Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

Binary Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) is the most common method used by researchers to analyze clustered binary data in biological and social sciences. The traditional approach to GLMMs causes substantial bias in estimates due to steady shape of logistic and normal distribution assumptions thereby resulting into wrong and misleading decisions. This study brings forward an approach governed by skew generalized t distributions that belong to a class of potentially skewed and heavy tailed distributions. Interestingly, both the traditional logistic and probit mixed models, as well as other available methods can be utilized within the skew generalized t-link model (SGTLM) frame. We have taken advantage of the Expectation-Maximization algorithm accelerated via parameter-expansion for model fitting. We evaluated the performance of this approach to GLMMs through a simulation experiment by varying sample size and data distribution. Our findings indicated that the proposed methodology outperforms competing approaches in estimating population parameters and predicting random effects, when the traditional link and normality assumptions are violated. In addition, empirical standard errors and information criteria proved useful for detecting spurious skewness and avoiding complex models for probit data. An application with respiratory infection data points out to the superiority of the SGTLM which turns to be the most adequate model. In future, studies should focus on integrating the demonstrated flexibility in other generalized linear mixed models to enhance robust modeling.

Introduction

Binary outcomes are prominent in many applied sciences, including but not limited to biological and social sciences. Moreover, in cross sectional as well as panel studies, dichotomous responses are often naturally grouped by sampling techniques or some properties of the sampling units [1]. The preferred modern method to analyze clustered binary data is through the Generalized Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) framework [2]. Indeed, when a binary outcome has been recorded repeatedly or in the presence of latent factors, GLMMs allow accounting explicitly for over-dispersion and correlation within clusters using random effects.

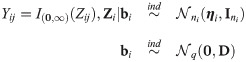

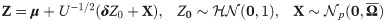

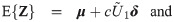

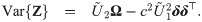

Let Yij denote the binary outcome (0 or 1) of the jth measurement (j = 1, 2, ⋯, ni) and Yi the collection of responses from the ith cluster, i.e. , i = 1, 2, ⋯, n. In terms of an underlying latent continuous random vector

The link function indeed has a critical role in GLMMs since it heavily impacts estimates, predictions and consequently interpretations [4, 6]. As a result, in the binary generalized linear model literature, aside the logistic and probit models based on the steady shape logistic and normal distributions respectively, there has been increasing efforts to render the link function flexible. Many works have considered heavy tailed link functions, for instance the Semi-Nonparametric [7], Student-t [8] and generalized t [9] distributions, and elliptical scale mixtures [10, 11]. Indeed, the maximum likelihood estimators of logistic and probit regression models are not robust to outliers [7]. Heavy tailed links are not sensitive to outliers and thus allow outlier-robust inference. In particular, the links functions based on the Student t distribution incorporate observation-specific stochastic weights which can be used for outlier detection [7, 12]. Similarly, skew-probit [13], skew generalized t [9], asymmetric logistic [14], loglog and complementary loglog, power symmetric and reciprocal power symmetric [15] links were used among others to handle situations where the probability of a given binary response approaches zero at a different rate than it approaches one. Skew logistic distributions have also been developed (see e.g. [16]) and may be used with the same aim in mind. For example [9], discussed a prostate cancer study where the outcome variable Y represents the presence or the penetration of cancer in or near the prostate capsule of patients. The rate at which the probability of “Y = 1” approaches one is expected to be very different (slower) from the rate at which it approaches zero [9]. For this study, the skew generalized t-link fits best the data [9], indicating that the simultaneous use of skewed and heavy tailed link functions can lead to more effective modelling of binary data.

Furthermore, although random effects are traditionally assumed to be normally distributed in GLMMs, this may not be realistic [17, 18]. Therefore, huge efforts have been devoted to making the random effects distribution in GLMMs flexible, replacing the normal distribution with, for instance Semi-Nonparametric [19], probability integral transformation of normal [20], skew normal [21], log-normal [22, 23], Student-t [24] and scale mixtures of normal [25] distributions.

The above background demonstrates the extent to which the number of possible approaches for fitting a flexible GLMM to correlated binary outcomes goes, although none of these approaches attempts to explicitly account for skewness and tail behavior of the link function as well as the random effects distribution simultaneously. However, the misspecification of the link function or the random effects distribution can introduce substantial bias and reduce the accuracy of the mean response as well as heterogeneity estimates [6, 18]. Standing in a fully parametric frame, we propose a unifying approach based on skew generalized t (SGT) distributions [26], that is the class of models including among others the normal, the skew normal and the Student t models. The use of a skew generalized t family instead of the Student t family allows to rescale fixed effects so that they have the same interpretation as in the mixed probit model in Eq (1).

Our contributions include i) an extension of the flexible generalized t-link model built for independent binary samples proposed by [9] to deal with dependent binary samples (mixed model); ii) a parameter-expanded EM algorithm [27] for computing the maximum likelihood of skew generalized t-link models for correlated binary data, extending the EM algorithm of [24] for t-link models; and iii) empirical Bayes estimators of skew t distributed random effects in mixed models for binary data.

The organization of the paper is as follows. Section 2 presents preliminary results on the SGT distributions and the truncated SGT distributions and their first two moments. Section 3 specifies the SGT-link model (SGTLM) and describes maximum likelihood estimation and cluster-specific inference based on random effects and weights. A simulation study assessing the relative performance of the SGTLM relative to existing methods and the application of the modelling approach to a real respiratory infection data are presented in Section 4. Concluding remarks are given in section 5.

Preliminary results

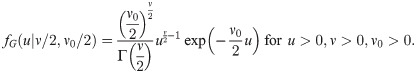

In this section, we present some useful properties of the skew generalized t distributions.

