- Altmetric

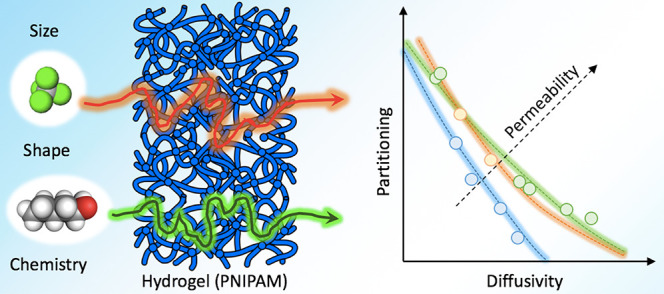

The permeability of hydrogels for the selective transport of molecular penetrants (drugs, toxins, reactants, etc.) is a central property in the design of soft functional materials, for instance in biomedical, pharmaceutical, and nanocatalysis applications. However, the permeation of dense and hydrated polymer membranes is a complex multifaceted molecular-level phenomenon, and our understanding of the underlying physicochemical principles is still very limited. Here, we uncover the molecular principles of permeability and selectivity in hydrogel permeation. We combine the solution–diffusion model for permeability with comprehensive atomistic simulations of molecules of various shapes and polarities in a responsive hydrogel in different hydration states. We find in particular that dense collapsed states are extremely selective, owing to a delicate balance between the partitioning and diffusivity of the penetrants. These properties are sensitively tuned by the penetrant size, shape, and chemistry, leading to vast cancellation effects, which nontrivially contribute to the permeability. The gained insights enable us to formulate semiempirical rules to quantify and extrapolate the permeability categorized by classes of molecules. They can be used as approximate guiding (“rule-of-thumb”) principles to optimize penetrant or membrane physicochemical properties for a desired permeability and membrane functionality.

In the past decade, we witnessed considerable research progress in hydrogels and their applications, owing to the advances in materials science, nanotechnology, polymer physics, and fabrication techniques.1−3 Hydrogels are cross-linked polymer networks containing a considerable amount of water. How much water a hydrogel contains depends on its chemistry, the density of cross-linkers, and environmental parameters, such as temperature. The attention has in recent years shifted toward stimuli-responsive hydrogels, popularly known as “smart” or “active” materials, which undergo a rapid and reversible structural transformation in response to an environmental stimulus (e.g., temperature or pressure).2,4,5 They have become building blocks in a broad repertoire of biomedical, pharmaceutical, and other applications, including chemical separation,6 biosensors,7 nanofiltration,8,9 active interfaces,10 biomedical devices,11,12 nanocatalysis,13−16 and—maybe the most eminent example—controlled drug delivery.3,17,18 In the latter, hydrogels can be designed to selectively encapsulate and release particular types of pharmaceuticals in a controllable way. Related aspects are used in “programmable” nanoreactors, where catalytic nanoparticles are confined in a permeable hydrogel that shelters and controls the catalytic process.13,14,19−22 Most of these applications exploit a tunable permeation of small target molecules (referred to as penetrants) through a responsive hydrogel. Permeation is driven by a chemical potential gradient of penetrants, caused for instance by a concentration difference Δc on both sides of the hydrogel. In this case, the permeation flux density is given as j = P(Δc/L), where L is the thickness of the hydrogel and P stands for permeability, which will be the central quantity of discussion in this work. Permeability defined in this way is an intensive quantity with units of a diffusion coefficient; however, the definitions vary among different fields. Based on the well-established solution–diffusion theory,23,23−25 the permeability can be written as the product of the diffusion coefficient (diffusivity) D of the penetrant and its partition ratio (partitioning) in the material K, as

There were several attempts to devise heuristic rules for permeability based on experimental observations and subsidized by phenomenological theories.31,32 The research on penetrant transport has a venerable history, resulting in a plethora of theories based on different premises.33,34 Although many of them have been successful in rationalizing the diffusivities of several penetrants, most have shortcomings, as they either are not really atomistic or assume a certain molecular behavior in an ad hoc manner.35 The problem is that permeation is a complex multiscale phenomenon; thus picking the right theory is a formidable challenge.36 For instance, the role played by the shape and the “chemistry” (i.e., hydrogen bonds, polarity, charges) of penetrating molecules is still not understood. A suitable method that can assist in a theoretical understanding is molecular simulations, but which are nowadays unfortunately still limited in this field because of the computationally intensive nature needed for studying permeability.

