- Altmetric

The use of hydrogen as a clean and renewable alternative to fossil fuels requires a suite of flammability mitigating technologies, particularly robust sensors for hydrogen leak detection and concentration monitoring. To this end, we have developed a class of lightweight optical hydrogen sensors based on a metasurface of Pd nano-patchy particle arrays, which fulfills the increasing requirements of a safe hydrogen fuel sensing system with no risk of sparking. The structure of the optical sensor is readily nano-engineered to yield extraordinarily rapid response to hydrogen gas (<3 s at 1 mbar H2) with a high degree of accuracy (<5%). By incorporating 20% Ag, Au or Co, the sensing performances of the Pd-alloy sensor are significantly enhanced, especially for the Pd80Co20 sensor whose optical response time at 1 mbar of H2 is just ~0.85 s, while preserving the excellent accuracy (<2.5%), limit of detection (2.5 ppm), and robustness against aging, temperature, and interfering gases. The superior performance of our sensor places it among the fastest and most sensitive optical hydrogen sensors.

Detecting hydrogen is important for development of renewable energy sources. Here, the authors present lightweight optical hydrogen sensors based on a metasurface of PdCo nano-patchy particle arrays, which achieve sensitive hydrogen detection in less than 1 s, and without risk of sparking.

Introduction

Hydrogen fuel is a key energy carrier of the future, and it is the most practical alternative to fossil fuel-based chemical storage, with a high theoretical energy density and universality of sourcing1. However, significant challenges remain with respect to the safe deployment of hydrogen fuel sources and therefore its widespread adoption2. For hydrogen leakage detection and concentration controls, it is essential that hydrogen sensors have good stability, high sensitivity, rapid response time, and most importantly be “spark-free”3,4. High performance hydrogen sensors are, however, not only of importance in future hydrogen economy but also the chemical industry5, food industry6,7, medical applications8, nuclear reactors9, and environment pollution control10.

Numerous optical hydrogen sensors based on hydride-forming metal plasmonic nanostructure have been explored11,12. Pd is the most common hydriding metal for sensor applications due to its rapid response, room temperature reversibility, and relative inertness13. However, pure Pd nanoparticles suffer from the coexistence of an α–β mixed phase region, inducing hysteresis and hence non-specific readout and limited reaction rate12,14,15. It is possible to minimize this hysteresis and boost the reaction kinetics through the incorporation of alloying metals, such as Co, Au, or Ag11,12,16. It has been believed that the enhanced reaction kinetics in the alloying metal hydrides is associated with the reduction of the enthalpy of formation due to the reduced abrupt volume expansion/contraction occurring in smaller mixed phase regions, resulting in a reduction of energy barrier for hydride formation/dissociation, and the improved diffusion rate upon (de)hydrogenation12,15,17–20. Synergistically with material design, various sensing nanostructures have been engineered to minimize the volume-to-surface ratio (VSR) of the sensor, a critical condition for achieving fast response time and low hysteresis12. These structures include nanostripes21, nanoholes22,23, lattices23, nanobipyramids24, hemispherical caps23, nanowires, mesowires25, and chiral helices26,27. Moving beyond metals, other materials such as polymers can be incorporated, as Nugroho et al.11 recently demonstrated, significantly boosting the sensitivity and response time of a Pd-based nanosensor. Along with downsizing the active material layer, the benchmark response time of 1 s at 1 mbar H2 and 30 °C has been achieved11, however optical contrast was sacrificed. As a result, sub-second response time and ppm limit of detection (LOD) have not been achieved in a single sensor (Supplementary Table 1).

In this work, we demonstrate a compact optical hydrogen sensing platform with the fastest response reported to date and sub-10-ppm LOD. The sensor is comprised of Pd and Pd-alloy nano-patchy (NP) arrays with a simple optical transmission intensity readout. These hexagonally packed nano-arrays are generated by facile single metal glancing angle deposition (GLAD) on polystyrene (PS) nanosphere monolayers. This fabrication process requires just one deposition step with no post-processing required, simplifying scale-up and reducing costs. The tunable film thickness, patchy diameter and shape (hemispheres or donuts), and therefore VSR can be readily controlled, resulting in tunable and rapid response rate. By alloying with cobalt, the response time of the metasurfaces was reduced below 0.85 s from 1 to 100 mbar of H2 partial pressure, surpassing the strictest requirements for H2 sensing while preserving excellent accuracy (<2.5% full scale) and 2.5-ppm LOD. In a broader perspective, our work illustrates evolution in hydrogen gas sensor technologies through rational topological design and targeted integration of non-traditional materials, such as polymers and active alloying elements. These concepts are universal for promoting strong interactions between gas and materials and may be generally applied to advance sensor and catalyst development, among others.

