- Altmetric

In recent years, codon substitution models based on the mutation–selection principle have been extended for the purpose of detecting signatures of adaptive evolution in protein-coding genes. However, the approaches used to date have either focused on detecting global signals of adaptive regimes—across the entire gene—or on contexts where experimentally derived, site-specific amino acid fitness profiles are available. Here, we present a Bayesian site-heterogeneous mutation–selection framework for site-specific detection of adaptive substitution regimes given a protein-coding DNA alignment. We offer implementations, briefly present simulation results, and apply the approach on a few real data sets. Our analyses suggest that the new approach shows greater sensitivity than traditional methods. However, more study is required to assess the impact of potential model violations on the method, and gain a greater empirical sense its behavior on a broader range of real data sets. We propose an outline of such a research program.

Introduction

Codon substitution models (Goldman and Yang 1994; Muse and Gaut 1994) are among the important modern tools used for uncovering potential signals of molecular adaptation from protein-coding gene alignments. One set of broadly used models focuses on estimating the ratio of rates of nonsynonymous (dN) and synonymous (dS) substitutions. These models introduce a multiplicative parameter, denoted ω, to entries in a codon substitution matrix corresponding to nonsynonymous events. Because ω is the only distinction between the rate specification of nonsynonymous and synonymous events, it directly corresponds to .

Fitting a model with a single (global) nonsynonymous multiplicative parameter almost always leads to

Meanwhile, another set of codon substitution models was proposed, with a focus on accounting for purifying selection at the amino acid level in a site-heterogeneous manner (Halpern and Bruno 1998). Having nucleotide-level parameters controlling a mutational process, and amino acid fitness profiles controlling selection, they have come to be known as mutation–selection models (e.g., Yang and Nielsen 2008; Rodrigue et al. 2010). In these models, the dN/dS ratio is not explicitly parameterized. Instead, it is an emerging quantity, induced by the interplay between mutation, selection, and drift. Spielman and Wilke (2015) have shown how to calculate the dN/dS induced by the mutation–selection framework—which we denote ω0 (Rodrigue and Lartillot 2017)—and found that, under specific conditions (i.e., a substitution process at equilibrium, without selection on synonymous variants), it is always true that

In the last few years, the mutation–selection framework has been extended for the purpose of detecting genes having evolved under an adaptive regime, in either a global (Rodrigue and Lartillot 2017) or site-specific (Bloom 2017) manner. Like their traditional predecessors, these recent mutation–selection models introduce a multiplicative parameter on nonsynonymous rates. However, because amino acid profiles are also involved in modulating nonsynonymous rates, such a multiplicative parameter—which we denote as

New Approaches

Here, we conduct the first exploration of a Bayesian mutation–selection model with site-heterogeneous amino acid fitness profiles and site-heterogeneous

Results and Discussion

Models with Global ω or ω *

We first contrasted the difference in behavior between a traditional codon substitution model inspired from Muse and Gaut (1994), with a global ω parameter (a traditional model we denote MG-M0, described in detail in the Materials and Methods section), and a mutation–selection model with a Dirichlet process prior on amino acid profiles across sites and a global

Simulations

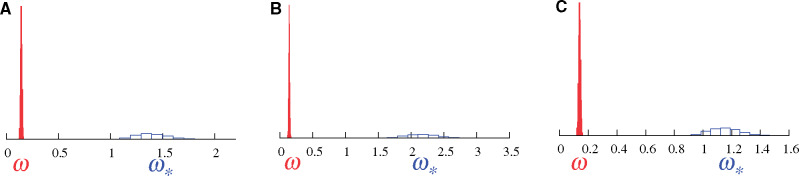

Figure 1 shows results of the two models on data generated through a simulation approach explicitly allowing for fluctuating selection at some sites; for these sites, amino acid fitness profiles change along the branches of the phylogeny, as described in Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017) and in the Materials and Methods section. The simulation system is an attempt at mimicking an adaptive substitution process, where the simulated substitution history tracks a changing amino acid fitness optimum along the branches of the tree, and thus accrues more nonsynonymous substitutions than expected under a pure nearly neutral regime (i.e., mutation–selection balance). An important distinction with Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017) is that here the simulated data set contains only 10% of codon sites generated under adaptive regimes, and 90% of codon sites generated under a pure nearly neutral mutation–selection formulation (Rodrigue et al. 2010). We produced alignments of 300 codons in length, repeating the simulation thrice, with different sets of empirically inferred amino acid profiles (see Lowe and Rodrigue 2020, and the Materials and Methods section).

