Competing Interests: Yu-Chen Yeh and Xiaocong L. Marston are employees of Pharmerit International, who were paid consultants to Pfizer in connection with this study. Ahmed Shelbaya and Joseph C. Cappelleri are employees and stockholders of Pfizer Inc. The study was sponsored by Pfizer. All authors had a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, and preparation of the manuscript. The sponsorship of Pfizer did not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

- Altmetric

Objective

To examine pregabalin dose titration and its impact on treatment adherence and duration in patients with neuropathic pain (NeP).

Methods

MarketScan database (2009–2014) was used to extract a cohort of incident adult pregabalin users with NeP who had at least 12 months of follow-up data. Any dose augmentation within 45 days following the first pregabalin claim was defined as dose titration. Adherence (measured by medication possession ratio/MPR) and persistence (measured as the duration of continuous treatment) were compared between the cohorts with and without dose titration. Logistic regressions and Cox proportional hazards models were used to identify the factors associated with adherence (MPR ≥ 0.8) and predictors of time to discontinuation.

Results

Among the 5,186 patients in the analysis, only 18% of patients had dose titration. Patients who had dose titration were approximately 2.6 times as likely to be adherent (MPR ≥ 0.8) (odds ratio = 2.59, P < 0.001) than those who did not have dose titration. Kaplan-Meier analysis shows that the time to discontinuation or switch was significantly longer among patients who had dose titration (4.99 vs. 4.04 months, P = 0.009).

Conclusions

Dose titration was associated with improved treatment adherence and persistence among NeP patients receiving pregabalin. The findings will provide valuable evidence to increase physician awareness of dose recommendations in the prescribing information and to educate patients on the importance of titration and adherence.

Introduction

Neuropathic pain and treatment

Neuropathic pain (NeP), defined as “pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nerve system”, is a syndrome derived from a range of etiologies such as diabetes mellitus, spinal cord injury, shingles, multiple sclerosis, tumor compression, stroke, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection[1, 2]. NeP negatively impacts patients’ quality of life (QoL) and limits their daily activities [3–5]. The estimated prevalence of NeP varies from 6.9% to 10% in the general population [6]. In terms of the economic burden of NeP, indirect costs due to absenteeism and decreased productivity were the primary cost driver, totaling $100 billion each year in the US [7]. Currently, there is no curative treatment for NeP and the goal of treatment is to achieve symptom control [8]. Based on the guidelines, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g., amitriptyline and nortriptyline), calcium channel alpha-2-delta ligands (e.g., gabapentin and pregabalin), and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) (e.g., duloxetine and venlafaxine) are recommended as first-line options for NeP treatment, whereas tramadol and other opioids are considered as second-line agents [8–14].

Pregabalin (LYRICA, Pfizer), a ligand of the alpha-2-delta (α-2-δ) subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels [15], was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of NeP associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (DPN), post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN), fibromyalgia, spinal cord injury and adjunctive therapy for the treatment of partial onset seizures in patients four years of age or older [16]. Data from randomized controlled trials showed that pregabalin had early and sustained effect on pain relief for NeP, as well as a beneficial effect on related sleep interference [17, 18]. Pregabalin has also been proved to be well tolerated with a low discontinuation rate when titrated over one week to fixed dosages [18].

Treatment adherence and dose titration

Whilst efficacy of medicines in clinical trials is generally well demonstrated, the effectiveness of a pharmacological treatment in clinical practice is strongly influenced by patient adherence. Indeed, nonadherence remains a challenging problem in NeP management. One Swedish study reported that more than half of the patients discontinued their NeP treatment after the first three months while 60–70% discontinued after six months [19]. Gharibian et al. explored the adherence and persistence among patients in the US who received antidepressants and anticonvulsants for NeP and noted that less than 50% of the patients were adherent or persistent during the first-year treatment [20]. Non-adherence was associated with poor disease control and increased healthcare resource utilization and costs [21–25].

