Author Contributions: S.A, H.A.F, L.P, and M.R.S conceptualised the study. S.A and M.R.S performed altimetry data processing. B.C.M conducted climate and firn modelling. All authors contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. H.A.F, B.C.M, L.P, and M.R.S contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

Ocean-driven basal melting of Antarctica’s floating ice shelves accounts for about half of their mass loss in steady-state, where gains in ice shelf mass are balanced by losses. Ice shelf thickness changes driven by varying basal melt rates modulate mass loss from the grounded ice sheet and its contribution to sea level, and the changing meltwater fluxes influence climate processes in the Southern Ocean. Existing continent-wide melt rate datasets have no temporal variability, introducing uncertainties in sea level and climate projections. Here, we combine surface height data from satellite radar altimeters with satellite-derived ice velocities and a new model of firn-layer evolution to generate a high-resolution map of time-averaged (2010–2018) basal melt rates, and time series (1994–2018) of meltwater fluxes for most ice shelves. Total basal meltwater flux in 1994 (1090±150 Gt/yr) was not significantly different from the steady-state value (1100±60 Gt/yr), but increased to 1570±140 Gt/yr in 2009, followed by a decline to 1160±150 Gt/yr in 2018. For the four largest “cold-water” ice shelves we partition meltwater fluxes into deep and shallow sources to reveal distinct signatures of temporal variability, providing insights into climate forcing of basal melting and the impact of this melting on the Southern Ocean.

The mass budget of the Antarctic Ice Sheet is primarily controlled by mass gain from net snow accumulation and mass loss from basal melting and iceberg calving of its floating ice shelves. These ice shelf mass loss processes act to maintain the ice shelf in steady state; however, many ice shelves are experiencing net mass loss1 and thinning2 due to ocean-driven basal melting in excess of the steady-state values. Confined ice shelves reduce the speed of grounded ice flowing into them by exerting back-stress from sidewall friction and basal pinning points, a process called “buttressing”3. Excess basal melting in recent decades has reduced buttressing and increased dynamic mass loss of grounded ice, which has increased Antarctica’s contribution to sea level rise4,5.

Ice shelf melting has been categorized into three modes corresponding to distinct oceanographic processes6. Mode 1 melting occurs at the deep grounding lines of “cold-water” ice shelves, and is driven by inflows of cold, dense High Salinity Shelf Water (HSSW) that is produced through sea ice formation on the continental shelf7. Rising plumes of buoyant and potentially supercooled meltwater (referred to as Ice Shelf Water; ISW) formed from Mode 1 melting can lead to refreezing downstream, creating a layer of “marine ice” on the ice shelf base8. Mode 2 melting occurs at “warm-water” ice shelves where a subsurface layer of warm Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) or modified CDW (mCDW) is transported into the ice-shelf cavity. Mode 3 melting occurs near the ice front where seasonally warmed Antarctic Surface Water (AASW) can be transported under shallow ice by tides and other modes of ocean variability. The relative contributions of these modes to total melting are highly variable around Antarctica, both in space and time, since each mode is influenced by several external processes including regional atmospheric and oceanic conditions and the production and transport of sea ice9,10.

The changing net fluxes and distribution of freshwater from ice shelf basal melting influence other components of the climate system through processes such as: the production and extent of sea ice, which modifies the exchange of heat, freshwater, and gases (e.g., CO2) between the atmosphere and Southern Ocean11,12; formation of Antarctic Bottom Water that is a major driver of the global ocean overturning circulation13; and generation of nearshore coastal currents that advect freshwater and other tracers to connect different regions around Antarctica14,15. Despite the projected impacts of changes in ice shelf melting on Southern Ocean dynamics and global climate variability16, the current generation of global climate models such as those used in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project17 do not include realistic representations of meltwater fluxes18.

