- Altmetric

Membrane transporters mediate cellular uptake of nutrients, signaling molecules, and drugs. Their overall mechanisms are often well understood, but the structural features setting their rates are mostly unknown. Earlier single‐molecule fluorescence imaging of the archaeal model glutamate transporter homologue GltPh from Pyrococcus horikoshii suggested that the slow conformational transition from the outward‐ to the inward‐facing state, when the bound substrate is translocated from the extracellular to the cytoplasmic side of the membrane, is rate limiting to transport. Here, we provide insight into the structure of the high‐energy transition state of GltPh that limits the rate of the substrate translocation process. Using bioinformatics, we identified GltPh gain‐of‐function mutations in the flexible helical hairpin domain HP2 and applied linear free energy relationship analysis to infer that the transition state structurally resembles the inward‐facing conformation. Based on these analyses, we propose an approach to search for allosteric modulators for transporters.

Kinetic and mutational studies show that reaching the inward‐facing configuration is rate‐limiting during the archaeal aspartic acid transport cycle.

Introduction

The fluxes of small molecules across biological membranes mediated by membrane‐embedded transporters are essential to life, and their dysregulation leads to numerous diseases (Cesar‐Razquin, Snijder et al, 2015). High‐resolution structures of transporters have revealed conformations that expose substrate‐binding sites to the opposite sides of the membrane, providing a structural rationale for the alternating access mechanism (Drew & Boudker, 2016). In contrast, we know relatively little about the structures of high‐energy transition states (TSs) that are essential to understand the kinetic mechanisms, how the kinetics are affected by post‐translational modifications, or small‐molecule modulators (Kortagere, Fontana et al, 2013; Li, Hasenhuetl et al, 2015; Czuba, Hillgren et al, 2018) or how to develop drugs that modulate transporter activities (Rives, Javitch et al, 2017). While many computational approaches are used to map the energy landscapes of the transporters (Weng, Fan et al, 2010; Espinoza‐Fonseca & Thomas, 2011; Jiang, Shrivastava et al, 2011; Stolzenberg, Khelashvili et al, 2012; Weng, Fan et al, 2012; Gur, Zomot et al, 2013; Stelzl, Fowler et al, 2014; Gur, Zomot et al, 2015; Moradi, Enkavi et al, 2015; Liao, Marinelli et al, 2016; Cheng, Kaya et al, 2018; Selvam, Mittal et al, 2018; Wang, Albers et al, 2018), experimental data reporting on TSs are scarce (Leninger, Sae Her et al, 2019; Wu, Wynne et al, 2019).

TSs are only transiently populated and cannot be studied by direct structural methods. However, linear free energy relationship (LFER) analyses provided insights into the TSs of enzyme reactions (Fersht & Wells, 1991; Hollfelder & Herschlag, 1995; Mihai, Kravchuk et al, 2003), protein folding (Matouschek, Kellis et al, 1989; Curnow & Booth, 2009; Huysmans, Baldwin et al, 2010; Schlebach, Woodall et al, 2014; Paslawski, Lillelund et al, 2015), and channel opening (Grosman, Zhou et al, 2000; Auerbach, 2003; Sorum, Czege et al, 2015). LFERs correlate the effects of amino acid substitutions and ligands on the reaction rates to the changes in the equilibrium constant for an observed transition. From these correlations, one can infer whether the perturbed region of the protein resembles the initial or the final conformation in the TS (Evans & Polanyi, 1936; Leffler, 1953; Fersht & Sato, 2004). Here, we use LFERs to characterize the structure of the TS during substrate translocation by GltPh, an aspartate/sodium symporter from the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium Pyrococcus horikoshii.

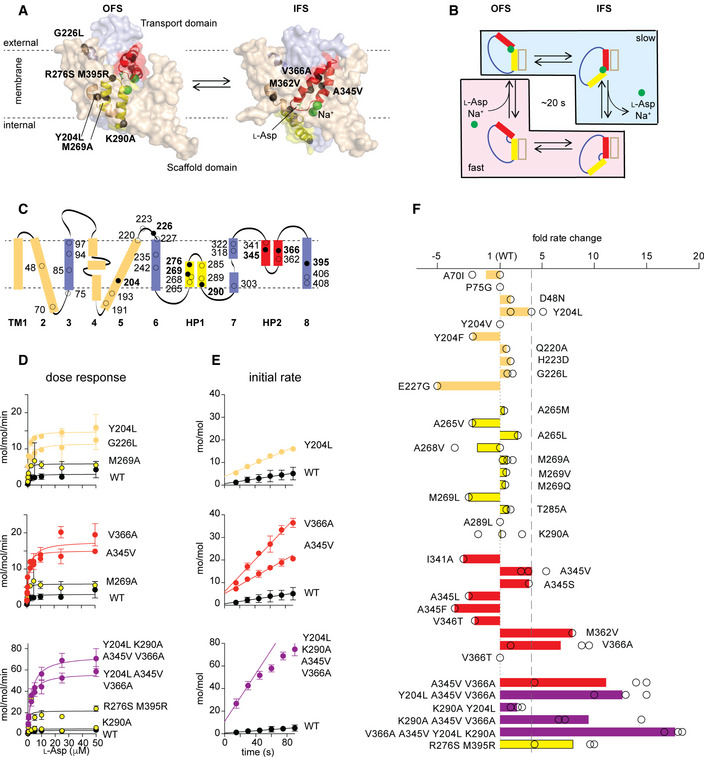

GltPh is an extensively studied homologue of human excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) (Vandenberg & Ryan, 2013). It utilizes the physiological transmembrane sodium (Na+) gradient by symporting one aspartate (l‐Asp) and three Na+ ions (Boudker, Ryan et al, 2007; Ryan, Compton et al, 2009; Groeneveld & Slotboom, 2010). The mechanism of GltPh is well understood from a structural perspective. GltPh is a homotrimer, with each protomer consisting of a trimerization scaffold domain and a transport domain, containing the l‐Asp‐ and Na+‐binding sites. A ~15 Å “elevator” movement of the transport domain along the membrane normal from an outward‐facing state (OFS) to an inward‐facing state (IFS) delivers solutes across the bilayer (Fig 1A) (Yernool, Boudker et al, 2004; Akyuz, Altman et al, 2013; Erkens, Hanelt et al, 2013; Georgieva, Borbat et al, 2013; Hanelt, Wunnicke et al, 2013; Akyuz, Georgieva et al, 2015; Hanelt, Jensen et al, 2015; Guskov, Jensen et al, 2016; Canul‐Tec, Assal et al, 2017; Ruan, Miyagi et al, 2017; Arkhipova, Trinco et al, 2019). During this transition, the transport domain forms two alternative interfaces with the scaffold involving pseudosymmetric helical hairpins 1 and 2 (HP1 and HP2) (Yernool et al, 2004; Crisman, Qu et al, 2009; Reyes, Ginter et al, 2009). HP1 is sandwiched between the transport and scaffold domains, and HP2 lines the extracellular surface of the protomer in the OFS. In contrast, HP2 is positioned on the interface, and HP1 faces the cytosol in the IFS (Fig 1A). HP2 forms a lid over the substrate‐binding site and serves as the extracellular gate (Boudker et al, 2007; Huang & Tajkhorshid, 2008; Shrivastava, Jiang et al, 2008; Grazioso, Limongelli et al, 2012; Heinzelmann, Bastug et al, 2013; Zomot & Bahar, 2013; Verdon, Oh et al, 2014). Following the release of l‐Asp and Na+ ions in the IFS via an incompletely understood mechanism, HP2 collapses onto the substrate‐binding site (Oh & Boudker, 2018; Garaeva, Guskov et al, 2019). The return of the transport domain to the OFS completes the cycle (Fig 1B). Time‐resolved single‐molecule Forster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) recordings established the key features of the elevator movements of the transport domains (Akyuz et al, 2013; Erkens et al, 2013; Akyuz et al, 2015). These studies suggested that the translocation of the substrate‐loaded transport domain from the OFS to the IFS is the rate limiting step of the cycle, but the nature of the high‐energy rate‐determining barrier remained unknown.

Gain‐of‐function GltPh variants

AA GltPh protomer in the OFS and IFS is shown in semitransparent surface representation with the scaffold and transport domains colored wheat and blue, respectively. HP1 (yellow) and HP2 (red) are emphasized as cartoons. Bound l‐Asp and Na+ ions are shown as green sticks and spheres, respectively. Select amino acids mutated in this study are shown as black spheres.

BSchematic representation of the GltPh transport cycle showing one protomer. Comparatively rapid and slow steps of the cycle are shaded pink and blue, respectively.

CThe topology of a GltPh protomer showing tested mutation sites (circles) with filled circles corresponding to those shown in (A).

D, ERepresentative examples of dose–response curves and time courses. Lines through the dose–response curves are fits to the Michaelis–Menten equation; time courses are fitted to linear equations. Shown are means and standard errors over at least three independent repeats.

FFold increase (positive values) or decrease (negative values) in the initial uptake rates of the variants relative to WT GltPh. Circles are averages of technical triplicates. Bars are means over independent repeats (as indicated). The dashed line marks a fourfold increase in the initial rate.