Results and discussion

Pd NP-based optical hydrogen sensors

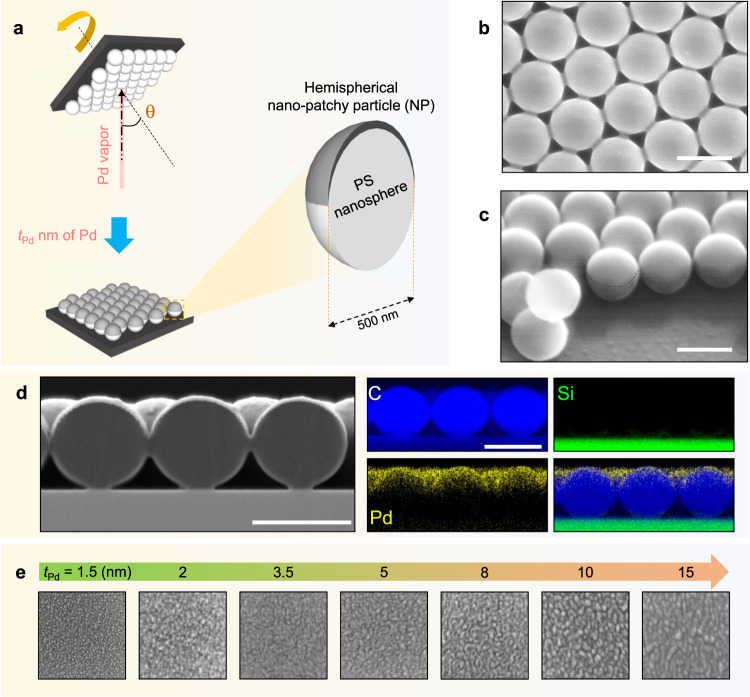

The fabrication scheme and nanoarchitecture of an optical hydrogen sensor based on a hexagonal array of Pd hemispherical NPs are depicted in Fig. 1a (see Methods and Supplementary Figs. 1–5). A vapor incident angle of θ 50° was chosen to ensure that the film would not be deposited directly onto the underlying glass substrate (Supplementary Fig. 2)23. The designed structure consists of NP arrays on top of hexagonal closed-packed nanosphere monolayer, which is confirmed by SEM and energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (see Fig. 1b–d and Supplementary Figs. 6–8). Note that NP samples with a specific deposited thickness will now be referred to as

Fabrication scheme and morphology characterization.

a Schematic of the fabrication process. b Top-view and c side-view scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of Pd

The morphological transition of Pd

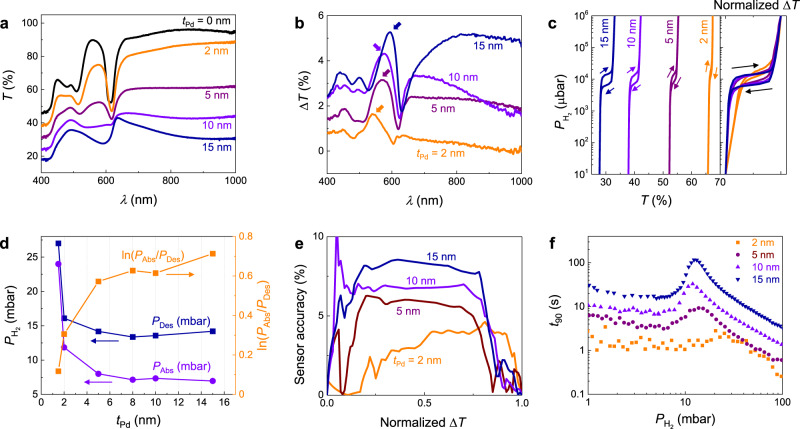

The transmission magnitude of the Pd metasurfaces monotonically increases and approaches that of a bare PS nanosphere monolayer with decreasing tPd (Fig. 2a). Effects from the PS monolayer are observed in the transmission spectra of all films, such as the optical band gap located at wavelength λ = 618 nm and other transmission maxima/minima at shorter wavelengths due to interference effects29. Upon hydrogenation, the optical transmission (

