Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

The TIFY gene family is a plant-specific gene family encoding a group of proteins characterized by its namesake, the conservative TIFY domain and members can be organized into four subfamilies: ZML, TIFY, PPD and JAZ (Jasmonate ZIM-domain protein) by presence of additional conserved domains. The TIFY gene family is intensively explored in several model and agriculturally important crop species and here, yet the composition of the TIFY family of maize has remained unresolved. This study increases the number of maize TIFY family members known by 40%, bringing the total to 47 including 38 JAZ, 5 TIFY, and 4 ZML genes. The majority of the newly identified genes were belonging to the JAZ subfamily, six of which had aberrant TIFY domains, suggesting loss JAZ-JAZ or JAZ-NINJA interactions. Six JAZ genes were found to have truncated Jas domain or an altered degron motif, suggesting resistance to classical JAZ degradation. In addition, seven membranes were found to have an LxLxL-type EAR motif which allows them to recruit TPL/TPP co-repressors directly without association to NINJA. Expression analysis revealed that ZmJAZ14 was specifically expressed in the seeds and ZmJAZ19 and 22 in the anthers, while the majority of other ZmJAZs were generally highly expressed across diverse tissue types. Additionally, ZmJAZ genes were highly responsive to wounding and JA treatment. This study provides a comprehensive update of the maize TIFY/JAZ gene family paving the way for functional, physiological, and ecological analysis.

Introduction

Jasmonates (JAs) are plant oxylipin hormones involved in the regulation of diverse physiological processes in plants, including reproductive development, abiotic stress response, and defense against insect and microbes [1–3]. In plant cells, jasmonates are synthesized from linolenic acid via the octadecanoid pathway [4–6], through the activity of at least eight enzymes (lipase, lipoxygenase, allene oxide synthase and cyclase, 12-OPDA (12-oxophytodienoic acid) reductase, acyl-CoA oxidase, a multifunctional protein, and 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase) [7–9]. JA perception occurs through the interaction of the biologically active ligand, JA-Ile, with SCFCOI1 which results in ubiquitination of the JAZMONATE ZIM-Domain (JAZ) transcriptional repressors that are then targeted for degradation by the 26S proteasome proteolytic pathway [10,11]. The result is derepression of bHLH transcription factors, such as MYC2, allowing activation of JA responsive gene induction [10–12].

JAZs belong to the larger TIFY superfamily [13], previously known as Zinc-finger protein expressed in the inflorescence meristem (ZIM) [14]. The TIFY family members contain the TIFY motif and are grouped into four subfamilies: ZML (ZIM-like), TIFY, PPD, and JAZ based on their domain structure [13,15]. The members of the ZML subfamily contain a TIFY, C2C2-GATA zinc-finger, and CCT domain [16]. Proteins unified with only the TIFY motif belong to the TIFY subfamily [13]. PPD proteins possess three domains: an N-terminal PPD domain, a TIFY domain, and a Jas domain located near the N-terminus [15]. The JAZ subfamily members have two conserved domains: the TIFY domain at the N-terminal with the core sequence TIF [F/Y] XG, and a Jas domain at the C-terminal with a unique sequence SLX2FX2KRX2RX5PY [12,13,17]. Unlike the variable TIFY domain, the sequence of the Jas domain is remarkably conserved among all JAZ subfamily members across different plant species. Many JAZ isoforms are characterized as transcriptional repressors and are commonly associated with co-repressors such as TOPLESS (TPL)/TPL-related proteins (TPPs) that interact with the adaptor protein, NOVEL INTERACTOR OF JAZ (NINJA) [18]. In the absence of JA, the TIFY domain interacts with the C-terminal of NINJA while the Jas domain binds and represses bHLH transcription factors [12,18–20].

In recent years, JAZ proteins have been intensively investigated, primarily for their roles in numerous aspects of plant development and defense responses against biotic and abiotic stresses. Gain-of-function mutations in AtJAZ2 prevent coronatine-mediated stomatal reopening and are highly resistant to Pseudomonas syringae [21]. AtJAZ1, AtJAZ3, and AtJAZ4 interact with APETALA2 transcription factors to repress the transcription of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) [22]. AtJAZ7 negatively regulates dark-induced leaf senescence [23]. Additionally, AtJAZ7, along with AtJAZ8, play a role during defense to fungal infection and insect herbivory [24,25]. AtJAZ1 and AtJAZ10 are among the best understood JAZs owed to their repression of the well-explored JA-responsive transcription factor, AtMYC2 [26,27] and AtJAZ13 has also been found to physically interact with JA-responsive transcriptional factor AtMYC2 [28]. A recent study discovered that JAZ proteins promote growth and reproduction by preventing unnecessary plant immune responses [29].

Most JAZ genes explored thus far are wound- and herbivory-inducible [30]. In rice, overexpression of JAZ genes with a mutated Jas domain such as mOsJAZ3, mOsJAZ6, mOsJAZ7, and mOsJAZ11 affect spikelet development and have wide-spread pleiotropic effects [31]. The overexpression of OsJAZ9 increases tolerance to salt and drought [32]. In tomato, several JAZ genes are inducible by pharmacological application of JA and abscisic acid (ABA) and SlJAZ3, SlJAZ7, and SlJAZ10 in particular are induced in leaves following salt treatment [33]. Together, these studies provide convincing evidence highlighting the importance of JAZ proteins in plant development, growth, and defense.

In recent years, the genomes of many plant species have been surveyed to catalogue their TIFY/JAZ genes. In Arabidopsis, 19 members constitute the TIFY family which includes two ZML, two PPD, two TIFY and 13 JAZ genes [15,28,30,34]. Comparative analysis of other plant species found variability in their TIFY genes content with Arabidopsis [13,28], tomato [33], Asian cotton [35], Brachypodium distachyon [36], Chinese pear [37], grape [38], Brassica napus [39], rice [32], maize [15,40–42], and wheat [43] containing 19, 19, 21, 21, 22, 19, 36, 20, 30, and 47 TIFY members, respectively. In these species, JAZs account for about 66% of TIFY family [15]. Interestingly, in the monocotyledonous species no PPD proteins have been identified so far [15]. In maize, the literature has yet to reach an agreement over the accurate number of total TIFY genes where as little as 27 to as high as 48 were reported [15,40–42]. In 2016, the maize reference genome was updated using single-molecule sequencing technology to Zm-B73-REFERENCE-GRAMENE-4.0 (also known as "B73 RefGen_v4" or "AGPv4") which is substantially different from the previous AGPv3. In this study, we utilized version 4 of the maize reference genome to update the list of TIFY genes and classified them into subfamilies based on the presence of their respective conservative domains. To provide insights into the functions of different family members, the expression of all the ZmTIFY genes were assessed in various tissues and organs at different developmental stages and in response to wounding and JA chemical treatment. In addition, the promoters of ZmTIFY genes were analyzed for predicted cis-elements that may explain potential conditional-dependent gene induction.

