- Altmetric

Among various charge‐carrier ions for aqueous batteries, non‐metal hydronium (H3O+) with small ionic size and fast diffusion kinetics empowers H3O+‐intercalation electrodes with high rate performance and fast‐charging capability. However, pure H3O+ charge carriers for inorganic electrode materials have only been observed in corrosive acidic electrolytes, rather than in mild neutral electrolytes. Herein, we report how selective H3O+ intercalation in a neutral ZnCl2 electrolyte can be achieved for water‐proton co‐intercalated α‐MoO3 (denoted WP‐MoO3). H2O molecules located between MoO3 interlayers block Zn2+ intercalation pathways while allowing smooth H3O+ intercalation/diffusion through a Grotthuss proton‐conduction mechanism. Compared to α‐MoO3 with a Zn2+‐intercalation mechanism, WP‐MoO3 delivers the substantially enhanced specific capacity (356.8 vs. 184.0 mA h g−1), rate capability (77.5 % vs. 42.2 % from 0.4 to 4.8 A g−1), and cycling stability (83 % vs. 13 % over 1000 cycles). This work demonstrates the possibility of modulating electrochemical intercalating ions by interlayer engineering, to construct high‐rate and long‐life electrodes for aqueous batteries.

Selective H3O+ intercalation is demonstrated for a water‐proton co‐intercalated α‐MoO3 cathode in a neutral ZnCl2 electrolyte, thus providing substantially enhanced specific capacity, rate capability, and cycling stability. H2O molecules between the α‐MoO3 interlayers are uncovered to block Zn2+ intercalation pathways, while allowing smooth H3O+ intercalation/diffusion through a Grotthuss proton conduction mechanism.

Introduction

Rechargeable aqueous batteries with neutral electrolytes have attracted intensive scientific attention as promising alternatives for large‐scale energy storage technologies. The utilized water‐based electrolytes offer significant advantages of high ionic conductivity (≈1 S cm−1), simplified manufacture, low cost, and intrinsic safety. [1] In particular, Zn metal batteries (ZMBs) with mild aqueous electrolytes have recently stood out, due to the direct use of Zn metal anodes with a high specific capacity (≈820 mA h g−1) and a low stripping/plating potential (−0.76 V vs. standard hydrogen electrode). [2] Numerous efforts have been devoted to exploring Zn2+‐host cathode materials of ZMBs, which has brought Mn‐compounds, V‐compounds, Prussian blue materials into the spotlight. [3] However, the Zn2+‐intercalation chemistry generally shows sluggish kinetics and unsatisfactory cycling stability. [4] In aqueous electrolytes, Zn2+ tends to form a large‐size hydrated state (Zn(H2O)6 2+ with 5.5 Å) due to the strong Zn2+‐water interaction. [5] The intercalation of Zn2+ into cathode hosts thus requires large de‐solvation and intercalation energy. Besides, bivalent Zn2+ imposes a strong repulsive force with the hosts, leading to the large Zn2+‐diffusion energy barriers within the hosts and the undesired structure distortion of hosts. [6]

Apart from Zn2+, non‐metal hydronium (H3O+) has also been recognized as favorable charge carrier ions for aqueous batteries. Assigned to the small ionic size (≈1.0 Å) and light molecular mass, H3O+ intercalation presents attractive high‐kinetics and highly reversible behaviors. [7] The partial involvement of H3O+ intercalation was also discovered for the charge‐storage mechanism of ZMB cathodes. [8] For example, Sun et al. uncovered the consequent intercalation of H3O+ and Zn2+ for ϵ‐MnO2 cathode in a mixed ZnSO4/MnSO4 electrolyte. [9] The charge‐transfer resistance of ϵ‐MnO2 in the H3O+‐intercalation step is three orders of magnitude smaller than that in the Zn2+‐intercalation step. A similar phenomenon was also observed for polyaniline‐intercalated MnO2 nanolayers, in which the diffusion coefficient of H3O+ (5.84×10−12 cm2 s−1) was substantially higher than that of Zn2+ (7.35×10−14 cm2 s−1). [10] These findings inspire that selective H3O+ intercalation into cathodes would bring the constructed ZMBs with significant performance advance in terms of capacity, kinetics, as well as cycle life. However, thus far, pure H3O+‐intercalation behavior for layered/tunneled cathodes has only been observed in corrosive acidic electrolytes.[ 7b , 11 ] It remains a grand challenge to achieve selective H3O+ intercalation in mild neutral electrolytes.

