- Altmetric

The Higgs mechanism, i.e., spontaneous symmetry breaking of the quantum vacuum, is a cross-disciplinary principle, universal for understanding dark energy, antimatter and quantum materials, from superconductivity to magnetism. Unlike one-band superconductors (SCs), a conceptually distinct Higgs amplitude mode can arise in multi-band, unconventional superconductors via strong interband Coulomb interaction, but is yet to be accessed. Here we discover such hybrid Higgs mode and demonstrate its quantum control by light in iron-based high-temperature SCs. Using terahertz (THz) two-pulse coherent spectroscopy, we observe a tunable amplitude mode coherent oscillation of the complex order parameter from coupled lower and upper bands. The nonlinear dependence of the hybrid Higgs mode on the THz driving fields is distinct from any known SC results: we observe a large reversible modulation of resonance strength, yet with a persisting mode frequency. Together with quantum kinetic modeling of a hybrid Higgs mechanism, distinct from charge-density fluctuations and without invoking phonons or disorder, our result provides compelling evidence for a light-controlled coupling between the electron and hole amplitude modes assisted by strong interband quantum entanglement. Such light-control of Higgs hybridization can be extended to probe many-body entanglement and hidden symmetries in other complex systems.

A collective excitation called Higgs mode may arise in multi-band superconductors via strong interband interaction, but it is yet to be accessed. Here, the authors observe a tunable coherent amplitude oscillation of the order parameter in Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2, suggesting appearance and control of the Higgs mode by light tuning interband interaction.

Introduction

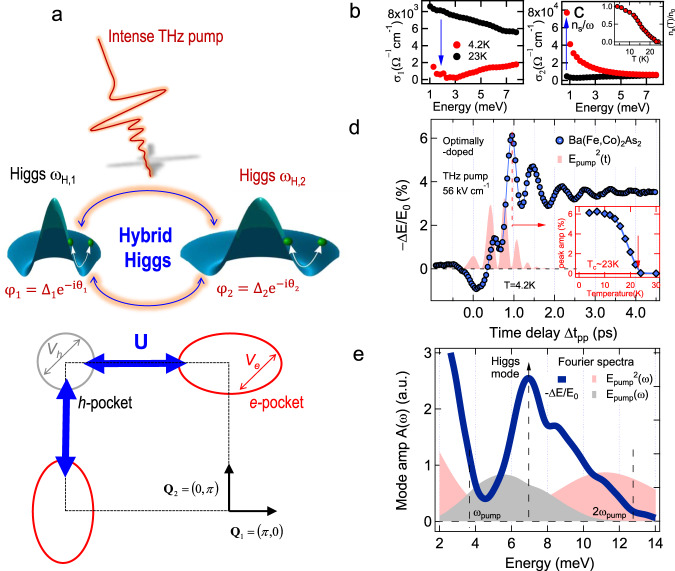

Amplitude modes and their competition with charge-density fluctuations are currently intensely studied in one-band superconductors (SCs). In multi-band, unconventional SCs, a hybrid Higgs amplitude mode, controllable by terahertz (THz) laser pulses, can arise via strong interband Coulomb interaction. A recent prominent example to explore such collective mode is seen in iron-arsenide based superconductors (FeSCs). Phase coherence between multiple SC condensates in different strongly interacting bands is well established in FeSCs. As illustrated in Fig. 1a, a dominant Coulomb coupling between the h- and e-like Fermi sea pockets, unlike in other SCs, is manifested by, e.g., s± pairing symmetry1,2, spin-density wave resonant peaks, and nesting wave vectors (black arrows)3–6. Despite the extensive studies, experimental evidence for Higgs amplitude coherent excitations in FeSCs has not been reported yet, despite recent progress in non-equilibrium superconductivity and collective modes7–22.

