Author Contributions S.E.Y. and N.S.M. conceived and designed the study. S.E.Y. built the quantum cascade laser-coupled IR s-SNOM detection interferometer, prepared samples, performed AFM, IR s-SNOM measurements, imaged immunogold labelled nanowires with AFM along with imaging and analysis of reduction in nanowire diameter. J.P.O. grew biofilms in microbial fuel cell and analysed protein content with R.J. K.R. built the OmcZ model and performed simulations, with help from P.J.D., under the guidance of V.S.B. J.P.O. and W.H. purified nanowire from bacteria, performed CD experiments, and conducted analysis. J.P.O. performed FTIR and fluorescence emission spectroscopy and analysed data with S.E.Y. W.H. and S.E.Y. performed principal component analysis on the IR s-SNOM data. V.S. and Y.G. imaged immunogold labelled nanowires with TEM. Y.G. also carried out CP-AFM measurements and analysed data with P.J.D. Y.G. and S.E.Y performed and analysed nanowire stiffness measurements. S.M.Y. carried out mass spectroscopy as well as Raman spectroscopy and analysed Raman data with S.E.Y. Electrode fabrication using electron beam lithography was carried out by D. V. and Y. G. S. E. Y. and T. V. performed XRD measurements and analysed data with Y.G. A.A. and S.C. performed initial molecular dynamics simulations under the guidance of V.S.B. A.A. constructed the models, coded the analysis scripts, and performed the analysis of molecular dynamics data. N.S.M. supervised the project. S.E.Y. and N.S.M. cowrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

- Altmetric

- Electric field stimulates production of OmcZ nanowires

- IR nanospectroscopy confirms identity of OmcZ nanowires

- OmcZ nanowires are 1,000-fold more conductive than OmcS

- Improving π-stacking of hemes increases conductivity

- Conformation change increases conductivity and stiffness

- Discussion

- Online Methods

- Extended Data

- Supplementary Material

Multifunctional living materials are attractive due to their powerful ability to self-repair and replicate. However, most natural materials lack electronic functionality. Here we show that an electric field, applied to electricity-producing Geobacter sulfurreducens biofilms, stimulates production of previously unknown cytochrome OmcZ nanowires with 1,000-fold higher conductivity (30 S/cm), and 3-fold higher stiffness (1.5 GPa), than the cytochrome OmcS nanowires that are important in natural environments. Using chemical imaging-based multimodal nanospectroscopy, we correlate protein structure with function, and observe pH-induced conformational switching to β-sheets in individual nanowires, which increases their stiffness and conductivity by 100-fold due to enhanced π-stacking of heme groups; this was further confirmed by computational modelling and bulk spectroscopic studies. These nanowires can transduce mechanical and chemical stimuli into electrical signals to perform sensing, synthesis and energy production. These findings of biologically-produced, highly-conductive protein nanowires may help to guide the development of seamless, bidirectional interfaces between biological and electronic systems.

All commercial bioelectronic devices so far rely on the same silicon-based electronics that sustain global information technology and infrastructure1. Despite decades of effort, however, most synthetic and molecular electronic materials remain bio-incompatible and non-biodegradable, and they usually show poor performance due to structural disorder1. Capital costs of equipment for their top-down manufacturing are also rising to $14B per semiconductor fabrication plant2. In contrast, biological systems can construct nanomaterials at low-cost and high yield from the bottom-up2. Non-redox proteins are shown to be conductive in single-molecule measurements, with small electron decay with distance, provided charge is injected into the protein interior via good contact3. However, the conduction mechanism is unknown.

The common soil bacteria Geobacter sulfurreducens naturally produces conductive protein filaments called “microbial nanowires” to export electrons to extracellular electron acceptors, allowing bacteria to respire in harsh environments that lack soluble, membrane-permeable, electron acceptors such as oxygen4. These nanowires have been thought to be type 4 pili, composed of PilA protein5. However, structural analysis found nanowires made up of cytochrome OmcS, with seamless stacking of hemes providing continuous path for electrons (Extended Data Fig. 1a)4. OmcS is essential for bacterial electron transfer to Fe (III) oxide, one of the most abundant minerals in natural soil and sediment environments6. In addition to this short-range (~1–2 µm) electron transfer to minerals via OmcS, G. sulfurreducens generates high current density by forming 100 µm-thick conductive biofilms on electrodes under the influence of electric field in microbial fuel cells, even in the absence of OmcS7.

Previous studies found that another cytochrome OmcZ is not involved in electron transfer to Fe(III) oxide[8], but it is essential for these biofilms generating high current density in bioelectrochemical systems microbial fuel cells[9]. However,immunogold labeling did not show OmcZ throughout these biofilms, but rather accumulation of OmcZ near the electrode surface[10]. As cytochromes were considered monomeric[4], previous studies[91011] presumed that cells may use isolated OmcZ monomers for short-range electron transfer at the biofilm–electrode interface. Therefore, the mechanism for long-range (~100 µm) electron transport in current-producing biofilms has remained unknown.

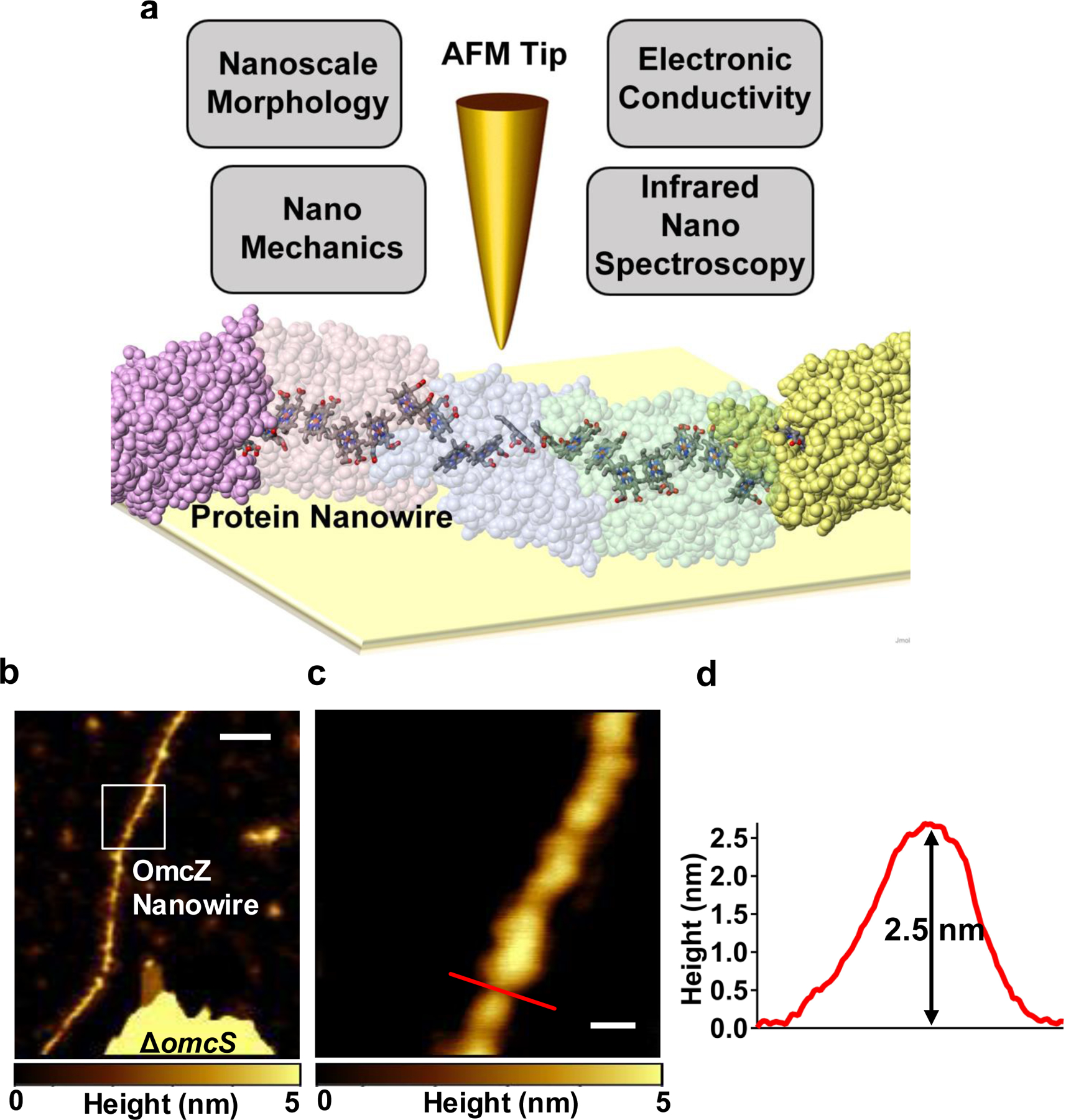

To determine the composition, structure, electrical and mechanical properties of individual nanowires in biofilms, we combined four complementary nanoscopic tools in a multimodal imaging platform (Extended Data Fig. 1a): (1) high-resolution atomic force microscopy (AFM) to identify the protein composition and morphology; (2) infrared (IR) nanospectroscopy using scattering-type scanning near-field optical microscopy (s-SNOM)12 to identify biomolecules through their characteristic IR vibrational signatures; (3) conducting-probe AFM (CP-AFM) to measure electron transport along the nanowire length; and (4) nanomechanical AFM to determine nanowire stiffness. To further investigate the structural features in nanowires that enhance conductivity, we complemented these nanoscale studies with protein modelling and molecular dynamics simulations, cryo-electron microscopy (Cryo-EM), as well as bulk measurements using X-ray diffraction, FTIR, circular dichroism, Raman and fluorescence spectroscopy.

Using a suite of above complementary imaging and spectroscopy methods, here we demonstrate that growing G. sulfurreducens biofilms in an electric field stimulates production of previously unknown OmcZ nanowires that exhibit 1,000-fold higher conductivity than OmcS nanowires. We also find that a low pH-induced formation of beta sheets in OmcS and OmcZ nanowires improves the stacking of hemes and enhances nanowire conductivity and stiffness.