Satellite-derived estimates of basal melt rates

Currently, the best available circum-Antarctic datasets for ice shelf basal melt rate are derived from Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) laser altimetry acquired during 2003–200819,20. These estimates are six-year averages for the satellite’s operational period, with no information about temporal variability. Although ICESat’s orbit to 86°S sampled all Antarctic ice shelves, it had relatively wide cross-track spacing, particularly for the northerly ice shelves (Figure S1). Existing data therefore cannot capture critical properties of meltwater fluxes from ice shelves, such as small spatial scales of melting in channels21,22 or the large decadal variability inferred from oceanographic observations in West Antarctica4.

A sequence of four European Space Agency satellite missions carrying radar altimeters have continuously acquired ranging data that allow us to estimate surface height change over Antarctica’s ice shelves from 1994 to 2018: ERS-1, ERS-2, and Envisat (1992–2010) to 81.5°S and CryoSat-2 (2010–) to 88°S. CryoSat-2 samples all ice shelf areas, with higher track density than prior altimeters (Figure S1). Together with its innovative Synthetic Aperture Radar-Interferometric (SARIn) mode of operation23, the orbit for CryoSat-2 allows for estimating height change with higher spatial resolution and accuracy than the previous radar altimeters22. Here, we estimate time-averaged (over eight years; 2010–2018) basal melt rates at high spatial resolution (500-m grid cells) for all ice shelves where sufficient data are available by combining height changes from CryoSat-2 radar altimetry with satellite-derived ice velocities and a new model of surface mass balance and firn state variability (Methods). We then use the continuous height record from the four altimetry missions to estimate basal melt rates in 10-km grid cells for every year from 1994 to 2018 for all Antarctic ice shelf regions where sufficient data are available.

