- Altmetric

Herein, we demonstrate a novel one‐pot synthetic method towards a series of boron‐doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (B‐PAHs, 1 a–1 o), including hitherto unknown B‐doped zethrene derivatives, from ortho‐aryl substituted diarylalkynes with high atom efficiency and broad substrate scopes. A reaction mechanism is proposed based on the experimental investigation together with the theoretical calculations, which involves a unique 1,4‐boron migration process. The resultant benchtop‐stable B‐PAHs are thoroughly investigated by X‐ray crystallography, cyclic voltammetry, UV/Vis absorption, and fluorescence spectroscopies. The blue and green organic light‐emitting diode (OLED) devices based on 1 f and 1 k are further fabricated, demonstrating the promising application potential of B‐PAHs in organic optoelectronics.

A novel one‐pot synthetic strategy towards a series of boron‐doped polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from ortho‐aryl substituted diarylalkynes has been developed. A reaction mechanism is proposed based on the experimental investigation together with the theoretical calculations, which involves an unprecedented 1,4‐boron migration process.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) have intrigued significant interest due to their promising applications in organic electronics and spintronics, [1] such as organic light‐emitting diodes (OLEDs) [2] and organic field‐effect transistors (OFETs), [3] etc. In the past two decades, extended PAHs with different sizes and edge structures have been successfully achieved through the bottom‐up organic synthesis, in which their chemical reactivities and optoelectronic properties are tailorable by their topological structures.[ 1c , 4 ] The introduction of heteroatoms into the lattice of sp 2‐carbon frameworks presents an effective strategy to tune the intrinsic physicochemical properties of PAHs, such as the chemical reactivity, energy gaps, and redox behavior.[ 1f , 5 ] Among them, bottom‐up synthesis of well‐defined boron‐doped PAHs (B‐PAHs) has entered into a new stage for the development of novel PAHs with improved electron affinities and luminescence behavior. [6] Although significant efforts have been made in the past few years, [7] the modular synthetic routes to B‐PAHs, particularly for dual‐B doped PAHs, remain limited due to the intrinsic instability of B‐PAHs against moisture and oxygen. [6a] In 2015, Wagner et al. reported the synthesis of B‐PAHs via a Si/B exchange reaction (Figure 1 a). [7c] Later, Ingleson and co‐workers demonstrated a synthetic route toward B‐PAHs through a combined borylative cyclization and electrophilic C−H borylation (Figure 1 b). [7e] More recently, a synthetic access to B‐PAHs from naphthalene‐ and pyrene‐based alkenes was disclosed by Würthner et al. (Figure 1 c). [7f] Despite the achieved progress, the aforementioned methods involve special precursor or multiple synthetic steps, e.g., an additional oxidation etc., resulting in low overall yields of synthetic procedures. Thereby, it is highly attractive to develop cost‐effective methodologies for the synthesis of B‐PAHs from the readily available starting compounds.

Herein, we report a novel one‐pot synthetic method toward a series of mono/dual B‐PAHs (1 a–1 o) via an unprecedented 1,4‐boron migration process from ortho‐aryl substituted arylalkynes (Figure 1 d). This protocol renders a broad scope of substrates with high atom efficiency and functional group tolerance. For instance, the yields for mono and dual B‐doped PAHs are up to 46 % (1 c) and 40 % (1 k), respectively. The reaction mechanism involves a sequence of borylative cyclization, 1,4‐boron migration, and electrophilic C−H borylation. Significantly, the 1,4‐boron migration plays a critical role in the formation of B‐PAHs, which is further supported by controlled experiments and theoretical calculations. Notably, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first example regarding the 1,4‐boron migration in the π‐conjugated system. The structures of the resultant B‐PAHs are unequivocally confirmed by multinuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and high‐resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) characterizations. Single‐crystal X‐ray analysis of 1 b and 1 k demonstrate that the boron atom locates at the zigzag edge and adopts a trigonal planar geometry. The achieved B‐doped compounds 1 a–1 o display excellent fluorescence with the photoluminescence (PL) quantum yields (Φ PL) up to 97 % in dichloromethane solution (1 g) and 91 % in the solid‐state thin film (1 f).[ 7a , 7c , 7d , 7e , 7f ] As a proof‐of‐concept study, blue and green OLEDs are fabricated based on B‐PAHs 1 f and 1 k with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 3.5 % and 3.2 %, respectively, demonstrating their promising applications in organic optoelectronic devices.