Multivariate skew generalized t distributions

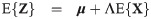

Multivariate skew generalized t (SGT) distributions are special cases of multivariate skew scale mixture of normal (SSMN) distributions [28] (pages 102-103) which we first introduce. A random variable Z is said to follow a p−variate SSMN distribution with location μ, scale Ω, and shape λ, if it can be represented as [29] (page 20, Eq 3.12):

Lemma 1 (see

S1 Appendix

for a proof)

The free parameters (μ, δ, Ω

and

ν) of a SSMN distribution with the representation in

Eq (2)

are identifiable if and only if i) the scale mixing distribution FU(⋅|ν) is identifiable and ii)

FU(⋅|ν) does not satisfy

On setting

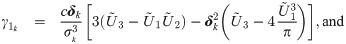

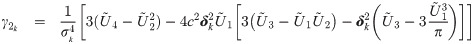

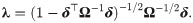

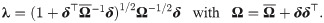

We notice from the expressions for skewness Eq (5) and kutosis Eq (6) indices that the parameter λ controls the shape of the distribution only through the working shape parameter δ = (1 + λ⊤

λ)−1/2

Ω1/2

λ. This quantity is invariant under marginalization, i.e. by the stochastic representation in Eq (2), for any arbitrary subset of Z, the working shape parameter is the corresponding subset of δ. It is worth noticing however that the quantity δ cannot be specified unrestrictedly, independently of Ω. Indeed, we observe that δ = (1 + λ⊤

λ)−1/2

Ω1/2

λ implies that λ = (1 + λ⊤

λ)1/2

Ω−1/2

δ. This in turn gives λ⊤

λ = (1 + λ⊤

λ)δ⊤

Ω−1

δ which yields λ⊤

λ(1−δ⊤

Ω−1

δ) = δ⊤

Ω−1

δ. We then get

Lemma 2 (see

S2 Appendix

for a proof)

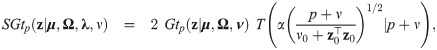

Let us consider the SGT distribution

SGtp(z|μ, Ω, λ, ν) = Stp(z|μ, Ω*, λ, ν);

If

Lemma 2 indicates that any SGT vector is a rescaled version of a ST vector. However, in the frame of binary data models, the use of a SGT distribution instead of a simple ST distribution as link function allows to control the scale of the link function through the parameter ν0 [9]. Specifically, a skew generalized t-link allows to define a skewed and heavy-tailled binary mixed model where fixed effects have the same scale and interpretation as in the mixed probit model in Eq (1). Interestingly, the popular logit and probit links for binary data can be recast as special cases of the cdf of the SGT class of distributions. Indeed, the normal distribution is a limiting case of SGT distributions when ν0 = ν → ∞ and λ = 0. Moreover, the logistic distribution is well appoximated by a rescaled Student t distribution with appropriate degrees of freedom [8] (page 228). These constatations make the SGT distributions appropriate for extending the traditional probit and logistic GLMMs, accounting for skewness and heavy tail behaviors. To this end, we present in the next section some results on truncated multivariate SGT distributions since binary data can reflect truncation of latent continuous variables.

Truncated multivariate skew generalized t distributions

As seen for the mixed probit model in Eq (1), models for binary data can be defined by truncating latent variables following continuous distributions. We define in this section a class of truncated multivariate skew generalized t distributions which are useful for a latent variable representation of skew generalized t-link binary data models. We also give expressions to evaluate some joint moments of a truncated multivariate skew generalized t distribution and a gamma distribution, as they prove useful in the implementation of the EM algorithm for the skew generalized t-link model.

Let

In the frame of correlated binary data models, the truncation region

We shall use the simplified notation

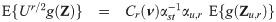

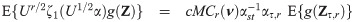

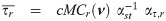

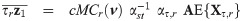

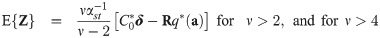

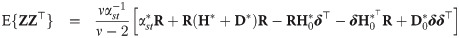

The implementation of an EM algorithm for a SGT distribution based binary data model requires joint moments of the form

Proposition 1 (see

S3 Appendix

for a proof)

Let

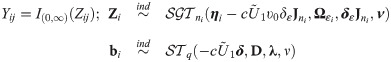

By the mean of a simple linear transformation, we obtain from Proposition 1 the joint expectations

Corollary 1 (see

S4 Appendix

for a proof)

Let

For a practical use of Corollary 1, the cumulative multivariate skew t distribution is required. To this end, the function pmst of the package sn [35] in R freeware [36] is an appropriate routine.

Moments of truncated multivariate skew generalized t distributions

The evaluation of expectations

Let

Proposition 2 (see

S5 Appendix

for a proof)

Let

The following corollary gives the first two moments of a general right truncated SGT vector

Corollary 2

Let

When ν → ∞, the truncated multivariate SGT family has the truncated multivariate skew normal family as a limiting case (see S5 Appendix for a definition and formulas for computing the first two moments).

Skew generalized t-link mixed binomial model

This section defines the skew generalized t-link model (SGTLM) and describes an Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm [39] accelerated using parameter expansion [27] for likelihood inference. Empirical Bayes estimators of random effects and weights are also obtained for cluster specific inference.

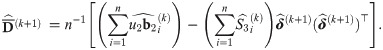

Model specification and marginal log-likelihood

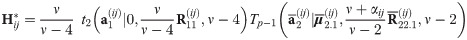

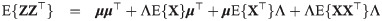

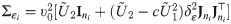

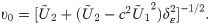

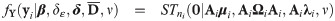

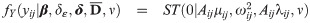

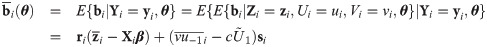

The skew generalized t-link GLMM (SGTLM) considered in this work is defined as:

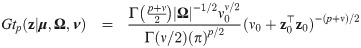

In the SGTLM, the distribution of a single latent outcome Zij is

The positive constant υ0 in the SGTLM controls the scale of the latent variable Zij and thus the scale of the model link function. Indeed, from Eq (28), the conditional variance of Zij is

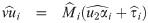

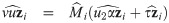

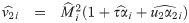

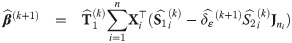

By Eq (2), the SGTLM has the stochastic representation

Proposition 3 (see

S6 Appendix

for a proof). Let us consider the latent vector

Zi

and the binary variable Yij

in

Eq (27)

and define

Eq (32) conveniently expresses for a value yi of Yi, the likelihood as a cumulative probability of a ST distribution whose location, scale and shape parameters depend on yi, using the identities P(Zij > zij) = P(−Zij < −zij) and sign(Zij) = 2Yij − 1 where sign(⋅) returns the sign of its argument. On using Eq (4) on the distribution of Zi given in Proposition 3, the variance-covariance matrix of the outcomes at the latent scale is

The parameters of the SGTLM include β, δε, δ,

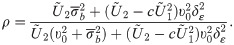

Model identifiability

Estimations in the skew generalized t-link model (SGTLM) may produce inconsistent results which would induce unreliable and misleading conclusions, if the model is not identifiable. It is thus of great importance to check whether different points in the parameter space can be distinguished from observations yi. We analyse in this section the identifiability of the SGTLM and indicate when it is necessary to restrict the parameter space to ensure reliable inference from observed data. We restrict attention to the case υ0 = 1 (ignoring Eq (29)) since υ0 is an artificial device only included to ensure a unit variance in the conditional link function as in the traditional probit mixed model.

