) to maintain scale.

Genetic changes identified in our analysis are not necessarily the result of adaptive processes but may have occurred randomly. To pinpoint genes that were possibly affected by adaptive pressures, we searched for genes that repeatedly underwent loss of function or repeatedly underwent changes in different strains independently. We developed a statistical framework to detect those genes that underwent loss of function or any change above random expectation for each species (Materials and Methods). For a gene that underwent loss of function (any change) in k strains, we simulated the probability for genes to undergo loss of function (any change) in at least k strains by chance alone, based on the fraction of genes that underwent loss of function (any change) in each strain during the infection (supplementary fig. 7, Supplementary Material online). A gene was defined as undergoing adaptive loss of function (change) if the computed probability was below a pre-defined statistical threshold (Materials and Methods). An important distinction is that although genes undergoing loss of function are a subset of the changed genes, genes undergoing adaptive loss of function are not necessarily a subset of adaptively changed genes, as they may pass the statistical threshold only in the analysis of the subgroup of genes that underwent loss of function but not in the analysis of all changed genes.

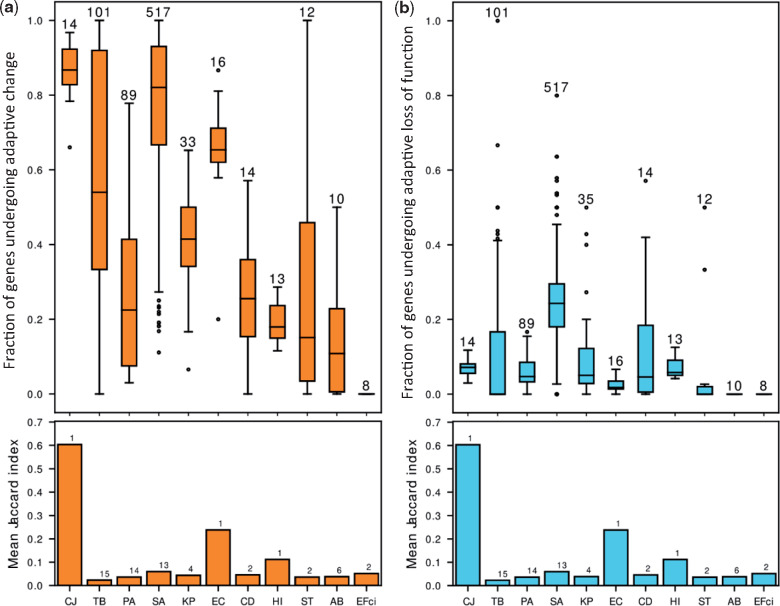

We found that genes undergoing adaptive change made up a substantial fraction of the genes with any genetic change, whereas genes undergoing adaptive loss of function made up a much smaller fraction of this subset of genes (fig. 3 and supplementary table 2, Supplementary Material online). The mean fractions of genes undergoing adaptive change and loss of function per species were correlated with the number of strains in the species in our data (Spearman correlation, r = 0.66 and r = 0.63, respectively), suggesting there may be additional genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function that we lack the statistical power to detect. CJ and EC had very high fractions of adaptively changed genes despite low numbers of strains. For these two species, all or nearly all strains originated from a single study and likely had similar genetic background and were exposed to similar selective pressures. This is reflected in high Jaccard indices between the lists of genes undergoing change in different strains (fig. 3a, Materials and Methods). This indicates that genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function in species with a small number of studies may include false positives related to the low variability between the different strains in those studies. Interestingly, the fractions of adaptively changed genes and of genes undergoing adaptive loss of function did not seem to greatly differ between opportunistic and strict pathogens or between pathogens with different routes of transmission.

The same genes of a bacterial species repeatedly undergo change or loss of function during infection by different strains. Our statistical framework defines genes that undergo change or loss of function repeatedly in a statically significant number of strains as undergoing adaptive change or loss of function, respectively. (a) Upper panel: Boxplots of the fractions of adaptively changed genes out of all changed genes in the different strains of each species. The number above the bar represents the number of strains included for that bacterial species. Lower panel: The mean similarity between the lists of genes undergoing change or loss of function in different strains of each species as measured by the Mean Jaccard Index (Materials and Methods). The number above the bar represents the number of studies included for that bacterial species. (b) Upper panel and lower panel as in (a), for genes undergoing loss of function. For most strains, there is no relationship between the fraction of genes undergoing adaptive change/loss of function and the similarity between strains of a species. Names of bacterial species are as in figure 1b.

Close inspection of the results revealed that transcription factors were prominent among genes undergoing adaptive change and among genes undergoing adaptive loss of function (supplementary table 2, Supplementary Material online), possibly indicating considerable transcriptional changes during infections. Additionally, genes related to antibiotic resistance were prominent among all adaptive lists, highlighting the selective pressures exerted by these substances. We noticed many important virulence factors that underwent loss of function among many strains, including superantigen-like proteins, fibrinogen-binding proteins, staphcoagulases, and immune evasion protein Sbi of SA. In TB, many genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function belonged to the PE/PPE families, suspected of being involved in antigenic variation.

Genes Undergoing Adaptive Change Are Generally under Positive Selection and Are Not Associated with Lower Evolutionary Conservation, Specific Genomic Regions, or Clinical Scenarios

To study the selection acting on adaptively changed genes, we compared their dN/dS ratios with the rest of the genes in the genome. We found that nonadaptively changed genes are generally under purifying selection (dN/dS < 1.0), and that dN/dS values for adaptively changed genes are statistically significantly higher by Mann–Whitney U test (one tailed, P value ≤ 0.05). Many of the adaptively changed genes are under positive selection (dN/dS > 1.0), but there is a large variance between the different genes (supplementary fig. 8, Supplementary Material online). Most interestingly, this does not hold for PA where nearly the entire proteome seems to be under positive selection.