Data information: Color coding is the same in all panels. In (D–F), data are colored according to the structural elements where the mutations are located; combination mutants are colored purple. See also Appendix Fig S1 and Appendix Tables S1 and S2.

Here, we generated a repertoire of gain‐of‐function GltPh mutants, in part, through the analysis of systematic amino acid sequence variations among glutamate transporters from organisms living at different temperatures. Our fastest mutant showed the substrate uptake rate ~20‐fold higher than the wild‐type (WT) transporter. Close examination of a representative set of these mutants corroborated previous findings that an increased rate of elevator transitions of the substrate‐loaded transport domain was necessary to increase uptake rate (Akyuz et al, 2015), but also showed that the more dynamic mutants benefited from reduced substrate affinity. At the single‐molecule level, the transport domain dynamics of WT and mutant GltPh were highly heterogeneous, showing a broad distribution of transition frequencies between individual molecules in the population. These apparent dynamic modes parallel the activity modes observed in a recently developed single‐molecule transport assay (Ciftci et al, 2020).

We focused on the dynamic mode in which all examined GltPh variants spend most of their time to probe the most commonly crossed TS structure. All mutations that increased elevator dynamics increased the rate of the OFS‐to‐IFS transitions, but most did not affect the rate of the reverse reaction. Based on these observations, the LFER analysis predicts that the high‐energy TS structurally resembles the IFS. Thus, our data suggest that the transport domain might make multiple attempts at reaching the IFS‐like TS during the OFS residence before progressing to the stable observable IFS. We propose that small molecules with a higher affinity for the IFS than the OFS would also have a higher affinity for the TS. These molecules would, therefore, lower the height of the energy barrier of the OFS to the IFS transition and speed up transport. Our study provides a “recipe” for the possible development of positive allosteric modulators of human transporters.

Results

Gain‐of‐function mutations

Originating from a hyperthermophile, GltPh is a slow transporter (Boudker et al, 2007; Ryan et al, 2009) (Fig 1B). This property is in line with observations that enzymes from thermophilic organisms, which evolved to be stable and functional at high temperatures, show low activity at ambient temperature (Somero, 2004; Elias, Wieczorek et al, 2014). Consistently, glutamate transporters from mesophilic bacteria are more active than GltPh (Tolner, Ubbink‐Kok et al, 1995; Gaillard, Slotboom et al, 1996; Yernool, Boudker et al, 2003; Rahman, Ismat et al, 2017). Also, structurally very similar human EAATs (Canul‐Tec et al, 2017) are ~20 to 10,000‐fold faster (Vandenberg & Ryan, 2013). Interestingly, a “humanizing” R276S/M395R mutation in GltPh, which moves an arginine proximal to the substrate‐binding site from its location in GltPh to that in EAATs, confers an increased transport rate (Ryan, Kortt et al, 2010). Inspired by these considerations, we searched for additional gain‐of‐function mutations by identifying potential evolutionary adaptations to achieve higher activity at lower temperatures. We constructed a multiple sequence alignment of prokaryotic glutamate transporters sorted by the optimum growth temperature of their species of origin and looked for systematic variations between sequences from hyperthermophiles, thermophiles, mesophiles, and psychrophiles (Appendix Fig S1). Overall, we did not observe highly significant systematic changes across all sequences, suggesting that different mutations occurred in different evolutionary lineages. Nevertheless, when we mapped residues with positive global differences scores (Methods and Appendix Table S1) onto the structure of GltPh, we found that the majority formed two clusters in the transport domain centered on HP1 and HP2 (Appendix Fig S1 and Appendix Table S1). Among these, sites with a preference for smaller amino acids in hyperthermophiles were more likely to be taken by larger amino acids in mesophiles and psychrophiles and vice versa (Appendix Table S1). Thus, the packing interactions within the transport domain might play a role during temperature adaptation, consistent with earlier studies where thermophilic and psychrophilic enzymes were, respectively, more rigid and more dynamic than their mesophilic counterparts (Low, Bada et al, 1973; Feller, 2010).

Using this analysis, but also expanding into other regions of the protein (Appendix Fig S1), we selected 30 sites (Fig 1C) and tested the transport activity of 44 single mutants reconstituted into proteoliposomes (Appendix Table S2). A majority showed KM values for l‐Asp similar to the WT KM of 0.5 ± 0.04 μM, but different maximal rates (Fig 1D, Appendix Table S2). We subsequently measured the initial transport rates of all mutants at l‐Asp concentrations of fivefold over the KM values (Fig 1E and F). Five mutations increased the transport rate at least fourfold (Fig 1F, Appendix Table S2). Four of these (A345V, A345S, M362V, and V366A) were in HP2 with A345 and V366 sites identified by the bioinformatics analysis (Appendix Fig S1, Appendix Table S1). All four increased KM at least twofold. The fifth mutation, Y204L GltPh, is located to the kink of TM5 in the scaffold domain (Fig 1A and F, Appendix Table S2). This site did not receive a high score in our analysis because ~80% of the bacterial sequences already have an aliphatic residue at this position, but is notable because the flexibility of the kink might facilitate elevator movements (Verdon & Boudker, 2012). Mutations elsewhere failed to boost transport (Fig 1F, Appendix Table S2). Among these were mutations in and around HP1, suggesting that HP1 and HP2 do not share similar functional roles despite structural pseudosymmetry. Mutations designed to increase interdomain hinge flexibility (P75G and E227G) also did little to boost activity, suggesting that hinges are already sufficiently dynamic even in thermophilic glutamate transporters. Combining the three gain‐of‐function mutations, Y204L, A345V, and V366A produced a mutant with activity 12.7 ± 2.5 times higher than WT GltPh (Fig 1E and F and Appendix Table S2). Thus, subtle packing mutations in HP2 and the scaffold TM5 increase the transport rate by an order of magnitude.

No other combinations produced further rate improvements, including those with the “humanizing” R276S/M395R mutations (Appendix Table S2). To further boost transport, we considered the K290A mutation on HP1 (Fig 1A and E), which disrupts a salt bridge with E192 on the scaffold in the OFS and increases the transport domain dynamics (Akyuz et al, 2013; Georgieva et al, 2013). The K290A mutation by itself did not affect the transport rate. However, when combined with the Y204L/A345V/V366A mutant, it yielded our most active variant with an 18 ± 1 times faster uptake rate than WT GltPh and mean turnover time of ~1 s (Fig 1E and F, and Appendix Table S2).

These robust, 10–20‐fold, increases in transport rate in a set of GltPh variants that contain at most four mutations are in line with similar efforts in enzymology (Renosto, Schultz et al, 1985; Thomas & Scopes, 1998; Johns & Somero, 2004; Dick, Weiergraber et al, 2016; Nguyen, Wilson et al, 2017; Saavedra, Wrabl et al, 2018; Akanuma, Bessho et al, 2019).

Rate limiting steps of the transport cycle

To identify rate limiting features of the transport mechanism, we followed the timing of the transport domain movements between the OFS and IFS by smFRET, using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy (Akyuz et al, 2013; Erkens et al, 2013; Akyuz et al, 2015; Juette, Terry et al, 2016). We labeled a single cysteine mutant (N378C) within the transport domain with self‐healing fluorophores LD555P‐MAL and LD655‐MAL, and biotin–polyethylene glycol–maleimide. We then reconstituted the transporters into proteoliposomes and immobilized them via a streptavidin–biotin bridge in microfluidic perfusion chambers enabling rapid buffer exchange (Appendix Fig S2). We monitored the relative movements of the donor‐ and acceptor‐labeled transport domains within the trimeric transporters at 100‐ms time resolution for a mean duration of ~70 s before photobleaching occurred. Measured FRET efficiency (EFRET) of ~0.4 corresponded to both transport domains in the OFS. EFRET increased to ~0.6 and ~0.9 when, respectively, one or both isomerized into the IFS (Appendix Fig S2). Typically, only one protomer at a time displays recurring transitions between EFRET of ~0.4 and ~0.6 or less often between ~0.6 and ~0.9 during the observation time (Akyuz et al, 2013; Akyuz et al, 2015).