The 2ΔSC coherent oscillations detected by two-pulse THz coherent spectroscopy of multi-band FeSCs.

a Illustration of coherent excitation of hybrid Higgs mode via THz quantum quench. An effective three-band model has a h pocket at the Γ point and two e pockets at X/Y points, with strong inter- (blue) and weak intraband (gray and red) interactions marked by arrows. b, c Real and imaginary parts of the complex THz conductivity spectra σ1(ω) and σ2(ω) in the superconducting (4.2 K) and normal states (23 K) of Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2 (x = 0.08) in equilibrium. Inset of c shows the temperature dependence of the superfluid density normalized to its value at 4.2 K, ns(T)/n0, as determined from 1/ω divergence of σ2(ω) (blue arrow in c). d Differential THz transmission ΔE/E0 (blue circles) measured by phase-locked two-THz-pulse pump–probe spectroscopy at 4.2 K shows pronounced coherent oscillations for a peak THz field strength of Epump = 56 kV/cm. The pink shaded curve denotes the square of the pump THz waveform . Inset: Temperature dependence of the peak amplitude of ΔE/E0. e Fourier spectrum of the coherent oscillations in ΔE/E0 (blue line) exhibits a resonance peak at ~6.9 meV (blue line) and is distinct from both the pump Epump (gray) and pump-squared

The condensates in different bands of Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2 studied here, shown in Fig. 1a, are coupled by the strong interband e–h interaction U (blue double arrow vector), which is about one order of magnitude stronger than the intraband interaction V (gray and red double arrows)23. For U ≫ V, the formation channels of collective modes are distinct from one-band SC7–9,24 and multi-band MgB2 with dominant intraband interaction, V ≫ U25,26. For the latter, only Leggett modes are observed thus far10. In contrast, for U ≫ V, one expects Higgs amplitude modes arising from the condensates in all Coulomb-coupled bands, i.e., in the h pocket at the Γ-point (gray circle, mode frequency ωH,1), and in the two e pockets at (0, π) and (π, 0) (red ellipses, ωH,2). A single-cycle THz oscillating field (red pulse) can act like a quantum quench, with impulsive non-adiabatic driving of the Mexican-hat-like quantum fields (dark green) and, yet, with minimum heating of other degrees of freedoms. Consequently, the multi-band condensates are forced out of the free energy minima, since they cannot follow the quench adiabatically. Most intriguingly, such coherent nonlinear driving not only excites amplitude mode oscillations in the different Fermi sea pockets, but also transiently modifies their coupling, assisted by the strong interband interaction U. Such coherent transient coupling can be regarded as nonlinear amplitude mode hybridization with a time-dependent phase coherence. In this way, THz laser fields can manipulate hybrid Higgs emerging collective modes in FeSCs, assisted by the strong interband interaction.

Here we present evidence of hybrid Higgs modes that are excited and controlled by THz-field-driven interband quantum entanglement in a multi-band SC, optimally doped Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2, using two phase-locked near-single-cycle THz laser fields. We reveal a striking nonlinear THz field dependence of coherent amplitude mode oscillations: quick increase to maximum spectral weight (SW) with negligible mode frequency shift, followed by a huge SW reduction by more than 50%, yet with robust mode frequency position, with less than 10% redshift. These distinguishing features of the observed collective mode are different from any one-band and conventional SC results and predictions so far. Instead, they are consistent with coherent coupling between the e- and h-like amplitude modes . To support this scenario, we perform quantum kinetic modeling of a hybrid Higgs mechanism without invoking extra disorder or phonons. This simulation identifies the key role of the interband interaction U for coherently coupling two amplitude modes and for controlling the SW of the lower Higgs mode observed in the experiment.

Results

The amplitude coherent oscillations detected by THz two-pulse coherent spectroscopy

The equilibrium complex conductivity spectra, i.e., real and imaginary parts, σ1(ω) and σ2(ω), of our epitaxial Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2 (x = 0.08) film27 (Methods) measure the low-frequency quasi-particle (QP) electrodynamics and condensate coherence, respectively (Fig. 1b, c)28. The normal state (black circles) displays Drude-like behavior, while the QP spectral weight in σ1(ω) is depleted in the SC state due to SC gap openings, seen, e.g., in the 4.2 K trace (red circles). The lowest SC gap value 2Δ1 ~ 6.8 meV obtained is in agreement with the literature values 6.2–7 meV29,30 (Methods). Such σ1(ω) spectral weight depletion is accompanied by an increase of condensate fraction ns/n0 (inset, Fig. 1c), extracted from a diverging 1/ω condensate inductive response, marked by blue arrow, e.g., in the 4.2 K lineshape of σ2(ω) (Fig. 1c). Note that the superfluid density ns vanishes above Tc ~ 23 K (inset Fig. 1c).