Adherence to medication refers to the extent to which patient behavior matches health advice [26]. There are numerous factors that can negatively affect patient adherence, including concerns about side effects, fears of addiction, lack of sufficient patient education, and poor efficacy or tolerability [27, 28]. The aim of pregabalin dose titration is to achieve the optimal balance between efficacy and tolerability. The prescribing information suggests that pregabalin be started at 150 mg/day [29]. The dose may be increased to 300 mg/day within one week. Further increase in dose may be considered depending on the indication [29].

Studies have shown that dose titration was associated with improved pain relief. A pooled analysis of seven placebo-controlled clinical trials of pregabalin in DPN showed that increased doses were associated with greater pain relief [30]. In a recent simulation study using integrated data from nine clinical trials and an open-label observational study, researchers found that upward dose titration to 300 mg/day was associated with greater proportions of pain relief regardless of baseline pain severity in patients with DPN [31]. Serpell et al. conducted an in-depth analysis of six flexible-dose clinical trials of pregabalin in patients with NeP. The study found that many patients who do not respond to lower doses of pregabalin will respond with notable improvements in pain outcomes when the dose is escalated [32].

In addition to improved clinical outcomes, dose titration was also associated with improved medication adherence and persistence in patients with various conditions [33, 34]. However, existing research is scarce on the relationship between pregabalin dose titration and adherence and persistence among patients with NeP. The aim of this study was to improve the knowledge on real-world use of pregabalin and the effect of dose titration on treatment adherence and persistence utilizing a large commercial claims database.

Materials and methods

This was a retrospective cohort study of NeP patients initiating pregabalin treatment during the study period.

Materials

Data from the Truven MarketScan Commercial and Medicare Supplement Database from 2009 through 2014 were used to extract a cohort of incident adult pregabalin users with NeP (DPN, PHN, and spinal cord injury, Table 1). The MarketScan database contains claims of approximately 100 employers and 12 US health plans representing more than 30 million covered lives including employees and adult dependents. The Commercial database includes health plan data for individuals younger than 65 years of age, whereas the Medicare Supplemental database includes predominantly fee-for-service plan data for Medicare-eligible retirees aged 65 and older with employer-sponsored Medicare Supplemental plans.

| Variable | Total N = 5,186 | With pregabalin dose titration N = 933 | Without pregabalin dose titration N = 4,253 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 53 (8.6) | 52 (9.1) | 53 (8.5) | 0.010 |

| Median (Q1 to Q3) | 55 (49, 59) | 54 (48, 59) | 55 (49, 59) | |

| Range | 18, 64 | 18, 64 | 18, 64 | |

| Age group, n (%) | ||||

| 18–44 years | 729 (14.1%) | 159 (17.0%) | 570 (13.4%) | 0.004 |

| 45–64 years | 4,457 (85.9%) | 774 (83.0%) | 3,683 (86.6%) | |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 2,720 (52.5%) | 478 (51.2%) | 2,242 (52.7%) | 0.411 |

| Female | 2,466 (47.6%) | 455 (48.8%) | 2,011 (47.3%) | |

| Region, n (%) | ||||

| North Central | 1,211 (23.4%) | 224 (24.0%) | 987 (23.2%) | 0.052 |

| Northeast | 576 (11.1%) | 124 (13.3%) | 452 (10.6%) | |

| South | 2,539 (49.0%) | 437 (46.8%) | 2,102 (49.4%) | |

| West | 740 (14.3%) | 134 (14.4%) | 606 (14.3%) | |

| Unknown | 120 (2.3%) | 14 (1.5%) | 106 (2.5%) | |

| Plan type, n (%) | ||||

| PPO | 3,290 (63.4%) | 589 (63.1%) | 2,701 (63.5%) | 0.539 |

| HMO | 583 (11.2%) | 96 (10.3%) | 487 (11.5%) | |

| POS | 444 (8.6%) | 91 (9.8%) | 353 (8.3%) | |

| Comprehensive | 294 (5.7%) | 56 (6.0%) | 238 (5.6%) | |

| Other or missing | 575 (11.1%) | 101 (10.8%) | 474 (11.2%) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity, n (%) | ||||