Electric field stimulates production of OmcZ nanowires

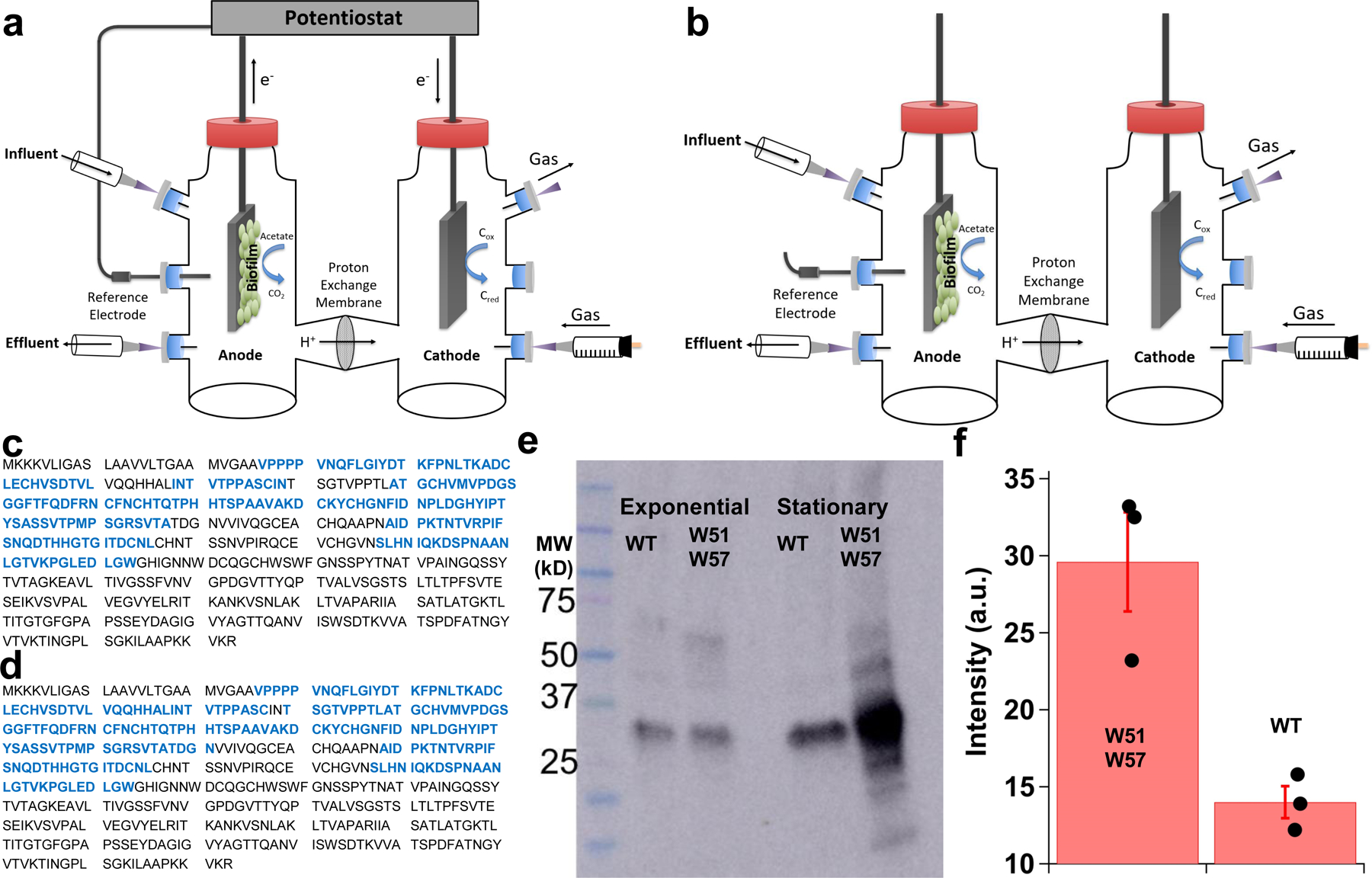

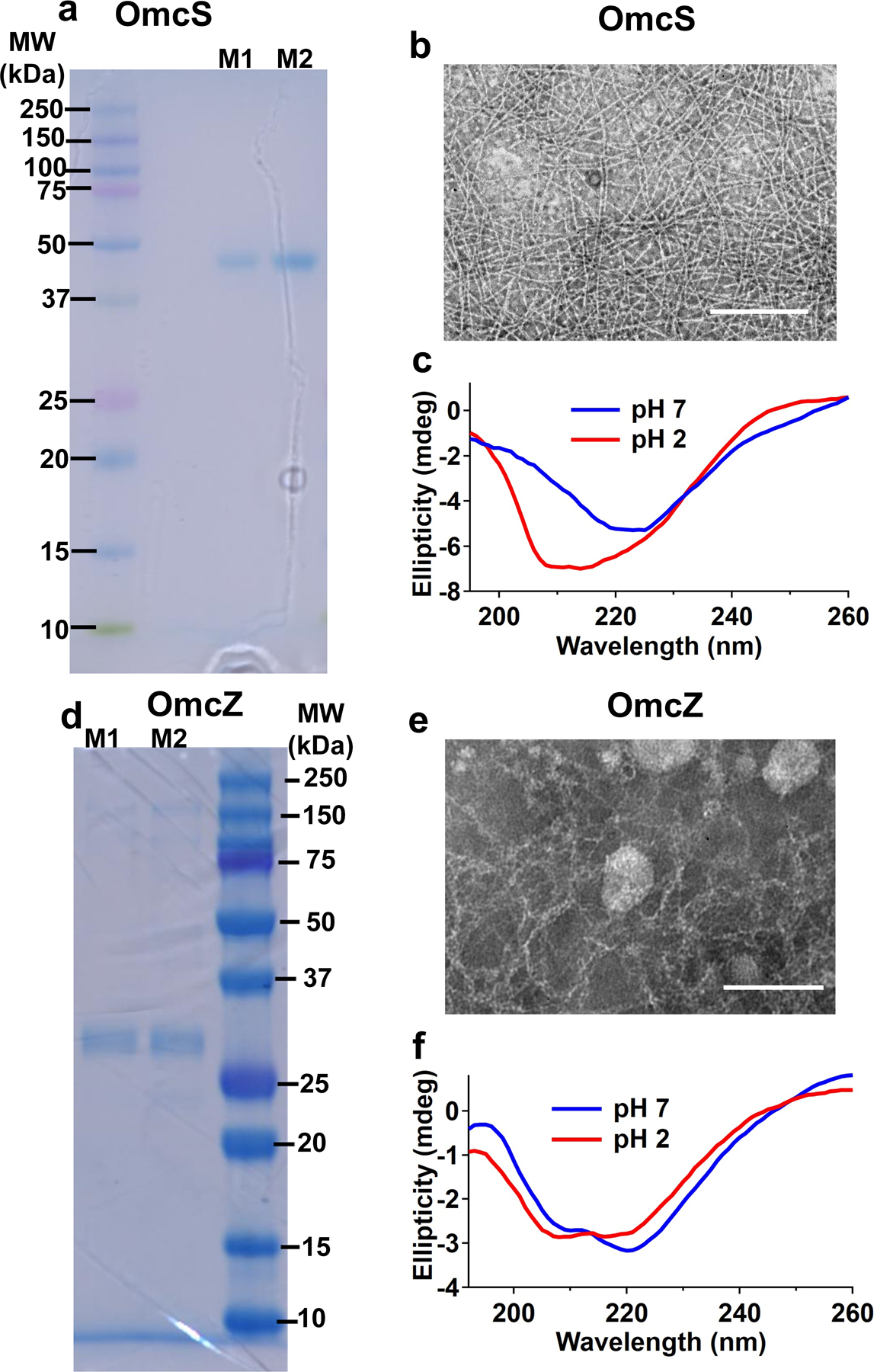

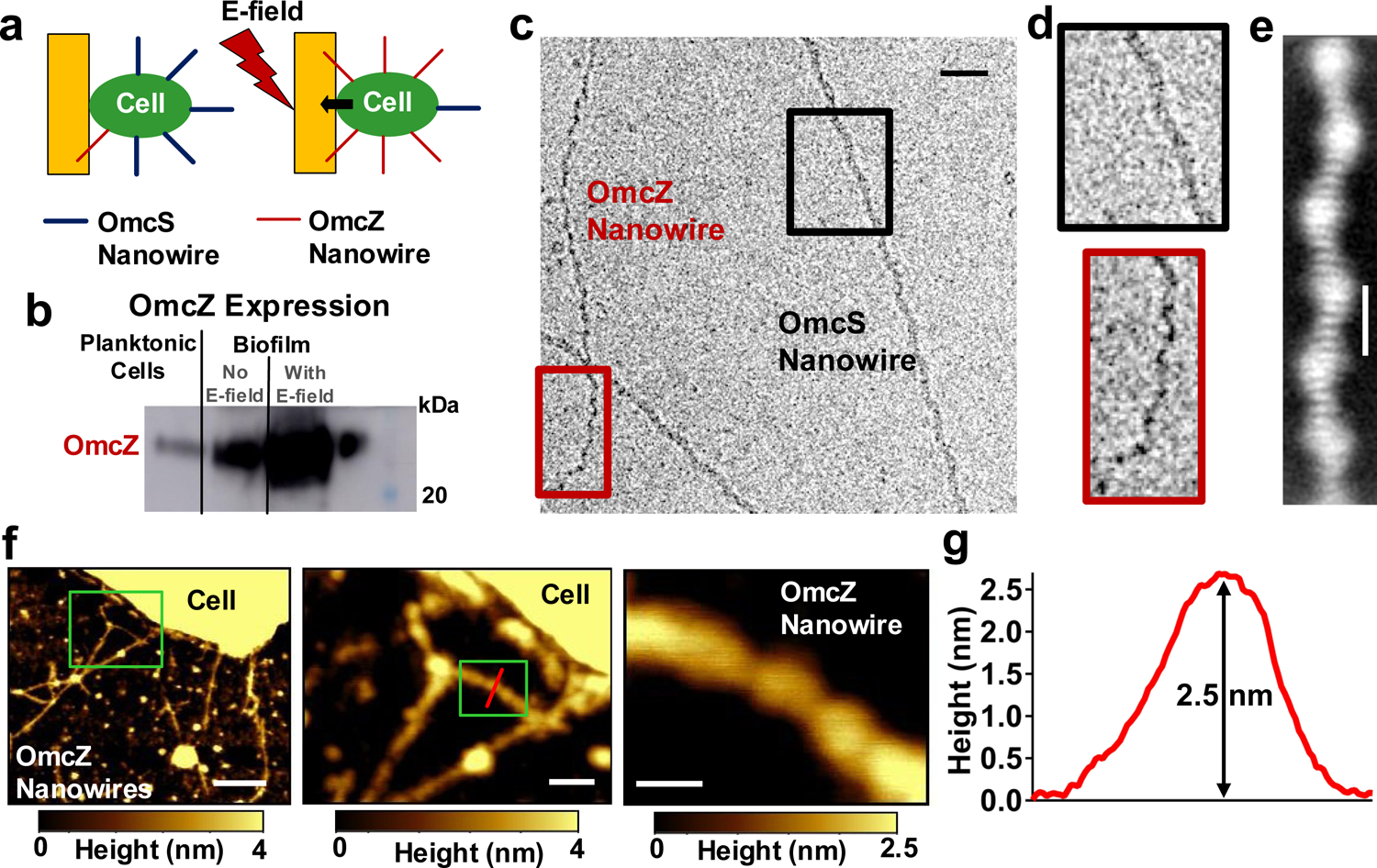

To assess the effect of the electric field on the formation of OmcZ nanowires, we grew wild-type (WT) G. sulfurreducens on graphite anodes serving as an electron acceptor in a microbial fuel cell13, with a continuous supply of fumarate as an alternate, soluble electron acceptor (Fig. 1a, Extended Data Fig. 2a–b). In one case, an electric field was supplied by connecting the anode to the cathode whereas in a control case, the anode was disconnected from the cathode to grow the biofilm at the open circuit potential in the absence of an external electric field. In comparison to planktonic cells, or biofilms grown in the absence of an electric field, biofilms grown in the presence of the electric field showed higher abundance of OmcZ in filament preparations as revealed by both peptide mass spectrometry, and immunoblotting (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 2c–f, Supplementary Fig. 1). Furthermore, cryo-EM showed the presence of ~2.5-nm diameter filaments in these samples in addition to 3.5-nm diameter OmcS nanowires (Fig. 1c–d). Analysis of images of these thinner filaments showed substantially different helical parameters (an axial rise of 57 Å and a rotation of 160°) compared to OmcS nanowires (an axial rise of 46.7 Å and a rotation of −83.1°)4. By analysing these helical parameters, we determined a molecular weight of ~30 kDa for the protomer in these filaments (see methods). This molecular weight is consistent with extracellular OmcZ, whereas intracellular OmcZ is 50 kDa8. All these results show that the electric-field applied to biofilms induces overexpression of OmcZ and suggest that the ~2.5-nm diameter filaments observed in cryo-EM images could be made up of OmcZ.

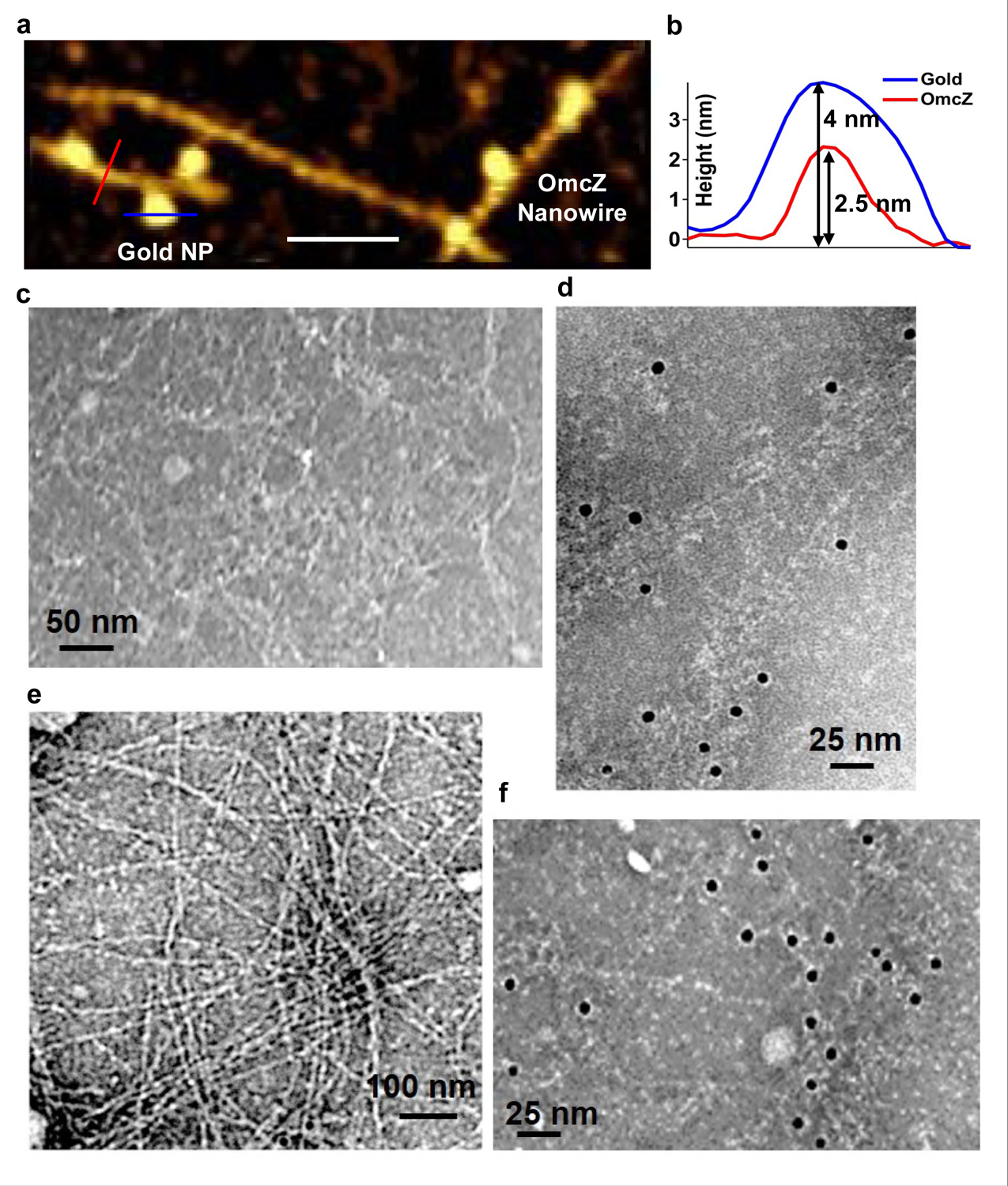

AFM images of WT cells grown under an electric field (Fig. 1f–g), and a ΔomcS strain (Extended Data Fig. 1b–c, grown under conditions that overexpress OmcZ8 ) showed filaments of ~2.5 nm in diameter on their surface with height and morphology (Fig. 1g, Extended Data Fig. 1d) similar to those of cryo-EM images (Fig. 1c–e). We further analysed these 2.5 nm-diameter filaments from multiple strains by performing immunogold labelling with anti-OmcZ antibodies, using both AFM (Extended Data Fig. 3a–b) and negative-stain TEM (Extended Data Fig. 3c–f). Only these 2.5 nm-diameter filaments showed the labelling whereas no labelling was found for filaments of a ΔomcZ strain or in the absence of anti-OmcZ antibody (Extended Data Fig. 3c,e). These studies confirmed that the labelling was specific to 2.5 nm-diameter filaments and revealed that these filaments were made of OmcZ. This substantial difference in thickness between nanowires of OmcZ (~2.5 nm) and OmcS (~3.5 nm)4 (Extended Data Fig. 4) was used to confirm that nanowires used for infrared nanospectroscopy, CP-AFM, and nanomechanical studies are the same nanowires characterized by cryo-EM and immunogold labelling.

We also analyzed the 2.5-nm-diameter filaments of a ‘W51W57’ mutant bacterial strain where phenylalanine and tyrosine at location 51 and 57, respectively, in the PilA protein were replaced with tryptophan (W) residues [14]. These filaments also showed labeling with anti-OmcZ antibodies (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b,f). Immunoblotting and mass-spectrometry analysis of filament preparations revealed that the W51W57 strain produced more OmcZ than WT (Extended Data Fig. 2c–f). Our finding that the strain W51W57 produces more OmcZ is also consistent with previous studies[1516] that pilA deletion affects the extracellular expression of both OmcS and OmcZ.

