- Altmetric

Background

The Mediterranean diet has been proposed to protect against neurodegeneration.

Objectives

The aim of this study was to assess the association of adherence to Mediterranean dietary pattern (MDP) at middle age with risk for Parkinson's disease (PD) later in life.

Method

In a population‐based cohort of >47,000 Swedish women, information on diet was collected through a food frequency questionnaire during 1991–1992, from which adherence to MDP was calculated. We also collected detailed information on potential confounders. Clinical diagnosis of PD was ascertained from the Swedish National Patient Register through 2012.

Results

We observed an inverse association between adherence to MDP and PD, multivariable hazard ratio of 0.54 (95% confidence interval: 0.30–0.98), comparing high with low adherence. The association was noted primarily from age 65 years onward. One unit increase in the adherence score was associated with a 29% lower risk for PD at age ≥ 65 years (95% confidence interval: 0.57–0.89).

Conclusion

Higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet at middle age was associated with lower risk for PD. © 2020 The Authors. Movement Disorders published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Background

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease worldwide, affecting approximately 1% of the population older than 60 years in Europe.1, 2 Despite our increasing knowledge about risk and protective factors, causes of PD remain largely unclear for the majority of patients. 3 Earlier studies have suggested potential roles of specific nutrients and food items on the risk for PD.3, 4 For instance, dairy products have been shown as potential risk factors for PD. 5 The associations of vitamins, antioxidants, fatty acid, alcohol, and other dietary factors with PD are, however, less conclusive.3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

Less is known, however, about the role of an overall dietary pattern, which includes not only specific food items but also the complex interactions between different items, on the risk for PD. Mediterranean dietary pattern (MDP), usually considered a healthy dietary pattern, has been suggested to have favorable effects on cancer and overall survival.14, 15, 16 Due to the anti‐inflammatory and antioxidant properties of the foods that constitute the MDP, a potential neuroprotective role of MDP has also been proposed.4, 17 A few epidemiological studies have assessed the association of MDP with PD with, however, inconsistent results.18, 19, 20, 21 Large‐scale studies with prospective data collection and life‐course perspective are needed to better understand the link between MDP and PD. 3 Thus, we investigated the association between adherence to MDP at middle age and PD risk in a population‐based cohort of Swedish women.

Materials and Methods

During 1991–1992, a random sample of all women who were aged 29 to 49 years and resided in the Uppsala region, Sweden (N = 96,000), were invited to participate in the Women's Lifestyle and Health study. 22 Among them, 49,261 consented to study participation and returned questionnaires, including a food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). 23 The mean age at enrolment was 39.7 (standard deviation: 5.8) years. Because PD is rarely diagnosed among individuals younger than 50 years, we started following the women from their 50th birthday until the date of PD diagnosis, emigration out of Sweden, death, or December 31, 2012, whichever came first, through cross‐linkages to the Swedish National Patient Register (for PD diagnosis) and Total Population Register (for emigration and death), using the individually unique personal identity numbers. 24 Among the 49,261 women who consented to study participation, we excluded 2133 who had emigrated (n = 2116) or been diagnosed with PD (n = 17) before start of follow‐up, leaving 47,128 (95.7%) in the cohort.

