- Altmetric

RNA detection permits early diagnosis of several infectious diseases and cancers, which prevent propagation of diseases and improve treatment efficacy. However, standard technique for RNA detection such as reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction has complicated procedure and requires well-trained personnel and specialized lab equipment. These shortcomings limit the application for point-of-care analysis which is critical for rapid and effective disease management. The multicomponent nucleic acid enzymes (MNAzymes) are one of the promising biosensors for simple, isothermal and enzyme-free RNA detection. Herein, we demonstrate simple yet effective strategies that significantly enhance analytical performance of MNAzymes. The addition of the cationic copolymer and structural modification of MNAzyme significantly enhanced selectivity and activity of MNAzymes by 250 fold and 2,700 fold, respectively. The highly simplified RNA detection system achieved a detection limit of 73 fM target concentration without additional amplification. The robustness of MNAzyme in the presence of non-target RNA was also improved. Our finding opens up a route toward the development of an alternative rapid, sensitive, isothermal, and protein-free RNA diagnostic tool, which expected to be of great clinical significance.

•

Isothermal, rapid, robust, and sensitive RNA detection platform was developed.

•Polycation-chaperoned LNA-modified MNAzymes enables one-step RNA detection.

•Structural modification and the copolymer enhanced MNAzyme activity by 2,700 fold.

•Detection limit of femtomolar was achieved without additional amplification step.

Introduction

The outbreak of infectious diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), poses a significant risk to human health. Rapid and accurate identification of pathogenic viruses plays a crucial role in the early diagnosis and outbreak management (Batule et al., 2020; Hu et al., 2017; Jung et al., 2016; Tram et al., 2020). With the advance in molecular biology, RNA detection methods have been developed rapidly and become a gold standard for detection of disease biomarkers (Ding et al., 2018; Mahony, 2010). Therefore, rapid, simple and customizable RNA detection method is highly desirable for routine diagnostic of emerging diseases and preparation for the future pandemics.

The methods based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) have been regarded as the gold standard for nucleic acid detection. However, PCR-based methods are generally time-consuming, have complicated procedures, and require well-trained personal and costly equipment (Shen et al., 2015; van Elden et al., 2004). Moreover, reverse-transcription of RNA target is required before amplification by PCR. The interconnection of multiple steps are more likely to cause contamination, and each step needs to be optimized (Ye et al., 2019). The more recent isothermal amplification methods have a greatly improved detection performance without thermocycler (Table S2). Nevertheless, these methods still have tedious experimental steps, require several protein enzymes and complicated probe design.

