- Altmetric

Programmable magnetic field-free manipulation of perpendicular magnetization switching is essential for the development of ultralow-power spintronic devices. However, the magnetization in a centrosymmetric single-layer ferromagnetic film cannot be switched directly by passing an electrical current in itself. Here, we demonstrate a repeatable bulk spin-orbit torque (SOT) switching of the perpendicularly magnetized CoPt alloy single-layer films by introducing a composition gradient in the thickness direction to break the inversion symmetry. Experimental results reveal that the bulk SOT-induced effective field on the domain walls leads to the domain walls motion and magnetization switching. Moreover, magnetic field-free perpendicular magnetization switching caused by SOT and its switching polarity (clockwise or counterclockwise) can be reversibly controlled in the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions based on the exchange bias and interlayer exchange coupling. This unique composition gradient approach accompanied with electrically controllable SOT magnetization switching provides a promising strategy to access energy-efficient control of memory and logic devices.

A major challenge of spintronics is achieving magnetic field free electrical control of magnetisation. Here, Xie et al. achieve perpendicular magnetisation switching in a CoPt alloy, breaking inversion symmetry by varying the composition of the alloy in the growth direction.

Introduction

Breaking the structural symmetries of nanomagnetic systems allows for physics that is forbidden in symmetric systems, promoting unique fundamental interactions between electrical current and magnetization. Especially, spin–orbit coupling (SOC) combined with inversion symmetry breaking is a core ingredient to achieve electrical manipulation of perpendicular magnetization using spin–orbit torque (SOT) towards ultralow-power, nonvolatile memory, and logic devices1–19. Such SOT-induced magnetization switching mostly exists either in heterostructures consisting of a ferromagnet and a heavy metal with strong SOC (see refs. 3–7,20,21), or in bulk non-centrosymmetric single-layer films such as CuMnAs, Mn2Au, and (Ga,Mn)As with globally or locally broken inversion symmetry8–10. Up to now, remarkable progresses have been made, such as low-power magnetization switching4,5,11, fast domain-wall motion in synthetic antiferromagnetic racetracks14,15, giant spin transfer torque generated by a topological insulator16–18, and so on. However, with the symmetry consideration of many common ferromagnetic films with a centrosymmetric space group, such as Fe, Co, Ni, FeCo, FePt, and CoPt, they themselves cannot have the bulk spin–orbit coupling induced non-equilibrium spin polarization to switch the magnetization22,23, which greatly limit their practical applications in the SOT-based functional devices. Therefore, how to introduce the SOT-switching capability into a common single-layer ferromagnetic film itself is a great challenge.

In order to realize the SOT-switching in the common single-layer ferromagnetic film itself, here, we propose a CoPt composition gradient approach to break the inversion symmetry in otherwise bulk centrosymmetric ferromagnetic alloys. The SOT-switching of the single-layer ferromagnetic film has one obvious advantage that without the need of introducing any extra heavy metal layer to produce SOT effect, the SOT-switching of the single-layer magnetic film can be directly added into the existing devices based on magnetic tunneling junctions, magnetic spin valves, and exchange biased systems to realize a new class of memory and logic functions by SOT effect.

On the other hand, in order to operate nonvolatile memory and logic devices by electrical writing and electrical reading, magnetic field-free SOT induced magnetization switching has been realized by the employment of exchange bias24,25, interlayer exchange coupling26, lateral wedge structures27, ferroelectric control28, geometrical engineering29, and spin current manipulations30–32. However, the switching polarity (clockwise or counterclockwise) of the SOT induced magnetization switching is usually difficult to be reversibly controlled by external manners. Here in order to further realize a controllable field-free SOT-switching, we introduce the CoPt composition gradient film into IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions with the synthetic antiferromagnetic coupling and exchange bias, where the switching polarity can be reversibly controlled by electrical current.

