The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

In tumor metastasis, the margination and adhesion of tumor cells are two critical and closely related steps, which may determine the destination where the tumor cells extravasate to. We performed a direct three-dimensional simulation on the behaviors of the tumor cells in a real microvascular network, by a hybrid method of the smoothed dissipative particle dynamics and immersed boundary method (SDPD-IBM). The tumor cells are found to adhere at the microvascular bifurcations more frequently, and there is a positive correlation between the adhesion of the tumor cells and the wall-directed force from the surrounding red blood cells (RBCs). The larger the wall-directed force is, the closer the tumor cells are marginated towards the wall, and the higher the probability of adhesion behavior happen is. A relatively low or high hematocrit can help to prevent the adhesion of tumor cells, and similarly, increasing the shear rate of blood flow can serve the same purpose. These results suggest that the tumor cells may be more likely to extravasate at the microvascular bifurcations if the blood flow is slow and the hematocrit is moderate.

Cancer is one of leading causes of death in the world, but unfortunately, the mechanism of tumor metastasis remains unclear so far. Intuitively, the tumor metastasis starts from a tumor cell migrating towards the vessel wall (namely margination), then adhering to the vessel wall (namely adhesion), and finally extravasating from where it adheres onto. Hence, it is important to investigate the margination and adhesion of tumor cells for understanding the tumor metastasis. We implemented a three-dimensional simulation to directly reproduce these two processes at a cellular scale, where the dynamic behaviors, such as deformation, aggregation and adhesion, of a lot of cells in a very complex microvascular network are taken into account. The results suggest that the tumor cells may be prone to adhere at the microvascular bifurcations with low shear rate and moderate hematocrit, because of a high wall-directed force from the surrounding RBCs. This implies that the tumor may be more likely to extravasate at the microvascular bifurcations if the blood flow is slow and the hematocrit is moderate. Our work may provide new insights into the cancer pathophysiology and its diagnosis and therapy.

Introduction

Tumor metastasis is the major cause of cancer treatment failure, where tumor cells detach from the primary site, and then spread to distant organs or other parts of the body through blood and lymphatic systems, forming the secondary tumor [1–3]. The metastasis through the blood circulation is known as hematogenous metastasis, which was reported to cause 90% death of cancer [4], and the tumor cells entering into blood circulation are so-called the circulating tumor cells (CTCs). There are several critical steps for finishing a tumor metastasis, including intravasation, margination towards the vascular wall, adhesion onto the vascular wall, and extravasation from the circulation to a distant host organ [5]. We here pay our attention to the margination and adhesion of the CTCs in a real microvascular network, for providing a deep understanding of the tumor metastasis.

The margination and adhesion are two critical and closely related steps in tumor metastasis, and generally, the former step is often regarded as a prerequisite for the latter one. Both of behaviors were firstly observed on the leukocytes [6], instead of tumor cells, and hence, most of the subsequent studies have still focused on the leukocytes [7–14]. For example, Firrell et al. [7] and Abbitt et al. [9] suggested that the margination and adhesion of a leukocyte mainly occur at low flow rates based on in vivo and in vitro experiments. Jain et al. [11] demonstrated in the microfluidic experiments that the leukocytes have obvious margination within a range of hematocrit of 20–30%, and the lower or higher hematocrit may cause less margination. Fedosov et al. [12–14] also gave the similar dependence of leukocyte margination on the flow rate and hematocrit by numerical simulations. Some other types of cells, such as platelets [15–19] and malaria-infected RBCs [20, 21], have been found to have similar margination in the vessel. So far, there are few quantitative studies on the margination and adhesion of tumor cells. King et al. [22] pointed out that the soft CTCs are marginated more slowly than the rigid CTCs, because larger deformation of the soft CTCs caused by the collisions with surrounding RBCs can prolong the time that CTCs arrive at the vessel wall. However, some experiments [23–25] have shown that the soft CTCs are more likely to extravasate from the circulation, because the soft CTCs have a large contact surface with the vascular wall and thus have a higher possibility of adhesion than the rigid CTCs. Recently, some simulation work [26, 27] has also favored the latter conclusion.