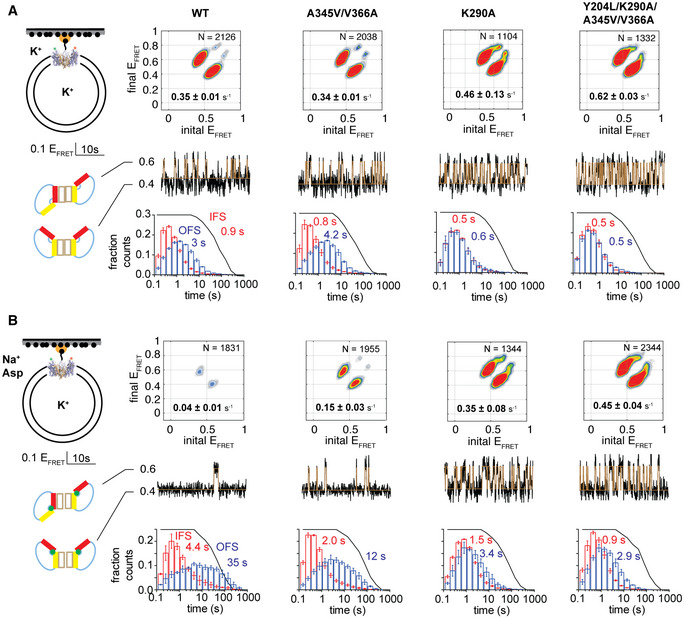

The transport domains shuttled between the OFS and IFS with a mean frequency of 0.35 ± 0.01 s−1 in apo WT GltPh in proteoliposomes in which external and internal buffers contained no Na+ ions or l‐Asp (Fig 2A). The transport domain dynamics were dramatically reduced to a mean frequency of 0.04 ± 0.01 s−1 when we replaced the external buffer with a buffer containing saturating concentrations of Na+ ions and l‐Asp to establish the chemical gradients required for transport (Fig 2B). The dynamics of the GltPh mutants showed similar overall features and trends. All variants exhibited comparatively fast dynamics under apo conditions with frequencies between ~0.24 and 0.6 s−1 (Fig 2A and Appendix Fig S3), which decreased to different extents under transport conditions, except in R276S/M395R GltPh (Figs 2B and Appendix Fig S4). In the presence of 10 mM blocker, d,l‐threo‐β‐benzyloxyaspartic acid (d,l‐TBOA), which should suppress all transitions, we still observed a transition frequency of 0.03 ± 0.01 s−1 in both WT and mutant GltPh proteins (Appendix Table S3). However, these transitions originated from only ~8–17% of all molecules, leading us to suspect that these transitions reflect functionally defective transporters unable to bind d,l‐TBOA, or from spurious blocker dissociation (Akyuz et al, 2013; Akyuz et al, 2015). When we subtracted this small sub‐population from the measured transition frequencies, the resulting frequency for the WT GltPh at room temperature reduced to ~0.01 s−1, on par with the transport turnover rate of 0.06 s−1 measured at 34°C (Appendix Table S2) and the mean single‐transporter rate of 0.01 s−1 measured at 20°C (Ciftci et al, 2020). Overall, these results are consistent with the earlier measurements showing that the substrate‐loaded transport domain is significantly less dynamic than the apo domain and that its movements occur with rates similar to the uptake rates (Akyuz et al, 2013; Akyuz et al, 2015).

Transport domain dynamics under apo (A) and transport (B) conditions

A, BSchematic representations of the experimental conditions are shown on the far left. Data are shown for WT GltPh and select gain‐of‐function mutants, as indicated above the panels. Transition density plots (top of each panel) show the frequency of transitions between the EFRET values. The number of trajectories analyzed (N) and the population‐wide mean frequency of transitions are shown on the panels. Representative 50‐s sections of single‐molecule EFRET trajectories (middle) with raw data in black and idealizations in brown. Scale bar and the conformational states corresponding to the low and intermediate EFRET values are shown to the left of the panels. Dwell‐time distributions for the OFS in blue and the IFS in red (bottom). Mean dwell times are shown on the panels in corresponding colors. Black lines represent photobleaching survival plots normalized from 1 to 0. Shown are means and standard errors over at least three independent repeats. See also Appendix Figs S2–S4.

We observed correlated increases in dynamics and l‐Asp uptake rates in several mutants (Fig 3A). For instance, Y204L/A345V/V366A GltPh showed the mean transition frequency, and the uptake rate increased by 12‐ and 13‐fold, respectively. In contrast, the K290A and K290A/Y204L GltPh mutants showed a ~30‐fold increase in dynamics but no significant changes in activity (Fig 3A). We speculate that substrate release from the IFS becomes rate limiting in these dynamic mutants, with the transport domain visiting IFS multiple times before releasing substrate (Fig 1B).

Correlations between activity, dynamics, and substrate affinity

Changes in the initial rates of substrate uptake (gray bars), transport domain dynamics (black bars), and l‐Asp dissociation constant (white bars) of the mutant GltPh variants relative to the WT transporter. The transition frequencies were measured under non‐equilibrium transport conditions, and frequencies obtained in the presence of d,l‐TBOA were subtracted from the data. Error bars represent standard errors for at least three independent measurements.

Cartoon representation of the crystal structure of Y204L/A345V/V366A GltPh in the presence of saturating concentrations of Na+ ions and l‐Asp (colored as in Fig 1A; PDB accession number: 6V8G) superimposed onto the structure of WT GltPh in the OFS (gray, PDB accession number: 2NWX). l‐Asp and Na+ are shown as spheres and colored by atom type.

Close‐up of the substrate‐binding site. Green mesh represents an omit electron density map for l‐Asp contoured at 4σ. Substrate‐coordinating residues are shown as sticks.

Superimposition of the mutant (colors) and the WT (gray) hairpins aligned on HP1. See also Appendix Figs S4 and S5 and Appendix Tables S2–S4.

The following considerations substantiate the hypothesis. Y204L and K290A did not affect the l‐Asp affinity, consistent with unaltered KM values (Fig 3A and Appendix Fig S5). In contrast, A345V, V366A, and the R276S/M395R mutations reduced affinity ~10, 150, and 40 times, respectively. Most remarkably, combining mutations that dramatically increased the transition frequency (K290A and K290A/Y204L) with those that reduced l‐Asp affinity (A345V and V366A) yielded the fastest GltPh variants (Fig 3A). Therefore, we speculate that A345V, V366A, and R276S/M395R mutations increase the l‐Asp dissociation rates, decreasing the affinity and allowing the mutants to achieve rates limited by the elevator dynamics.

It is, in principle, possible that Na+ and l‐Asp binding to the OFS is rate limiting in the dynamic mutants. However, it is unlikely because Na+ binding to the OFS, rate limiting for l‐Asp binding, occurs within a second under our experimental conditions (Hanelt et al, 2015). Furthermore, we observed dramatically longer OFS dwell times under transport conditions compared to apo conditions (Fig 2). If Na+ binding to the OFS were slow, we would have expected to observe many more apo‐like short OFS dwells, as the domains moved inward before binding solutes. Notably, in our fastest Y204L/K290A/A345V/V366A mutant, achieving turnovers of 1 s, all rate constants become similar, and substrate binding might also impact the transport rate.

HP2 packing mutations A345V and V366A are striking because they both increase the transport domain dynamics and reduce l‐Asp affinity. The altered affinity was unexpected because the residues are located ~14 Å away from the binding site (Appendix Fig S1). The crystal structure of the Y204L/A345V/V366A mutant at ~3.4 Å resolution showed the transporter in an OFS conformation nearly identical to that of the WT (Fig 3B and D, Appendix Table S4). The electron density for l‐Asp was visible, and the amino acid coordination was unaltered (Fig 3C). Interestingly, the unusually high B‐factors of residues in HP2 and the adjacent part of TM8 suggested positional disorder in this region (Appendix Fig S5). One notable difference from the WT structure was the position of the loop connecting TMs 3 and 4. The electron density was unresolved for the bulk of the loop, but a stretch of nine modeled N‐terminal residues ran toward the top of the transport domain, instead of crossing over the HP2 surface as in WT GltPh (Appendix Fig S5). A similar loop conformation was seen in the crystal structure where the transport domain adopted an intermediate position between the OFS and the IFS (Verdon & Boudker, 2012). It remains unclear whether the observed loop conformations are consequences of different crystal packing or have functional implications (Compton, Taylor et al, 2010; Mulligan & Mindell, 2013). Overall, the mutations do not change the structure of HP2 or the binding site but might affect the local dynamics. If so, the reduced affinity could be due to the increased entropic penalty incurred upon substrate binding to a more dynamic apo protein or a less effective water exclusion from the binding site.