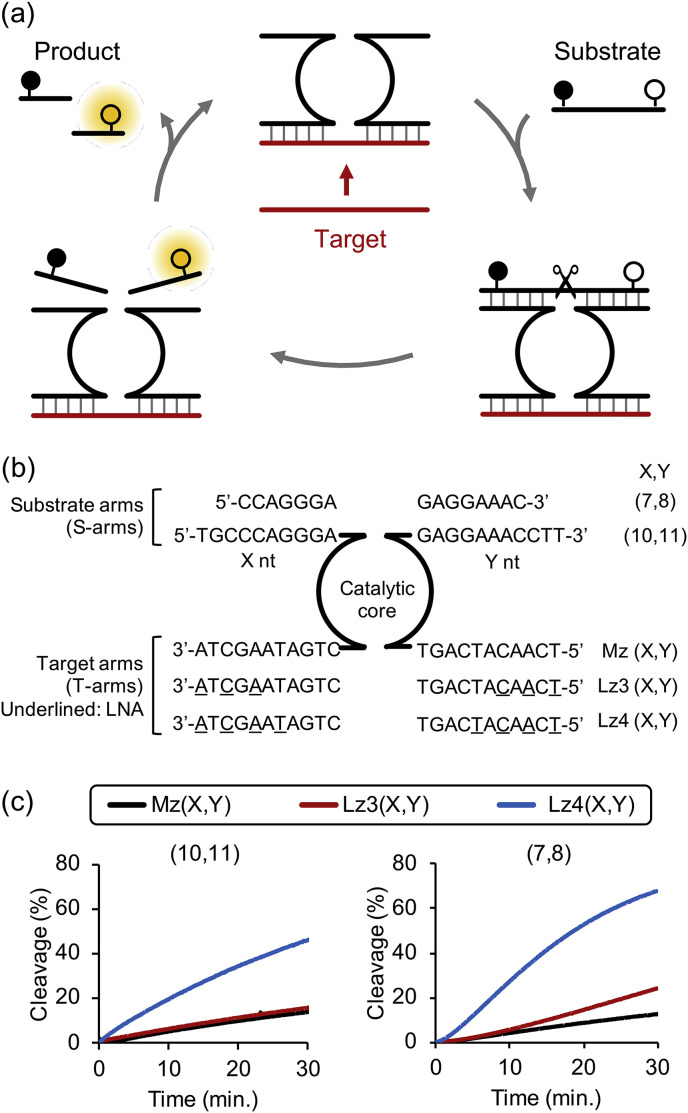

An alternative method for RNA analysis may include DNAzyme assay. The 10–23 DNAzyme is catalytically active DNA molecule that cleave complementary RNA substrates. It has a conserved catalytic core region flanked by two variable substrate arms (S-arms). Multi-component nucleic acid enzymes (MNAzymes) derived from 10-23 DNAzyme consist of two partzymes, each containing S-arm, half of the catalytic core, and target arm (T-arm). The presence of specific target directs assembly of the partzymes into a catalytically active MNAzyme. Signal associated with cleavage of substrates functionalized with a dye and a quencher (Fig. 1 a). Many nucleic acid detection methods suffer from complicated primer and probe design. In contrast, T-arms of MNAzymes are easily tailored to detect any DNA and RNA sequences without reverse transcription step, making them a promising tool for nucleic acids detection (Hanpanich et al., 2019; Mokany et al., 2010; Safdar et al., 2020).

(a) Schematic of MNAzyme cleavage reaction. (b) Sequences and code name of MNAzymes indicating S-arms length and number of LNA in T-arms. (c) Cleavage of substrate by MNAzyme and LMNAzyme with long S-arms (10,11) and truncated S-arms (7,8). Experiments were repeated three times and representative cleavage kinetics of each condition were shown. Average kobs and standard deviation of three replicates were shown in Fig. S2. Reactions contained 20 nM MNAzymes, 100 nM substrate and 20 nM miR-21 and conducted at optimal temperature of each MNAzyme.

The selectivity and stability of nucleic acids assembly influence cleavage efficiency of DNAzymes (Santoro and Joyce, 1998). Modification of the S-arms of DNAzymes with locked nucleic acids (LNA) improves substrate hybridization as the LNA residues have high binding affinity for complementary DNA and RNA (Braasch and Corey, 2001; Kaur et al., 2007; Koshkin et al., 1998; Obika et al., 1998; Petersen and Wengel, 2003) and yields DNAzymes with enhanced cleavage activity relative to unmodified versions (Donini et al., 2007; Kaur et al., 2010; Schubert et al., 2003; Vester et al., 2002). We reported that the addition of cationic comb-type copolymer, poly(L-lysine)-graft-dextran (PLL-g-Dex), promotes nucleic acids assembly and enhances thermal stability of duplex and triplex nucleic acids (Maruyama et al., 1999, 1998, 1997; Hanpanich and Maruyama, 2020). The copolymer also significantly enhances activity and stability of DNAzymes (Gao et al., 2015a; Hanpanich et al., 2020) and MNAzymes (Gao et al., 2015b; Hanpanich et al., 2019; Rudeejaroonrung et al., 2020).

In this study, we report one-step RNA detection using a simple design MNAzymes with remarkably improved analytical efficiency. For the first time, we introduced LNA into T-arms of MNAzymes (Fig. 1b), hereafter termed LMNAzymes, to increase affinity for RNA target, while LNA modifications had been previously restricted to the S-arms of DNAzymes. We demonstrated rational combination of LNA modification, S-arm truncation and the addition of copolymer which synergistically enhanced MNAzymes activity and selectivity greater than the sum of the effect from each strategy. MNAzyme-based assay generally couples with complicated signal amplification strategies to enhance analytical performance (Li et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016). In contrast, our strategy permits sensitive, one-pot RNA detection without labor-intensive steps.