Pd

a Experimental optical transmission spectra T(λ) (at

Optical hydrogen sorption isotherm of

Figure 2d displays the plateau pressure of absorption isotherm, desorption isotherm, and hysteresis (PAbs, PDes, and ln(PAbs/PDes), respectively) versus tPd (the extraction method is described in Supplementary Fig. 16). We observe a critical thickness (tPd ≈ 5 nm) above which the nanoparticles behave qualitatively differently than for thicknesses below. It is worthwhile to note that this critical thickness corresponds well with the expected transition from a separated island-like morphology to a percolating film morphology. Above this critical thickness, PAbs and PDes are relatively independent of tPd and ln(PAbs/PDes) = 0.62, which is the value predicted for bulk Pd undergoing a coherent phase transition33. Below the critical thickness, both PAbs and PDes sharply increase, while ln(PAbs/PDes) sharply decreases. This change in PAbs and PDes is due to the increasing effects of higher energy subsurface adsorption sites relative to bulk sites32,34. The significant decrease in hysteresis for shrinking particle size at a constant temperature of Pd material, T, has been widely observed and is understood as a decrease in critical temperature, Tc, with decreasing the particle size (Supplementary Fig. 11)35. In general, when T is close to Tc, the hysteresis behavior is strongly suppressed. See Supplementary Figs. 11–13 for more in-depth analyses of PAbs, PDes, and ln(PAbs/PDes) as functions of tPd.

Performance of Pd metasurfaces

The hysteresis of an optical sensor, and therefore its insensitivity to measurement history, can be calculated in terms of “sensor accuracy”, as proposed by Wadell et al. (Supplementary Equation (20))36. Figure 2e summarizes the sensor accuracy of

The response time of the NP sensor is improved with decreasing tPd. The response times (t90, the time required to reach 90% of the final equilibrium response) of

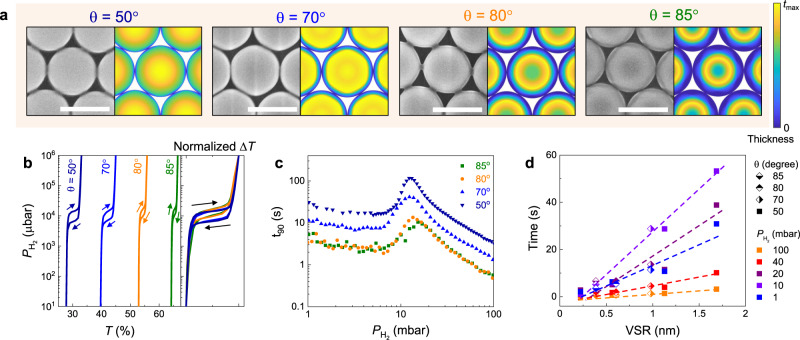

The flexibility of the GLAD technique allows the realization of different nanopatterns of patchy array sample by adjusting the polar and azimuthal angle of deposition onto the packed nanosphere monolayers (Supplementary Figs. 2−3)42. Here, we utilize θ = 70°, 80°, and 85° with constant azimuthal rotation (fixed tPd = 15 nm) to engineer the morphology and VSR of NPs. Figure 3a displays SEM micrographs of

Pd

a Top-view SEM images (left) and corresponding simulated morphologies (right) of pure Pd NP samples, fabricated with vapor incident angle of θ = 50°, 70°, 80°, and 85°, respectively. Scale bars correspond to 500 nm, and the color bar shows the Pd thickness distribution in the simulated hemisphere cap. b Optical hydrogen sorption isotherm of NP with different θ, extracted at ΔT(λ) maxima. Arrows denote the sorption direction. The panel to the right shows corresponding normalized ΔT(λ) hydrogen sorption isotherm of NP with different θ. c Response time of NP sensors with pulse of hydrogen pressure from 1 mbar to 100 mbar. d Response time of NP samples as a function of volume-to-surface ratio of NP sensors, at different hydrogen pressure. Note that the optical isotherm data of

As mentioned, a key advantage of this nano-fabrication method is the straightforward engineering of the VSR, which can decrease sensor response times11. By increasing θ, one can efficiently reduce VSR since the patchy pattern gradually transforms from hemisphere-like to donut-like structures. A strong