Although not sufficient, the identifiability of the SGTLM requires both the marginal random effects distribution and the conditional model given random effects to be identifiable. The identifiability of the random effects distribution follows from the identifiability of multivariate skew t distributions. We survey the identifiability of the conditional model before turning to the marginal model.

• Conditional identifiability

Conditional on the random effects bi and for fixed degrees of freedom parameter ν, the identifiability of the SGTLM reduces to the identifiability of the fixed effects skew-probit model. This follows because the skew t inverse link function is an average of the skew-probit inverse link function with respect to the gamma mixing distribution. The identifiability of the skew-probit model with one covariate has been recently shown to depend on the nature (binary/continuous) of the covariate in the model [42]. Indeed, the fixed effect skew-probit model is not identifiable in the absence of any covariate (i.e. each Xi is a column of ni ones) [42] (page 1624, Proposition 2.1) or in the presence of a binary covariate [42] (page 1626, Proposition 2.2). On the other hand, the fixed effect skew-probit model is identifiable when the covariate is continuous [42] (page 1627, Proposition 2.3). Extension to the case of multiple covariates is straightforwardly obtained by requiring the covariate matrix

• Marginal identifiability

From Proposition 3, it appears that when υ0 = 1 the paramaters δε and δ enter the marginal distribution of Yi only through the marginal working shape

Fortunately, the non identifiability of the skewness of conditional link function and random intercept does not affect the success probability of the response since this only depends on Δi, but not on the individual values of δϵ and δ0. However, since the conditional link scale depends on δϵ through υ0, the confounding problem affects the scale and thus the interpretation of fixed effects. Moreover, inference on the random intercept is affected since the random intercept variance and skewness depend on δ0. For example, δϵ + δ0 = 0 only indicates null marginal skewness, and in no way absence of link function and random intercept skewness which could be equally strong but of opposite signs. Thus, only a lower bound can be given to the random intercept variance:

In the very common situation where the mixed model includes a random intercept term, prior information on the shape of the link function and/or the random intercept is required to place a meaningful restriction on the parameter space by setting for instance δϵ = 0 or δ0 = 0 or δϵ = δ0. In the absence of such information, we advocate to consider the restriction δ0 = 0 because the success probability of a response may exibit skewness, irrespective of the presence of random effects. This restriction thus allows to recover a fixed effects skew generalized t-link model when no random effect is considered. Overall, the restriction δ0 = 0 simply expresses the unability of the SGTLM to capture any additional skewness structure from the data through the inclusion of only random intercept. For completeness, we develop in the next section an estimation procedure for the full model in Eq (27), since the introduction of any equality restriction on δϵ and δ0 can be straightforwardly reduced to δ0 = 0.

The two restrictions discussed in this section are related to the structure of the quantity Δi and are required only for some specific data structures (models including a binary covariate or models with a random intercept only). However, even when a restriction is required on δε or the first element of δ, the quantity Δi itself can remain unrestricted. When a restriction is required, it forces the skewness from a data to be summarized either by δε or elements of δ. Overall, the SGT-link function is always allowed to be skewed (unconditional link). But some designs do not allow to distinguish skewness in the conditional link function from skewness in the distribution of random effects.

Maximum likelihood inference

Estimation via the EM algorithm

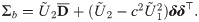

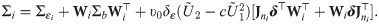

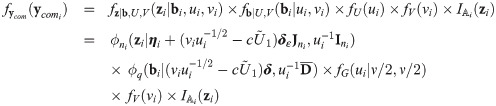

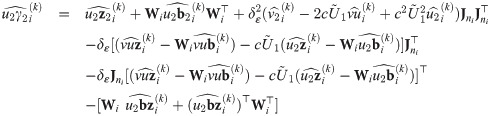

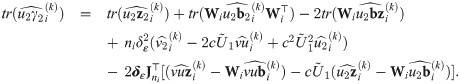

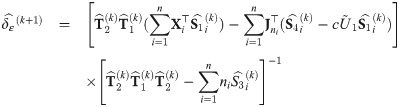

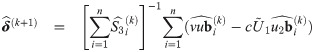

The choice of the value of υ0 in Eq (29) is in line with one of our purposes: rescale fixed effects so that they have the same interpretation as in the mixed probit model. There is no need to define υ0 depending on situations, because in our proposal, υ0 is fixed. However, since υ0 is simply a scaling factor, it may be given any positive value during estimation, as long as the estimates are rescaled after the convergence of the estimation procedure so that υ0 is finally given by Eq (29). Indeed, because routines are basically written for the skew t distributions, we used υ0 = 1 in the EM algorithm and rescaled the estimates at the end of the procedure. Let us consider the complete data

Proposition 4 (see

S7 Appendix

for a proof). Consider the random variables Yij, Zi, bi, Ui, and Vi

as defined in

Eq (27)

with υ0 = 1, and an update

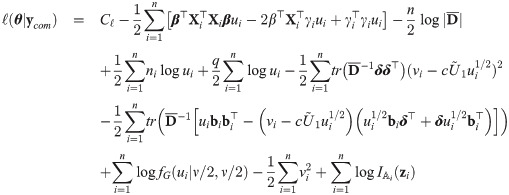

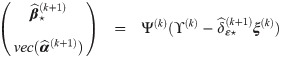

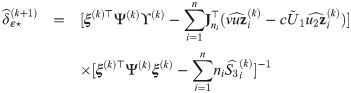

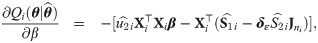

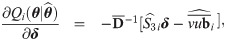

The M-step jointly maximizes

Proposition 5 (see

S8 Appendix

for a proof)