Experimental section

Materials

Poly(L-lysine hydrobromide) (Mw = 7.5 × 103) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). Dextran (Mn = 8.0 × 103–1.2 × 104) was purchased from Funakoshi Co. (Japan). Sodium hydroxide, sodium chloride, and manganese (II) chloride tetrahydrate were purchased from Wako Pure Chemical Industries (Japan). 2-[4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazin-1-yl]ethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) was obtained from Nacalai Tesque, Inc. (Japan). HeLa cell total RNA was purchased from Takara (Japan). Unmodified oligonucleotides used in this study were purchased from Fasmac Co., Ltd (Japan). Oligonucleotides with LNA modification were purchased from GeneDesign, Inc. (Japan). All oligonucleotides were HPLC-grade and were used without further purification. Oligonucleotide sequences are shown in Table S1.

Synthesis of poly(L-lysine)-graft-dextran

PLL-g-Dex was prepared according to the previously published protocol (Maruyama et al., 1997). Briefly, PLL-g-Dex consisting of 10 wt% PLL and 90 wt% dextran (11.5 mol% of lysine units of PLL were substituted with dextran) was obtained by reductive amination reaction of dextran with PLL. The polymers were purified by ion-exchange, dialyzed, and freeze-dried. The products were then characterized by 1H NMR (Bruker Avance 400, USA) at 60 °C and by GPC (Jasco, Japan).

MNAzyme reaction analysis

The MNAzyme reactions were analyzed by Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET). We prepared 2 mL reaction solutions (final concentration in brackets). Unless otherwise indicated, we dissolved substrate (100 nM), each partzyme (20 nM) and miR-21 (20 nM) in 850 μL milliQ and added 1 mL reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.3). The reaction mixtures were pre-incubated with a stirrer at the indicated reaction temperature in a spectrofluorometer machine. After 5 minutes of pre-incubation, either 50 μL of milliQ or PLL-g-Dex solution dissolved in milliQ was injected into the reaction mixtures. In the presence of the copolymer, the molar ratio of amino groups of the copolymer to phosphate groups of nucleotides (N/P) in the final solution was 2. After another 90 seconds of incubation, 100 μL of MnCl2 solution was injected (final concentration of 5 mM). The substrate was labeled with FITC and BHQ-1 such that cleavage could be monitored as increases fluorescence signal due to separation of this fluorophore-quencher pair (Ex: 494 nm; Em: 520 nm). An increased fluorescence over time was measured using an FP-6500 spectrofluorometer (Jasco, Japan). The percent substrate cleavage was obtained from the following equation:

MNAzyme reaction in real sample

MNAzyme activity was analyzed in the presence of total RNA extracted from HeLa cells (total RNA). The reaction mixtures contained 100 nM substrate, 20 nM partzymes, and 1 nM synthetic miR-21 were mixed with total RNA at final concentration 5 μg/mL in total reaction volume of 2 mL and pre-incubated in reaction buffer for 5 minutes at optimal temperature (50 °C for long S-arms and 37 °C for short S-arms). The copolymer and MnCl2 were added to the reaction mixtures and MNAzyme reactions were analyzed as described in section 2.3.

Results and discussion

A model target of this study is microRNA-21 (miR-21) which is upregulated in many types of cancers and related to cardiovascular diseases (Kumarswamy et al., 2011; Si et al., 2007). MicroRNAs are well-known biomarkers for clinical diagnosis of several diseases (Lu et al., 2005; Rupaimoole and Slack, 2017; Zare et al., 2018). An altered expression of several microRNAs is also associated with infections caused by respiratory viruses, such as coronavirus, rhinovirus, and influenza virus (Leon-Icaza et al., 2019).