Women were asked to recall their dietary habits during the 6 months before enrolment using the 80 food items in the FFQ. 25 The consumption (grams/day) of each item and total energy intake (kJ/day) were calculated using the Swedish National Food Administration database. 26 To measure adherence to MDP, we used the score proposed by Trichopoulou et al, 16 as in our previous studies. 22 Specifically, we included nine food components, namely, vegetables, fruits and nuts, cereals, legumes, dairy products, fish and seafood, meat, alcohol, and monounsaturated‐to‐saturated fat ratio. An MDP score for each participant on each component was calculated based on the comparison between the individual's level of consumption and the median consumption level of the entire cohort. If the component was presumed to be beneficial (ie, vegetables, fruits and nuts, cereals, legumes, fish and seafood, and a high monounsaturated‐to‐saturated fat ratio), consumption greater than or equal to the cohort median was scored 1, whereas consumption less than the cohort median was scored 0. For components advised to be consumed in moderation or less (ie, dairy products and meat), consumption less than the cohort median was scored 1, whereas greater than or equal to the cohort median was scored 0. For alcohol, a moderate level of consumption (5–25 g/day) was scored 1, or 0 otherwise. Scores of all components were summed up to calculate an overall adherence score to MDP, with 0 as the minimum and 9 as the maximum value. In addition to the FFQ, information on demographic factors, lifestyle factors, including body mass index (BMI), physical activity, smoking status, and medical history was also collected from the questionnaires at baseline. We further excluded 547 women who had not answered the FFQ, 575 women who had extreme total energy intake [<1st (1847 kJ/day) or >99th (12,474 kJ/day) percentiles of the entire cohort], and 4291 women with missing data on the earlier covariates, leaving 41,715 (88.5%) in the final analyses (Supporting Information Fig. S1).

The clinical diagnosis of PD was ascertained through the Swedish National Patient Register, which has collected nationwide information for hospital‐based inpatient (1987 to present) and outpatient (2001 to present) care in Sweden. 27 We used the 8th to 10th Swedish revisions of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes to identify PD diagnosed before and during follow‐up (ICD‐8: 342.00; ICD‐9: 332A, 333A; and ICD‐10: G20, F023, G214, G218, G219, G231, G232, G239, G259, G318A). Date of first hospital visit concerning PD was used as date of PD diagnosis. Our previous validation study has demonstrated a satisfactory positive predictive value of PD diagnosis using inpatient care records from the Swedish Patient Register. 28 Although the quality of PD diagnosis using outpatient care records is yet to be evaluated, a higher positive predictive value might be expected because of its specialist care–based nature.

Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained from Cox models, using attained age (age at follow‐up) as the underlying time scale. Score of adherence to MDP was analyzed both as a categorical (classified according to tertile distribution: low/0–3, medium/4–5, and high/6–9) and continuous (per unit increase) variable. The P value for trend was derived from Wald's test to test the statistical significance of the dose‐response relationship when adherence to MDP was used as a categorical variable. We first examined the association of adherence to MDP with PD during the entire follow‐up and then separately for attained age <65 and ≥65 years, because 65 years was the most common age of retirement in Sweden, and the risk for PD is greatly age dependent. In the age‐stratified analysis, we compared high or medium adherence with low adherence to MDP because of reduced numbers of PD cases. In the minimally adjusted model, in addition to attained age, we adjusted for year of birth in 5‐year intervals (1942–1946, 1947–1951, 1952–1956, and 1957–1962). In the fully adjusted model, we additionally controlled for potential confounding by BMI (<25, ≥25 and <30, and ≥30 kg/m2), years of education (0–10, 11–13, and >13), level of physical activity (very low, low, moderate, high, and very high), smoking (never, former, and current), diabetes history (yes/no), hypertension history (yes/no), and total energy intake (kJ/day), because these factors have been suggested as potential risk or protective factors for PD. 3 The proportional hazards assumption of Cox regression was examined by Schoenfeld residuals, 29 and no clear violation was found. Because the incidence of PD increases quickly with age, we also used flexible parametric models 30 to assess the incidence rates and HRs (95% CIs) of PD in relation to adherence to MDP by attained age, after adjusting for all of the earlier mentioned covariates.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and STATA version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). This study was approved by Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden.

Results

Supporting Information Table S1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study participants. Women with a higher adherence to MDP tended to be older at cohort entry, had more years of education, were more physically active, were nonsmokers, and had a higher total energy intake, compared with women of a lower adherence. During the median follow‐up of 10.9 years, 101 women received a diagnosis of PD. The median follow‐up was 10.9 years for the patients with PD (8.8 years for patients with PD diagnosed before age 65 and 17.0 years for patients with PD diagnosed at age 65 years or above).