Consider an identifiable SGTLM as defined in

Eq (27)

with υ0 = 1; and an estimate

At convergence of the EM algorithm, we obtain the estimate

It is worthwhile noticing however that the inclusion of a profiled marginal log-likelihood maximization step would prevent the convergence of the whole estimation procedure if the marginal log-likelihood in Eq (36) as a function of ν is unbounded for a particular dataset. This issue especially when ν is close to zero. Another challenge associated to the estimation of ν is time. The use of this strategy requires a very fast routine to compute cumulative probabilities of the skew t distributions. As an alternative route to estimate ν, we point out the model selection approach of [51] (page 893). It consists in setting a grid of feasible values of ν and obtaining a sequence of estimates

Accelerating EM via parameter-expansion

Besides its attractiveness and stability for handling incomplete data models, the EM algorithm sometimes experiences slow convergence, which has motivated many methods to accelerate its linear convergence speed. Among popular EM accelerators, the so-called parameter-expanded (PX) EM algorithm was proposed by [27] to speed up convergence. Let us consider a complete data model F(ycom|θ). The PX-EM algorithm expands F(ycom|θ) to a larger model FX(ycom|Θ) parameterized by

Summary of the estimation procedure

The estimation procedure starts with a parameter

E-step: compute conditional expectations defined by Eqs (40)–(46) with

PX M-step: obtain

Test: compute λmax the dominant eigen value of

E-step: compute conditional expectations defined by Eqs (40)–(46) with

Test: compute the marginal likelihood

Rescaling: compute υ0 using (29) and rescale the estimates as

Approximate standard errors

With a view to allow asymptotic inference in SGTLM, we follow the empirical information-based method of [52] (pages 132-133) to compute the asymptotic variance-covariance matrix of the ML estimate

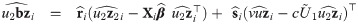

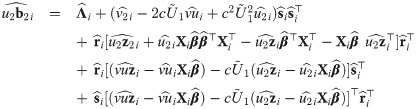

Empirical Bayes estimators of random effects and weights

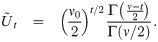

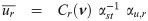

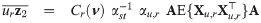

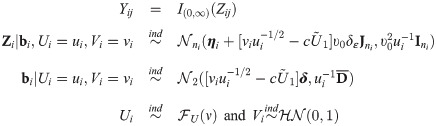

In this section, we provide the empirical Bayes estimators of cluster specific random effects and weights that are useful for evaluating individual intercepts and slopes as well as detecting outlying individuals. From Eq (27), the distribution of bi conditional on Zi = zi, Ui = ui and Vi = vi is multivariate normal with mean

For outlying individuals detection, individual weights Ui are predicted by

Applications

This section presents a simulation study for assessing performance of SGTLM, and an application of the modeling approach to a real dataset.

Simulation study

We conducted a simulation to evaluate the proposed approach to the analysis of correlated binary data. The simulation experiment targeted four specific objectives. First, it assessed for different sample sizes, the abilities of the probit (PM), the skew-probit (SPM), the generalized t-link (GTLM) and the skew generalized t-link (SGTLM) models to recover population parameters when the common normality assumption for the link function is either violated or not. The widely used logistic model was not investigated as the logistic distribution can be considered as a special case of the Student t distribution [8] hence the logistic model is a special case of GTLM. Second, the experiment evaluated the extent to which asymptotic 95% confidence intervals (CI95%) can detect the presence of spurious skewness. Third, the experiment evaluated the ability of empirical Bayes estimators of random effects to predict true random effects. Finally, the simulation study assessed the ability of Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), Schwarz’s Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Hannan-Quinn criterion (HQ) to select the correct model fit. All computations were performed in R.

Simulation design

Mimicking the structure of the simulation model studied in [24] (page 1116), we considered the following GLMM:

Under this general class of SSMN latent models, we considered two data models. The first is the probit data model where U = 1, δ1 = 0 and δε = 0 (probit link, υ0 = 1). The second is the skew generalized t-link data model with δε = −2 and δ1 = 2 and

Performance measures

In addition to estimates of fixed effects (

| Measure | Formula | Role |

|---|---|---|

|  | Unbiasedness of  |

|  | Accuracy of  |

|  | Unbiasedness of  |

|  | Accuracy of  |

|  | Precision of  |

|  | Reliability of estimated SE |

|  | Coverage probability of  |

|  | Coverage probability of  |

|  | Predictive power |

|  | Model selection |

|  | Model selection |

|  | Model selection |

Notes: SE = standard error,

Simulation results

Simulation results presented in Tables 2 and 3 show that under the probit data generation mechanism, the probit, the skew-probit, the generalized t (GT)-link and the skew generalized t (SGT)-link models recovered the population parameter values. Indeed, the percentage of bias was below 5% at all levels for fixed effects, whereas for variance components, the percentage of bias was below 20%. We particularly noticed a high relative bias in the variance component (%Bias = 17.33) under probit fit to probit data (assuming the true model) with small sample size (n = 100). This may be explained by the maximum likelihood estimation method which is known for providing biased variance components [56]. Nevertheless, this can be improved by opting for residual maximum likelihood estimation procedure [56]. However, it is worth noticing that the estimation improves as the sample size increases and the empirical standard error estimates agree with the standard deviations from the simulations. The results for n = 100 and n = 500 are consistent with findings in [24] where empirical information based standard errors approached Monte Carlo standard errors. Moreover, the 95% confidence interval for the skewness parameters allows to detect spurious skewness in the skew-probit and the SGT-link models with coverage probabilities of 100%. This result can be explained by the underlined high accuracy of information based standard errors in this type of model. The power in predicting random effects varied from R2 = 0.45 to R2 = 0.47 for random intercepts and from R2 = 0.23 to R2 = 0.28 for random slopes, but was comparable for the three fitting models. Finally, it appears that on average all model selection criteria correctly considered probit fitting model as the parsimonious model.