Posterior distributions of ω (red, under MG-M0) and

Results under the traditional MG-M0 model (red) reflect the overall purifying selection governing most of the data-generating processes, with posterior mean ω values at 0.14, 0.15, 0.13 in three replicates displayed in panels 1A, 1B, and 1C, respectively. The fact that 10% of sites where produced under an adaptive regime is underwhelming to the MG-M0 model, and indeed little is generally expected of it in practice. Results under the MutSel-M0* model (blue) show a posterior distribution for

Previous studies (Rodrigue and Lartillot 2017; Lowe and Rodrigue 2020) have shown that a simulation conducted with 100% of sites under the pure nearly neutral mutation–selection formulation leads to a posterior distribution of

Real Data

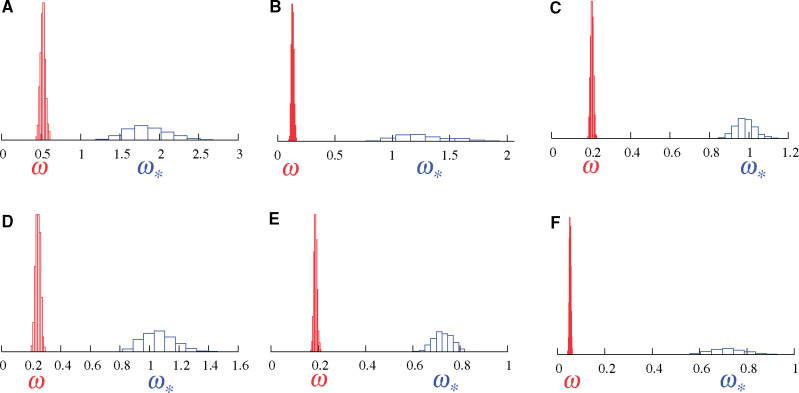

Figure 2 shows the results of these models on a hand-full of real alignments. Figure 2A displays the results on the well-known β-Globin alignment sampled across 17 vertebrates (Yang et al. 2000). As in the simulation, the MG-M0 model indicates that

Posterior distributions of ω (red, under MG-M0) and

Figure 2B displays results on an alignment of the alcohol dehydrogenase (Adh) gene sampled across 23 species of Drosophila. Here again, the MG-M0 model indicates that

The four remaining panels of figure 2 (C–F) show results on four genes sampled across placental mammals (Lartillot and Delsuc 2012). Again,

Models with Heterogeneous ω or ω *

In spite of the potential of the MutSel-M0* model—able to capture relatively subtle signals of adaptive evolution—it still does not directly allow us to pinpoint which sites are most responsible for such signals. This is one of the motivations of site-models. Classical site-models (Nielsen and Yang 1998; Yang et al. 2000; Yang and Swanson 2002) consider alignment sites as having been produced from a distribution of possible ω values. They are typically used in the context of an empirical Bayes approach for identifying sites with a strong statistical support for a

To illustrate this point, and for simplicity here, we work with the classical MG-M3 model, inspired from Muse and Gaut (1994) and Yang et al. (2000), which invokes a finite mixture of three ω values—with their respective weights—jointly estimated with all other parameters given the data. We also study a new model referred to as MutSel-M3*, which is built from a finite mixture of three