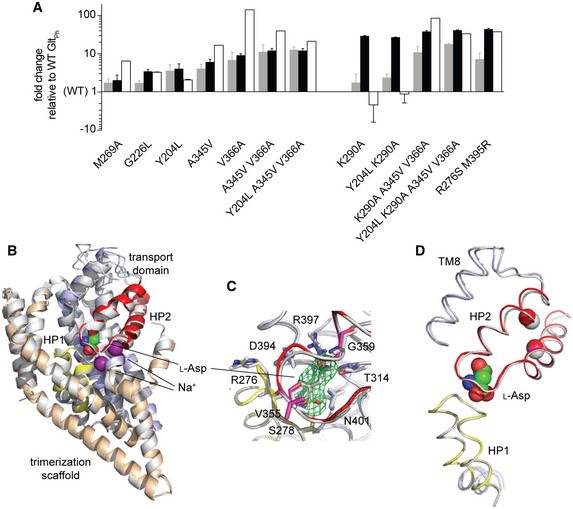

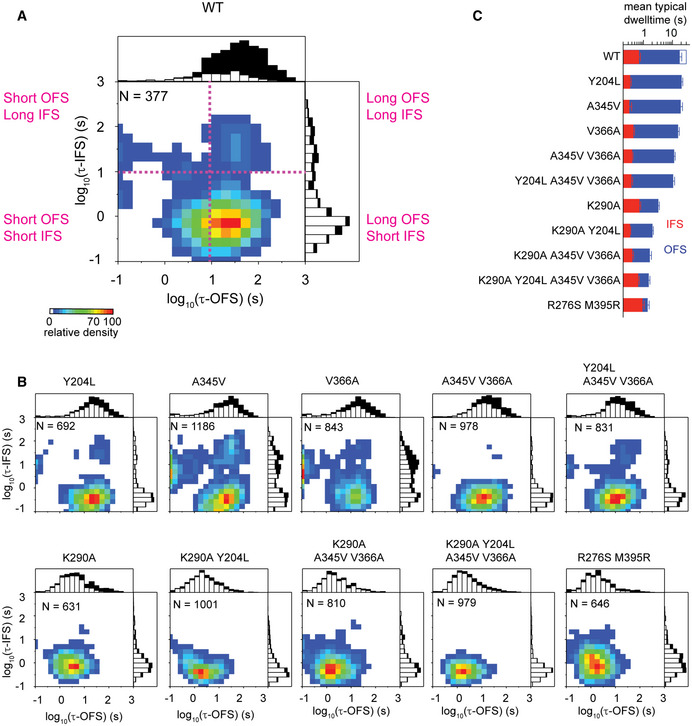

The predominant mode of the transport domain dynamics

We used smFRET recordings at saturating Na+ and l‐Asp concentrations on both sides of the liposomal membrane (Appendix Fig S6) to study the energy barrier controlling the rate of substrate translocation. As observed in earlier studies (Akyuz et al, 2015), WT GltPh dynamics were highly heterogeneous, with the OFS and IFS dwell times ranging from shorter than a second to hundreds of seconds (Fig 4A). At least three exponentials were required to fit the cumulative survival plots (Appendix Fig S6), yielding lifetimes for the OFS of ~3, 20, and 85 s, with each component contributing equally to the fit (Appendix Fig S6). The IFS survival plots showed similar features, except that the short lifetime component was more prevalent (Appendix Fig S6). The longest OFS dwells were shorter in more dynamic mutants, and this change was most dramatic in variants carrying the K290A and R276S/M395R mutations (Fig 4A and Appendix Fig S6). Recordings performed with 10‐ms time resolution showed similar state distributions. They also revealed only a few dwells shorter than 300 ms in the OFS and more in the IFS. Therefore, 100‐ms time resolution is sufficient to capture most, but not all, elevator transitions (Appendix Fig S7). To account for missed transitions, we mathematically corrected the estimated FRET‐state lifetimes following established procedures (Blatz & Magleby, 1986). Consistent with a 100‐ms frame rate being appropriate for the present analyses, missed‐event considerations had little impact on the actual FRET‐state lifetimes.

Kinetic heterogeneity of the transport domain dynamics

Dwell‐time distributions of the OFS (blue) and the IFS (red) for WT (top) and K290A (bottom) GltPh observed under equilibrium conditions in saturating Na+/l‐Asp (left). Lines are fits to three exponentials. Data are averages and standard errors of at least three independent measurements.

Representative EFRET trajectories of WT GltPh showing different transition frequencies. Raw data are in black, and idealizations are in brown. Scale bar is above the trajectories.

Distribution of the WT (top) and the K290A GltPh (bottom) molecules with different mean transition frequencies (white bars). N is the number of trajectories longer than 90 s used in the analysis. The stacked black bars are fractions of trajectories without transitions. Pink bars show the expected binomial distribution if all trajectories shared the mean transition frequency of 0.04 s‐1 for the WT and 0.34 s‐1 for the K290A. Data are averages and standard errors of at least three independent measurements.

2D histograms of the consecutive dwell lengths in the OFS (top) and the IFS (bottom). From left to right: calculated distribution of dwell times randomly selected from the distributions in panel A; measured distribution for WT GltPh and the K290A mutant.

Representative trajectories of the WT (left) and the K290A (right) GltPh molecules showing switching between dynamic modes. Raw data are in black, and idealizations are in brown (top). Black and gray bars under the trajectories indicate apparent slower and faster dynamic modes. Survival plots for the OFS and the IFS (middle). Solid lines are fits to a single (IFS) and double (OFS) exponentials. Dashed lines (OFS only) are rejected fits to single exponentials. Autocorrelation plots of the sequential dwell durations (bottom). Solid lines are fits to single exponentials to guide the eye. See also Appendix Figs S6–S9.

Strikingly, some smFRET traces for the WT transporter showed no or rare transitions, while others featured sustained dynamics (Fig 4B). When we calculated transition frequencies for the individual traces lasting longer than 90 s before photobleaching, we obtained a distribution spanning over two orders of magnitude (Fig 4C). This distribution is significantly broader than would be expected if dwells occurred randomly, with all molecules having the same intrinsic dynamics (Fig 4C). Broader than expected transition frequency distributions were observed for all examined mutants (Fig 4C and Appendix Fig S8). These data indicate that the dynamics of all GltPh variants are characterized by static disorder (Zwanzig, 1990), i.e., distinct kinetic behaviors persist for periods of time comparable to or longer than the observation window. Consistently, we observed correlated lengths of the consecutive dwells in all variants (Fig 4D and Appendix Fig S9).

Importantly, the majority of the individual traces showed intrinsically homogeneous dynamics. Their OFS and IFS survival plots were fitted well by single exponentials (Appendix Fig S10), and their dwell lengths varied randomly around the means as revealed by the flat autocorrelation functions (Lu, Xun et al, 1998) (Appendix Fig S10). Only in a minor fraction of molecules, ranging between 5 and 20 %, survival plots fitted better to two exponentials. Notably, in a subset of these molecules, we observed an apparent switching from one dynamic mode to another, which resulted in autocorrelation functions indicative of temporal segregation of similar dwells (Fig 4E and Appendix Fig S10). These results are generally in agreement with our earlier recordings that showed that the transporters sampled dynamic states and also long‐lasting quiescent states (Akyuz et al, 2015), which we attributed to distinct off‐pathway “locked” conformations. In our current recordings, which are approximately three times longer due to the improved stability of the self‐healing fluorophores (Altman, Zheng et al, 2012; Zheng, Jockusch et al, 2014), we observe that the previously described “locked” states can transition into the IFS, but with low frequency.

Following this analysis, each GltPh transporter with intrinsically homogeneous dynamics can be described by a pair of characteristic OFS and IFS lifetimes mathematically corrected for the missed transitions (Blatz & Magleby, 1986). When plotted on a 2D histogram, they visualize the kinetic heterogeneity of the entire population (Fig 5A and Appendix Fig S11). For WT GltPh, the histogram showed that “typical” molecules had long OFS lifetimes, ranging from ~ 10 to 100 s, and short IFS lifetimes between ~0.5 and 2 s (Fig 5A and Appendix Fig S11). The same kinetic mode prevailed in all of the mutants (Fig 5B and C). Some mutants, most strikingly A345V and V366A GltPh, also had an increased fraction of transporters with long IFS and very short OFS lifetimes (Fig 5B and Appendix Fig S11). At present, the functional significance of these distinct kinetic behaviors is unclear. Consistent with this observation, recently established single‐molecule transport assays have also revealed that WT GltPh exhibits a broad kinetic heterogeneity, with individual transporters showing turnover times between seconds and hundreds of seconds (Ciftci et al, 2020). Thus, the multiple kinetic modes of the conformational dynamics appear to parallel the multiple transport activity modes.

Distributions of the OFS and the IFS lifetime pairs for individual molecules

A, B2D histograms of lifetime pairs obtained for trajectories exhibiting single‐exponential behavior. N is the number of traces used. Scale bar shows relative density normalized by the number of molecules. Above and to the right of each panel are stacked histograms of, respectively, the OFS and the IFS lifetimes of the analyzed molecules (open bars) and the photobleaching time of molecules showing no transitions (black bars). Data from three independent measurements were combined for presentation.

CThe mean lifetimes of the molecules falling within 30% of the most populated bins of the 2D histograms (yellow to red; see Appendix Figure S11 for details). The open blue bar represents the calculated mean OFS lifetime for WT GltPh (see main text for details). Shown are means and standard errors of the mean of at least three independent measurements.

The observed kinetic heterogeneity is unlikely to be due to post‐translational modifications or differences in the lipid environments between individual vesicles because it is reduced under apo conditions (Appendix Fig S12 and Appendix Fig S13). It is also unlikely to arise from incompletely saturated Na+ sites because we used ion concentrations in excess of 200‐fold over the KD values (Reyes, Oh et al, 2013). Instead, we hypothesize that the heterogeneity is indicative of a highly rugged energy landscape and the existence of long‐lived conformations with distinct kinetic properties. Kinetic heterogeneities have been reported in many cases (Auerbach & Lingle, 1986; Xue & Yeung, 1995; Lu et al, 1998; Zhuang, Kim et al, 2002; Nayak, Dana et al, 2011; Min, Jefferson et al, 2018; Zosel, Mercadante et al, 2018). However, they might be particularly pronounced in GltPh because it is a thermophilic protein that might encounter high enthalpic barriers at ambient temperatures. To gain insight into the nature of the most commonly used activation barrier during elevator motions, we set out to perform TS analyses on the predominant observed dynamic mode. Other dynamic modes, such as the one with short OFS and long IFS lifetimes (Fig 5A and B), might have distinct TSs.