Spatial distribution of basal melt rates

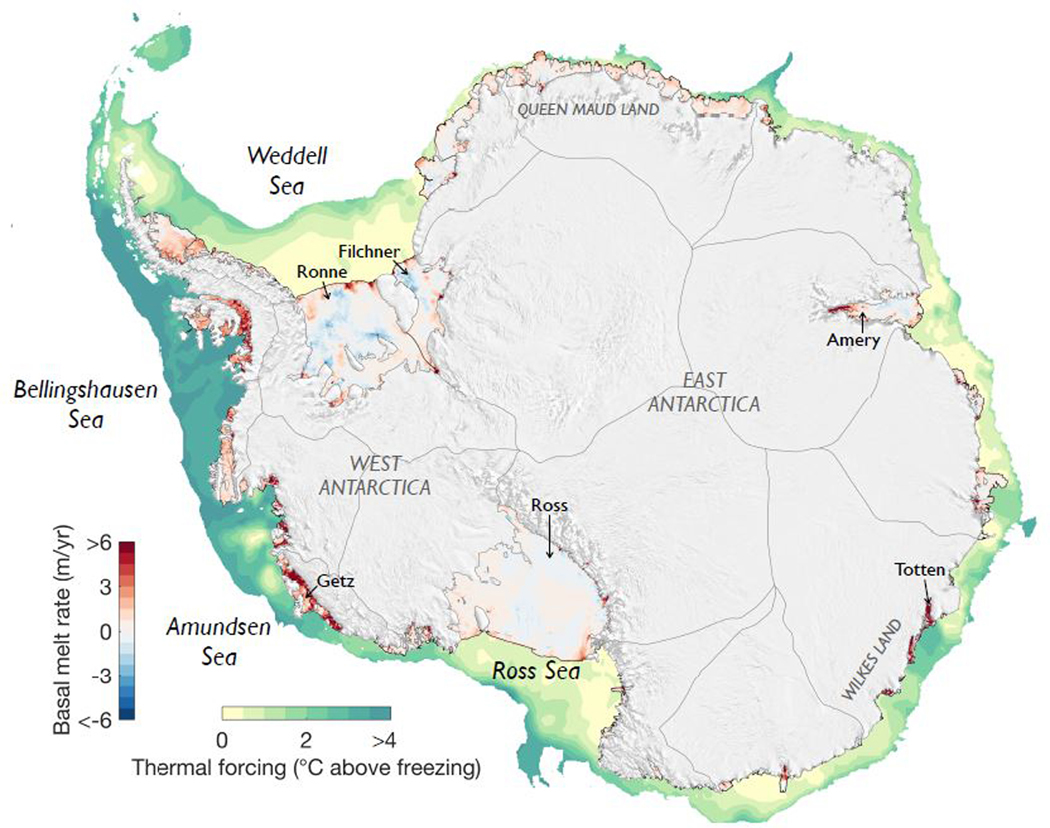

The spatial distribution of time-averaged ice shelf melt rates around Antarctica during 2010–2018 (Figure 1) shows large differences between warm- and cold-water ice shelves. Cold-water ice shelves (such as Ross, Ronne, Filchner, and Amery) show high melt rates under thick ice near grounding lines and thin ice near ice fronts (Figure 1, ice draft shown in Figure S2) separated by zones of refreezing. Warm-water ice shelves such as those in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen seas typically have high melt rates, consistent with the higher values of thermal forcing (temperature above the pressure-dependent, in situ freezing point of seawater) found near their ice fronts.

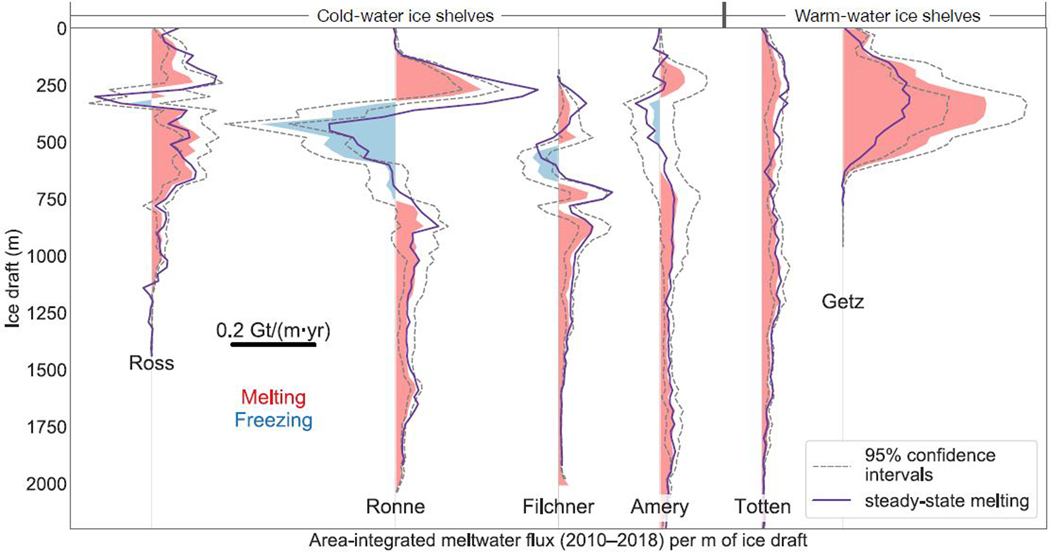

Area-integrated meltwater fluxes binned by ice draft for four cold-water and two warm-water ice shelves (Figure 2) provide further insight into the different modes of melting occurring at different locations. Melting for regions of deep ice draft under the large cold-water ice shelves is dominated by Mode 1 processes. In steady state, refreezing rates can be high, and about half of all Mode 1 meltwater produced under Ronne Ice Shelf and about a fifth of all meltwater produced under Amery Ice Shelf is subsequently refrozen as marine ice. The predicted thickness of marine ice estimated from our refreezing rates for Ronne and Amery ice shelves agrees well with independent estimates from airborne radar sounding and satellite radar altimetry (Figure S3). Refreezing typically starts at ice drafts that are around 50% of the grounding line depth, consistent with predictions from idealized models that use buoyant plume theory24,25. The ranges of ice draft for regions with refreezing (Figure 2) also correspond with the approximate depths for the subsurface plumes of cold ISW found along ice fronts26–28, which subsequently contribute to the formation of AABW29.