We characterize the THz quantum quench coherent dynamics directly in the time domain31–33 (Methods) by measuring the responses to two phase-locked THz pulses as differential field transmission of the weak THz probe field ΔE/E0 (blue circles, Fig. 1d) for THz pump field, Epump = 56 kV/cm and as a function of pump–probe time delay Δtpp. The central pump energy ℏωpump = 5.4 meV (gray shade, Fig. 1e) is chosen slightly below the 2Δ1 gap. Intriguingly, the ΔE/E0 dynamics reveals a pronounced coherent oscillation, superimposed on the overall amplitude change, which persists much longer than the THz photoexcitation (pink shade). This mode is excited by the quadratic coupling of the pump vector potential,

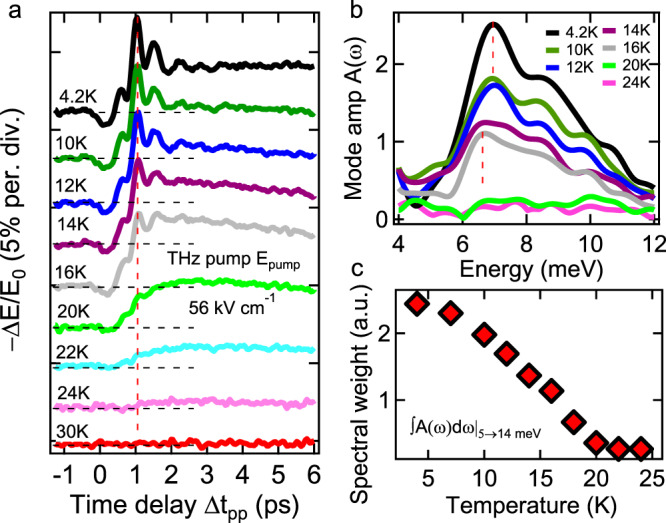

Figure 2 reveals a strong temperature dependence of the Higgs mode oscillations. The coherent dynamics of ΔE/E0 is shown in Fig. 2a for temperatures 4.2–30 K. Approaching Tc from below, the coherent oscillations quickly diminish, as seen by comparing the 4.2 K (black line) and 16 K (gray) traces versus 22 K (cyan) and 24 K (pink) traces. Figure 2b shows the temperature-dependent Fourier spectra of ΔE/E0, in the range 4–12 meV. Figure 2c plots the integrated spectral weight SW5→14meV of the amplitude mode (Fig. 2b). The strong temperature dependence correlates the mode with SC coherence. Importantly, while the mode frequency is only slightly red-shifted, by less than 10% before full SW depletion close to Tc, SW is strongly suppressed, by ~55% at 16 K (T/Tc ~ 0.7). Such a spectral weight reduction in FeSCs is much larger than expected in one-band BCS superconductors or for U = 0 shown later. We also note that the temperature dependence of Higgs oscillations, observed in FeSCs here, has not been measured experimentally in conventional BCS systems, and could represent a key signature of quantum quench dynamics of unconventional SCs. The observed behavior is consistent with our simulations of the hybrid Higgs mode in multi-band SCs with dominant interband U, shown later.

Temperature dependence of hybrid Higgs mode coherent oscillations in FeSCs.

a Temporal profiles of −ΔE/E0 at various temperatures and for a peak THz pump E-field of Epump = 56 kV/cm. Traces are offset for clarity. b Fourier spectra of the Higgs mode oscillations derived from the two-pulse coherent pump–probe signals at different temperatures. Dashed red lines indicate the slight redshift of the Higgs mode frequency with the drastic reduction of mode SW as a function of temperature. c Temperature dependence of the integrated SW5→14meV of the Higgs mode in b.