In this work, we not only propose a composition gradient approach to break the inversion symmetry in otherwise bulk centrosymmetric ferromagnetic alloys, which make magnetization switching through bulk spin–orbit coupling possible, but also demonstrate a controllable field-free perpendicular magnetization switching by utilizing the exchange bias and interlayer exchange coupling. As a proof-of-principle experimental example, we demonstrate room temperature SOT switching of the perpendicularly magnetized CoPt alloy single-layer films by introducing an artificial composition gradient in the thickness direction to break the inversion symmetry. It is revealed that the SOT-induced effective field on the domain walls (DWs) leads to the DWs motion and magnetization switching. In addition, field-free perpendicular magnetization switching is obtained in the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions, and its switching polarity can be reversibly controlled. This composition gradient method, which enables the selective and independent control of the magnetization of a single-layer ferromagnetic film, together with controllable field-free SOT switching holds promising applications for electrically controllable magnetic memory and logic devices.

Results

Characterization of the composition gradient CoPt alloy

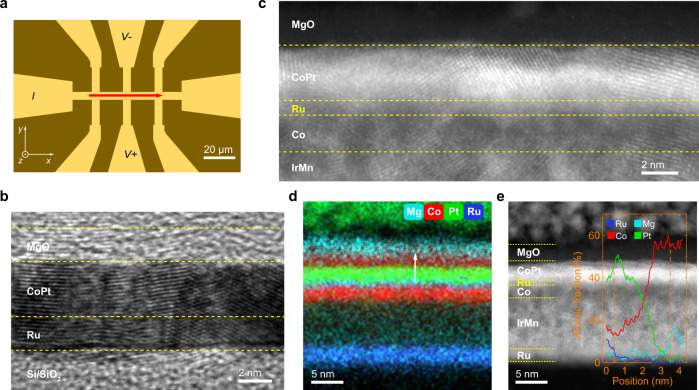

The CoPt ferromagnetic alloy single-layer films with an artificial composition gradient in the thickness direction, which are designed as the nominal multilayered structure of Pt(0.7)/Co(0.3)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.3)/Co(1) (thickness in nanometer), are deposited on Si–SiO2 substrate/Ru buffer layer by using magnetron sputtering at room temperature. Then the deposited films are processed into Hall-bar structures with a 70-μm-long channel along the x-axis and 5-μm in width, as shown in Fig. 1a. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image in Fig. 1b indicates that a high-quality smooth and continuous CoPt alloy film of 3.3 nm in thickness is obtained. The high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) image in Fig. 1c and the HRTEM image in Supplementary Fig. 1 also indicate that CoPt layer in the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt exchange biased sample is a nanocrystal single-layer alloy film, rather than the nominal multilayered structure of Pt(0.7)/Co(0.3)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.3)/Co(1). Moreover, the lattice constant of CoPt(111) is slightly smaller than that of the pure Pt(111) as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, which is consistent with previous reports33.

Microstructure and composition characterization.

a An optical micrograph of the fabricated 70 μm × 5 μm Hall bar. b The high resolution cross-section transmission electron microscopy image of the CoPt alloy single-layer film with the nominal multilayered structure of Pt(0.7)/Co(0.3)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.3)/Co(1), which is grownn on Ru/Si buffer/substrates and capped by MgO protective layer. c the enlarged high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) images, d the elemental mapping, e the HAADF images of the Ru(2)/IrMn(8)/Co(2)/Ru(0.8)/CoPt(3.3)/MgO(2) heterojunction. Inset of e shows the line scanning of the EDS results marked by a white arrow in d. It is clear that the designed nominal multilayered structure of Pt(0.7)/Co(0.3)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.3)/Co(1) has formed the single-layer CoPt alloy with an artificial composition gradient in the thickness direction. In contrast, the Ru(2)/IrMn(8)/Co(2)/Ru(0.8)/CoPt(3.3)/MgO(2) heterojunction still keeps a good multilayered structure.

In order to further confirm the formation of CoPt alloy in our studied systems, we have prepared a control sample of Ru(2)/[Pt(8)/Co(6)]3/Ru(2) with relatively thick Pt and Co layers, and a clear multilayered structure can be observed in the elemental mapping and the HAADF images as shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. However, it is observed that a very thin region about 1.2 nm appears at the Pt/Co interfaces, which has formed the CoPt alloy due to atomic diffusion during the sputtering deposition as confirmed by the line scanning of the energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Supplementary Fig. 3f). Hence, in our studied systems when very thin Pt and Co layers were alternatively sputtered for several times, CoPt alloy single-layer instead of multilayer is synthesized. By contrast, thick Pt and Co layers form Pt/Co multilayers with interfacial alloying.