Cold-water ice shelves also have regions of relatively high basal melt rates under shallower ice along the ice fronts (Figure 1, 2), primarily due to Mode 3 melting. Unlike regions undergoing Mode 1 melting that are close to the deep grounding lines where ice shelf thinning could substantially reduce buttressing30,31, regions of Mode 3 melting are typically within the “passive ice zones”32 that provide little buttressing to grounded ice. However, the elevated melt rates contribute to increased ocean stratification along the ice front that influences cross-front exchanges of ocean heat33 and the seasonal cycle of sea ice formation close to the ice front34, both of which feed back into the seasonal cycle of ice shelf melt rates35,36.

Under warm-water ice shelves, high melt rates are associated with subsurface flows of CDW and mCDW (Mode 2 melting). Melting in excess of steady state caused rapid thinning of several warm-water ice shelves in the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Sea sectors during 2010–2018 (Figure S4). For some ice shelves in these sectors (e.g., George VI, Wilkins, and Dotson) the highest rates of thinning occurred in narrow basal channels with high melt rates. Getz Ice Shelf, the largest single source of meltwater from the Antarctic ice shelves (Table S1), shows excess melting at depths between 250 m and 700 m (Figure 2). Warm-water ice shelves outside the Amundsen and Bellingshausen seas sector, such as Totten Ice Shelf in East Antarctica, show insignificant rates of excess melting.