We found that both genes undergoing adaptive change and genes undergoing adaptive loss of function were only weakly associated with low evolutionary conservation (supplementary fig. 9, Supplementary Material online), demonstrating that the changes we discovered with our statistical framework are likely derived from adaptive processes within the host environment. We detected a small number of genomic regions that were enriched with genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function (supplementary table 3, Supplementary Material online), these regions were mostly associated with operons and mobile genetic elements. Since different patients may present different clinical scenarios (carriage or infection), we assessed the results in view of this aspect. This analysis was irrelevant for most species, as nearly all patients presented a single common clinical scenario. EFci was excluded from this analysis due to lack of genes passing the statistical threshold. For SA, there were minimal differences in the genes identified in the different clinical scenarios. For KP however, we noted that there was little overlap between genes that underwent adaptive change or loss of function in the different clinical scenarios (supplementary fig. 10, Supplementary Material online). This indicates that although genes that undergo host adaptation in SA are generalizable between different clinical scenarios, for KP they are scenario specific. This finding may be related to the small number of strains in each clinical scenario for KP. Increasing the number of strains in the different scenarios will allow us to detect additional genes as adaptively changing and may increase the overlap between the different scenarios.

To reinforce the results of our automatic pipeline we verified its performance using several approaches: 1) Simulations were used to validate the performance of the statistical framework, discovering it has extremely high specificity and high sensitivity (Supplementary Material online). 2) Comparison of the pipeline results to the original studies that sequenced the genomes demonstrated that our pipeline rediscovered 72% of the genes reported to undergo mutation in the original studies (Supplementary Material online). Notably, we only had 26% overlap when comparing our list of adaptively changed genes against a previously published list for PA (Marvig, Sommer, et al. 2015). Nearly all previously designated adaptively changed genes were identified by us as accumulating genetic changes in multiple strains within our data, but many of them did not pass our statistical threshold. This indicates the stringency of our statistical framework, which may hamper the detection of some genes that are under selective pressure to undergo mutation during the infection. 3) Assuming that the genes we detect as undergoing loss of function are indeed not functional in the progeny isolates, it is unlikely that the bacteria could survive if these genes included known essential genes. Indeed, we found that 96% of the essential proteins reported in a recent proteomic study of PA (Poulsen et al. 2019) were not identified as undergoing loss of function in any of the PA strains in our data (Supplementary Material online, see also supplementary fig. 11, Supplementary Material online). 4) Finally, as our pipeline is based on the mapping of sequencing reads against a reference genome, we compared its results with results obtained by an alternative approach based on de novo assembly and annotation of the different isolates using SPAdes (Bankevich et al. 2012) and prokka (Seemann 2014) (Supplementary Material online). We found the de novo assembly-based pipeline was extremely prone to incorrectly identifying genetic changes during the infections due to assembly errors. Accordingly, a consistent small fraction of the genes undergoing change or loss of function in the de novo assembly-based pipeline were rediscovered in our reference-based pipeline (supplementary fig. 12a and b, Supplementary Material online). In contrast, the fraction of genes undergoing change or loss of function by our pipeline that were rediscovered by the de novo assembly-based pipeline was quite variable between different bacterial species and strains, ranging between 0.0 and 0.2 for changed genes in CD to 0.5–1.0 for genes undergoing loss of function in PA (supplementary fig. 12c and d, Supplementary Material online). Importantly, the main conclusions derived by applying the two pipelines are consistent (see below and in Supplementary Material online).

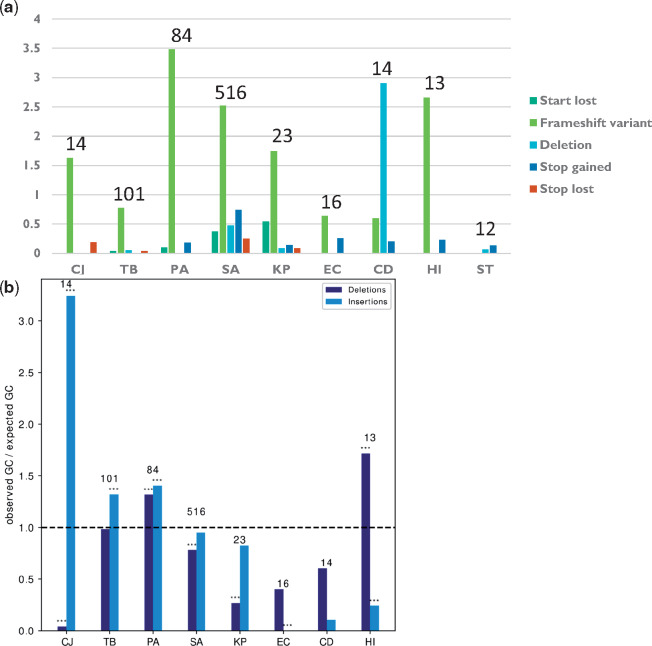

Frameshift Mechanisms with Distinct Nucleotide Biases Underlie Adaptive Loss of Function

We used the algorithm SnpEff (Cingolani et al. 2012) to predict the molecular mechanisms underlying loss of function in our data (e.g., deletion, frameshift, or nonsense mutations that lead to loss of function). Comprehensive analysis of the distributions of different mechanisms leading to loss of function of genes in different bacterial strains and species demonstrated that frameshift mutations were the most common molecular mechanism of adaptive loss of function events in all bacterial species except CD and ST (fig. 4a). Frameshift mutations require only the change of a small number of nucleotides to induce loss of function and are easily reversible (Hu and Ng 2012), making them useful tools for evolution by loss of function. We noted that frameshifts were usually minimal, with only a single nucleotide inserted or deleted, and had distinct nucleotide biases in different species, diverging from the standard %GC of the respective organism (fig. 4b). Since frameshift mutations are related to insertion and deletion events (INDELs), we compared the predicted INDELs with the results of the de novo assembly-based pipeline and found that 85.8% of predicted INDELs were reaffirmed (Materials and Methods).