Simulations

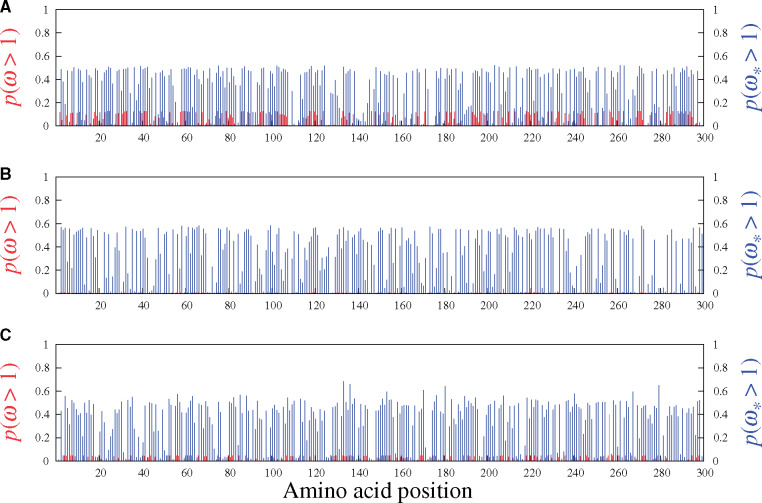

As a verification, figure 3 shows the results under the MG-M3 (red) and MutSel-M3* (blue) models on three simulated data sets, this time generated entirely under the pure mutation–selection framework (i.e., no adaptive regimes within the data-generating processes). In accordance with the simulation, no sites have high probabilities of having

Site-specific posterior probabilities of ω (red, under MG-M3) and

These simulations also highlight an inherent risk built into the MutSelM3* model’s construction, in comparison with MG-M3: the threshold for a site to considered of interest—in terms of potential adaptive evolution—is much closer to the value expected under the null (of no adaptive regime) under MutSelM3* than under MG-M3, with the latter reporting site-specific probabilities of having

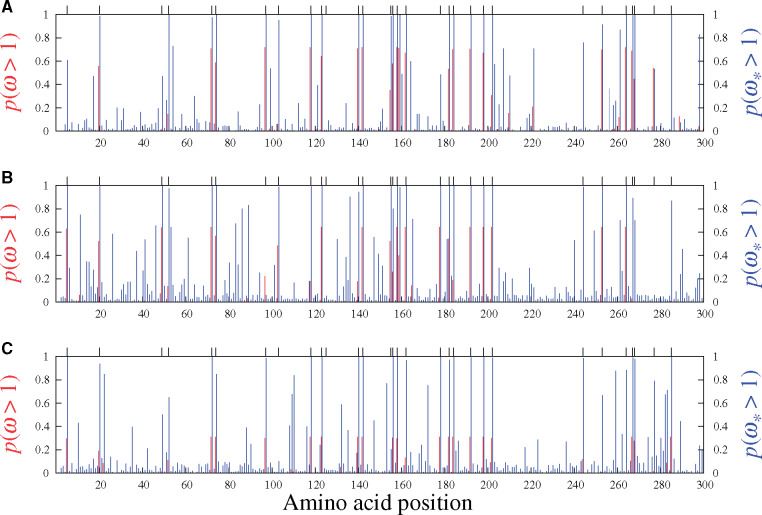

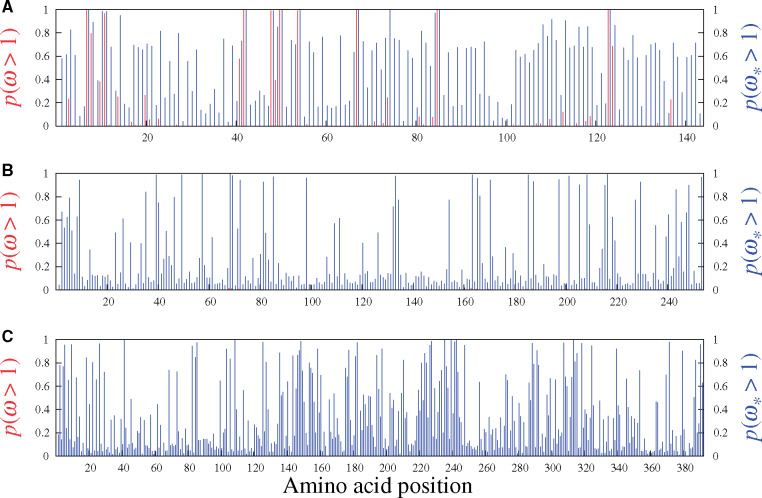

Figure 4 shows the results on the three simulated data sets studied in figure 1 (i.e., with 10% of sites simulated with an adaptive regime). The panels include vertical marks at the top, showing the 30 codon sites simulated under adaptive regimes. Sites evolving under an adaptive regime tend to accrue more nonsynonymous substitutions than under a nearly neutral regime, which would shift