Variations in ice shelf melt rates between 1994 and 2018

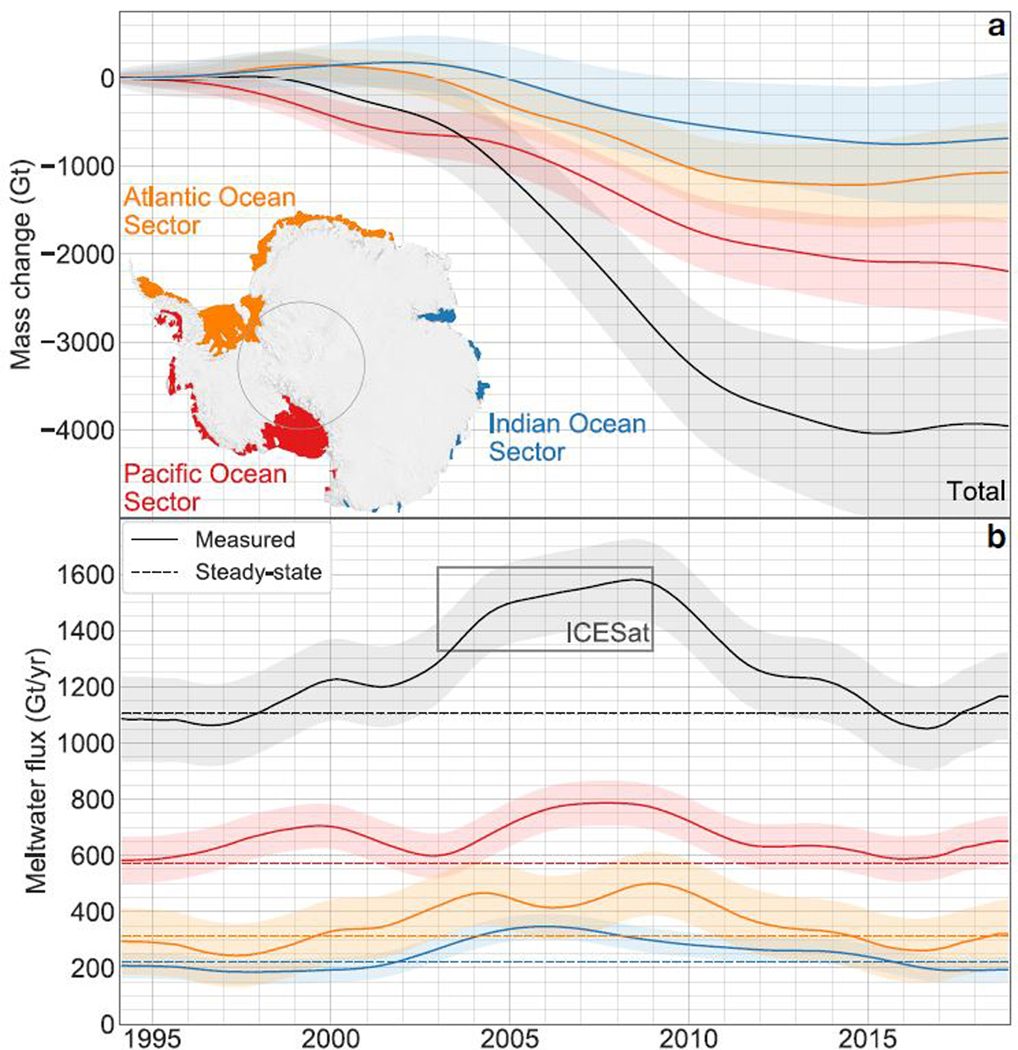

Our estimate for net mass loss from all of Antarctica’s ice shelves from 1994 to 2018 is 3960±1100 Gt (Figure 3a; error range is the 95% confidence interval, Section S5). Most of this mass loss was from the Pacific Ocean Sector ice shelves. For reference, the net loss of grounded ice from the Antarctic Ice Sheet during 1992–2017 was 2660±560 Gt37. The total meltwater flux, based on the area-integrated basal melt rate over all Antarctic ice shelves averaged over 1994–2018, was 1260±150 Gt/yr, which was 160±150 Gt/yr higher than the steady-state rate of 1100±60 Gt/yr (Figure 3b). Meltwater fluxes varied substantially with time: an increase of 480±210 Gt/yr, from 1090±150 Gt/yr at the start of the record in 1994 to 1570±140 Gt/yr in 2009 was offset by a subsequent decrease of 410±210 Gt/yr to 1160±150 Gt/yr in 2018. Our estimate of time-averaged meltwater flux for the ICESat-era (2003–2008) is 1500±140 Gt/yr, which is consistent with two previous ICESat-based estimates of 1500±240 Gt/yr19 and 1450±170 Gt/yr20. The ICESat-era estimate of meltwater flux exceeds our 25-year average by 240±210 Gt/yr, and exceeds our steady-state estimate by 400±160 Gt/yr, highlighting the importance of long, continuous records to provide context to results from individual missions1 or between two non-overlapping missions38.