Adaptive loss of function is mostly mediated by frameshift mutations. (a) The number of adaptive loss of function events due to different loss of function mechanisms, normalized by the number of progenitor–progeny pairs in each species. (b) %GC in insertions or deletions leading to frameshift events underlying adaptive loss of function, normalized by the %GC of the entire genome of each species. Asterisks denote %GC that statistically significantly differs from the %GC of the entire genome by binomial test. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, and ***P ≤ 0.001. Names of bacterial species are as in figure 1b. The numbers above the bars represent the number of strains included for that bacterial species.

Flagellar Assembly, Lipooligosaccharide Sialylation, and Pore Formation Are Adaptively Changed in Different Species

It is intriguing to find out whether orthologs in different species have been identified as undergoing adaptive change or loss of function. We predicted orthologs for all genes within all species using reciprocal BlastP (Materials and Methods) and found three pairs of orthologous genes undergoing adaptive loss of function in multiple species. In addition, two triplets and 15 pairs of orthologous genes were identified as undergoing adaptive change (supplementary table 4, Supplementary Material online). For most genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function during within-host adaptation of different species, we did not identify orthologous relationships, despite using extremely lenient thresholds for BlastP. To inspect whether these genes can be classified by similar functions or similar pathways they take part in, we assigned all genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function their respective KEGG pathways (Kanehisa and Goto 2000) and gene ontology (GO) annotations (Ashburner et al. 2000). We established an additional statistical framework to assess those pathways and functions in which genes were adaptively affected in more species than expected at random (Materials and Methods). After correction for testing of multiple hypotheses, we found that genes related to the flagellum filament, to N-acylneuraminate cytidylyltransferase activity and to pore formation were adaptively changed in more species than expected at random (supplementary table 5, Supplementary Material online). Genes related to flagellar assembly were in fact adaptively changed in all flagellated species except ST (fig. 5a) and in a remarkable 70–90% of strains. Mutations negatively affecting the function of these genes may cause the loss of the immunogenic flagella complex and a switch to nonmotile lifestyles, which has previously been demonstrated for some of the species during host infection (Marvig, Sommer, et al. 2015; Bloomfield et al. 2018; Aziz et al. 2019).

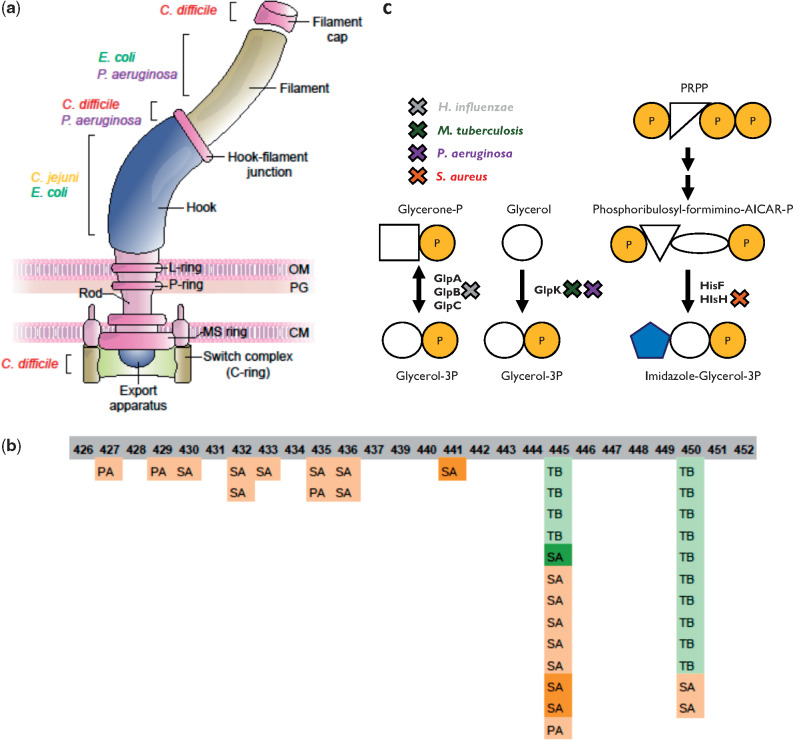

Convergent adaptation of different pathogens is evident at the pathway and functional levels (a) Flagella pathway. A schematic illustration of the bacterial flagella. Parts that include genes that underwent adaptive change or loss of function in different bacterial species are denoted. (b) Rifampicin resistance. Locations of mutations in the RRDR of RNAP in TB, PA, and SA strains are denoted. The numbers denote the corresponding residues on the RpoB of TB, which were affected by the mutations. Color indicates rifampicin treatment: dark green—confirmed treatment by rifampicin; bright green—likely treated by rifampicin based on conventional medical indications for the use of the drug; light orange—likely not treated by rifampicin based on conventional medical indications for the use of the drug; dark orange—not treated by rifampicin. (c) Glycerol-3-phosphate synthesis. Genes involved in glycerol-3-phosphate synthesis that underwent change/loss of function in a large fraction of the strains in different bacterial species. X marks the gene encoding the relevant protein that underwent adaptive change or loss of function, with the color of X indicating the species. PRPP: phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate. Names of bacterial species are as in figure 1b. Shapes represent chemical compounds: orange circle—phosphate, blank circle—glycerol, blank square—glycerone, blue pentagon—imidazole, blank triangle—ribose or ribulose, and blank ellipse—formimino group + AICAR group.

N-Acylneuraminate cytidylyltransferase activity is required in both HI and CJ for sialylation of lipooligosaccharide (LOS), a key process in the pathogenesis of both these species. Its experimental loss ex vivo has been linked to increased immunogenicity and decreased resistance to mammalian serum (Guerry et al. 2000). neuA is the only gene related to this activity, and surprisingly it was mutated in most of the HI and CJ strains, most often in particular positions. hddC, a key component in the synthesis of an additional capsular polysaccharide, was also mutated in all CJ strains. This reaffirms and generalizes the results of Pettigrew et al. (2018), who noted sialyltransferase mutations in HI during infection of patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Genes related to pore formation underwent adaptive loss of function in most Gram-negative bacteria in our data, for which it is known that small hydrophilic drugs, such as β-lactams, use the pore-forming porins to gain access to the cell interior (Ghai I and Ghai S 2018). This generalizes results by previous studies, included in our data, which identified mutations in specific genes related to pore formation occurring during host adaptation in specific bacterial species (Porse et al. 2017; Sherrard et al. 2017; Gaibani et al. 2018; Pettigrew et al. 2018). The consistent mutations in these genes across many species may be related to decreased susceptibility to these antibiotics.