A stochastic adhesive model was developed by Hammer and Apte [28], which has been widely used to theoretically and numerically investigate the adhesion of various cells, certainly including the CTCs [27]. The model proposed that the cell adhesion is attributed to the dynamic association and dissociation between the receptors on the cell and the ligands on the vessel wall. Obviously, if the receptors and ligands contact with each other frequently, the cell is more likely to adhere to the vessel wall. But, the contact frequency depends on a lot of parameters, such as the numbers of the receptors and ligands, the shear force of fluid flow, and local force from neighboring cells [5, 29–33]. Apart from these, some studies [34–36] have shown that the cell adhesion has a considerable dependence on the microvascular geometry. For example, Liu et al. [37] observed in vivo experiments that breast cancer cells preferentially extravasate from the vessel bifurcation. More recently, Hynes et al. [36] and Pepona et al. [38] studied the metastatic behavior within a complex vasculature via both experiments and simulations, and also confirmed that CTCs are prone to attach at the branch points. However, so far there are few studies on the tumor metastasis in a complex microvascular network at a cellular scale, at which the cell deformation, aggregation and adhesion should be taken into account simultaneously [39–41]. Experimental observations at this scale are limited by the reliability of measurements and the complexity of blood flow in microvascular networks [42, 43]; numerical modeling also poses great challenges due to the poly-disperse feature of blood components and the network-like structure of microvessels [44, 45].

In the present work, we implement the direct three-dimensional modeling of tumor metastasis in a real and complex microvascular network extracted from the mesenteric microvessels of a rat. The deformation, aggregation and adhesion behaviors of cells are considered so as to deeper investigate the margination and adhesion dynamics of tumor cells. A hybrid method of smoothed dissipative particle dynamics and immersed boundary method (SDPD-IBM) is used as the main numerical methodology, which has been developed in our previous work [46]. It is found to be more suitable to solve the problems of fluid-structure interactions in a complex computational domain. The main aim of this study is to reveal the mechanism of tumor metastasis in a microvascular network, as well as the effects of hematocrit of RBCs and shear rate of blood flow.