Materials and methods

Plant material

The maize inbred B73 was used as the plant material for this study. The seeds were sowed in plastic boxes containing a soil mix of vermiculite: organic substrate: loam (1:1:1 v/v/v). The seedlings were grown in a greenhouse at 25–35 C with relative humidity maintained at 60%-85% and illuminated by natural sunlight. The experiments were carried out in the seasons of Spring or Autumn when the average photoperiods were approximate 12 h-day/12 h-night.

Mechanical wounding and JA treatment

The mechanical wounding treatment was conducted as described by [44]. The second leaf of a V3 stage plants was squeezed with pliers twice on each side of the midrib about 1cm apart without damaging to the midrib. The undamaged midsection flanked by the two wound sites was collected at 0, 1, 3, 6 h post-wounding and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C for downstream analysis.

Seedlings at the V3 stage were sprayed with 100μM of JA solution or water as control until both sides of the leaves were completely wet and collected at 0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after chemical treatment, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at -80°C until further analysis. Three biological replicates were collected per time-point for each treatment-group.

Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol according to the manufacturer’s instructions and its integrity was tested on a 1% agarose gel by visualizing defined 16S and 18S rRNA bands. Genomic DNA was removed according to GoldenstarTM RT6 cDNA synthesis kit (Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd at Shanghai). For reverse transcription, 2 μg of total RNA was used to generate cDNA through the GoldenstarTM RT6 cDNA synthesis kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cDNA synthesis reactions consisted of 2μl (~2μg) of RNA template, 4μl of GoldenstarTM RT6 cDNA synthesis mix, and 14μl of RNase-free water followed with incubation at 50°C for 30 minutes and then at 85°C for 10 minutes.

Expression analysis was conducted with semi-quantitative real-time PCR using primers designed to selectively amplify distinct JAZs (S3 Table) and EIF4A gene was used as the house-keeping gene control for equal loading of cDNA. The reaction consisted of 12.5μl of 2xTaq PCR master mix (Sangon Biotech Co. Ltd at Shanghai), 1 μl forward primer (10μM), 1μl reverse primer (10μM), 1 μl (100 ng) of cDNA and ddH2O to a final volume of 25μl. Thermal cycling conditions were: 94°C for 4 mins; 94°C for 30 s, 57–58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s, a final incubation at 72°C for 10 min, and depending on reaction, 28–30 cycles were performed. The PCR products were separated and visualized by gel electrophoresis on a 2% agarose gel.

Identification of the maize TIFY gene family and domain analysis

To identify the members of the TIFY family in maize, BLASTP searches were performed on the maize genome database (B73 RefGen_v4, https://maizegdb.org/) using the amino acid (AA) sequences of TIFY and Jas domains from TIFY proteins from Arabidopsis and rice as the search queries. Maize TIFY candidate genes were selected based on the criteria of 50% or greater AA identity and an e-value of 1e-4 or less. To determine the presence of the canonical TIFY subfamily domains, the predicted AA sequences of the ZmTIFY genes were submitted to the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/). For the analysis of the presence of an EAR (ERF-associated amphiphilic repression) motif, candidate proteins were manually compared to the previously reported 158 LxLxL-types of EAR motifs [45].

Tissue-specific expression profiling

RNA-Seq data for tissue-specific expression in 79 tissues [46] were obtained from maizegdb.org. The expression heatmap for tissue-specific expression was created by the software HemI 1.0 [47] using log2 value of FPKM (fragment per kilobase per million mapped reads) of ZmTIFY genes.

Phylogenetic analysis of TIFY genes

A multiple protein sequence alignment was performed for the TIFY family members of Arabidopsis, maize, and sorghum using the online software MUSCLE (www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/muscle/). The phylogenetic tree for all identified TIFY family genes in this study and for all known JAZ genes in Arabidopsis and sorghum were generated with the MEGA 7.0 software using the maximum likelihood method and robustness tested by bootstrapping for 1000 times. The tree was displayed using the online software Evolview v3 [48].

cis-element identification in promoters of TIFY genes

To analyze the putative cis-acting elements of the promoters of the ZmJAZ genes, 1.5 kb of nucleotide sequence upstream of the start codon for each ZmJAZ gene was scanned in the PlantCARE database (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/).

Results

The maize genome houses 47 bona fide TIFY family members including 16 newly identified members

To identify all TIFY genes in the maize genome, the B73 RefGen_v4 genome was surveyed by BLASTP for similar sequences to the AA sequences of the TIFY and Jas domains from the Arabidopsis and rice TIFY proteins. This analysis revealed 47 distinct gene models whose predicted proteins contain a TIFY or Jas domain (Tables 1 and S1). Among these, four were predicted to belong to the ZML subfamily and contained a TIFY, CCT, and GATA zinc finger domain, but no Jas domain. Five of 47 were predicted to belong to the TIFY subfamily which contains solely the TIFY domain (Tables 1 and S1). No PPD proteins were identified. The remaining 38 TIFY proteins were characterized as JAZ proteins, six of which had no TIFY domain at the N-terminus, but all had a Jas domain at the C-terminus (Tables 1 and S1). In total, 38 JAZ, 4 ZML, 5 TIFY-subfamily, and no PPD genes were identified in the maize genome B73 RefGen_v4. Among the 47 TIFY genes, nearly 40% have never been identified in previous analyses of the maize TIFY family. These 16 genes include 13 ZmJAZs, two ZmTIFYs and one ZmZMLs (Tables 1 and S1).