Further Convergent Changes in KEGG Pathways Are Evident in Genes Undergoing Nonadaptive Changes or Loss of Function

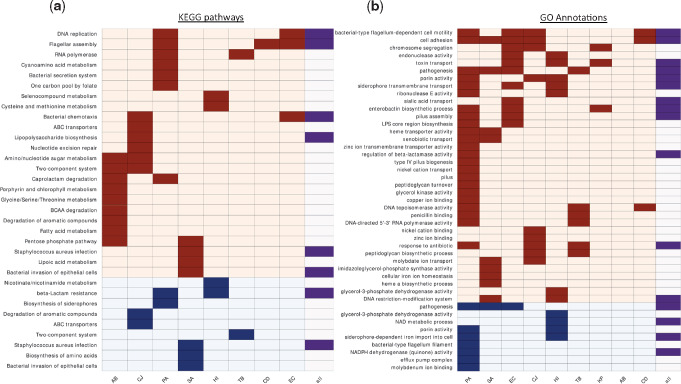

The previous analyses were restricted to genes that we determined as undergoing adaptive change or loss of function in the various species. In the next analysis, we assigned KEGG pathways to all genes that underwent change or loss of function in our data to assess whether we can detect convergent adaptation at the pathway level. We developed a statistical framework to assess which pathways were affected more than expected at random in the strains of each bacterial species and in all strains across all species jointly (Materials and Methods). This analysis was carried out to detect statistically significantly overrepresented pathways among genes undergoing change and among genes undergoing loss of function. Most overrepresented pathways were unique to single species, but some pathways stood out in multiple species (fig. 6a and supplementary table 6, Supplementary Material online). No pathway was overrepresented among genes undergoing change or loss of function at the whole-data set level alone. Most prominently, the Flagellar assembly and Bacterial chemotaxis pathways were overrepresented among changed genes in the same species as in the previous analysis, supporting a possible shift to nonmotility during infection. Pathways related to amino acid synthesis and metabolism were overrepresented among genes undergoing change and among genes undergoing loss of function in multiple species, a finding which could be related to adaptation to the amino acid-rich host environment.

Selected KEGG pathways and GO annotations that were overrepresented among genes undergoing change or loss of function in different bacterial species. (a) Each row represents a different pathway: Rows with light orange background—overrepresented pathways among changed genes; rows with light blue background—overrepresented pathways among genes undergoing loss of function. Dark boxes indicate that the pathway was overrepresented in the species appearing on the column. The rightmost column indicates whether the pathway was overrepresented when considering all strains of all species together. (b) As in (a) for GO annotations. Names of bacterial species are as in figure 1b.

Some of the other pathways that were overrepresented in multiple species are likely related to antibiotic pressures (fig. 6a and supplementary table 6, Supplementary Material online). For example, Beta-lactam resistance and Two-component system, which are related to β-lactam antibiotics and colistin, respectively, with resistance to the latter emerging in AB via the PmrAB two-component system. Another remarkable example is the RNA polymerase (RNAP) complex. We detected adaptive changes in RNAP in both TB and PA strains (fig. 6a), as well as in the β-subunit of SA (supplementary table 2, Supplementary Material online). Close inspection of these mutations revealed many missense mutations within the rifampicin-resistance determining region (RRDR, supplementary fig. 13, Supplementary Material online) (Telenti et al. 1993; Andre et al. 2017), which has also been linked to decreased sensitivity to other antibiotics (Guérillot et al. 2018). Indeed, most PA and SA-infected patients with RRDR mutations in our data have no evidence of rifampicin exposure (fig. 5b), raising the possibility that these mutations might be selected due to treatment by other drugs. For in-depth analysis of RNAP mutations, see Supplementary Material online.

Common Changes in the Uptake of Iron and Other Metals

We performed a similar analysis to assess which GO annotations were statistically significantly overrepresented within the gene groups that underwent change or loss of function in the strains of each species and in all strains across all species jointly (fig. 6b and supplementary table 7, Supplementary Material online). We identified various GO annotations as overrepresented among genes undergoing change and among genes undergoing loss of function in multiple species, including GO annotations related to cell surface structures, such as flagella, pili, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), and peptidoglycans, alongside several GO annotations related to iron metabolism. Genes related to uptake or synthesis of siderophores were changed or underwent loss of function in most Gram-negative species, suggesting a possible shift from siderophore-based to heme-based iron scavenging or the development of cheating behavior, as has been shown for PA (Marvig et al. 2014; Andersen et al. 2015). Surprisingly, we found that the phuR, hasR, and isdB heme uptake systems were also mutated in some PA and SA strains. Since phu operon mutations in PA have been shown to lead to increased expression of the phu heme uptake system during chronic infections (Marvig et al. 2014), it is possible that these mutations do not impair heme uptake. Nevertheless, the phu system has been shown to be detrimental in high heme concentrations, so mutations impairing heme uptake may also confer an advantage in the host environment (Andersen et al. 2018). Heme biosynthesis was additionally overrepresented among changed genes in SA, supporting the exogenous uptake of this product. This result is also in line with overrepresentation among changed genes of the KEGG pathway Porphyrin and chlorophyll metabolism in AB (fig. 6a). Although iron metabolism was the most prominent, GO annotations related to the metabolism and uptake of other trace elements were also overrepresented among changed genes during the infection of multiple pathogens, including molybdenum, zinc, nickel, and copper, a finding which may suggest that modulation of metal scavenging may be a general adaptive mechanism during infections.