On the other hand, the elemental mapping of EDS in Fig. 1d and the HAADF image in Fig. 1e reveal that the Ru/IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt/MgO heterojunction still keeps a good multilayered structure due to relatively weak interdiffusion at the interfaces. Despite the interfacial diffusion, Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3c indicate that the thin Ru layer of 0.8 nm is still a separate and continuous sublayer but without sharp interface, which is consistent with the strong antiferromagnetic interlayer exchange coupling in the Ru/IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt/MgO heterojunction.

Now, we focus on the composition gradient of the CoPt alloy layer. The line scanning of EDS results of Ru/IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt/MgO heterojunction is shown in the inset of Fig. 1e. We can see that the Co atomic fraction monotonically increases along the thickness direction from the bottom to the top of the CoPt alloy layer, while the Pt atomic fraction monotonically decreases. It is clear that the composition gradient is along the thickness direction of CoPt alloy layer. However, due to the spread of EDS data, the variation of the composition in our designed samples may be not as continuous as the EDS data, and a more continuous composition gradient can be prepared by continuous deposition.

In the CoPt composition gradient single-layer alloy films, the magnetization versus magnetic field curves (shown in Supplementary Fig. 4a) indicate that the easy magnetization axis of the CoPt films is perpendicular to the film plane. Here, the average saturation magnetization of the 3.3 nm CoPt single-layer films is about 250 emu cm−3 at room temperature. The measured anomalous Hall resistance in Supplementary Fig. 4b, which is proportional to the average vertical component of the CoPt magnetization

Current-induced SOT switching and chiral domain wall movement

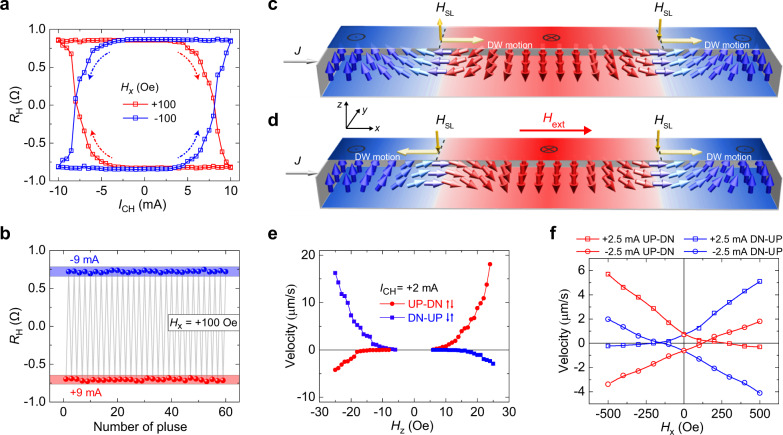

Now we report the reversible electrical current induced magnetization switching for the perpendicularly magnetized CoPt single-layer films. In Fig. 2a, with a small magnetic field along x-axis (

Current-induced magnetization switching and chiral domain wall displacement.

a Current-induced magnetization switching measured under

The current-induced switching loops measured under various

To further clarify the importance of the composition gradient to the SOT-switching, two kinds of control samples are prepared. In the Pt(2)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(2) sample with symmetric structure and no commposition gradient, it is found that although the perpendicular magnetization can be easily switched by the external magnetic field, it cannot be switched by the applied in-plane electrical current due to the symmetric structure, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11. On the other hand, in the Ru(2)/Pt(3.5)/[Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)]8/MgO sample with no composition gradient but still the deposition induced interfacial asymmetry, relatively thick [Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)]8 nominal structure is designed to reveal the possible bulk SOT effect. However, the magnetization switching can not be observed within the maximum applied electrical current density of

When the bulk spin–orbit coupling keeps constant and plays dominant role, in principle there is no limit to the thickness of switchable magnetic films. However, as the Co composition

In order to reveal the mechanism of SOT induced magnetization switching in the CoPt alloy composition gradient films, the magnetic domains were directly observed by magnetic optical Kerr microscope. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15, we can clearly see that the DWs nucleation and propagation dominate the magnetization switching. It is noticed that the critical current of the electrical current line is smaller than that at the junction, which probably due to the current shunting through the arms of the Hall cross24. Therefore, the critical current is defined as the value of