| Myocardial infarction | 82 (1.6%) | 15 (1.6%) | 67 (1.6%) | 0.943 |

| Congestive heart failure | 299 (5.8%) | 48 (5.1%) | 251 (5.9%) | 0.369 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 429 (8.3%) | 76 (8.1%) | 353 (8.3%) | 0.877 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 428 (8.3%) | 66 (7.1%) | 362 (8.5%) | 0.148 |

| Dementia | 11 (0.2%) | 1 (0.1%) | 10 (0.2%) | 0.442 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 797 (15.4%) | 128 (13.7%) | 669 (15.7%) | 0.123 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 154 (3%) | 31 (3.3%) | 123 (2.9%) | 0.483 |

| Peptic ulcer | 58 (1.1%) | 8 (0.9%) | 50 (1.2%) | 0.403 |

| Diabetes without complications | 3,598 (69.4%) | 561 (60.1%) | 3,037 (71.4%) | < .001 |

| Diabetes with complications | 2,910 (56.1%) | 416 (44.6%) | 2,494 (58.6%) | < .001 |

| Paralysis | 203 (3.9%) | 35 (3.8%) | 168 (4%) | 0.777 |

| Chronic renal failure | 423 (8.2%) | 61 (6.5%) | 362 (8.5%) | 0.046 |

| Any malignancy, leukemia, lymphoma | 364 (7%) | 78 (8.4%) | 286 (6.7%) | 0.077 |

| Moderate-severe liver disease | 36 (0.7%) | 4 (0.4%) | 32 (0.8%) | 0.281 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 63 (1.2%) | 15 (1.6%) | 48 (1.1%) | 0.226 |

| AIDS | 25 (0.5%) | 1 (0.1%) | 24 (0.6%) | 0.068 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (1.8) | 2 (1.8) | < .001 |

| Median (Q1 to Q3) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | |

| Range | 0, 17 | 0, 12 | 0, 17 | |

| CCI category, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 814 (15.7%) | 214 (22.9%) | 600 (14.1%) | < .001 |

| 1 | 815 (15.7%) | 160 (17.1%) | 655 (15.4%) | |

| 2 | 1,900 (36.6%) | 297 (31.8%) | 1,603 (37.7%) | |

| ≥ 2 | 1,657 (32.0%) | 262 (28.1%) | 1,395 (32.8%) | |

| Pre-index drug use, n (%) | ||||

| Gabapentin | 2,161 (41.7%) | 430 (46.1%) | 1,731 (40.7%) | 0.003 |

| Opioids excluding tramadol | 1,334 (25.7%) | 289 (31.0%) | 1,045 (24.6%) | < .001 |

| Tramadol | 955 (18.4%) | 185 (19.8%) | 770 (18.1%) | 0.219 |

| SNRI | 776 (15.0%) | 161 (17.3%) | 615 (14.5%) | 0.030 |

| TCA | 562 (10.8%) | 122 (13.1%) | 440 (10.4%) | 0.015 |

| Lidocaine | 468 (9.0%) | 95 (10.2%) | 373 (8.8%) | 0.173 |

| BTX | 2 (0.0%) | 0 | 2 (0.1%) | 0.508 |

| Concomitant drug use, n (%) | ||||

| Gabapentin | 312 (6.0%) | 56 (6.0%) | 256 (6.0%) | 0.984 |

| Opioids excluding tramadol | 452 (8.7%) | 91 (9.8%) | 361 (8.5%) | 0.215 |

| Tramadol | 316 (6.1%) | 80 (8.6%) | 236 (5.6%) | < .001 |

| SNRI | 617 (11.9%) | 142 (15.2%) | 475 (11.2%) | < .001 |

| TCA | 307 (5.9%) | 63 (6.8%) | 244 (5.7%) | 0.234 |

| Lidocaine | 127 (2.5%) | 33 (3.5%) | 94 (2.2%) | 0.018 |

| BTX | 1 (0.0%) | 0 | 1 (0.0%) | 0.640 |

| Pre-index HCRU | ||||

| Patients with any hospital admission, n (%) | 1,537 (29.6%) | 304 (32.6%) | 1,233 (29.0%) | 0.030 |

| Number of admissions a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.5) | 0.891 |

| Median (Q1 to Q3) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 2.0) | |