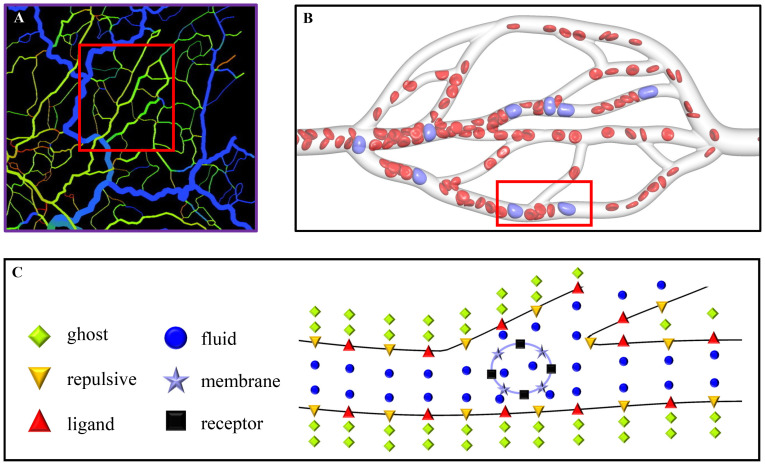

A mesenteric tumor is taken for example in the present work, and it has been found in all age groups from infancy to the very elderly [47]. Fig 1A shows a segment of real microvessels in the rat mesentery [48]. One can consider human microvessels, and there are no large differences for numerical simulations, except that the vessel configurations are required to be reconstructed. In simulations, we choose a portion of this segment to construct microvascular network model by using the commercial software “SOLIDWORKS”. This network is geometrically characterized by branching, merging and tortuous microvessels, and a small adjustment is made for getting only one outlet to suit the inflow and outflow boundary conditions used, as shown in Fig 1B. The length of the network is 260 μm, and the microvessels have circular cross section with the diameters ranging from 6.4 to 16 μm. Note that the diameter of each microvessel is calculated by Murray’s law [49], a general law for a large number of transport networks, such as the vascular systems of animals, xylem in plants, and the respiratory system of insects. The microvascular network is filled only with plasma having no cells at the initial state. In order to make cells flow into the network, a cylindrical inlet with 120 μm in length is added at its left side, and it is arranged by a large number of cells, including RBCs and CTCs. An external force is imposed only in the inlet to generate an inflow, which pushes the cells into the network. Meanwhile, a cylindrical outlet with 20 μm in length is added at its right side for handling the cells that move out from the network. Hence, the total length of the simulation domain is actually 400 μm. The RBC is modeled to be a biconcave with a maximum diameter of 7.82 μm [50], while the CTC is spherical with the diameter of 9 μm. Due to the diversity of CTCs, their sizes are very different. In experiments, Gassmann et al. [51] observed that the diameter of a tumor cell in vivo is only about 5 μm, while Guo et al. [34] gave its diameter about 16 μm. In simulations, a moderate value of 8–10 μm is often chosen for saving computational cost [26, 27, 52]. The CTC’s nucleus is also neglected for the same purpose, saving the computational cost, and this is one of limitations of our cell model. Fortunately, its effect on the CTC mechanics can be compensated to some extent by enhancing the CTC stiffness [53, 54]. The SDPD-IBM model, a particle-based method, is used as a numerical method in the present work, which discretizes the computational domain into a lot of particles. They are classified into six types in total, ghost particles, repulsive particles, fluid particles, membrane particles, receptor sites and ligand sites, respectively, as shown in Fig 1C. The ghost and repulsive particles are used to model the solid wall of the microvessels; the fluid particles are used to model the plasma and cell cytosol; the membrane particles are used to model the cell membrane; the receptor sites are scattered on the cell membrane, while the ligand sites are on the microvascular wall. The receptor and ligand sites are bonded for describing the CTC adhesion on the vascular wall. In the present work, there are 29704 ligand sites on the wall, 1176 receptor sites on the CTC’s membrane, and no receptor sites on the RBC’s membrane. It should be noted that these numbers are not same as the experimental values due to the limitation of computational resources. Hence, a coarse-grained technique is used, that is, a numerical receptor or ligand may represent several tens or hundreds of experimental receptors or ligands. The number of 29704 ligands is calculated by the fixed number density of 3 μm−2, similar with that used in the work of Zhang et al. [55], while the number of 1176 receptors is similar with that used the work of Xiao et al. [27]. The ghost particles are 93116, the repulsive particles are 181810, and the fluid particles are 88771, respectively. Each RBC has 613 membrane particles, and each CTC has 1176 membrane particles equal to receptor sites for simplicity.

Description of simulation problem.

(A) A segment of real microvessels in the rat mesentery [48], (B) the microvascular network extracted from the segment of microvessels, used as the simulation domain in the present work, and (C) the particle representation for a part of the microvascular network to show the particle discretization of the simulation domain.

Results

Overview of CTC metastasis in the network

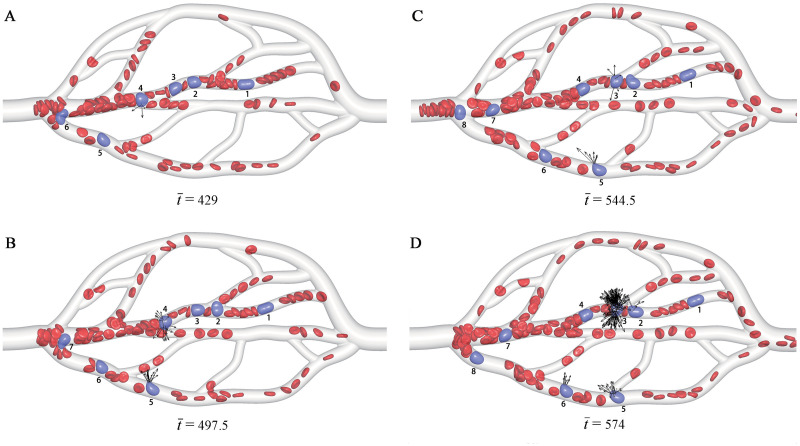

Fig 2 shows simulation snapshots of the CTCs in the microvascular network. At the initial state, there are 13 RBCs and one CTC placed into the microvascular inlet. They are driven into the microvascular network by an acceleration of , which generates a mean flow velocity of

Snapshots of the CTCs in the microvascular network at different time instants

The RBCs are in red, while the CTCs are in purple and also labeled by Arabic numerals for identification. The black arrows show the adhesion force of the CTCs. For more snapshots, see S1 Video.