IR nanospectroscopy confirms identity of OmcZ nanowires

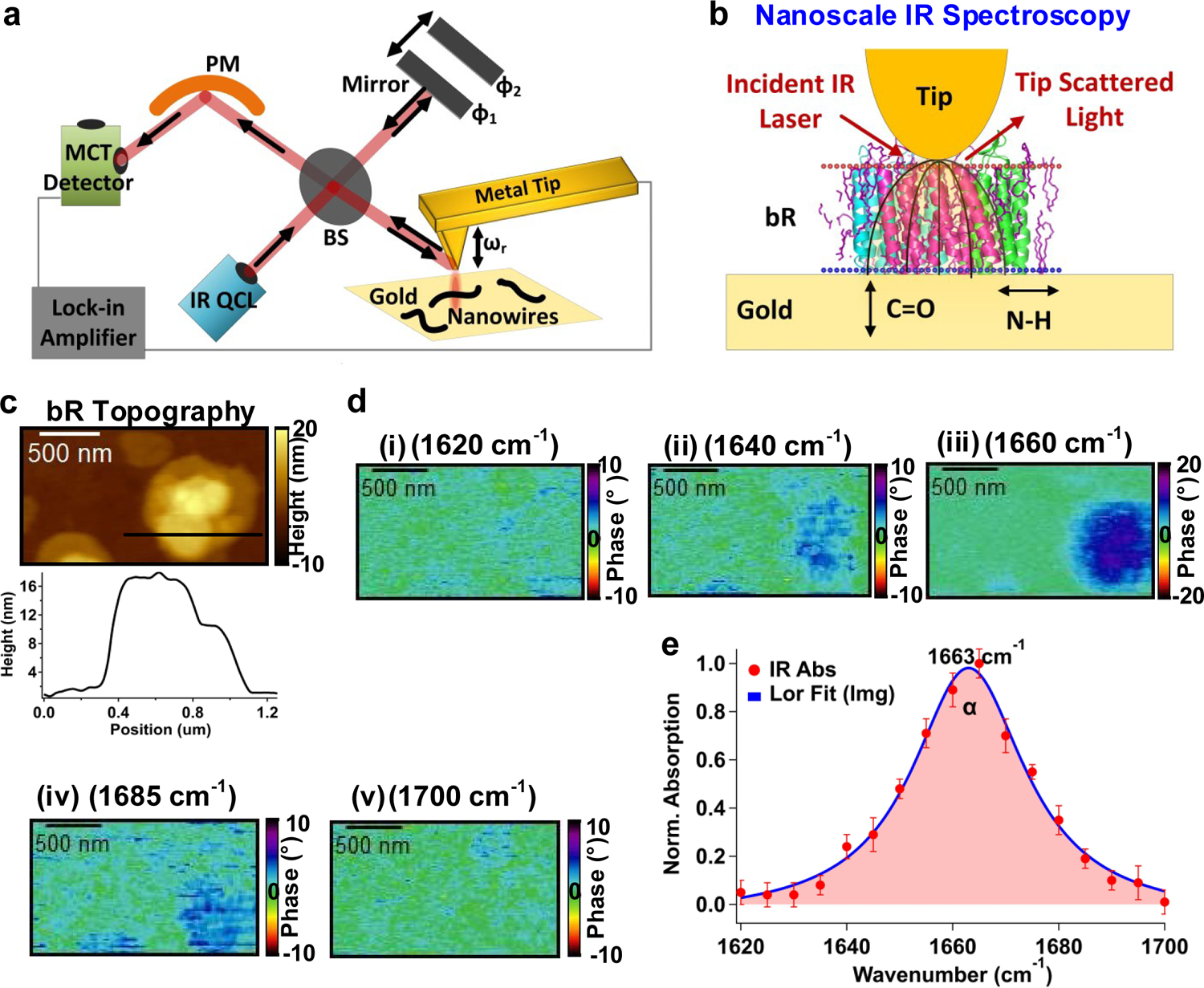

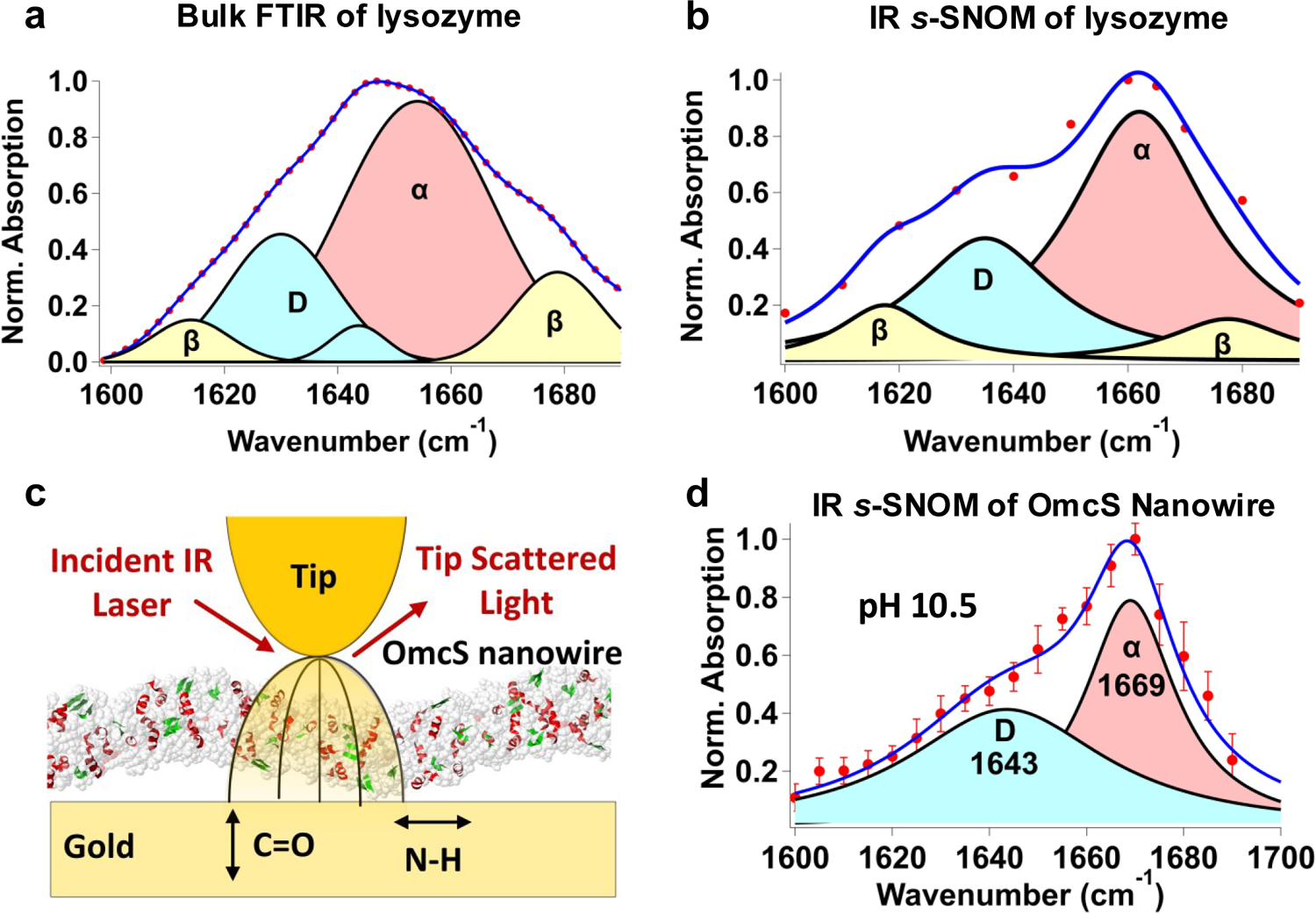

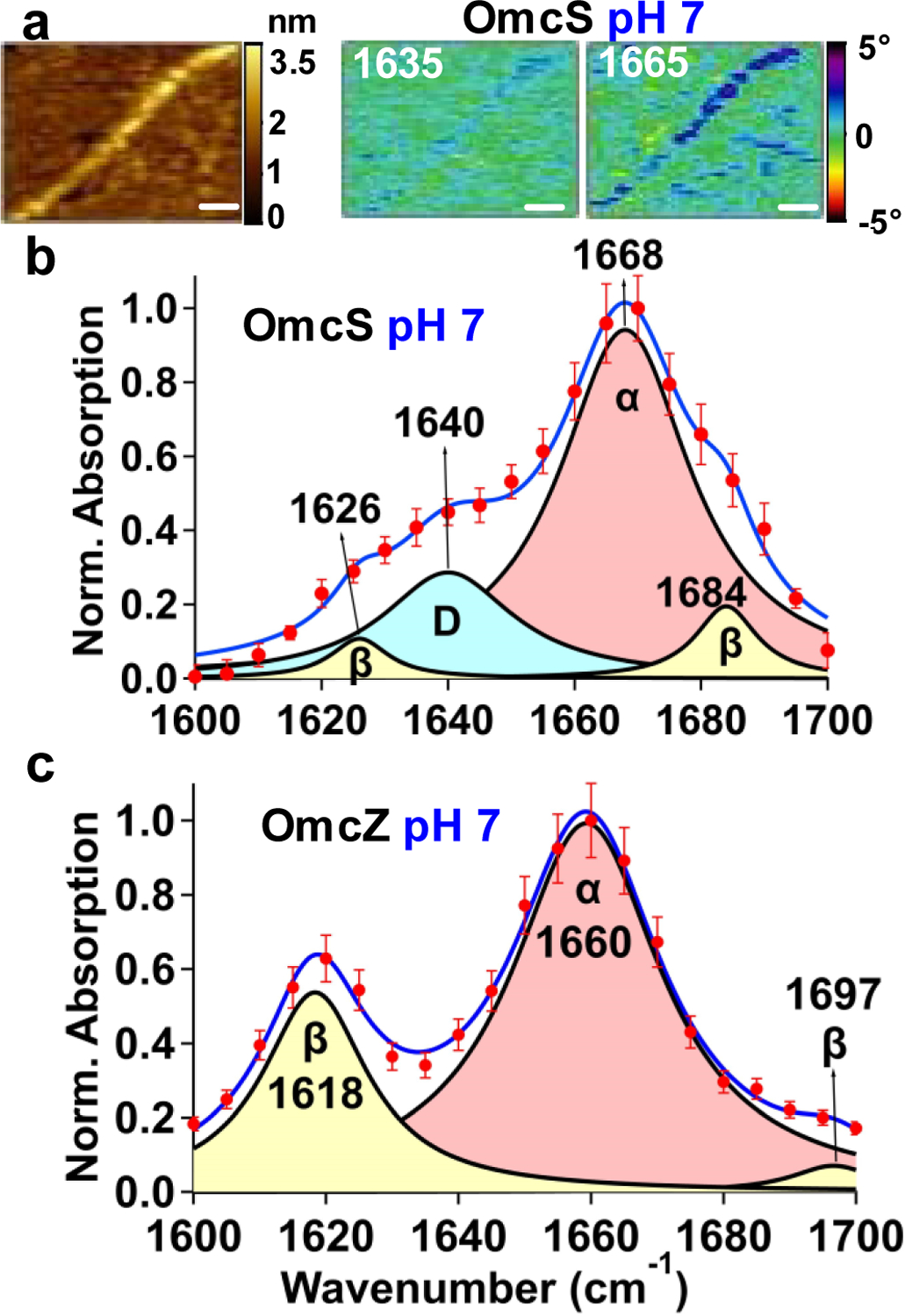

To further determine the composition of individual nanowires, we visualized their protein secondary structure by imaging the characteristic variations in the line shape of the IR-active amide I vibrational mode (primarily C=O stretch, 1,600–1,700 cm−1)[17] (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). IR s-SNOM provides quantitative information on the secondary structure for comparisons of different proteins under various environments, although the measured amount of each secondary structure can differ from the amounts of secondary structure in the cryo-EM structure due to SNOM sensitivity toward C=O versus N–H stretch[12] (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Previously, we used IR s-SNOM-based nanoscopic chemical imaging to directly visualize water molecules as they bind to individual minerals[18]. Here, to evaluate the reliability and accuracy of our imaging platform for protein structure determination, we first performed IR s-SNOM imaging and spectroscopy of two proteins with well-known structures: bacteriorhodopsin[1219] and lysozyme[17] as well as on individual OmcS nanowires at pH 10.5 (conditions used to solve their atomic structure[4], Extended Data Figs. 5 and 6). As expected[1219], the bacteriorhodopsin exhibited purely α-helical spectra, indicated by a single peak at 1,663 cm−1 (Extended Data Fig. 5e)[17] while lysozyme showed not only the α-helical peak but also two additional peaks at 1,618 and 1,678 cm−1 indicative of β-sheets[17] (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b)[17]. Notably, for lysozyme, the relative numbers of α-helices versus β-sheets measured by IR s-SNOM were comparable to those obtained by bulk FTIR, in good agreement with the literature[20] (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b and Supplementary Table 1a). At pH 10.5, the pH used to solve the cryo-EM structure of OmcS[4], the IR s-SNOM images and spectra of OmcS nanowires showed an α-helical component with the remainder being loop region showing coils and turns (Extended Data Fig. 6c,d). These results were in agreement with the cryo-EM structure of OmcS (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID 6EF8)[4] that showed largely turns and coils with only 12% helices and 6% β strands[4] (Extended Data Fig. 6c). Together, these studies validate our nanoscale imaging approach for visualization and quantification of protein secondary structure.

At pH 7, by IR s-SNOM, OmcS nanowires exhibited an α-helical component and coil/turns (Fig. 2a–b, Supplementary Table 1b), in agreement with previous studies of the secondary-structure of purified OmcS monomers21. In contrast, OmcZ nanowires showed a substantial amount of β-sheets and little coil/turns (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Table 1b), consistent with previous secondary-structure studies of purified OmcZ monomers8. Taken together, IR s-SNOM studies, combined with cryo-EM, mass spectrometry, immunoblotting and immunogold labelling show that the electric-fields applied to biofilms stimulate the production of OmcZ nanowires. As the electric-field is strongest near the electrode interface and decreases away from the electrode, OmcZ expression is expected to be maximum at the biofilm-electrode interface. This could explain prior experiments which found that cells show maximum accumulation of OmcZ10 and highest metabolic activity22 near the biofilm-electrode interface.

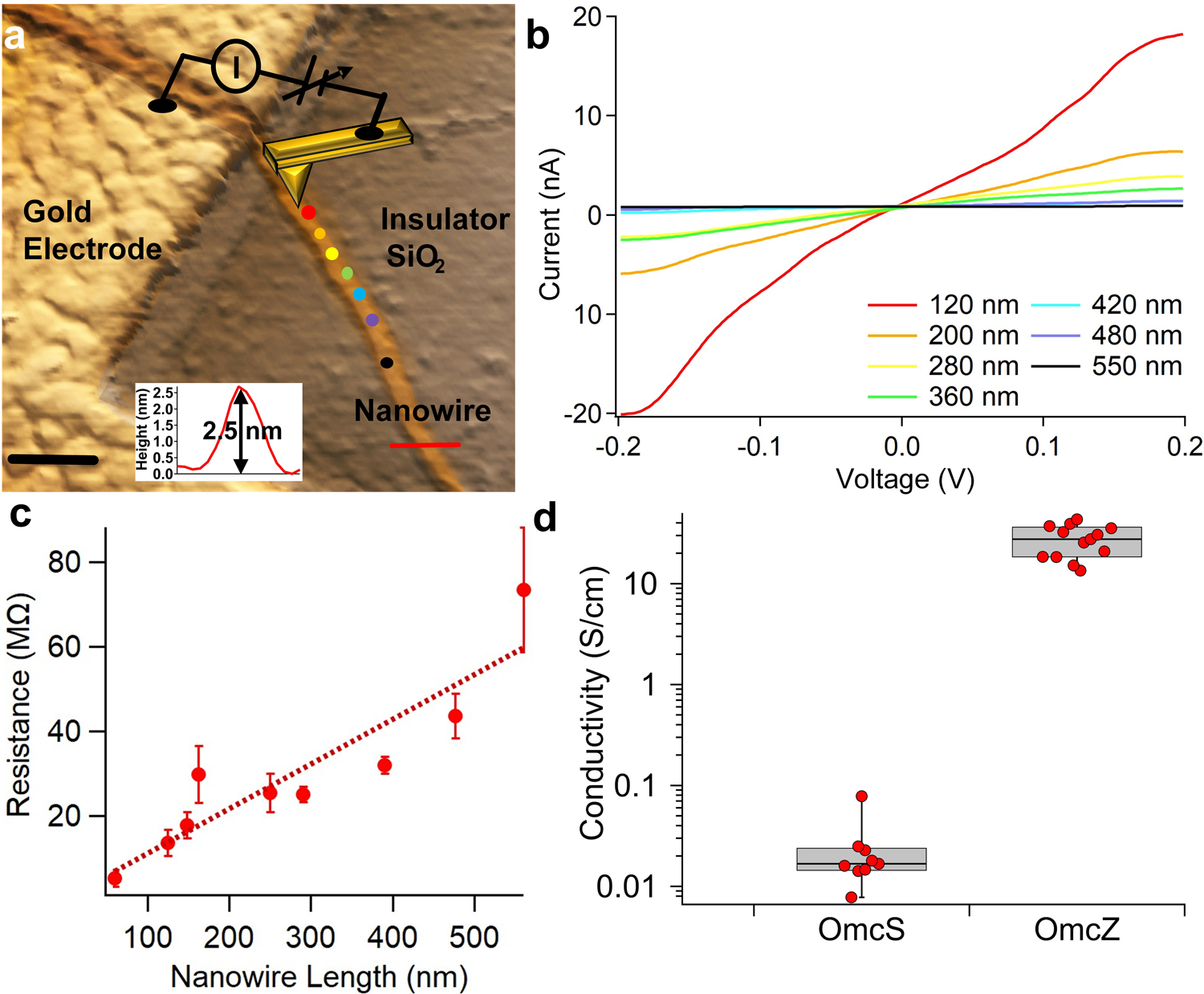

OmcZ nanowires are 1,000-fold more conductive than OmcS

To determine the electronic conductivity along the individual OmcZ nanowires, we placed nanowires across a gold/silicon dioxide (SiO2) interface with the AFM tip being held in contact with an isolated nanowire at various distances away from the gold electrode (Fig. 3a). The current along the nanowire was measured as a function of the DC bias applied between the tip and the gold electrode as a function of nanowire length to determine the contact-free, intrinsic electrical resistance and hence conductance (Fig. 3b). Control measurements by touching the tip directly to gold or insulating SiO2 surface yielded expected results, demonstrating the validity of our approach (Supplementary Fig. 2). The resistance of OmcZ nanowires increased linearly with nanowire length, indicative of a wire-like behavior23 (Fig. 3c). Remarkably, the OmcZ nanowires showed 1,000-fold higher conductivity than OmcS at pH 7 (Fig. 3d), which could explain the ability of cells to transport electrons over 100 µm in biofilms7.

