- Altmetric

The biofunctionalization of particles with specific targeting moieties forms the foundation for molecular recognition in biomedical applications such as targeted nanomedicine and particle-based biosensing. To achieve a high precision of targeting for nanomedicine and high precision of sensing for biosensing, it is important to understand the consequences of heterogeneities of particle properties. Here, we present a comprehensive methodology to study with experiments and simulations the collective consequences of particle heterogeneities on multiple length scales, called superpositional heterogeneities, in generating reactivity variability per particle. Single-molecule techniques are used to quantify stochastic, interparticle, and intraparticle variabilities, in order to show how these variabilities collectively contribute to reactivity variability per particle, and how the influence of each contributor changes as a function of the system parameters such as particle interaction area, the particle size, the targeting moiety density, and the number of particles. The results give insights into the consequences of superpositional heterogeneities for the reactivity variability in biomedical applications and give guidelines on how the precision can be optimized in the presence of multiple independent sources of variability.

The biofunctionalization of micro- and nanoparticles with specific targeting moieties forms the basis of biomedical applications such as particle-based biomolecular assays and targeted nanomedicine.1−6 The specific targeting moieties are coupled to particles that can have various chemical compositions, e.g., metallic particles, polymer-based particles, and oxide-based particles. To achieve targeting and sensing with high precision, good control is needed of the particles and their biofunctionalization. Therefore, it is important to know the heterogeneities in the system and understand how these lead to variabilities in the targeting functionality of the particles.7,8 For example, heterogeneities in the particle surface (e.g., nonuniform chemical composition, surface roughness), heterogeneities in the targeting moieties (e.g., number and location of conjugation sites), and heterogeneities in the coupling processes (e.g., nonuniform reaction conditions) cause variabilities, such as variable densities of targeting moieties, variable orientations of the moieties, and variable functional activities. In that way, the underlying heterogeneities affect the number of molecular interactions that the particles can effectuate.

In this work we ask the question, how do multiple independent heterogeneities collectively determine the reactivity variability of particles? Here, reactivity is defined as the number of particle-coupled targeting moieties that are available for interaction toward a countersurface. The independent particle heterogeneities are referred to as superpositional heterogeneities, as the heterogeneities are superposed onto each other to generate the total observed reactivity variability. We address this question using three experimental techniques with single-molecule resolution and using simulations. Single-molecule techniques are able to count molecules and molecular events, revealing detailed heterogeneities and stochastic properties of biomolecular systems.9−16 Here, we use two fluorescence-based single-molecule techniques (qPAINT and DNA-PAINT) to identify individual targeting moieties on particles and gain insight in their number and spatial distribution.9,10 The reactivity variability is studied using a biosensing technique with both single-particle and single-molecule resolution, called biosensing by particle mobility (BPM).17−19 These techniques jointly cover all relevant length scales of the interactions of the particles. The data quantify the reactivity variability and how this reactivity variability scales as a function of the system parameters, namely, particle interaction area, particle size, targeting moiety density, and number of particles. The results provide insights into the origins of variability and give guidelines how particle-based biomedical applications can be engineered in such a way that a high precision is obtained.

Superpositional Heterogeneity

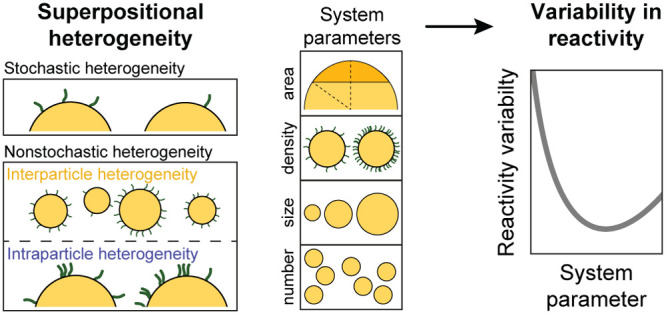

The concept of superpositional heterogeneity is explained in Figure 1, showing the various contributors and the distributions of reactivity caused by each individual contributor. Figure 1a sketches two important applications of biofunctionalized particles, namely, targeted nanomedicine and biosensing. In targeted nanomedicine applications, the biofunctionalized particles interact with a biological countersurface such as a vessel wall, a cell membrane, or a tissue. In particle-based biosensing, the particles interact with a biosensor substrate. In both cases, biofunctionalized particles form biomolecular bonds with a countersurface. In this work, we study how multiple heterogeneities of the particles cause reactivity variability, i.e., variability in the number of particle-coupled targeting moieties that are available for interaction toward a uniformly reactive countersurface. The reactivity variability is analyzed as a function of system parameters, such as particle size and density of targeting moieties on the particles.

Superpositional heterogeneity and how it determines reactivity variability. (a) Sketch of two applications of biofunctionalized particles: targeted drug delivery in nanomedicine (left) and sandwich assay biosensor with a particle as detection label (right). The reactivity variability is determined by the collective sum of stochastic and nonstochastic heterogeneities resulting in various numbers of targeting moieties on the particle surface. (b) Stochastic heterogeneity. Here, the width of the reactivity distribution is determined by Poisson statistics. Left: in case the targeting or sensing is effectuated by targeting moieties on the surfaces of many particles, then the total number of involved targeting moieties is large (indicative: 106–109 targeting moieties) and therefore the width of the reactivity distribution is narrow. Middle: when the targeting or sensing is caused by a single-particle measurement, a lower number of targeting moieties is involved (indicative: 103–106 targeting moieties), resulting in a larger reactivity variability. Right: if only a subparticle area is available for interaction to a countersurface, the number of targeting moieties is low (indicative: 100–103 targeting moieties), resulting in the broadest reactivity distribution. (c) Nonstochastic heterogeneities. Interparticle heterogeneity refers to targeting moiety variability between particles, e.g., due to size dispersion. Intraparticle heterogeneity refers to targeting moiety variability between different subparticle areas, e.g., due to nonuniform targeting moiety density. The observed reactivity distribution is determined by the superposition of stochastic, interparticle, and intraparticle heterogeneities, i.e., superpositional heterogeneity.