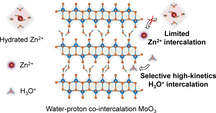

In this study, we, taking orthorhombic MoO3 (α‐MoO3) as an example, for the first time demonstrate the feasibility of selective H3O+ intercalation in a neutral ZnCl2 electrolyte. α‐MoO3 is selected due to its typical layered structure with distorted [MoO6] octahedra bilayers weakly bonded by van der Waals force. [12] The complete redox of Mo4+/Mo6+ allows α‐MoO3 with an attractive theoretical capacity of 372 mA h g−1. Selective H3O+‐intercalation chemistry is modulated for α‐MoO3 through a water‐proton co‐intercalation strategy (denoted WP‐MoO3), which further tackles the low‐capacity, poor‐rate, and short‐life issues faced by pristine α‐MoO3 with Zn2+‐intercalation chemistry. H2O molecules located between WP‐MoO3 interlayers impose a high Zn2+‐intercalation energy barrier by blocking Zn2+ diffusion pathways (Figure 1). Meanwhile, H3O+ intercalation/diffusion can be smoothly achieved within WP‐MoO3 interlayers through a well‐known Grotthuss mechanism (proton jumping between water molecules). [13] In contrast to Zn2+‐intercalation α‐MoO3, selective H3O+‐intercalation WP‐MoO3 depicts substantially enhanced redox depth (1.92 vs. 0.99 e− per Mo atom; 357 vs. 184 mA h g−1), rate capability (77.5 % vs. 42.2 % from 0.4 to 4.8 A g−1), and cycling stability (83 % vs. 13 % over 1000 cycles).

Schematic illustration of the Zn2+‐intercalation chemistry for α‐MoO3 and the selective H3O+‐intercalation chemistry for WP‐MoO3.

Results and Discussion

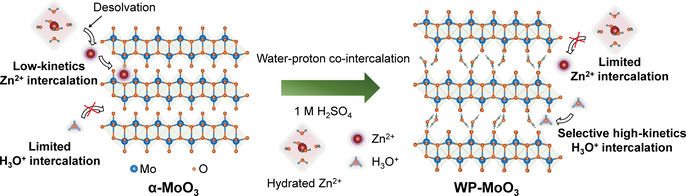

α‐MoO3 nanoparticles (Figure S1) were first synthesized through a sol‐gel method. WP‐MoO3 electrode was obtained from α‐MoO3 electrode through a controllable and time‐efficient (≈6.1 min) electrochemical linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) method (Figure S2) in a three‐electrode cell with an electrolyte of 1 M H2SO4. Compared with α‐MoO3 electrode, WP‐MoO3 displays an apparent color change from dark grey to purple (Figure S3), which is attributed to the formation of Mo4+/Mo5+ (Figure S4). [14] Almost no morphological variation was observed between α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3. The amount of intercalated H+ can be estimated by calculating the amount of charge transfer (Figure 2 a). The overall intercalation process presents four stages, referring to potential windows (vs. saturated calomel electrode (SCE)) of 0.3–−0.1 V (Stage I), −0.1–−0.34 V (Stage II), −0.34–−0.53 V (Stage III), and −0.53–−0.72 V (Stage IV). Approximately, the intercalated H+ numbers per MoO3 unit are 0.25, 0.75, 0.25, and 0.75 at Stage I, Stage II, Stage III, and Stage IV, respectively. X‐ray diffraction (XRD) spectra uncover that the peak position corresponding to the interlayer spacing of α‐MoO3 gradually shifts towards negative at Stage I and II and keeps almost unchanged at Stage III and IV (Figure 2 b & S5). This peak of WP‐MoO3 is located at 12.0°, indicating the interlayer distance expansion from 6.7 Å for α‐MoO3 to 7.6 Å (Figure S6). Besides, new peaks at 32.5°, 35.0°, and 37.1° are observed for WP‐MoO3, which indicates a monoclinic phase of proton‐intercalated MoO3. [15] The widened interlayer distance of WP‐MoO3 was also evidenced by high‐resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images, in which the interlayer spacings are determined to be 6.7 Å and 7.6 Å for MoO3 and WP‐MoO3, respectively (Figure 2 c & S7).