In this work, we elucidate the role of the penetrant’s shape and polarity in the permeability as resolved from comprehensive molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of a poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) hydrogel. PNIPAM is the most prominent and most studied thermoresponsive polymer, owing to its biocompatibility and the volume transition temperature (VTT) close to human body temperature, and it serves as the prototypical model system for many studies today.37 We combine the simulation data from this work with the data from our recent studies.38−41 We separately analyze the partitioning and diffusivity of different penetrants in swollen and collapsed states of PNIPAM, which enables us to evaluate the permeability based on the solution–diffusion model. To understand the background of the permeability in the collapsed state, we rationalize each of the two components of the permeability—the diffusivity and the patitioning—by semiempirical scaling relations.

Results and Discussion

Modeling Approach

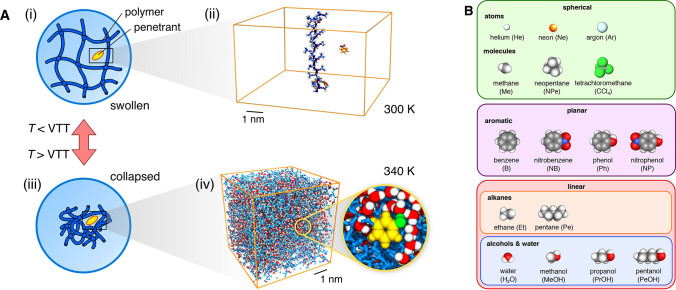

PNIPAM-based hydrogels undergo a volume transition (i.e., a transition between the swollen and collapsed state) at the VTT of around 305 K (32 °C).37 In order to treat the two states with computer simulations, we use two distinct models established before, which are suitable for hydrogels with low cross-linker concentrations,38,39 as shown in Figure 1A. The model for the swollen state is a single stretched and periodically replicated polymer chain in a box of water at 300 K (below the VTT); see Figure 1A(i, ii). This chain can be considered as a segment of a swollen polymer network, where neighboring chains are far apart and do not interfere with each other, feasible for low cross-linker concentrations. The model for the collapsed state (Figure 1A(iii, iv)) consists of aggregated polymeric chains (20 monomer units long) at 340 K (above the VTT).39 Because the model does not have cross-linkers, it is suitable for a collapsed hydrogel with very low (few percents) cross-linker concentrations, in which the cross-linkers do not pose major geometrical constraints during the collapse. We examine the permeability of various penetrant molecules in PNIPAM hydrogels, with the focus on the collapsed state. We first briefly tackle the swollen state—for which the results can be easily interpreted—and then, for the rest of the article, concentrate on the collapsed state, which yields much more complex permeability behavior.

(A) Atomistic modeling of PNIPAM hydrogels with penetrants. Top: (i) a swollen network, where adjacent chains are far apart (relevant for temperatures below the VTT), is simulated as (ii) an infinitely long chain to study adsorption38 (water not shown for clarity). Bottom: (iii) a collapsed hydrogel (relevant for temperatures above the VTT) is modeled as (iv) a dense aggregate of PNIPAM polymers containing penetrants (an example of phenol is shown in yellow).39,40 (B) Penetrant molecules in our study classified into three groups based on shape.

We explore the behavior of different kinds of penetrants, which we categorize into three groups based on their shape and chemistry, as shown in Figure 1B. The first group consists of spherical penetrants, featured by equal lengths of their principal axes. The second group includes planar (aromatic) molecules, with one principal axis shorter than the other two. Here, nitrobenzene and nitrophenol are particularly popular in model reactions in nanocatalysis,42,43 used also in connection with PNIPAM hydrogels.14 Finally, the third group constitutes linear (rod-like) molecules, such as alkanes and alcohols, with one axis longer than the other two. For simplicity, we also place the water molecule into the latter group.

The simulation data for the analysis are partially taken from our previous studies38−40 and partially supplemented by simulations in this work (see the Methods section for details).

Swollen State

The single-chain model of a swollen state (Figure 1A(ii)) enabled us to study the adsorption of molecules onto the polymer.38 In the linear regime of adsorption, valid for concentrations of molecules up to around c0 ≈ 10 mM,38 the number of adsorbed molecules per monomer is Nads = Γm*c0, where Γm* is referred to as an adsorption coefficient. We can then predict the partitioning in a hypothetical swollen gel (denoted by the subscript “s”) as38,41

This single-chain model does not lend itself to study diffusion in a swollen network. Diffusion studies in swollen networks within the all-atom framework are very scarce, one of the reasons being that they are computationally expensive because of a huge amount of simulated water and, more importantly, that they are not expected to be particularly illuminating compared to other, more generic and cheaper coarse-grained models. We will therefore resort to theoretical predictions for rough estimations of the diffusion coefficients. Fortunately, diffusion theories are typically successful for swollen networks of low polymer volume fractions.33,34,36