The reactivity variability can have stochastic and nonstochastic origins. Stochastic heterogeneity relates to the discrete nature of the targeting moieties, causing random placements of targeting moieties on the particle surface and distributions according to Poisson statistics. Nonstochastic heterogeneity refers to physical and chemical differences, such as particle size, surface roughness, and chemical surface heterogeneities. We subdivide the nonstochastic heterogeneity into two parts: heterogeneity between particles is called interparticle heterogeneity, and heterogeneity within particles is called intraparticle heterogeneity.

Figure 1b shows the stochastic heterogeneity of targeting moieties on the particle surface for three different reaction levels: ensemble level, single-particle level, and subparticle level. At ensemble level (left), the interaction is effectuated by a large ensemble of particles, where the total surface area of all particles contributes to this interaction. The total area is large, so many targeting moieties generate molecular interactions, resulting in a small reactivity variability between individual measurements. For a single-particle level (middle), where each particle is an individual effectuator, the total number of targeting moieties is much lower and therefore the distribution of reactivity per single-particle measurement is broader. The distribution is broadened even further when the interaction area is reduced to a fraction of the surface of a single particle (right).

The contributions of interparticle and intraparticle heterogeneity to the superpositional heterogeneity are visualized in Figure 1c. When these heterogeneities are present, the reactivity variability is larger than would be expected based on the stochastic contribution alone (gray dashed lines). The collective effect of stochastic, interparticle, and intraparticle heterogeneity results in the observed reactivity variability.

In the next section we will study how the reactivity variability is influenced by stochastic, interparticle, and intraparticle heterogeneities. The interparticle variability is quantified by measuring the number of active targeting moieties per particle, and the intraparticle variability is determined by mapping the locations of active targeting moieties on the particle surface. Subsequently, the reactivity variability is studied using biosensing by particle mobility. Finally, by simulations the reactivity variability is studied as a function of the system parameters: particle interaction area, targeting moiety density, particle size, and number of particles.

Results and Discussion

Interparticle Targeting Moiety Variability

The particles used in this work as a model system are commercially available silica particles with a diameter of 1 μm, functionalized with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) molecules as targeting moieties (see Materials and Methods). These particles are used in this study because they have a low size dispersion (CVsize = 5%) and a smooth surface (see Supporting Information Section 4). For each particle, the number of ssDNA molecules was quantified using a fluorescent imaging method with single-molecule resolution, namely, quantitative points accumulation in nanoscale topography (qPAINT).10,12,16 qPAINT makes use of the distribution of observed unbound times (i.e., dark times) of imager strands to targeting moieties in a region of interest (ROI), which depends on the number of these targeting moieties present in this ROI (see Supporting Information Section 1).

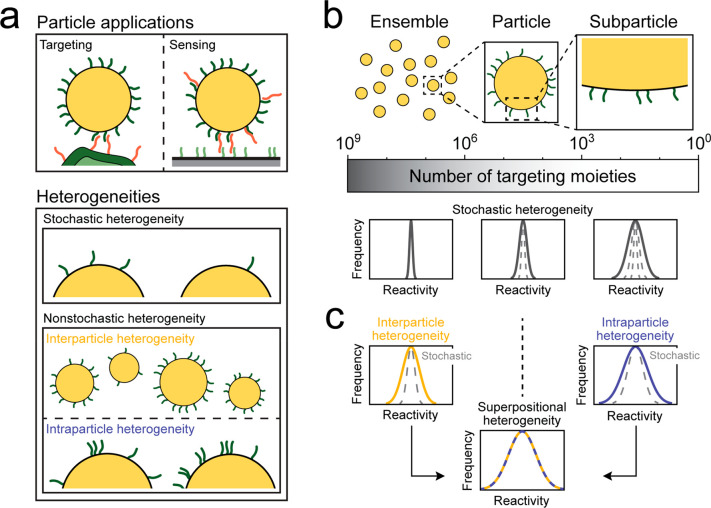

In Figure 2 the interparticle targeting moiety variability is quantified on the silica particles, which were functionalized with NeutrAvidin protein and subsequently incubated with a dilution series of biotinylated ssDNA molecules. Figure 2a shows the dependency of the number of active targeting moieties per particle quantified by qPAINT, as a function of the ssDNA to particle ratio present in solution during incubation (blue). For an increasing ratio, a linearly increasing number of targeting moieties per particle was observed (gray dashed line). This linear dependency is expected when the solution with biotinylated ssDNA molecules is depleted by the particles and the particles are not saturated. The found number of targeting moieties per particle is approximately a factor 2 lower than the ssDNA to particle ratio; this is in agreement with the fact that only half of the particle surface is observed due to illumination by total internal reflection (see Supporting Information Section 2.2).