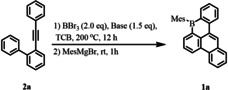

As the starting point, 2‐(phenylethynyl)‐1,1′‐biphenyl (2 a) was investigated firstly as the model substrate (Table 1). Boron tribromide (BBr3) was added into a solution of 2 a and 2,4,6‐tri‐tert‐butylpyridine (TBP) in 1,2,4‐trichlorobenzene (TCB). Then the mixture was heated at 200 °C for 12 h. Subsequently, followed by the workup with mesitylmagnesium bromide (MesMgBr) at the room temperature, 8‐mesityl‐8H‐benzo[e]phenanthro[1,10‐bc]borinine (1 a) was directly achieved with an isolated yield of 43 % (Table 1, Entry 1). It is worth noting that the bulky Brønsted base plays an important role in the formation of 1 a. For instance, when sterically less demanding (triethyl)amine (Et3N) was used as the base, 1 a was not observed (Table 1, Entry 2). Less bulky bases 2,6‐di‐tert‐butylpyridine and 2,2,6,6‐tetra‐methylpiperidine provided relatively lower yield than that with the base TBP (Table 1, Entry 3 and 4).

|

Entry |

Base |

Solvent |

1 a [%][a] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

2,4,6‐Tri‐tert‐butylpyridine |

TCB |

43 |

|

2 |

(Triethyl)amine |

TCB |

ND[b] |

|

3 |

2,6‐Di‐tert‐butylpyridine |

TCB |

28 |

|

4 |

2,2,6,6‐Tetramethylpiperidine |

TCB |

Trace[c] |

[a] Isolated yield. [b] No desired compound was detected. [c] Trace amount of 1 a was detected.

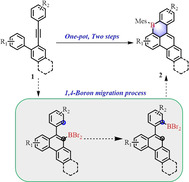

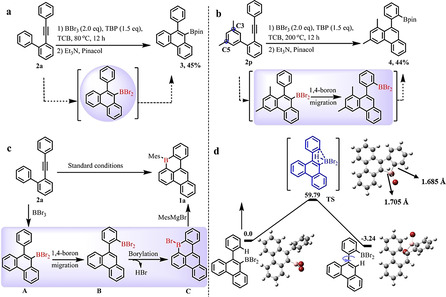

In order to gain an in‐depth understanding on the mechanism for the formation of 1 a, treatment of 2 a with BBr3 at 80 °C for 24 h followed by workup with Et3N and pinacol provided boronic ester 3 with 45 % yield (Scheme 1 a). This result suggested that the dibromo(10‐phenylphenanthren‐9‐yl)borane could be the possible intermediate. Furthermore, to examine the 1,4‐boron migration process, compound 2 p was designed, in which two methyl groups can block the C3 and C5 sites during the electrophilic borylation process (Scheme 1 b). Remarkably enough, when 2 p was treated under 200 °C, pinacol boronic ester 4 was isolated as the primary product in 44 % yield. This controlled experiment clearly elucidates that the 1,4‐boron migration process is involved during the reaction. Based on these experimental results and well‐investigated benzene annulation chemistry of arylacetylenes, [8] a possible mechanism is proposed for the formation of 1 a as presented in Scheme 1 c: firstly, the intermediate A is formed through the 6‐endo‐dig borylative cyclization of alkyne 2 a in the presence of BBr3. [9] Subsequently, A undergoes 1,4‐boron migration to afford intermediate B, followed by an electrophilic borylation to generate the six‐membered boracycle C. Finally, desired B‐doped 1 a is achieved after workup with the MesMgBr. The critical step, 1,4‐boron migration process in this proposed mechanism, can be further supported by the intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations (Scheme 1 d). [10] The theoretical results indicate that 1,4‐boron migration is not a stepwise but rather a concerted process and occurs via a transition states (TS) with an activation energy (ΔG) of 59.79 kcal mol−1 in vacuum conditions (Figure S80).

a) and b) Controlled experiments to demonstrate 1,4‐boron migration process; c) Proposed mechanism for the synthesis of B‐doped 1 a; d) DFT calculation for the 1,4‐boron migration process (unit: kcal mol−1) B pink, Br red.