Improving π-stacking of hemes increases conductivity

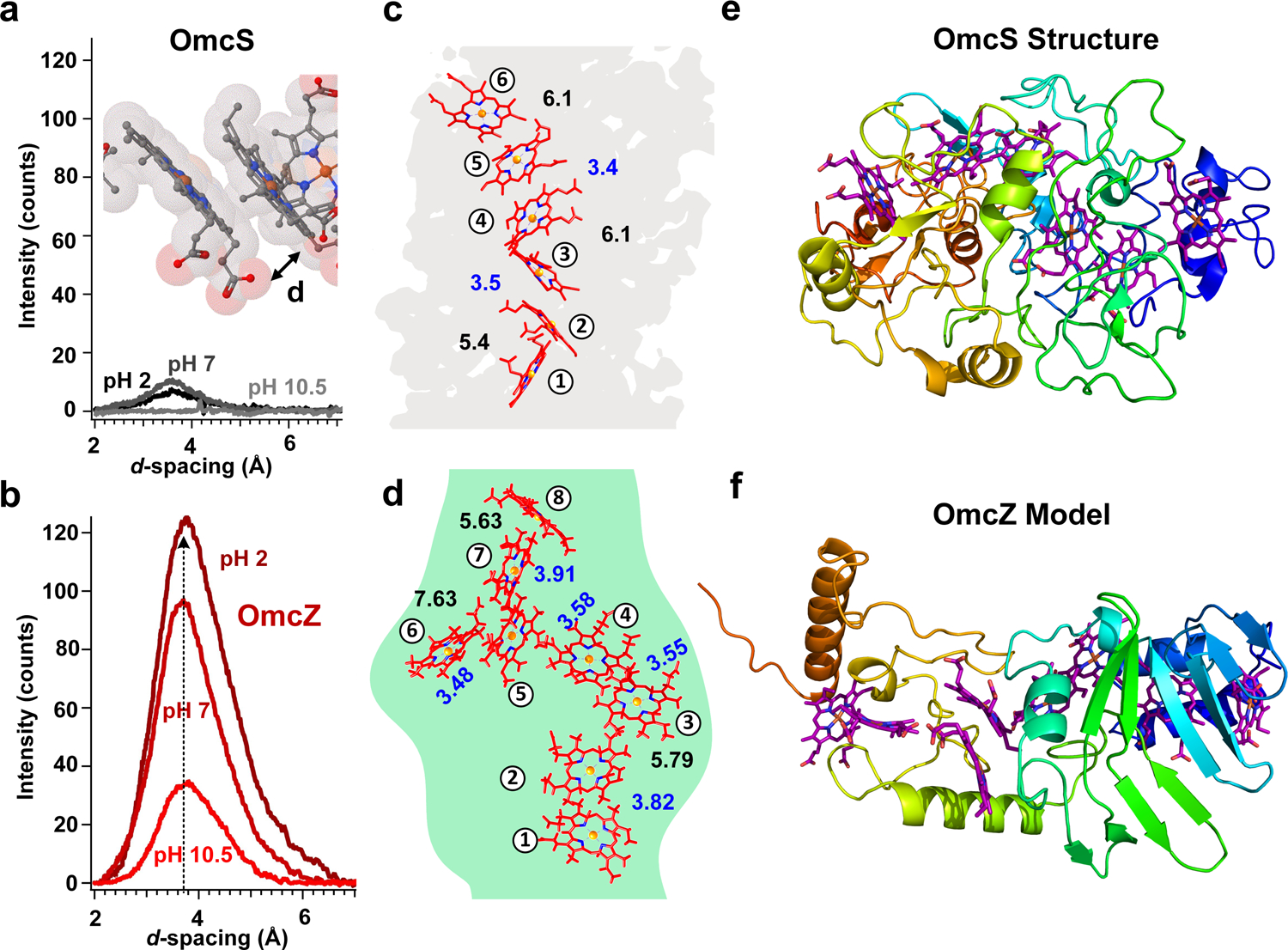

Grazing-incidence micro-X-ray diffraction (GIµXRD) patterns of OmcZ nanowires showed a more intense peak than OmcS nanowires with d-spacing of 3.6 Å, (Fig. 4a,b). This d-spacing likely corresponds to the face-to-face π-stacking distance between parallel-stacked hemes, as suggested by the structure of OmcS nanowires (Fig. 4a, inset)4. Improved π-stacking increases the effective conjugation length, yielding a longer mean free path for electrons that enhances conductivity24. Therefore, our structural analysis suggested that the enhanced conductivity of OmcZ nanowires results from increased crystallinity and reduced disorder within the nanowires (Fig. 4b).

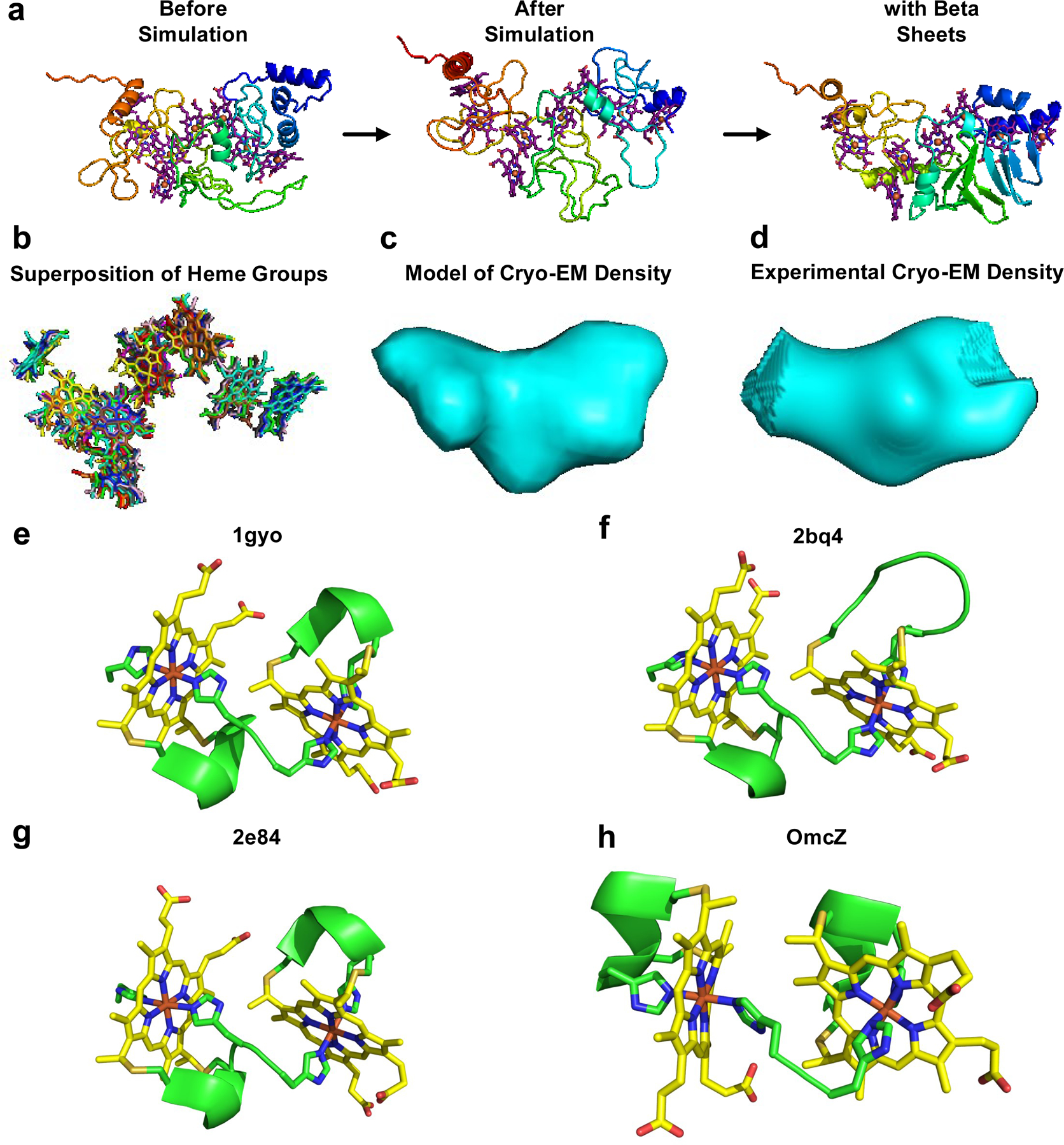

We built a computational model of OmcZ structure to understand the molecular mechanism underlying the increased stacking of hemes in OmcZ as compared to OmcS (Fig. 4). Based on the finding that many heme proteins show similar stacking arrangement of hemes25(Extended Data Fig. 7b), we used this arrangement of 8-hemes as a template for OmcZ model, which agreed well with the cryo-EM density map for OmcZ nanowire (Fig. 4d). These 8-heme protein structures25 revealed a dense packing and a substantially different arrangement of hemes when compared to OmcS nanowires (Fig. 4c). This dense packing of hemes is consistent with 8 hemes packed in the 30 kDa OmcZ protomer vs. 6 hemes packed in the 45 kDa OmcS protomer (Fig. 4c). Comparison of edge-to-edge heme-heme distances showed that OmcS has only two heme pairs within π-stacking distance (3.5–4 Å)26 whereas the 8-heme protein structures showed 5 heme pairs within π-stacking distance (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 2, shown in blue). These 8-heme protein structures are thus consistent with the X-ray microdiffraction data and further indicate that the increased conductivity of OmcZ nanowires is due to a more compact molecular structure with a higher density of heme groups when compared to OmcS nanowires (Fig. 4c,d). The polymerization of OmcZ could further reduce the distance between hemes for closer stacking of hemes in OmcZ nanowires than that found in the OmcS nanowires. In contrast to OmcS nanowire structure, the OmcZ model showed beta-sheet-rich structure (Fig. 4e–f, Extended Data Fig. 7), in agreement with IR s-SNOM studies (Fig. 2). To further evaluate the validity of OmcZ model, we compared the heme ligation by two consecutive histidines in OmcZ to three different structures of cytochrome c3 (PDB IDs: 1gyo, 2bq4 and 2e84) (Extended Data Fig. 7e–h). The amino acid sequence of c3 contains CXXCHH motif with one proximal and one distal histidine in the heme pairs while OmcZ contains two distal histidines. All four structures showed consecutive histidines causing tight heme T-junction with similar heme-heme distances.