| Locus ID in (V4) | Locus ID in (V3) | Chromosomal Location (V4) | Gene Name a | Gene Name b | Transcript Length (bp, V4) | Protein Length (aa, V4) | TIFY motif c | Jas Domain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zm00001d027899 | GRMZM2G343157 | 1:17141137 | zim26 | ZmJAZ1 | 495 | 164 | TILYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d027901 | GRMZM2G445634 | 1:17156322 | zim16 | ZmJAZ2 | 546 | 181 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d029448 | GRMZM2G117513 | 1:71161670 | zim24 | ZmJAZ3 | 687 | 228 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d033048 | GRMZM2G024680 | 1:248467942 | zim21 | ZmJAZ4 | 651 | 216 | TIFYQG | Yes |

| Zm00001d033050 | GRMZM2G145412 | 1:248529926 | zim18 | ZmJAZ5 | 549 | 182 | TIVYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d033049 | GRMZM2G145458 | 1:248522876 | zim3 | ZmJAZ6 | 489 | 162 | TISYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d034536 | GRMZM2G382794 | 1:295853517 | zim19 | ZmJAZ7 | 357 | 176 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d002029 | GRMZM2G086920 | 2:4666311 | zim32 | ZmJAZ8 | 558 | 216 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d003903 | GRMZM2G145407 | 2:66485018 | zim33 | ZmJAZ9 | 543 | 180 | TVFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d004277 | GRMZM2G171830 | 2:99601657 | zim8 | ZmJAZ10 | 297 | 134 | TIFYDG | Yes |

| Zm00001d005813 | GRMZM2G005954 | 2:189505960 | zim13 | ZmJAZ11 | 531 | 227 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d006860 | GRMZM2G101769 | 2:218018545 | zim12 | ZmJAZ12 | 744 | 237 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d050365 | GRMZM2G151519 | 4:83772143 | zim35 | ZmJAZ13 | 1281 | 426 | TIFYNG | Yes |

| Zm00001d014249 | GRMZM2G064775 | 5:38005178 | zim29 | ZmJAZ14 | 657 | 218 | TIFYQG | Yes |

| Zm00001d014253 | GRMZM2G173596 | 5:38196209 | zim10 | ZmJAZ15 | 483 | 160 | IIVYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d035382 | GRMZM2G338829 | 6:23840275 | zim9 | ZmJAZ16 | 507 | 110 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d020409 | GRMZM2G126507 | 7:112014245 | zim1 | ZmJAZ17 | 1215 | 404 | TIFYAG | Yes |

| Zm00001d020614 | GRMZM2G116614 | 7:125133740 | zim28 | ZmJAZ18 | 657 | 218 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d021274 | GRMZM2G066020 | 7: 147534788 | zim31 | ZmJAZ19 | 657 | 267 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d022139 | GRMZM2G089736 | 7:171049645 | zim23 | ZmJAZ20 | 702 | 233 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d048263 | GRMZM2G036351 | 9:153418013 | zim4 | ZmJAZ21 | 519 | 172 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d048268 | GRMZM2G036288 | 9:153485703 | zim14 | ZmJAZ22 | 552 | 183 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d026477 | GRMZM2G143402 | 10:146705762 | zim34 | ZmJAZ23 | 693 | 207 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d009438 | GRMZM2G054689 | 8:64583138 | zim5 | ZmJAZ24 | 507 | 253 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d013855 | GRMZM2G063632 | 5:22766950 | zim7 | ZmJAZ25 | 669 | 155 | LQFSMV | Yes |

| Zm00001d005726 | GRMZM2G114681 | 2:184842614 | zim15 | ZmJAZ26 | 1620 | 353 | TIFYAG | Yes |

| Zm00001d027900 | GRMZM5G838098 | 4:1:17147073 | zim27 | ZmJAZ27 | 609 | 195 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d014250 | AC197764.4_FG003 | 5:38073928 | zim30 | ZmJAZ28 | 555 | 184 | TLSIFY | Yes |

| Zm00001d016316 | NO | 5:156926728 | zim37 | ZmJAZ29 | 474 | 157 | NO | Yes |

| Zm00001d019692 | NO | 7:51184119 | zim38 | ZmJAZ30 | 1353 | 98 | NO | Yes |

| Zm00001d021924 | NO | 7:165961049 | zim39 | ZmJAZ31 | 414 | 137 | NO | Yes |

| Zm00001d024455 | GRMZM2G442458 | 10:71687709 | zim40 | ZmJAZ32 | 183 | 60 | NO | Yes |

| Zm00001d033972 | NO | 1:279900021 | zim41 | ZmJAZ33 | 502 | 173 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d041045 | NO | 3:92630179 | zim42 | ZmJAZ34 | 621 | 206 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d044708 | NO | 3:235521147 | zim43 | ZmJAZ35 | 453 | 150 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d046270 | NO | 9:77365055 | zim44 | ZmJAZ36 | 414 | 137 | NO | Yes |

| NO | GRMZM2G327263 | 3:231288810(V3) | zim17 | ZmJAZ37 | 4815 | 1604 | TIFYGG | Yes |

| Zm00001d037082 | GRMZM2G314145 | 6:111655145 | zim25 | ZmJAZ38 | 1000 | 135 | NO | Yes |

| Zm00001d028313 | GRMZM2G110131 | 1:30342336 | zim22 | ZmTIFY1 | 381 | 215 | TIFYGG | NO |

| Zm00001d004173 | NO | 2:89164906 | zim45 | ZmTIFY2 | 639 | 212 | TIFYGG | NO |

| Zm00001d051615 | GRMZM2G022514 | 4:164594515 | zim46 | ZmTIFY3 | 3306 | 1101 | TIFYGG | NO |

| NO | GRMZM2G036349 | 9:150516983(V3) | zim6 | ZmTIFY4 | 411 | 136 | NO | NO |

| NO | GRMZM2G122160 | 4:11372450(V3) | zim11 | ZmTIFY5 | 1024 | 197 | TIFYGG | NO |

| Zm00001d013331 | GRMZM2G065896 | 5:8803187 | zim2 | ZmZML1 | 837 | 278 | TLVYQG | NO |

| Zm00001d014656 | GRMZM2G058479 | 5:57723133 | zim36 | ZmZML2 | 882 | 357 | TLSFQG | NO |

| Zm00001d036494 | GRMZM2G080509 | 6:90506221 | zim20 | ZmZML3 | 1077 | 357 | TLSFQG | NO |

| Zm00001d033523 | NO | 1:265546924 | zim47 | ZmZML4 | 867 | 288 | TLVFQG | NO |

a The official names designated by maizeGDB and it is applied in Grassius project [40].

b The gene names in bold are the newly found TIFY genes in this study using B73 RefGen_V4.

c Six TIFY genes have no typical TIFY domain but include Jas motif. The TIFY motif of ZmJAZ25 was largely altered, and ZmTIFY4 lacks TIFY domain and Jas motif.