| Range | 1.0, 18.0 | 1.0, 10.0 | 1.0, 18.0 | |

| Length of stay a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 14.7 (24.0) | 14.3 (19.7) | 14.8 (24.9) | 0.271 |

| Median (Q1 to Q3) | 6.0 (3.0, 16.0) | 6.0 (3.0, 17.5) | 6.0 (3.0, 16.0) | |

| Range | 1.0, 256.2 | 1.0, 119.1 | 1.0, 256.2 | |

| Patients with any ER visit, n (%) | 61 (1.2%) | 15 (1.6%) | 46 (1.1%) | 0.177 |

| Number of ER visits a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.739 |

| Median (Q1 to Q3) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0) | |

| Range | 1.0, 3.0 | 1.0, 3.0 | 1.0, 2.0 | |

| Patients with any outpatient visit, n (%) | 5,119 (98.7%) | 914 (98.0%) | 4,205 (98.9%) | 0.026 |

| Number of outpatient visits a | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (13.5) | 16.0 (13.7) | 16.0 (13.4) | 0.682 |

| Median (Q1 to Q3) | 12.0 (7.0, 21.0) | 12.0 (7.0, 21.0) | 12.0 (7.0, 21.0) | |

| Range | 1.0, 155.1 | 1.0, 118.1 | 1.0, 155.1 |

NOTE:

a Annualized statistics among those who had any resource use.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; IQR, inter-quartile range; PPO, preferred provider organization; HMO, health maintenance organization; POS, point-of-service; AIDS, adult immune-deficiency syndrome; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; BTX, botulinum toxin; HCRU, health care resource use.

Study sample

We identified adult patients (≥18 years old) with at least 12 months of continuous enrollment prior to their first pregabalin claim, which was deemed as the index. The 12-month lookback period allowed for baseline data collection while also providing a “washout period” for identifying new pregabalin users. Eligible subjects were also required to have continuous enrollment for at least 12 months after the index pregabalin claim to observe treatment patterns. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

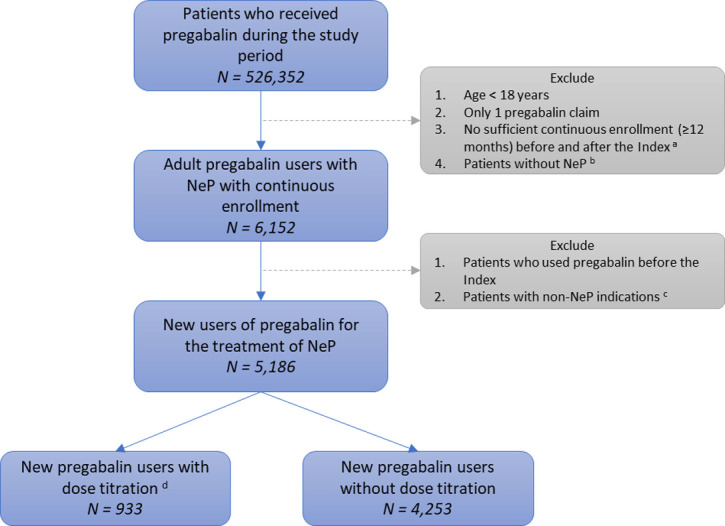

Inclusion criteria (Fig 1):

At least two pregabalin claims during the study period are required within the study period to calculate treatment adherence, AND

Patients with sufficient continuous enrollment (at least 12 months before and after the index pregabalin claim), AND

At least one ICD-9-CM code indicating NeP (Table 2) within 12 months prior to the index pregabalin prescription or within 30 days of index pregabalin prescription, AND

Age ≥18 years at index pregabalin claim.