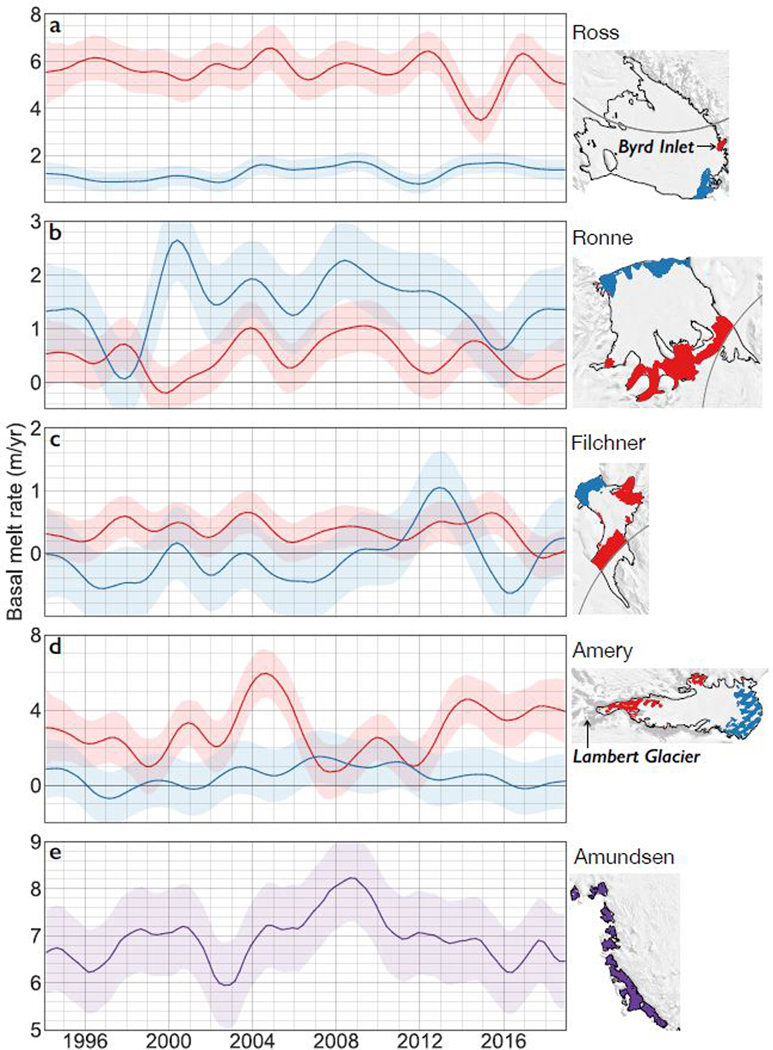

We examined the temporal variability in melt rates from different modes for the four largest cold-water ice shelves by calculating spatial averages over select regions (Figure 4a-d) of deep ice draft (Mode 1) and shallow draft (mostly Mode 3). For Ross Ice Shelf, the timing of the minimum in Mode 1 melt rates in Byrd Inlet near 2015 is consistent with the 2013–2014 minimum in HSSW salinity on the Ross Sea continental shelf39 and the time scale for advection of HSSW to Byrd Glacier36. Lower salinity for HSSW reduces the negative buoyancy driving HSSW under the ice front and downslope to the deep grounding line of Byrd Glacier, weakening the circulation of HSSW into Byrd Inlet and the resulting melting. Mode 1 melting of Filchner and Ronne ice shelves has been hypothesized to have increased following the formation of an exceptionally large polynya during the 1997–1998 austral summer40. This hypothesis was based on a sharp decline in ocean temperatures at an instrumented site (Site 5; Figure S5) on Ronne Ice Shelf near the southwestern Berkner Island coast between 2000 and 2003, attributed40 to increased ISW formation following a period of high Mode 1 melting. Our data also support this hypothesis, with increased melt rates at deep ice drafts under Filchner Ice Shelf during 1999–2000 and decreased melt rates (including a short-lived transition to refreezing) at Site 5 between 2000 and 2004 (Figure S5). Melt rates of Amery Ice Shelf, spatially averaged for deep ice drafts, varied from near 0 to 6.5 m yr−1 with particularly high values between 2003 and 2007. We speculate that this maximum could be associated with a continuous drainage of a ~0.8 km3 subglacial lake under Lambert Glacier between 2003 and 200641; subglacial discharge is known to drive energetic plumes42,43 that increase basal melt rates near grounding lines.

For Amundsen Sea ice shelves, melt rates showed substantial variability, with the highest sustained rates occurring in the late 2000s (Figure 4e). Variability in Mode 2 melting of Amundsen Sea ice shelves has been previously identified in ocean observations and linked to variability in the tropical Pacific at both interannual44,45 and decadal4 time scales. The magnitude of our estimates of variability in melt rates of Dotson Ice Shelf (around 60 Gt/yr peak to trough) agrees with the variability in independent estimates of meltwater flux from repeated oceanographic sections along the ice-shelf front4 (Figure S6) but is larger than the variability expected from an ocean model that used atmospheric forcing from the same period46. Excess basal melting and changes in ice shelf extent (Figure S8, Table S1) in the Amundsen Sea sector between 1994 and 2018 could be due to a longer-term increase in the thickness of CDW incursions under ice shelf cavities associated with atmospheric and oceanic responses to anthropogenic forcing47.

Our new estimates of time-varying melt rates permit assessment of whether ocean circulation models can represent the complex feedbacks between water mass production and conversion processes acting under the ice shelves and over the continental shelves north of the ice fronts. The large temporal variability of melting in all three modes (Figure 4) will contribute to changes in the distribution of different water masses over the Antarctic continental shelf seas and into the global ocean. The ISW produced through Mode 1 melting contributes to the formation of particularly cold, dense forms of AABW26,48,49. Changes in Mode 2 and Mode 3 melting modify the fluxes of meltwater into the upper ocean in adjacent coastal regions15,34. Increased ocean stratification from shallow sources of cold, buoyant water alters the seasonal cycle of sea ice50 and decreases the potential for deep convection that drives production of Dense Shelf Water types including HSSW. Changes in relative strengths of these melt modes modify the geostrophic ocean circulation over the Antarctic continental shelf seas, feeding back into the transport of ocean heat between coastal sectors and into the sub-ice-shelf cavities7.