a) The intercalated proton amount as a function of potential during the water‐proton co‐intercalation process. b) XRD patterns of α‐MoO3 electrode at different intercalation stages. c) HRTEM images of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3. Scale bars: 5 nm. d) O 1s XPS spectra of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3. e) Illustration of different O atoms in WP‐MoO3. f) Normalized Mo K‐edge XANES spectra of MoO3 standard, Mo foil standard, α‐MoO3, and WP‐MoO3. g) Radial distribution functions of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3 obtained from the k 2 χ(k) by Fourier transform.

Figure 2 d compares the O 1s X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of MoO3 and WP‐MoO3 electrodes. Two peaks located at 532.6 eV and 531.2 eV are observed for α‐MoO3, which correspond to lattice O in MoO3 (denoted O2) and O in adsorbed H2O (denoted O1). [16] Notably, WP‐MoO3 shows an O1 peak with the substantially enhanced intensity, verifying the intercalation of H2O into WP‐MoO3. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, Figure S8) results of both electrodes also suggest the intercalated H2O molecules in WP‐MoO3. More interestingly, an additional XPS peak at 530.2 eV (denoted O3) is observed for WP‐MoO3. This peak can be assigned to the terminal O of [MoO6] bilayers, which splits from O2 peak due to the formation of the hydrogen bond with the intercalated H2O/H3O+ (as illustrated in Figure 2 e). Furthermore, synchrotron‐based X‐ray absorption near‐edge spectra (XANES) measurements were performed to investigate the localized coordination environments of Mo sites in α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3. The Mo K‐edge XANES spectra of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3, as well as standard Mo foil and MoO3 as references, are displayed in Figure 2 f. In comparison with α‐MoO3, the slightly negative‐shifted rising‐edge of WP‐MoO3 around 20 015 eV suggests the enriched electron densities around Mo sites. [17] This result is consistent with the analysis of O K‐edge XANES spectra, which witness the decreased peak intensity of WP‐MoO3 at the energy region of 530–540 eV (Figure S9). [18] In addition, the Mo pre‐edge of WP‐MoO3 around 20 007 eV, referring to the O 1s‐Mo 4d electron transfer, is obviously decreased compared with that of α‐MoO3, reflecting the interaction between the terminal O of [MoO6] bilayers and the intercalated species (i.e., H2O and H3O+). [19] To acquire the detailed bonding and coordination information, corresponding R space curves after k 2[χ(k)]‐weighted Fourier transform of the extended X‐ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and quantitatively fitting spectra are presented in Figure 2 g & S10. Two representative peaks at 1.16 and 1.69 Å can be assigned to the scattering of Mo=O and Mo−O bonds in [MoO6] bilayers, respectively. [20] These two peaks are also indicated in Figure 2 e. Both Mo=O and Mo−O bonds show negligible length difference between α‐MoO3 (1.72 & 1.96 Å) and WP‐MoO3 (1.73 & 1.97 Å), implying the water‐proton pre‐intercalation causes minor distortion of octahedron [MoO6] layers. Moreover, the coordination number of Mo−O (from 1.8 to 1.4) and Mo=O (from 2.0 to 1.4) decreases due to the water‐proton co‐intercalation, which again verifies the interaction between the terminal O of [MoO6] bilayers and the intercalated H2O/H3O+.