Site-specific posterior probabilities of ω (red, under MG-M3) and

Real Data

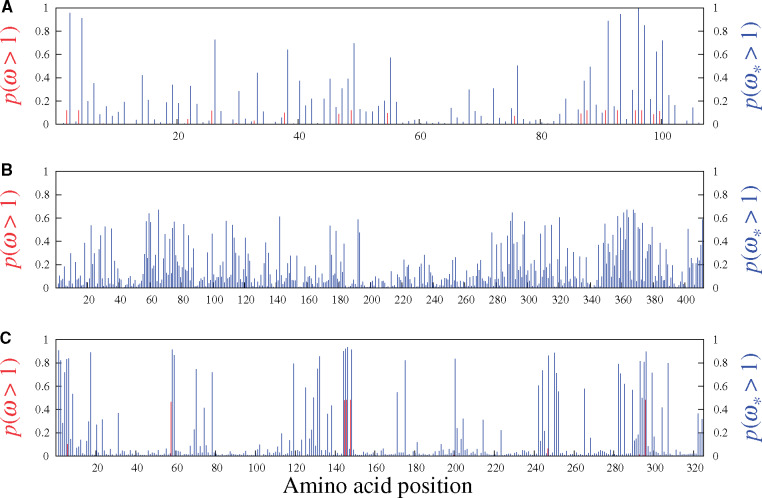

Figures 5 and 6 display the results obtained from analyzing the six real data sets mentioned above with the MG-M3 and MutSel-M3* models. For the β-Globin alignment (fig. 5A), our Bayesian version of the classic MG-M3 model leads to the same set of sites identified with these traditional models in the maximum likelihood context (Yang et al. 2000): at the 95% threshold, the sites are 7, 11, 42, 48, 50, 54, 67, 85, and 123. Under the MutSel-M3* model, these same sites are also found, and the following three are added: 10, 74, and 84. (The complete lists of sites identified at different thresholds are reported in table 1.) It is interesting to note that the MG-M3 model found

Site-specific posterior probabilities of ω (red, under MG-M3) and

Site-specific posterior probabilities of ω (red, under MG-M3) and

| Data | Model | Sites |

|---|---|---|

| MG-M3 | 7, 11, 42, 48, 50 54, 67, 85, 123 | |

|

| ||

| MutSel-M3* | 7, 10, 11, 14, 42, 48, 50 54, 67, 74, 84, 85, 110, 113, 123 | |

| MG-M3 | – | |

| Adh | ||

| MutSel-M3* | 9, 39, 49, 57, 68, 69, 72, 81, 85, 98, 133, 163, 165, 170, 185, 187, 197, 201, 205, 208, 216, 229, 253 | |

| MG-M3 | – | |

| Vwf | ||

| MutSel-M3* | 5, 9, 26, 41, 82, 85, 103, 108, 125, 147, 148, 158, 177, 182, 197, 226, 227, 235, 239, 241, 242, 247, 288, 291, 307, 313, 318, 324, 339, 371, 379, 390 | |

| MG-M3 | – | |

| Adora3 | ||

| MutSel-M3* | 2, 4, 93, 96 | |

| MG-M3 | – | |

| Rbp3 | ||

| MutSel-M3* | – | |

| MG-M3 | – | |

| S1pr1 | ||

| MutSel-M3* | 1, 58, 144, 145, 146, 148 |

Note.—Numbers in italic font are at the 0.9 level, in plain font at the 0.95 level, and in bold font at 0.99 level.

The sites uncovered by MutSel-M3* on the β-Globin data set are conditional on the overall construction of the model, which makes many oversimplified assumptions. As such, the list of sites should be considered provisional, in need of more thorough investigation by external means, and in the context of a larger scale application of the model. Some of the model violations potentially at play here, and that have mislead other types of approaches to detecting adaptive evolution, include variable effective population size (Rousselle et al. 2018), biased gene-conversion (Ratnakumar et al. 2010), multinucleotide mutations (Venkat et al. 2018), and nonhomogeneous/nonneutral synonymous substitution rates (Wisotsky et al. forthcoming). Richer simulation studies will be needed to better understand how the MutSel-M3* model reacts to such violations, and the extent to which they could be responsible for false positives.