Pd-composite NP optical hydrogen sensors

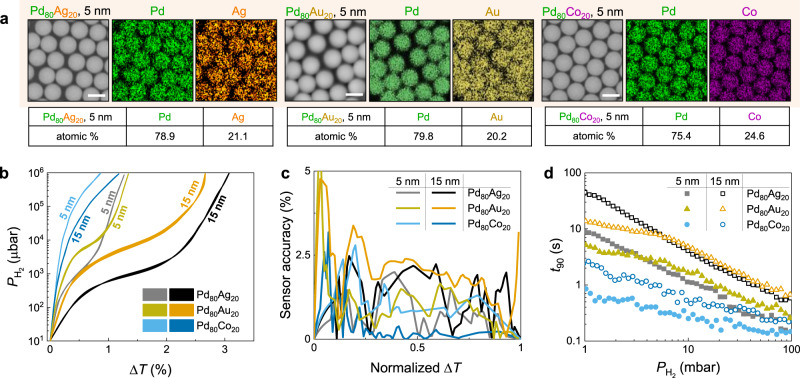

To further optimize the accuracy and response time of the nano-sensor, we utilized Pd-based composites with alloying elements (Ag, Au, or Co) to modify the hydriding properties of Pd. For example, PdAg and PdAu alloys display lower plateau pressures than pure Pd11,23,36,44, while PdCo alloys display much higher plateau pressures45,46. Pd80Ag20, Pd80Au20, and Pd80Co20 composite

Composite NP sensors.

a SEM and EDS images of Pd80Ag20, Pd80Au20, and Pd80Co20 (t = 5 nm) composite NP samples. Scale bars correspond to 500 nm. Tables show the elemental atomic composition (at. %) of the Pd80Ag20 and Pd80Co20 NPs, which are consistent with the desired compositions. b Optical hydrogen sorption isotherm of composite NP, extracted at ΔT(λ) maxima. c Sensor accuracy of composite NP sensors at specific normalized ΔT readout over hydrogen pressure range of 101 μbar to 106 μbar. d Response time of NP sensors with pulse of hydrogen pressure from 1 mbar to 100 mbar.

The hydrogen sorption characteristics of the Pd80Ag20 alloy NP system are examined as previously (Supplementary Fig. 19). The plateau of Pd80Ag20 NP is shifted downward to lower pressure (PAbs = 1 mbar) and shows an increasing slope in comparison to that of the Pd NP (Supplementary Fig. 19c). The hysteresis is very narrow (PHys are <0.1 mbar and <0.05 mbar in Pd80Ag20

In comparison to PdAg system, PdAu samples with the same thickness exhibits a similar spectra shape and transmission magnitude (Supplementary Fig. 19a). Upon the hydrogenation, Pd80Au20

Several advantages are achieved through the utilization of a PdAg and PdAu composite instead of pure Pd in a representative

While the advantages (1)-(3) achieved by Pd80Ag20 and Pd80Au20

In order to reduce the response time further, the sorption behavior of the NP sensors was modified through the incorporation of Co (Pd80Co20), analogous to Pd80Ag20 and Pd80Au20. A PdCo alloy improves the kinetics of hydrogenation over a PdAg and PdAu alloy by (1) remaining in the α-phase over the pressure region of interest, which removes the kinetic steps of the α- to β-phase transition and subsequent hydrogen atomic diffusion through the β-phase55; and (2) cobalt offers a greater metal-hydrogen bond strength than silver, which could facilitate dissociative chemisorption of hydrogen56. It is also worth noting that the comparison between the PdAu and PdCo NP sensors allows isolation of the alloying element effect since their morphologies are very similar (Supplementary Fig. S10). In the Pd80Co20 sensors, the overall shape of ΔT(λ) is similar to those of the Pd, Pd80Ag20, and Pd80Au20 sensors. However, the magnitude of ΔT is significantly smaller as PdCo alloy has lower H-solubility due to lattice contraction (Supplementary Fig. 19)45.

Figure 4b shows the ΔT−

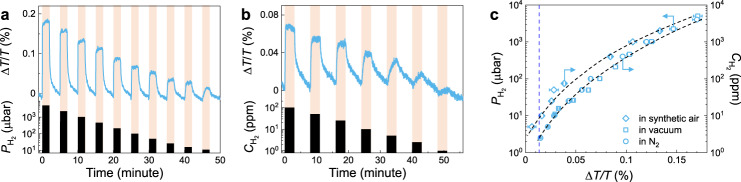

One shortcoming of downsizing the active material layer is that the optical contrast upon (de)hydrogenation decreases significantly, which makes it challenging to achieve ultra-fast response time and ultra-low LOD in a single nano-sensor. The unique design of the NP sensor allows for a very high surface coverage (>90%, Supplementary Fig. 17) and results in sizable optical contrast even at very low concentration of hydrogen. In Fig. 5a, the detection capability of the PdCo