Flow chart of study sample.

a. Index: first pregabalin claim. b. Neuropathic pain (NeP): diabetic peripheral neuropathy, spinal cord injury, or post-herpetic neuralgia within 12 months prior to or 1 month following the index. c. Non-NeP indications: epilepsy, fibromyalgia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or multiple sclerosis. d. New pregabalin users: no pregabalin use within 12 months prior to the index.

| Criteria | ICD-9-CM | Data Period | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inclusion | |||

| Neuropathic Pain | |||

| Diabetic Peripheral Neuropathy | Diabetes with neurological manifestations | 250.6 | 12 months before index to 30 days after index |

| Polyneuropathy in diabetes | 357.2 | ||

| Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) | Quadriplegia and quadriparesis | 344.0 | |

| Paraplegia | 344.1 | ||

| Cauda equina syndrome | 344.6 | ||

| Fracture of vertebral column with SCI | 806 | ||

| SCI without evidence of spinal bone injury | 952 | ||

| Post-Herpetic Neuralgia | Herpes zoster with other nervous system complications | 053.1 | |

| Exclusion | |||

| Epilepsy | Epilepsy and recurrent seizures | 345 | Any time point |

| Other convulsions | 780.39 | ||

| Fibromyalgia | 729.1 | ||

| Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis | 335.20 | ||

| Multiple Sclerosis | 340 |

Exclusion criteria:

Patients who used pregabalin within 12 months prior to the index claim, OR

Patients who had any diagnosis related to (1) epilepsy, (2) fibromyalgia, (3) amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or (4) multiple sclerosis (Table 2).

Study variables

Dose titration

Pregabalin dose titration was a dichotomous variable, defined as any dose augmentation within 45 days following the index claim.

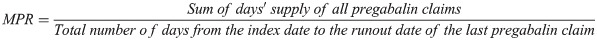

Adherence

The literature reports on a variety of adherence calculation methods based on tablet counts, patient diaries, electronic monitoring by medication containers, and use of adjudicated prescription claims from administrative databases [35]. Of methods not based on patient recall (e.g. diaries), claims-based approaches are clearly the most feasible and least costly to perform on a continuing basis. The current study assessed pregabalin adherence during continuous treatment (i.e. no gap greater than 45 days) using the medication possession ratio (MPR), a ratio of the number of doses dispensed relative to the dispensing period (See formula below). A threshold of 0.8 was used to define adherence.

Treatment switch

We measured treatment switch as non-pregabalin NeP medications (i.e. gabapentin, opioids, SNRI, TCA, lidocaine, and BTX) filled within 45 days following the runout date of a pregabalin claim (i.e., index date + days’ supply).

Persistence

The International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Medication Compliance and Persistence Work Group defined persistence as the number of days taking medication without exceeding permissible gap [35]. In the current study, we measured pregabalin persistence using the time to discontinuation, defined as no pregabalin filled within 45 days following the runout date of a prior pregabalin claim.

Covariates

Covariates included patient demographics (age, sex, geographic region), type of health plan, pre-existing conditions (Charlson comorbidity index), pre-index healthcare resource utilization (hospital admission, inpatient days, outpatient visit, emergency room visit), pre-index medication use (gabapentin, opioids, SNRI, TCA, lidocaine, botulinum toxin), and concomitant use of the above medications following the index claim.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analysis

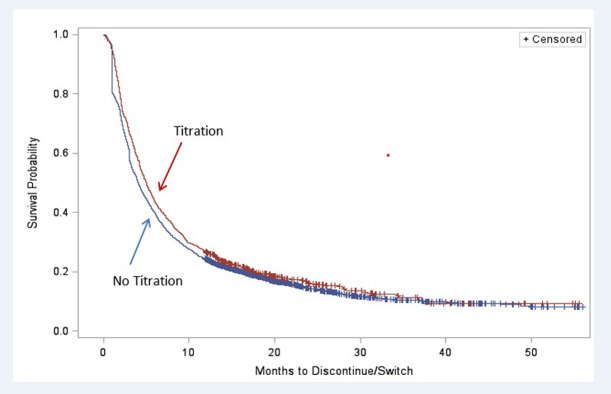

Descriptive analysis was conducted to compare the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics between patients with and without dose titration. For categorical variables (e.g., sex), Pearson chi-square tests were performed to assess statically significant difference; for sub-categories with sample sizes less than 5, Fisher’s exact test was used. For continuous variables, variances were tested using two-groups t-tests or analysis of variance (ANOVA) [36]. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to compare the time to pregabalin discontinuation between patients with and without dose titration [36].

Multivariable analysis

Multivariable logistic regressions were performed to identify factors associated with adherence (MRP ≥ 0.8). Cox proportional hazards models were conducted to identify predictors of time to discontinuation [36].