We first recall that the diffusion in water is described by the Stokes–Einstein equation,45

Nonsteric effects are more challenging to incorporate into the theory. In a simplified picture, a steric network decorated by an attractive potential engenders an adsorption and trapping of the penetrant, which in turn prevents its diffusion while it is adsorbed.49 This notion leads to a simple relation, proposed and verified by coarse-grained simulations,30

The corresponding permeability in the swollen state, Ps = KsDs, is then

As simple as this model may be, it suggests that the permeability depends foremost on the polymer volume fraction and to some extent on the penetrant’s size via the excluded-volume principle. The “chemistry” of the penetrant, that is, its specific interaction with the polymer, has entered the partitioning and diffusivity in reciprocal ways and canceled out and is thus irrelevant for the permeability.

Collapsed State

We now move on to the core of this work, namely, to the collapsed state (Figure 1A(iv)). The amount of sorbed water between the aggregated chains is chosen such that it matches the chemical equilibrium of bulk water, which for the used model is around 20 wt % (somehow below experimental estimates, of around 30 wt %17,50−53). This makes the polymer volume fraction around ϕ ≈ 0.8. Water is very nonuniformly distributed throughout the phase in a form of irregular nanoscopic clusters, as is common to dense amorphous polymer structures in general.26,54,55

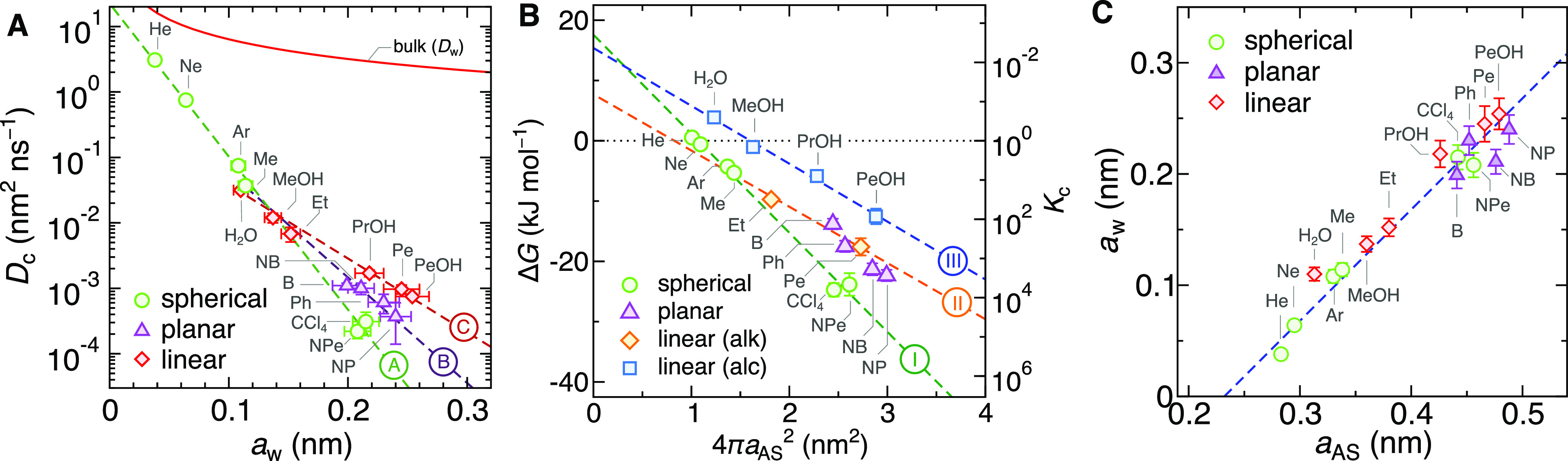

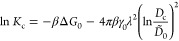

Diffusion in this packed polymer structure advances via the hopping mechanism, identified in simulations35,56−58 as well as experiments,59,60 where a penetrant performs jumps from one local cavity formed by the chains to another local cavity through short-lived water channels created by thermal fluctuations.39 This makes the diffusion a barrier-crossing phenomenon.39 In Figure 2A we plot the diffusion coefficient in the collapsed state Dc (“c” standing for collapsed) against the penetrant’s size, characterized by the Stokes radius aw (defined through eq 3 from a measured Dw of the penetrant in water). In our previous study, we already noted that diffusion coefficients in this system very roughly follow an exponential dependence,39 but now, with the extended assortment of penetrants, it is clear that the data points of larger penetrants (beyond methane) start to scatter from a single decreasing trend.