Many GO annotations were again linked to antibiotic resistance. Among those stood out the changes in glycerol-3-phosphate metabolism. A recent paper by Bellerose et al. (2019) revealed that changes in the TB glycerol kinase glpK reduce sensitivity to multiple antibiotics. In our data, we detected not only glpK as adaptively changed in TB but also several GO annotations related to glycerol-3-phosphate metabolism in three additional species. These results could indicate that changes in glycerol-phosphate metabolism may lead to reduced sensitivity to antibiotics in additional species, a possible global mechanism for reduced antibiotic sensitivity. Furthermore, all processes have similar products, possibly implicating the decrease in glycerol-3-phosphate itself as the adaptive process, as hypothesized by Bellerose et al. for TB (Bellerose et al. 2019) (fig. 5c). Mutations in the TB glpK during host adaptation were also noted by Trauner et al. (2017).

As noted above, many genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function encode known virulence factors. Our analysis of GO annotations further supported this conclusion, with multiple annotations related to bacterial virulence overrepresented among genes undergoing change and among genes undergoing loss of function (fig. 6b). This may indicate decreased virulence during chronic infections or a shift from acute virulence to chronic virulence, as has been previously suggested for PA (Hauser et al. 2011; Winstanley et al. 2016). SA and Burkholderia pseudomallei have also been suggested to attenuate their virulence during certain chronic infections (Viberg et al. 2017; Suligoy et al. 2018).

To assess our conclusions, we applied our statistical framework to genes identified by the de novo assembly-based pipeline as undergoing change or loss of function, in order to identify among them genes that were adaptively changed or adaptively underwent loss of function. We found that many of our conclusions stay firm for this set of genes (Supplementary Material online).

Discussion

In this work, we took a global approach to study within-host adaptation of bacterial pathogens. We investigated 11 different taxa of bacterial pathogens, representing much of the variety of bacterial pathogens causing chronic disease in humans. We showed that these pathogens undergo genetic changes during infections, including loss of function mutations. Many identical changes were discovered independently in different strains belonging to the same bacterial species, infecting different patients, indicating adaptive evolution.

Although we found little orthologous relationship between genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function in different species, analysis of meta-categories including KEGG pathways and GO annotations demonstrated that genes passing the statistical threshold for determining adaptive change or loss of function in different pathogens were often related to similar pathways, structures, and biological functions. Furthermore, when broadening the scope of our analysis beyond genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function to genes which did not pass the statistical threshold, we unveiled pathways and functions that were consistently affected in many strains of unrelated species via different genes. This demonstrates remarkable convergent evolution between different pathogens during host infection, despite distinct lifestyles and pressures.

Previous studies examined adaptation in the context of a single species and a single clinical presentation. In this study, we included data of multiple bacterial species, from different tissues, causing different clinical presentations, treated with different antimicrobial drugs, originating from different geographical regions and studied by variable laboratory techniques. DNA was extracted from single colonies, from multiple colonies or even directly from patient samples in the different studies. Additionally, the different studies employed different sequencing machines and approaches (long-read sequencing, single-end sequencing, paired-end sequencing, etc.). The joint analysis of these different data limits our ability to detect specific signals that may relate to specific clinical presentations associated with different symptoms or treatments. Rather, our approach allows us to detect global convergent adaptation, which is not limited to a specific scenario. Indeed, we detected substantial convergence despite these differences by using large numbers of patients and stringent statistical frameworks. Expansion of our framework with additional data could allow the detection of further convergent adaptive trends and overcoming nongeneralizable results for species with strains originating from a single study. Also, although we focused on protein-coding genes appearing in reference proteomes, applying similar methodologies to additional genomic elements/regions could lead to additional insights regarding within-host evolution (Khademi et al. 2019). It should be also possible to study subgroups of patients from our database to focus on specific treatments or clinical presentations associated with specific sets of symptoms.

Adaptive changes occurring in multiple species were frequently associated with common antigens recognized by the human immune apparatus, including flagellar filament, substrate of TLR5; LOS/LPS, substrates of TLR4; peptidoglycans, substrates of TLR2; iron acquisition systems, considered highly immunogenic (Wandersman and Delepelaire 2004). Many adaptive changes also relate to antibiotic persistence/resistance, especially evident in RNAP. Rifampicin is an antimicrobial agent acting by the inhibition of RNAP. Bacterial resistance to rifampicin is common and usually arises by mutations in the residues of the rifampicin binding site of RNAP (Campbell et al. 2001). The region where the mutations most commonly arise has been termed the RRDR (Telenti et al. 1993). We showed that RNAP accumulates mutations in PA, SA, and TB during infections, frequently located in the RRDR (supplementary fig. 13, Supplementary Material online). These mutations appear in many strains with no evidence of exposure to rifampicin, although we cannot rule out exposure to rifampicin administered for concurrent infections by other pathogens. Strong selective forces acting on genes linked to antibiotic resistance had clear mutational patterns, with mutations at the same positions recurring independently in different strains (fig. 5b). Similar patterns identified in genes that are not currently linked with antibiotic persistence/resistance, may hint at their involvement in these processes (Supplementary Material online). This is supported by our independent detection of glpK frameshift mutations, which were recently linked to antibiotic resistance in TB (Bellerose et al. 2019) (fig. 5c). We suggest that similar mechanisms may be involved in antibiotic resistance in additional bacterial species. It is not surprising that the innate immune system and antibiotic treatment seem to be major drivers of convergent within-host adaptation in different species, as both exert powerful general selective pressures on bacterial pathogens that are usually not confined to specific species.