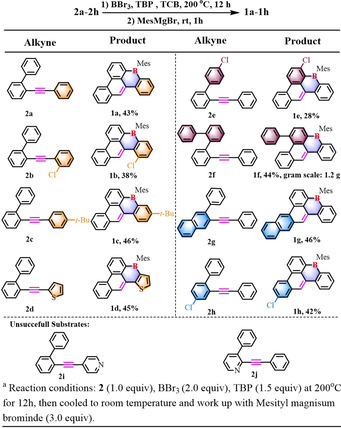

To further demonstrate the applicability of this one‐pot synthesis method, a variety of substituted 2‐(phenylethynyl)‐1,1′‐biphenyl were examined (Table 2). Most of the alkynes engaged in the unique 1,4‐boron migration process, providing the corresponding B‐PAHs 1 a–1 h in moderate yields from 28 % (1 e) to 46 % (1 c, 1 g). It was found that the nature of the substrates presents a significant effect on the formation of B‐doped PAHs. In general, electron‐rich substrates (2 c, 2 d, 2 f, and 2 g) promote the formation of corresponding products (1 c, 1 d, 1 f, and 1 g) with higher yields, whereas electron‐deficient substrates display seriously negative effect. For instance, no reaction occurred for 2 i and 2 j containing the pyridine substituent (Table 2). Noteworthily, our method could furnish B,S co‐doped PAH 1 d in 45 % yield from 2‐([1,1′‐biphenyl]‐2‐ylethynyl)thiophene (2 d). In addition, chloro‐substituent can be tolerated under current conditions (1 b, 1 e, and 1 h), providing the possibility for the post‐functionalization of this family of B‐PAHs.

|

|

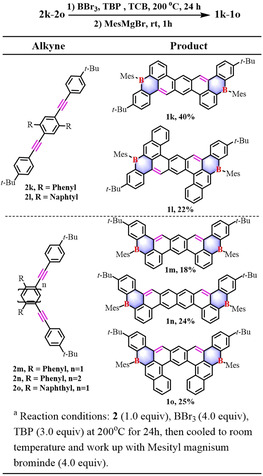

Inspired by the successful synthesis of B‐PAHs 1 a–1 h with one boron center, thereupon, large B‐PAHs containing two boron centers were targeted. To our delight, π‐extended dual B‐PAHs 1 k–1 n were successfully achieved from their corresponding alkynes 2 k–2 n with the yields of 18–40 % (Table 3). Remarkably, bench‐top stable compounds 1 k and 1 l are the first examples of B‐doped zethrene derivatives with rich zigzag edges, which stand in contrast to their pristine open‐shell counterparts. [11] Moreover, this synthetic method can be further exploited for the preparation of B‐PAHs with a helical structure. For instance, helical B‐PAHs 1 o was synthesized in 25 % yield from compound 2 o (Table 3). Satisfactorily, this synthetic strategy can be scaled up to a gram scale (1 f, 1.2 g). All the compounds 1 a–1 o are fully characterized by HRMS and NMR analysis (Figure S23–S53).

|

|

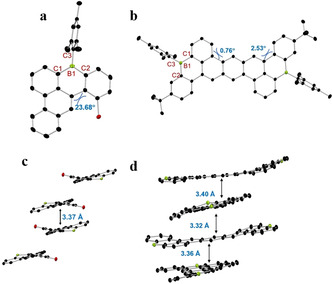

The chemical structures of representative compounds, mono‐B doped 1 b, and dual‐B doped 1 k, were unequivocally confirmed by X‐ray crystallographic analysis, which were obtained by slow diffusion methanol into their dichloromethane solution, respectively. For 1 b, it possesses a twisted geometry due to the steric repulsion between chlorine atom and C−H bond at the bay‐region (Figure 2 a and c), and the dihedral angle is 23.68°. In contrast to 1 b, 1 k displays centrosymmetry with a nearly planar structure (Figure 2 b), with a torsional angle of 0.76° and 2.53°. Furthermore, for 1 k, all the benzene rings are aromatic, whereas the six‐membered ring containing boron atom shows distinct antiaromatic character, in stark contrast to its pristine carbon counterpart, which possesses the aromatic feature (Figure S79). [11] The bond lengths of C1‐B1 (1.534(9) Å), C2‐B1 (1.550(5) Å), C3‐B1 (1.578(1) Å) in 1 b and C1‐B1 (1.537(4)–1.547(5) Å), C2‐B1(1.539(5)–1.549(4) Å), C3‐B1(1.567(4)–1.583(4) Å) in 1 k are comparable with the reported B‐PAHs,[ 7a , 7c , 7d , 7e , 7f ] but slightly shorter than the typical C−B bonds in unconstrained triarylboranes (1.57–1.59 Å).[ 7c , 12 ] In addition, the asymmetric unit of 1 b in the solid‐state accommodates two molecules, which form π‐stacked dimers with the shortest distance of 3.37 Å (Figure 2 c). [13] The packing diagram of 1 k exhibits an orthogonal stacking mode, where the distance of two parallel planes ranges from 3.32 to 3.40 Å (Figure 2 d). [14]