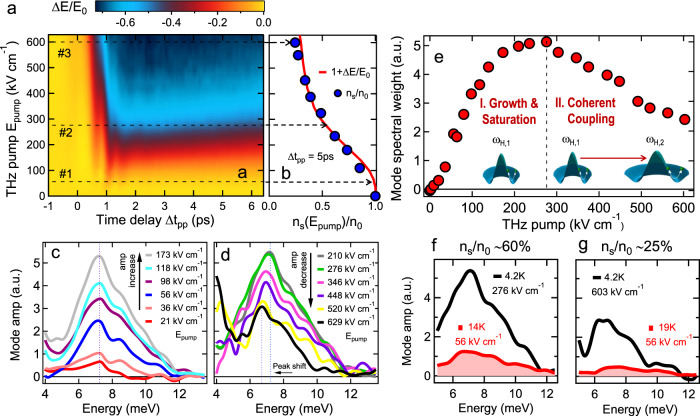

Nonlinear THz field dependence of hybrid Higgs mode in FeSCs

Figure 3 presents distinguishing experimental evidence for the hybrid Higgs mode in FeSCs, which is different from one-band SCs – a highly nonlinear THz electric field dependence of coherent 2Δ1 oscillations that manifests as a huge SW change, yet with persisting mode frequency, i.e., with only very small redshift. Figure 3a shows the detailed pump-fluence dependence of ΔE/E0 as a function of time delay, presented as a false-color plot at T = 4.2 K for up to Epump ~ 600 kV/cm. It is clearly seen that amplitude mode oscillations depend nonlinearly on the Epump field strength. 1 + ΔE/E0 (red solid line) at Δtpp = 5 ps is shown in Fig. 3b. This, together with the measured ~1/ω divergence in σ2(ω, Δtpp), allows the determination of the condensate fraction ns(Epump)/n0 (blue circles) in the driven state (Supplementary Fig. 6). There shows three different excitation regimes, marked by black dash lines in Fig. 3a–b: (1) in regime #1, the condensate quench is minimal, e.g., ns/n0 ≥ 97% below the field E#1 = 56 kV/cm; (2) Regime #2 displays partial SC quench, where ns/n0 is still significant, e.g., condensate fraction ≈60% at E#2 = 276 kV/cm; (3) A saturation regime #3 is observed ~E#3 = 600 kV/cm, which leads to a slowly changing ns/n0 approaching a saturation ~25%. The saturation is expected since below gap THz pump is used, especially ℏωpump ≪ 2Δ2 ~ 15–19 meV at the e-like pockets29,30.

Nonlinear THz field dependence of hybrid Higgs mode in FeSCs.

a A 2D false-color plot of ΔE/E0 as a function of pump E-field strength Epump and pump–probe delay Δtpp at 4.2 K. b THz pump E-field Epump dependence of 1 + ΔE/E0 (red line) overlaid with the superfluid density fraction ns/n0 (blue circles) after THz pump at Δtpp = 5 ps and T = 4.2 K. Dashed arrows (black) mark the three pump E-field regimes, i.e., weak, partial, and saturation, identified in the main text. c, d Spectra of coherent Higgs mode oscillations show a distinct non-monotonic dependence as a function of THz pump field, i.e., a rapid increase in the mode amplitude for low pump E-field strengths up to 173 kV/cm, saturation up to 276 kV/cm and significant reduction at higher fields. The blue dashed line marks the resonance of the mode and the redshift of the Higgs mode peak, much smaller than the mode SW change. e Integrated spectral weight SW5→14meV of the Higgs mode at various pump E-field strengths, indicating the SW reduction of the Higgs mode from dominant ωH,1 at low driving fields to ωH,2 due to the interband interaction and coherent coupling, illustrated in the inset, at high driving fields above Epump = 276 kV/cm. f, g Contrasting the thermal and THz-driven states of coherent hybrid Higgs mode spectral weight by comparing the mode spectra at the similar superfluid density f ns/n0 = 60% and g ns/n0 = 25% achieved by THz pump (black solid lines) and temperature (red shades).