We have produced two new datasets of basal melt rates for nearly all of Antarctica’s ice shelves. One dataset provides melt rates at high spatial resolution (500 m grid) for most ice shelf areas, averaged over the period 2010–2018. The second dataset allows for the evaluation of annual estimates of basal melt rates at lower spatial resolution (>10 km) for the period 1994–2018. Together, these datasets reveal large variability in total meltwater fluxes from individual Antarctic ice shelves, with distinct, regionally variable, signatures of temporal variability for different modes of ocean-driven melting. Our data can be used to better isolate the glaciological and climate drivers of processes that modulate current ice sheet mass loss and provide improved metrics for calibration and validation of melt rates used in both ice-ocean and Earth-system models.

Methods

Melt rates from Lagrangian CryoSat-2 analysis, 2010–2018

In a Lagrangian reference frame (following a parcel of ice), and assuming that the ice shelf is floating in hydrostatic balance, the net ice shelf height change observed using satellite altimetry , where h is the ice shelf surface height relative to the height of the ocean surface

Height of the ocean surface

We estimated the height of ocean surface

Lagrangian height changes

We derived

Thickness change due to ice shelf divergence ( H i ∇ ⋅ v )

We estimated the

Surface mass balance (M s ( d h a i r / d t )

For the

Steady-state basal melt rates

We estimated the “steady-state” basal melt rate,

Depth-dependence of area-integrated meltwater fluxes

We estimated the ice shelf draft,

Ocean thermal forcing

We define thermal forcing,

Time series of height change from Eulerian ERS-1, ERS-2, Envisat, and CryoSat-2 analysis

In addition to 2010–2018 mean values of

Estimating altimeter-derived height changes

We obtained ERS-1, ERS-2, and Envisat height data (

We first derived height changes for each mission separately. For each grid cell, we estimated height changes for each mission if there were at least 15 data points spanning at least 3 years using:

The height-change rate (

We processed CryoSat-2 data using the Eulerian ‘plane-fit’ technique described in ref. 61 (their Section S1) after applying the same geophysical corrections used for ERS-1, ERS-2, and Envisat data.

Merging of altimeter time series

To avoid biases from different spatial sampling, we discarded data from all grid cells which did not contain height change measurements from all four missions. For grid cells where sufficient data were available, we then merged the height change time series from the four radar altimeters by ensuring that height-change rate during the time periods with overlapping data was equal to the average of the height-change rates estimated from each altimeter. Therefore, we imposed

Influence of surface melting on radar-derived height changes

We found large decreases in RA-derived height changes between 1992 and 1994 across Antarctica. In some previous studies2,76, data from this period were excluded due to this anomalous signal. Using surface melt data from RACMO and a positive degree day model based on MERRA-264, we found that this change in RA-derived height change was primarily due to a large circum-Antarctic surface melt event in December 1991. This melt event likely created a bright radar reflector, and its burial following subsequent snowfall was tracked by the radar altimeter, which caused a downward trend in estimated height. Due to the large effect of this event across several ice shelves around Antarctica, we excluded this period in our analysis.

For Ross Ice Shelf, we found large changes in height following anomalous surface melt events during the austral summers of 1991/1992, 2002–2003, and 2015/2016. Two of these (1991/1992 and 2015/2016) were the largest surface melt events over the ice shelf during the 1980–2016 period77. We accounted for the radar response following such events by estimating a time series of

Time series of melt rates

From the merged multi-mission Eulerian height-change rate time series

Uncertainty estimation

We compared GSFC-FDMv0 estimates of

We estimated uncertainties for all terms in Equation S5 as the uncertainties from the linear regression, and propagated these to