Interparticle targeting moiety variability quantified using qPAINT experiments. (a) Number of targeting moieties (blue) as a function of the ssDNA to particle ratio in solution. The saturation point of (2.0 ± 0.2) × 105 targeting moieties per particle is determined by a supernatant assay (gray solid line; see Supporting Information Section 3). The values on the y-axis are the number of targeting moieties per particle (i.e., corrected for the fractional occupation of the NeutrAvidin proteins by the complementary ssDNA molecules in the qPAINT experiment; see Supporting Information Section 1.3). The gray dashed line indicates the linear relation (slope = 1) between the number ssDNA molecules per particle present in solution and the number of observed targeting moieties in the qPAINT experiment. The top x-axis indicates the total incubated ssDNA concentration (both complementary and noncomplementary DNA). The errors are the standard deviations. The inset shows the specificity of the qPAINT experiment by means of the number of localizations per particle for full match (FM) ssDNA and control (C) ssDNA with a random sequence. The box shows the median, 25th, and 75th percentiles, and the whiskers show the 5th and 95th percentiles. (b) Variability in the number of active targeting moieties per particle. The panels indicate the experimental results (left) and the simulated results (right). The observed CV is indicated in blue; the CV caused by the qPAINT measurement only is indicated in red. The CV caused by the qPAINT measurement shows a weak concentration dependency due to stochastics. Simulation: light blue includes only size variability (CVsize = 5%); dark blue includes size as well as targeting moieties density variability (CVdensity = 15%). The experimental data were measured in two fields of view with approximately 102 particles each. The errors are the fitting errors for the experiment, and the standard error for the simulation using 10 simulations with 102 particles per simulation.

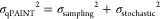

Figure 2b shows the experimentally found and simulated coefficient of variation (CV) of the number of targeting moieties per particle as a function of the incubated ssDNA concentration. Two CVs are indicated: the observed total CV (blue) and the CV induced by the qPAINT measurement (red). In the simulations it was assumed that the particle size has a normal distribution (CVsize = 5%; see Supporting Information Section 4) and that the solution with biotinylated ssDNA molecules is depleted by the particles. The variability in the number of targeting moieties induced by the qPAINT measurement σqPAINT can be described by

When comparing the experimental data to the simulated data, it appears that the variability in particle size and the qPAINT measurement variability together (light blue) are not sufficient to explain the CVmoiety observed in the experiment. This implies that an additional variability contribution must be present, which is not included in the simulation. A possible additional contributor is variability in targeting moiety density per particle; including a targeting moiety density variability per particle in the simulations (with CVdensity = 15%, dark blue) matches the simulated results to the experimental results. A variability in targeting moiety density may originate from variability in surface chemistry (e.g., causing variable NeutrAvidin densities and thus variable targeting moiety densities) or other differences between particles on subparticle length scales. Such variability on a smaller length scale, i.e., intraparticle variability, will be discussed in the next section.

Intraparticle Targeting Moiety Variability

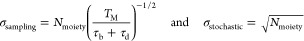

The intraparticle targeting moiety variability was investigated by DNA-PAINT experiments.9 The imaging data were used to confirm or reject whether the positions of these moieties on the particle surface were spatially randomly distributed. Figure 3a shows the positions of (a subset of) targeting moieties obtained in a DNA-PAINT measurement on a single particle (see Supporting Information Section 2.1). Since the targeting moieties are located on the surface of a spherical particle, the 2D localization data need to be projected on a hemisphere (see Supporting Information Section 2.2) to calculate the true distance (great-circle distance) between the localizations. The dashed circle visualizes the projection of the particle on the xy-plane based on the DNA-PAINT localization cloud (see Supporting Information Section 4).

Intraparticle targeting moiety variability studied using DNA-PAINT experiments. (a) Example of an experimentally measured 2D and calculated 3D localization image of DNA-PAINT localizations with the contours of the particle (black dashed line). Using the x- and y-coordinates of the localizations and the calculated diameter of the localization cloud, a 3D localization image on the lower particle hemisphere can be reconstructed. (b) Examples of simulated true positions of targeting moieties (blue) and simulated DNA-PAINT localizations (red) with corresponding zm per particle for three cases: randomly distributed targeting moieties, 25% clustering and 75% random, and 100% clustering of targeting moieties. For an increasing degree of clustering, more negative zm values were found. For this example, a cluster size of 25 nm and an average of 10 ssDNA molecules per cluster were used as an example. (c) Experimentally determined zm (green line) and simulated zm (red line) values as a function of the particle coverage by the complementary ssDNA. Here the particles are incubated with a dilution series of ssDNA comprising 2.9% of complementary ssDNA and the remainder noncomplementary ssDNA equal in length. For all data points, a systematic difference could be observed which indicates the presence of clustered targeting moieties. The experimental data were measured in two fields of view with approximately 102 particles each. The distribution shows zm per particle for a ssDNA coverage of 2.9%, with zm = −1.2 ± 0.6 (mean ± SD). The arrow indicates that a negative zm corresponds to clustered targeting moieties. The errors indicated in the figure are the standard deviations.

Figure 3b quantifies the targeting moiety clustering and the influence of the DNA-PAINT measurement using clustering parameter zm, the standardized mean nearest-neighbor distance, which is a measure for the degree of clustering (negative zm) or dispersion (positive zm) (see Supporting Information Section 5).20 Examples are shown of simulated true targeting moiety positions (blue) on a particle hemisphere (here projected on the xy-plane) and corresponding simulated DNA-PAINT localizations (red). The simulated data are shown for three cases: absence of clustering, superposition of clustered (25% of the localizations) and nonclustered localizations (75% of the localizations), and full clustering (100% of the localizations). For all simulated particles, the zm values are shown for the true positions (blue) and corresponding DNA-PAINT localizations (red). The data show that the zm distributions measured with DNA-PAINT data are wider and that the mean is less negative compared to the true case.