Sensing performances of composite PdCo NP sensors.

a ΔT/T response of Pd80Co20

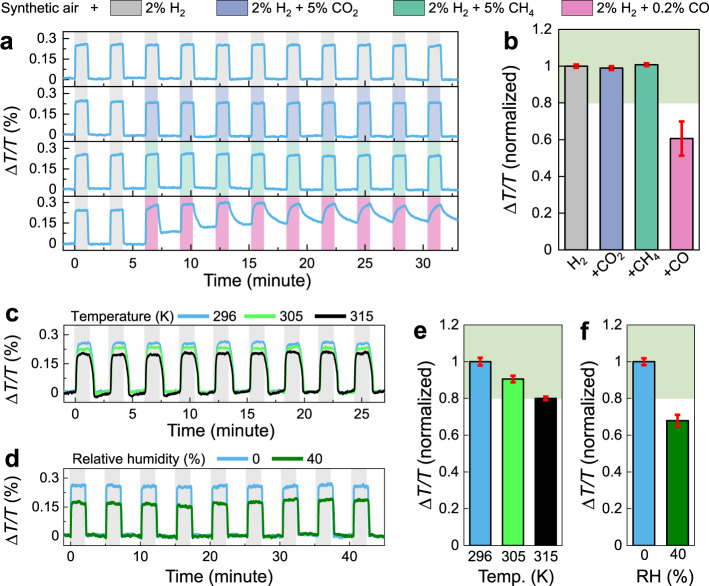

In order to assess the practical implementation of these hydrogen sensors, the influence of temperature, moisture, and interfering gases (e.g., CO, CO2, CH4) on the sensor performances were investigated. For the PdCo

Sensing performances of composite PdCo NP sensors.

a Time-resolved ΔT/T response of Pd80Co20

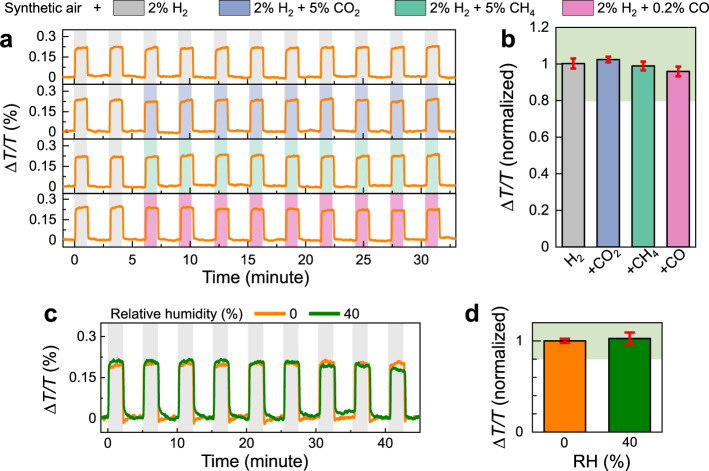

Inspired by previous works11,58,59, our preliminary results demonstrate that a simple polymer coating layer of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) achieved by spin-coating can provide excellent protection for PdCo

Sensing performances of composite PdCo NP/PMMA sensors.

a Time-resolved ΔT/T response of Pd80Co20

In summary, we have demonstrated a method to produce a class of rapid-response, highly sensitive, and accurate optical Pd-alloy hydrogen sensors through GLAD on PS-nanospheres. It is facile to tune these metasurface sensors through simple alloying, angle of deposition, or film thickness, which dictates the qualitative nature, quantitative metrics, and hysteresis of the response. By incorporating 20% Co, the sensor response time (t90) at 1 mbar is less than 0.85 s, which is the fastest response ever reported at the critical H2 concentration required for leak detection. Additionally, these sensors readily detect concentration as a low as 2.5 ppm in nitrogen and 10 ppm in air, maintain high accuracy due to the hysteresis-free operation, and exhibit robustness against aging, temperature, moisture, and interfering gases. These sensors demonstrate a viable path forward to spark-proof optical sensors for hydrogen detection applications.

Methods

Materials

Polystyrene (PS) nanospheres (Polysciences Inc., D = 500 ± 10 nm) and ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, 98%) were used to create the nanosphere monolayers. Palladium (99.95%), silver (99.99%), and cobalt (99.95%) from Kurt. J Lesker Company were utilized for electron beam depositions. Deionized water (18 MΩ cm) was used for all experiments.