Quantum quenching of the single-band BCS pairing interaction has been well established to induce Higgs oscillations with amplitude scaling as 1/

The distinct mode amplitude and position variation with pump field extracted from the coherent oscillations clearly show the transition from SW growth and saturation to reduction, marked by the black dashed line at Epump = 276 kV/cm (Fig. 3e). The saturation and reduction of SW in the amplitude oscillation, yet with a persisting mode frequency, cannot be explained by any known mechanism. This can arise from the coupling of the two amplitude modes ωH,1 and ωH,2 expected in iron pnictides due to the strong inter-pocket interaction U. The coherent coupling process can be controlled and detected nonlinearly by THz two-pulse coherent spectroscopy, as clearly shown in Fig. 3e. We argue that (I) At low driving fields, ωH,1 dominates the hybrid collective mode due to less damping than ωH,2 arising from the asymmetry between the electron and hole pockets; (II) For higher fields, SW of ωH,1 mode decreases due to the coherent transfer to ωH,2 mode expected for the strong interband interaction in iron pnictides. Moreover, it is critical to note that the THz driving is of highly nonthermal nature, which is distinctly different from that obtained by temperature tuning in Fig. 2. Specifically, Fig. 3f, g compare the hybrid Higgs mode spectra for similar condensate faction ns/n0, i.e., ≈60% (f) and 25% (g), induced by tuning either the temperature (red shade) or THz pump (black line). The mode amplitude is clearly much stronger in the THz-driven coherent states than in the temperature tuned ones.

Quantum kinetic calculation of the THz-driven hybrid Higgs dynamics

To put the above hybrid Higgs mode findings on a rigorous footing, we calculate the THz coherent nonlinear spectra (Methods) by extending the gauge-invariant density matrix equations of motion theory of ref. 38, as outlined in the Supplementary Note 6. Using the results of these calculations, we propose a physical mechanism that explains the distinct differences of the Higgs mode resonance in the four-wave mixing spectra between the strong and weak interband interaction limits. For this, we calculate the APS and quantum transport nonlinearities38 driven by two intense phase-locked THz E-field pulses for an effective 3-pocket BCS model of FeSCs39. This model includes both intraband and interband pairing interactions, as well as asymmetry between electron and hole pockets. We thus calculate the nonlinear differential field transmission ΔE/E0 for two phase-locked THz pulses, which allows for a direct comparison of our theory with the experiment (Supplementary Note 6).

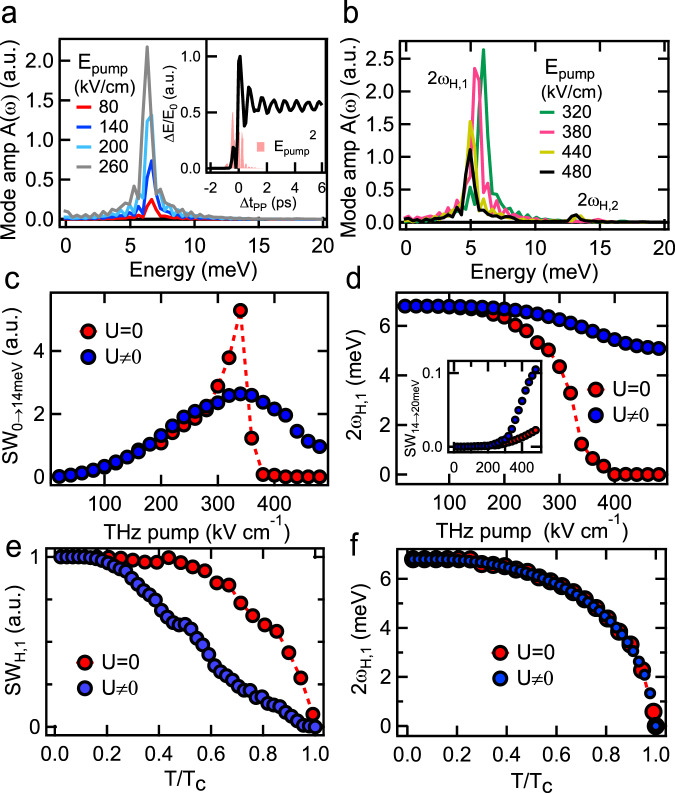

The inset of Fig. 4a presents the calculated ΔE/E0 (black line), shown together with