JAZ proteins are asymmetrically distributed between the two maize subgenomes

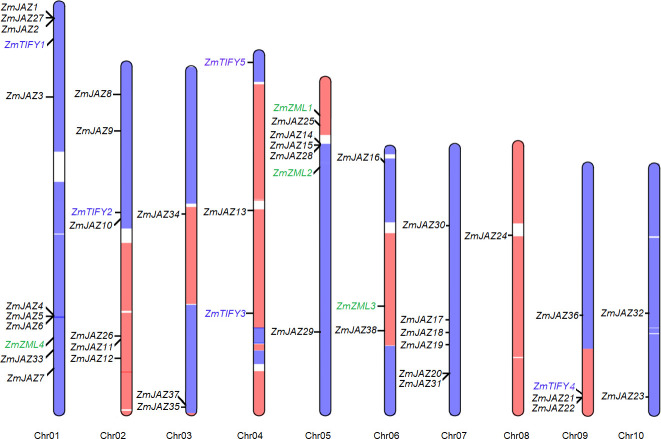

The 47 TIFY genes were found differentially distributed across the ten maize chromosomes. The four ZML genes were located on the chromosome 1, 5, and 6 and the five TIFY-subfamily genes were found on chromosome 1, 2, 4, and 9. The remaining 38 JAZ genes were found on distributed across all ten chromosomes (Fig 1; Table 1). Chromosome 1 was found to contain nine JAZ genes, six of which were clustered in two loci: ZmJAZ1, 2, and 27 and ZmJAZ4, 5, and 6. ZmJAZ14, 15, and 26 were clustered at the short arm of Chromosome 5. Maize is a paleopolyploid plant, which harbors two subgenomes (maize1 and maize2) where each constitutes a genome orthologous to the entire sorghum genome [49]. Interestingly, 32 TIFY genes were found in the maize1, 14 in the maize2, and only one in the region between the two subgenomes (Fig 1) compared to the 19 SbTIFY genes thus so far predicted in the sorghum genome [15].

Distribution of the ZmTIFY genes on maize chromosomes.

The blue and orange regions denote the subgenome1 (maize1) and subgenome2 (maize2) of maize genome (Schnable et al., 2011) and the newly found TIFY genes are highlighted in blue.

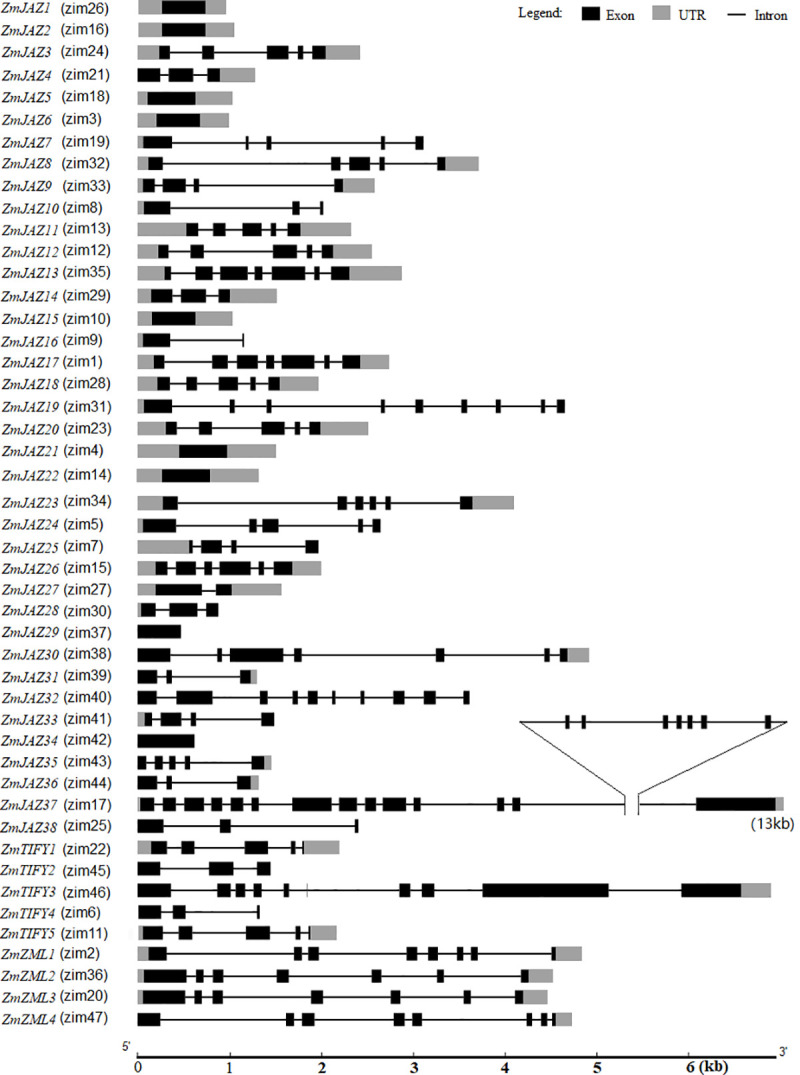

The maize TIFY gene family members possess considerable variability in gene size, structure, and predicted transcript variants

The maize TIFY genes ranged from 474 bp (ZmJAZ29) to 13091 bp (ZmJAZ37) (S1 Document). Gene structural analysis of the TIFY family found that approximately 20% of the members (ZmJAZ1, 2, 5, 6, 15, 21, 22, 29, and 34) were comprised of a single exon and nearly 80% of TIFYs contained two to twenty one exons (Fig 2). Among the 29 JAZs with multiple exons, ZmJAZ37 (v3) is a longest gene with 13091 nucleotides and 21 exons. This gene was remodeled in AGPv4 and AGPv5. The latest gene model of ZmJAZ37 (Zm00001e020904) is only 1476-bp long containing 4 exons (S1 Document). ZmJAZ19 had nine exons and ZmJAZ13 and 17 each had seven exons. Eight ZmJAZs (ZmJAZ3, 8, 11, 12, 18, 20, 24, and 35), three ZmJAZs (ZmJAZ9, 25, and 33), six ZmJAZs (ZmJAZ 14, 28, 30, 31, 36 and 38), and four ZmJAZs (ZmJAZ4, 16, 27, and 32) contained five, four, three, and two exons, respectively (Fig 2). The members of the TIFY subfamily contained between 3 to 10 exons and the ZML subfamily members contained either seven or eight exons (Fig 2).

The genetic structure of the maize TIFY genes.

Scale bar indicates gene size.

The maize TIFY genes were predicted to have varied numbers of transcripts variants (S1 Table). Over 60% or 31 TIFY genes (ZmJAZ1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 14, 15, 16, 19, 21, 22, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 31, 32, 34, 35, 36, 37 and 38, ZmTIFY1, ZmTIFY2, ZmTIFY4, ZmTIFY5 and ZmZML1) have a single transcript (S1 Table) while the other 16 TIFY genes have two to eight transcripts. It is worthy to note that ZmJAZ23 and ZmZML2 have seven and eight predicted transcript variants, respectively (S1 Table).