Conformation change increases conductivity and stiffness

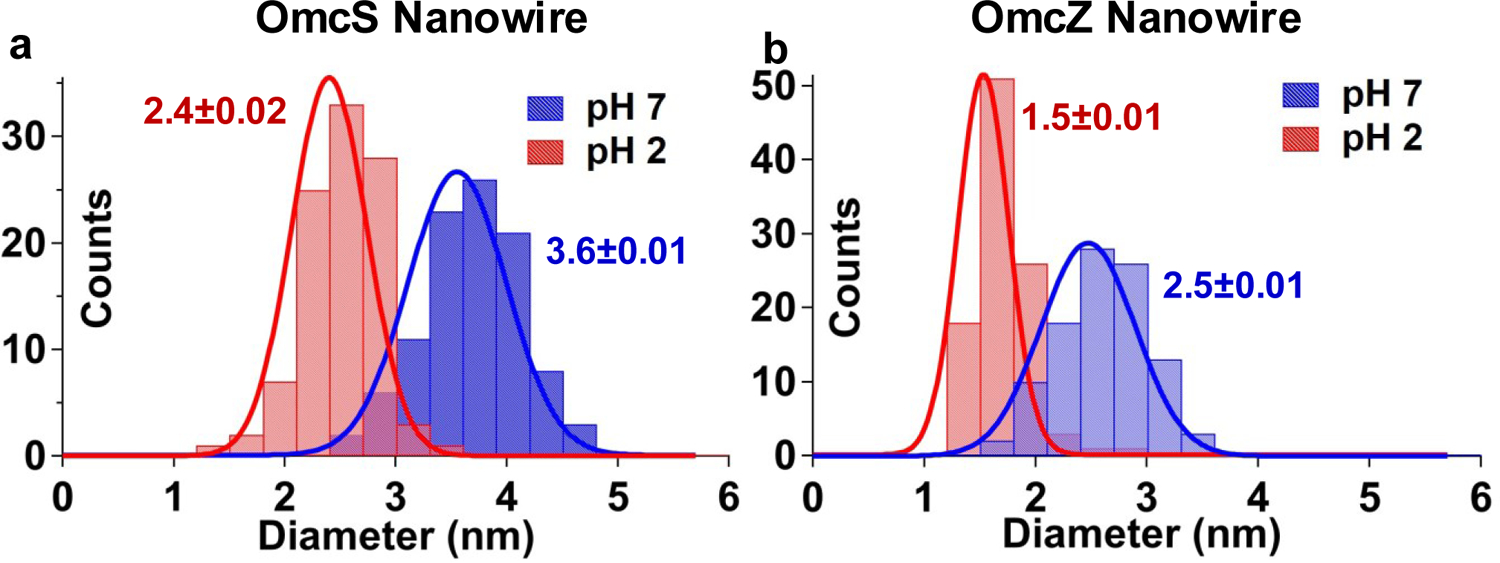

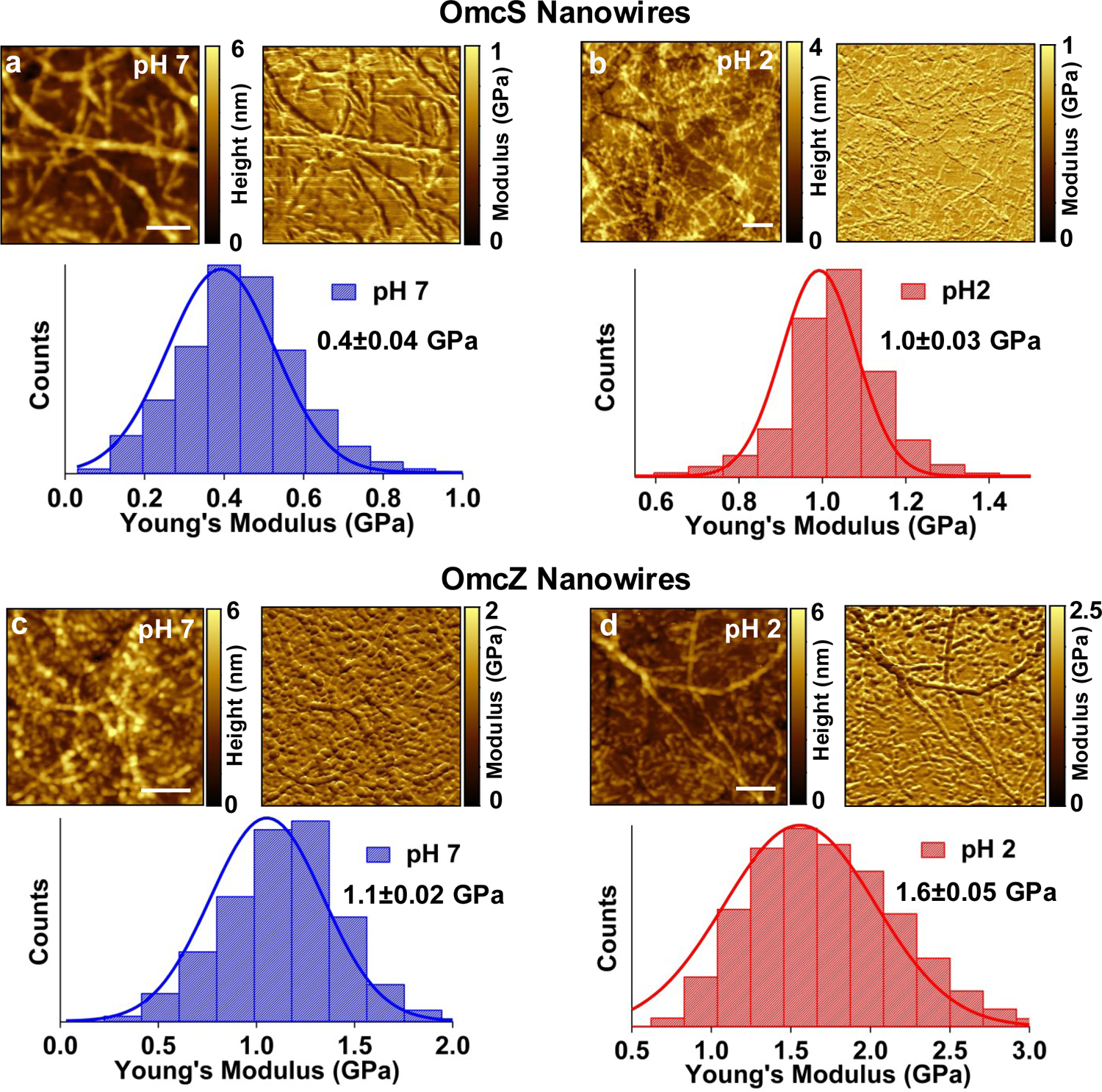

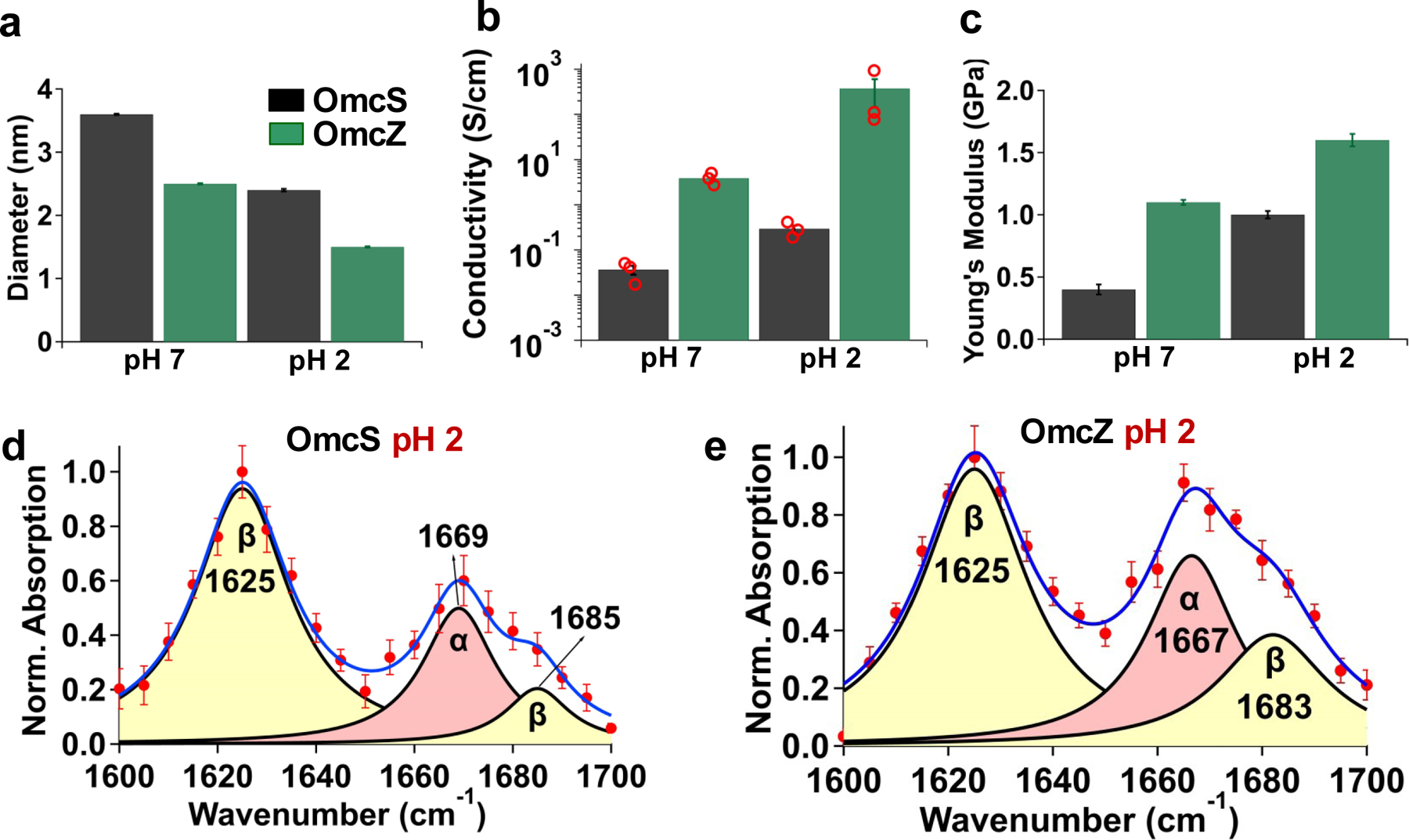

We had previously found that the conductivity of G. sulfurreducens nanowires increases at lower pH7,14,27,28, but the underlying mechanism remains unknown28. Here, we find evidence of pH-induced structural changes that correlate with the increased conductivity. AFM imaging revealed that the nanowire diameter decreased from 3.6 nm to 2.4 nm for OmcS and from 2.5 to 1.5 nm for OmcZ (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 4). This reduction in nanowire diameter upon lowering the pH helps to explain the increased π-stacking of hemes (Fig. 4a–b). Thus, OmcS and OmcZ nanowires undergo very large conformational changes (due to decrease in diameter by 12 Å and 10 Å, respectively) that significantly enhance the conductivity (by 10- and 100-fold respectively, Fig. 5b) and the stiffness (by 2.5- and 1.5-fold respectively, Fig. 5c, Extended Data Fig. 8). The conformations affecting conductivity of synthetic molecules were previously found to remain local and < 2 Å, thus yielding at most a 10-fold change in conductivity29–31. In contrast, OmcZ nanowires show a 10 Å conformation change and 100-fold increase in conductivity. We anticipate that such very large-scale conformational changes, responsible for stereoelectronic effects, could find applications such as switches in memory and logic devices29–31.

To further delineate the mechanism underlying the pH-induced conformational changes, we located nanowires via AFM and compared their corresponding IR s-SNOM images at pH 7 (Fig. 2) and pH 2 (Fig. 5d,e). IR s-SNOM of the OmcS nanowires at pH 7 showed prominent absorption at 1665 cm−1, corresponding to α-helices (Fig. 2b). The analysis of the amide I band showed 70% α-helical, 10% β-sheet, and 20% coil/turn (Supplementary Table 1b). Upon lowering the pH to 2, the absorption at 1625 cm−1, which is assigned to β-sheets17, increased 7-fold (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Table 1b). Further, the peak at 1640 cm−1 corresponding to coil/turn loops disappeared (Fig. 5d) along with a 3-fold decrease in the α-helix peak (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Table 1b). Therefore, much of the α-helical and coil/turn structures in the OmcS nanowires converted to β-sheets at low pH. Consequently, the stiffness of OmcS nanowires increased 2.5- fold to 1 GPa at pH 2, likely due to an increased number of intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the newly formed β-sheets (Fig. 5c–d, Extended Data Fig. 8)32. Furthermore, the conductivity increased 10-fold to 0.3 S/cm at pH 2 (Fig. 5b). Therefore, the increase in β-sheet structure can account for the reduction in diameter of OmcS nanowires at pH 2 and their increased conductivity as well as stiffness (Fig. 5a–c, Extended Data Figures 4, 8).

Upon lowering the pH from 7 to 2, OmcZ nanowires exhibited a net 10,000-fold higher conductivity (400 S/cm) and 4-fold higher stiffness (1.6 GPa) when compared to OmcS nanowires at pH 7 (Fig. 5b–c, Extended Data Fig. 8). IR s-SNOM revealed that at pH 7, OmcZ nanowires displayed a 7-fold increase in β-sheets over OmcS nanowires (Fig. 2b–c, Supplementary Table 1b). At pH 2, the β-sheet content in OmcZ nanowires further increased 3-fold than at pH 7 (Fig. 5e, Supplementary Table 1b). These results suggest that OmcZ nanowires have highly ordered β-sheets that enhance their conductivity and stiffness (Fig. 5b,c) as well as confer a more compact structure than the OmcS nanowires (Figures 4d,f, 5a).

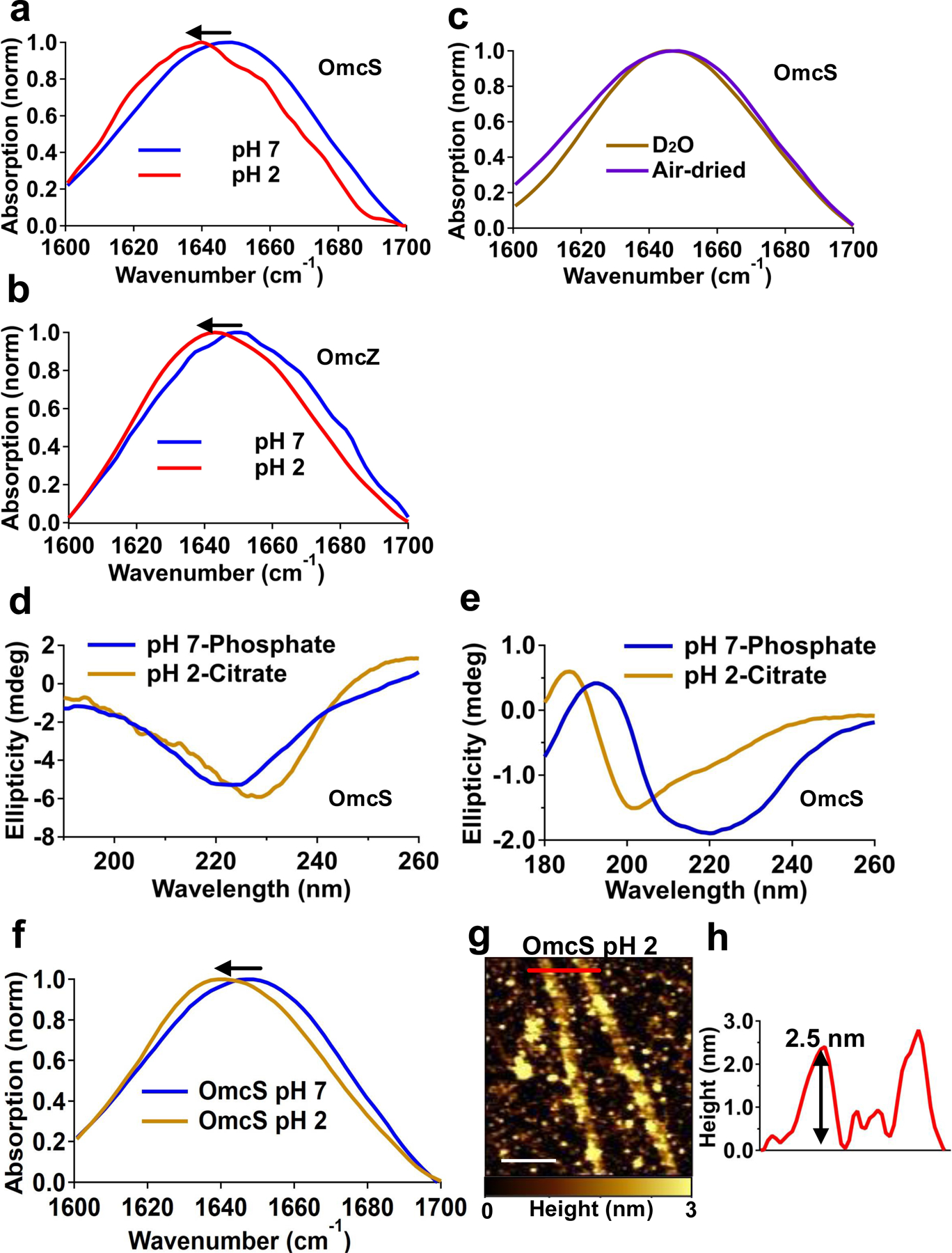

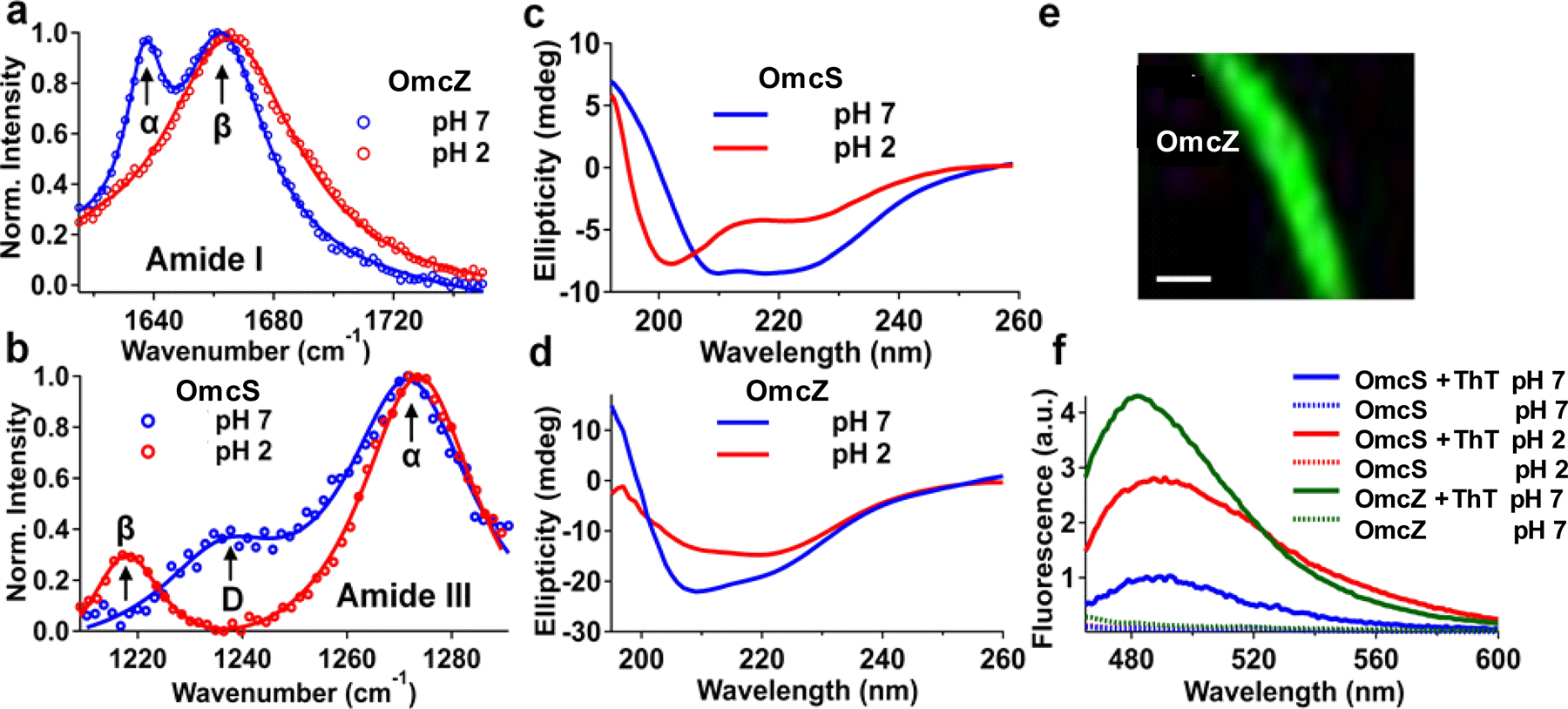

AFM and IR s-SNOM measurements were performed under ambient conditions33 to maintain the native protein conformation. The measured heights of OmcS and OmcZ nanowires using AFM were consistent with those obtained from Cryo-EM (Fig. 1c,d), validating the comparative analysis. To further quantify the conformational changes, we used four additional complementary methods: FTIR, Raman, fluorescence emission spectroscopy and circular dichroism (CD) (Fig. 6, Extended Data Figures 9–10). FTIR revealed formation of β-sheets induced upon lowering the pH for both OmcS and OmcZ nanowires as evidenced by a red shift in the amide-I peak (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c). However, the frequency shift was lower than that probed by IR s-SNOM, due to the diffraction-limited resolution of bulk FTIR12,17.

Raman spectroscopy of nanowires of the W51W57 strain in the amide I mode showed that α-helical regions34 (1637 cm−1) at pH 7 transform into β-sheets34 (1665 cm−1) at pH 2 (Fig. 6a), consistent with IR s -SNOM studies on individual OmcZ nanowires (Fig. 2c). The amide III mode was also sensitive to conformational changes (Fig. 6b). For nanowires of the WT strain, the coil/turn loop region (1240 cm−1) and part of the α-helical region (~1270 cm−1 ) transformed into β-sheets34 (1218 cm−1) at pH 2 (Fig. 6b), consistent with IR s-SNOM studies on individual OmcS nanowires (Fig. 2b, 5d).

In addition, the CD spectra of WT nanowires at pH 7 displayed the characteristic α-helical structure36 with minima near 208 nm and 222 nm (Fig. 6c) in agreement with OmcS nanowire structure4. At pH 2, the intensity at both absorption minima decreased (Fig. 6c), indicating lower α-helical content. Importantly, a new absorption minimum appeared at 204 nm (Fig. 6c), consistent with a higher β-sheet content36. In contrast, nanowires of the W51W57 strain had high content of β-sheets at both pH 7 and 2 (Fig. 6d), in agreement with our IR s-SNOM studies on individual OmcZ nanowires (Figures 2c, 5e). The amounts of α-helix and β-sheet quantified with CD Pro (CDSSTR method)35,36 were consistent with the IR s-SNOM results (Supplementary Table 1c). Purified OmcS and OmcZ nanowires from omcZ and KN400 strains respectively also showed conformational changes similar to nanowires of WT and W51W57 strains (Extended Data Fig. 10, Supplementary Fig. 3), further confirming that the observed conformational changes are due to nanowires.

We also measured the fluorescence emission near 485 nm of thioflavin T, a β-sheet specific dye,37 upon binding with nanowires, and found homogenous and specific binding (Fig. 6e). Fluorescence emission of nanowire-bound thioflavin T increased ~3 fold as the pH was reduced from 7 to 2 (Fig. 6f), consistent with the pH-induced β-sheet formation in OmcS nanowires. Nanowires of the W1W57 strain showed a high β-sheet content, as evidenced by substantial thioflavin T fluorescence at pH 7 (Fig. 6f), in agreement with studies on OmcZ nanowires (Fig. 2c). These four complementary methods further show the pH-induced structural transition to β-sheets in OmcS and OmcZ nanowires as identified by IR s-SNOM.