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.). All variance analyses were 2-sided, and statistical significance was defined at α = 0.05 level.

Results

Study sample

Fig 1 shows the construction of the study sample. A total of 5,186 naïve pregabalin users were included in the study. There were 933 (18.0%) pregabalin users who had dose titration, while the remaining 4,253 (82.0%) pregabalin users did not have any dose augmentation within 45 days following the index claim.

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics were compared by titration status (Table 1). Compared with patients without dose titration, a lower proportion of patients with dose titration had diabetes (with or without complications) or chronic renal failure. Patients who had dose titration tended to have a lower Charlson comorbidity index, with 59.9% of patients having at least two pre-existing conditions, compared with more than 70% among patients who did not have dose titration (P < 0.001). Pre-index use of gabapentin, opioids (excluding tramadol), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) were more frequent among patients with dose titration versus those without dose titration. Concomitant use of tramadol, SNRI, and lidocaine was also more prevalent among patients who had dose titration. A larger proportion of patients with titration had pre-index hospitalization (32.6% vs 29.0%, P = 0.03).

Patterns of dose titration

Among patients with dose titration, the average initial dose was 152 mg/day and the ending dose was 290 mg/day (Table 3), compared with 185 mg/day (P < 0.001) and 180 mg/day (P < 0.001) among patients without dose titration. Overall, approximately 1 in 4 pregabalin users (26.9%) reached 300 mg/day. The proportion of patients receiving at least 300 mg/day of pregabalin was significantly higher among those who had dose titration than those who did not (59.5% vs 19.7%, P < 0.001).

| Variable | Overall N = 5,186 | With pregabalin dose titration N = 933 | Without pregabalin dose titration N = 4,253 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial dose (mg/day) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 179.1 (107.6) | 152.4 (71.9) | 185.0 (113.1) | < .001 |

| Median (IQR) | 150.0 (131.6, 225.0) | 150.0 (100.0, 150.0) | 150.0 (150.0, 225.0) | |

| Range | 25.0, 1000.0 | 25.0, 600.0 | 25.0, 1000.0 | |

| Ending dose (mg/day) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 200.1 (121.5) | 290.4 (133.8) | 180.3 (109.1) | < .001 |

| Median (IQR) | 150.0 (150.0, 300.0) | 300.0 (200.0, 300.0) | 150.0 (120.0, 225.0) | |

| Range | 25.0, 1000.0 | 45.0, 1000.0 | 25.0, 1000.0 | |

| Reaching 300 mg/day, n (%) | 1,394 (26.9%) | 555 (59.5%) | 839 (19.7%) | < .001 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation; IQR, inter-quartile range.

Association between titration and adherence

Patients who had pregabalin dose titration were approximately 2.6 times more likely to be adherent (MPR ≥ 0.8) than those who did not have dose titration [odds ratio (OR) = 2.59, P < 0.001] (Table 4). Other covariates positively associated with being adherent include increased age, male gender, region as north central, pre-index gabapentin use, pre-index TCA use, concomitant lidocaine use, and pre-index inpatient days. Females (OR = 0.76, P < 0.001) and patients with higher CCI (OR = 0.94, P < 0.001) were less likely to be adherent.