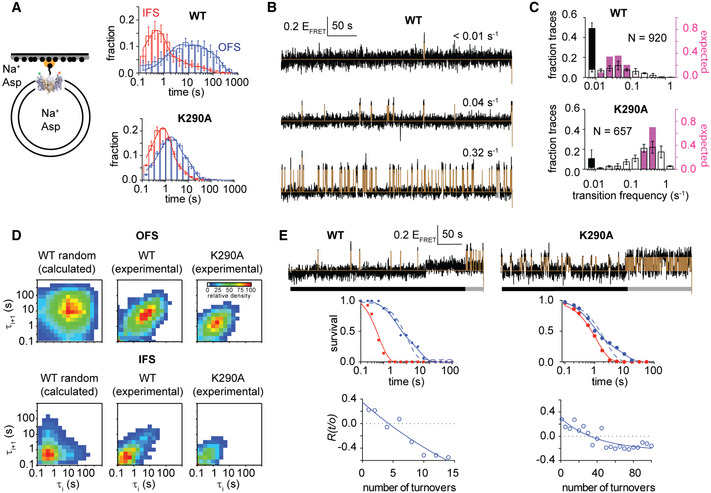

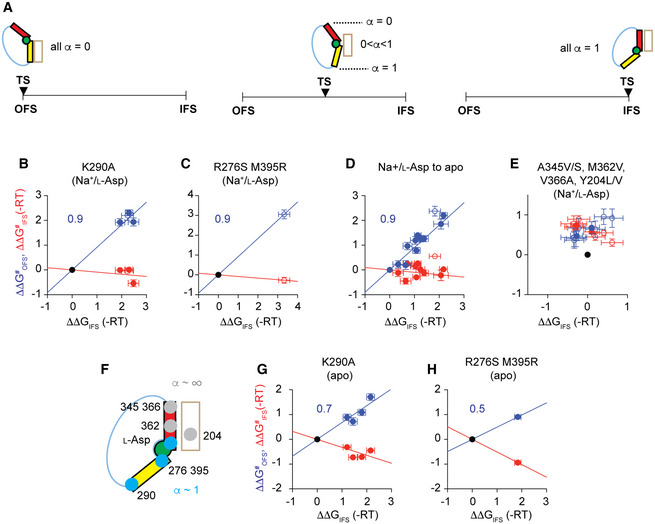

Transition‐state structure

While the macroscopic rates of the transport domain translocation are slow, the translocation process itself is faster than the resolution of our smFRET recordings (10–100 ms). Correspondingly, intermediate positions of the domain, manifesting in intermediate EFRET values, are not observed even though they must be traversed on a faster timescale (Chung, McHale et al, 2012; Chung, Piana‐Agostinetti et al, 2015). The long dwell times in the OFS and IFS arise from the high‐energy barrier that the translocating domain needs to scale. The domain likely makes many failed attempts to cross it before reaching a stable observable state. These brief transitions occur within the conformational ensembles of the OFS and IFS.

Because the transport domain undergoes a concerted, rigid body movement, we applied LFER analysis to infer the structure of the TS in terms of the transport domain position along the trajectory from the OFS to the IFS. LFER analysis correlates changes of the TS free energy relative to the equilibrium end states (i.e., the height of the free energy barrier) to the changes of the free energy difference between the end states in response to perturbations, such as mutations or ligand additions or removals (Appendix Fig S14). The relative free energies of the TS and the end states are inferred from the forward and reverse reaction rate constants. If the TS resembles the OFS, mutations or ligands will change its free energy as much as the free energy of the OFS. If so, the change in free energy of the TS relative to the OFS, ΔΔG# OFS to TS, will be near zero. Thus, the height of the energy barrier crossed during the transition from the OFS to the IFS, and the corresponding forward rate constant, kOFS to IFS, will be unaltered. In contrast, the height of the free energy barrier crossed during the reverse transition from the IFS to the OFS, ΔΔG# IFS to TS, will change as much as the free energy of the IFS relative to the OFS, and the reverse rate constant, kIFS to OFS, will change accordingly (Appendix Fig S14). If, however, the TS resembles the IFS, the above relationships will be reversed. We will observe forward rate constants, kOFS to IFS, that change in response to the perturbations, and reverse rate constants, kIFS to OFS, that do not (Appendix Fig S14). Already a qualitative comparison of the smFRET recordings of WT GltPh in the absence and presence of the substrate and Na+ ions shows that the ligands mostly affect the duration of the OFS dwells (kOFS to IFS). By contrast, the IFS dwells (kIFS to OFS) are unchanged, hinting that the transition state might resemble the IFS (Appendix Fig S14).

Quantitatively, the linear relationship between the equilibrium and the TS free energies is expressed as follows (Evans & Polanyi, 1936; Leffler, 1953; Fersht & Sato, 2004):

where ∆∆GIFS is the change of the free energy of the IFS relative to the OFS. The Leffler α approaches 0 or 1 when the TS resembles the OFS or the IFS, respectively (Fig 6A, left and right). Notably, if the transport domain in the TS assumes an intermediate position between the OFS and IFS, we will obtain different α‐values depending on the location of the perturbation (Fig 6A, middle). Mutations of residues involved in the same interactions in the TS as in the OFS or IFS will yield α‐values of 0 and 1, respectively. Mutating residues involved in interactions distinct from both will yield intermediate α‐values.

Transition‐state analysis

ASchematic representation of the expected Leffler α‐values if the transition state is structurally similar to the OFS (left) or the IFS (right) or if it assumes an intermediate structure (middle). Color coding is the same as in Fig 1.

B–HLFER analysis. Free energy changes plotted in units of ‐RT. The activation free energies of the OFS‐to‐IFS transitions (blue) and the IFS‐to‐OFS transitions (red) were calculated by subtracting the energies of the reference states (black, at the origin) from the energies of the mutated protein variants. The K290A mutation was introduced into the WT, Y204L, A345V/V366A, and Y204/A345V/V366A backgrounds, either substrate‐bound or apo (B and G, respectively). R276S/M395R and M362V mutations were introduced into the WT background (C, E, and H). For the transition from Na+/l‐Asp‐bound to apo state, the free energies measured for the transporters in the presence of Na+ and l‐Asp were subtracted from those measured for the apo transporters (D). Mutations at A345, V366, and Y204 sites and their combinations were introduced within the WT and K290A backgrounds (E). LFERs for the perturbations introduced within the WT background use back‐calculated WT transition rates (see main text, open symbols). Data are averages over at least three independent repeats and errors are propagated from the standard error of the means in each replicate. (F) Schematic summary of sites where perturbations led to changes in the transition‐state energy that scaled with the IFS energy (blue) and where they affected only the transition state (gray). See also Appendix Figs S11–S14.

Our complement of mutants allowed us to test the effects of perturbations along the scaffold‐facing transport domain surface from the cytoplasmic base of HP1 to the extracellular base of HP2. For each, we estimated the rate constants, kOFS to IFS and kIFS to OFS, from the inverse of the mean OFS and IFS lifetimes of the molecules in the predominant dynamic mode (Fig 5B and Appendix Fig S12). First, we examined the effects of the K290A mutation at the base of HP1 (Fig 1A) introduced into the Y204L, A345V/V366A, and Y204L/A345V/V366A background mutants, because their characteristic OFS lifetimes were well determined (Fig 5B). We observed that the K290A mutation shortened the lifetimes of the OFS in these backgrounds (increased kOFS to IFS) by 9 ± 2 times on average but had little effect on the IFS lifetimes (Fig 5C). The free energies of the IFS and the TS decreased similarly by ~ 2 RT relative to the OFS with the Leffler α of 0.91 ± 0.08 (Fig 6B). Therefore, we conclude that the salt bridge between K290 and E192 in the scaffold domain is already broken in the TS. The effect of the K290A mutation on WT GltPh was similar to the other variants with only the OFS lifetime affected (Fig 5C). However, we were unable to measure the WT OFS lifetime directly because it was comparable to the fluorophore lifetime (Fig 5A). We, therefore, assumed that the mutation shortened the OFS lifetime to the same extent in the WT as in the other backgrounds and back‐calculated the WT OFS lifetime to be ~30 s from the lifetime of K290A GltPh. We used this value in comparison with other mutations.

The R276S/M395R mutations at the HP1 tip (Fig 1A) also shifted the equilibrium toward the IFS, reducing the free energy of the TS and the IFS similarly, with the Leffler α of 0.92 (Fig 6C). Furthermore, when we compared the translocation rates of all mutants in the presence of the saturating concentrations of Na+ ions and l‐Asp, and under apo conditions, we obtained mean Leffler α of 0.90 ± 0.05 (Fig 6D). R276 in HP1 and M395 in TM8 face the extracellular and cytoplasmic solutions in the OFS and IFS, respectively, poised to interact with different parts of the scaffold. Furthermore, HP2 undergoes a conformational change in the apo GltPh, which alters the interface between the domains in the IFS, but not in the OFS (Verdon et al, 2014). Thus, our analysis suggests that HP1, HP2, and TM8 form similar interactions in the TS and the IFS. These findings are consistent with the transport domain completing most of the OFS‐to‐IFS movement before overcoming the principal barrier needed to achieve the IFS.