Based on the DWs propagation observed in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15, Fig. 2c, d show the working principle of the SOT switching of perpendicular magnetization in the composition gradient single-layer films. It is believed that the Dzyaloshinskii–Moriya interaction35,41 stabilizes the homochiral Néel DWs (here left-handed Néel DWs with up-to-down and down-to-up configurations) in the CoPt films, as shown in Fig. 2c. For the composition gradient along the thickness direction (z-axis), we can assume that the bulk symmetry-broken is along the z-axis direction, which show the same type of symmetry-broken as interface/surface Rashba effect. Here, the bulk Rashba spin–orbit coupling Hamiltonian of an conducting electron can be described by

It is worthy to mention that the DWs motion depends on the chirality of the DWs, the electrical current, and the magnetic field. From the magnetic domain evolution with time as shown in Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15, we can obtain the domain wall velocity as a function of the applied magnetic field and/or the electrical current, as shown in Fig. 2e, f. Figure 2e shows the experimental results of up-to-down and down-to-up domain wall velocity as a function of out-of-plane magnetic field

Figure 2f shows up-to-down and down-to-up domain wall velocity as a function of in-plane magnetic field

Quantitative evaluation of the SOT effective field

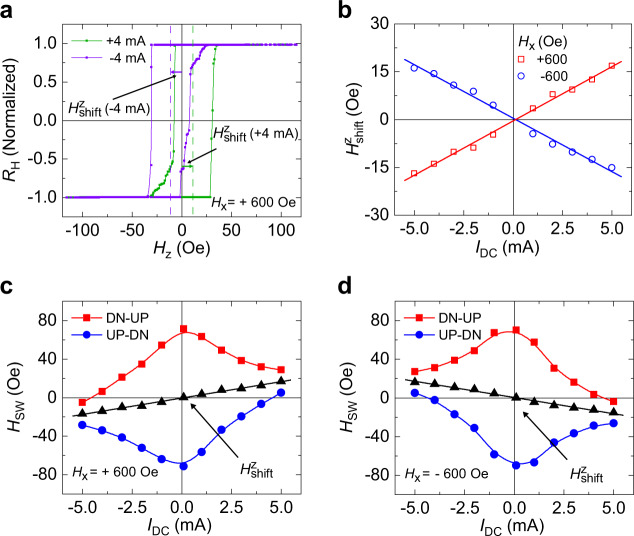

In this section, we quantitatively investigate the SOT effective field which act on the domain walls during the magnetization switching. Figure 3a shows the current induced shift of the out-of-plane hysteresis loops at a fixed bias field

Evaluation of the z component of the spin–orbit effective field on the magnetic Néel DWs.

a The normalized out-of-plane Hall curves measured under a fixed in-plane magnetic field of Hx = +600 Oe and opposite d.c. currents of

We also quantitatively analyze the longitudinal and transverse components of the SOT effective field on single magnetic domains rather than the domain walls by first and second harmonic measurements44,45. By taking into account the contribution from the planar Hall effect as shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, the longitudinal (

With the SOT effective field in mind, we further unveil the mechanism of the electrical current induced magnetization switching. First, it is easy to exclude the Oersted field produced by the electrical current, as it can not explain the observed domain wall motion42. Second, the electrical current induced adiabatic and non-adiabatic spin transfer torques on the domain walls are expected to push the domains to move along the electron drift direction, regardless of the polarity of the domains47. So we can exclude the adiabatic and non-adiabatic spin transfer torques. Third, the spin Hall effect from the nonmagnetic Pt layer can be excluded in our CoPt alloy film, because the spin Hall effect is significant only when the thickness of Pt layer is larger than its spin diffusion length 1.4 nm48, usually in the range of 2–6 nm. In fact, there exists no separate continuous Pt layer in the CoPt alloy film although it is prepared by alternatively sputtering very thin Co and Pt layers. Fourth, the interfacial Rashba effect of the bottom and top interfaces of CoPt alloy film (it indeed exists) is also unlikely to dominate the observed SOT switching, because its interfacial nature usually makes it switch the magnetization of an ultrathin ferromagnetic layer with a thickness around 1.0 nm (see refs. 6,7,49) rather than 3.3 nm in our case. Finally, the composition gradient scenario of the magnetization switching in our CoPt alloy film is further proved by the fact that the polarity of magnetization switching reverses when the composition gradient become opposite, as shown in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10. Combining all the experimental results in Figs. 1–3, we come to the conclusion that CoPt alloy composition gradient produces the bulk symmetry-broken along the z-axis direction, and leads to the bulk Rashba spin–orbit coupling of an conducting electron, which further results in a net current-induced spin–orbit torque to switch the magnetization of the magnetic alloy film50,51. In fact, the composition gradient scenario of the magnetization switching in our CoPt alloy film is well supported by the experimental observation that the Slonczewski-like effective magnetic field