Effect of LNA modification on the MNAzymes activity

Introduction of LNA into T-arms led to an enhancement of substrate cleavage (Fig. 1c). The k obs for the LNA-modified Lz4(10,11), which has four LNA residues, in the presence of miR-21 target was higher by 4 fold compared to that of unmodified Mz(10,11) (Table 1 ). We speculate that LNA modifications increased the activity by promoting the formation of an active MNAzyme complex. The activity was further improved by S-arm truncation (Fig. 1c and Table 1): The k obs of the LMNAzyme Lz4(7,8) was 2-fold higher than of Lz4(10,11). The S-arm truncation probably promoted product release and increased substrate turnover. Noted that the activity was not improved by S-arm truncation without LNA modification, likely because target binding is the rate-limited step.

| Copolymer | Substrate arms (10,11)b | Substrate arms (7,8)b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kobs (min−1) | S/Bc | kobs (min−1) | S/Bc | ||||

| 20 nM miR-21 | 0 nM miR-21 | 20 nM miR-21 | 0 nM miR-21 | ||||

| – | Mz | 4.28 × 10−3 (1) | 1.55 × 10−4 (1) | 27.61 (1) | 3.91 × 10−3 (1) | 6.05 × 10−5 (1) | 64.6 (1) |

| Lz3 | 5.42 × 10−3 (1.3) | 1.10 × 10−4 (0.71) | 49.3 (1.8) | 1.18 × 10−2 (3.0) | 2.12 × 10−5 (0.35) | 557 (8.6) | |

| Lz4 | 1.74 × 10−2 (4.1) | 4.22 × 10−5 (0.27) | 412 (15) | 2.96 × 10−2 (7.6) | 6.07 × 10−5 (1.0) | 488 (7.5) | |

| + | Mz | 5.41 × 10−1 (1.3 × 102) | 6.66 × 10−3 (43) | 81.2 (2.9) | 2.03 (5.2 × 102) | 7.08 × 10−4 (12) | 2.87 × 103 (44) |

| Lz3 | 5.21 (1.2 × 103) | 8.94 × 10−4 (5.8) | 5.83 × 103 (2.1 × 102) | 9.85 (2.5 × 103) | 9.66 × 10−4 (16.0) | 1.02 × 104 (1.6 × 102) | |

| Lz4 | 6.19 (1.4 × 103) | 8.74 × 10−4 (5.6) | 7.08 × 103 (2.6 × 102) | 11.6 (3.0 × 103) | 1.66 × 10−3 (27.4) | 6.99 × 103 (1.1 × 102) | |

a The average kobs values of three repeated experiments were shown. The plot with error bars is shown in Fig. S2. Reactions were performed with 100 nM substrate, 20 nM each partzyme, and 0 or 20 nM miR-21 at the optimal temperature for each condition.

b The numbers in parentheses indicate ratio relative to the first value of each column.

c S/B is the ratio of kobs in the presence of 20 nM miR-21 to that in the absence of miR-21.

MNAzyme activity could be impeded by an insufficient substrate association when S-arms are short. Although incorporation of LNA into S-arms enhances substrate binding (Donini et al., 2007; Schubert et al., 2003; Vester et al., 2002), an excess of LNA modifications could be detrimental due to a decrease in a product dissociation rate (Schubert et al., 2003). Therefore, a rational combination of different strategies is required to achieve the optimal association and dissociation kinetics for each element of MNAzyme.