In Figure 3c, experimental zm values calculated from DNA-PAINT results (green line) are shown for all particles in a field of view as a function of particle coverage by ssDNA. The remainder of the ssDNA consists of noncomplementary DNA equal in length. As a reference, DNA-PAINT simulations (red line) are shown for particles without targeting moiety clustering. Both curves show a slight decrease of zm with decreasing coverage. The lower zm values at low coverage represent a clustering artifact due to repeated localizations of the same targeting moiety. This artifact is not present at the higher targeting moiety densities. The experimental results systematically show more negative zm values compared to the simulation over the full particle coverage range, which indicates the presence of clustered true positions of the targeting moieties. The histogram (bottom panel) shows the experimentally found zm per particle at a NeutrAvidin coverage by complementary ssDNA of 2.9%. The distribution is comparable to the simulated distribution for 25% clustering (see Figure 3b) in both mean and width (zm = −1.2 ± 0.6 and zm = −1.4 ± 0.6 respectively), indicating that a degree of nonrandomness is indeed present in the spatial distribution of targeting moieties on the particle surface. A nonrandomness of targeting moiety positions gives an intraparticle contribution to the reactivity variability that scales with the interaction area of the particle (see Supporting Information Section 6). Furthermore, it was found that a comparable distribution of zm values could be observed for the full range of number of targeting moieties per particle (see Supporting Information Section 7). This indicates that the length scale of intraparticle variability is much smaller than the particle size.

The inter- and intraparticle targeting moiety variabilities cause a variability of reactivities of the biofunctionalized particles. This reactivity variability depends in particular on the interaction area of the particle, size of the particle, targeting moiety density, and number of particles. This topic is explored in the next section, using biosensing by particle mobility, a particle-based biosensing method with single-particle and single-molecule resolution.

Reactivity Variability

The reactivity variability was studied using BPM.19 A detailed description of the BPM technique is given in Supporting Information Section 8.1. Briefly, particles are tethered to a surface by a flexible double-stranded DNA stem, causing every particle to move due to thermal motion within a confined space. The sensing capability of the particles results from targeting moieties on the particle and a single targeting moiety on the DNA stem. Target molecules in solution can bind to targeting moieties on the particle as well as to the targeting moiety on the stem; when this happens simultaneously, a compact molecular sandwich arrangement is formed, which strongly reduces the motion of the particle. The molecular interactions are designed to be reversible, causing bound and unbound particle states to be observed over time. The mean unbound state lifetime of a particle decreases when the number of captured target molecules increases. Therefore, the average switching frequency of particles between unbound and bound states increases with the target concentration in solution.

The BPM sensor is designed in such a way that the affinity between target molecule and targeting moieties on the particle is much higher than the affinity between target molecule and moiety on the stem. So the sensing mechanism can be described as a two-step process: target molecules bind first to the targeting moieties on the particle and thereafter to the moiety on the stem. Therefore, the target molecules bound to targeting moieties on the particles function as the reactive component toward the moiety on the stem (see Supporting Information Section 8.1).

Figure 4a shows the response of the sensor as a function of the ssDNA target concentration in solution. The left graph shows the measured particle switching frequency, defined as the mean frequency with which a single particle switches between bound and unbound states. The right graph shows the measured mean state lifetimes. The switching frequency as a function of target concentration follows an S-shaped dose–response curve on a linear–logarithmic scale,19 which is characteristic for a first-order affinity binding process. The mean state lifetime as a function of target concentration shows different behaviors for the mean bound state lifetime τB (red) and mean unbound state lifetime τU (blue). τB is independent of target concentration, because it is determined by the dissociation lifetime of the single-molecular interaction between a ssDNA target molecule and the ssDNA molecule on the stem. In contrast, τU shows a clear concentration dependency, which is in agreement with the fact that the occupation of targeting moieties by target molecules depends on the target concentration in solution.

![Reactivity variability per particle quantified using biosensing

by particle mobility (BPM). (a) Sensing response as a function of

ssDNA target concentration. Left: switching frequency as a function

of target concentration. A Hill equation fit21 (blue dashed line) yields an EC50 value of 170 ±

50 pM. Right: bound and unbound state lifetimes as a function of target

concentration, derived from distributions as shown in panel b.19 The red dashed line represents a constant time;

the blue dashed line represents a fitted line with slope 1/[T]. The

errors indicated in this panel are the standard errors for the switching

frequency and fitting errors for the state lifetimes. (b) State lifetime

analysis for ssDNA target concentrations of 125 pM (blue) and 16 pM

(green). The bound state lifetime shows a single-exponential distribution,

while the unbound state lifetime shows a multiexponential distribution

(red dashed lines). (c) CDFs for two individual particles which show

an approximate single-exponential distribution. (d) Distributions

of the observed state lifetime per particle for both the bound and

unbound states for a target concentration of 125 pM. The width of

the experimentally found distribution (blue) is rather close to the

simulated distribution (red) for the bound state lifetime per particle

(CVexp = 24 ± 3%, and CVsim = 14 ±

1%). However, for the unbound state lifetime per particle, the experimental

and simulated distributions are very different (CVexp =

80 ± 10% and CVsim = 14 ± 2%). The errors indicated

in the caption are the fitting errors.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765820388548-6586ddf1-9357-4d87-83b3-45af67468b29/assets/nn0c08578_0004.jpg)

Reactivity variability per particle quantified using biosensing by particle mobility (BPM). (a) Sensing response as a function of ssDNA target concentration. Left: switching frequency as a function of target concentration. A Hill equation fit21 (blue dashed line) yields an EC50 value of 170 ± 50 pM. Right: bound and unbound state lifetimes as a function of target concentration, derived from distributions as shown in panel b.19 The red dashed line represents a constant time; the blue dashed line represents a fitted line with slope 1/[T]. The errors indicated in this panel are the standard errors for the switching frequency and fitting errors for the state lifetimes. (b) State lifetime analysis for ssDNA target concentrations of 125 pM (blue) and 16 pM (green). The bound state lifetime shows a single-exponential distribution, while the unbound state lifetime shows a multiexponential distribution (red dashed lines). (c) CDFs for two individual particles which show an approximate single-exponential distribution. (d) Distributions of the observed state lifetime per particle for both the bound and unbound states for a target concentration of 125 pM. The width of the experimentally found distribution (blue) is rather close to the simulated distribution (red) for the bound state lifetime per particle (CVexp = 24 ± 3%, and CVsim = 14 ± 1%). However, for the unbound state lifetime per particle, the experimental and simulated distributions are very different (CVexp = 80 ± 10% and CVsim = 14 ± 2%). The errors indicated in the caption are the fitting errors.