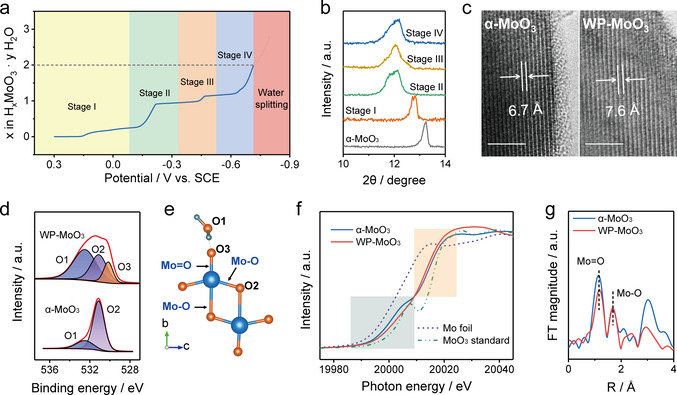

The ion‐intercalation behaviors of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3 electrodes were explored in two‐electrode cells with Zn foil as the anode and 2 M ZnCl2 aqueous solution as the electrolyte. Figure 3 a and Figure 3 b present the galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD) curves of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3 electrodes after three‐cycle activation at 0.4 A g−1. Both electrodes show two mainly ion‐intercalation stages in their discharge curves, which agrees well with the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves (Figure S11). In detail, α‐MoO3 electrode presents a discharge curve consisting of one plateau region (Plateau I, ≈0.62 V) and one slope region (Slope I, 0.25–0.35 V), while WP‐MoO3 electrode presents two plateaus around 0.68 V (Plateau I) and 0.30 V (Plateau II). Impressively, WP‐MoO3 electrode exhibits a high redox depth of 1.92 e− per Mo atom, close to the full conversion of Mo4+/Mo6+. By contrast, a shallow redox depth of 0.99 e− per Mo atom is achieved by α‐MoO3 electrode.

GCD profiles of a) α‐MoO3 and b) WP‐MoO3 electrodes at a current density of 0.4 A g−1. Electrode mass change versus charge during the discharge (ion‐intercalation) processes of c) α‐MoO3 and d) WP‐MoO3 electrodes. EDX elemental mapping of e) α‐MoO3 and f) WP‐MoO3 at the fully discharged state. Scale bars: 50 nm.

Electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) was employed to in‐operando monitor the mass evolution of MoO3 and WP‐MoO3 along with the continuous ion intercalation. In consistent with the discharge curves, the mass change of both electrodes during ion intercalation depicted two stages. At the first stage of α‐MoO3, the average weight increase calculated by the curve slope (Figure 3 c) is 45 g per mol charge, which suggests the co‐intercalation of Zn2+ and H2O into α‐MoO3 (Zn2+⋅1.5 H2O in average). Meanwhile, the average weight increase of α‐MoO3 at the second stage is 18 g per mol charge, close to the weight of H3O+ (19 g per mol charge). Clearly, Zn2+/H2O co‐intercalation plays the dominant role in the charge‐storage mechanism of α‐MoO3. By contrast, WP‐MoO3 depicts the weight increase of 19 and 18 g per mol charge at the two stages (Figure 3 d), verifying the selective H3O+‐intercalation chemistry of WP‐MoO3 in 2 M ZnCl2 electrolyte. This result means although Zn2+ is the mainly charge carrier in the electrolyte, the charge carrier only consists of H3O+ in WP‐ MoO3 electrode, which comes from the pre‐stored H+ in WP‐MoO3 and the slight hydrolysis of ZnCl2 in the electrolyte. However, the local Zn2+ concentration near the surface of WP‐MoO3 should be increased during discharging, because Zn2+ tends to migrate to the Helmholtz layer of WP‐MoO3 due to the electrostatic interaction.

The interesting H3O+‐intercalation behavior of WP‐MoO3 is further supported by the Energy‐dispersive X‐ray spectroscopy (EDX) elemental mapping analysis. The fully discharged α‐MoO3 presents the even distribution of Mo and Zn over the sample (Figure 3 e & S12), while Zn distribution is barely observed in WP‐MoO3 (Figure 3 f & S12). The Zn/Mo atomic ratio of the discharged WP‐MoO3 is calculated to be 0.02, which contrasts with the high Zn/Mo atomic ratio of the discharged α‐MoO3 (0.48). Moreover, the discharged α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3 were annealed in air at 500 °C and subjected for XRD measurements (Figure S13). Peaks refer to ZnMoO3 are only detected for the discharged α‐MoO3, rather than for the discharged WP‐MoO3. All these results identify the successful modulation of intercalating charge carriers for α‐MoO3, which brings the obtained WP‐MoO3 with exceptional selective H3O+‐intercalation chemistry in a neutral electrolyte.