Take one of CTCs for example, the CTC-4 in Fig 2. At

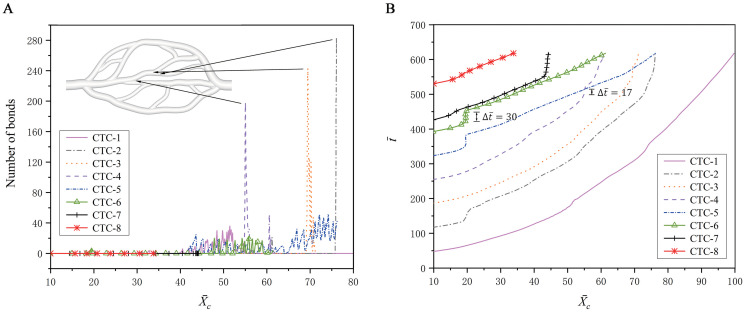

To support this conclusion, a quantitative analysis is performed by examining the variations of bond number and retention time

Adhesion behavior of the CTCs in the microvascular network.

Variations of (A) the bond number and (B) the physical time with respect to the x-position

Except the adhesion at a bifurcation, a CTC may also be adhered in a branch, e.g., the CTC-5, the CTC-6 in Fig 2, although this adhesion is not the mainstream. It is calculated that the distance between the CTC-5 centroid and the vessel wall ranges from 3.85 to 1.71 as the vessel diameter ranges from 7.7 to 5.57. That is, the CTC is deviated from the centerline of the vessel towards the wall, such that it arrives at the vessel wall completely. The similar margination behavior occurs with other CTCs, which provides more opportunities for the adhesion. The marginated CTC-5, CTC-6, CTC-7 are observed in Fig 2. Therefore, the margination is often regarded as a prerequisite for the adhesion.

Margination of a CTC in a straight tube

To fully understand the margination of CTCs, we investigate the behavior of one CTC and 49 RBCs in a cylindrical tube with the diameter of

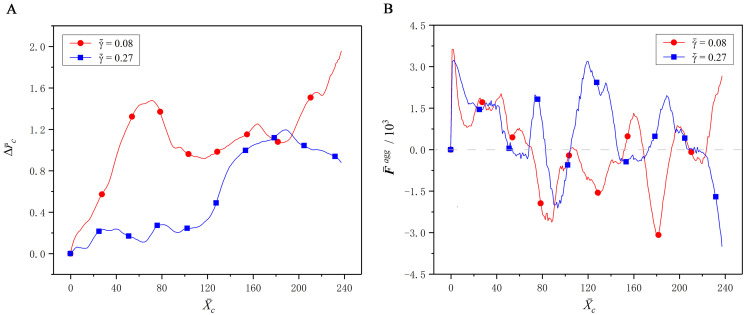

At the initial state, the CTC is placed at the tube centerline, while the RBCs are evenly distributed throughout the tube, as shown in Fig 4A. As the time elapses, the RBCs gradually migrate towards to the tube centerline, and the RBC-free layer is presented around the tube wall, as shown in Fig 4B. Meanwhile, the CTC is expelled away from the tube centerline, and an obvious margination behavior is observed in Fig 4C. This margination behavior is mainly attributed to the aggregation force acting on the CTC from the surrounding RBCs. Fig 5 shows the deviation of the CTC centroid from the tube centerline, and the radial aggregation force acting on the CTC from the RBCs. It is easily found that they are directly related. When the radial aggregation force is larger than zero, i.e., it is wall-directed, the deviation of the CTC centroid from the tube centerline continuously increases, that is, the CTC is pushed towards the vessel wall. In contrary, when this force is less than zero, i.e., it is center-directed, the CTC moves towards the tube centerline. Taking

Snapshots of the CTC margination in a straight tube.

These snapshots represent the motion states of RBCs and the CTC in the margination process. (A) The initial state, (B) RBCs move toward the center and (C) the CTC moves toward the wall.

Effect of the interaction force between the CTC and RBCs on margination behavior.