Sample fabrication

Hexagonal close-packed nanosphere (D = 500 nm) monolayers on glass and Si substrates (1 × 1 cm2), which were prepared by an air/water interface method23,63–65, were used as a template for electron beam deposition. For pure Pd NP samples, the substrates were coated by Pd with a varied thickness of tPd, under a constant deposition rate of 0.05 nm/s, and the sample holder rotated azimuthally with a constant rotation rate of 30 rpm during deposition process. For Pd-Ag, Pd-Au or Pd-Co composite NP sample, materials were placed in two independent crucibles on two sides of the chamber, and the vapor incident angles to substrate normal were 10° and −10°, respectively. The deposition rates and thicknesses of Pd and Ag/Au/Co were monitored independently by two separated quartz crystal microbalances (QCM). By controlling the deposition rates of Pd and Ag/Au/Co, Pd80Ag20, Pd80Au20, and Pd80Co20 NPs were realized.

Morphology and composition characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed with a Thermo Fisher Scientific (FEI) Teneo field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM). Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping was performed with 150 mm Oxford XMaxN detector. Ultra-high-resolution SEM was performed with a SU-9000, Hitachi (with resolution of 0.4 nm at 30 kV).

Hydrogen sensing measurement

All optical isotherm, LOD, response/release time measurements are performed in a home-made vacuum chamber with two quartz windows23. The hydrogen pressure was monitored by three independent pressure transducers with different which cover the pressure range of 10−6 to 1.1 bar (two PX409-USBH, Omega and a Baratron, MKS). Optical transmission measurements were performed with an unpolarized collimated halogen lamp light source (HL-2000, Ocean Optics) and a spectrometer (USB4000-VIS-NIR-ES, Ocean Optics). The optical response/release time measurements were performed at 12.5 Hz sampling frequency (4 ms integration time with 10 averages). The LOD measurements were performed at 1.25 Hz sampling frequency (4 ms integration time with 100 averages), and ΔT/T responses were averaged over wavelength range of λ = 500–660 nm for the best SNR. For LOD measurements in flow mode, ultra-high purity hydrogen gas (Airgas) was diluted with ultra-high purity nitrogen gas (Airgas) or synthetic gas (Airgas) to targeted concentrations by commercial gas blenders (GB-103, MCQ Instruments). The gas flow rate was kept constant at 400 ml/min for all measurements. All experiments (except the temperature-dependent experiments) were performed at constant 25 °C.

FDTD calculations

FDTD calculations of Pd hydride NP samples were carried out using a commercial software (Lumerical FDTD Solutions)66. The geometric parameters of Pd cap were obtained from MATLAB simulation. The mesh size of 2 × 2 × 2 nm was chosen. The refractive index of glass and PS was chosen to be 1.5 and 1.59, respectively, and the optical parameters of Pd and PdHx were extracted from ref. 67.

PMMA coating

PMMA (Sigma Aldrich, 10 mg/ml dissolved in acetone by heating up the mix to 80 °C and cooling down to the room temperature, Mw = 15,000) was spin-coated on sensors at 5000 r.p.m. for 120 s followed by a soft baking at 85°C on a hotplate for 20 min. Using the same coating process on a clean glass substrate results in a ~50 nm PMMA film, as measured by an atomic force microscope (NX-10, Park Instrument).

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22697-w.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. Yiping Zhao for his generosity in sharing his nano-fabrication tools with us. This work was supported by Savannah River National Laboratory’s Laboratory Directed and Development program (SRNL is managed and operated by Savannah River Nuclear Solutions, LLC under contract no. DE-AC09-08SR22470). M.H.P. acknowledges support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering under Award No. DE-FG02-07ER46438 and the University of South Florida Nexus Initiative (UNI) under Award No. R15301.

Author contributions

H.M.L. designed and fabricated the samples, performed the sensing experiments, performed FDTD simulations, analyzed the experimental data, and wrote the first draft of the paper. M.T.P. and T.G. co-wrote and edited the paper. R.P.M. and M.H.P. performed SEM measurements and edited the paper. G.K.L. analyzed the experimental data, co-wrote the paper, and supervised the project. T.D.N. was responsible for project planning, group managing, and manuscript writing. All authors gave feedback on the final paper.

Data availability

The data that support the finding of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

Sub-second and ppm-level optical sensing of hydrogen using templated control of nano-hydride geometry and composition

Sub-second and ppm-level optical sensing of hydrogen using templated control of nano-hydride geometry and composition