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.02 | 1.01, 1.02 | <0.001 |

| Region | |||

| South | Ref | ||

| North Central | 1.24 | 1.08, 1.43 | 0.003 |

| Northeast | 1.15 | 0.96, 1.39 | 0.135 |

| West | 2.06 | 1.40, 3.02 | <0.001 |

| Unknown | 1.16 | 0.98, 1.38 | 0.091 |

| Insurance type | |||

| PPO | Ref | ||

| POS | 0.89 | 0.72, 1.08 | 0.238 |

| HMO | 0.93 | 0.78, 1.12 | 0.455 |

| Comprehensive | 0.97 | 0.75, 1.25 | 0.805 |

| Others or missing | 1.07 | 0.89, 1.29 | 0.455 |

| Gender | |||

| Female vs. Male | 0.76 | 0.67, 0.85 | <0.001 |

| CCI | 0.94 | 0.91, 0.97 | <0.001 |

| Pregabalin dose titration | 2.59 | 2.22, 3.02 | <0.001 |

| Starting Pregabalin dose >150 mg | 1.06 | 0.94, 1.20 | 0.341 |

| Pre-index opioids use (excluding tramadol) | 1.01 | 0.88, 1.16 | 0.893 |

| Pre-index gabapentin use | 1.20 | 1.07, 1.36 | 0.002 |

| Pre-index lidocaine use | 0.90 | 0.74, 1.10 | 0.319 |

| Pre-index TCA use | 1.25 | 1.04, 1.51 | 0.016 |

| Pre-index SNRI use | 1.09 | 0.92, 1.30 | 0.308 |

| Pre-index tramadol use | 0.96 | 0.83, 1.12 | 0.615 |

| Concomitant SNRI use | 0.91 | 0.76, 1.10 | 0.347 |

| Concomitant gabapentin use | 0.88 | 0.69, 1.11 | 0.276 |

| Concomitant opioids use (excluding tramadol) | 1.15 | 0.94, 1.42 | 0.181 |

| Concomitant tramadol use | 1.05 | 0.83, 1.34 | 0.687 |

| Concomitant lidocaine use | 1.50 | 1.03, 2.19 | 0.035 |

| Pre-index number of hospital admissions | 1.02 | 0.95, 1.09 | 0.634 |

| Pre-index number of outpatient visits | 1.00 | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.157 |

| Pre-index number of ER visits | 0.84 | 0.53, 1.32 | 0.450 |

| Pre-index inpatient days | 1.01 | 1.00, 1.01 | 0.004 |

NOTE:

Abbreviation: MPR, medication possession ratio; PPO, preferred provider organization; HMO, health maintenance organization; POS, point-of-service; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; ER, emergency room.

Association between titration and persistence (no switch or discontinuation)

The median time to discontinuation or switch was 5.0 [95% confidence interval (CI): 2.1–13.1] months for those with dose titration, compared with 4.0 (95% CI: 1.9–11.4) months for those without dose titration. Kaplan-Meier analysis (Fig 2) shows that the time to discontinuation or switch was longer among pregabalin users who had dose titration (P = 0.009). The multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards model shows that pregabalin users who had dose titration had greater persistence (i.e., less likely to switch therapy or discontinue pregabalin) than those who did not have dose titration (hazard ratio = 0.91, P = 0.016) (Table 5). Other covariates that were independently associated with greater persistence include: age, male gender, West region, CCI score, pre-index gabapentin use, concomitant SNRI use, concomitant opioid use, and pre-index inpatient days. Pre-index use of tramadol was associated with lower persistence.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of months to pregabalin discontinuation or switch.

| Variable | Hazards Ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.00 | < .001 |

| Region | ||||

| South | ||||

| North Central | 0.93 | 0.86 | 1.00 | 0.055 |

| Northeast | 0.96 | 0.87 | 1.06 | 0.424 |

| West | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.66 | < .001 |

| Unknown | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.93 | 0.001 |

| Insurance type | ||||

| PPO | ||||

| POS | 1.01 | 0.90 | 1.12 | 0.915 |

| HMO | 0.95 | 0.87 | 1.05 | 0.352 |

| Comprehensive | 0.94 | 0.82 | 1.07 | 0.330 |

| Others or missing | 0.90 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 0.042 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female vs. Male | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.28 | < .001 |

| CCI | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.004 |

| Pregabalin dose titration | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.98 | 0.016 |

| Starting Pregabalin dose >150 mg | 0.94 | 0.88 | 1.00 | 0.052 |

| Pre-index opioids use (excluding tramadol) | 1.06 | 0.98 | 1.14 | 0.133 |

| Pre-index gabapentin use | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.91 | < .001 |

| Pre-index lidocaine use | 1.11 | 1.00 | 1.23 | 0.061 |

| Pre-index TCA use | 0.92 | 0.83 | 1.01 | 0.091 |

| Pre-index SNRI use | 0.97 | 0.89 | 1.07 | 0.578 |

| Pre-index tramadol use | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.18 | 0.036 |