The reactivity variability per particle becomes apparent when analyzing the distributions of measured lifetimes. Figure 4b shows the bound and unbound state lifetimes of all observed particles plotted as cumulative distribution functions (CDFs), for a high target concentration (blue) and a low target concentration (green). The CDFs of the bound state lifetimes show straight lines on the used linear–logarithmic scales, equal for both target concentrations. This demonstrates a single-exponential lifetime distribution, which is in agreement with a well-defined single-molecular unbinding process. In contrast, the CDFs of the unbound state lifetimes do not show single-exponential distributions. The data cannot be fitted with straight lines but can be fitted with log-normal distributed mean unbound state lifetimes.19 The fact that the association kinetics do not show a single-exponential distribution suggests the presence of reactivity variability per particle.

Figure 4c plots the CDFs of the unbound state lifetimes for two individual particles as an example; these CDFs of individual particles show single-exponential distributions (red dashed lines) in contrast to the ensemble CDFs in Figure 4b. The CDFs of the two individual particles show a different τU, indicating that the molecular binding process occurs under different local conditions per particle. The experiments show that the observed difference in τU per particle is of static nature, i.e., does not change during a measurement. Therefore, we attribute the observed differences between particles to time-independent heterogeneities, such as differences in the number of accessible targeting moieties. For example, if more targeting moieties are present in the interaction area, then more target molecules are captured at a given target concentration, resulting in a shorter τU (see the two sketches in Figure 4c).

In Figure 4d the experimental (blue) and simulated (red) distributions of both τB and τU per particle are visualized. The simulated distributions were determined using mock data with a measurement duration equal to the experiment; the distribution width reported by the simulations is therefore only caused by the finite measurement time. The observed bound and unbound state lifetimes for all particles were sampled from a single-exponential distribution, with mean bound and mean unbound state lifetimes equal to the peak values of the experimental distributions (blue dashed line). The experimental and simulated distributions for τB (panel d, left) per particle show CVexp = 24 ± 3%, and CVsim = 14 ± 1%, respectively. The slightly larger CVexp compared to CVsim is caused by a relatively long τU for the majority of the particles (see panel d, right), resulting in lower bound state lifetime statistics per particle compared to the simulation. However, the results for unbound state lifetime show large differences between experiment and simulation. The experimental distribution for τU per particle shows a much larger variability than would be expected from the simulated results, namely CVexp = 80 ± 10% in the experiment versus CVsim = 14 ± 2% in the simulation.

The data in Figure 4 show strong differences in the reactivity between individual particles. In the next section, the contribution of each source of variability (stochastic, nonstochastic interparticle, and nonstochastic intraparticle) will be studied. Subsequently, using simulations the reactivity variability will be determined as a function of interaction area, targeting moiety density, particle size, and the number of particles.

Influence of System Parameters on Reactivity Variability

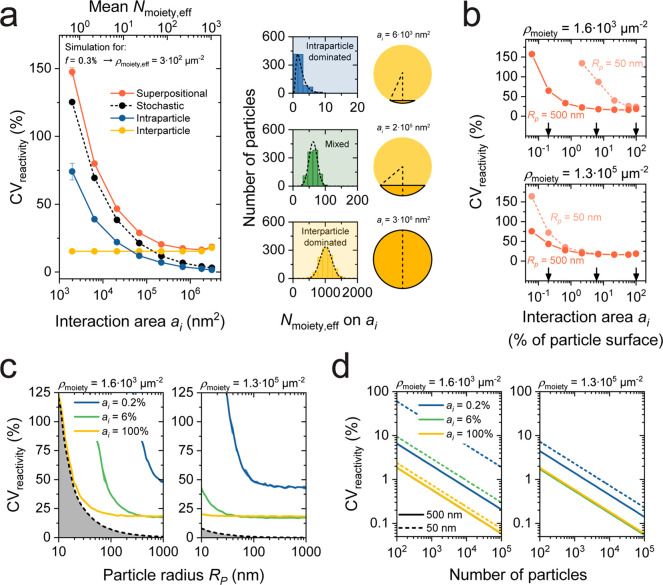

In this section we study by simulations the scaling behavior of different contributors to the reactivity variability for different system parameters, namely, particle size, targeting moiety density, interaction area, and number of particles. In the simulations we generate initial distributions (e.g., of particle size and targeting moiety density) with an experimentally found or estimated mean and width, and subsequently perform calculations on these distributions to determine the number of targeting moieties per interaction area, which determines the reactivity per particle. Finally, we determine the mean and width of the distributions for the given number of particles in the system. The results are shown in Figure 5a for particle-based biosensing by BPM and are generalized in Figures 5b–d for other particle-based biosensing and targeted nanomedicine applications.