Discussion

Our studies show that the OmcZ nanowires confer conductivity to electricity-producing biofilms that could explain high biofilm conductivity even in the absence of OmcS nanowires7. Lowering the pH of OmcS and OmcZ nanowires to pH 2 caused permanent structural transition to a more conductive β-sheet form. Denaturation typically destroys protein function. However, we found that at pH 2, the conductivity of OmcZ nanowires increases 100-fold at pH 2 (Fig. 5b) and nanowires maintain similar morphology (Extended Data Fig. 9). Therefore, it is unlikely that the protein is denatured. Furthermore, the structural change was irreversible, confirming permanent transition to beta sheets at pH 2. Recent studies have emphasized the need for understanding the mechanism of environmentally-triggered conformational changes in proteins for the design of protein-based functional materials38. Our finding that coil/turns transform into β-sheets in microbial nanowires provides a mechanism for pH-induced conformational changes that reduce their diameter and enhance stiffness and conductivity. Lowering the pH can induce the formation of β-sheets in synthetic peptides39–41 and the interaction of cytochrome c with SDS causes a transition to β sheets42. A similar effect could explain the pH-induced formation of β-sheets that reduces the diameter of microbial nanowires.

Another mechanism that could account for the pH-induced reduction of nanowire diameter is a dehydration effect that causes proteins and other polymers to adopt a more compact structure at lower pH43–45. In particular, distal histidine coordinating to heme can stabilize the water molecule within the heme pocket by accepting a hydrogen bond44. At low pH, the histidine becomes protonated and swings out of the heme pocket, thus destabilizing the water occupancy and leading to dehydration44. Additional structural studies will help evaluate these possibilities.

Our findings that highly-conductive microbial nanowires contain β-sheets contrast with all prior studies that have assumed that nanowires of both G. sulfurreducens WT and W51W57 strains are made up of PilA with a purely α-helical structure28. Solution NMR studies of the PilA monomer have indicated helical structure even at pH 528. Therefore, combined with immunogold labelling and cryo-EM, our structural and functional studies suggest that highly-conductive microbial nanowires are composed of c-type cytochromes and not PilA.

In summary, we have demonstrated the feasibility of manipulating the production and structure of protein nanowires to control their conductivity and stiffness. Our study established the capabilities of multimodal nanospectroscopic approaches for visualizing and quantifying the large-scale conformational changes in biomolecules. Precise control of electronic and mechanical properties of nanowires can be achieved via targeted environmental changes such as changing the pH which alters heme stacking or applying an electric-field. Previous studies have shown that an electric field can activate a synthetic gene circuit by creating an oxidizing environment46. Additional studies are required to evaluate if a similar mechanism plays a role in these natural systems. Our quantitative method to visualize conformation-induced functional changes is likely applicable to a variety of molecular systems. With OmcZ nanowires displaying a million-fold higher conductivity than synthetic biodegradable materials1, we anticipate these new materials will introduce several new features urgently needed for the next generation of bioelectronics, including low cost, ease of synthesis, lack of toxicity, mechanical flexibility, as well as scalable and facile processing with controlled biological properties1.

Online Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Geoebacter sulfurreducens wild-type (WT) strain PCA (designated DL-1) (ATCC 51573, DSMZ 12127)4, the omcS knock-out mutant strain6 (designated omcS), the omcZ knock-out mutant strain9 (designated omcZ), the omcZ knock-in strain that overexpresses OmcZ47 (designated ZKI), strain W51W5714 and strain Aro548 were obtained from our laboratory culture collection. The cultures were maintained at 30 °C or at 25 °C under strictly anaerobic conditions in growth medium supplemented with acetate (10 mM) as the electron donor and fumarate (40 mM) as the electron acceptor. These strains were grown under electron acceptor-limiting conditions that increases OmcZ expression (Fig. 1b, Extended Data Fig. 2e)13. We found that G. sulfurreducens WT (DL1) strain primarily makes OmcS nanowires whereas strain W51W57 overexpresses OmcZ (Extended Data Fig. 2e) and shows abundance of OmcZ nanowires (Extended Data Fig. 3a,f). Therefore, unless otherwise noted, WT strain was used to focus on studies of OmcS nanowires whereas W51W57 strain was used to focus on studies of OmcZ nanowires. As described previously4, the cells were grown in sterilized and degassed NBAF medium13, and 1L NBAF medium contained the following: 0.04 g/L calcium chloride dihydrate, 0.1 g/L magnesium sulphate heptahydrate, 1.8 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 0.5 g/L sodium carbonate, 0.42 g/L potassium phosphate monobasic, 0.22 g/L potassium phosphate dibasic, 0.2 g/L ammonium chloride, 0.38 g/L potassium chloride, 0.36 g/L sodium chloride, vitamins and minerals as listed in13. Resazurin was omitted and 1 mM cysteine was added as an oxygen scavenger. The cells were grown on electrodes under electron acceptor-limiting conditions to induce the expression of OmcZ nanowires13 (Fig. 1a,f).

G. sulfurreducens nanowire preparation and biochemical characterization.

As described previously4, nanowires were separated from bacteria and extracted via centrifugation14 and maintained in 150 mM ethanolamine buffer at pH 10.5 in a manner similar to structural studies on bacterial filaments49. Cells were gently scraped from the electrode surface using a plastic spatula and isotonic wash buffer (4.35 × 10−3 M NaH2 PO4 ·H2O, 1.34 ×10−3 M KCl, 85.56 ×10−3 M NaCl, 1.22 × 10−3 M MgSO4 ·7H2O, and 0.07 × 10−3 M CaCl2 ·2H2O), then collected by centrifugation and re-suspended in 150 × 10−3 M ethanolamine (pH 10.5). Filaments were mechanically sheared from the cell surface using either vortexing for 1 min or a Waring Commercial Blender (Cat. No. 7011S) at low speed for 1 min, and then cells were removed by centrifugation at 13,000 x g before collecting filaments with an overnight 12.5% ammonium sulfate precipitation and subsequent centrifugation at 13,000 x g for 60 minutes. Collected filaments were re-suspended in ethanolamine buffer and further purified by centrifugation at 23,000 x g to remove debris and a second 12.5% ammonium sulfate precipitation with centrifugation at 13,000 x g14. The final filament preparation was re-suspended in 200 µl ethanolamine buffer. Filament preparations were further passed through 0.2 μm filters to remove any residual cells and stored at 4 °C. The pH of the buffer was equilibrated using HCl as previously described7. Cell-free filament preparations were imaged first with transmission electron microscopy to ensure sample quality.

Cell and protein normalization for comparative expression studies.

Bacterial strains were grown to late exponential phase (OD600 ~0.6–0.7) unless specified. For filament preparations, strains were normalized to the initial wet weight of the bacterial pellet. All the steps were performed in parallel and special care was taken to ensure that at each step the pellets were resuspended in same volumes across the strains. Equal volumes (1/20th of the final filament preparation protein) was loaded on the gels for comparison. Additional care was taken to collect the samples at a similar growth phase and optical density when comparing different strains.

SDS-PAGE.

For polyacrylamide gel electrophoretic separation (SDS-PAGE), the samples were boiled in 2.5% sodium-dodecyl sulphate (SDS) sample buffer that included β-mercaptoethanol for 12 min. The samples were run on a 4–20% gradient protein gel (Biorad, Hercules, CA) at a constant voltage of 200 V for 30 minutes. Precision Plus Protein Prestained molecular weight standards (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and Low Range Protein Ladder (Thermo Scientific) were used to compare the molecular weight of cytochromes in the filament preparations. Gels were immediately washed at least 3 times with ultra-pure deionized water over a 1-hour period, stained with Coomassie R-250 stain (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL), and destained overnight.

Immunoblotting.

Custom polyclonal anti-OmcZ antibody was synthesized by LifeTein (New Jersey) by immunizing two rabbits with synthetic peptide sequence (DSPNAANLGTVKPGL) containing targeted epitope on the native protein, OmcZ, and then affinity purifying the serum against that peptide sequence. The antibody was used at a dilution of 1:5000 for immunoblotting. Filament preps were normalized to the initial cell mass of the starting material.

Mass spectrometry.

For LC-MS/MS analysis of filament preparations, the OmcZ band (~30 kDa) was excised from the gel and treated with chymotrypsin to digest the protein. Proteomic analysis of the cleaved peptides from filaments was performed by the Keck Facilities at Yale University. Unique amino acid sequence matches with the OmcZ were found (Extended Data Fig. 2c,d). For quantification of OmcZ in filament preparations, the “top three” method50,51 was employed by quantitating the three peptides with highest intensity52 (Extended Data Fig. 2f). Previous study has confirmed that OmcZ contains 8 hemes through intact mass spectrometry and pyridine hemochrome assay8.

Estimation of molecular weight of OmcZ nanowires using Cryo-EM.

Mass of the protein (M in kDa) is proportional to its volume due to the fact that most of proteins have intrinsically similar density ~1.35 g/cm3(V in Å3)53. Therefore, M1/M2=V2/V1 where M1 and M2 are the masses for the respective proteins and V1 and V2 are their volumes. For OmcS4, M1 = 47 kDa and V1 is computed from the helical parameters as follows: The axial distance between two subunits called rise is 46.7 Å and the axial distance between one helical turn called pitch is 200 Å. Therefore, OmcS nanowire has 200/46.7 = 4.28 subunits per helical turn. Volume of OmcS filament per helical turn is approximated by πr2L where r is the radius of OmcS filament (35/2=17.5 Å) and L is the length (200 Å) which gives volume 192,423 Å3. As there are 4.28 subunits per turn, the volume of OmcS subunit (V1) is 192,423/4.28 = 44,959 Å3.

For 2.5 nm-diameter filament, the helical rise is 57 Å and pitch is 128.25 Å, giving 128.25/57=2.25 subunits per turn. Volume of these filaments per helical turn using the same equation is πr2L where r is the radius of filament (25/2=12.5 Å) and L is the length (128.25 Å) which gives volume 62,954.7 Å3. As there are 2.25 subunits per turn, the volume of the subunit (V2) is 62,954.7/2.25 = 27,980 Å3. Therefore, using the relation M2= M1 x V2/V1, the estimated mass of the protomer of these filaments is 27,980 x 0.001 = 28 kDa which is close to molecular weight of 30 kDa for extracellular form of OmcZ8.

AFM sample preparation.

Prior to all measurements, nanowires were imaged with AFM and height measurements were performed to confirm the presence of individual nanowires and to confirm their identity. IR s-SNOM measurements were also performed on bundles of OmcS nanowires under high pH conditions (pH ≥ 7). These nanowires did not show any β-sheets and the results were similar to individual OmcS nanowires showing primarily α-helix as secondary structure, confirming that low pH conditions are necessary to induce the formation of β-sheets in OmcS nanowires.

For imaging with AFM or combined AFM and IR s-SNOM or conducting-probe AFM, 20 µl buffer containing nanowires was drop casted onto appropriate substrates. Freshly cleaved mica (Muscovite Grade V1, SPI supplies) was used for topography imaging only whereas template-stripped gold surface (Platypus, AU.1000.SWTSG) was used for IR s-SNOM and nanoelectrode gold array was used for conducting-probe AFM. Except mica, all substrates were plasma cleaned for 10 minutes under medium plasma exposure and washed with DI water (Fig. 2a). For bulk FTIR, Raman, circular dichroism (CD), XRD and fluorescence emission spectroscopy, nanowires were directly measured in their native buffer environment. Conformation change at pH 2 in the films of OmcS nanowires in Citrate buffer was similar to Phosphate buffer (Extended Data Fig. 9d–f). Therefore, the Citrate buffer was used for height analysis of OmcS nanowires.

Immunogold labelling of OmcZ nanowires.

Transmission electron microscopy-based immunogold labelling was performed as described previously10. In brief, samples of purified extracellular filaments were adsorbed to plasma-cleaned carbon film-coated copper grids (400 mesh, Electron Microscopy Sciences) and incubated for 5–10 min. Samples were subsequently treated with 0.1% glutaraldehyde (supplied as 2.5% Glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sorensen’s Sodium-Potassium Phosphate Buffer, Electron Microscopy Sciences, and diluted in a 0.2 M solution of the same buffer) followed by rinsing with a Sorensen’s buffer solution (0.2 M, pH 7.2, Electron Microscopy Sciences). The grids were then treated for 15 minutes with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) dissolved in Sorensen’s buffer, followed by 30 min to 2 hr incubation with either the monospecific anti-OmcZ antibodies developed for this study (LifeTein, New Jersey) or the previously described peptide-based rabbit-derived polyclonal antibodies against OmcZ8; for these primary antibody incubations the antibodies were diluted 1:50 in Sorensen’s buffer containing 0.3% BSA. Grids were then rinsed three times in Sorensen’s buffer solution and incubated for 30 min to 1 hr with goat-derived polyclonal secondary antibodies conjugated to gold nanoparticles (6 or 12 nm Colloidal Gold AffiniPure Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) (EM Grade), Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.). Grids were then rinsed three times in Sorensen’s buffer solution and negatively stained with 1% phosphotungstic acid (pH 6.8) for 15 to 30 s and subsequently air-dried. Finally, grids were examined using a JEOL JEM-1400 Plus transmission electron microscope operated at 80 kV. Immunogold samples imaged via AFM (Extended Data Fig. 3a) were prepared as above, except that samples were adsorbed to a mica substrate rather than TEM grids, and no negative staining solution was applied.

Bacteriorhodopsin (bR) preparation.

bR from Halobacterium salinarum (Sigma Aldrich B0184, native sequence, lyophilized powder) was diluted to a stock concentration of ~150 µg/ml in 0.01% sodium azide (NaN3). Adsorption buffer (20 µl, 150 mM KCl + 10mM Tris/HCl at pH 7.4) was drop casted onto the gold surface and 20 µl of stock bR were added to the droplet. After ~30 minutes, the sample was rinsed with deionized water.

Lysozyme preparation.

Lysozyme was purified from chicken egg white (Sigma Aldrich L7651) and dissolved in 10 mM potassium phosphate (KH2PO4) buffer at pH 7 (final concentration ~200 µg/ml). The lysozyme sample was prepared similar to the procedure described above for bR.

AFM of nanowires and other proteins.

AFM experiments for height measurements were performed using soft cantilevers (AC240TSA-R3, Oxford Instrument Co.) with a nominal force constant of 2 N/m and resonance frequencies of 70 kHz. The free-air amplitude of the tip was calibrated with the Asylum Research software and the spring constant was captured by the thermal vibration method. Samples were imaged with a Cypher ES scanner using intermittent tapping (AC-air topography) mode. All nanowires height analyses and statistics were performed using Gwyddion and IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Inc.). To check protein quality for infrared nanospectroscopy, AFM was performed using cantilevers (Arrow-NCR, Nano Worlds) with a nominal force constant of 42 N/m and a resonance frequency of 285 kHz. Samples were imaged with an Icon AFM (Bruker) using intermittent tapping (AC-air topography) mode. Liquid AFM was performed using bio-lever mini tips (BL-AC40TS, Olympus) with resonance frequency of 25 kHz in liquid and nominal force of 0.1 N/m. AFM images were processed using the Gwyddion package.

Nanoelectrode design and fabrication.

Electrodes made of gold separated by a non-conductive gap (Fig. 3a) were designed using electron beam lithography. Interdigitated electrode devices were designed in Layout Editor, a computer-aided design program. The electrodes were patterned by electron-beam lithography on a sacrificial electron beam resist layer spin coated onto a 300 nm layer of insulating silicon dioxide (SiO2) grown on a silicon wafer. The wafer was then developed in a solution of cooled isopropyl alcohol to remove the resist layer where the pattern was printed. A 30-nm-thick gold film was evaporated after a 5-nm-thick titanium adhesion layer on lithographically patterned wafer using an electron-beam evaporator (Denton Infinity 22). The electron beam resist was removed with N-Methyl-2pyrrolidone by incubating for 15–20 min at 80 °C until the lift-off was complete. The device was then rinsed sequentially with acetone, methanol, and isopropanol before being dried with nitrogen, resulting in gold nanoelectrodes with a non-conductive gap (Fig. 3a). All device fabrication was performed in a class 1000 cleanroom to avoid contamination. The devices were further inspected with optical and scanning electron microscopy to ensure that the electrodes are well separated by a non-conductive gap, and resistance measurements were used to confirm that the electrodes are well insulated from each other (Rgap > 1 TΩ). Before usage, the device was washed with distilled water and then rinsed with isopropanol to remove contaminants on the surface. The device was further cleaned for 1 min with oxygen plasma and dried with nitrogen flow.

IR s-SNOM on individual proteins.