X‐ray crystallographic molecular structures of 1 b (a) and 1 k (b), and packing structures of 1 b (c) and 1 k (d). H atoms, mesityl, and tert‐butyl groups are omitted for clarity). C black, B green‐yellow, Cl red. CCDC numbers are given in the Supporting Information.

The UV/Vis absorption and fluorescence of all B‐PAHs 1 b–1 o were recorded in anhydrous dichloromethane solution (CH2Cl2) (Figure 3). For compounds 1 b–1 h, the longest‐wavelength absorption peaks range from 397 (1 h) to 443 nm (1 g) (Figure 3 a, Table S1). The maximum absorption peaks are located in the visible region from 465 (1 m) to 515 nm (1 l) for dual B‐PAHs (Figure 3 c), which are apparently red‐shifted owing to the extended π‐conjugation. Those values of maximum absorption peaks are comparable with the previous reported B‐PAHs.[ 7e , 13 ] The optical energy gaps for 1 b–1 o range from 2.30 eV (1 l) to 3.0 eV (1 h), which are estimated from the onsets of the lowest‐energy absorption band of their UV/Vis absorption spectra. Fluorescence spectroscopy shows that the emission band maxima for 1 b–1 o falls in the range between 418 (1 h) and 568 nm (1 l) (Figure 3 b and d). Similarly, the emission energies also show a redshift upon increasing the conjugation length of the compounds from mono‐B to dual‐B doped PAHs. Upon excitation, compounds 1 b–1 o exhibit fluorescence in CH2Cl2 solution with PL quantum yields (Φ PL) up to 97 % (1 g) (quinine sulfate salt as the reference for 1 b–1 e and 1 h, fluorescein acid as the reference for 1 g and 1 l–1 o, Table S1), which is higher than those of the reported cases.[ 7c , 7e , 7f ] In addition, Φ PL values of up to 91 % (1 f) are observed in their solid‐state thin films. The electrochemical properties of 1 b–1 o were then investigated by cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a solution of n‐Bu4NPF6 (0.1 M) in CH2Cl2 (Figure S54). For mono‐B doped PAHs 1 b–1 h, a single, reversible reduction wave was observed at the region between −1.98 and −2.15 V vs. Fc+/0. Among them, only 1 g can be reversibly oxidized at a potential value of E 1/2=0.84 V vs. Fc+/0. [7c] For dual B‐PAHs 1 k–1 o, in addition to the two reversible/irreversible one‐electron reductions that are identified, a reversible oxidation wave is observed with a peak potential at 0.8, 0.65, 0.95, 0.62 and 0.72 V vs. Fc+/0, respectively. Accordingly, their related electrochemical energy gaps are summarized in Table S1, which are consistent with the density functional theory (DFT) calculations (Figure S55–S66).

UV/Vis absorption spectra and fluorescence spectra of 1 b–1 o (10−6 M in CH2Cl2, 298 K). a) and b) Mono‐B PAHs 1 b–1 h. c) and d) Dual‐B PAHs 1 k–1 o. e) Electroluminescence spectra and f) the plots of EQEs of 1 f and 1 k.

In order to gain insight into the electron structures and the orbitals distribution of this series of B‐PAHs, DFT calculation at the B3LYP/6‐31G(d) level was performed. For 1 b–1 o, although the HOMOs and LUMOs are distributed over the entire molecule, the p‐orbital of boron makes a significant contribution to their LUMOs (Figure S55–S66). Moreover, the anisotropy of the induced current density (ACID) and nucleus independent chemical shifts (NICS) calculations (Figure S67–S78) were conducted for 1 b–1 o, which reveals that the continuous current flow in the whole molecular backbone is blocked by the six‐membered boracycle. These calculation results indicate that the boron‐embedded six‐membered rings exhibit apparent antiaromatic character, while other benzene rings display aromatic feature.