(A) The deviation

Another phenomenon is also observed from Fig 5 that as the CTC gets closer to the wall, it is pushed back towards the tube centerline to some extent. Hence, the CTC cannot, in fact, approach to the vessel wall enough to exhibit the adhesion behavior, albeit the margination observed. We call this the incomplete margination, for example, the margination of CTC at

In addition, it is also found from Fig 5 that the wall-directed force at

Adhesion of a deformable capsule on a plate

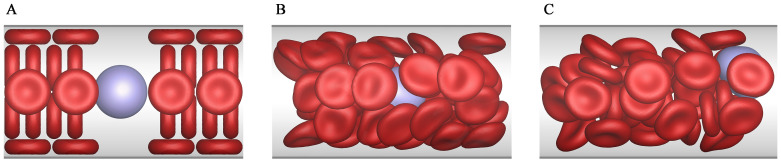

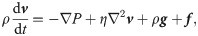

To fully understand the adhesion behavior and establish reliability of adhesion model, we investigate the adhesion behaviors of a deformable capsule, and compare the simulation results with the work of Zhang et al. [55]. The capsule is spherical with a radius of R = 3.75μm, which is placed into a cubic tube with the size 10R × 6R × 6R. A Couette flow is generated by moving the top wall of the tube with a constant shear rate

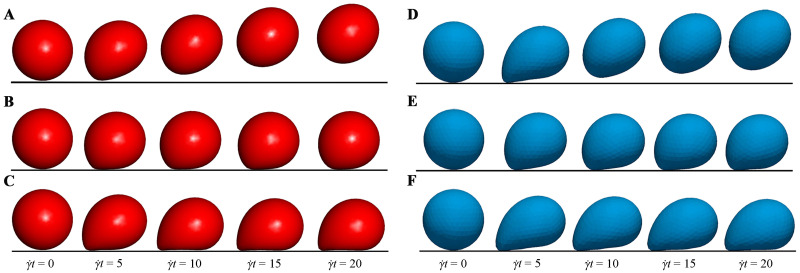

Fig 6 shows the three distinct adhesion states under Re = 0.1. At a high shear rate (Ca = 0.015) and a high dissociation rate (Kd = 1.0), the capsule detaches completely from the bottom wall and moves along the fluid flow. This state is called the detachment adhesion, as shown in Fig 6A. As the shear rate decreases (Ca = 0.005) but the dissociation rate remains unchanged (Kd = 1.0), the capsule rolls on the bottom wall, and this state is called the rolling adhesion, as shown in Fig 6B. Finally, if the dissociation rate decreases (Kd = 0.01) but the shear rate remains unchanged (Ca = 0.015), the capsule is firmly adhered onto the wall and does not move any more. This state is called the firm adhesion, as shown in Fig 6C. It is clear that our results show the same three states as those of Zhang et al. [55].

Comparisons of the three adhesion states.

Comparisons of the three distinct adhesion states between our results (A-C) and those obtained by Zhang et al. [55] (D-F) under Re = 0.1. The detachment state (A and D) is obtained under Ca = 0.015 and Kd = 1.0; the rolling adhesion state (B and E) is obtained under Ca = 0.005 and Kd = 1.0; the firm adhesion state (C and F) is obtained under Ca = 0.015 and Kd = 0.01.

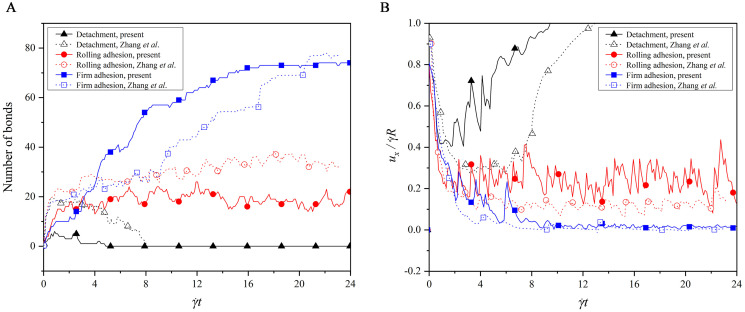

Which adhesion state is present depends on the number of bonds formed between the receptors on the cell membrane and the ligands on the bottom wall. Fig 7 shows the time evolutions of the bond number and translational velocity in the three adhesion states. In the detachment adhesion, there are a few bonds formed at the beginning, but they are all dissociated quickly. This causes the capsule to exhibit a translational velocity that decreases first and then increases to move with fluid flow. In the firm adhesion, there are about 70 bonds formed at the steady state, which hold the capsule firmly on the bottom wall with the zero translational velocity. In the rolling adhesion, there are around 20 bonds that are kept for the whole simulation, leading to a translational velocity fluctuating around a constant value. To sum up, the rate of forming the new bonds is slower than that of dissociating the existing bonds in the detachment adhesion, but the opposite is for the firm adhesion. Both the rates are in equilibrium in the rolling adhesion.