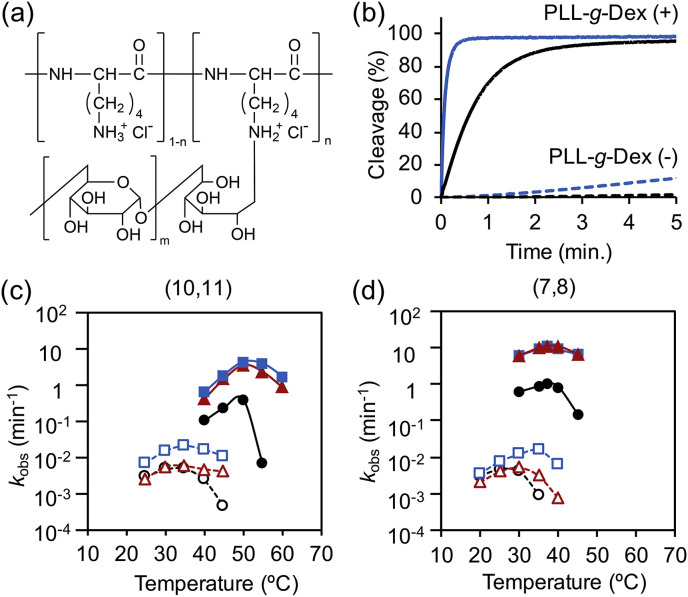

Effect of MNAzyme structural modification and cationic copolymer

We avoided LNA modifications of S-arms and added PLL-g-Dex (Fig. 2 a) to improves substrate association since the copolymer stabilizes nucleic acid duplexes by increasing the association rate rather than by decreasing the dissociation rate (Maruyama et al., 1999; Torigoe et al., 1999). The addition of the copolymer significantly enhanced the activity of MNAzymes. For example, the activity of Mz(7,8) was enhanced by 2 orders of magnitude compared to the condition without the copolymer (Fig. 2b and Table 1). LNA modification of the T-arms further increased the activity of Lz4(7,8) with more than 5-fold improvement relative to Mz(7,8) (Fig. 2b and Table 1). The combination of two stabilizing methods cooperatively enhanced target affinity as the copolymer increases the association rate and LNA modifications decrease the dissociation rate (Torigoe et al., 2009). We previously reported the synergistic stabilization by the copolymer and N3’→P5’ phosphoramidate modification (Torigoe and Maruyama, 2005). Hence, MNAzyme activity should be also enhanced by other modifications cooperatively with the copolymer. Furthermore, S-arms truncation also increased activity as product dissociation was promoted. As a result, the combination of LNA modification, S-arms truncation and the copolymer enhanced the activity of Lz4(7,8) by 2,700 fold compare to that of Mz(10,11) without the copolymer (Table 1).

(a) Chemical structure PLL-g-Dex. (b) Effect of copolymer and LNA modification on substrate cleavage activity. Black and blue lines represent the activities of Mz(7,8) and Lz4(7,8), respectively. Representative cleavage kinetics of each condition were shown. (c, d) Temperature dependence of MNAzymes and LMNAzymes with (c) long and (d) short S-arms. Black lines (circle), red line (triangle), and blue line (square) are data for Mz(X,Y), Lz3(X,Y), and Lz4(X,Y), respectively. Dashed lines (open symbols) and solid lines (filled symbols) indicate reactions without and with copolymer, respectively. Reactions contained 100 nM substrate, 20 nM partzyme, and 20 nM miR-21. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Many isothermal amplification methods require additional primer annealing step and heat inactivation of protein enzymes which make the detection still complicate (Table S2). Some methods also required high temperatures for effective amplification such as 63 °C for loop-mediated isothermal amplification (Teoh et al., 2013). In contrast, MNAzymes permits isothermal and protein-free RNA detection under simple conditions. Temperature dependence of MNAzyme activity demonstrated that the optimal temperature can be simply tuned by adjusting S-arms length without compromising the catalytic efficacy. In the presence of PLL-g-Dex, truncation of S-arms by three nucleotides reduced optimal temperature from 50 to 37 °C (Fig. 2 c, d; Fig. S1). The optimal temperature of MNAzyme could be further decreased to 25 °C without activity loss (Hanpanich et al., 2019), which is desirable for on-site detection with resource-limited settings.

In addition to the enhanced activity and tunable working temperature, LMNAzyme was also effective in a wider temperature window than the MNAzyme without the LNA modification (Fig. 2c and d). In the absence of copolymer, the activity of Mz(10,11) dropped significantly above 35 °C, whereas Lz3(10,11), which has three LNA modifications, and Lz4(10,11), with four LNA modifications, were active from 25 °C to 45 °C (Fig. 2c). In the presence of copolymer, a sharp drop in k obs was observed above 50 °C for the Mz(10,11), but Lz3(10,11) and Lz4(10,11) remained active at 60 °C (Fig. 2c). Similar trends were observed for short S-arms constructs (Fig. 2d). As the thermostability of nucleic acid duplexes increases when LNA monomers are incorporated (Singh et al., 1998), the wider working temperature window and cleavage efficiency of the LMNAzymes are likely due to increased thermal stability of partzyme-target duplexes.