As described previously18, we used IR radiation from a wavelength-tunable quantum cascade laser (Daylight Solutions MIRcat Amide QCL tunable from 1450–1700 cm−1 with a bandwidth < 1 cm−1 and spectral resolution of 0.25 cm−1) to illuminate a conductive AFM tip with < 20 nm spatial resolution (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b). We incorporated this IR-coupled AFM to one arm of a Michelson interferometer and focused the IR laser to the AFM tip apex with a parabolic mirror (Numerical Aperture=0.25 and Power < 10 mW) (Extended Data Fig. 5a). We used conductive PtSi (PtSi-NCH, Nanosensors)∼ with a tip radius of 20 nm operating in tapping mode (resonance frequency ωt ~ 330 kHz). We operated the interferometer in 2-phase homodyne mode for IR s-SNOM19 to isolate and amplify the near-field, tip-scattered signal from the far-field background. We tuned the laser from 1600 cm−1 to 1700 cm−1 in 5 cm−1 steps and recorded images at each wavenumber to obtain the amide I spectra using IR s-SNOM. IR s-SNOM phases describe absorption properties. For background subtraction, we obtained the phases from the sequential images from the empty region on the gold substrate (Extended Data Figures 5–6)19.

The tip-scattered IR radiation was recombined with the reference field for 2-phase (Փ1 and Փ2 in Extended Data Fig. 5a) homodyne amplification and detection with a HgCdTe detector (Kolmar Technologies). Far-field background was suppressed by demodulating the detected signal with lock-in amplifier (Zurich Instruments, HF2LI) at third harmonic of the cantilever oscillation frequency (3ωr) except for bR that used 3ωr+Ωr where Ωr is the frequency of the chopper used in the reference arm19. This modulation scheme isolated the near-field signal and provided the background-free near-field phase ϕ. Extracted near-field phase signals were used to access the absorptive properties of imaged proteins. Raster scanned s-SNOM images were acquired with a lock-in time constant of 10 ms/pixel that yielded good near-field signal contrast and avoided sample drift. The signal from the gold was at least 10 times lower than intrinsic protein signal, ensuring a high signal-to-noise ratio to extract the protein structure. All IR s-SNOM analyses and statistics were performed using Gwyddion software (Figures 2,5 and Extended Data Figures 5–6). To extract near-field phase (absorption) properties of proteins, we used a two-phase homodyne detection technique by changing the reference arm between two orthogonal known phase components such as Φ1 = Φ2+π/2 and extracted near-field phase signal using following relations18,19:

Deconvolution and peak fitting of amide I spectra for IR s-SNOM and bulk FTIR.

Band decomposition analysis was performed using a multi-peak fitting analysis program (IGOR Pro, WaveMetrics, Inc.). IR s-SNOM spectra were evaluated with Lorentzian line shapes19 and bulk FTIR spectra were evaluated with Gaussian line shapes20. For IR s-SNOM of nanowires, bR, and lysozyme, data are represented with red markers. Fitting results (blue curves) were obtained by applying band-decomposition analysis to the data, which yielded good agreement (χ2 <0.02). Areas under the curve were integrated to estimate the percentages of α-helix, β-sheet, and coil components (Supplementary Table 1a for lysozyme and Supplementary Table 1b for OmcS and OmcZ nanowires). In amide I mode, α-helices give rise to main absorption band located at 1660 cm−1. β-sheets show a stronger band at 1625 cm−1 and a weaker band near 1685 cm−1, ~60 cm−1 away from the stronger band17. This observed splitting in the β-sheet formation arises due to the transition dipole coupling mechanism17. The formation of β-sheets in IR s-SNOM spectra for OmcS and OmcZ nanowires was evident from the presence of these two β-sheet bands17 (Fig. 5d,e). All analyses were performed using IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Inc.).

Conducting-probe atomic force microscopy (CP-AFM) measurements.

To measure the conductivity of nanowires using CP-AFM, 5 µl of ethanolamine buffer solution containing nanowires were deposited on gold electrodes patterned with electron-beam lithography on a silicon wafer grown with 300 nm silicon dioxide as described above. The excess buffer was absorbed with filter paper. After air-drying, the sample was mounted on a metal puck and transferred to the sample stage inside the AFM (Oxford Instrument Co., Cypher ES). AFM and subsequent CP-AFM experiments were performed using soft cantilevers (ASYELEC-01, Oxford Instrument Co.) with a nominal force constant of 2 N/m and resonance frequencies of 70 kHz. The tip was coated with Pt/Ir. The free-air amplitude of the tip was calibrated with the Asylum Research software and the spring constant was captured by the thermal vibration method. For CP-AFM experiments, the dual gain ORCA holder was used (Asylum Research) to record both low and high current values. The sample was imaged with a Cypher ES scanner using intermittent tapping (AC-air topography) mode. AFM showed that gold electrodes were partially covered with nanowires to facilitate CP-AFM measurements (Fig. 3a). After identifying OmcZ nanowires across the electrodes and the substrate, the tip was withdrawn and brought into contact with the nanowires by switching on the contact mode. Points along the length of the nanowires were selected based on the AFM image (Fig. 3a) and the corresponding distance was measured with Asylum Research Software that is used to operate AFM. With partially gold-coated substrate as the first electrode and a metal-coated AFM tip as a second mobile electrode, the uncovered parts of the nanowires were electrically contacted, measuring the I-V characteristics as a function of the distance between the tip and the electrode by applying a bias ramp in the range −0.2 V to + 0.2 V (Fig. 3b), and then the tip was withdrawn to the next point. To verify proper electrical contact during the measurements, the tip was frequently brought into contact with either gold or SiO2 substrate (Supplementary Fig. 2). A loading force of 50 nN was used to obtain stable current and the same force was used for all experiments reported in this manuscript. The I-V characteristics were captured in the software and the analysis was performed in IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Inc.). I-V curves were processed using 75 points Savitzky-Golay smoothing function prior to fitting using IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Inc.). The linear regime of the I-V characteristics was used for calculation of resistance using the equation: R=V/I. The resistance from different points was then plotted as a function of distance (L) (Fig. 3c). For each distance, at least 8 repeats were recorded and a minimum of three biological replicates were used to evaluate statistical significance (Fig. 3c–d).

Conductivity calculations.

The conductivity (σ) of nanowires (Fig. 3d, 5b) was calculated using the relation σ = G∙(L/A) where G is the conductance measured previously14, which is reciprocal of resistance R, L is the length of the nanowire, and is the area of cross section of the nanowire with 2r as the height of the nanowire measured using AFM, taking into account pH-induced reduction in diameter (Fig. 5a, Extended Data Fig. 4). Due to the extremely small (~3 nm) height of the nanowires, the small cross-sectional area of the nanowires gives rise to higher conductivity. Note that these height-corrected values (Fig. 5b) are a lower estimate for the conductivity of individual nanowires compared to that measured directly using conducting-probe AFM (Fig. 3d).

As our W51W57 cell growth and filament preparation conditions were similar to previous studies14, our results suggest that the nanowires reported to be tryptophan-substituted pili14 are OmcZ nanowires and hence were used for conductivity comparison with OmcS (Fig. 5b).

Stiffness measurements.

The OmcS and OmcZ nanowires were prepared for stiffness measurements in a manner similar to AFM sample preparation described earlier. Samples were imaged with a Cypher ES scanner using amplitude-modulation (AM)-frequency modulation (FM) bimodal imaging mode using Arrow UHFAuD (Nanoworld) cantilever with 6 N/m nominal force constant (k1). The spring constant for both the first and second eigenmodes (k1 and k2) and the quality factor (Q) of the tip was calibrated by fitting the thermal vibration curves before the experiment. To operate in bimodal AM-FM imaging mode, the tip was tuned on both eigenmodes prior to tip sample interaction. Tuning of the cantilever was modulated with the blue drive aligned to the base of the cantilever to produce maximum driving power. The first cantilever eigenmode was excited to the resonant frequency (f1 ~2 MHz) and tuned with the AFM software (Asylum Research) and the second eigenmode was excited to the second order resonant frequency (f2 ~7 MHz) at least ~100 times lower in amplitude than the first eigenmode.

Upon approaching the sample, the tip was final tuned to compensate for the shift in drive frequency induced by tip-sample interaction. Repulsive imaging mode was used (phase < 90°) to overcome adhesion force. Drive amplitude was adjusted to maintain a small indentation depth (~300 pm) and the maximum indentation δ depth was monitored from the imaging feedback loop using the following relation:

where A1,free is the free amplitude tuned for the first eigenmode, ϕ1 is the phase response of the first eigenmode, and Δf2 is the frequency shift monitored from the second eigenmode. The effective storage modulus of the interaction Eeff was calculated from the following equation using a Hertz punch model59:

where A1,set is the setpoint used for imaging and R (~7 nm) is the tip radius provided by the manufacturer. Correlated topography and Young’s modulus images were generated with a resolution of 512 x 512 pixels (Extended Data Fig. 8). The mean value of the nanowire modulus was extracted by fitting a Gaussian function to the histograms created from the modulus map of three biological replicates (Extended Data Fig. 8). The same tip and imaging configuration were used for all samples to maintain consistency between measurements.

Grazing-incidence X-ray microdiffraction (GIμXRD).

To visualize the stacking of hemes in nanowires and to investigate the effect of pH on the stacking, GIμXRD data were collected in grazing incidence mode using a Rigaku D/Max Rapid II instrument equipped with a 2D image plate detector. The Aro5 strain was used to focus on OmcS nanowires whereas W51W57 strain was used to probe OmcZ nanowires. X-rays were generated by a MicroMax 007HF generator fitted with a rotating chromium anode (λ= 2.2897 Å) that was focused on the specimen through a 300 µm diameter collimator. The instrument’s correct sample-to-detector distance was verified by measuring the lattice constant of a LaB6 standard (NIST 660c). All nanowire samples were prepared using a centrifugation method without salts for precipitation7, such as ammonium sulphate, to eliminate background peaks (Fig. 4a–b). Samples were then dialyzed in 150 mM ethanolamine buffer at pH 10.5 and 20 μl solutions containing nanowire samples were dropped from a micropipette onto glass substrates. To ensure data reproducibility, the experiments were repeated at multiple spots that yielded similar results. At least three different surface spots were scanned at a fixed 1° incident angle with no sample rotation in the sample plane. These multiple measurements yielded similar results. To further investigate the pH effect on the stacking, the pH of nanowire sample was changed by applying ethanolamine buffer at pH 7 and pH 2 (Fig. 4a–b). The background was subtracted using smoothing procedure used for XRD data60 and the data was plotted using IGOR Pro (WaveMetrics, Inc.). Rigaku’s 2D Data Processing Software (Ver. 1.0, Rigaku, 2007) was used to integrate the diffraction rings captured by the detector. Peak fitting to determine d-spacings was carried out using JADE 9.5.1 (Materials Data, Inc.) with the Pseudo-Voigt peak profile function.

FTIR.

We used the Agilent Cary 660 FTIR with a Pike Technologies GladiATR™ single reflection attenuated total reflection geometry with a diamond crystal. All FTIR spectra were collected with spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Final spectra represent an average of 144 individual spectra and are plotted as absorbance versus a background of air. Samples were prepared on a silicon wafer and the reference spectrum of 10 mM KPO4 was subtracted from the nanowire spectra. An ATR correction and boxcar smoothing were applied using Agilent software (Extended Data Fig. 9a–c). Measurements on air-dried films were compared to samples fully hydrated in D2O, which eliminates the strong H2O IR absorption in the amide I band; these measurements were found to be equivalent (Extended Data Fig. 9c).

Raman spectroscopy.

Raman spectroscopy was performed using a 532 nm-green solid-state diode laser (continuous wave, power ~57 mW) with a synapse-cooled CCD detector, 600 grating/mm, and 50X objective (Horiba-Labram HR Evolution). Nanowires prepared in ethanolamine buffer were drop-casted on a silicon wafer. Data were collected with an accumulation time of 10 s, averaged over 80 iterations. A minimum of three different locations were measured on each sample. All experiments were repeated on multiple samples that yielded similar results. The instrument was calibrated using the silicon wafer as standard. Data were analysed with IGOR Pro software (WaveMetrics, Inc.).

CD spectroscopy.

CD spectra and subsequent analysis with CDPro were conducted to estimate the secondary structure fractions of OmcZ and OmcS nanowires. Samples were initially dialyzed in 10 mM KH2PO4 buffer at pH 7; the protein concentration was determined via the standard bicinchoninic acid assay. CD scans of nanowire samples and buffer background (five replicates) were collected between 190 nm and 260 nm with a 10- or 2-mm-pathlength quartz cuvette using a spectrometer (Chirascan, Applied Photophysics). Using the Pro-Data Chirascan software (Applied Photophysics), all replicate spectra were averaged, the averaged buffer background spectrum was subtracted from all averaged nanowire spectra. The following formula35 was used to convert raw ellipticity values (mdeg; millidegrees) (Fig. 6c,d) to molar ellipticity values ([θ]; deg cm2 / dmol) for secondary structure quantification shown in Supplementary Table 1c:

Fluorescence microscopy of nanowires.

A 600 µM Thioflavin T (ThT) stock solution was used to bring nanowire solutions to a final concentration of 100 µM ThT. Samples were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature before depositing 10 µl of solution on cleaned microscope slides and coverslips. Microscope slides (Fisherfinest Premium Catalogue No. 12-544-1) and coverslips were sonicated for 20 minutes each in 1 M KOH, Milli-Q water, and finally 70% ethanol before they were air-dried with nitrogen. Control samples that had only ThT or only nanowires did not show any fluorescent fibril structures (Fig. 6e), confirming that the observed fluorescence is due to ThT binding to nanowires. Samples were excited with a 445-nm CW laser (Agilent Technologies MLC 400B) used at 30% of maximum power (<10 mW). TIRF microscopy images were acquired on an Eclipse TiE microscope (Nikon) equipped with an Andor iXonEM+ DU-897 camera. All images were processed and analysed using ImageJ software.

Fluorescence emission spectroscopy of nanowires.

Thioflavin T (ThT) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich; 600 µM stock solutions were prepared by diluting ThT in 10 mM KPO4 at pH 7, passing the solution through a 0.2 µm filter to remove dye aggregates, and verifying the final ThT concentration with UV-vis spectroscopy and the ThT extinction coefficient of (36,000 M−1 cm−1 ) at 412 nm. Nanowire samples were diluted at a 1:1 ratio (v/v) with a solution of 100 µM ThT and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour before acquiring spectra with a Fluoromax-4 spectrofluorometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon) in an ultra-micro fluorescence cuvette with an optical path length of 10 mm (PerkinElmer Part No. B0631124). The excitation wavelength was set to 440 nm and emission was recorded at 465–600 nm with 5 nm excitation and emission slit widths.

Modelling of OmcZ:

We modelled the OmcZ monomer using both homology modeling and de novo folding because multiheme cytochromes such as OmcZ have very low sequence identity with other multiheme cytochromes4. A BLAST search found only five unique matches to OmcZ, with the top match being the sixteen-heme cytochrome (PDB ID: 1Z1N) having a sequence identity of 24%. However, this cytochrome had cross-like heme arrangement with only a single parallel-stacked heme pair, whereas the X-ray diffraction studies of OmcZ (Fig. 4a) indicated several parallel pairs. Additionally, we found two proteins with higher sequence identities to OmcZ of 29% (3ON4) and 36% (1ZYE), but neither of these contained hemes, making them unusable as templates. The two remaining matches, (PDB IDs: 6H5L and 4QO5), were both octaheme protein complexes structurally similar to hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO), although they had low sequence identities with OmcZ of 21% and 24%, respectively. From previous CD measurement of purified OmcZ8, OmcZ is known to have an unusually high amount of beta sheets, around 25%, and contained few alpha helices, only 13%. Comparatively, 4QO5 was only 8% beta sheets and 40% alpha helices, and 6H5L is 2% beta sheets and 66% alpha helices. A search of other similar octaheme proteins in the Protein Data Bank revealed that they can be divided into two classes: HAO-like proteins and OTR-like (Octaheme Tetrathionate Reductase) proteins. These two classes of octaheme cytochromes had distinct, well-conserved heme arrangements. In addition to alternating parallel and T-stacks, HAO-like proteins have a triple parallel stack between the fourth, sixth, and seventh hemes in which two hemes (the fourth and seventh) are coplanar and the remaining sixth heme is stacked atop both. The fourth heme is out of line with the other seven hemes and is often ligated by a small molecule, such as water or SO2, or by amino acids like lysine. OTR-like cytochromes have a similar overall arrangement but the triple parallel stack is formed earlier in the heme sequence (the second, fourth, and fifth hemes), such as in structures with PDB IDs:1SP3 and 4RKM. Therefore, templates for our OmcZ model were chosen based on these two primary heme arrangements (HAO and OTR) and to match the high amount of beta sheets found in purified OmcZ8. The two templates that best satisfied these criteria were HAO-like 4QO5 and OTR-like 1SP3. Both templates, as well as the other octaheme proteins, had sequences much longer than OmcZ leading to some of the extraneous structure from the templates being excluded from the models, such as the alpha helix cluster in the 4QO5. Alignment with the templates was restricted such that the heme-binding CXXCH sequences matched between both the template and OmcZ to enable the binding of hemes in the model. After the initial structure was built in MODELLER, unbound histidine residues were reoriented in order to bond to the iron center as the hemes’ distal ligands. A unique feature of OmcZ was the three pairs of neighboring histidine residues (H40 & H41, H96 & H97, and H182& H183) in the protein sequence. Using these histidines as ligands between the T-stacked hemes, protein was found to hold hemes in a rigid conformation and closer than typical T-stacks. This could explain the higher heme stacking found in OmcZ (Fig. 4a). Unfolded peptide segments between hemes were refined using the de novo folding procedure in MODELLER.