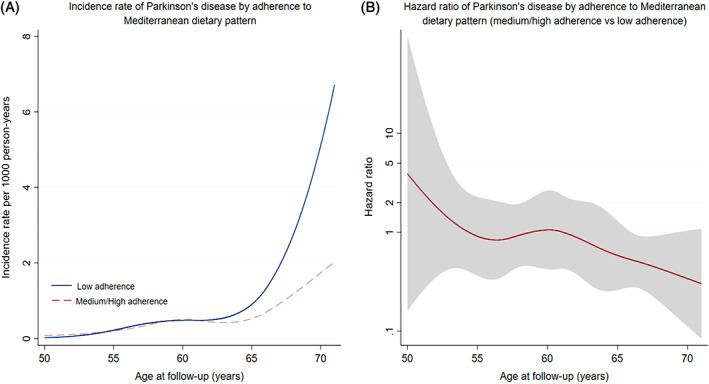

Women with a high adherence to MDP had a lower risk for PD (fully adjusted HR, 0.54; 95% CI: 0.30–0.98), compared with women with a low adherence (Table 1). The association was primarily noted among women at age 65 years or older (fully adjusted HR, 0.43; 95% CI: 0.21–0.87, medium/high adherence vs low adherence). One unit increase in the adherence score was associated with a 11% lower risk for PD overall (fully adjusted HR, 0.89; 95% CI: 0.78–1.01; P = 0.06) and a 29% lower risk for PD at age 65 years or older (fully adjusted HR, 0.71; 95% CI: 0.57–0.89). The incidence rates of PD increased with age, and from age 65 years onward there was a much more rapid increase among women with low adherence to MDP than women with medium or high adherence to MDP (Fig. 1A). An inverse association between medium or high adherence to MDP and a lower risk for PD was also noted from age 65 years or older (Fig. 1B).

| Adherence to MDP | No. of Cases/Participants | Minimally Adjusted HR (95% CI) a | Fully Adjusted HR (95% CI) b |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entire follow‐up | |||

| Low (0–3) | 37/14163 | Reference category | Reference category |

| Medium (4–5) | 47/18181 | 0.89 (0.58–1.37) | 0.87 (0.56–1.35) |

| High (6–9) | 17/9371 | 0.55 (0.31–0.99) | 0.54 (0.30–0.98) |

| P for trend c | — | P = 0.052 | P = 0.049 |

| Per unit increase | 101/41,715 | 0.89 (0.79–1.01) | 0.89 (0.78–1.01) |

| Age at follow‐up < 65 years | |||

| Low (0–3) | 22 | Reference category | Reference category |

| Medium/high (4–9) | 48 | 1.01 (0.61–1.68) | 1.00 (0.60–1.66) |

| Per unit increase | 70 | 0.99 (0.85–1.14) | 0.98 (0.85–1.14) |

| Age at follow‐up ≥ 65 years | |||

| Low (0–3) | 15 | Reference category | Reference category |

| Medium/high (4–9) | 16 | 0.44 (0.22–0.89) | 0.43 (0.21–0.87) |

| Per unit increase | 31 | 0.71 (0.57–0.89) | 0.71 (0.57–0.89) |

a HRs and 95% CIs derived from Cox models using attained age as time scale, adjusted for year of birth.

b Further adjusted for body mass index, smoking, physical activity, total energy intake, education, diabetes, and hypertension.

c P value for trend was derived from Wald's test.

Abbreviations: MDP, Mediterranean dietary pattern; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. Bold values are statistically significant.

(A) Incidence rate of Parkinson's disease (PD) by age at follow‐up among women with different adherences to Mediterranean diet. (B) Hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval of PD by age at follow‐up among women with different adherences to Mediterranean diet.