Finally, we examined mutations of A345, M362, and V366 residues on HP2 and Y204 in TM5 kink (Fig 1A). Surprisingly, multiple mutations at these sites led to the increases of both kOFS to IFS and kIFS to OFS within the WT or K290A backgrounds (Fig 6E). Increased rates of both forward and reverse reactions are a hallmark of mutations that stabilize the TS (Otzen, Itzhaki et al, 1994; Fersht & Sato, 2004). Thus, the TS structurally resembles the IFS but is sufficiently distinct so that mutations at Y204, A345, M362, and V366 sites affect the two states differentially (Fig 6F). Notably, when we constructed LFERs for the apo transporters, we observed Leffler α‐values of ~0.7 and ~0.5 for K290A and R276S/M395R mutants, respectively (Fig 6G and H). These results suggest that disrupting the domain interface in the OFS might become a kinetically more critical step when the barrier near the IFS diminishes (Fersht, Itzhaki et al, 1994; Fersht & Sato, 2004; Gopi, Paul et al, 2018).

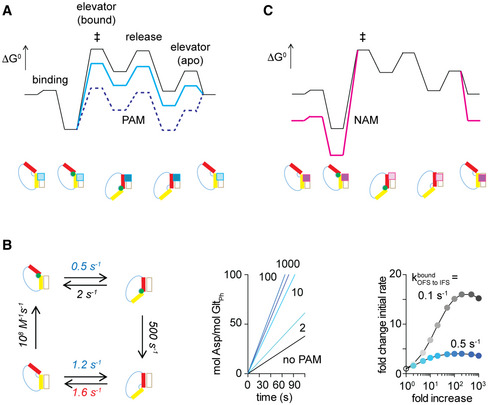

Discussion

To probe the structure of the rate limiting TS for transport domain movement in GltPh, we first identified gain‐of‐function mutations by comparing sequences of homologues from hyperthermophilic, thermophilic, mesophilic, and psychrophilic bacteria. Functional assays and smFRET analyses of these mutants showed that the increased frequency of elevator transitions of the l‐Asp‐bound transport domain and the decreased l‐Asp affinity lead to faster uptake rates. Single‐ and combination‐HP2 mutants and the humanizing R276S/M395R mutant displayed increased dynamics and decreased l‐Asp affinity. Thus, mutations in the transport domain can optimize multiple steps of the transport cycle at once, perhaps mimicking the natural evolutionary process.

Interestingly, the populations of the OFS and IFS in the HP2 mutants remained similar in the absence and presence of l‐Asp and Na+ ions (Appendix Table S5). Thus, their OFS and IFS have similar affinities for the substrate, as is also the case for the WT transporter (Reyes et al, 2013). Therefore, mutations in HP2 affect substrate binding similarly in the OFS and IFS and suggest that HP2 plays a similar gating role in the two states. Crystal structures of WT GltPh in the IFS pictured HP2 immobilized at the domain interface (Reyes et al, 2009; Verdon & Boudker, 2012; Verdon et al, 2014). In contrast, structures of the R276S/M395R GltPh mutant and the human homologue ASCT2 (Akyuz et al, 2015; Garaeva et al, 2019) showed so‐called “unlocked” conformations, in which the transport domain leans away from the scaffold, providing space for HP2 to open. More recently, IFS structures of Na+‐only‐bound GltPh and a closely related GltTk showed that HP2 could open in these unlocked conformations, re‐establishing interactions with scaffold and exposing the l‐Asp‐binding site (Arkhipova, Guskov et al, 2020; Wang & Boudker, 2020). Our results support this “one gate” model (Garaeva et al, 2019), whereby HP2 gates substrate binding in the OFS and the unlocked IFS. Collectively, these data suggest that the conformationally flexible HP2 (Boudker et al, 2007; Huang & Tajkhorshid, 2008; Shrivastava et al, 2008; Grazioso et al, 2012; Heinzelmann et al, 2013; Zomot & Bahar, 2013; Verdon et al, 2014) serves as a master regulator of substrate binding, translocation, release, and recycling of the apo transporter (Kortzak, Alleva et al, 2019).

SmFRET recordings under equilibrium conditions in the presence of saturating Na+ ions and l‐Asp showed that the majority of GltPh molecules resided in the OFS, consistent with earlier studies (Akyuz et al, 2013; Erkens et al, 2013; Georgieva et al, 2013; Hanelt et al, 2013; Akyuz et al, 2015; Ruan et al, 2017). Brief excursions into the IFS intersperse long OFS dwells. Long IFS dwells were also observed in some molecules, and sustained dynamics were seen in others. Overall, we found that the mean transition frequencies vary widely between the individual molecules in the WT and mutant transporters. Such behavior is best described in terms of multiple dynamic modes, whereby molecules show long‐lasting kinetic differences. At present, the structural origins of the heterogeneity are not clear. It might arise from distinct protein conformations, but might also be due, for example, to distinct lipid interactions or other effects.

Linear free energy relationship analysis on nearly all introduced perturbations suggested that the TS for elevator movement structurally resembles the IFS. Hence, once the transport domain dislodges from the scaffold in the OFS, it might make multiple attempts to reach the IFS before successfully crossing the high‐energy barrier. Consistently, subtle packing mutations in HP2 affect both forward and reverse translocation rates, and altered domain interface was observed in the IFS structure of the dynamic R276S/M395R mutant (Akyuz et al, 2015). Thus, we hypothesize that exploring the local conformational space in the IFS‐like TS to achieve a stable configuration of the domain interface is rate‐limiting to the translocation process.

Placing TS within the structural vicinity of the IFS allows us to propose a strategy to develop small‐molecule allosteric modulators for the transporter. We suggest that ligands binding at the domain interface with higher affinity for the IFS than for the OFS would also bind tighter to the TS. Such molecules would reduce the height of the energy barrier for the rate limiting elevator transition of the substrate‐loaded domain and work as activators or positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) (Fig 7A). The degree to which PAMs can accelerate the transport cycle would depend on how much tighter they bind to the TS compared to the OFS and on the height of other, unaffected barriers (Fig 7A and C). In contrast, molecules that bind tighter to the OFS would increase the height of the barrier and serve as negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) (Fig 7B).

Proposed model for allosteric modulation

A, BA free energy diagram of the transport cycle (black) and its modulation (colors) by positive or negative allosteric modulators, PAMs (A) or NAMs (B), respectively. Cartoon representations of the low‐energy states are below the diagrams and are colored as in Fig 1. The barrier heights are not to scale to the measured rates. Substrate binding to the apo OFS precedes isomerization into the IFS via the highest energy TS (‡) that structurally resembles the IFS. Substrate release and recycling into the OFS complete the cycle. PAMs, shown as squares in the cartoons of the states, bind with higher affinity to the IFS (dark cyan squares) than to the OFS (light cyan squares). Therefore, they stabilize all IFS‐like states, including the TS, and smoothen the energy landscape (cyan line). PAMs that bind too tightly to the IFS may become inhibitory, as apo OFS becomes a high‐energy state (dotted blue line). NAMs bind tighter to the OFS ((B), dark magenta squares) than to the IFS (light magenta squares), increase the ruggedness of the landscape (magenta line), and slow down transport.

CSimulations of the transport rates in the absence and presence of PAMs. The left panel shows the transport cycle with the used rate constants (Materials and Methods). PAM effects were considered equal on both OFS‐to‐IFS isomerizations (blue rate constants). The acceleration of transport becomes rate‐limited by the IFS‐to‐OFS isomerization of the apo transporter as PAM action increases OFS‐to‐IFS isomerizations (red rate constant). Middle and right panels show simulated uptake and fold increase in the initial rates, respectively, in the presence of PAMs that increase kOFS to IFS by the indicated number of folds (from cyan to dark blue). Simulations of cycles with = 0.1 s‐1 illustrate higher PAM potency (gray).

PAMs of human EAATs could offer therapeutic opportunities to treat a plethora of conditions associated with glutamate‐mediated excitotoxicity in the central nervous system (Fontana, 2015), but a rationale is lacking to aid their development. Similar to our most performant gain‐of‐function GltPh mutant (Fig 7C), substrate binding and release are fast compared to the elevator movements in EAATs (Mim, Tao et al, 2007). However, in contrast to GltPh, the return of the K+‐bound transport domain from the IFS to the OFS is the rate‐limiting step (Grewer, Watzke et al, 2000). We stipulate that if the TS of this translocation reaction resembles the OFS structurally, small molecules that bind tighter to the OFS will act as PAMs. Recently developed compounds boost EAAT2 transport by ~2‐fold (Kortagere, Mortensen et al, 2018; Falcucci, Wertz et al, 2019) and have features that agree with the concepts developed here. Indeed, the identified PAMs are thought to bind preferentially to the domain interface in the OFS (Kortagere et al, 2018; Falcucci et al, 2019). Moreover, chemically similar compounds act as activators or as inhibitors (Kortagere et al, 2018), as predicted by our model. However, further work is necessary to reveal the structural features of the TS for the IFS‐to‐OFS transitions in K+‐bound EAATs.