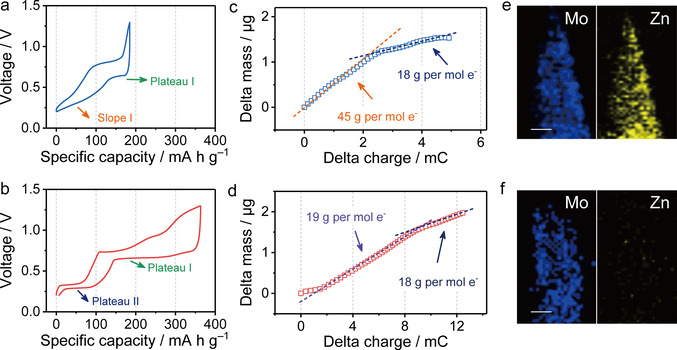

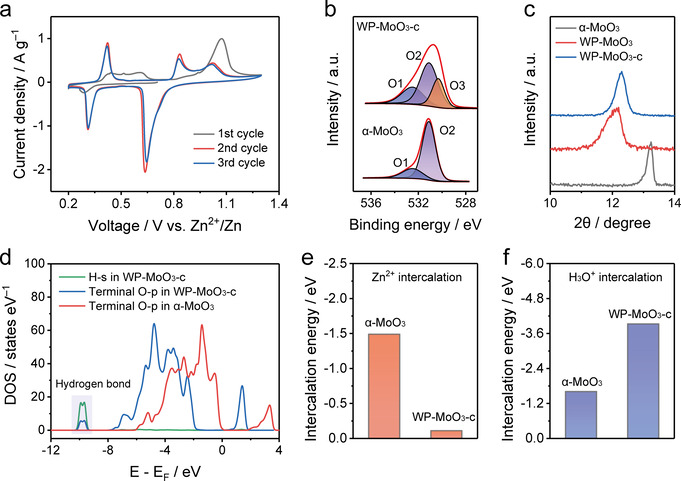

To understand the origin of the selective H3O+‐intercalation behavior, the first three CV cycles of WP‐MoO3 electrode were recorded as shown in Figure 4 a. In the initial cycle, only a small cathodic peak is observed during the discharge process, whereas the charge process displays four anodic peaks corresponding to the extraction of the pre‐intercalated H3O+ and H2O. Afterwards, WP‐MoO3 electrode presents almost the identical 2nd and 3rd cycles (Figure S14), which include three anodic peaks and three cathodic peaks. The cathodic peaks and anodic peaks can be assigned to the H3O+ intercalation and de‐intercalation, respectively. Based on the CV curves, the charge transfer number of the first two pairs of redox peaks is calculated to be 1.495 (close to 1.5), implying the conversion between Mo6+ and Mo5+/Mo4+ (1:1). Meanwhile, the charge transfer of the third pair of redox peaks is 0.498 (close to 0.5), which refers to the conversion between Mo5+/Mo4+ (1:1) and Mo4+. In this regard, the structure of WP‐MoO3 after the first cycle (denoted WP‐MoO3‐c) is of significance to induce the selective H3O+ intercalation of WP‐MoO3 electrode. The Mo 3d XPS spectrum of WP‐MoO3‐c uncovers the existence of Mo5+ in WP‐MoO3‐c (Figure S15), indicating that H+ ions were not fully extracted from the lattice. This result is further supported by the observation of O3 peak in the O 1s XPS of WP‐MoO3‐c (Figure 4 b). The partial extraction of H2O was verified by the larger O1 peak intensity of WP‐MoO3‐c than that of α‐MoO3, as well as the TGA analysis (Figure S16). Moreover, the interlayer distance of WP‐MoO3‐c identified by the XRD peak position only slightly decreased from 7.6 Å for WP‐MoO3 to 7.4 Å, which remains to be significantly larger than that of α‐MoO3 (6.7 Å) (Figure 4 c & S17).

a) Initial three CV cycles of WP‐MoO3 at 0.7 mV s−1. b) O 1s XPS spectra of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3‐c. c) XRD patterns of α‐MoO3, WP‐MoO3, and WP‐MoO3‐c. d) Simulated PDOS of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3‐c. Calculated e) Zn2+‐intercalation energy and f) H3O+‐intercalation energy for α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3‐c.