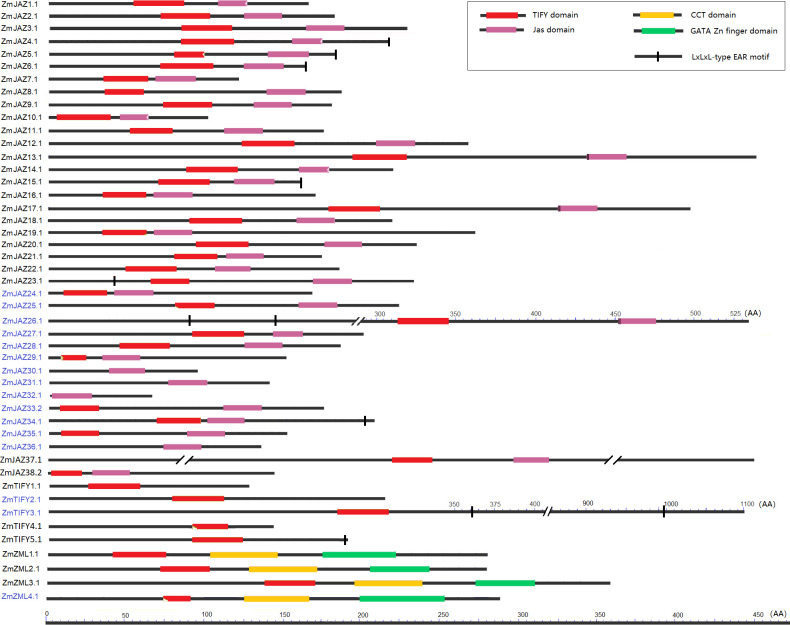

Conserved protein domains and their features different across the maize TIFY family

All ZmTIFY genes are predicted to encode at least one protein which range in sizes from 60 AA to 1604 AA, however the vast majority of TIFY proteins are smaller than 300 AA (S1 Table). The candidate maize TIFY proteins were analyzed for their TIFY and Jas domain compositions along with screening for presence of EAR-motifs. The TIFY domain, also known as the ZIM domain, mediates homo- and heteromeric interactions between JAZ proteins [17,50] and it is necessary for binding to the NINJA–TPL repressor complex [18]. The C-terminal Jas domain is essential for the interaction of JAZ proteins [12] with the LRR domain of JA receptor, COI1 protein [51]. The EAR (ERF-associated amphiphilic repression) motif is a principle mechanism of plant gene regulation and facilitates recruitment of TPL for transcriptional repression [24]. The analysis revealed that all but seven TIFY proteins contained both the TIFY and the Jas domains. The TIFY motif was absent in ZmJAZ 29, 30, 31, 32, and 36, and while it was truncated in ZmJAZ25 and ZmZML4 (S1 Table; Fig 3). JAZ4, 10, and 14 had incomplete Jas domains (S1 Table) and lacked the X5PY. X5PY motif required for JAZ degradation via 26S proteasome [12]. The Jas domains of ZmJAZ13, 17, and 26 had VPQAR in place of the normal LPIAR degron motif the sequence signal required for JAZ repressor degredation [24]. Manual sequence analysis uncovered that seven ZmJAZs (ZmJAZ4, 5, 6, 15, 23, 26 and 34) along with ZmTIFY3 and 5 possessed the LxLxL-type EAR motif (Fig 3).

Conserved domain analysis of the maize JAZ, TIFY and ZML subfamily proteins.

Each domain is represented by a colored box and black lines represented the non-conserved sequences. Scale bar represents peptide length.

In summary, among 38 JAZ proteins, 13 (ZmJAZ4, 10, 13, 14, 17, 25, 26, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34 and 36) had an altered or impaired TIFY or Jas domain. The five TIFY subfamily proteins (ZmTIFY1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) have showed typical TIFY domain sequences. Three of the four maize ZML proteins (ZmZML1, 2, and 3) have an intact TIFY domain, a CCT domain and a GATA zinc finger domain, however the newly identified ZmZML4 bears a truncated TIFY domain.