(A) Diffusion coefficients of penetrants in the collapsed PNIPAM polymer (at 340 K) versus their Stokes radii in bulk water, categorized into three groups based on their shape (see Figure 1B). The dashed lines are fits of eq 8 to the three different categories, denoted as A, B, and C (see Table 1). The red solid line is the diffusion coefficient in bulk water (Dw), given by eq 3. (B) Transfer free energies of penetrants from water into the collapsed PNIPAM (left scale) and the corresponding partition ratio (right scale) versus the accessible surface area (ASA), categorized into four groups of penetrants based on the shape and polarity. The dashed lines are fits of eq 10 to three different categories, denoted as I, II, and III; planar penetrants excluded (see Table 1). (C) Correlation diagram of awversus aAS for the simulated penetrants. The blue dashed line is the fit of eq 11 to the data points.

Notably, by classifying the penetrants (see Figure 1B) as spherical (green circles), planar (purple triangles), and linear (red diamonds), the diffusivity of each group individually follows very well an exponential dependence:

With an increasing size, the course of diffusion coefficients first follows the exponential dependence of the spherical geometry and then forks into three branches at around the size of the methane molecule, whence also nonspherical structures are realizable. Thereby, planar and even more so linear penetrants diffuse significantly faster than spherical penetrants of equal Stokes radii. The influence of shape on diffusion in dense polymers is poorly understood.36 In our case, we believe the reason lies in the hopping through transient channels, where the smallest cross section of the penetrant is the determining dimension. Namely, molecules preferably move through narrow channels in the direction of the smallest cross section. Clearly, spherical particles have the largest cross section among all three geometries for a given Stokes radius, therefore the smallest diffusion coefficient Dc in the hydrogel. On the other hand, the Stokes radius is approximately equal to the mean of all three principal axes of the penetrant;45,61 thus all cross sections contribute similarly to diffusion in water.

The polymer–penetrant interaction (the chemical type) seems not to be a prevailing factor in diffusion. The reason could be that during a hopping event the coordination of the solvation shell of a penetrant is not significantly perturbed,39 and consequently the free energy changes are much smaller than steric interactions of local trapping. An emerging important conclusion from Figure 2A is that for a given shape category the diffusion coefficients in our system decay exponentially with the penetrant’s size.

Even though some studies suggest such a diffusivity scaling in dense systems,62−64 most of them propose or assume exponential decays with a square or cube of the penetrant size.33,34 In the Supporting Information (SI) we show that these other two alternatives give significantly worse fits to our data than eq 8. Particularly the square scaling, ln Dc ∝ −aw2, is deeply rooted in the polymer community. For instance, it follows from the free-volume theory33,65,66 and serves as the basis for the well-established framework for gas separation by polymer membranes by Freeman.67

The question on diffusivity-size scaling is complex and still under debate, as it seems that it depends not only on the polymer but also on the temperature regime. Kumar, Zhang, and co-workers used coarse-grained, implicit-solvent models and identified three generic regimes of diffusion in polymers.68−70 While the diffusivity of very small penetrants indeed follows ln Dc ∝ −aw, it is not activated. For larger penetrants at temperatures above the glass transition temperature (Tg), diffusivity follows a power-law dependence with size, and below or near Tg, the diffusion is activated (i.e., the diffusivity scales with temperature as ln Dc ∝ −Ea/kBT, where Ea is the activation energy). Coarse-grained models seem to predict Ea ∝ aw2, which contrasts our linear scaling in the all-atom model.70 Our system lies slightly above the glass–rubber crossover, with T/Tg ≈ 1.2 (see SI), the segmental relaxation is on the order of the penetrant caging time (see SI), and the diffusion is activated.39 This classifies the system into the activated diffusion regime according to Kumar, but with a different size scaling. Importantly, our polymer contains water, and penetrants transit through “wet” water channels, rather than through “dry” channels as is the case in coarse-grained approaches. Whether the difference is due to water is hard to ascertain, but Zhang and Schweizer showed that a coupled dynamics in dense liquids indeed results in an exponential size dependence.64 Remapping their hard-sphere model to ours (see the SI), yields, in fact, quantitatively very similar values for the decay length λ given in eq 8.