There was less target-independent cleavage (background reaction in the absence of target) by LMNAzyme (Table 1). Despite a significant enhancement of signal by the copolymer, background level was considerably higher. For example, background k obs of Mz(10,11) in the absence of the copolymer was 1.55 × 10−4 min−1, whereas that in the presence of the copolymer was 6.66 × 10−3 min−1 (Table 1). Thus, the S/B of Mz(10,11) in the presence of the copolymer was limited at 81.2 (Table 1). Interestingly, LNA modification not only enhanced signal but also considerably reduced background of LMNAzyme compared to the unmodified MNAzyme counterpart. The S/B of Lz4(10,11) was increased to 7.08 × 103 by the addition of the copolymer combined with LNA modifications (Table 1). Background was also minimized by S-arm truncation as the partzyme-substrate complex formation is decreased (Hanpanich et al., 2019). In contrast, background reduction by the LNA modification likely due to conformational differences between the modified and unmodified MNAzymes since the sugar conformations of single-stranded DNA containing some LNA residues and DNA are different (Petersen et al., 2000). We speculate that the conformation of partzymes that contain LNA residues are unfavorable for the catalytic core folding, resulting in little target-independent cleavage.

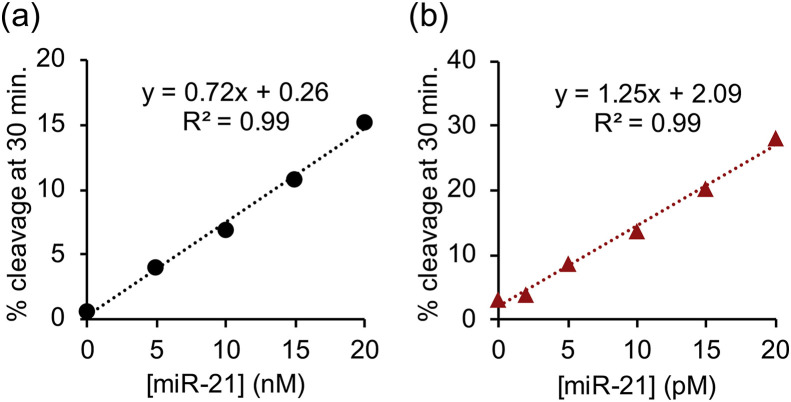

Analytical performance

Analysis of target concentration dependence confirmed that the LNA modification combined with S-arm truncation and the addition of copolymer significantly improved target affinity (Figs. 3 and S3). After 30 minutes, the unmodified MNAzyme Mz(10,11) without copolymer cleaved 15% of substrate in the presence of 20 nM miR-21 (Fig. 3 a), whereas Lz3(7,8) in the presence of copolymer cleaved 30% of substrate in the presence of 1000 times lower target concentration (Fig. 3b). These results indicate that our combined strategies enhance both reactivity and selectivity of MNAzymes. The limit of detection (LOD) of individual experiment was estimated based on the equation, LOD = 3 × (σ/s), where σ is the standard deviation of y-intercept and s is the slope of a calibration curve (Nata, 2012; Rajaković et al., 2012; Şengül, 2016). The LOD of Lz3(7,8) in the presence of the copolymer is 73 fM. The sensitivity was comparable to RNA detection by quantitative real-time PCR (Kilic et al., 2018) and other isothermal amplification methods (Table S2). It is important to note that the analytical performance of MNAzyme was significantly enhanced even without additional signal amplification procedures.

Dependence of percent substrate cleavage at 30 minutes on miR-21 concentration of (a) Mz(10,11) in the absence of PLL-g-Dex and (b) Lz3(7,8) in the presence of PLL-g-Dex. The concentration of substrate and each partzyme were 100 nM and 20 nM respectively. Reactions were performed under optimal temperature of each MNAzyme at various miR-21 concentrations as indicated.