Results of the analysis of Adh (fig. 5B, table 1) suggest several sites under adaptive evolution under the MutSel-M3* model, whereas the MG-M3 yields posterior probabilities of

As with the analyses of the β-Globin data set, much more work will be required to determine the plausibility of these new results on the Adh data set. In addition to the aforementioned potential model violations, with a sampling across Drosophila, which have high effective population sizes, features such as uneven codon usage can become highly pronounced (Powell and Moriyama 1997), potentially misleading inferences of site-specific adaptation as well. As a hypothetical example, suppose that the codon TTG is used almost exclusively for encoding leucine, and that GTG is similarly strongly favored for encoding valine. Also suppose that leucine and valine are of equivalent fitness at a given site. In such a context, nonsynonymous substitutions between TTG and GTG accumulate more readily than synonymous substitutions. If this feature were to be present to a high extent, it could mislead the MutSel-M3* model into inferring

Our analysis of the mammalian-level alignment of the gene Vwf also suggests several sites with adaptive signatures under the MutSel-M3* model, and none under the MG-M3 model (fig. 5C, table 1). A previous study, utilizing branch-heterogeneous models, has suggested adaptive evolution conferring venom resistance to opposoms that prey on pitvipers (Jansa and Voss, 2011). Moreover, variants of this gene have been found to have dramatic effects on its own expression levels in mice (Lemmerhirt et al. 2006), and hence with high potential for strong fitness effects.

While these latter studies are precedents to finding sites with signatures of adaptive evolution under the MutSel-M3* model, many of the model violations mentioned above could apply here as well. At the mammalian scale of this Vwf data set, a mutation–selection-based test of selection on codon usage has been shown to be misled by the effect of CpG hypermutability (Laurin-Lemay et al. 2018). This context-dependent mutational feature could have the effect of inflating

Of the remaining mammalian gene alignments studied with the MutSel-M3* model, two suggest very few sites having evolved under adaptive regimes (Adora3 and S1pr1, in fig. 6A and C, respectively), and one (Rbp3, fig. 6B) with none. The traditional MG-M3 model suggests no sites under adaptive evolution for these data sets. These three genes may be typical of results under the MutSel-M3* model at the mammalian scale (i.e., few, if any sites with high

Future Directions

The traditional codon models based on ω have become increasingly well understood thanks to decades of empirical applications and simulation studies. A similar project should be considered within the mutation–selection framework. We have already suggested several lines of research meriting further attention, and we expand on these themes below.

Simulation Studies

A flurry of recent research has shown how a variety of approaches are highly susceptible to model violations, with many instances of purported signals of molecular adaptation being the result of unaccounted features of the evolutionary process (e.g., Ratnakumar et al. 2010; Rousselle et al. 2018; Venkat et al. 2018; Laurin-Lemay et al. 2018; Wisotsky et al. forthcoming). From the codon substitution modeling perspective, this raises important questions regarding the mutation–selection-based approach we propose here: whereas the biological expectation under traditional models is for ω values closer to 0 than to 1, such that

Empirical Studies

A more detailed examination, ideally combined with experimental corroborations, of the sites uncovered by the model is pressing, and hopefully based on far more than the hand-full of data sets of the present study. This would help build our empirical understanding how the model behaves in a variety of different contexts (Moutinho et al. 2019; Slodkowicz and Goldman 2020). We hope to apply the model on a few thousand genes from the OrthoMamm database (Scornavacca et al. 2019) in a first step, before engaging broader applications across varied taxanomic contexts.

Model Variations

While we have outlined the modeling strategy with a three-component finite mixture of

Applications

We propose these modeling ideas in two independent software packages (see below). One of our Markov chain Monte Carlo implementations can run under fixed topology as well as sample over trees, and thus enable studies of the impact of phylogenetic uncertainty in inferences of adaptive evolution, utilizing both traditional and mutation–selection codon substitution models; this also suggests more extensive studies on the potential of such models for phylogenetic inference per se. Another implementation we offer lends itself to integrative modeling objectives, with a wide suite of potential research avenues utilizing the mutation–selection-based approaches. Foreseeable directions in the short-term with the latter implementation include capturing the evolution of effective population size over the phylogeny, along with joint inferences of continuous-trait evolution, as formalized by Lartillot and Poujol (2011).