| Parameters | Measures | n = 100 | n = 500 | n = 1000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probit | Skew probit | Probit | Skew probit | Probit | Skew probit | ||

| β0(−1) | Mean | -1.04 (0.25) | -1.03 (0.30) | -1.01 (0.12) | -1.04 (0.31) | -1.00 (0.08) | -1.00 (0.11) |

| %Bias | -3.61 | -3.01 | -0.64 | -4.03 | -0.32 | -0.23 | |

| 0.25 [0.23] | 0.27 [0.26] | 0.11 [0.12] | 0.29 [0.24] | 0.08 [0.08] | 0.09 [0.11] | |

| CP | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| β1(1) | Mean | 1.03 (0.24) | 1.02 (0.41) | 1.01 (0.10) | 1.00 (0.41) | 1.00 (0.07) | 1.00 (0.42) |

| %Bias | 3.21 | 1.96 | 0.59 | 0.46 | 0.13 | 0.16 | |

| 0.23 [0.22] | 0.43 [0.43] | 0.1 [0.10] | 0.48 [0.47] | 0.07 [0.07] | 0.08 [0.07] | |

| CP | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| Mean | 0.54 (0.24) | 0.51 (0.29) | 0.51 (0.09) | 0.53 (0.29) | 0.50 (0.06) | 0.51 (0.07) |

| %Bias | 7.98 | 2.24 | 1.39 | 2.35 | 0.12 | 1.06 | |

| σ12(0.25) | Mean | 0.30 (0.34) | 0.23 (0.48) | 0.25 (0.13) | 0.22 (0.48) | 0.25 (0.09) | 0.24 (0.49) |

| %Bias | 18.48 | -6.52 | 1.84 | -12.02 | 1.55 | -2.02 | |

| Mean | 1.17 (0.91) | 1.10 (0.95) | 1.02 (0.34) | 1.11 (0.94) | 1.02 (0.22) | 1.00 (0.47) |

| %Bias | 17.33 | 9.94 | 2.42 | 10.98 | 1.96 | 0.99 | |

| δε(0) | Mean | - | 0.02 (0.65) | - | 0.02 (0.46) | - | 0.00 (0.46) |

| - | 0.61 [0.62] | - | 0.71 [0.51] | - | 0.61 [0.46] | |

| CP | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| δ1(0) | Mean | - | -0.02 (0.37) | - | -0.02 (0.38) | - | -0.00 (0.25) |

| - | 2.00 [1.84] | - | 2.00 [1.72] | - | 2.00 [0.22] | |

| CP | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| Mean | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Mean | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| AIC | Mean | 548.29 | 552.14 | 3732.11 | 3733.80 | 7522.50 | 7524.04 |

| BIC | Mean | 570.27 | 582.92 | 3762.14 | 3775.85 | 7556.00 | 7570.94 |

| HQ | Mean | 556.85 | 564.12 | 3742.91 | 3748.92 | 7534.13 | 7540.33 |

Mean value and root mean square error (in parentheses), percentage of bias (%Bias), mean standard error (SE) and sample standard deviation (in square brackets), coverage probability (CP) of estimates, coefficient of determination (R2) and averages of AIC, BIC and HQ criteria for sample sizes (n) of 100, 500 and 1000.

Notes: In the first column (Parameters), model parameters are followed in parentheses by their respective true values;—means “not applicable”; the coverage probability (CP) is the probability that an approximate confidence interval (assuming asymptotic normality for the model parameter) contains the true parameter value.

| Parameters | Measures | n = 100 | n = 500 | n = 1000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT-link | SGT-link | GT-link | SGT-link | GT-link | SGT-link | ||

| β0(−1) | Mean | -1.05 (0.26) | -1.05 (0.24) | -1.01 (0.11) | -1.03 (0.11) | -.1.00 (0.10) | -1.00 (0.08) |

| %Bias | -4.95 | -4.61 | -1.06 | -2.94 | -0.17 | -0.17 | |

| 0.25 [0.24] | 0.27 [0.25] | 0.15 [0.12] | 0.11 [0.12] | 0.08 [0.08] | 0.06 [0.05] | |

| CP | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| β1(1) | Mean | 1.03 (0.32) | 1.03 (0.23) | 1.01 (0.14) | 1.03 (0.10) | 1.00 (0.12) | 1.00 (0.07) |

| %Bias | 3.16 | 3.28 | 1.62 | 2.90 | 0.08 | 0.13 | |

| 0.23 [0.20] | 0.25 [0.22] | 0.13 [0.13] | 0.1 [0.10] | 0.07 [0.07] | 0.07 [0.07] | |

| CP | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | |

| Mean | 0.47 (0.12) | 0.47 (0.10) | 0.49 (0.11) | 0.50 (0.09) | 0.50 (0.05) | 0.50 (0.03) |

| %Bias | -5.36 | -5.57 | -1.76 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.12 | |

| σ12(0.25) | Mean | 0.26 (0.53) | 0.24 (0.40) | 0.24 (0.22) | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.19) | 0.25 (0.02) |

| %Bias | 4.00 | -4.82 | -3.96 | -6.26 | -1.68 | 1.55 | |

| Mean | 1.09 (.62) | 0.99 (0.49) | 1.00 (0.18) | 0.99 (0.12) | 0.99 (0.11) | 0.99 (0.12) |

| %Bias | 8.98 | -1.12 | -0.78 | -1.13 | -0.87 | -0.91 | |

| δε(0) | Mean | - | 0.00 (0.56) | - | 0.01 (0.54) | - | 0.00 (0.41) |

| - | 0.44 [0.56] | - | 0.46 [0.56] | - | 0.48 [0.44] | |

| CP | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| δ1(0) | Mean | - | 0.00 (0.18) | - | 0.00 [0.14] | - | 0.00 [0.14] |

| - | 1.22 [0.18] | - | 0.99 [0.16] | - | 0.62 [0.17] | |

| CP | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| Mean | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Mean | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.28 |

| AIC | Mean | 552.09 | 554.37 | 3733.10 | 3736.21 | 7523.12 | 7525.21 |

| BIC | Mean | 581.43 | 589.55 | 3762.43 | 3784.26 | 7568.95 | 7573.26 |

| HQ | Mean | 561.97 | 568.06 | 3744.11 | 3764.90 | 7538.91 | 7542.49 |

Mean value and root mean square error (in parentheses), percentage of bias (%Bias), mean standard error (SE) and sample standard deviation (in square brackets), coverage probability (CP) of estimates, coefficient of determination (R2) and averages of AIC, BIC and HQ criteria for sample sizes (n) of 100, 500 and 1000.

Notes: In the first column (Parameters), model parameters are followed in parentheses by their respective true values;—means “not applicable”; the coverage probability (CP) is the probability that an approximate confidence interval (assuming asymptotic normality for the model parameter) contains the true parameter value.