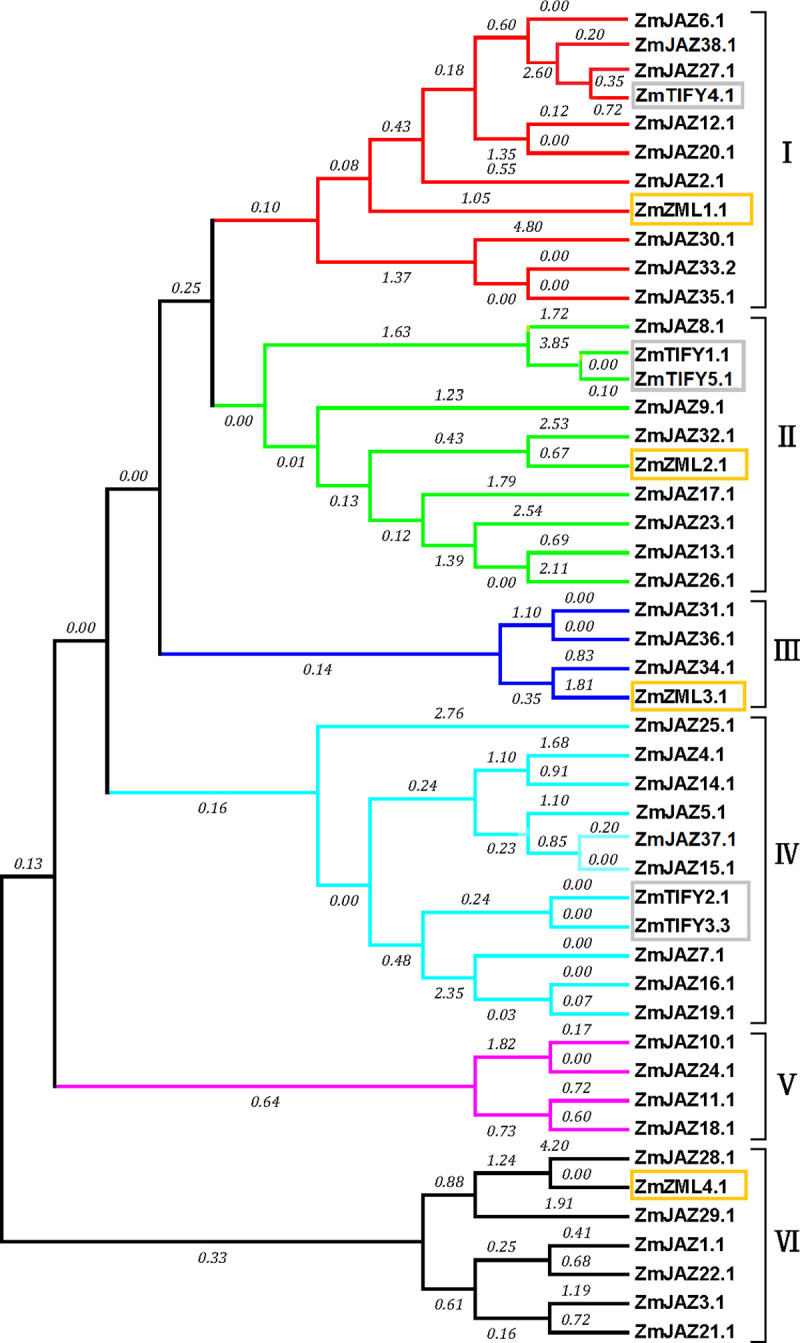

The maize TIFY family members cluster into six distinct clades

To understand the evolutionary relationship of TIFY genes in maize, a phylogenetic tree of ZmTIFY proteins was created by the software Mega7 using the maximum likelihood method. The phylogenetic tree showed that all the TIFY proteins in maize clustered into six clades (Fig 4). Interestingly, ZmTIFY1 and 5 clustered with ZmJAZ8, 9, 13, 17, 23, 26, 32 in clade II (Fig 4) while ZmTIFY2 and 3 clustered with ZmJAZ 4, 5, 7, 14, 15, 16, 19, 25 and 37 in clade IV (Fig 4) and the four ZmZML proteins clustered into separate clades (I, II, II, and VI) (Fig 4). Comparison of maize JAZ proteins with orthologues from Arabidopsis and sorghum found seven clear groups formed with Arabidopsis JAZ proteins clustered into four groups: G1, G3, G4, G5 and G7 while JAZ proteins in maize and sorghum clustered into 6 groups: G2 to G7 (S1 Fig).

Phylogenetic analysis of maize JAZ, TIFY and ZML subfamily proteins.

The phylogenetic tree was constructed in software Mega7 by the maximum likelihood method with the bootstrap test of 1000 replicates. Amino acid sequences were aligned with Muscle (Multiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation).

All maize JAZ promoters contain JA responsive regulatory elements

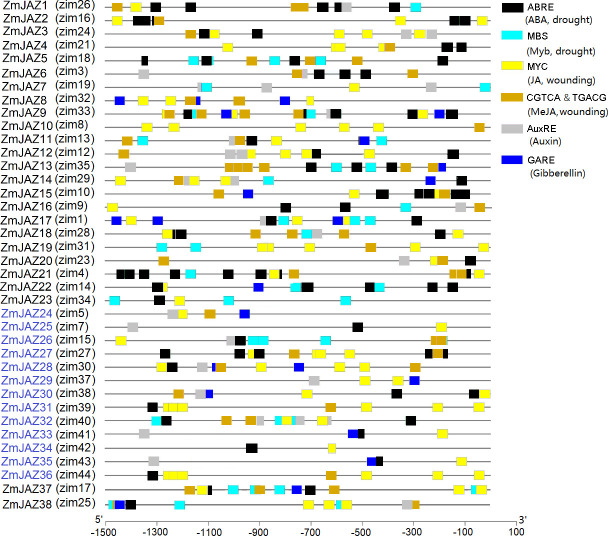

Promoter sequences of the ZmJAZ genes were analyzed via the PlantCARE database to identify cis-regulatory elements in the1.5kb promoter segment upstream of their start codons. Attention was given to elements relevant to hormone and stresses responses (Fig 5; S2 Table). Those elements included: (1) the ABRE motif, involved in abscisic acid (ABA) responses; (2) MBS, a MYB transcriptional factor binding site involved in drought tolerance; (3) MYC, a transcriptional factor of JA responsive genes; (4) the CGTCA- and TGACG-motifs, involved in methyl-JA acid (MeJA) responses; (5) the AuxRR-core, TGA-element, and AuxRE, the auxin-responsive elements; and, (6) the GARE-motif and TATC-box, that serve as gibberellin (GA) -responsive elements.

cis-regulatory elements identified in the 1.5 kb-promoter regions of ZmJAZ genes.

Different colored boxes denote different type of cis-regulatory elements and labeled according to legend. The scale bar indicates the location of each cis-elements within the promoters.

All putative ZmJAZ promoters contained at least two different regulatory elements (Fig 5) with some, such as ZmJAZ9, possessing all six elements of the analysis. All ZmJAZ promoters contained either MYC-binding site or CGTCA/TGACG–motif for JA and MeJA responses, respetively (Fig 5). Most ZmJAZ promoters contained one to several ABRE motifs are involved in abscisic acid (ABA) responsiveness (Fig 5).

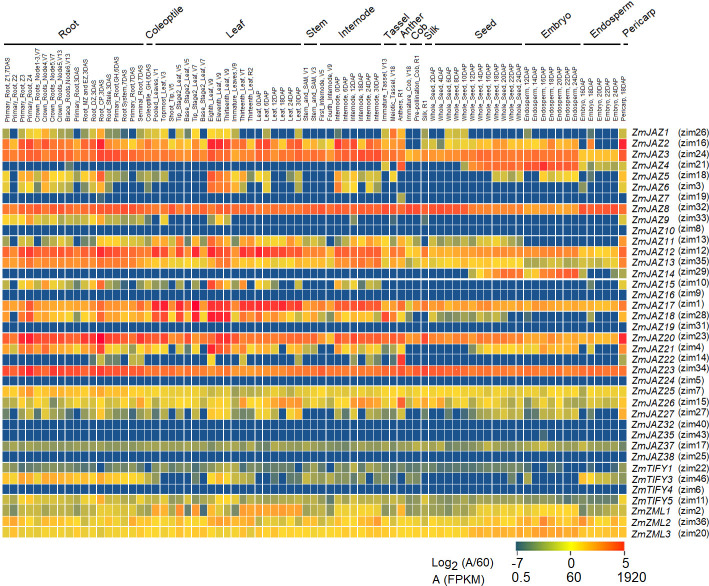

Most ZmJAZ genes have non-specific expression across maize tissues under basal conditions

To gain insight into tissue-specific expression of the maize TIFY genes, publicly available transcriptomes of 79 different maize tissues and organs [46] were mined. Of the 43 genes identified in our study, 34 TIFY genes were found transcribed at basal levels in at least one of the available tissue types (Fig 6) and several patterns emerged.

Heatmap of expression patterns for maize TIFY genes in 79 tissues.

The heatmap was generated using log2 (abundance/60) in which red color indicates high expression and blue indicates low expression.