Controllable field-free SOT switching

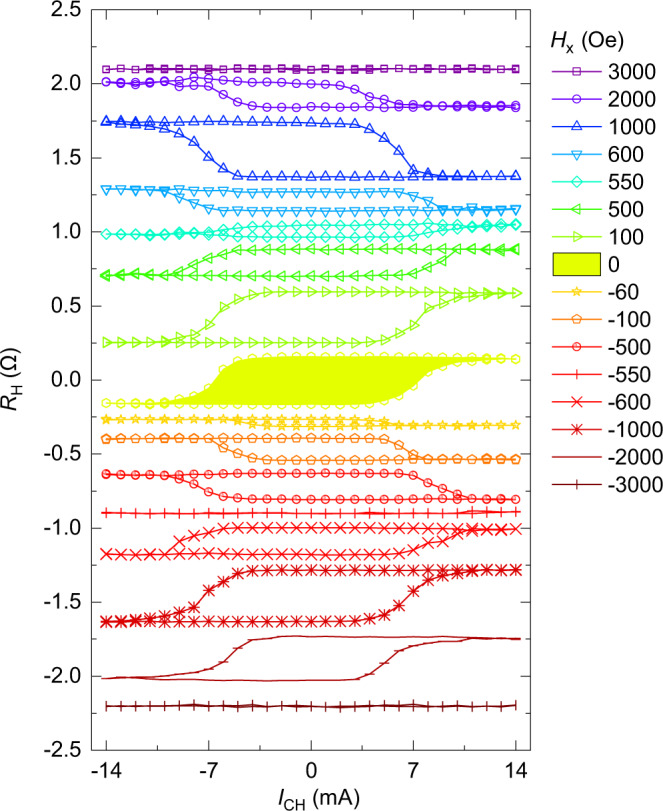

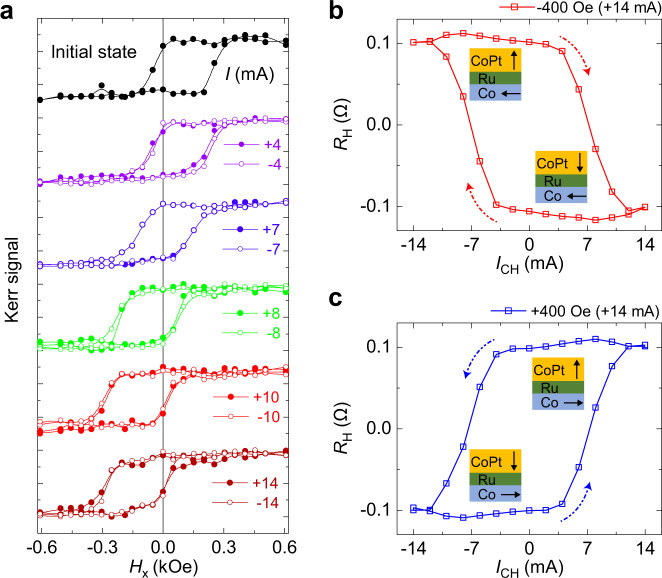

From the application point of view, a controllable field-free SOT switching of perpendicular magnetization is highly desired for a flexible design of functional memory and logic devices. Here, we show that in the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions with the composition gradient CoPt layer, not only the field-free SOT-induced perpendicular magnetization switching, but also its switching polarity of the CoPt alloy layer can be reversibly manipulated by controlling the in-plane exchange bias field between IrMn and Co. In the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions, the top CoPt alloy layer has perpendicular anisotropy, but the bottom Co layer has in-plane anisotropy, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 18. The bottom Co layer and top CoPt alloy layer are antiferromagnetically exchange coupled via a thin Ru spacer of 0.8 nm. In addition, the direct exchange coupling between the bottom Co layer and antiferromagnetic IrMn layer leads to a significant exchange bias field, which is consistent with the shift of in-plane magnetization hysteresis loops (Supplementary Fig. 18). Figure 4 shows the current-induced magnetization switching curves of the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions measured at various