Comparisons of (A) bond number and (B) translational velocity in the three adhesion states.

In addition, a difference is noted that the bond number in our work is not exactly same as that in the work of Zhang et al. [55], as observed from Fig 7A. This difference is attributed to the difference of the deformation models used. A discrete particle model is used in our work, but Zhang et al. [55] adopted the Mooney-Rivlin model. Both models are approximated as linear at a small deformation, whereas at a large deformation, our cell has a larger deformation force than theirs if they undergoes the same deformation. That is, our model is strain hardening, while the model used by Zhang et al. [55] is strain softening. Therefore, the capsule in our work looks more rigid in each adhesion state, as shown in Fig 6, and thus they undergo the larger translational velocity in our work, as shown in Fig 7B. In the detachment and rolling adhesion, the rigid capsule is more likely to dissociate the bonds at a high dissociation rate Kd = 1.0, such that the bond number in our work is less than that in the work of Zhang et al. [55] In the firm adhesion, however, the rigid capsule is observed to have the larger contact surface with the bottom wall when its rear is firmly adhered on the bottom wall with Kd = 0.01, leading to more bonds formed in our work than that given by Zhang et al. [55] It can be found from this analysis that the cell deformation, cell adhesion and shear fluid are entangled and interact with each other.

Adhesion of a CTC in a bifurcation

As mentioned above, the CTC adhesion happens more often in a bifurcation region, and hence we here focus on its behaviors in a ‘single’ bifurcation for a deeper understanding. The bifurcation is directly extracted from the microvascular network in Fig 1B, and the effects of RBC hematocrit and shear rate of fluid on the CTC adhesion are investigated in this section.

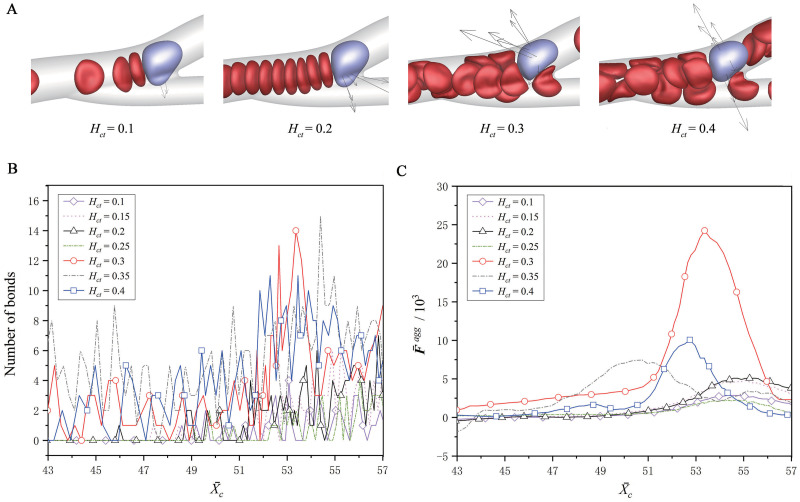

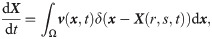

Fig 8 shows the effect of the RBC hematocrit, which is adjusted to be Hct = 10–40% by varying the number of RBCs in the microvascular inlet. The fluid flow has a mean velocity of

Effect of the RBC hematocrit on the CTC adhesion.