The adaptive mutations we detect arise repeatedly in independent infections, indicating that they may confer advantages within the host environment. It is fascinating to ponder why these mutations arise repeatedly in organisms that undergo patient-to-patient transmission rather than remain fixed across the species. Bacteria encounter stringent bottlenecks when infecting new patients (Moxon and Kussell 2017). We hypothesize that adaptive changes become disadvantageous in the context of these bottlenecks and are therefore subject to repeated cycles of negative and positive selection. The mutations might persist within small subpopulations or independently arise within each infective cycle as bacteria re-encounter their chronic niches. This theory is supported by genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function that are of vital importance for acute virulence, including the ESX-1 secretion system of TB (Gröschel et al. 2016) as well as the flagella in CJ (Black et al. 1988).

Changes in virulence factors during infection have also been hypothesized to relate to virulence attenuation during chronic infections and to a shift from acute virulence to chronic virulence (Hauser et al. 2011; Winstanley et al. 2016). We believe these interpretations are not mutually exclusive, as bacteria employing acute infection strategies can be extremely virulent, leading to death within hours or days. The loss of factors required for acute virulence disarms the pathogen of these deadly weapons and underlies a shift toward lesser virulence (Furukawa et al. 2006). Indeed, pathogens isolated from established chronic infections are less cytotoxic than earlier isolates from the same patients (Gellatly and Hancock 2013). Therefore, the change or loss of function of acute virulence factors may underlie both an attenuation of virulence and a shift toward chronic virulence.

Finally, we believe our results to be an important resource for screening candidate antivirulence targets. Antivirulence therapy is an emerging strategy of antimicrobial treatment employing agents targeting virulence factors to reduce the virulence of infecting pathogens rather than eliminating them, thus avoiding the exertion of selective pressures for resistance. A major limitation of this paradigm is that targeting virulence factors, which are beneficial in vivo, leads to reduced fitness of the pathogen and creates evolutionary constraints inducing resistance (Allen et al. 2014). Our results offer a rich resource of antivirulence targets that are nonbeneficial in vivo and could therefore prove to be effective targets for disarming infecting bacteria. Conversely, targeting virulence factors that frequently accumulate genetic changes during infections may lead to development of antibiotic resistance, as evolution of those genes is possibly less constrained within the host environment (Rezzoagli et al. 2018). The rich resource of data that we provide establishes the foundation to further study the basic principles of within-host adaptation and their exploitation in antibacterial therapy.

Materials and Methods

Data Organization

Compiling the Database

Whole-genome sequencing data of bacterial pathogens during infection were curated by searching NCBI’s databases for relevant studies using several search terms, such as “within-host adaptation,” “intrahost evolution,” “infectious episode AND WGS,” “longitudinal AND sequencing,” “microevolution,” “serial isolates,” and “genomic adaptation.” Relevant studies were defined as ones including whole-genome sequencing data of bacterial isolates sampled in at least two time points during a single infection of at least a single human host with a single bacterial pathogen (table 1, coinfections with other pathogens during the time period were allowed). NCBI Assembly accession numbers were collected when available, and otherwise NCBI SRA Run accession numbers were used. The database can be found in supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online.

Most of the studies in our database included a single sequenced colony for each sample, and a single sample for each time point, with a subset of the studies including multiple colonies or samples for each time point. Another subset of the studies included data directly sequenced from patient samples, without the isolation of a clone beforehand. For simplicity, we refer to the sequencing results of a single colony as an isolate throughout the paper.

Downloading and Processing the Data

Data were downloaded using the SRA Toolkit (Leinonen et al. 2011) and assembled using the SPAdes Assembler v.3.10.1 (Bankevich et al. 2012). When assemblies were already available, they were directly downloaded. Reference or representative genomes were determined using NCBI’s E-Direct command line utilities v.5.80 (Kans 2019). When several reference genomes were available, the closest one to the assemblies was determined by a custom script exploiting QUAST v.4.5 (Gurevich et al. 2013) and Mash v.2.1 (Ondov et al. 2016). We chose the reference genomes where the highest fraction of the genome was aligned to contigs of the different assemblies and the average Mash distance to the assemblies was the smallest. Notably, for most species only a single reference genome was available, and for E. coli and for A. baumannii one reference genome was found to be the closest to all strains. Furthermore, for each strain the difference between the Mash distances of any two assemblies to the reference genome, was nearly always 0.0.

Determining the Phylogenetic Relationship between Isolates

We developed the TRACE algorithm to determine the phylogenetic relationship between the isolates from each patient as follows (fig. 1c):

Isolates from each patient are divided to clones based on phylogenetic trees: kSNP v.3.1 (Gardner and Hall 2013; Gardner et al. 2015) is used to construct core single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) matrices based on the assemblies of the isolates of each patient and up to 100 complete genomes for the relevant bacterial species from NCBI’s Assembly database. PAUP v.4.0 (Swofford 2003) is then used to construct maximum likelihood trees out of the matrices, picking each consensus tree out of 1,000 bootstrapped samples. Finally, we inspect the location of the isolates on the constructed tree, and consider isolates found on a single clade to originate from the same clone. For additional validation, the MLST profile (Maiden et al. 1998) for each isolate is also predicted using mlst v.2.16 (Jolley and Maiden 2010; Seeman 2017) and isolates within the same clone, which differ in their profiles, are split to separate clones (Supplementary Material online).

In order to determine which isolates may share a direct progenitor–progeny phylogenetic link, TRACE then constructs the phylogenetic relationships between the isolates of each clone. kSNP v.3.1 (Gardner and Hall 2013; Gardner et al. 2015) and breseq v.0.32 (Barrick et al. 2014; Deatherage and Barrick 2014) are utilized to construct SNP matrices between the isolates and custom scripts are used to assess the least parsimonious path possible between the isolates in which each isolate is derived from an earlier time point isolate. In cases where two isolates of the same time point are available, an artificial common ancestor is constructed as the intersection of the SNP profiles of the two isolates, and trees including this isolate are additionally inspected. Clones with three or more isolates sampled at the same time point were excluded. Finally, TRACE defines pairs of progenitor and progeny isolates in each tree and assigns each pair a confidence level based on its frequency among the 1% highest scoring trees for that clone. We assessed the performance of the TRACE pipeline using both simulated and empirical data, verifying its high accuracy under a broad range of parameters (Supplementary Material online).