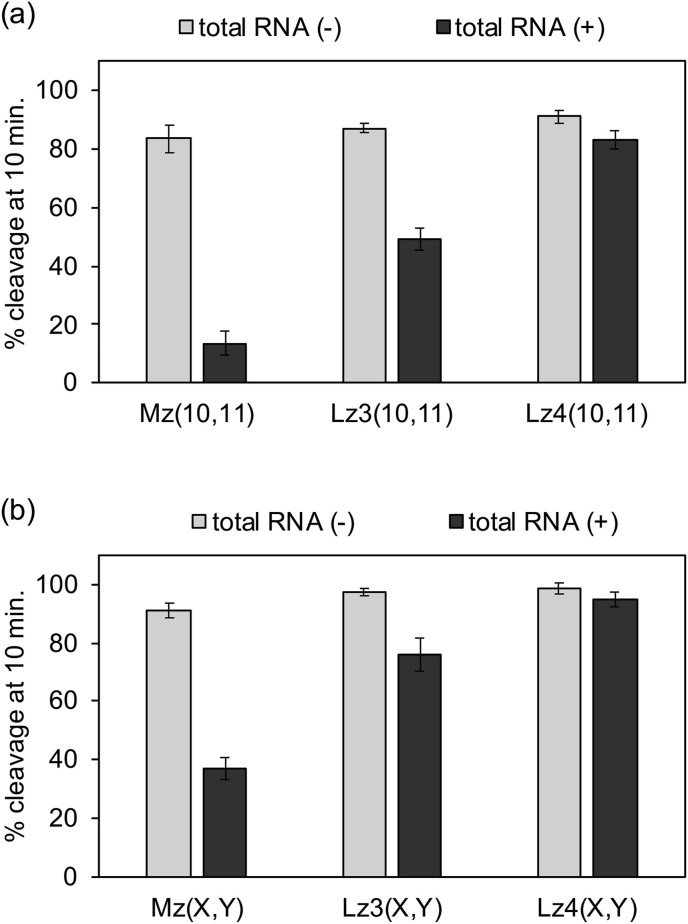

Moreover, cleavage activity was evaluated in the presence of HeLa cell total RNA. Without HeLa cell RNA, 80–95% of the substrate was cleaved after 10 minutes (Fig. 4 ). In the presence of HeLa cell RNA, the activity of the unmodified MNAzymes was dramatically decreased. Less than 10% of substrate was cleaved by Mz(10,11) after 10 minutes (Fig. 4a), and only 20% of substrate was cleaved by Mz(7,8) within the same period of time (Fig. 4b). The HeLa cell RNA likely interfered with folding of the catalytic core and/or competitively bind to the target site. Sample purification might improve MNAzyme activity but this addition process could complicate the detection procedure. Interestingly, the activity of the LNA-modified MNAzymes were retained in the presence of HeLa cell RNA. Cleavage efficiency of Lz4(10,11) with four LNA residues in the T-arms was comparable in the presence and absence of HeLa cell RNA (Fig. 4a). Activity was also similar with and without HeLa cell RNA for the LNA-modified MNAzyme with short S-arms (Fig. 4b). Due to an enhanced target affinity by LNA modification, LMNAzymes maintain their catalytic efficiency in the presence of non-target RNA, enabling target detection without sample purification.

Effect of total RNA from HeLa cells on the activity of MNAzymes with (a) long S-arms and (b) short S-arms. Reaction solutions contained 100 nM substrate, 20 nM partzymes, 1 nM miR-21, without or with HeLa cell total RNA at concentration 5 μg/mL in total reaction volume of 2 mL. MNAzyme assay were conducted in the presence of copolymer at optimal temperature. Experiments were repeated three times.

Conclusion

In summary, MNAzyme activity and selectivity were enhanced by a combination of LNA modification, S-arm truncation, and addition of the copolymer. Sub-picomolar detection limits was achieved in one step of measurement. Our simple yet effective strategies will allow broader application of a highly simplified MNAzyme-based diagnostic tools. Compared with other isothermal amplification methods, our LMNAzyme-based method has comparable sensitivity and offers several advantages (Table S2). Since reverse transcription and additional amplification step are not required, the measurement can be done in one pot with time-to-results less than 1 hour. Simple and enzyme-free reaction is easy to operate without high technical skills and sophisticate instrument. The development of practical LMNAzyme diagnostic platform could potentially aid point-of-care RNA detection and disease monitoring, as they are low cost (around $3 USD per sample) and easy to operate.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Orakan Hanpanich: Investigation, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Ken Saito: Investigation. Naohiko Shimada: Supervision. Atsushi Maruyama: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by Center of Innovation (COI) Program (JPMJCE1305),

One-step isothermal RNA detection with LNA-modified MNAzymes chaperoned by cationic copolymer

One-step isothermal RNA detection with LNA-modified MNAzymes chaperoned by cationic copolymer