Approximately 50 % of solute carriers are implicated in disease in humans, but only a few are drug targets (Rask‐Andersen, Masuram et al, 2013). Our approach conceptualizes how the rate‐limiting transition state of a transporter can be characterized structurally, informing on potential druggable sites to develop allosteric modulators, and provides a method to investigate the kinetic effects of post‐translational modifications (Czuba et al, 2018). We anticipate that our methodology can be adapted to accelerate the expansion of therapeutic allosteric modulators in other protein systems with conformationally selective pockets, such as kinases (Hammam, Saez‐Ayala et al, 2017; Zorba, Nguyen et al, 2019).

Materials and Methods

Bioinformatics analysis

The workflow of the bioinformatics approach is in Appendix Fig S1. Organism taxa, optimal growth temperatures, and temperature limits for growth were extracted from BacDive (Reimer, Vetcininova et al, 2019). Sequences of 20,000 prokaryotic homologues of GltPh were collected using BLAST (Altschul, Madden et al, 1997) and aligned using MAFFT 7.0, applying the highest gap penalty (Katoh, Misawa et al, 2002). Multiple sequence alignments (MSA) were manually adjusted to optimize the alignment of the secondary structure elements and to remove sequences that were lacking one or more transmembrane helices. Sequences with over 90 % amino acid sequence identity were clustered using USEARCH (Edgar, 2010), and one random sequence per cluster was retained for subsequent analysis. Optimal growth temperatures and temperature limits were assigned to the sequences by matching GenInfo identifiers with genus and species annotations in BacDive database. Sequences without a match were excluded from further analysis. The remaining sequences were sorted into four temperature groups: psychrophiles (growth temperatures below 21°C), mesophiles (21°C–45°C), thermophiles (46°C–65°C), and hyperthermophiles (over 65°C). All temperature groups, except mesophiles, were manually sorted to exclude sequences originating from organisms with growth temperature ranges spanning more than two temperature groups. This process yielded 128, 58, 11, 93, and 24 sequences from psychrophiles, mesophiles, thermophiles, and hyperthermophiles, respectively. The amino acid frequencies were calculated at each position in the MSA for all temperature groups using Prophecy (Rice, Longden et al, 2000) and using the GltPh sequence as a reference. Combined frequencies were calculated for amino acids classified by their physicochemical properties (A + V, G, S + C+T + N+Q, P, D + E, H + M, Y + W, F + L+I, K + R) or side chain volumes (A + G+S, P + C+T + N+D, H + E+Q + V, Y + W+F, M + L+I + K+R). We used the outcomes of two‐sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests to determine whether amino acid distributions at each position of the MSA were statistically different between pairs of temperature groups. Because no position showed significant distribution changes across all temperature groups, the results of every pairwise comparison in the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test were weighted to reflect the temperature gap between the groups (i.e., multiplied by 3 for the comparison between the hyperthermophiles and psychrophiles, and 2 for thermophiles and psychrophiles). A positive value of the sum of the weighted values (global difference score) for a given position in the MSA indicates a change of the amino acid distribution correlated to the optimal growth temperature. Among the amino acids with positive global difference score, mutation sites were selected according to the following criteria: (i) Their side chains were not exposed to either aqueous solution or lipid bilayer; (ii) they were in well‐conserved regions; and (iii) they were not directly coordinating l‐Asp or Na+ ions. Additional residues in these areas were chosen to perturb packing interactions (I85, L303, T322, I341, and M362). Differences in the crystal structures of WT GltPh in the OFS and the IFS were used to guide mutagenesis of several residues in the interdomain hinges (A70, P75, Q220, H223, G226, and E227) and TM2/5 kink (D48 and Y204). GltPh residues were mostly mutated to those prevalent in mesophiles or psychrophiles, in most cases producing conservative mutations that lead to subtle volume changes or the removal of hydrogen bonds.

Mutagenesis, protein expression, purification, and labeling

Amino acid substitutions were introduced by site‐directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) in a GltPh variant with seven non‐conserved surface‐exposed residues replaced with histidines to increase expression yields (referred to as wild‐type; Yernool et al, 2004). For smFRET microscopy, substitutions were introduced within the GltPh variant with additional C321A and N378C mutations, as previously described (Akyuz et al, 2013). Constructs were cloned in‐frame into pBAD24 vector with a C‐terminal thrombin cleavage site followed by octa‐histidine tag as described previously (Yernool et al, 2004) and verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmids were transformed into E. coli strain DH10B (Invitrogen), and protein expression was induced for 3 h at 37°C by 0.1 % arabinose. GltPh was purified from cell membranes, as described previously (Yernool et al, 2004). Briefly, membranes were solubilized in a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM l‐Asp, and 40 mM n‐dodecyl‐β‐d‐maltopyranoside (DDM, Anatrace). Insoluble material was removed by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C. Solubilized transporters were bound to nickel agarose (Qiagen) for 2 h at 4°C. The resin was washed in the same buffer containing 1 mM DDM and 40 mM imidazole and proteins eluted with 250 mM imidazole. The tag was removed by overnight cleavage with thrombin at room temperature using 10 units per mg GltPh. The proteins were further purified by size‐exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GL column in buffers of various compositions: 10 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM l‐Asp, and 7 mM n‐decyl‐β‐d‐maltopyranoside (DM, Anatrace) for transport assays; 10 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM l‐Asp, and 5 mM DM for crystallization; 10 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 1 mM NaCl, 200 mM choline chloride, and 1 mM DDM for binding assays; and 10 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM l‐Asp, and 1 mM DDM for smFRET microscopy. When GltPh proteins were purified for smFRET microscopy, all buffers were supplemented with 0.1 mM Tris(2‐carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP). GltPh purity was confirmed by SDS–PAGE, followed by Coomassie Brilliant Blue R‐250 staining. For smFRET studies, purified GltPh variants at 40 µM were labeled randomly with maleimide‐activated LD555P‐MAL and LD655‐MAL dyes (Altman et al, 2012; Zheng et al, 2014) and biotin‐PEG11 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at final concentrations of 50, 100, and 25 μM, respectively, as previously described (Akyuz et al, 2013). Labeling efficiency was determined by spectrophotometry using extinction coefficients of 57,400, 150,000, and 250,000 M−1 cm−1 for GltPh, LD555P‐MAL, and LD655‐MAL, respectively. Excess dyes were removed on a PD MiniTrap Sephadex G‐25 desalting column (GE Healthcare).

l‐Asp binding assays

Fluorescence‐binding assays were performed as described previously (Verdon et al, 2014). Briefly, GltPh was diluted to a final concentration of 2 μM in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM choline chloride, 0.4 mM DDM, and 0.4 nM RH421 dye (Invitrogen) supplemented with 1 or 10 mM NaCl, as indicated. RH421 was excited at 532 nm, and emission was measured at 628 nm at 25 °C using a QuantaMaster fluorometer equipped with a magnetic stirrer (Photon International Technologies). Fluorescence changes induced by additions of l‐Asp aliquots were monitored until stable for ~100 s, corrected for dilution, and normalized to the maximal fluorescence change. Binding isotherms were plotted and fitted to the Hill equation using Prism (GraphPad). All measurements were performed in triplicate.

GltPh reconstitution into liposomes and transport assays

GltPh variants were reconstituted into liposomes as described previously (Yernool et al, 2003). Liposomes were prepared using E. coli polar lipid extract, egg yolk l‐α‐phosphatidylcholine, and 1,2‐dioleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphoethanolamine‐N‐(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) (Avanti Polar Lipids) in a 3,000:1,000:1 (w/w/w) ratio. The dried lipid films were hydrated in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM KCl, 100 mM choline chloride at a final concentration of 70 mM lipid by repeated freeze–thaw cycles. Liposomes were extruded through polycarbonate filters with a pore size of 400 nm (Avanti Polar Lipids) and destabilized with Triton X‐100 (Sigma) at a detergent‐to‐lipid ratio of 0.5:1 (w/w). GltPh variants were added at final protein‐to‐lipid ratios of 1:2000 (w/w) and incubated for 30 min at 22°C. Detergents were removed by repeated incubations with Bio‐Beads SM‐2 (Bio‐Rad). Liposomes were concentrated by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C, subjected to three freeze–thaw cycles, and extruded through 400‐nm polycarbonate filters (Avanti Polar Lipids). To initiate transport, liposomes were diluted 100‐fold into a buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM KCl, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5 μM valinomycin, and variable concentrations of 3H‐l‐Asp (aspartic acid, L‐[2,3‐3H], PerkinElmer). When necessary, the reaction mixtures were supplemented with cold l‐Asp. At appropriate time points, 200 μl aliquots were removed and diluted into ice‐cold quench buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM LiCl, and 100 mM choline chloride, followed by rapid filtration using 0.22‐μm nitrocellulose filters (Whatman). Filters were washed three times using a total of 8 ml quench buffer. The retained radioactivity was measured by scintillation counting in a LS‐6500 counter (Beckman Coulter). To determine l‐Asp KM, concentration dependences were measured using 1‐min incubation to achieve robust signals for all variants. Uptake time courses were measured at concentrations of l‐Asp of 5 times over KM for 90 s. All uptake experiments were performed at 34°C. The background was determined in the reaction buffer lacking NaCl and subtracted from the measurements. The proteoliposome concentration was determined by measuring rhodamine fluorescence using excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 and 590 nm, respectively. The protein concentration was estimated by assuming similar reconstitution efficiencies for all GltPh variants. The amount of l‐Asp uptake was normalized per GltPh monomer. Dose–response curves and initial time courses were plotted and fitted in Prism (GraphPad).