Based on the quantitive analysis of XPS results, the structures of α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3‐c (Figure S18) were simulated with the density functional theory (DFT) method. In WP‐MoO3‐c, the bonding interaction between the residual intercalant (i.e., H2O and H3O+) and the terminal O of [MoO6] bilayers is proved by the formant arise at −10 eV in projected density of states (PDOS) of terminal O‐p orbital with H‐s orbital (Figure 4 d). This bonding interaction greatly influence the electron density of terminal O atoms, which agrees well with the O 1s XPS results of our samples. Additionally, WP‐MoO3 has a band gap of 0.04 eV, which is remarkably smaller than that of α‐MoO3 (2.18 eV). The Fermi level of WP‐MoO3 also shifts to the conduction band, favoring the excitation of charge carriers to the conduction band and thus the improved electronic conductivity (Figure S19). [21]

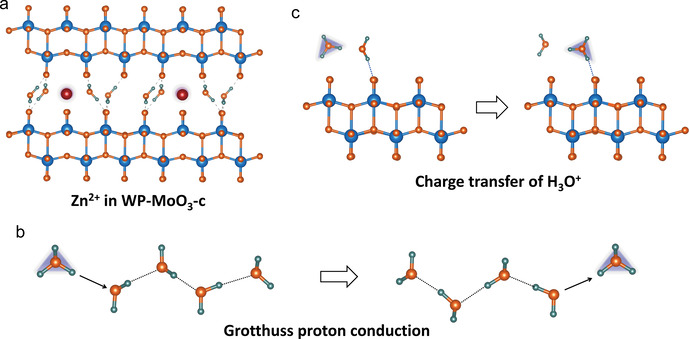

Subsequently, the Zn2+‐intercalation energy (Figure 4 e) and H3O+‐intercalation energy (Figure 4 f) were calculated for α‐MoO3 and WP‐MoO3‐c. As expected, a substantially enlarged Zn‐intercalation energy is uncovered for WP‐MoO3‐c (−0.11 eV) in comparison to α‐MoO3 (−1.49 eV), while the H3O‐intercalation energy of WP‐MoO3‐c (−3.93 eV) is notably lower than that of α‐MoO3 (−1.61 eV). These results confirm the thermodynamically preferable H3O+ intercalation into WP‐MoO3‐c. Besides, the residual H2O and H3O+ located in the interlayer space and bonded with terminal O atoms of [MoO6] bilayers block the Zn2+‐diffusion pathways in WP‐MoO3‐c (Figure 5 a) and hinder the charge transfer through the interaction with [MoO6] bilayers (Figure S20 & 21). In the case of H3O+ intercalation into WP‐MoO3‐c, charge carrier diffusion can be efficiently achieved through a well‐established Grotthuss mechanism (Figure 5 b), in which protons can be fast transported by “jumping” through water molecules. [22] Proton conductivities measurement (Figure S22) shows that WP‐MoO3‐c owns a proton conductivity value of 4.3×10−3 S cm−1 at 318 K and 100 % humidity, which is much higher than α‐MoO3 (6.2×10−5 S cm−1). Moreover, WP‐MoO3‐c also shows an activation energy (E a) of 0.28 eV, which suggests the Grotthuss conduction mechanism (E a<0.4 eV). [23] H2O molecules between the interlayers serve as the proton transport intermedia, providing a hydrogen‐bonding network for the high‐kinetics charge carrier diffusion. [24] Moreover, the charge transfer from H3O+ to WP‐MoO3‐c can be also through Grotthuss mechanism without breaking the hydrogen bonding interaction between H2O and the terminal O of [MoO6] bilayers (Figure 5 c). Thereby, the unique van der Waals structure of WP‐MoO3‐c favors the selective H3O+‐intercalation behavior both thermodynamically and kinetically.

a) Schematic illustration of Zn2+ inserted WP‐MoO3‐c. b) Schematic illustration of the Grotthuss proton‐conduction mechanism. Protons are transported by rearranging bonds along a water chain. c) Schematic illustration of the charge transfer of H3O+ via Grotthuss mechanism.