To fold the long loops in both models, we carried out long timescale classical MD simulations on Anton-2. We first equilibrated each system in a periodic water box for 100 ns using nanoscale molecular dynamics (NAMD)heme and the CHARMM36 force field. We then performed 2-µs simulations using both the 1SP3- and 4QO5-based models. The 1SP3 model appeared to break between hemes 4 and 5 (a T-stack) and fold in half. The 4QO5 model was more stable even though the distance between parallel stacks (hemes 1/2, 3/5, and 6/7) increased significantly as the protein extended and pulled the hemes apart. Therefore, this model was chosen to build the model of OmcZ.

For final model building, we used the fact that many 8-heme proteins show similar stacking arrangement of hemes25 as shown in the superposition of heme groups from five HAO-like proteins (Extended Data Fig. 7b, PDB IDs: 4QO5:Green, 1FGJ:Blue, 3GM6:Cyan, 6H5L:Gray, and 6HIF:Pink). The 4QO5 structure was used as the reference for alignment and overlay was performed by minimizing the RMS distance between the respective hemes’ iron centers using the pairwise fitting function within PyMOL. Adding harmonic restraints to the hemes and performing another 2-µs simulation of the 4QO5-based model, we obtained the folding of the protein without the hemes pulling apart. One region appeared to fold into beta sheet-like structures that did not resolve further with longer simulations. MODELLER was used to add formal structure to the regions that seemed to be approaching beta sheets and alpha helices (Extended Data Fig. 7a). We aligned the hemes from each OmcZ model to the low-resolution (20 Å) cryo-EM density map. To refine the fit, we simulated a density map of the hemes with 15 Å resolution using the MDFF plugin in VMD. The highest density in the cryo-EM density map is typically contributed by the hemes4. We confirmed this by comparing the alignment of simulated heme density to the high-density components of our 3.7 Å resolution cryo-EM density map of OmcS. Therefore, the computed density map was compared to the cryo-EM density map filtered to high density (Extended Data Fig. 7c,d).

Building a model for OmcZ was hampered by following challenges. First, a crystal structure is not available. A model could not be determined by cryo-EM. The flexibility of OmcZ and its tendency to form bundles of fibers have severely limited collection of the large number of straight single filaments required for ab initio atomic model building. These challenges have resulted a low resolution (~ 20 Å) map that was used for comparison (Fig. 4d).

In the absence of an experimental structure, computational modeling relied on one of two methods to build a model: homology modeling and ab initio folding. The eight hemes bound within OmcZ severely complicate ab initio folding, if not making it entirely impossible using currently available methods. These hemes are not small ligands bound to an active site; they take up a significant volume at the core of OmcZ and are undoubtedly critical to its structure. Using a sequence homologue as a template for homology modeling is also not feasible. The best amino acid sequence matches were very weak (less than 25% identity), several contained no hemes, and most primarily consisted primarily of alpha helices whereas OmcZ contains beta sheets.

However, our OmcZ model does include key features consistent with experiments. First, the family of octaheme c-type cytochrome proteins shares a highly conserved heme arrangement that seems similar to seen at the core of OmcZ using high-contour cryo-EM maps. Second, our model maximizes the amount of beta sheets, as indicated by experiments.

The amino acid sequence of OmcZ contains 8 hemes with total 17 histidines, including three pairs of adjacent histidine residues distributed across the sequence (H40 & H41, H96 & H97, and H182& H183). Assuming all hemes in OmcZ are bis-histidine coordinated, a minimum of 16 histidines will be required for axial ligation to 8 hemes. Therefore, these adjacent histidine pairs could be forming a heme ligation that would create a closely-held, rigid T-stacked heme pair. This consecutive His-His binding motif found in OmcZ also exists in c3 cytochromes (PDB ID: 1gyo, 2bq4, and 2e84). However, in OmcZ model, the three pairs of adjacent histidines that bind to T-stacked hemes are all distal histidine ligands. Therefore, they are bound opposite to the proximal histidine in the CXXCH sequence. In contrast, in the c3 cytochromes, all the heme-binding adjacent histidine pairs are mixed, containing both a proximal and a distal histidine. Despite this difference, the distance between the bound hemes remains consistent at ~6 Å (Extended Data Fig. 7e–h). This analysis thus further validates our modelling approach.

Statistics and Reproducibility.

All imaging and measurements were repeated at least over three biological replicates and yielded similar results.

Data Availability.

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability.

The codes used during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Extended Data

Multimodal imaging and nanospectoscopy platform to determine the structure of individual OmcZ and OmcS nanowires as well as their electrical and mechanical properties.

a, Multimodal platform with OmcS nanowire structure showing stacked haems providing electron transport path (PDB ID: 6EF8). b-c, OmcZ nanowires produced by ΔomcS strain grown under conditions that overexpress OmcZ. b, AFM images of OmcZ nanowires of ΔomcS strain. c, Zoomed image of OmcZ nanowire shown in white square in b. d, AFM Height profile of the OmcZ nanowire taken at the a location shown by a red line in c. Scale bars: b, 100 nm c, 20 nm.

Mass spectrometry and immunoblotting of filament preparations confirm electric field induces overexpression of OmcZ in biofilms.

a-b, Strategy to evaluate the effect of an electric field on the production of OmcZ nanowires. Wild-type G. sulfurreducens cells were grown with a continuous supply of fumarate on graphite electrodes as anodes in a microbial fuel cell. a, An electric field was supplied during the growth of current-producing biofilms by connecting anode to cathode via a potentiostat. b, The electric-field was absent after disconnecting the anodes from the cathodes. OmcZ peptide coverage (blue) in filament preparations of c, Wild-type (WT) and d, W51W57 strain confirming the presence of an extracellular (30kDa) form of OmcZ that forms nanowires. Comparison of OmcZ abundance in filament preparations of WT and W51W57 strains using e, Immunoblotting and f, Mass spectrometry showing higher level of OmcZ in W51W57 strain than WT. Data represent mean ± standard deviation (n= 3 biologically independent samples overlaid as black circles).

Immunogold labelling confirms the identity of OmcZ nanowires.

a, AFM image of immunogold-labelled OmcZ nanowire. b, heights of nanowire (red) and gold nanoparticle (blue) at locations shown in a. c-f, TEM images of OmcZ nanowires of ZKI strain in the c, absence of OmcZ antibody and d, in the presence of anti-OmcZ antibody. Secondary antibody with gold nanoparticles was used in both c and d. e, No OmcZ labelling was found for filaments of ΔomcZ strain f, Labelling for OmcZ nanowires of W51W57 strain. Scale bars, a, 100nm, c, 50 nm, d, 25nm, e, 100 nm, f, 25 nm.

Low pH reduces the diameter of individual OmcS and OmcZ nanowires.

Histograms of AFM measurements of OmcS and OmcZ nanowire heights showed that lowering the pH reduced the diameter of a, OmcS and b, OmcZ nanowires. Values represent mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) (n=100 measurements of nanowires over 3 biologically independent samples).

IR s-SNOM imaging of bacteriorhodopsin (bR) confirms α-helical structure.

a, b Schematic of IR s-SNOM. a, The interferometer is comprised of a tunable quantum cascade laser (QCL) for tip illumination, a beam splitter (BS), a detector (Mercury Cadmium Telluride, MCT), a parabolic mirror (PM), and a reference mirror. b, Schematic of the IR s-SNOM setup used for bR imaging (PDB ID: 1m0l). All helices are parallel to electric field lines that enhance the amide I signal. c, AFM topography and corresponding height profile for bR taken at a location shown by a black line. d, IR s-SNOM near-field phase (absorption) images for bR at various IR excitations. At 1660 cm−1 (iii, on-resonant IR), the amide I absorption is enhanced in the near-field phase data. However, when changed to other frequencies (i-ii & iv-v, off-resonance), the phase signal decreases and drops to zero. e, Spatiospectral analysis of near-field phase data for the amide I mode of bacteriorhodopsin. The blue line corresponds to a fit of the imaginary part of a Lorentzian (Lor) with peak at 1663 cm−1 and line width of 25 cm−1. Data represent mean ± standard deviation for individual bR proteins (n= 3 biologically independent samples).

Bulk FTIR and IR s-SNOM confirm lysozyme structure and IR s-SNOM spectroscopy of OmcS nanowires agrees with Cryo-EM structure.

Multi-peak fitting function was used to fit the data using a, Gaussian profile for bulk FTIR and b, a Lorentzian profile for IR s-SNOM data. α-helix corresponds to 1662 cm−1, β-sheet corresponds to 1618 cm−1 and 1678 cm−1, and the loop (D) region corresponds to 1635 cm−1. c, Schematic of the IR s-SNOM setup for nanowire imaging. Secondary structure of the OmcS nanowire at pH 10.5 is shown in a (PDB ID: 6EF8) with α-helices in red, 310 helices in pink and beta strands in green. d, At pH 10.5 used to solve the structure of OmcS nanowires, spatiospectral analysis of near-field phase data of the amide I mode of OmcS nanowire. The blue line corresponds to a fit of imaginary parts of a Lorentzian, with peak positions at 1669 cm−1 and 1643 cm−1 corresponding to α-helical and loop regions respectively. Data represent mean ± standard deviation for individual OmcS nanowires (n= 3 biologically independent samples).

Model of OmcZ structure reveals highly stacked haems and beta sheets in agreement with experiments.

a, Computational model of OmcZ. b, Superposition of haems from five 8-haem cytochromes (PDB ID:4QO5:Green, 1FGJ:Blue, 3GM6:Cyan, 6H5L:Gray, and 6HIF:Pink). Both c, computed and d, experimental cryo-EM density for OmcZ show similar shape and size. e-h, Consecutive histidines cause tight haem T-junction. The His-His binding motif found in OmcZ also exists in c3 cytochromes, (PDB ID: e, 1gyo, f, 2bq4, and g, 2e84). In OmcZ model (h), the three pairs of adjacent histidines that bind to T-stacked haems are all distal histidine ligands bound opposite to the proximal histidine in the CXXCH sequence. In the c3 cytochromes, all the haem-binding adjacent histidine pairs are mixed, containing both a proximal and a distal histidine. Despite this difference, the distance between the haem pairs for c3 and OmcZ is similar (~6.0 Å).

Reduction in nanowire diameter enhances their stiffness.

AFM topography, Young’s modulus, and the stiffness distribution for OmcS nanowires at a, pH 7 and b, pH 2 and for OmcZ nanowires c, pH 7 and d, pH 2. Scale bars: a and d, 100 nm; b and c, 200 nm. Values represent mean ± (s. d.) for n=512 x 512 measurements of nanowires over threebiologically independent samples.

Bulk FTIR spectra of OmcS and OmcZ nanowires show transition to β-sheets at pH 2 and conformation change is independent of buffers.

FTIR spectra at pH 7 and pH 2 for a, OmcS nanowires and b, OmcZ nanowires showing a red shift, consistent with transition to β-sheets. c, Water does not contribute to the amide I spectra because OmcS nanowires at pH 7 under air-dried and D2O conditions display similar spectra. d-e, OmcS nanowires at pH 7 and pH 2 in 10 mM Potassium Phosphate and 20 mM Citrate buffer characterized by d, Solution CD spectra and e, Solid-state CD spectra. f, FTIR spectra for OmcS nanowires in Citrate buffer at pH 2 showing a red shift, consistent with transition to β-sheets. g, Representative AFM image and h, corresponding height profile at a location shown by a red line in g for OmcS nanowires in citrate buffer at pH 2 under air-dried conditions. Scale bar, 200 nm.

Purified OmcS and OmcZ nanowires from ΔomcZ and KN400 strains respectively show conformational change to β-sheets similar to nanowires of wild-type and W51W57 strains.

SDS-PAGE gel of filament preparations showing a single band corresponding to a, OmcS purified from ΔomcZ strain and c, OmcZ from KN400 strain. Corresponding TEM images of b, OmcS and e, OmcZ nanowires. Scale bars, 400 nm. Solution CD spectra of c, OmcS and f, OmcZ is similar to CD spectra of OmcS and OmcZ nanowires purified from wild-type and W51W57 strains respectively (Fig. 6c–d). M1 and M2 represent nanowires sheared from cells by two different methods – vortexing (M1) and blending (M2).

Acknowledgments

We thank D. Lovley (University of Massachusetts, Amherst) and K. Inoue (University of Miyazaki) for providing strains and OmcZ antibody as well as E. Yan, E. Martz, F. Samatey, C. Salgueiro, C. Shipps and Y. Xiong for helpful discussions. We also thank C. Leang for providing the protocol for immunogold labeling, T. Gokus from Neaspec for help with nanoscale IR imaging and M. Shahid Mansuri, J. Kanyo and T. Lam for help with mass-spectrometry analysis. A portion of the research was performed using Environmental Molecular Sciences Laboratory (EMSL, Ringgold ID 130367), a Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility sponsored by the Office of Biological and Environmental Research. S.E.Y. thanks M. Raschke, J. Atkin and S. Lea for help with building the IR s-SNOM setup and C. Smallwood for help with bacteriorhodopsin sample preparation. We thank T. Walsh from Asylum Research for help with stiffness measurements. At Yale, we thank W. Gray from C. Jacobs-Wagner’s laboratory for help with fluorescence microscopy and Z. Wu from H. Wang’s laboratory for help with Raman studies. Computational work was supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research Grant FA9550-17-0198 (V.S.B.) and high-performance computing time from the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center and from the high-performance computing facilities at Yale as well as supercomputer time from the Extreme Science and Engineering Discovery Environment under grant no. TG-CHE170024 (A.A.). Anton 2 computer time was provided by the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center (PSC) through Grant R01GM116961 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Anton 2 machine at PSC was generously made available by D.E. Shaw Research. This research was supported by the Career Award at the Scientific Interfaces from Burroughs Welcome Fund (N.S.M.), the NIH Director’s New Innovator award no. 1DP2AI138259-01 (N.S.M.), the National Science Foundation (NSF) CAREER award no. 1749662 (N.S.M.). Research was sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency Army Research Office and was accomplished under Cooperative Agreement Number W911NF-18-2-0100 (N.S.M. and V.S.B). This research was supported by NSF Graduate Research Fellowship awards 2017224445 (J.P.O.). Research in the laboratory is also supported by the Charles H. Hood Foundation Child Health Research Award (N.S.M.) and The Hartwell Foundation Individual Biomedical Research Award (N.S.M.).

References

2

3

4

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

Methods-only References

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

Floating objects

Electric field stimulates production of OmcZ nanowires.

a, Schematics of microbial fuel cell for biofilm growth. Detailed setup is shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a. b, Immunoblotting showing comparison of OmcZ abundance in filament preparations of WT cells under three different growth conditions. c, Cryo-EM images of OmcS (black square) and OmcZ nanowires (red square). d, Zoomed images of OmcS and OmcZ nanowires at locations show in c. e, Cryo-EM projection (2D average) of OmcZ nanowire. f, AFM image of WT bacterial cell grown under electric field showing OmcZ nanowires with corresponding zoomed images of OmcZ nanowires at locations shown in green squares. g, AFM height profile of the OmcZ nanowire taken at a location shown by a red line in f. Scale bars, c, 20 nm, e, 5 nm, f, 200 nm, 50 nm, and 20 nm.

Infrared nanospectroscopy confirms OmcZ nanowires in biofilms grown under electric field.