Gauge-invariant quantum kinetic calculation of the THz-driven hybrid Higgs dynamics.

a Calculated Higgs mode spectra for low pump E-field strengths. Inset: Calculated ΔE/E0 for peak Epump = 380 kV/cm (black) and its comparison with the waveform

To scrutinize further the critical role of the strong interband interaction U, we show the fluence dependence of the coherent Higgs SW close to ωH,1 in Fig. 4c. SW0→14meV differs markedly between the calculation with strong U ≠ 0 (blue circles) and that without inter-pocket interaction U = 0 (red circles), which resembles the one-band BCS quench results. Importantly, the Higgs mode SW0→14meV for strong U grows at low pump fluences (regime I), followed by a saturation and then decrease at elevated Epump (regime II), consistent with the experiment. Meanwhile, Fig. 4d demonstrates that the resonance frequency remains constant in regime I, despite the strong increase of SW, and then redshifts in regime II, yet by much less than in the one-band system (compare U ≠ 0 (blue circles) vs. U = 0 (red circles)). Without inter-pocket U (U = 0, red circles in Fig. 4c–d), the SW of Higgs mode ωH,1 grows monotonically up to a quench of roughly 90%. A further increase of the pump field leads to a complete quench of the order parameter Δ1 and a decrease of the SW of Higgs mode ωH,1 to zero, due to transition from a damped oscillating Higgs phase to an exponential decay. Based on the calculations in Fig. 4c–d, the decrease of the spectral weight with interband coupling appears at a Δ1 quench close to 15%, while without interband coupling the decrease of spectral weight is only observable close to the complete quench (~90%) of the SC order parameter Δ1. We conclude from this that the spectral weight decrease at the lower Higgs resonance with low redshift is a direct consequence of the strong coupling between the electron and hole pockets due to large U. This Epump dependence is the hallmark signature of the Higgs mode in FeSCs and is fully consistent with the Higgs mode behaviors observed experimentally.

Finally, the temperature dependence of the hybrid Higgs mode predicted by our model is shown in Fig. 4e, f for U = 0 (red circles) and U ≠ 0 (blue circles). With interband coupling, the SW is strongly suppressed, by about 60% up to a temperature of 0.6Tc, while at the same time the mode frequency is only slightly redshifted, by about 15%, before a full spectral weight depletion is observable towards Tc. The strong suppression results from transfer of SW from mode ωH,1 to the higher mode ωH,2 with increasing temperature, since the higher SC gap Δ2 experiences stronger excitation by the applied pump E2 with growing T. These simulations are in agreement with the hybrid Higgs behavior in Fig. 2 and differ from one-band superconductors showing comparable change of both SW and position of the Higgs mode with increasing temperature (red circles, Fig. 4e, f). Moreover, our calculation without light-induced changes in the collective effects (only charge-density fluctuations) produces a significantly smaller ΔE/E0 signal in the non-perturbative excitation regime (Supplementary Fig. 11). Therefore, we conclude that the hybrid Higgs mode dominates over charge-density fluctuations in two-pulse coherent nonlinear signals in FeSCs, due to the different effects of the strong interband U and multi-pocket bandstructure on QPs and on Higgs collective modes.

In summary, we provide distinguishing features for hybrid Higgs modes and thier coherent excitations in multi-band FeSCs, which differ significantly from any previously observed collective mode in other superconducting materials: 2ΔSC amplitude oscillations displaying a robust mode resonance frequency position despite a large change of its spectral weight, more than 50%, on the THz electric field. This unusual nonlinear quantum behavior provides evidence for Higgs hybridization from the interband quantum entanglement in FeSCs. Such discovery and light-control of the hybrid Higgs mode in multi-band unconventional SCs inspire future research of quantum tomography of many-body correlated states in complex systems.