Analysis of Genetic Changes

Determining the Variation between Isolates

Breseq v.0.32 (Barrick et al. 2014; Deatherage and Barrick 2014) was used to call genetic and genomic differences between each isolate and the respective reference genome of the species by mapping the sequencing reads to the reference genome and identifying discrepancies between the aligned reads and the reference genome sequence. Sequence repeats were detected using Vmatch package (http://www.vmatch.de, last accessed November 16, 2020) and excluded from all analyses. The differences between the isolate and the reference genome were then compared within each progenitor–progeny pair using the COMPARE function of gdtools (Deatherage and Barrick 2014) to determine genetic and genomic variations within the pair.

Defining Changed Genes and Genes Undergoing Loss of Function

We used SnpEff v.4.1 (Cingolani et al. 2012) to classify the impact of the above differences as low (e.g., synonymous substitutions), moderate (e.g., nonsynonymous substitutions), high (e.g., frameshift mutations), or modifier (e.g., mutations upstream to the coding sequence [CDS]). A gene with variations of moderate effect that were found in the progeny strain and not the progenitor strain was determined as changed within the progenitor–progeny pair. A gene with high-impact variations that were found in the progeny strain and not the progenitor strain was determined both as undergoing change and as undergoing loss of function within the progenitor–progeny pair. Genes with high-impact mutations in the progenitor strain were excluded as we considered them as putative pseudogenes.

A gene that underwent change or loss of function in at least one of progenitor–progeny isolate pairs of a strain was determined as a gene that underwent change or loss of function, respectively, in that strain. Additionally, each gene was assigned a score between 0.0 and 1.0 that reflects its loss of function across all progenitor–progeny isolate pairs of the strain. A similar score was determined for changed genes. The score is defined as the fraction of progenitor–progeny pairs in which the gene was affected out of all possible pairs. Possible pairs are defined as all pairs except the ones where the progenitor isolate is downstream in the tree (based on the results of TRACE) to a progenitor–progeny pair in which the gene was affected. For example, in case of two progenitor–progeny pairs a -> b and b -> c, and a gene undergoing loss of function between a and b, the pair b -> c should not be regarded as a possible pair for loss of function of this gene because the gene underwent loss of function upstream in the tree. Note that change or loss of function events that are predicted by TRACE to occur between a progenitor isolate and a common theoretical ancestor of two progeny isolates sampled at the same time point, are counted only once despite appearing in two progenitor–progeny pairs.

Statistical Framework to Assess Adaptive Change and Loss of Function

After assigning scores per strain to genes that underwent loss of function, we assigned gene scores at the species level. Each gene g in the reference genome of each species was assigned a score, Lg, which is the sum of its per-strain scores across all strains in which it underwent loss of function. This score reflects the number of strains in which the gene underwent loss of function, while taking into account the fraction of progenitor–progeny pairs in which these events occurred per strain. In further computations, we take the floor function of Lg, which is the greatest integer less than or equal to Lg (⌊Lg⌋), as the number of strains in which the gene underwent loss of function.

To evaluate if the repeated loss of function of a gene in several strains was statistically significant, we determined whether ⌊Lg⌋ is greater than expected at random by random simulations. To create the random simulations, we first assigned each strain i a probability of loss Pi:

Note that here also we do not simply count the number of genes that underwent loss of function in the strain, but take into account the fractions of progenitor–progeny pairs in which they underwent loss of function (their scores per strain). We then simulated loss of function in 106 genes, determining for each gene at random whether it did or did not undergo loss of function. The probability for each simulated gene to undergo loss of function in each strain is equal to the strain’s loss probability, Pi. We counted the number of strains in which each gene underwent loss of function in the simulations and described the distribution of the number of genes that underwent loss of function in each number of strains (supplementary fig. 7, Supplementary Material online). Finally, based on this distribution, we treated the fraction of genes that underwent loss of function in at least ⌊Lg⌋ strains based on the simulations as the P value for a gene g whose total score across all strains for loss of function was ⌊Lg⌋. Genes with adjusted P value ≤ 0.1 after correcting for testing of multiple hypotheses by the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) were determined to undergo loss of function above random expectation and their loss of function was therefore considered as putatively adaptive. We conducted a similar statistical test for changed genes to detect adaptively changed genes, replacing Lg with Cg, a similar score for each gene that was determined as changed.

Computation of Mutation Rates

Mutation rates were calculated for strains with isolates sampled at three or more time points. For each isolate, we extracted the time point in which it was isolated and counted the number of SNPs that do not appear in isolates sampled at the very first time point for the strain. We then fitted a second-degree polynomial for each strain based on the time points and numbers of SNPs of the different isolates and extracted its first derivative (mutation rate) and second derivative (rate of change for the mutation rate).

Calculating dN/dS Ratios

dN/dS ratios were calculated using the raw counts of nonsynonymous/synonymous mutations across all progenitor–progeny pairs of each strain.

Determining Hypermutator Clones

We defined hypermutator clones as clones with at least one isolate with a complete deletion or loss of function mutation in one of the genes of the DNA mismatch repair system, where mutations have been shown to confer a strong or a very strong hypermutator effect in E. coli. We also included isolates with mutations in one of the genes of the GO system, where mutations have been shown to confer a weak to strong hypermutator effect in E. coli (Oliver and Mena 2010). For M. tuberculosis, we also included mutations in the nucS gene, which is required for mismatch repair in this organism (Castañeda-García et al. 2017). Orthologs in the different species were determined using BlastP v.2.4.0+.

Determining the Similarity in the Lists of Genes Undergoing Change or Loss of Function between the Different Isolates

To determine the similarity between different strains of each species, we compared their lists of changed genes. We computed the Jaccard index between the changed gene lists of each two strains in each species and finally calculated the mean of this measure across all strain pairs. A similar calculation was performed for the lists of genes that underwent loss of function.