Generally, most TIFY genes were found to be expressed in most tissue types, albeit at varying levels of expression. Eight (ZmJAZ2, 3, 8, 11, 12, 13, 26 and 27) were found highly expressed (transcript abundance >60 FPKM) and five (ZmJAZ17, 25, ZmZML1, 2, 3) were medium-expressed (1<transcript abundance<60 FPKM) across all tissues. (Figs 6 and S2). Seven TIFY genes (ZmJAZ4, 5, 6, 14, 15, 18, and 21) were high-expressed but in a limited number of tissue types. Interestingly, tissue specificity was found for three JAZ genes; ZmJAZ14 was found to be seed-specific and ZmJAZ19 and 22 were only found expressed in the anthers (Figs 6 and S2). Expression of ZmJAZ4 and JAZ7 was prominent in seed and anther, respectively, but they also displayed low expression across other tissues. ZmJAZ7, 9, 10, 16, 24, 32, 35, 37, 38, ZmTIFY1, 3, 4 and 5 were low-expressed genes (transcript abundance < 1 FPKM) in all maize tissues tested under these conditions.

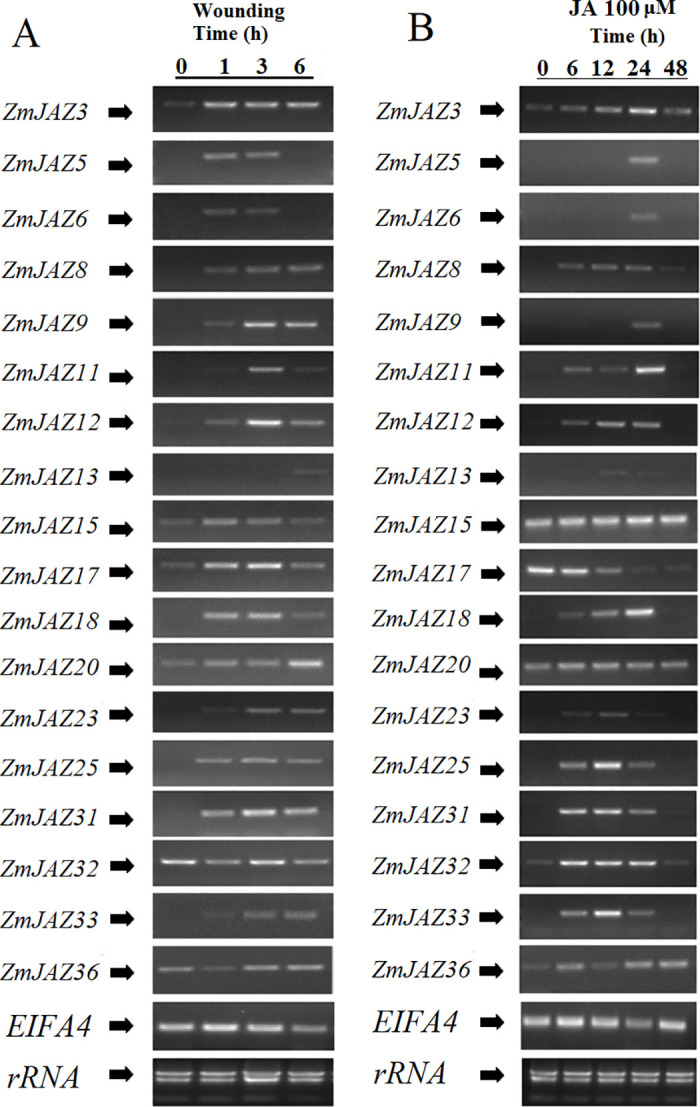

Expression patterns of ZmJAZ genes in response to wounding and JA treatment

To understand the inducibility of ZmJAZs during defense responses, we measured transcript accumulation of the gene expression in the second leaves of maize seedlings following mechanical wounding or chemical application. Expression of 18 ZmJAZ genes (ZmJAZ3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 23, 25, 31, 32, 33, and 36) were detected in these experiments.

Apart from ZmJAZ32 and 36, all ZmJAZ genes tested were found to be transiently induced by wounding. ZmJAZ5, 6, 15, and 17 displayed a rapid, but short, increase in wound-inducible expression; induction of these genes was detected at 1 and 3 h post-wounding, but subsided by 6 h. Wounding induced expression of ZmJAZ3, 8, 9, 12, 18, 25, 31, and 33 as early at 1 h following treatment, but their induction persisted for the duration of the time-course. ZmJAZ13, 20, and 23 appear to be late wound-induced genes and it is likely their peak of their expression was not captured within the time-points tested (Fig 7A).

Transcription activation of ZmJAZ genes upon wounding treatment (A) or 100μM JA treatment (B). Semi-qPCR was conducted to quantify the expression level of the JAZ genes. The EIF4A gene was employed as the reference gene.

Mechanical damage induces production of JA and subsequent JA-responsive gene expression. To test the contribution of JA in wound-inducibility of ZmJAZ genes, maize seedlings were chemically treated with JA. With the exception of ZmJAZ15, 17, and 20, most maize JAZ genes were found to be JA-inducible. Expression of ZmJAZ8, 11, 12, 18, 25, 31, 32, and 33 were induced as early as 6 h and persisted for at least 24 h after treatment. Transcription of ZmJAZ5, 6, and 9 was detected at only 24 hours post wounding. ZmJAZ15 and ZmJAZ20 were constitutively expressed in the leaves and unresponsive to JA treatment and remarkably, ZmJAZ17, the most highly expressed gene in the leaves (Fig 6), was the only ZmJAZ observed to be repressed by JA treatment (Fig 7B).

Comparison of expression patterns between mechanically wounded and JA treated plants found that the majority of ZmJAZ genes induced by mechanical damage were also JA-responsive. Interestingly, several genes responded differently to JA treatment and wounding in the time-points measured. Wounding, but not JA-treatment, induced ZmJAZ15 and 20, however the opposite was observed for ZmJAZ32 (Fig 7).

Discussion

In recent years, advances in sequencing technologies have enabled substantial improvements to the maize reference genome providing a more accurate representation of the genomic composition and subsequent gene models. In this study, we used updated B73 reference genome AGPv4 to identify and categorize 47 TIFY family genes, named ZmZIM1 to ZmZIM47 (Table 1). This work augments the existing literature with over 40% more maize TIFY members, compared with previous studies that identified only up to 30 isoforms [15,40–42]. More specificially, our analyisis uncovered five, four, and 38 genes to the TIFY, ZML, and JAZ subfamilies, respectively and were named accordingly. No PDD subfamily members were identified during this process, consistent with what is currently understood from other monocot species [15,41]. Compared with other grasses, the maize genome encodes more than twice the number of predicted TIFY genes than Brachypodium [36], rice [32], or sorghum [15], and thus far only wheat is known to contain more with 47 identified.