Under a SGT-link data generation mechanism, the probit model performed poorly, showing large relative fixed effects bias values which decreased from 46% for samples of size n = 100 to 18% for samples of size n = 1000 (Table 4). The SGT-link model estimates were the less biased (%Bias < 12) as well as the most accurate with the lowest root mean square errors across all levels (Table 5). The same observations apply to variance components which were highly biased downward for probit, skew-probit and GT-link models (%Bias up to 90) relative to the SGT-link model (%Bias < 7). Regarding estimates of skewness parameters, the coverage probability was low (53% to 94%) for small sample size (n = 100) and approached nominal (95%) value for larger sample sizes (n = 500, 1000). The skew-probit model estimates (coverage probability down to 53%) were less reliable than estimates from the SGT-link model (coverage probability above 90%).

| Parameters | Measures | n = 100 | n = 500 | n = 1000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probit | Skew probit | Probit | Skew probit | Probit | Skew probit | ||

| β0(−1) | Mean | -1.46 (1.53) | -1.33 (1.30) | -1.28 (1.29) | -1.28 (1.31) | -1.18 (1.27) | -1.22 (0.92) |

| %Bias | -46.18 | -33.41 | -28.30 | -28.13 | -18.27 | -22.08 | |

| 0.95 [0.99] | 0.89 [0.86] | 0.96 [1.02] | 0.89 [0.94] | 0.97 [0.99] | 0.92 [0.89] | |

| CP | 0.93 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.96 | |

| β1(1) | Mean | 0.95 (0.46) | 0.97 (0.47) | 0.95 (0.41) | 0.98 (0.42) | 0.95 (0.31) | 0.98 (0.37) |

| %Bias | -5.11 | -3.31 | -5.18 | -2.11 | -5.21 | -2.11 | |

| 0.51 [0.48] | 0.44 [0.48] | 0.26 [0.39] | 0.41 [0.43] | 0.31 [0.29] | 0.40 [0.41] | |

| CP | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | |

| Mean | 0.34 (0.94) | 0.61 (0.39) | 0.41 (0.91) | 0.67 (0.38) | 0.56 (0.76) | 0.73 (0.34) |

| %Bias | -59.04 | -26.51 | -50.60 | -19.28 | -32.53 | -12.05 | |

| σ12(0.42) | Mean | 0.80 (0.64) | 0.53 (0.58) | 0.81 (0.53) | 0.42 (0.38) | 0.75 (0.50) | 0.40 (0.39) |

| %Bias | 90.48 | 26.19 | 92.86 | 0.09 | 78.57 | -4.76 | |

| Mean | 2.07 (1.19) | 2.85 (1.08) | 2.22 (1.44) | 2.97 (1.99) | 2.20 (1.32) | 2.88 (1.70) |

| %Bias | -56.24 | -39.75 | -53.07 | -37.21 | -53.49 | -39.11 | |

| δε(−2) | Mean | - | -0.48 (1.75) | - | -0.91 (1.25) | - | -0.90 (1.04) |

| %Bias | - | 76.01 | - | 54.50 | - | 54.99 | |

| - | 0.60 [0.72] | - | 1.23 [1.22] | - | 1.03 [1.04] | |

| CP | - | 0.87 | - | 0.91 | - | 0.95 | |

| δ1(2) | Mean | - | 1.03 (0.97) | - | 1.13 (0.97) | - | 1.16 (0.92) |

| %Bias | - | -48.51 | - | -43.49 | - | -42.00 | |

| - | 1.01 [1.00] | - | 1.04 [1.01] | - | 0.99 [0.96] | |

| CP | - | 0.53 | - | 0.61 | - | 0.66 | |

| Mean | 0.35 | 0.38 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Mean | 0.14 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.33 |

| AIC | Mean | 578.22 | 576.34 | 3824.31 | 3814.72 | 7662.07 | 7713.55 |

| BIC | Mean | 600.20 | 607.12 | 3854.34 | 3856.77 | 7695.56 | 7681.25 |

| HQ | Mean | 586.78 | 588.32 | 3835.11 | 3829.84 | 7673.70 | 7678.562 |

Mean value and root mean square error (in parentheses), percentage of bias (%Bias), mean standard error (SE) and sample standard deviation (in square brackets), coverage probability (CP) of estimates, coefficient of determination (R2) and averages of AIC, BIC and HQ criteria for sample sizes (n) of 100, 500 and 1000.

Notes: In the first column (Parameters), model parameters are followed by their respective true values in parentheses;—means “not applicable”; the coverage probability (CP) is the probability that an approximate confidence interval (assuming asymptotic normality for the model parameter) contains the true parameter value.

| Parameters | Measures | n = 100 | n = 500 | n = 1000 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT-link | SGT-link | GT-link | SGT-link | GT-link | SGT-link | ||

| β0(−1) | Mean | -1.40 (1.54) | -1.17 (1.31) | -1.25 (1.22) | -1.11 (1.09) | -1.11 | -1.02 (0.09) |

| %Bias | -39.17 | -17.33 | -24.56 | -11.4 | 11.41 | -2.09 | |

| 0.96 [0.89] | 0.64 [0.55] | 0.83 [0.92] | 0.60 [0.51] | 0.89 [0.86] | 0.40[0.37] | |

| CP | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.95 | 0.98 | 0.96 | 0.98 | |

| β1(1) | Mean | 0.98 (0.37) | 1.01 (0.33) | 0.99 (0.36) | 1.01 (0.16) | 0.98 (0.22) | 1.00 (0.09) |

| %Bias | -2.19 | 1.10 | -1.14 | 1.23 | -1.98 | 0.37 | |

| 0.32 [0.29] | 0.28 [0.32] | 0.23 [0.28] | 0.11 [0.16] | 0.28 [0.21] | 0.09 [0.10] | |

| CP | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.98 | |

| Mean | 0.37 (0.55) | 0.86 (0.16) | 0.40 (0.56) | 0.84 (0.09) | 0.53 (0.63) | 0.84 (0.07) |

| %Bias | -55.45 | 3.61 | -51.80 | 1.20 | -36.14 | 1.20 | |

| σ12(0.42) | Mean | 0.68 (0.61) | 0.36 (0.31) | 0.71 (0.56) | 0.38 (0.23) | 0.66 (0.56) | 0.38 (0.09) |