Materials and Methods

Simulated Data

We used the simulation system described in Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017) to generate artificial data sets using a mutation–selection framework with global mutation parameters and site-specific amino acid fitness profiles. The mutation-level parameters (which assume no selection on synonymous variants) are as given in Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017), as is the phylogenetic tree (with 38 tips). With nearly neutral simulations (i.e., with the pure mutation–selection formulation, such as detailed below), the amino acid fitness profile used to simulate a codon site is chosen at random from a set of empirically derived profiles. We obtained such profiles by running the pure Dirichlet process-based mutation–selection model (Rodrigue et al. 2010) on a multigene data set at the scale of placental mammals (Lartillot and Delsuc 2012), and calculating the posterior mean amino acid profile at each site. The simulation draws at random (with replacement) one such site-specific posterior mean profile to run the evolutionary process along the tree at one codon site, repeating to produce alignments of 300 codons. For simulations with adaptive evolutionary regimes, the starting profiles are altered along the branches of the phylogeny as detailed in Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017), with the Red Queen parameter set to 0.01. In contrast to the simulations in Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017), however, the adaptive simulations herein are applied to only 10% of sites of the alignment; these 30 sites were chosen at random, that is, they were spread out randomly across the alignment. The remaining 270 codon sites are simulated with the Red Queen parameter set to 0, thus constituting pure mutation–selection regimes.

Real Data

We used previously studied alignments of protein-coding genes provided by the authors of earlier works:

β-Globin: 17 vertebrate sequences of β-globin gene, 144 codons in length, taken from Yang et al. (2000);

Adh: 23 Drosophila sequences of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene, 254 codons in length, taken from Yang et al. (2000);

Vwf: 62 sequences, at the scale of placental mammals, of the von Willbrand factor gene, 392 codons in length, taken from Lartillot and Delsuc (2012), as were the next three alignments;

Adora3: 67 sequences of the adenosine receptor A3 gene, 107 codons in length;

Rbp3: 54 sequences of the retinol-binding protein 3, 412 codons in length;

S1pr1: 67 sequences of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 gene, 325 codons in length.

Substitution Models

The MG-M0 codon substitution model, inspired from Muse and Gaut (1994), but with a single ω parameter distinguishing nonsynonymous events, has entries given as:

Here, μij is the mutational parameterization, which we set as a general-time reversible nucleotide-level model (Lanave et al. 1984), with six exchangeability parameters (five degrees of freedom) and four frequency parameters (three degrees of freedom). The MG-M3 model has the same form, but rather than a single ω parameter, it invokes three different values (with their respective weights), and has a likelihood function consisting of the a weighted average of likelihood scores under each of the three ω values (Yang et al. 2000).

The MutSel-M0* model, presented in Rodrigue and Lartillot (2017), is given as:

Priors

Branch lengths are endowed with an exponential prior of mean controlled by a hyperprior, itself endowed with an exponential prior of mean 1. Nucleotide exchangeabilities and frequencies are each endowed with flat Dirichlet priors, whereas ω and

Data Availability

For convenience, all data sets (simulated and real) studied herein are included in the Supplementary Material.

The models presented have been implemented in an experimental version (2) of PhyloBayes-MPI (https://github.com/bayesiancook/pbmpi2), allowing for a joint sampling across parameter space, auxiliary variables, and tree topology space. We have also implemented the models in a new software called BayesCode, which is focused on integrative comparative methods under fixed topology (https://github.com/bayesiancook/bayescode). Example scripts demonstrating the use of the software are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

The work was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (N.R.), and the French National Research Agency, Grant ANR-15-CE12-0010-01/DASIRE (T.L., N.L.).

A Bayesian Mutation–Selection Framework for Detecting Site-Specific Adaptive Evolution in Protein-Coding Genes

A Bayesian Mutation–Selection Framework for Detecting Site-Specific Adaptive Evolution in Protein-Coding Genes