(A) The snapshots of the CTC at about

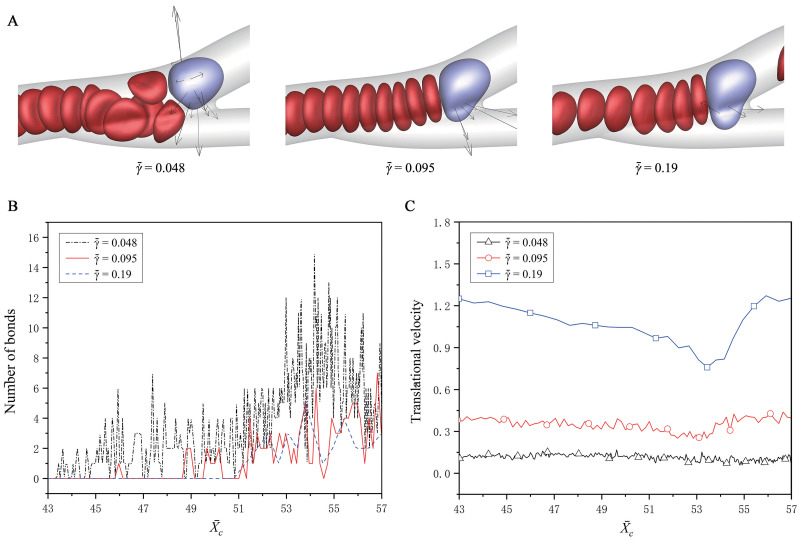

Fig 9 shows the effect of the shear rate of fluid flow, which is adjusted to be

Effect of the shear rate of fluid on the CTC adhesion.

(A) The snapshots of the CTC at about

Discussion

A direct three-dimensional simulation of tumor cells in a complex microvascular network was carried out to understand the metastasis of tumor cells as realistic as possible. The microvascular network was constructed from a real mesenteric vasculature of a rat, and comprised of bifurcating, merging and winding vessels. The cells include the red blood cells (RBCs) and circulating tumor cells (CTCs), without the platelets due to their small portion in blood. Three mechanical behaviors of cells, the deformation, aggregation and adhesion, were taken into account in the present work.

The margination and adhesion of tumor cells were mainly investigated, as well as the effects of the RBC hematocrit and flow shear rate. The simulation results showed that the tumor cells adhere more frequently at the microvascular bifurcations, and there is a positive correlation between the adhesion and wall-directed force from the surrounding RBCs. The larger the wall-directed force is, the closer the tumor cells are marginated towards the wall, and the higher the probability of adhesion behavior happen is. At a low hematocrit, e.g., 10%, the RBCs cannot provide the enough wall-directed force, because of the small RBC number, while at a high hematocrit, e.g., 40%, the wall-directed force is offset by the outer RBCs surrounding the CTC, because more RBCs exist in the vessels. Hence, a moderate hematocrit of 30% that is close to the normal level of hematocrit in a real arteriole, is found to have the largest wall-directed force, and have the largest bond number. Moreover, it is also found that the CTC margination and adhesion are enhanced as the shear rate decreases. At a low shear rate, the cells are transported slowly and aggregated easily, and the wall-directed force lasts long on a CTC. Hence, the CTC margination is more obvious at the low shear rate than at the high shear rate, and the bond number is larger, promoting the CTC adhesion.

To sum up, the present work suggests that the tumor cells may be more likely to adhere at the microvascular bifurcations with low shear rate and moderate hematocrit, because of a high wall-directed force from the surrounding RBCs. This may help to predict the location where tumor cells extravasate from the circulation, and further give new insights into the cancer pathophysiology and its diagnosis and therapy.

Methods

SDPD-IBM model for fluid flow

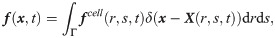

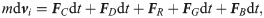

The Navier-Stokes (N-S) equations are adopted to govern the motion of the plasma and cytosol, given by [57]

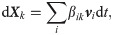

The SDPD-IBM method is used to discretize Eqs 2 and 4, and it has been already developed well in our previous work [46, 59], and here we only outline its framework for completeness. The fluid particles are evolved by

Discrete elastic model for cell deformation

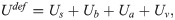

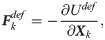

To characterize the cell deformation, the cell membrane is modeled as a triangular network by connecting all membrane particles. The edges of each triangle are modeled as springs to describe the membrane elasticity, and the angles of any two neighboring triangles are used to describe the membrane bending. Moreover, the membrane area is restrained to be varied in 3%, due to its strong membrane elasticity [60]. The cell volume is also restrained to be varied in 3%, because the material exchange is often not considered in the previous work [61–63]. As a result, the total deformation potential energy Udef of the triangular network is given by [64, 65]

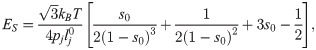

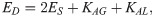

The deformation model is associated with there important macro parameters: the shear modulus ES, the bending modulus EB, and the dilation modulus ED [64],

Morse potential model for cell aggregation

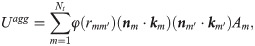

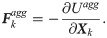

To describe the cell-cell interaction, the Morse potential model proposed by Liu et al. [66] is used, in which the total aggregation energy between the cells is approximated as [67],