| %Bias | 61.91 | -14.29 | 69.05 | -9.52 | 57.14 | -9.52 | |

| Mean | 2.29 (1.23) | 4.56 (1.51) | 2.33 (1.17) | 4.55 (1.29) | 2.34 (1.11) | 4.58 (1.31) |

| %Bias | 51.59 | -3.59 | -50.74 | -3.81 | -50.53 | -3.17 | |

| δε(−2) | Mean | - | -2.18 (1.06) | - | -2.12 (1.04) | - | -2.06 (0.99) |

| %Bias | - | -9.00 | - | -6.02 | - | -3.04 | |

| - | 1.44 [1.04] | - | 1.04 [1.05] | - | 0.88 [0.98] | |

| CP | - | 0.94 | - | 0.96 | - | 0.97 | |

| δ1(2) | Mean | - | 1.64 (1.18) | - | 1.69 [1.16] | - | 1.84 [1.04] |

| %Bias | - | -18.13 | - | -15.50 | - | -8.10 | |

| - | 1.13 [1.18] | - | 1.16 [1.17] | - | 1.02 [1.03] | |

| CP | - | .90 | - | 0.94 | - | 0.96 | |

| Mean | 0.34 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.40 | 0.58 |

| Mean | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.26 | 0.52 |

| AIC | Mean | 578.04 | 524.06 | 3820.10 | 3804.12 | 7657.13 | 7652.56 |

| BIC | Mean | 601.18 | 597.24 | 3853.79 | 3852.17 | 7689.12 | 7671.17 |

| HQ | Mean | 588.01 | 575.75 | 3834.30 | 3821.40 | 7667.66 | 7542.49 |

Mean value and root mean square error (in parentheses), percentage of bias (%Bias), mean standard error (SE) and sample standard deviation (in square brackets), coverage probability (CP) of estimates, coefficient of determination (R2) and averages of AIC, BIC and HQ criteria for sample sizes (n) of 100, 500 and 1000.

Notes: In the first column (Parameters), model parameters are followed by their respective true values in parentheses;—means “not applicable”; the coverage probability (CP) is the probability that an approximate confidence interval (assuming asymptotic normality for the model parameter) contains the true parameter value.

Clearly, the SGT-link model adjusted better with non normal data and accordingly, random effects prediction is better with SGT-link model (R2 ≥ 0.49) than with the probit or the skew-probit model. Moreover, all the considered model selection criteria namely AIC, BIC and HQ on average correctly selected the SGT-link model as the preferred model.

Application to the respiratory infection data

To demonstrate the usefulness of the proposed approach to correlated binary data modeling, we revisited the respiratory illness data (available in geepack package [57] in R) which was used by [24] to illustrate their t-link GLMM. The respiratory illness data was obtained from a clinical study of the effect of a treatment on 111 patients with respiratory illness, recruited from two different clinical centers. The patients were examined and their respiratory state (categorized as 1 = good, 0 = poor) determined (baseline). They were then randomized to receive either placebo or an active treatment. The goal of the study was to determine whether the treatment induced a better respiratory state in treated patients. The outcome is the respiratory state measured at four visits for each patient as good (y = 1) or poor (y = 0). In addition to the treatment (treat = 0 for placebo group (P) and treat = 1 for treated group (A)), the following fixed covariates were included: the clinical center (center = 0 for the first center and center = 1 for the second center), the baseline (respiratory state at the first visit), gender (sex = 0 for female (F) and sex = 1 for male (M)) and the interaction of treatment and gender. Following [24], we assumed that the age effect is patient-specific (random slope) and thus considered the patient age centered around its median (31 years) as a random covariate. Since the fixed covariates included binary variables (treat, gender, center and baseline), a conditional skew-probit model is not identifiable given random effects and we thus set δϵ = 0 to ensure identifiability.

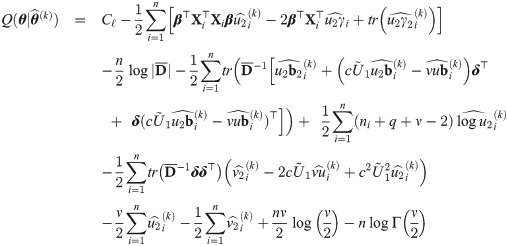

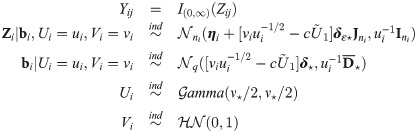

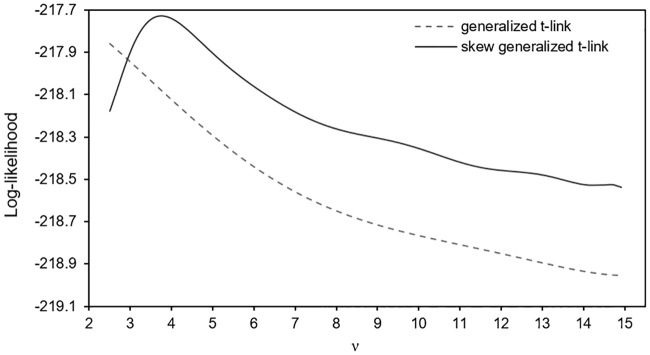

For the purpose of comparison, we fitted the probit, skew-probit, GT-link and SGT-link models. We initialized fixed effects β and the random slope skewness parameter δ to zero whereas the random slope scale was initialized to one. For the GT-link and the SGT-link models, we considered the model selection approach of [51] with degrees of freedom ν = 2.5, 2.6, …, 15.

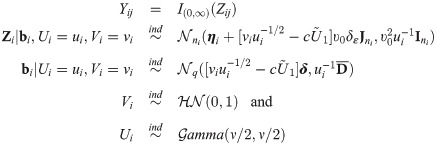

As depicted in Fig 1, the profiled marginal log-likelihood for the GT-link model is unbounded, with smaller ν corresponding to better fit in accordance with the t-link model fits in [24] (ν ≤ 4). We thus set ν = 2.5 for the t-link model. For the SGT-link fit, Fig 1 indicates that the log-likelihood is bounded with a maximum at ν = 3.7, suggesting heavy tail link function and random slope distributions. The difference in the behaviours of the GT-link and SGT-link models may be explained by the implication of ν in the location of the skew t-link model through

Fitting the generalized t-link and the skew generalized t models to the respiratory infection data: Plot of the marginal log-likelihood profiled for the degrees of freedom ν.