Maize arose from a hybridization of two ancestral species that produced an allotetraploid approximately 14 million years ago and soon after underwent diploidization [52] resulting in a segmental alleotetraploid [53]. The closest crop species relative to maize is sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) which diverged from one of the maize ancestors around the same time of the maize hybridization event. Using the sorghum genome as a guide, segments from the two maize subgenomes (maize1 and maize2) can be differentiated where each subgenome is orthologous to the sorghum genome [49]. In our analysis, 32 and 14 TIFY genes were identified on the maize1 and maize2 genomes, respectively (Fig 1). This observation agrees with the finding that in modern maize inbred lines, maize2 has exhibited significantly more gene loss compared to maize1 [49].

Prior to the discovery of JAZ proteins [10,12,33], the functional annotation of the plant-specific TIFY family was unclear [13]. [15] analyzed the origin and evolution of the TIFY genes and organized them into four subfamilies: ZML, TIFY, PPD and JAZ where the latter can account for 60–80% of the TIFY genes in a species and undeniably are the best understood. In Arabidopsis, JAZ proteins are transcriptional repressors for JA-mediated response [10–12]. During JA signaling, JA-Ile serves as a ligand to promote the formation of a SCFCOI1-JA-Ile-JAZ complex in which JAZ proteins are ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by the 26S proteasome [10,11].

JAZ proteins contain a TIFY and Jas domain in their N- and C-terminus, respectively, and both domains are required during JA signal transduction. The TIFY domain is necessary for homo- and heteromeric dimerization between the TIFY family members [50] and for JAZ-NINJA-TPL interaction and the Jas domain is required for the formation of the COI1–JAZ co-receptor complex [51]. In maize, five TIFY subfamily proteins (ZmTIFY1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) contain solely a TIFY domain (S1 Table; Fig 3), however they are highly similar with typical ZmJAZ proteins and cluster with them during phylogenetic analysis (Fig 4). These observations suggest that the maize TIFY subfamily are comprised of JAZ proteins that have lost their Jas domains during the evolutionary process. In contrast, several ZmJAZ proteins possessed normal Jas domains but either lacked (ZmJAZ 29, 30, 31, 32, and 36) or have incomplete (ZmJAZ25 and ZML4) TIFY domains (S1 Table; Fig 3), which likely results in the inability to dimerize normally with other JAZ proteins and the subsequent loss of function as transcriptional repressors.

In terms of the Jas domain, most ZmJAZ proteins were predicted to contain intact sequences (S1 Table), however several isoforms either had an incomplete (ZmJAZ4, 10, and 14) domain lacking the motif “XXPY” or had an altered degron motif (ZmJAZ13, 17, and 26) where the typical “LPIAR” motif was replaced by “VPQAR”. In Arabidopsis, five JAZ genes encode different transcript variants [12] with AtJAZ10 having up to four, correspondingly to the protein isoforms, AtJAZ10.1, 10.2, 10.3, and 10.4 [17]. AtJAZ10.3 has a truncated Jas domain missing the “XXPY” motif and AtJAZ10.4 has completely lost Jas domain [12,17]. Loss of normal Jas domain is associated with increased stability during JA signaling process and overexpression of these isoform variants perturb normal JA responses [12,17]. In maize, 14 JAZ genes (ZmJAZ3, 8, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 20, 23, 25, 26, 27, 30, and 33) have two to seven alternative transcripts, and with several variants missing either TIFY or Jas domain or both (S1 Table). Notably, ZmJAZ23 showed parallels with AtJAZ10 in that it encodes several transcript variants, some which produce typical JAZ proteins (ZmJAZ23.1, 23.2, 23.3, and 23.4) and others are either missing (ZmJAZ23.5) have incomplete (ZmJAZ23.6 and ZmJAZ23.7) Jas domains (S1 Table). In summary, this study identified maize JAZ proteins (ZmJAZ4.1, 10.1, 14.1, 23.5, 23.6, 23.7, 27.1, and 33.1) that have Jas domain perturbations likely rendering them resistant to degradation [24] and would have considerable implications for JA desensitization and in physiological processes.

Differential gene expression of large gene families allows plants to finely control their responses with spatial-temporal specificity. In this study, we found that the maize TIFY family genes are expressed in a tissue- and organ-specific manner under basal conditions. Eight JAZ genes (ZmJAZ2, 3, 8, 11, 12, 13, 26, and 27) were found highly expressed across almost 79 different tissue types while nine others (ZmJAZ7, 9, 10, 16, 24, 32, 35, 37, and 38) only accumulated transcripts to low levels (Fig 6). Other ZmJAZ showed greater tissue specificity: in leaves, 14 JAZ genes (ZmJAZ2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18, 20, 21, and 23) were highly expressed (Fig 6), suggesting that JAZ proteins regulate leaf development and defense. Arabidopsis possesses 13 JAZ genes [28], 10 of which are essential for vegetative growth and reproductive [29].

Insect herbivory or mechanical damage rapidly induce expression of JAZ genes in Arabidopsis, and functional analysis with aos and coi1 mutant lines showed that both JA biosynthesis and perception are required in this process [12,30]. In this study, we found that 14 ZmJAZ genes (ZmJAZ3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 18, 20, 23, 25, 31, and 33) are induced by either mechanical wound, exogenous JA application, or both treatments (Fig 7). These results provide pharmacological evidence that JAZ genes from diverse plant species respond by similar cues resulting in similar defensive functions in both monocots and dicots.

Promoter analysis provides insights into the regulation of genes to elucidate their physiological functions. Here, we examined the ZmJAZ promoters for six cis-regulatory elements involved in defense and hormone responses. ABA facilitates stomatal closure in response to abiotic stress such as during drought conditions [54], while auxin signaling regulates tolerance to diverse stresses [55]. SA, JA, and ET are best understood for their roles in plant defense to diverse biotic and abiotic stresses. Here, they activate transcriptional reprogramming to engage defense against various pathogens, pests, and abiotic stresses, such as wounding and salt [56]. JA and ET usually synergistically regulated plant development and tolerance to necrotrophic fungi [57]. GA is a major growth hormone and stress-induced growth reduction is associated with decreases in GA levels [58]. Our result revealed that ZmJAZ gene promoters contain several cis-regulatory elements related to plant hormone and stresses regulation. This is in agreement with a recent study that identified cis-elements associated with ABA, Auxin, MeJA, GA, and stress tolerances in promoters of wheat JAZ genes [43] and consistent with an increasing number of studies that have functionally characterize specific JAZ proteins in plant hormone regulation of defense responses against abiotic and biotic stresses in rice, tomato, maize, and poplar [32,33,42,59]. Thus, it is reasonable to expect that the maize JAZ proteins will emerge as potent mediates in crosstalk hormone signaling crosstalk during plant growth, development, or defense processes.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

An updated census of the maize TIFY family

An updated census of the maize TIFY family