Encouraged by the high PL quantum yield for the synthesized B‐PAHs, we further examined their applicability for OLED applications. As a proof‐of‐concept, vacuum‐deposited OLEDs based on representative compounds 1 f and 1 k were fabricated with the device configuration of ITO/N,N′‐bis(naphthalen‐1‐yl)‐N,N′‐bis(phenyl)‐2,2′‐dimethyl‐benzidine (α‐NPD; 40 nm)/4,4′,4′′‐tris(carbazol‐9‐yl)triphenylamine (TCTA; 5 nm)/x % boron compounds: m‐CBP (20 nm)/1,3,5‐tris(6‐(3‐(pyridin‐3‐yl)phenyl)pyridin‐2‐yl)benzene (Tm3PyP26PyB; 50 nm)/LiF (1 nm)/Al (150 nm), in which the emissive layer was formed by co‐evaporating 11 v/v % of the respective B‐PAHs and m‐CBP simultaneously. The key parameters for the fabricated devices are summarized in Table S3. In good agreement with the PL studies, the electroluminescence (EL) spectra of 1 f and 1 k are found to resemble their PL in solid‐state thin films. Figure 3 e and f depict the normalized EL spectra and plots of EQEs as a function of the current density of the vacuum‐deposited devices. As shown in Table S4, blue‐ and green‐OLEDs made with 1 f and 1 k exhibit emission peaking at 456 and 516 nm, respectively, corresponding to the Commission Internationale d'Eclairage (CIE) coordinates of (0.14, 0.11) and (0.30, 0.62). With the extended π‐conjugation, the emission maximum of the device based on 1 k is found to show a bathochromic shift of 60 nm compared to that of 1 f. The maximum current efficiency of 2.3 cd A−1 and 10.7 cd A−1 are achieved for the devices based on 1 f and 1 k, respectively, which correspond to a maximum EQE of 3.5 % and 3.2 %.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated a novel one‐pot synthetic strategy for the synthesis of a new family of mono‐ and dual‐ B‐doped PAHs, from the readily available alkyne precursors. An unprecedented 1,4‐boron migration mechanism is proposed based on the controlled experiments and theoretical calculations, which is critical for the formation of the desired B‐PAHs. Our methodology reported herein is particularly attractive since it not only allows the synthesis of a broad range of B‐PAHs with various skeleton and substituents but also enables fine‐tuning of their optoelectronic properties. This established synthetic strategy thus provides a new pathway for the development of novel B‐doped PAHs and expanded graphene nanostructures, which can be promising materials for organic carbon‐based opto‐electronics.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (GrapheneCore3 No. 881603, Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant No 813036) ERC T2DCP, the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Cluster of Excellence “Center for Advancing Electronics Dresden (cfaed)” and DFG‐NSFC Joint Sino‐German Research Project (EnhanceNano), as well as the DFG‐SNSF Joint Switzerland‐German Research Project (EnhanceTopo). We thank the Center for Information Services and High Performance Computing (ZIH) at TU Dresden for generous allocations of compute resources. We thank Dr. Siu‐Lun Lai and Dr. Mei‐Yee Chan (The University of Hong Kong) for assistance in fabricating the OLED devices. J. Liu is grateful for the startup funding from The University of Hong Kong and the funding support from ITC to the SKL. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

1

1a

1d

1e

1h

2

3

3a

3b

5

5d

5d

5e

5e

6

6a

6d

6f

6f

6g

6h

6i

7

7a

7a

7b

7b

7c

7c

7d

7d

7e

7f

7g

8

8a

9

9a

9b

9b

10

11

12

13

14

One‐Pot Synthesis of Boron‐Doped Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons via 1,4‐Boron Migration

One‐Pot Synthesis of Boron‐Doped Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons via 1,4‐Boron Migration

![Typical synthetic routes to B‐doped PAHs. a) A Si/B exchange method;

[7c]

b) Borylative cyclization combining electrophilic C−H borylation method;

[7e]

c) Electrophilic C−H borylation method from arylalkenes;

[7f]

d) One‐pot synthetic method demonstrated in this work.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765941297697-e770f974-f2b9-4c2c-b606-c251b7b27845/assets/ANIE-60-2833-g001.jpg)