The other important question is how do penetrants solvate in the hydrogel and what is their partition ratio. Using simulations, we compute the transfer free energy ΔG of penetrants from water into the gel (see Methods), which is related to the partition ratio Kc (in infinite-dilution limit of penetrants) as

For solvation, not only the size and shape but also the chemical character of a penetrant matters. We therefore divide the linear penetrants further into nonpolar (alkanes) and polar molecules (alcohols and water), the latter featuring the hydroxyl (OH) group (see Figure 1B). As noted before, an OH group in aromatic penetrants does not make much of a difference in the solvation.40 This is presumably because an OH group bound to a phenyl ring (to an unsaturated sp2 carbon) is less polar than in alcohols (bound to a saturated sp3 carbon),71 which is reflected also in different partial charges in the used force field.72

The results for the transfer free energy can be nicely described by the ASA and an effective molecular surface tension γ0,40,73,74

Solvation of small solutes is—similar to diffusivity—a debated topic, and alternatively to area scaling in eq 10, one can assume volume scaling or even a superposition of both.78 The volume scaling has rationale in the entropic solvation of small spherical cavities, being inversely proportional to the compressibility of the medium.79 This suggests better solvation in a less compressible medium, which is in our case the water phase (see the SI); thus it cannot explain our trends. The molecular heterogeneity of the PNIPAM phase, featuring polymer interfaces and hydrated voids, further convolutes the solvation. Our choice of the scaling with ASA (eq 10) is empirical and performs better than the scaling with volume, as we show in the SI. Nevertheless, both choices lead to qualitatively the same conclusions concerning permeability later on, since both scale with a higher power of the penetrant size than the diffusivity.

We used different definitions of penetrants’ sizes for the analyses of diffusivity (aw) and solvation (aAS), which are in accordance with respective standard practices. Fortunately, the correlation plot of both in Figure 2C reveals a clear, almost one-to-one mapping in the form of

Permeability

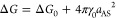

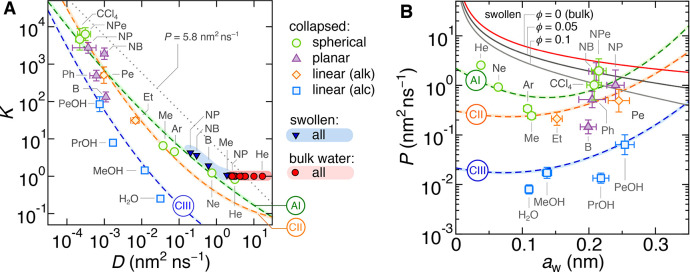

We now investigate to what extent are partitioning and diffusivity related and what role do they play in the permeability. For a start, we compose a partitioning–diffusivity correlation diagram, shown in Figure 3A. The diagonal gray dotted iso-permeability line KD = 5.8 nm2 ns–1 (the water diffusivity in bulk water) serves for orientation. All molecules in bulk water, shown by red circles in a red-shaded domain, lie on a horizontal line in the diagram (with K = 1).

(A) Partitioning–diffusivity correlation diagram. The data points in the red-shaded region correspond to bulk water (T = 300 K), the points in the light-blue-shaded region correspond to the swollen state (ϕ = 0.1, T = 300 K; shown only for Me, B, NB, NP), and the remaining data points correspond to the collapsed state (ϕ ≈ 0.8, T = 340 K). The gray dotted line is the iso-permeability line with the constant permeability of P = 5.8 nm2 ns–1. The dashed lines are predictions of the semiempirical relation eq 12 using parameter sets from Table 1. (B) Permeability as a function of the penetrant size aw. The data points are MD simulations for the collapsed state. Solid lines are theoretical results (eq 7) of the permeability in bulk water (red, ϕ = 0) and swollen states for different ϕ (gray), while the dashed lines are predictions of the semiempirical relation eq 13 for the collapsed state using the same parameter sets as in panel A.

For the swollen state we choose the polymer volume fraction ϕ = 0.1, which is typical for PNIPAM hydrogels with 5 mol % of cross-linkers.14,44 We obtain the partition coefficient Ks from eq 2 using Γm* from single-chain simulations38 and estimate the diffusion coefficient Ds from the theoretical prediction eq 6. The results for a few selected penetrants are plotted in the bottom-right corner of the diagram, encompassed in a blue-shaded domain. As seen, the swollen state covers quite a tiny region of the entire diagram, and the data points lie roughly on the same iso-permeability line. Clearly, the calculations for the swollen state are based on simple theoretical assumptions, and their sole aim is to demonstrate a mild variance in the diagram in contrast with the collapsed state, which we extensively discuss in the following.