Limiting effect of superpositional heterogeneity on the reactivity variability of biofunctionalized particles, studied by simulations. (a) Reactivity variability as a function of the interaction area ai for BPM. Shown are the stochastic (black), interparticle (yellow), and intraparticle (blue) contributions to the reactivity variability as well as the total result (red), for a particle with a radius of 500 nm and a (effective) targeting moiety density ρmoiety,eff of 3 × 102 μm–2. The errors indicated in the figure are standard errors using 5 simulations with 103 particles per simulation; most error bars are smaller than the symbol size. On the right, examples of three distributions of by the effective number of targeting moieties per interaction area ai are visualized. Particles are schematically shown with their corresponding ai indicated in dark orange. The found CVreactivity values are 82 ± 1%, 21.3 ± 0.3%, and 18.9 ± 0.5% (mean ± SEM) for intraparticle heterogeneity dominated, mixed, and interparticle heterogeneity dominated examples, respectively. (b) Reactivity variability per particle as a function of the interaction area for two particle radii (50 and 500 nm) and a low targeting moiety density (top, ρmoiety = 1.6 × 103 μm–2) and high targeting moiety density (bottom, ρmoiety = 1.3 × 105 μm–2). The arrows in the panel indicate three values for ai that are used in panels c and d. (c) Reactivity variability per particle as a function of particle radius for three interaction areas and for a low and high density of targeting moieties. The experimental limit (black dashed line) indicates the limit with only stochastic heterogeneity and an interaction area that equals the full particle surface. The error indicated by the shading is the standard error using 5 simulations with 103 particles per simulation. (d) Ensemble reactivity variability as a function of the number of particles, for particle sizes of 500 nm (solid lines) and 50 nm (dashed lines). Left: the green solid line is behind the yellow solid line. Right: the yellow and green dashed and solid lines are very close to each other.

Figure 5a shows the reactivity variability in BPM as a function of the particle interaction area, highlighting the contributions of stochastic, intraparticle, and interparticle variability. In the BPM design with a single ssDNA molecule on the stem, the reactivity variability per particle is caused by variability in the number of target molecules captured on the particles that can interact with the ssDNA molecule on the stem. Due to the limited length of the tether between particle and substrate, the stem can reach only a limited area on the particle. Only target molecules captured within this interaction area are able to reach the ssDNA molecule on the stem. It was found that the interparticle variability σinterparticle depends on particle size dispersion and targeting moiety density fluctuations (see Figure 2). The intraparticle variability σintraparticle originates from nonuniform functionalization of targeting moieties (see Figure 3) and was found to scale with the inverse square root of ai (see Supporting Information Section 6). The stochastic contribution of the targeting moieties is defined as , with f being the fraction of targeting moieties occupied by a target molecule and Nmoiety the average number of targeting moieties in the interaction area. The fractional occupancy is typically less than 1% in the low-concentration regime of a BPM sensor and depends on the target concentration in solution. For Figure 4d, f was estimated to be approximately 0.3%. The parameters σinterparticle and σreactivity were determined experimentally in the previous sections using qPAINT (Figure 2b) and BPM data (Figure 4d), respectively. On the basis of these parameters, σinterparticle could be estimated and therefore the reactivity variability could be calculated as a function of ai.

The results in Figure 5a show that for a small ai, where the number of targeting moieties Nmoiety is small, the CVreactivity is dominated by stochastic and intraparticle variability. For large ai, where Nmoiety is large, the contribution of interparticle variability dominates. The stochastic contribution scales as CV ∝ ai–1/2, corresponding to Poisson statistics. The intraparticle contribution scales with CV ∝ ai–1/2 as well (see Supporting Information Section 6), while the superposition of all contributions scales roughly with CV ∝ ai–2/3.

The three histograms on the right side of Figure 5a show reactivity distributions for different ai, i.e., distributions of the number of target molecules captured onto a particle interaction area of a given size. This is indicated as Nmoiety,eff, because these target molecules are the moieties effective for generating a signal. The first histogram (at the top) applies to the BPM sensor with a single ssDNA molecule on the stem (see Figure 4), which has a particle interaction area ai of about 6 × 103 nm2. In this condition, the simulations show that the reactivity variability is dominated by stochastic and intraparticle variabilities of targeting moieties that captured a target molecule on the small interaction area of the particle. The simulations predict a CV of 82%, which is similar to the experimental value for the unbound state lifetime reported in Figure 4d. The second histogram applies to a BPM sensor with the whole substrate coated with ssDNA molecules, as reported in previous work.18 This sensor design has a larger particle interaction area of about 6 × 104 nm2 (see Supporting Information Section 8.2). With this larger interaction area, the simulations show that the contributions of stochastic and inter- and intraparticle heterogeneity are approximately equal, giving a CV of 21%. This value is in agreement with the experimentally measured CV for the BPM sensor with the whole substrate coated with ssDNA molecules.18 The third histogram applies to a sensor that would probe the full area of a particle (i.e., ai = 4πRp2). Here, the CV is dominated by interparticle heterogeneity and the CV is about 19%. This result is in agreement with the experimental value found in the qPAINT experiments when the qPAINT induced contribution is neglected (see Figure 2b). Overall, the results show that the stochastic contribution to the reactivity variability in BPM is small with respect to the other sources of variability if the interaction area is at least 5% of the particle surface.

The reactivity variability calculated by simulations in Figure 5a and the corresponding experimental values are in good agreement for different BPM sensor designs, where the particles interact with a biofunctionalized sensing surface. To extrapolate these results toward targeted nanomedicine and particle-based biosensing in general, the calculated reactivity variability is shown in Figures 5b–d for different sizes of interaction area, particle radii, targeting moiety densities, and number of particles.

Figure 5b shows the reactivity variability as a function of interaction area for two particle radii Rp (50 and 500 nm) and two targeting moiety densities ρmoiety. A lower ρmoiety = 1,600 μm–2 corresponds to an average intermolecular distance of 25 nm and resembles a typical density of a particle surface functionalized with antibodies. A higher ρmoiety = 130,000 μm–2 corresponds to an average intermolecular distance of 3 nm and resembles a typical density of a particle surface functionalized with oligonucleotides. The reactivity variability is expressed as a function of the relative interaction area, i.e., the percentage of the total particle surface. Due to stochastics, the reactivity variability is largest for small particles and for a low targeting moiety density. For large interaction areas the reactivity variability converges to about 20%; here the stochastic contribution is small and the variability is dominated by interparticle heterogeneity (see also Figure 5a).