Characterizing the Genomic Variations

Assessing Mechanisms of Adaptive Loss of Function

We calculated the relative frequency of different mechanisms underlying adaptive loss of function in the different species as determined by SnpEff v.4.1 (Cingolani et al. 2012). The number of events of genes undergoing adaptive loss of function caused by each mechanism was normalized by the number of progenitor–progeny pairs in the respective species.

Examining %GC in Frameshift Mutations

In order to characterize the nucleotides that were inserted or deleted in frameshift mutations, we compared the number of observed inserted/deleted G/C bases with the expected value based on the %GC of the entire genome by a binomial test.

Confirming INDELs by the De Novo Assembly-Based Pipeline

Frameshift mutations during the infection are caused by INDELs in the CDS of the gene. Since we found that frameshifts constitute the major mechanism underlying loss of function during the infection, we validated INDEL mutations predicted by our pipeline using the de novo assembly-based pipeline (Supplementary Material online). To test the presence of INDELs in the de novo assembly-based pipeline, we extracted the gene in which each INDEL was found and searched for CDS with the same annotation in the progenitor and progeny isolates for the respective pair in which the INDEL was determined. We chose cases where only a single CDS in both the progenitor and progeny isolates had the same annotation as the gene hosting the INDEL. We searched for matches between the progenitor and progeny sequences, where five nucleotides before and after the site of the predicted INDEL remained identical, and the INDEL site itself underwent the expected insertion or deletion. The result may be an underestimation due to SNPs or other variations in the preceding or succeeding nucleotides.

Detecting Genomic Regions That Are Enriched with Genes Undergoing Adaptive Change or Loss of Function

We performed hypergeometric tests for genomic regions of size 10,000 base pairs to detect regions that are enriched with genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function in their respective genomes by considering the number of genes in the region, the number of genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function, and the respective numbers for the entire genome. Regions with adjusted P value ≤ 0.1 after correction for testing of multiple hypotheses using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) were considered statistically significantly enriched with genes that underwent adaptive change or loss of function.

Calling Orthologs Undergoing Adaptive Change or Loss of Function

Determination of orthologs between different species was based on reciprocal BLAST, defining orthologs as the best BLAST hits with an extremely lenient E-value cutoff of 100.0, with the aligned region covering at least 30% of the query and the BLAST score being at least 10% of the BLAST score of a perfect match for the query.

Analysis of Pathways and Functions Affected by the Mutations

We analyzed common pathways and functions affected by mutations in different species by two analyses, the first focused on genes undergoing adaptive change or loss of function and the second included all genes undergoing change or loss of function. For these analyses, we assigned each gene the pathways to which it belongs using KEGG (Kanehisa and Goto 2000) and its GO annotations using QuickGO (Ashburner et al. 2000; Binns et al. 2009; Gene Ontology Consortium 2019).

Assessing KEGG Pathways and GO Annotations for Genes That Underwent Adaptive Change or Loss of Function

To assess whether genes related to similar pathways or functions underwent adaptive change or loss of function in different species, we counted in how many species each pathway or annotation included genes that underwent adaptive change or loss of function. As a control, we performed 100,000 simulations, where in each simulation we chose random genes as undergoing adaptive loss of function (change) in each species according to the actual number of genes that underwent adaptive loss of function (change) in that species, respectively. The P value for each pathway or annotation was the fraction of simulations where genes of the pathway underwent adaptive loss of function (change) in at least as many species as in the actual results. Finally, we corrected the P values for testing of multiple hypotheses using the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). The use of simulations controls for differences in the number of genes in different pathways.

Assessing KEGG Pathways and GO Annotations That Are Overrepresented among Genes Undergoing Change or Loss of Function

It is possible that there are genes in various strains that underwent change or loss of function that were not determined as adaptive but are still involved in common pathways. To this end, we assessed the enrichment of specific KEGG pathways or GO annotations in the data of all genes undergoing change or loss of function in a strain by simulations. As a basis for the simulations, we used the number of genes Ni undergoing loss of function (change) in each strain i. We carried out 100,000 simulations of all our strains. In each simulation, we randomly chose Ni genes to undergo loss of function (change) in each strain i and counted in how many strains each KEGG pathway or GO annotation was affected. The P value for each pathway or annotation was the fraction of simulations where it underwent loss of function (change) in at least as many strains as in the actual results. Finally, we considered all pathways with adjusted P value ≤ 0.1 after correcting for testing of multiple hypotheses by the Benjamini–Hochberg method (Benjamini and Hochberg 1995) to be overrepresented among genes undergoing loss of function (change). This process was carried out for the strains of each bacterial species and for all the strains across all species jointly. We carried out a similar analysis for GO annotations.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Y. Altuvia and I. Rosenshine for fruitful discussions and invaluable advice. We thank M. Barsheshet and A. Bar for their support and comments and R. Hershberg, E. Bolotin, T. Pupko, U. Gophna, A. Stern, and R. Pascale for their helpful advice and assistance. We thank Y. Yadegari for the illustration in figure 5a. This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation, administered by the Israeli Academy for Sciences and Humanities (grant 876/17). Y.E.G. is partially supported by fellowships of the Hoffman Program, the Foulkes Foundation, and the Data Sciences program of the Planning and Budgeting Committee of the Israel Council for Higher Education.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed extensively to the work presented in this paper. H.M. and Y.E.G. conceived the study; Y.E.G. compiled the database, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; H.M. supervised the work and wrote the manuscript.

Data Availability

Accession numbers for all relevant sequencing data are listed in supplementary table 1, Supplementary Material online. The scripts used for the downloading of the data, the processing of the data, the assessment of within-host variations, the TRACE pipeline, and the statistical framework are available through the following github repository: https://github.com/YairGatt/WithinHostAdaptation (last accessed November 16, 2020).

Common Adaptive Strategies Underlie Within-Host Evolution of Bacterial Pathogens

Common Adaptive Strategies Underlie Within-Host Evolution of Bacterial Pathogens