Discussion

In a large population‐based cohort study of women, we found that a higher adherence to the MDP at middle age was associated with a lower risk for PD later in life. In animal and clinical studies, MDP has been associated with several neuroprotective pathways, including anti‐inflammation, antioxidation, gut‐microbiota‐brain axis, and ketogenic properties. 4 Previous epidemiological studies have, however, reported less consistent results on the association of MDP or other healthy dietary pattern with the risk for PD.18, 19, 20, 21, 31, 32 The inconsistent results might be attributable to the varying study design, sample size, definition of PD, and possibility of residual confounding because of lack of control for important confounders, as well as the different tools for MDP assessment and study populations used. For instance, two cross‐sectional studies reported an inverse association between adherence to MDP and PD 19 or prodromal PD, 21 whereas another reported a null association. 20 One case‐control study in Japan found an association between healthy diet (high intake of vegetables, fruits, and fish) and a lower risk for PD, but no association for “Western” or “Light meal” pattern. 32 A Finland cohort study reported a null association between healthy eating index and risk for PD, 31 whereas a cohort study from the United States linked healthy dietary patterns, including MDP, to a lower or a tendency to lower risk for PD, 18 corroborating the present study of a large cohort of Swedish women. Apart from reducing the PD risk, dietary and nutritional factors have also been shown to improve symptoms and quality of life among patients with PD, such as low‐fat and ketogenic diet, 33 nutritional supplement,34, 35 and improved overall nutritional status. 36

Strengths of our study include the population‐based design, the large sample size, the virtually complete follow‐up, and the prospective and independent collection of information on diet and PD. There are several limitations in this study. We had no repeated measurement of FFQ and could not assess change of adherence to MDP among the study women. Nevertheless, dietary habits seem to be a lifelong behavior and are not very dynamic.37, 38 Although the PD definition based on the Swedish Patient Register has been shown with satisfactory positive predictive value, 28 here was likely a delay between the actual diagnosis of PD and the first hospital visit for PD (used as date of diagnosis in this study), due to the specialist care–based nature of the register. Similarly, we might have misclassified some patients with PD who were yet attended by specialist as free of PD. The study population was relatively young, and a follow‐up study is needed to assess the role of MDP on PD at more advanced age. 39 Further, because we lacked information on family history of PD, we could not assess whether adherence to MDP would have a different association with PD among women with and without such a family history. Finally, because of the observational nature of the study, residual confounding cannot be completely ruled out, even if we adjusted for a rich set of potential confounders, including sociodemographic, lifestyle (eg, smoking, BMI, physical activity), and medical factors. The fact that current smoking was found to be associated with 50% lower risk for PD (HR 0.51, 95% CI: 0.29–0.87) in this study, which is greatly similar with previous reports, 40 argues, however, against the existence of very strong residual confounding.

Conclusions

Higher adherence to a Mediterranean diet at middle age was associated with lower risk for PD in later life among Swedish women.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Fang Fang reports grants from Swedish Research Council, Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare, and Karolinska Institutet, during the conduct of the study.

Author Roles

(1) Research Project: A. Conception and Design; B. Acquisition of Data; C. Analysis and Interpretation of Data

(2) Manuscript: A. Writing of the First Draft; B. Review and Critique

(3) Other: A. Supervision of Project; B. Coordination of Project; C. Funding Support

W.Y.: 1A, 1C, 2A

M.L.: 2B, 3B

N.L.P.: 2B, 3B

S.S.: 1A, 1B, 2B, 3A, 3B

F.F.: 1A, 1B, 2B, 3A, 3B, 3C

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Swedish Research Council (grant no. 2019‐01088), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (grant no. 2017‐00531), and the Karolinska Institutet (Senior Researcher Award and Strategic Research Area in Epidemiology).

References

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

Mediterranean Dietary Pattern at Middle Age and Risk of Parkinson's Disease: A Swedish Cohort Study

Mediterranean Dietary Pattern at Middle Age and Risk of Parkinson's Disease: A Swedish Cohort Study