Methods

Sample preparation

We measure optimally Co-doped BaFe2As2 epitaxial single-crystal thin films27 which are discussed in Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2. They are 60 nm thick, grown on 40 nm thick SrTiO3 buffered (001)-oriented (La;Sr)(Al;Ta)O3 (LSAT) single-crystal substrates. The sample exhibits a SC transition at Tc ~ 23 K (Supplementary Fig. 2). The base pressure is below 3 × 10−5 Pa and the films were synthesized by pulsed laser deposition with a KrF (248 nm) ultraviolet excimer laser in a vacuum of 3 × 10−4 Pa at 730∘C (growth rate: 2.4 nm/sec). The Co-doped Ba-122 target was prepared by solid-state reaction with a nominal composition of Ba/Fe/Co/As = 1:1.84:0.16:2.2. The chemical composition of the thin film is found to be Ba(Fe0.92,Co0.08)2As1.8, which is close to the stoichiometry of Ba122 with 8% (atomic %) optimal Co-doping. The PLD targets were made in the same way using the same nominal composition of Ba(Fe0.92,Co0.08)2As2.2 (Supplementary Note 1). The epitaxial and crystalline quality of the optimally doped BaFe2As2 thin films was measured by four-circle X-ray diffraction (XRD) shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 for the out-of-plane θ–2θ scans of the films. As an example, the full width half maximum (FWHM) of the (004) reflection rocking curve of the films is as narrow as 0.7∘, which indicates high-quality epitaxial thin films. Furthermore, we have also performed chemical, structural, and electrical characterizations of epitaxial Co-doped BaFe2As2 (Ba-122) superconducting thin films. We determined the chemical composition of Ba122 thin films by wavelength dispersive spectroscopy (WDS) analyses. The chemical composition of the thin film is found to be Ba(Fe0.92,Co0.08)2As1.8, which is close to the stoichiometry of Ba122 with 8% (atomic %) optimal Co-doping. We measured temperature-dependent electrical resistivity for superconducting transitions by four-point method (Supplementary Fig. 2). Onset Tc and Tc at zero resistivity are as high as 23.4 and 22.0 K, respectively, and ΔTc is as narrow as 1.4 K, which are the highest and narrowest values for Ba-122 thin films. In our prior papers, one can also check a zero-field-cooled magnetization Tc and it clearly shows a diamagnetic signal by superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer measurements.

Properties of the thin film Co-doped BaFe2As2 samples used

The lowest SC gap values 2Δ1 ~ 6.8 meV were obtained in our THz conductivity data using a Mattis-Bardeen approach similar to that used in28–30. Specifically, Supplementary Fig. 7 plots together the THz conductivity of our single-crystal film sample and prior FTIR conductivity of single-crystal samples at the similar doping29. They show an excellent agreement which indicate similar superconducting energy gaps of both samples. The two superconducting energy gaps obtained from the FTIR data are 2Δ1 ~ 6.2 meV that agrees with our 2Δ1 value, and 2Δ2 ~ 14.8–19 meV29,30. The further analysis of THz conductivity spectra of our sample also allows the determination of other key equilibrium electrodynamics and transport parameters, consistent with the prior literature3,6. First, we can obtain the plasma frequency ωp, obtained by fitting the normal state conductivity spectra with the Drude model, which gives the plasma frequency to be ~194 THz (~804 meV) and the scattering rate ~2.5 THz (~10 meV). These measurements are in excellent agreement with bulk single-crystal samples at optimal doping29: a normal state Drude plasma frequency of 972 meV, scattering rate 15 meV was obtained there. Second, the London penetration depth λL = 378 nm, corresponding to a condensed fraction of ~50%. These are again consistent with the prior measurements of high quality bulk samples, which show ~50% of the free carriers participating in superfluidity below Tc and a penetration depth of 300 nm.