In the collapsed state, the penetrants are much more broadly distributed across the diagram, with both Kc and Dc spanning over around 4 orders of magnitude. We can clearly notice an anticorrelation between Kc and Dc for all categories of penetrants, which leads to cancellation effects in the resulting permeability.

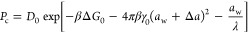

To elucidate this important observation, we return to the established semiempirical rules for Dc (eq 8) and Kc (eq 10): we merge both relations by eliminating the penetrant sizes aw and aAS, respectively, by using eq 11. This brings us to the following relation between Kc and Dc:

In Figure 3B we plot the permeabilities against the penetrants Stokes radius, aw. Theoretical predictions for swollen states (eq 7) are shown by gray solid lines (for ϕ = 0.05 and 0.1), as well as for bulk water (ϕ = 0, red line). Permeabilities of the simulated penetrants (categorized into the same four groups as in panel A) in the collapsed state, Pc, follow from the product of Kc and Dc as dictated by the solution–diffusion theory, eq 1.

To illuminate the nature of the above outcomes, we again use the semiempirical relations eqs 8 and 10, to arrive at the expression for the permeability:

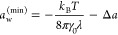

The semiempirical concepts that follow from eq 13 indicate the following: diffusion coefficients for a given shape and chemical character of molecules decay exponentially with the size, whereas partitioning rises exponentially with the square of the size. This makes the permeability nonmonotonic in terms of the penetrant’s size, with the minimum at

For spherical molecules the calculated minimum is at aw(min) ≈ 0.14 nm (slightly larger than the methane molecule), which can indeed be observed from the MD data. For linear molecules, on the other hand, the hypothetical minimum aw(min) ≈ 0.1 nm is smaller than the smallest linear molecule (water) in our study; therefore, the permeability only monotonically increases with size.

Thus, the diffusivity is more important for smaller penetrants, and, therefore, quite universally, the permeability for small molecules is rather low (except for the smallest ones, He and Ne). For larger penetrants (aw > aw(min)), the partitioning is gradually becoming more decisive for the permeability. In fact, our penetrants, with the size range between 0.05 and 0.25 nm, lie around the minimum (eq 14), where the permeability is only mildly dependent on the size. Contrarily, in the materials in which ln Dc ∝ −aw2, the size effect in Dc and Kc cancels out completely in Pc, and therefore makes the filtration on the basis of size not possible. Instead, the permeability is much more affected by the chemistry; note an order of magnitude or two lower permeabilities for polar penetrants (alcohols) compared with the other molecules of similar sizes. Thus, the collapsed state can selectively filter molecules based on their chemistry much more efficiently than on their size. Filtering on the basis of chemistry seems always operative in dense polymer systems, as we cannot foresee a mechanism that would completely compensate Dc and Kc on the prenetrant’s chemistry basis. This demonstrates the importance of the chemistry-specific penetrant–hydrogel interactions, which are lacking in simple theories and generic coarse-grained models.

Finally, we note that the substantial cancellations of the diffusivity and partitioning in PNIPAM is in considerable contrast to Overton’s rule in lipid bilayers (often egg lecithin). There, the strong dependence of P on a solute type is interpreted as the dependence of K on the solute type because diffusivity there is often only weakly dependent upon solute.80,81