Field-free SOT switching based on exchange bias and interlayer exchange coupling.

The RH–ICH loops measured under various in-plane magnetic fields

Finally, we show how to control the switching polarity of field-free SOT-induced magnetization switching. The initial state is set by applying a positive current pulse of

Controllable switching polarity of the field-free SOT switching.

a In-plane hysteresis loops of the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions measured by magnetic optical Kerr effect. The initial state is set by applying a positive current pulse of

Discussion

Let us compare the main merits of some existing bulk SOT material systems12,19–21,39,56,57, which may be promising for the practical applications in memory and logic devices. First, field-free bulk SOT switching of CoPt composition gradient film is demonstrated in IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions, relying on synthetic antiferromagnetic interlayer coupling through a Ru spacer to an auxiliary Co layer exchange-biased by IrMn. Considering the fact that a remarkable SOT switching in our CoPt films can be observed at the external magnetic field of 100 Oe, the minimum interlayer exchange coupling field should be bigger than 100 Oe to achieve the field-free switching of the maximum magnetic layer thickness. In fact, if we choose a proper Ru layer thickness, we can obtain much big interlayer exchange coupling constant to realize the field-free switching of a relative thick magnetic layer. So this method may be extended to other bulk SOT material systems with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy such as L10 FePt single film12, Co/Pd multilayers20, Co/Pt multilayers19,21,56,57, and CoTb amorphous single layer39 to achieve field-free SOT switching, where previously an external magnetic field is needed to obtain the deterministic magnetization switching. Second, for our 3.3 nm CoPt alloy composition gradient films, the switching critical current density is about

Now let us discuss the relation between the composition gradient and the bulk SOT effect. The composition gradient itself can be greatly modulated by varying the layer thickness and layer number of Co and Pt layers, and correspondingly the SOT effective magnetic field can be effectively tuned as summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Qualitatively speaking, the spin Hall angle, the DMI effective magnetic field, the chirality of the DWs, the damping-like effective magnetic field, and the polarity of magnetization switching all reverses when the composition gradient becomes opposite. But it is hard to quantitatively compare these physical parameters between samples with different composition gradient. For example, the inset of 0.3 nm MgO in the 9.9 nm CoPt film (A4 sample in Supplementary Table 1) simultaneously enhance the coercivity and spin Hall angle as compared with the 3.3 nm CoPt film (A0 sample in Supplementary Table 1), and as a result they have similar critical switching current density. In fact, for most applications in spintronic devices with the magnetic layer thickness usually less than 10 nm, it is easy to prepare the films with various composition gradient and showing efficient current-induced magnetization switching. Up to now, although the bulk spin–orbit torque has been found in a few magnetic single-layer films and multilayers12,19–21,39,56,57, the mechanisms of structure/crystal inversion asymmetry are still controversial. However, rigorous theoretical calculations may be a good alternative approach to further verify the origin of bulk spin–orbit torque, and systematic experimental studies are required to obtain a quantitative relation between the SOT strength and the composition gradient, which is beyond the scope of this work.

In summary, within this study we have demonstrated the SOT switching of the perpendicularly magnetized CoPt single-layer ferromagnetic films by introducing the artificial composition gradient in the thickness direction to break the inversion symmetry. Moreover, a controllable field-free spin–orbit torque switching of the CoPt layer is obtained relying on the synthetic antiferromagnetic coupling and exchange bias in IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions. Our findings may advance the practical applications of SOT systems in energy efficient memory and logic devices, since this simple composition gradient approach enables the selective electrical control of the magnetization switching of a single-layer ferromagnetic film.