Two-pulse THz coherent nonlinear spectroscopy

Our THz pump–THz probe setup, illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4, can be understood within the general framework of THz 2D spectroscopy. The experiment is driven by a 1 kHz fs laser amplifier40 and performed in the collinear geometry with two pulses EA and EB with wave vectors

Time-resolved complex THz conductivity spectra

Unlike for the Fourier spectra of coherent FWM signals of main interest here, THz PP signals (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Eq. (1), Supplementary Note 2) directly access the time-dependent complex conductivity spectra, i.e., real and imaginary parts, σ1(ω, ΔtPP), σ2(ω, ΔtPP), shown in Supplementary Fig. 5 for a fixed time delay ΔtPP = 5 ps. PP signal measurements extend the conventional, equilibrium complex conductivity σ1(ω) and σ2(ω) measurement (black and gray circles, Supplementary Fig. 5) to characterize the non-equilibrium post-THz-quench superconducting states. σ1(ω, ΔtPP), σ2(ω, ΔtPP) are shown for E-field = 44 kV/cm (red circles) and E-field = 88 kV/cm (blue circles) in Supplementary Fig. 5. The static conductivity can be fitted with Drude-like behavior of quasi-particles in the normal state (black circles) and condensate gaps of 2Δ = 6.8 meV in the SC state (red circles) (discussed later in Supplementary Fig. 7). The PP conductivity spectra identify the minimal quenching of condensate density of few percent for tens of kV/cm E-field used in observing coherent oscillations. Time-dependence of superfluid density can be directly obtained by the diverging σ2(ω, ΔtPP) ∝ ns/ω in Supplementary Fig. 5. Furthermore, we also plot Supplementary Fig. 6a from three representative line-cuts in Fig. 3a (main text) and then compare this with the condensate fraction (Supplementary Fig. 6b) extracted from the usual diverging response in σ2(ω) (Supplementary Fig. 6c). It is clear that, after the oscillation, ΔE/E0 closely follows the pump-induced change in condensate density, Δns/n0. For example, for weak THz excitation Epump = 56 kV/cm and below Tc, the THz pump pulse only reduces ns slightly, e.g., ΔE/E0 ∝ Δns/n0 ~ −3%.

Gauge-invariant theory and simulations of THz coherent nonlinear spectroscopy in FeSCs

We start from the microscopic spatial-dependent Boguliobov–de Gennes Hamiltonian for multi-band superconductors

Here the Fermionic field operators

The SC complex order parameter components arising from the condensates in the different Fermi sea pockets are

Hamiltonian (1) is gauge-invariant under the gauge transformation

The equation of motion for

In our calculations we solve the gauge-invariant optical Bloch equations (9) for a 3-pocket model with a hole (h) pocket centered at the Γ-point and two electron (e) pockets located at (π, 0) and (0, π). We include the inter e–h pocket interactions (U = ge,h = gh,e) as well as intra-pocket interactions (Vλ = gλ,λ) while inter e–e pocket interactions are neglected for simplicity. The dominance of interband coupling U between e–h pockets over intraband in Fe-based SCs is taken into account by using an interband-to-intraband interaction ratio of r = U/V = 10. The pockets are modeled using the square lattice nearest-neighbor tight-binding dispersion

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20350-6.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Science Foundation 1905981 (THz spectroscopy and data analysis). The work at UW-Madison (synthesis and characterizations of epitaxial thin films) was supported by the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES), under award number DE-FG02-06ER46327. Theory work at the University of Alabama, Birmingham was supported by the US Department of Energy under contract # DE-SC0019137 (M.M and I.E.P) and was made possible in part by a grant for high performance computing resources and technical support from the Alabama Supercomputer Authority (quantum kinetic calculations). L.L. was supported by the Ames Laboratory, the US Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science and Engineering Division under contract No. DEAC0207CH11358 (technical assistance).

Author contributions

C.V., L.L., and X.Y. performed the THz spectroscopy measurements with J.W.’s supervision. J.H.K, C.S., and C.B.E. grew the samples and performed structural characterizations and transport measurements. M.M. and I.E.P. developed the theory for the hybrid Higgs mode and performed calculations. Y.G.C and E.E.H made Ba122 target for epitaxial thin films. J.W. and C.V. analyzed the THz data with the help of L.L., D.C., C.H., R.J.H.K., and Z.L. The paper is written by J.W., M.M., and I.E.P. with discussions from all authors. J.W. conceived and supervised the project.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

Light quantum control of persisting Higgs modes in iron-based superconductors

Light quantum control of persisting Higgs modes in iron-based superconductors