Polymer Volume Fraction and Temperature

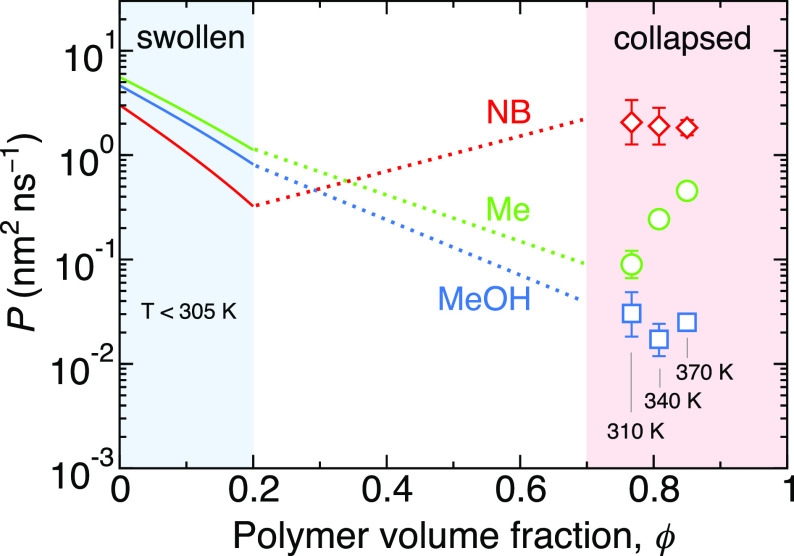

For the end, we take a look at how the permeability through the hydrogel changes with the polymer volume fraction and temperature. In Figure 4 we show the permeability for three selected penetrants: methane, methanol, and nitrobenzene. The blue- and the red-shaded areas indicate roughly the volume fractions relevant for swollen and collapsed hydrogel states, respectively, whereas the white area is a transition region, not stable in reality. The theoretical curves for swollen states (eq 7) lie close to each other; they depend only on the penetrant size. For the collapsed state, we added data for 310 and 370 K. Note that each temperature corresponds to a different polymer volume fraction, such that the sorbed water is in equilibrium with bulk. The permeability now becomes significantly penetrant-specific, and even the order changes: nitrobenzene, with the lowest permeability among the three molecules in the swollen state, becomes the most permeable one in the collapsed state.

Permeability as a function of polymer volume fraction for three penetrants: methane (Me), methanol (MeOH), and nitrobenzene (NB). The solid lines are the theoretical predictions from eq 7, relevant for swollen states (ϕ < 0.2, blue region). The symbols are simulation results of the collapsed model (red region), performed at three different temperatures and the corresponding polymer volume fractions and calculated as Pc = KcDc. The dotted lines serve as guides to the eye for connecting the swollen and collapsed states.

The volume-fraction dependence (and likewise the temperature dependence) of Pc in the collapsed state is very nontrivial. On the one hand, our previous study showed that Dc universally increases with temperature for all penetrants by the same factor;39 note that the temperature dependence is non-Arrhenius as the temperature changes also the hydration and the polymer volume fraction. But on the other hand, temperature dependence of the partitioning Kc is much more penetrant-specific. For small nonpolar molecules, Kc is almost independent of temperature. For this reason, Pc for methane increases with temperature at the expense of an increasing Dc(T). But polar penetrants and nitrobenzene solvate worse in PNIPAM at higher temperatures (in a more hydrophobic environment), and the decreasing Kc(T) compensates the increasing Dc(T).

It can be clearly seen that the collapsed state becomes extremely selective. For instance, a swollen hydrogel is comparably permeable to nitrobenzene and methanol, whereas as it collapses, it stays similarly permeable to nitrobenzene, but it practically completely blocks methanol (the permeability plummets by 2 orders of magnitude). One might naively expect the opposite, as nitrobenzene is larger than methanol and it diffuses more slowly in the collapsed state, yet the decisive factor for this switch is rather the partitioning, controlled by the polar character. Tunable permeabilities in responsive PNIPAM-based hydrogels have been experimentally demonstrated in different contexts (e.g., in controllable glucose uptake82 or switchable catalytic reactions of nitrobenzene and ionized nitrophenol14).

So far, we have learned that in the collapsed state the chemical character, shape, and size of the penetrant come much more to the fore than in swollen states. The collapsed state exhibits much richer interplay between the molecular interactions, making it much more selective for permeation (or filtration) of molecules. In other words, controlling the water content is key in determining the permeation and selective properties of a hydrogel, possibly by varying the extent of charge functionality, cross-linking, or polymer architecture and morphology. This is also the reason that highly selective commercially available membranes sorb relatively little water.83

In the end, Figure 4 also shows that permeability can change nonmonotonically with the polymer volume fraction, exhibiting minima and maxima (for the case of nitrobenzene). The notion of permeability maximization has been recently observed in generic coarse-grained models,28 but in this study, it is demonstrated in an atomistic model with a real hydrogel chemistry. The knowledge about how to sufficiently tailor and optimize the permeability is paramount to a rational design of applications in materials science. For instance, the ability to selectively transport solvent and solute molecules for the desired material function has been a grand challenge in materials science over the past decade.84,85

Conclusion

Our results, based on the solution–diffusion model and comprehensive molecular dynamics simulations, offer a well-grounded molecular basis for permeability in hydrogels. We witnessed strong anticorrelations between the diffusivity and partitioning in all states of the hydrogel and, consequently, large cancellations in the resulting permeability. In swollen states, the permeability only weakly depends on the penetrant type, meaning that there is little practical control over the permeability and selectivity. On the contrary, the permeability in the collapsed and dehydrated polymer state is extremely sensitive to tiny features of the penetrant, such as its shape, size, and chemical character, making collapsed states highly selective to tiny differences between molecules.