Figure 5c shows how the reactivity variability depends on particle radius, Rp, for two targeting moiety densities, and for three interaction areas (indicated by the arrows in Figure 5b). For all conditions, the reactivity variability decreases as a function of particle radius, due to the decreasing contribution of stochastic and intraparticle variability. The radius where the stochastic and intraparticle contributions become insignificant depends on the interaction area and the targeting moiety density: a smaller interaction area results in a larger reactivity variability while a higher density of targeting moiety results in a smaller reactivity variability.

Figure 5d visualizes the ensemble reactivity variability as a function of the number of particles, shown for two targeting moiety densities, two different particle sizes (solid and dashed lines), and three interaction area percentages (indicated by the three colors). The ensemble reactivity variability is lower (lower CV, better precision) when more particles are used, scaling with the inverse square root of the number of particles. The number of particles required to get a desired CV depends on the particle size, interaction area, and targeting moiety density. The stochastic and intraparticle heterogeneity are large in the case of small particles, low targeting moiety density, and small interaction area. The results show that systems with small particles (<100 nm), low targeting moiety density (for example particles coated with proteins), and a limited interaction area between particle and countersurface, can have very large reactivity variability. When the targeting at the biological site of interest is effectuated by a limited number of particles (<1000 particles), then the number of molecular interactions realized by the particles can vary by tens of percent.

Conclusion

The reactivity variability of biofunctionalized particles used in targeted nanomedicine and particle-based biosensing applications depends on heterogeneities of various kinds. We have studied three factors that contribute to a variability in the number of targeting moieties on the particles, namely, stochastic heterogeneity, interparticle heterogeneity, and intraparticle heterogeneity, jointly referred to as superpositional heterogeneity.

In this work we have presented a comprehensive methodology to quantify particle heterogeneities and their consequences. We have experimentally quantified targeting moiety variabilities using microscopy methods with single-molecule resolution, namely, qPAINT and DNA-PAINT, using DNA-functionalized silica particles as a model system. The data show that the interparticle heterogeneity originates from particle size dispersion and targeting moiety density fluctuations, and intraparticle heterogeneity is caused by nonuniform functionalization.

The three types of heterogeneities cause biofunctionalized particles to have variable reactivities, where reactivity is defined as the number of particle-coupled targeting moieties that are available for interaction toward a countersurface. The variability was quantified by the coefficient of variation (CV), which depends on the interaction area of the particles, the particle size, the targeting moiety density, and the number of particles. The reactivity variability was studied by experiments and simulations for a particle-based biosensing technique with single-particle and single-molecule resolution (biosensing by particle mobility, BPM). The results show that the reactivity variability strongly depends on the size of the interaction area. When the contributions of stochastic and inter- and intraparticle heterogeneity are approximately equal, then the reactivity variability stabilizes and is approximately equal to the reactivity variability for a full-particle interaction.

The results were extrapolated toward the fields of targeted nanomedicine and particle-based biosensing in general, where the precision in the available number of particle-coupled targeting moieties depends on the particle size, targeting moiety density, interaction area, and number of particles. The stochastic and intraparticle heterogeneity are large in the case of small particles, low targeting moiety density, and small interaction area. The results show that large fluctuations (tens of percent) can be expected when targeting effects at a biological site of interest or at a sensor surface are determined by interactions from a limited number of particles.

The methodologies and understanding described in this work warrant further studies on variabilities of biofunctionalized particles on multiple length scales. Studies can include various biofunctionalization strategies, different particle materials, sizes, and geometries of particles, different targeting moiety types, and the influence of complex biological matrices (e.g., protein corona). Measured distributions and heterogeneity simulations can be related to the precision of particle-based targeting effects. The developed insights will enable researchers to engineer particles for biomedical applications with high precision, guided by a thorough understanding of heterogeneities and their collective consequences.

Materials and Methods

qPAINT

All ssDNA oligonucleotides (IDT, HPLC purification) were diluted in Milli-Q water (ThermoFischer Scientific, Pacific AFT 20) to a final concentration of 20 μM for the complementary ssDNA, 10 μM for the ssDNA with a random sequence, and 200 nM for the imager strand. Glass slides (25 × 75 mm, no. 1, Menzel-Gläser) were cleaned by 15 min sonication in methanol (VWR, absolute) and thereafter dried under nitrogen flow. A custom-made fluid cell sticker (Grace Biolabs) with an approximate volume of 24 μL was attached to the glass slide. NeutrAvidin-functionalized silica particles19 were incubated in bulk overnight with biotinylated ssDNA at the required concentration. The particles were thrice centrifugally washed in PBS (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7.4) at 6000g for 5 min using a tabletop spinner (Eppendorf MiniSpin). Finally, the particles were resuspended in PBS to a final concentration of 0.17 mg mL–1 (0.26 pM) and sonicated using an ultrasonic probe (Hielscher). Thereafter, the silica particles were added to the fluid cell and nonspecifically absorbed to the glass surface for 30 min (approximately 100 particles per field of view). After incubation, the fluid cell was washed with 200 μL of buffer B+ (5 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05 vol % Tween-20 at pH 8.0) to remove unbound particles and change the buffer in the fluid cell. Finally, 200 μL of imager strand of the required concentration in buffer B+ was added and the fluid cell was closed using sticky tape. Imaging at a 60× magnification (Nanoimager S, ONI) was performed under TIR conditions using a 647 nm laser at 50 mW at a frame rate of 13.3 Hz for 30 min. Thresholding the integrated pixel intensity of the ROI around each single particle was used to determine binding and unbinding events of imager strands. The mean dark time was extracted by fitting all observed dark times to a single-exponential distribution.