Estimates of marine ice thickness

We estimated thickness of marine ice (

Changes in iceberg calving rates

We have so far only considered temporal variability in ice shelf mass and meltwater flux due to changes in ice shelf basal melt rates relative to steady-state values. However, ice shelf hydrofracture in the Antarctic Peninsula86 and excess iceberg calving rates due to long-term dynamic thinning of Amundsen Sea87 have also contributed to net ice shelf mass loss and increases in meltwater export to the upper ocean in recent decades. We estimated net mass loss due to changes in ice shelf extent from ice shelf thickness estimates generated using elevations from the ERS-1 geodetic phase (1994–1995) for regions where ice shelf areas decreased; these were excluded from previous thickness estimates88. We estimated a net mass loss of 1650±200 Gt from Antarctic Peninsula ice shelves during our record (Figure S7) due to the hydrofracture-induced collapse of Larsen A, Larsen B, and sections of Wilkins ice shelves89,90. Additionally, net retreat of Thwaites, Pine Island, and Getz ice shelves in the Amundsen Sea contributed to a combined net mass loss of 1230±70 Gt. The combined mass loss from excess calving of Antarctic Peninsula and Amundsen Sea sector ice shelves was 2880±210 Gt, which is comparable to our circum-Antarctic mass loss estimate of 3960±1100 Gt from thinning ice shelves (Figure 3a).

Acknowledgements:

This study was funded by NASA grants NNX17AI03G and NNX17AG63G. SA was also supported by the NASA Earth and Space Science Fellowship. We thank the two anonymous reviewers, members of the Scripps Polar Center, Susan Howard, and Keith Nicholls for their important contributions to this manuscript.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

References only in Methods

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

Floating objects

Basal melt rates of Antarctic ice shelves using CryoSat-2 altimetry.

Rates are averaged over 2010–2018 and shown at 500 m posting. The units are m of ice equivalent, assuming an ice density of 917 kg/m3. The thermal forcing, defined as the temperature above the in situ freezing point of seawater, is mapped for water depths <1500 m. For water depths less than 200 m the seafloor thermal forcing is shown, and for water depths >200 m, the maximum thermal forcing between 200 m and 800 m is shown (Methods Section S2).

Vertical structure of melting and refreezing rates for selected ice shelves.

Depth-dependence of area-integrated meltwater flux (2010–2018) per m of ice shelf draft (depth of the ice shelf base below sea level) for six major ice shelves (locations shown in Figure 1). The scale for the horizontal axis is shown by the solid black line within the figure. The shaded regions in red and blue represent the mean values, and the dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals. The purple lines are hypothetical steady-state meltwater fluxes (i.e., the meltwater fluxes required to maintain constant ice shelf mass). Warm-water ice shelves are distinguished from cold-water ice shelves by their higher average rates of meltwater production driven by intrusions of warm Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW) or modified CDW into the ice shelf cavity.

Variations in Antarctic ice shelf mass between 1994 and 2018.

(a) Cumulative ice shelf mass change between 1994 and 2018 for the Pacific (red), Atlantic (blue), and Indian (orange) ocean sectors of Antarctica, with shading showing 95% confidence intervals. The region definitions are shown on the map, and the combined total for all ice shelves is shown in black. (b) Meltwater fluxes for 1994–2018 from ocean-driven ice shelf basal melting for the same regions. Dashed lines represent meltwater fluxes in steady-state, where the mass of the ice shelves is constant through time. Total meltwater flux estimates for the ICESat era are averaged between two studies19,20.

Time-dependent basal melt rates for different modes of melting.

(a-d) Area-averaged basal melt rates for selected regions within the four largest Antarctic ice shelves. Regions shown in red experience melting predominantly from cold, High Salinity Shelf Water inflows at deep ice drafts (Mode 1), while regions shown in blue typically experience melting from intrusions of Antarctic Surface Water at shallow ice drafts (Mode 3). (e) Basal melt rates for Amundsen Sea ice shelves, which experience melting from inflows of warm Circumpolar Deep Water (Mode 2). Gaps in the spatial coverage reflect the sampling of the altimeters prior to CryoSat-2.

Interannual variations in meltwater input to the Southern Ocean from Antarctic ice shelves

Interannual variations in meltwater input to the Southern Ocean from Antarctic ice shelves