Strikingly, the outcomes clearly defy many well-accepted transport theories in this field, which is a reason for revisions and improvements of the current theoretical foundations in dense polymer architectures. With the gained molecular-level insights we formulated semiempirical rules for permeability of molecular penetrants of various physicochemical types for a certain membrane material. These rules are also useful to predict and understand how and why already tiny chemical modifications, such as methylation or hydroxylation, change the permeability and selectivity, in some cases even by an order of magnitude. We believe that our results will help to revise and improve the current theoretical foundations, which is crucial for a rational design of soft materials for molecule-selective transport and function. We should also mention that charged penetrants, not covered in this study, impose an additional layer of complexity, stemming from interfacial effects of water clusters.86

Finally, insights from theoretical modeling are not only limited to synthetic hydrogels but could probably also help to understand various hydrogels found in nature. Many biological gels (e.g., mucus, the extracellular matrix, biopolymers in nuclear pores, bacterial biofilms, vitreous humor) enable a selective exchange of molecules, allowing a passage of particular molecules while rejecting others.46 The underlying principles of how they manage to do this are still unknown.

Methods

We complement the simulation data for diffusivity and solubility/partitioning in the collapsed state (Figure 1A(iv)) from the previous studies39,40 by the following data. Diffusion coefficients (Dc): CCl4, NPe, Pe, Ph, PrOH, PeOH. Transfer free energies (ΔG): Ar, CCl4, NPe, Pe, PeOH. We use the same methods as in detailed described in refs (39) and (40), which we, for the reader’s convenience, briefly recap in the following. On the other hand, no additional simulations were performed for the swollen state (Figure 1A(ii)) in this study.

Atomistic Model

The collapsed state consists of 48 atactic 20-monomeric-unit-long PNIPAM chains solvated with water whose amount corresponds to the activity of bulk water. For PNIPAM polymers we use the OPLS-based force field by Palivec etal.87 For water we use the SPC/E water model,88 and the OPLS-AA force field72 for penetrant molecules.

Diffusion

The diffusion in the collapsed state is studied by inserting 10–15 penetrant molecules of the same kind at random positions into equilibrated polymer structures (using 2–4 independent replicas) and tracking their mean square displacements (MSD). The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the linear fit of the MSD in the long-time limit. The necessary simulation times span up to 8000 ns for the slowest penetrants (NPe, CCl4). The results are averaged over all the particles in the simulation box and over all replicas.

Simulation Details

The simulations are carried out using the GROMACS 5.1 simulation package89 in the constant-pressure (NPT) ensemble, where the box sizes are independently adjusted in order to maintain the external pressure of 1 bar with a Berendsen barostat90 with the time constant of 1 ps. The system temperature is controlled with a velocity-rescaling thermostat91 with a time constant of 0.1 ps. The Lennard-Jones (LJ) interactions are cut off at 1.0 nm. Electrostatic interactions are treated using particle-mesh-Ewald methods with a 1.0 nm real-space cutoff.

Solvation Free Energies

The solvation free energies of the penetrant molecules are computed using the thermodynamic integration (TI) procedure,40 where the penetrant’s partial charges and LJ interactions between the penetrant molecule and other molecules are continuously switched off. For switching off the LJ interactions we use the “soft-core” LJ functions in order to avoid singularities when the potentials are about to vanish. All the TI calculations are performed using two to five independently equilibrated systems. Final results are averaged over all the particles in the simulation box and over all the systems. The transfer free energy of a penetrant from water into the PNIPAM phase is obtained as the difference of the solvation free energies between the two respective phases.

Accessible Surface Area

To evaluate the ASA of a given molecule, we consider the molecule as a union of fused van der Waals spheres increased by the standard probe radius of 0.14 nm. The ASA corresponds to the envelope area of the fused union of the spheres.92 Note that in the previous work40 the molecular surface area was used instead, which is based on the same concept but with the probe radius of zero.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.0c06319.

Size scaling of diffusivity; glass transition temperature; chain relaxation time; comparison with the self-consistent cooperative hopping theory; compressibility of the collapsed PNIPAM state; size scaling of transfer free energy (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Acknowledgments

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (Grant Agreement No. 646659-NANOREACTOR). J.D. acknowledges the support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany’s Excellence Strategy–EXC-2193/1-390951807. M.K. acknowledges the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P1-0055). W.K.K. acknowledges the support by a KIAS Individual Grant (CG076001) at Korea Institute for Advanced Study.

How

the Shape and Chemistry of Molecular Penetrants

Control Responsive Hydrogel Permeability

How

the Shape and Chemistry of Molecular Penetrants

Control Responsive Hydrogel Permeability