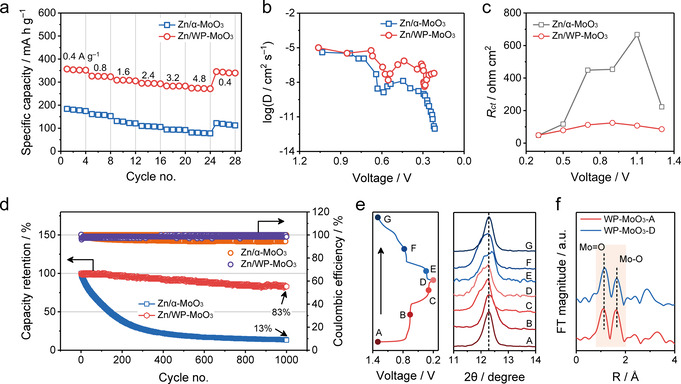

The selective H3O+ intercalation of WP‐MoO3 electrode motivated us to assess the electrochemical performance of ZMB devices assembled by coupling Zn anodes with WP‐MoO3 cathodes (denoted Zn/WP‐MoO3). ZMB devices based on Zn2+‐intercalation α‐MoO3 cathodes were also constructed for comparison (denoted Zn/α‐MoO3). GCD curves at various current densities were collected to evaluate both devices (Figure S23). As shown in Figure 6 a, Zn/α‐MoO3 only exhibits a specific capacity of 184.0 mA h g−1 at 0.4 A g−1 (based on the cathode) and a capacity retention of 42.2 % at 4.8 A g−1. By contrast, Zn/WP‐MoO3 delivers a much larger specific capacity (356.8 mA h g−1 at 0.4 A g−1) and a greatly improved rate capability (77.5 % from 0.4 to 4.8 A g−1). When the current density returns to 0.4 A g−1 after the rate tests, Zn/WP‐MoO3 can still show a specific capacity of 345.6 mA h g−1. The influence of different amounts of intercalated H+ (from 0.25 to 2.0 per MoO3) on the electrochemical performance was also investigated by preparing a series of WP‐MoO3 electrodes with different cut‐off potentials (Figure S24). In brief, the larger amount of intercalated H+ results in the higher specific capacity of the obtained Zn/WP‐MoO3 devices. Importantly, Zn/WP‐MoO3 delivers the maximum energy density of 198.0 Wh kg−1 (based on the cathode) at a power density of 0.28 kW kg−1, as well as the peak power density of 6.7 kW kg−1 at a high energy density of 104.5 Wh kg−1. These energy and power densities significantly outperform those of the recently reported ZMBs based on cathodes like MnO2, [3c] ZnMn2O4, [25] VS2, [26] ZnHCF, [27] and pyrene‐4,5,9,10‐tetraone [28] (Figure S25). It should be noticed that the energy contribution of plateau II (≈0.30 V) is only about 16.8 % in Zn/WP‐MoO3 (Figure S26), while most of the energy is contributed by plateau I (≈0.68 V). The outstanding performance of Zn/WP‐MoO3 originates from H3O+ charge carriers, which allow the high‐kinetics diffusion and the efficient charge transfer. Figure 6 b displays the calculated charge carrier diffusion coefficients of Zn/α‐MoO3 and Zn/WP‐MoO3 devices based on a galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT, Figure S27). Both devices exhibit low charge carrier diffusion coefficients at voltages associated with ion‐intercalation stages. As expected, Zn/WP‐MoO3 with H3O+ charge carriers achieves high diffusion coefficients of 1.6×10−8 cm2 s−1 at 0.57 V and 4.4×10−9 cm2 s−1 at 0.29 V, which are several orders of magnitude higher than those of Zn/α‐MoO3 with Zn2+ as the main charge carrier (1.2×10−9 cm2 s−1 at 0.58 V and 1.3×10−12 cm2 s−1 at 0.22 V). In addition, the low charge transfer resistance (R ct) of Zn/WP‐MoO3 derived from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS, Figure S28) reflects the efficient charge transfer enabled by H3O+ charge carriers. As shown in Figure 6 c, R ct of Zn/WP‐MoO3 ranges from 48.9 to 124.5 Ω, which contrasts with that of Zn/α‐MoO3 (48.1 to 667.3 Ω).