The maximum likelihood (ML) estimates under the probit, skew-probit, GT-link and SGT-link models (Table 6) are somewhat close for the four fitted models which all show that respiratory illness is associated to clinical center, baseline state and treatment, with the treatment effect varying with gender. The SGT-link fit additionally indicates that, irrespective of the treatment, the respiratory state is poorer for male patients (Table 6,

| Parameter (variable) | Probit | Skew probit | GT-link (ν = 2.5) | SGT-link (ν = 3.7) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| estimate | se | z value | estimate | se | z value | estimate | se | z value | estimate | se | z value | |

| β0 (Intercept) | 0.3429 | 0.4994 | 0.6866 | 0.4527 | 0.5012 | 0.9031 | 0.3570 | 0.5491 | 0.6502 | 0.5383 | 0.4659 | 1.1555 |

| β1 (center = 2) | 0.6292 | 0.2639 | 2.3846 | 0.6890 | 0.2611 | 2.6391 | 0.6767 | 0.2101 | 2.9410 | 0.5993 | 0.2395 | 2.5026 |

| β2 (baseline) | 1.6689 | 0.2900 | 5.7544 | 1.6312 | 0.2837 | 5.7499 | 1.8100 | 0.4118 | 4.3952 | 1.5152 | 0.2584 | 5.8627 |

| β3 (sex = M) | -0.8228 | 0.5218 | -1.5768 | -1.0170 | 0.5293 | -1.9216 | -0.8833 | 0.5274 | -1.6748 | -1.0129 | 0.4944 | -2.0489 |

| β4 (treat = P) | -2.1198 | 0.6018 | -3.5224 | -2.0980 | 0.5958 | -3.5215 | -2.2634 | 0.7910 | -2.8615 | -2.0398 | 0.5366 | -3.8010 |

| β5 (M×P) | 1.3840 | 0.6461 | 2.1419 | 1.4055 | 0.6403 | 2.1950 | 1.3251 | 0.6300 | 2.1033 | 1.3425 | 0.5867 | 2.2884 |

| δ (age) | - | - | - | 0.0411 | 0.0216 | 1.9011 | - | - | - | 0.0262 | 0.0139 | 1.8906 |

| σ 2 (age) | 0.0117 | 0.0050 | - | 0.0113 | 0.0049 | - | 0.0143 | 0.0061 | - | 0.0118 | 0.0059 | - |

| AIC | 455.6305 | - | - | 453.7766 | - | - | 453.2140 | - | - | 451.4658 | - | - |

| BIC | 484.3013 | - | - | 486.5432 | - | - | 485.9399 | - | - | 484.2324 | - | - |

| HQ | 466.9370 | - | - | 466.6983 | - | - | 465.7514 | - | - | 464.3875 | - | - |

Notes: M = male patient; P = placebo; M×P is a shortcut for sex = M×treat = P; σ2 and δ are the variance and the skewness parameter respectively for the patient-specific slope of median centered age (year); se = standard error; z value = estimate/se (a z value ≥1.96 roughly indicates 5% significance assuming asymptotic normality of z values);—means “not applicable”

Conclusion

This work has considered the skew generalized t class of distributions for both link and random effects distributions in mixed models for binary data. The objective was to improve the exploitation of binary data bearing oddities such as skewness and tails thicker/thinner than the normal distribution. To allow inference in such models, we developped a maximum likelihood estimation procedure based on the EM algorithm. We combined results from [34] and [37] to obtained expressions for computing moments of truncated multivariate skew t distributions. The computation used existing R functions for the multivariate skew t cumulative distribution function. Our simulation experiment showed that, irrespective of sample size, the SGT-link model outperforms the probit GLMM when the underlying data generation mechanism is not normal. We also demonstrated that the skew generalized-link model performed better than the skew-probit and the generalized t-link GLMMs, when the underlying data is both skewed and heavy tailed.

An important finding is that when the model degrees of freedom ν is small and very large values are assumed (fitting probit and skew-probit models), the estimates of fixed effects are biased, whereas when ν is large but small values are assumed, the estimates of fixed effects are not biased. Moreover, asymptotic inference using information based standard errors proved highest ability accuracy in detecting spurious skewness in large samples (n ≥ 500) and information criteria on average selected the correct model fit for all tested sample sizes (n = 100, 500, 1000). These findings extend results in [24] on t-link GLMM to SGT-link GLMM, asserting that information criteria are reliable for selecting the best model for a particular dataset.

However, the simulation experiments revealed that the EM algorithm has a high computational cost. For instance, in a model with q = 2 random effects, n = 100 clusters and ni = 6 observations per cluster, the mean running time for the SGT-link model fit was 4.76 minutes which is almost 135 times the time required by the probit model fit (2.12 seconds). Our implementation relies on the pmst function of the R package sn [35] to compute the cumulative probabilities of skew t distributions. This function uses the one dimensional routine integral of R on the multivariate normal cumulative distribution function. The use of the EM algorithm for large q values (e.g. q = 10, 15) requires the prior development of a faster routine for the computation of cumulative probabilities of skew t distributions. This will make the EM algorithm scalable for large q + ni. On multicore plateformes, parallel computing can also substantially speed computations up. The expressions provided for computing moments of truncated multivariate skew t distributions is limited to work for models with ν > 2. The use of formulae given in [38] will extend our EM algorithm to very small degrees of freedom (1 < ν ≤ 2).

Binary data related to very rare events often require special treatment and are generally analysed using zero inflated models [58]. The development of a skew generalized t-link model with zero inflation can significantly improve the exploitation of such data. In addition to binary data, GLMMs handle other data types like count, proportional and ordinal outcomes. From the good performance demonstrated in this work and in previous related ones [9, 24], we believe that the simultaneous introduction of flexible links and random effects distributions in GLMM would benefit knowledge extraction from observed data in applied research fields where advances rely on modeling capacity.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the editor and two referees for their relevant comments and suggestions. They are also grateful to Matthews Lazaro (Kamuzu College of Nursing, Lilongwe, Malawi) for the time he devoted to edit the manuscript for language usage, spelling, and grammar.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

Inference in skew generalized t-link models for clustered binary outcome via a parameter-expanded EM algorithm

Inference in skew generalized t-link models for clustered binary outcome via a parameter-expanded EM algorithm