Crystallography

Purified Y204L/A345V/V366A GltPh mutant was concentrated to 3 mg/ml. Protein was mixed 1:1 with a reservoir solution containing 100 mM potassium citrate pH 4.4–5 and 12–17% PEG 400. The protein was crystallized at 4°C by hanging‐drop vapor diffusion method. Crystals were cryo‐protected in reservoir solution supplemented with 30–35% PEG 400. Diffraction data were collected at Advanced Light Source beamline 8.2.2. Diffraction data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using HKL2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997). Initial phases were determined by molecular replacement in Phaser (McCoy, Grosse‐Kunstleve et al, 2007) using 2NWX as the search model. The model was optimized by iterative rounds of refinement and rebuilding in Phenix (Adams, Grosse‐Kunstleve et al, 2002) and Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004). Strict non‐crystallographic threefold symmetry was applied during refinement.

smFRET microscopy and data analysis

GltPh was reconstituted into liposomes as above with modifications. The 1,2‐dioleoyl‐sn‐glycero‐3‐phosphoethanolamine‐N‐(lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl) was omitted, and the lipid film was hydrated in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, and 200 mM KCl. GltPh was added at a final protein‐to‐lipid ratio of 1:1,000 (w/w) to maximize the number of liposomes containing one trimer. Liposomes were extruded through 100‐nm polycarbonate filters (Avanti Polar Lipids). To replace internal liposome buffer, vesicles were subjected to three rounds of the following procedure. Proteoliposomes were pelleted by centrifugation for 40 min at 100,000 g at 4°C, resuspended in buffer containing 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl or 20 mM Hepes/Tris, pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM l‐Asp, as required, and subjected to a freeze/thaw cycle.

All smFRET experiments were performed on a home‐built prism‐based total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope constructed around a Nikon Eclipse Ti inverted microscope using passivated microfluidic imaging chambers (Munro, Altman et al, 2007; Juette et al, 2016). The samples were illuminated with a 532‐nm laser (Laser Quantum). LD555P and LD655 fluorescence signals were separated using a T635lpxr dichroic filter (Chroma) mounted in a MultiCam apparatus (Cairn). Imaging data were acquired using home‐written acquisition software and scientific complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor (sCMOS) cameras (Hamamatsu).

Labeled GltPh variants in proteoliposomes were surface‐immobilized via a biotin–streptavidin bridge on PEG‐passivated microfluidic imaging chambers functionalized with streptavidin. Imaging experiments were performed in 20 mM Hepes/Tris buffers at pH 7.4 containing 5 mM β‐mercaptoethanol and an oxygen scavenger system comprised of 1 U/ml glucose oxidase (Sigma), 8 U/ml catalase (Sigma), and 0.1 % glucose (Sigma). Experiments under symmetric apo conditions were performed in buffer supplemented with 200 mM KCl using proteoliposomes loaded with buffer containing 200 mM KCl. Under non‐equilibrium transport conditions, imaging buffer was supplemented with 200 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM l‐Asp. For symmetric saturating Na+/l‐Asp conditions, the internal liposome and imaging buffers contained 200 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM l‐Asp. To inhibit protein dynamics, liposomes containing 200 mM NaCl were incubated in imaging buffer containing 200 mM NaCl and 10 mM d,l‐TBOA. Data were collected using 10‐ or 100‐ms averaging time. Single‐molecule fluorescence trajectories were selected for analysis in SPARTAN (Juette et al, 2016) implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks). Trajectories were corrected for spectral bleed‐through from donor to acceptor channel by subtracting a fraction of the donor intensity from the acceptor (0.168). Acquired traces were selected for analysis using the following criteria: a single catastrophic photobleaching event, ascertaining GltPh labeling with a single LD555P‐MAL and LD655‐MAL label; over 10:1 signal‐to‐background noise ratio; over 5:1 signal‐to‐signal noise ratio; FRET lifetime of at least 5 s; and a maximum of 1 donor blink per trajectory. FRET trajectories were calculated from LD555P and LD655 intensities, ID and IA, respectively, using EFRET = IA/(ID + IA). Population contour plots were constructed by superimposing EFRET from individual trajectories and fitted to Gaussian distributions in Prism (GraphPad). Dwell‐time distributions and transition frequencies were obtained by idealizing EFRET trajectories in SPARTAN (Juette et al, 2016). State survival plots and dwell‐time histograms were fitted to double or triple exponentials and the probability density functions (Sigworth & Sine, 1987), respectively. Analyses of transition frequencies, dwell times, and survival plots for individual trajectories were performed using custom‐made scripts implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks). State survival plots of individual trajectories were fitted to single exponentials or double exponentials if R2 increased by at least 5 %, and the time constants differed at least fivefold. Fits were only performed when traces contained at least 5 visits to the OFS or the IFS. Mean dwell times were used otherwise. For illustration purposes, state survival plots of selected molecules were refitted in Prism (GraphPad). 2D histograms were generated in Origin (OriginLab). The autocorrelation coefficients R(t/o) of the dwell durations as functions of the number of consecutive state visits were calculated as , where t/o are the number turnovers, τi the dwell lengths, and <τ> the average dwell time over the trajectory (Lu et al, 1998). Each experiment was performed at least in triplicate using independent protein reconstitutions and buffer preparations. In each experiment, a minimum of 400 molecules was selected.

Transition‐state analysis

LFER analysis builds on observations from reaction chemistry (Evans & Polanyi, 1936; Leffler, 1953), which correlate changes of the rate constants with changes of the equilibrium constant upon perturbations of the start and end equilibrium states. Here, the free energy change of the transition state, ∆G#, is expected to fall between the free energy changes of the equilibrium end states, the OFS and the IFS, following perturbations (Leffler, 1953):

where ΔΔG# OFS to IFS is the activation energy of the transition from the OFS to the IFS. The activation energy of the reverse reaction can be expressed similarly:

The equilibrium free energy change is calculated from equilibrium constants before and after the perturbation, KR and KP (where R and P stand for “reference” and “perturbation”), respectively:

The equilibrium constants are obtained as ratios of the forward and reverse rate constants kOFS to IFS and kIFS to OFS measured before and after the perturbation. The transition‐state energy changes can be approximated as in Kramers theory assuming that the transition mechanism (i.e., the shape of the energy barrier) is not altered by the perturbation (Kramers, 1940):

ΔΔG#IFS to OFS is calculated in an analogous manner from the reverse reaction rates.

Kinetic modeling of the transport cycle

The transport cycle for WT GltPh was simulated in COPASI (Hoops, Sahle et al, 2006). A two‐compartment system was created to reflect external and internal proteoliposome space. The initial conditions were 200 mM Na+ and 1 mM l‐Asp in the external space with all transporters in the apo state and the fraction of the OFS at 0.6. External substrate binding and internal substrate release were approximated as irreversible. External substrate binding was arbitrarily set to 108 M‐4s‐1, while internal release was set to an estimated value of 500 s‐1 (Oh & Boudker, 2018). Rate constants for the conformational changes were estimated from the mean lifetimes of “typical” Y204L/K290A/A345V/V366A GltPh molecules analyzed by smFRET and set at kOFS to IFS, apo = 1.2 s‐1, kIFS to OFS, apo = 1.6 s‐1, kOFS to IFS, bound = 0.5 s‐1, and kIFS to OFS, bound = 2.0 s‐1. The effect of a positive allosteric modulator on kOFS to IFS, bound and kOFS to IFS, apo was considered the same, and the increase in transport rate was simulated for 2‐, 5‐, 10‐, 20‐, 50‐, 100‐, 200‐, 500‐, and 1,000‐fold increases of kOFS to IFS, bound and kOFS to IFS, apo. Time courses were simulated over 1,000 s.

Statistical analysis

All data reflect the means and standard deviation over at least three replicates. The standard error of the mean was used for the typical OFS and IFS lifetimes.

Author contributions

GHMH and OB conceived the study. GHMH acquired the data. GHMH, DC, XW, and OB analyzed the data. OB and SCB collected the resources. GHMH and OB wrote the manuscript with input from all other authors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roger Altman for preparation of smFRET chambers, Zhou Zhou for dye formulations, Eva Fortea and Emma Garst for assistance with crystallization trials, and Lucy Skrabanek for R scripts used in bioinformatics sequence analysis. We thank Julia Chamot‐Rooke for continued support. We are grateful for the support of NINDS (R37NS085318 to O.B. and S.C.B.) and AHA (19PRE34380215 to H.D.C.). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska‐Curie grant agreement MEMDYN No 660083 (to G.H.M.H.).

Data availability

The structure of Y204L A345V V366A GltPh has been submitted to the PDB (accession code: 6V8G; http://identifiers.org/pdb/6V8G).

The high‐energy transition state of the glutamate transporter homologue GltPh

The high‐energy transition state of the glutamate transporter homologue GltPh