DNA-PAINT

Experimental conditions are described under qPAINT. Drift correction was performed by cross-correlation. After drift correction, the positions of the targeting moieties were determined by clustering the DNA-PAINT localizations both in space and time; DNA-PAINT localizations were clustered into a single targeting moiety position if the distance between DNA-PAINT localizations was less than 100 nm in space and less than 15 frames in time. The diameter of the localization cloud was determined using the area of the convex hull; this diameter represents the diameter of the particle (see Supporting Information Section 4). Second, the localization cloud was centered by averaging all targeting moiety positions after discarding top and bottom 5% outliers. The centered positions are projected on a sphere with the calculated diameter. The nearest-neighbor distance is determined for each position by calculating the great-circle distance to the closest position.

BPM Assay

Glass slides (25 × 75 mm, no. 5, Menzel-Gläser) were cleaned by 15 min of sonication in methanol (VWR, absolute), isopropanol (VWR, absolute), and methanol (VWR, absolute) baths. After each sonication step, the glass coverslips were dried under nitrogen flow. A custom-made fluid cell sticker (Grace Biolabs) with an approximate volume of 60 μL was attached to the glass slide. A flow cell was made by inserting tubing (Freudenberg Medical, monolumen) into the fluid cell sticker and connecting this tubing to a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus, Pump 11 Elite). First the flow cell was prewetted with PBS (130 mM NaCl, 7 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM NaH2PO4 at pH 7.4) at a flow speed of 500 μL min–1 for 2 min. Functionalization of the glass substrate was performed by physisorption of 83 ng mL–1 anti-digoxigenin antibodies (ThermoFischer Scientific) in PBS for 60 min. Finally, the glass substrate was blocked by incubation with 1.0 wt % casein (Sigma-Aldrich, casein sodium salt from bovine milk) in PBS for 60 min. After each incubation step, the fluid cells were flushed with PBS (250 μL min–1 for 1 min). NeutrAvidin-functionalized silica particles19 were incubated in bulk with 10 nM nanoswitch19 for 10 min. Subsequently, the particles were coated with ssDNA by an incubation with 40 μM biotin-labeled single-stranded oligonucleotide. The particles were thrice centrifugally washed in 1.0 wt % BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, lyophilized powder, essentially globulin free, low endotoxin, ≥98%) and 0.05 vol % Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS at 6000g for 5 min using a tabletop spinner (Eppendorf MiniSpin). Finally, the particles were resuspended in PBS/BSA/Tween-20 to a final concentration of 0.17 mg mL–1 (0.26 pM) and sonicated using an ultrasonic probe (Hielscher). The particles were added to the flow cell at a flow speed of 50 μL min–1 for 5 min and incubated for 30 min. After incubation, the fluid cell was turned over and subsequently flushed with PBS/BSA/Tween-20 at a flow speed of 50 μL min–1 for 5 min to remove unbound particles. ssDNA target (IDT, standard desalting) at the required concentration in PBS/BSA/Tween-20 was added at a flow speed of 50 μL min–1 for 5 min and incubated for 20 min. Samples were observed under a white light source using a microscope (Leica DM6000M) using a dark field illumination setup at a total magnification of 20× (Leica objective, N PLAN EPI BD, 20× , NA 0.4). A field of view of approximately 400 × 400 μm2 was imaged using a CMOS camera (Grasshopper 2.3 MP Mono USB3 Vision, Sony Pregius IMX174 CMOS sensor) with an integration time of 10 ms and a sampling frequency of 30 Hz. The silica particles were tracked using the center-of-intensity of the bright particles on the dark background. Trajectory parameters were calculated which describe the motion pattern and were used to select single-tethered particles.17 The state lifetimes were extracted using a previously described method.19

Simulations of BPM Assay

Data were simulated using experimental positional data of bound and unbound particles. For each simulation, two single-exponential distributions were generated: one with a given mean bound state lifetime and one with a given mean unbound state lifetime. The particle traces were reconstructed block-by-block with each block length according to the two predefined single-exponential distributions. Nonspecific interactions and inter- and intraparticle heterogeneity were neglected. Subsequent time-dependent analysis was performed as if experimental data were analyzed.

Simulations on Reactivity Variability

Two independent (normal) distributions were generated for the particle diameter (CVsize = 5%) and targeting moiety density (CVdensity = 15%); both a particle size and a targeting moiety density were assigned randomly to a particle. The spherical cap area (i.e., the interaction area) was calculated for each particle. Using the assigned particle size and targeting moiety density, the (mean) number of targeting moieties on the spherical cap area was calculated. In the absence of intraparticle heterogeneity, the number of targeting moieties per spherical cap and the number of target molecules per spherical cap are Poisson distributed. To include intraparticle heterogeneity, a log-normal distributed number of targeting moieties per spherical cap was used as well. The variance of the log-normal distribution of the number of targeting moieties on the interaction area σintraparticle2 was matched to the experimental value of the reactivity variability found in Figure 4d and Supporting Information Section 6. Subsequently, the number of targeting moieties per spherical cap was fitted by a log-normal distribution, from which the CVreactivity was calculated.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsnano.0c08578.

Details on measurement techniques qPAINT, DNA-PAINT, and BPM, inter- and intraparticle heterogeneity, and correlation between inter- and intraparticle variabilities (PDF)

Author Contributions

All authors conceived and designed the methodology, measurement system, and experiments. R.M.L. performed the experiments, simulations, and data analysis. All authors interpreted the data, discussed results, and co-wrote the manuscript. All authors approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

All data supporting the findings, data analysis, and simulation codes of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matěj Horáček for his help with qPAINT analysis.

How

Reactivity Variability of Biofunctionalized Particles

Is Determined by Superpositional Heterogeneities

How

Reactivity Variability of Biofunctionalized Particles

Is Determined by Superpositional Heterogeneities