a) Rate performance, b) ion diffusion coefficient as a function of the voltage during the discharge, c) R ct at different voltages, and d) cycling performance at 3.2 A g−1 of Zn/α‐MoO3 and Zn/WP‐MoO3 devices. e) Ex situ XRD of WP‐MoO3 during one discharge/charge cycle of Zn/WP‐MoO3. f) Radial distribution functions obtained from the k 2 χ(k) by Fourier transform of XANES of WP‐MoO3 cathode at the charged (WP‐MoO3‐A) and discharged (WP‐MoO3‐D) states.

The cycling stability of Zn/α‐MoO3 and Zn/WP‐MoO3 was evaluated at a current density of 3.2 A g−1. Zn/WP‐MoO3 presents impressive coulombic efficiencies of nearly 100 %, which indicates its high charge/discharge reversibility. In contrast with the fast capacity decay of Zn/α‐MoO3 (13 % capacity retention after 1000 cycles), Zn/WP‐MoO3 can maintain 83 % of the initial capacity after 1000 cycles (Figure 6 d). The outstanding cycling performance of Zn/WP‐MoO3 is assigned to the negligible structure distortion of WP‐MoO3 during the repeated H3O+ intercalation/extraction. In the ex‐situ XRD tests of WP‐MoO3 cathode during one discharge/charge cycle of Zn/WP‐MoO3, the peak position located at 12.3° of WP‐MoO3 only experiences slight shift, indicating the little volume expansion/shrinkage of WP‐MoO3 in direction which is perpendicular to interlayer (Figure 6 e). Moreover, Mo‐K edge XANES (Figure S29) and corresponding Fourier transforms of the Mo K‐edge k 2 χ(k) spectra (Figure 6 f) confirm that both Mo=O and Mo−O bonds of WP‐MoO3 cathode have no change in bonding length at the fully charged and discharged stages. All these results imply that the selective H3O+‐intercalation chemistry is able to empower electrodes with large specific capacity, high charge‐storage kinetics and long cycle life.

Conclusion

In summary, we have uncovered an exceptional selective H3O+‐intercalation chemistry for WP‐MoO3 electrode in a neutral ZnCl2 electrolyte. The interesting charge‐carrier‐selection behavior of WP‐MoO3 originated from the interlayer species (i.e., H2O, H3O+) of WP‐MoO3, which allowed the fast‐kinetics transport and charge transfer of H3O+ while blocking Zn2+ intercalation. This study provides a novel charge‐carrier‐modulation concept through the strategic van der Waals structure engineering, which opens a promising prospect for developing high‐kinetics and long‐life battery technologies.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21822509, U1810110, and 21802173), Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong Province (2018A050506028), and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030310301). The authors acknowledge the numerical calculation use of supercomputing system in the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China and TianHe‐2 supercomputing system in National Supercomputing Center in Guangzhou (NSCC‐GZ). The authors also thank the Photoemission Endstations (BL10B) in National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) and the BL14W1 beamline in Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF) for help in characterizations. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

1

1a

1b

1c

2

2a

2b

2c

3

3a

3b

3c

3d

4

4a

4a

4b

4b

4c

5

6

7

7a

7a

8

8a

9

11

11a

11b

11b

12

12a

12a

12b

13

14

14a

15

16

16a

16b

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

24a

24b

25

26

27

28

28

Interlayer Engineering of α‐MoO3 Modulates Selective Hydronium Intercalation in Neutral Aqueous Electrolyte

Interlayer Engineering of α‐MoO3 Modulates Selective Hydronium Intercalation in Neutral Aqueous Electrolyte