| Concomitant SNRI use | 0.69 | 0.62 | 0.76 | < .001 |

| Concomitant gabapentin use | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.12 | 0.796 |

| Concomitant opioids use (excluding tramadol) | 0.81 | 0.72 | 0.90 | < .001 |

| Concomitant tramadol use | 0.65 | 0.57 | 0.75 | < .001 |

| Concomitant lidocaine use | 0.83 | 0.68 | 1.02 | 0.071 |

| Pre-index number of hospital admissions | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.08 | 0.091 |

| Pre-index number of outpatient visits | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.729 |

| Pre-index number of ER visits | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.09 | 0.205 |

| Pre-index inpatient days | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.004 |

NOTE: Treatment discontinuation or switch indicates non-persistence. Therefore, dose titration (bold) is associated with better persistence.

Abbreviation: PPO, preferred provider organization; HMO, health maintenance organization; POS, point-of-service; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; TCA, tricyclic antidepressants; ER, emergency room.

Discussion

The goal of clinical management for NeP is to control pain, given that the condition is currently without a curative option. To achieve better pain relief and adherence, the US prescribing information states that pregabalin should be started at 150 mg/day and titrated to 300 mg/day within one week [29]. However, the current study found that most naïve pregabalin users (82%) did not have dose titration within 45 days following the initial dose. Patients who had dose titration tended to have fewer pre-existing conditions, and received alternative treatment before pregabalin, including gabapentin, opioids, and antidepressants. Consistent with the literature on the relationship between dose titration and greater adherence in other disease populations [22, 23], we found that NeP patients who had pregabalin titrated to the target dose were 2.6 times more likely to be adherent, as measured by MPR. Moreover, dose titration was shown to be an independent predictor of greater persistence, indicating that patients who had dose titration were less likely to switch therapy or discontinue pregabalin treatment. Indeed, our study shows that pregabalin users who had dose titration stayed on the treatment for an average of one month longer than patients who did not have dose titration.

One possible explanation for better adherence and persistence among patients with dose titration is that patients who had dose titration are more likely to achieve optimal therapeutic effect. For example, a study using data from 10 clinical trials on pregabalin in multiple indications found that if patients initiated pregabalin treatment at a lower dose and titrated gradually based on the effectiveness, they would be more likely to continue using pregabalin due to better pain relief [37].

An alternative explanation for better adherence and persistence among patients with dose titration is that dose titration can be a proxy of physician-patient relationship. A study of patients with chronic pain found that physician-patient relationship was significantly associated with treatment adherence and outcomes (e.g. pain control, quality of life) [38]. Intuitively, dose titration would require active monitoring of the treatment effectiveness and thus more physician visits and physician-patient communications. Previous research indicated that physician-patient relationship may reflect levels of satisfaction with care, trust in the physician, and patient participation [38]. Future research is warranted to examine how the physician-patient relationship plays a role in dose titration and treatment adherence.

This study has limitations inherent to retrospective claims database analyses that are noteworthy. One of the limitations is that claims databases do not typically contain information on patient-reported pain outcomes. It is possible that some patients might have enough pain relief at a lower dose of pregabalin and therefore did not need dose titration. Future research with information on pain outcomes will be useful to examine the relationship between titration and treatment outcome. In addition, pregabalin dose is recommended to be reduced for patients with chronic kidney diseases [16]. Therefore, it is possible that a subset of the study sample received lower doses due to impaired renal function rather than titration. Future research would benefit if the reason of reduced dose is available in the data source.

Conclusions

The current study is the first study that examines the effects of dose titration on patient adherence and persistence among patients taking pregabalin for NeP [32]. The positive association between dose titration and treatment adherence that was noted in this study will provide valuable evidence to increase physician awareness of dose recommendations in the prescribing information and to educate patients on the importance of dose titration and adherence and when patients can expect the optimal level of pain relief.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Gavin Lyndon for his input on the study design.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

Effects of dose titration on adherence and treatment duration of pregabalin among patients with neuropathic pain: A MarketScan database study

Effects of dose titration on adherence and treatment duration of pregabalin among patients with neuropathic pain: A MarketScan database study