Stochastic binding model for cell adhesion

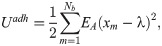

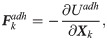

To characterize the CTC adhesion, the stochastic binding model proposed by Hammer and Apte [28] is used, in which an adhesion potential energy is given by,

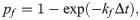

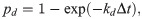

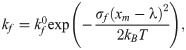

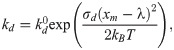

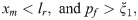

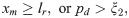

The formation and dissociation of a bond are stochastic processes, controlled by a formation probability pf and a dissociation probability pd, respectively [28],

Numerical details

There are two types of boundary conditions for Eqs 5–8, the solid boundary condition, and inflow/outflow boundary condition. The former one is applied on the microvascular wall for two purposes. One is to improve the accuracy near the microvascular wall by introducing the ghost particles. The other is to avoid the fluid and membrane particles to penetrating the microvascular wall by introducing the repulsive particles. More details about this boundary condition can be found in the work of Liu et al. [69] The inflow/outflow boundary condition is applied in the inlet/outlet of microvascular network, also for two purposes. One is to keep cells continuously moving into the microvascular network, and the other is to settle down the fluid and membrane particles that move out from the microvascular network. This boundary condition is one of advantages of our model, which not only ensures that the system including cells and fluid have reached steady states when they flow into the microvascular network, but also guarantees that the mass and momentum of the system are conserved. More details about this boundary condition can be found in our previous work [59].

A non-dimensional procedure is carried out, by choosing the cut-off radius, particle mass and Boltzmann temperature as the characteristic length l′, mass m′ and energy ϵ′. They are set as: l′ = 2 μm, m′ = 1.0 × 10−15 kg, and ϵ′ = 4.142 × 10−21 J, respectively. The other physical parameters can be scaled by these three parameters; for example, the shear modulus ES is scaled by ε′/l′2, and the bending modulus EB is directly scaled by ε′. Table 1 lists the physical parameters and their corresponding simulation values used in the present work. In the present work, we add an overline on the physical quantity (

| Physical quantities | Physical values | Characteristic quantities | Simulation values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluid density (ρ) | 1.0 × 103kg/m3 | m′/l′3 | 8 |

| Shear viscosity (η) | 1.0 × 10−4pa ⋅ s |

| 197 |

| Temperature (T) | 300K | ϵ′ | 1 |

| CTC diameter (Dt) | 9.0μm [26] | l′ | 4.5 |

| RBC diameter (Dr) | 7.82μm [50] | l′ | 3.91 |

| Shear modulus of CTC (ES) | 1.0 × 10−6N/m [71] | ϵ′/l′2 | 9.66 × 102 |

| Shear modulus of RBC (ES) | 6.0 × 10−6N/m [72] | ϵ′/l′2 | 5.794 × 103 |

| Bending modulus of CTC (EB) | 1.35 × 10−19J [73] | ϵ′ | 33 |

| Bending modulus of RBC (EB) | 2.07 × 10−19J [72] | ϵ′ | 50 |

| Dilation modulus of CTC (ED) | 1.16 × 10−4N/m† | ϵ′/l′2 | 1.12 × 105 |

| Dilation modulus of RBC (ED) | 1.26 × 10−4N/m† | ϵ′/l′2 | 1.22 × 105 |

| Equilibrium length (λ) | 0.2μm [55] | l′ | 0.1 |

| Reactive distance (lr) | 1.0μm [55] | l′ | 0.5 |

| Adhesion strength (EA) | 3.0 × 10−5N/m [55] | ϵ′/l′2 | 2.9 × 104 |

| Formation strength (σf) | 6.0 × 10−7N/m [55] | ϵ′/l′2 | 5.8 × 102 |

| Dissociation strength (σd) | 7.54 × 10−7N/m [55] | ϵ′/l′2 | 7.28 × 102 |

Unstressed formation rate ( | 1.205 × 106s−1 [55] |

| 1.205 × 103 |

Unstressed dissociation rate ( | 3.55 × 105s−1 [55] |

| 3.55 × 102 |

† The dilation modulus in simulations is, in general, smaller than real values to save computational cost, as long as it can guarantee that the variation of surface area of a RBC or tumor cell is less than 3%.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank School of Mathematics at Jilin University of China for all the supports, especially the valuable discussions with the members and the access to computational resources.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

Margination and adhesion dynamics of tumor cells in a real microvascular network

Margination and adhesion dynamics of tumor cells in a real microvascular network