Methods

Growth of composition gradient CoPt alloys

The CoPt composition gradient alloys with the nominal multilayered structure of Pt(0.7)/Co(0.3)/Pt(0.5)/Co(0.5)/Pt(0.3)/Co(1) (thickness in nanometers) were deposited on a thermally oxidized Si (001) substrates coated with 300 nm thick SiO2. A 2 nm Ru buffer layer with a weak spin–orbit coupling is used to avoid strong spin Hall effect of heavy metal while improving the crystal quality, and a 2 nm MgO capping layer was grown to protect the films from being oxidized by the atmosphere. On the other hand, during the sputtering of MgO layer, partial oxygen atoms can diffuse into CoPt layer from the interface, which will further form the composition gradient of O atoms in the CoPt alloy and weaken the magnetization of CoPt alloy film. The Ru, Pt, and Co metal layers were deposited by d.c. magnetron sputtering at 3 mTorr Ar, and MgO was radiofrequency (RF) sputtered at 6 mTorr. The base pressure was better than

Growth of IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions

The IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions with the composition gradient CoPt alloy layer were prepared by sputtering, and have the thicknesses of Ru(2)/IrMn(8)/Co(2)/Ru(0.8)/CoPt(3.3), which were protected by 2 nm MgO as a cap layer. Then the heterojunctions were annealed at 300 °C under an in-plane magnetic field of 4000 Oe to promote the exchange bias between IrMn and Co.

Microstructure and composition characterization

The high resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) analysis, the high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) imaging, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) elemental analysis were performed with a FEI Titan Themis 60-300 microscope equipped with a probe spherical aberration (Cs) corrector operated at 300 kV. The EDS system is equipped with super-X detector and its energy resolution is 137 meV. The EDS line scanning and mapping results were performed under scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mode.

Magnetic optical Kerr effect (MOKE) measurements

Magnetic domain images were observed by MOKE microscopy of an EVICO system. Both the time and the position of magnetic domain walls were extracted from the MOKE images. And the domain wall velocity was then calculated by using MOKE images over a certain time interval. The longitudinal Kerr signal of the IrMn/Co/Ru/CoPt heterojunctions shown in Fig. 5 was measured after the set/reset magnetic field and current pulses were removed.

Magnetic and electrical properties measurements

The magnetic hysteresis loops were measured using superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID, Quantum Design, MPMS-XL 7) and the typical sample size was 5 mm × 5 mm. For the electrical transport measurements, the films were patterned into conventional Hall bar structure with a channel width of 5 μm and length of 70 μm by using optical lithography and Ar-ion beam etching. Four-points Hall measurements were conducted using the Oxford physical property measurement system. The anomalous Hall resistance

Perpendicular effective field acting on the DWs

The out-of-plane anomalous Hall curves under different d.c. currents were measured by using Keithley 6221 and Keithley 2182A, while an in-plane bias magnetic field was applied along the current flow direction. Then we extracted the switching fields (

First and second harmonic measurements

The current-induced effective fields on the magnetic domains were measured using a low-current excitation lock-in technique. A constant sinusoidal a.c. current

The planar Hall effect (PHE) was measured by applying a 5 T in-plane magnetic field and rotating the sample around the vertical axis. Then the effective field-like or damping-like field are corrected according to the following equation:

Here, the

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22819-4.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11774199, 11774016, and 51871112), the 111 Project B13029. The authors thank P. Shi and Q. K. Huang for their experimental support.

Author contributions

Y.F.T. and S.S.Y. conceived and designed the experiments. Y.N.D., X.X.J., and X.H. fabricated the samples. X.L.Q., K.Z., and X.D.H. performed the TEM and EDS measurements. X.X.J., X.N.Z., and Y.B.F. performed the electrical and magnetic measurements. L.H.B., Y.X.C., and Y.Y.D. contribute to the data analysis. X.X.J., X.N.Z., Y.F.T., and S.S.Y. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results, contributed to the data analysis and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figs. 1–19 and Supplementary Table 1). Extra data are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

Controllable field-free switching of perpendicular magnetization through bulk spin-orbit torque in symmetry-broken ferromagnetic films

Controllable field-free switching of perpendicular magnetization through bulk spin-orbit torque in symmetry-broken ferromagnetic films